Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2770

Peer-review started: July 18, 2014

First decision: September 15, 2014

Revised: October 16, 2014

Accepted: November 7, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 234 Days and 10 Hours

AIM: To compare the sensitivity and specificity of CDX2 and alcian blue (AB) pH 2.5 staining in identifying esophageal intestinal metaplasia.

METHODS: One hundred and ninty-nine biopsies from 186 patients were retrospectively reviewed and categorized as Barrett’s esophagus (BE) (n = 108); non-Barrett’s esophagus (NBE) (n = 48); columnar blue cells (CB) and esophageal glands (EG) (n = 43). The biopsies were stained with AB and immunostained for CDX2 using a mouse monoclonal antibody from Biogenex (clone CDX2-88) and the Ventana Discovery X automated immunostainer. The positive and negative predictive value of each group was used to determine the predictive power of CDX2 and AB in diagnosing intestinal metaplasia.

RESULTS: All of the 108 BE biopsies (100%) were positive for AB and 102 of them (94.4%) were positive for CDX2. The six BE patients (5.6%) who failed to stain with CDX2 were found to have lost the focus of intestinal metaplasia upon deeper sectioning for immunostaining. Both AB and CDX2 were negative in 43 out of 48 (89.6%) NBE cases. Five NBE patients (10.4%) were falsely positive for AB due to the presence of EG and CB in these biopsies. These cases were all CDX2 negative. In addition, 5 AB negative NBE were found to be CDX2 positive. Based on these results the CDX2 immunostain had similar sensitivity but higher specificity (100% vs about 91%) than AB in detecting intestinal type metaplasia in these samples. Our data shows that CDX2 has a better PPV in detecting intestinal metaplasia as compared to AB (95.6% vs 71.5%, respectively).

CONCLUSION: CDX2 has a better positive predictive value than AB in detecting intestinal metaplasia. CDX2 may be useful when challenged by gastro-esophageal biopsies containing mimikers of BE.

Core tip: Our data show that the use of CDX2 immunostain in biopsies performed to rule out esophageal intestinal metaplasia (Barrett esophagus) has the advantage of discriminating between Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal glands. The latter is typically strongly positive for alcian blue (AB) pH 2.5 but negative for CDX2. CDX2 also discriminates between BE and columnar blue cells which are also positive for AB. Our data shows that CDX2 has a better positive predictive value in detecting intestinal metaplasia as compared to AB (95.6% vs 71.5% respectively). These results support the utility of CDX2 stain in the correct diagnosis of Barrett esophagus.

- Citation: Johnson DR, Abdelbaqui M, Tahmasbi M, Mayer Z, Lee HW, Malafa MP, Coppola D. CDX2 protein expression compared to alcian blue staining in the evaluation of esophageal intestinal metaplasia. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2770-2776

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2770.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2770

In 2014 there were an estimated 18170 cases of esophageal cancer in the United States and 15450 deaths, highlighting the importance of cancer prevention and of early detection of precursor lesions[1]. As such, the timely and accurate evaluation of esophageal biopsies for evidence of premalignant change such as intestinal metaplasia is an integral component of upper gastrointestinal tract cancer surveillance and patient management. When identified Barrett’s metaplastic changes warrant continued surveillance which involves ongoing histopathologic review of new biopsies over time and their comparison to previous biopsies for evidence of progression[2]. Even when the lesion of interest has been accurately biopsied, subsequent histologic examination can be challenging due to the small size of the biopsy as well as technical artifacts which may distort tissue morphology. In addition, the presence of esophageal glands (EG) and of columnar blue cells (CB) are known mimikers of Barrett’s esophagus (BE) which stain strongly positive for AB and be the source of false positive BE.

Therefore, reliable, highly sensitive and specific tissue biomarkers of premalignant change can be crucial for diagnostic decision making, thereby maximizing the potential for early therapeutic intervention and positively impacting clinical outcomes. The specificity of CDX2 Immunohistochemistry in the setting of intestinal metaplasia is well known[3]. As such CDX2 should offer significant advantages over conventional AB staining in the diagnostic work-up of esophageal biopsies.

CDX2 is a homeobox transcription factor and member of the caudal-related family of CDX homeobox genes whose expression in mouse intestine was originally identified and characterized by James et al[4] and Beck et al[5] some 20 years ago. Throughout the gastrointestinal tract, it is expressed in the epithelium distal to the stomach during both embryological development as well as during adult life playing a role in stem cell differentiation[4,6,7].

In the esophagus CDX2 is expressed in the setting of columnar intestinal metaplasia consistent with its role in development and a finding that can be exploited diagnostically. Indeed, esophageal CDX2 expression has been associated with columnar metaplasia both with and without intestinal metaplasia, and it has been speculated that its expression can even precede metaplastic change[8]. Further in the progression to adenocarcinoma CDX2 has also been shown to undergo down regulation, similar to that of a “tumors suppressor gene”, supporting its mechanistic role in carcinogenesis and its diagnostic role in the identification of metaplastic precancerous epithelium. As such CDX2 is not merely a surrogate of esophageal adenocarcinoma risk but a direct tissue biomarker capable of identifying the precursor lesion of Barrett’s esophageal adenocarcinoma[9].

In this study, we tested the value of CDX2 immuno stain in distinguishing true intestinal metaplasia when challenged by the presence of false alcian blue (AB) positive CB and EG in small biopsies.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Moffitt Cancer Center.

We retrospectively studied all patients, between the ages of 18-85 years, who underwent upper endoscopy to rule out Barrett’s at the Florida Digestive Health Specialists and at the Moffitt Cancer Center over a 12 mo period. 199 biopsies from 186 patients were studied. The patients had a median age of 61.7 years (ranged from 34 to 85), 117 were male and 69 were female.

In this study BE was defined as the presence of goblet cells by HE staining which also showed AB reactivity. CB were defined as nongoblet columnar epithelial cells that were also AB positive. EG were identified by HE staining and AB as well. The designation non-Barrett’s esophagus (NBE) refers to those cases that did not show evidence of goblet cells by HE staining and AB staining. All of the specimens were preserved in 10% buffered formalin prior to embedding in paraffin.

The HE stain biopsies slides and the corresponding AB stains, previously done, were reviewed and the cases were categorized as follows: 108 biopsies with histologically evident goblet cells (BE), 48 biopsies without histologic evidence of goblet cells (NBE), 43 biopsies containing EG, and CB. These cases were then stained for CDX2 following manufacturer recommendations.

The tissues were stained for CDX2 using a mouse monoclonal antibody against CDX2 (Clone CDX2-88, Biogenex, Fremont, CA) at a 1:5 dilution (incubation at 31 °C, 32 min), using the Ventana automated immunostainer Discovery XT (Ventana Medical Systems Inc. Tucson, Arizona).

The slides were dewaxed by heating at 55 °C for 30 min and by 3 washes, 5 mineach with xylene. Tissues were rehydrated by a series of 5-min washes in 100%, 95% and 80% ethanol and distilled water. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min. After blocking with universal blocking serum (Ventana Medical Systems Inc., Tucson, Arizona) for 30 min, the samples were incubated with the primary antibody at 4 °C overnight. The samples were then incubated with biotin-labeled secondary antibody and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase for 30 mineach (Ventana Medical Systems). The slides were developed with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride substrate (Ventana Medical Systems Inc.) and counterstained with hematoxylin (Ventana Medical Systems Inc. Tucson, Arizona). The tissue samples were dehydrated and coversliped. Standard cell conditioning (following the Ventana proprietarian recommendations) was used for antigen retrieval. The specificity of the anti-CDX2 antibody was reported by the manufacturer. Negative control was included by using non immune mouse sera and omitting the CDX2 antibody during the primary antibody incubation step.

The CDX2 stained samples were examined by two independent observers (DC and MA), and a consensus score was reached for each sample. The positive reaction of CDX2 was scored as positive if any glandular cell nucleus stained.

The positive and negative predictive value of each group was calculated. The PPV and NPV were used to determine the predictive power of CDX2 vs AB in determining the accurate diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia.

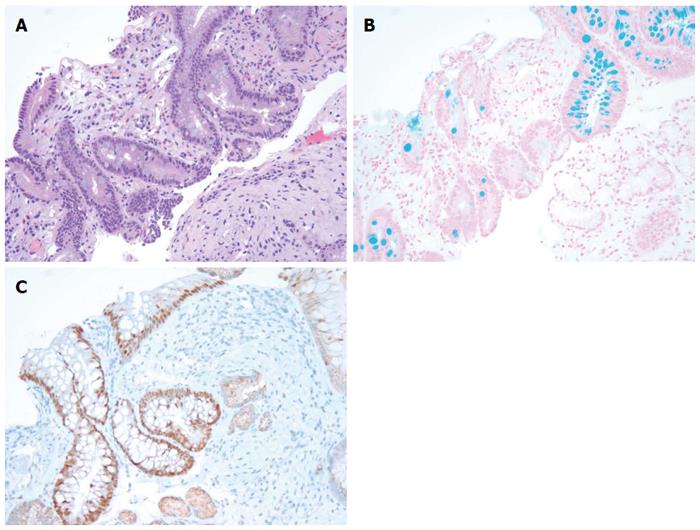

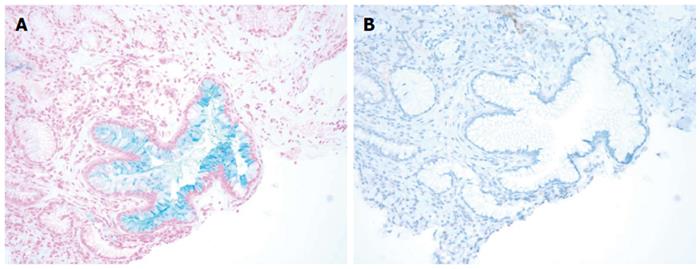

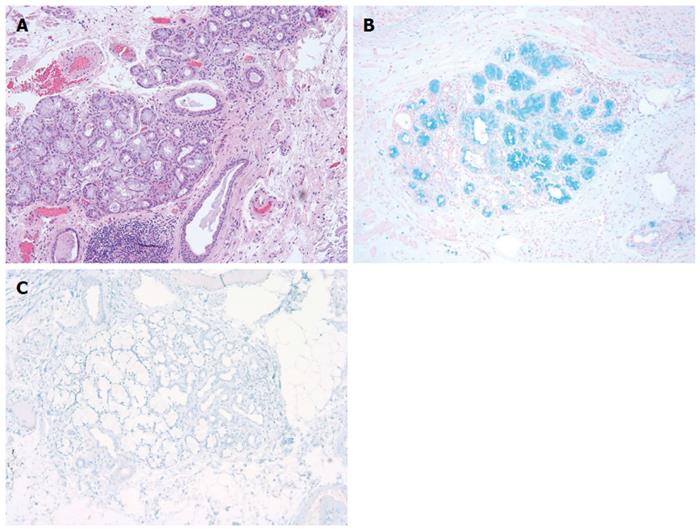

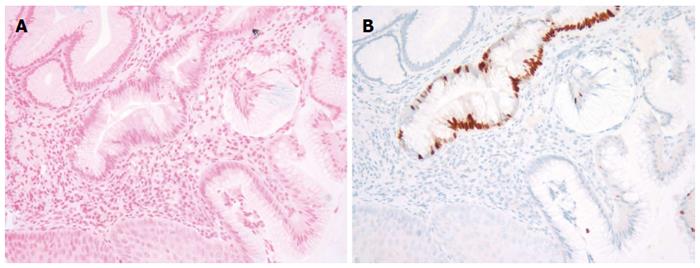

We reviewed a total of 199 esophago-gastric biopsies from 186 patients. The results are summarized in Table 1 below. All of the 108 BE biopsies (100%) were positive for AB and 102 of them (94.4%) were positive for CDX2 (Figure 1). The 6 BE patients (5.6%) who failed to stain with CDX2 were determined, in fact, to have lost the focus of intestinal metaplasia upon deeper sectioning for immunostaining (i.e., false negative CDX2 signal due to tissue loss). Forty-three out of 48 (89.6%) NBE cases were negative for both AB and CDX2. Five NBE patients (10.4%) were falsely positive for AB. This false positive AB stain was attributed to the presence of EG and CB in these biopsies. Each of these five false positives (100%) were consistently negative for CDX2 confirming the absence of BE in these cases (Figures 2 and Figure 3A and 3B). In addition, 5 NBE cases (AB negative) resulted positive for CDX2 (Figure 4).

Our data shows that CDX2 has a better PPV in detecting intestinal metaplasia as compared to AB (95.6% vs 71.5%, respectively).

The results of this study provide further evidence that CDX2 immunostain is a sensitive and specific maker for intestinal metaplasia in the esophagus and that it offers significant advantages, over conventional AB staining, in the detection of BE on esophageal biopsies.

The identification of goblet cells is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of BE which the American College of Gastroenterology defines as “a change in the distal esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized as columnar type mucosa at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy”[10]. One of the roles of the pathologists when dealing with an esophago-gastric biopsy is to identify the intestinal metaplasia. The other is to identify and to grade dysplasia. In questionable cases, or when dealing with small biopsies, it is customary for the pathologists to obtain a special stain for AB that highlights the intracytoplasmic acidic mucin of goblet cells, the marker for intestinal metaplasia. However, the presence of EG and of CB[11-13] are known mimikers of BE and stain strongly positive for AB. Both EG and CB may make the interpretation of small biopsies problematic and be the source of false positive BE.

Several aspects of CDX2 make it a particularly good tissue biomarker in the evaluation of premalignant lesions in the esophagus[14-17]. This marker has been consistently reported in gastric intestinal metaplasia and in intestinal type gastric adenocarcinomas[18-21] while it is not expressed in normal esophageal and gastric epithelial cells[22-24] are CDX2 negative. As a transcription factor, CDX2 shows a nuclear immunostaining pattern. In practice, nuclear expression of transcription factors offers several distinct advantages over cytoplasmic “differentiation” markers. In our experience, transcription factors generally yield an “all or none” signal, with the vast majority of positive cases and the nuclear localization of the signal is much less likely to be confused with biotin or other sources of false-positive cytoplasmic signals.

Prior studies have reported CDX2 expression in BE[25,26]. In this survey, CDX2 was a highly sensitive and specific tissue biomarker for intestinal type metaplasia (BE), equivalent to that of AB staining with regard to sensitivity and superior to AB in terms of specificity (AB alone approximately 91% specific as there were 5 false positive NBE biopsies with AB alone all of which were correctly identified with CDX2 when the biopsy evaluations were performed controlling for: (1) the integrity of the tissue when deeper sections are cut for immunostaining to ensure that focal intestinal metaplasia seen on HE STAINING is not lost in the recuts; and (2) the recognition EG and or CB in the biopsies.

Overall, the positive predictive value in detecting intestinal metaplasia for CDX2 was 95.6% and for AB it was 71.5%. Thus, the adjunct of CDX2 immunostaining can significantly assist in the correct evaluation of esophago-gastric biopsies performed to rule out intestinal metaplasia.

Moving forward, the positive CDX2 stain in 5 NBE cases is intriguing and may indicate the early detection of BE by CDX2. This finding as been observed also by others[8] suggesting that CDX2 positivity in esophageal columnar mucosa may be detectable prior to goblet cells. The clinical implications of this finding require further investigation.

In conclusion, our study further supports the use of CDX2 immuno stain as a useful marker in the diagnosis of BE. The stain proves to be particularly useful especially in situations where the pathologist is challenged by small biopsies containing mimikers of BE CB and/or EG.

In 2014 there were an estimated 18170 cases of esophageal cancer in the United States and 15450 deaths, highlighting the importance of cancer prevention and of early detection of precursor lesions. Esophageal cancer surveillance and patient management relies heavily on the accurate evaluation of esophageal biopsies for evidence of premalignant change such as intestinal metaplasia. In the histological examination of esophageal biopsies, it is essential to identify columnar metaplasia particularly intestinal type (Barrett’s esophagus, BE), a known precursor of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, the most common type of esophageal cancer.

This task can be challenging on small biopsies. When columnar metaplasia has an intestinal phenotype as evidenced by the presence of goblet cells, the alcian blue (AB) pH 2.5 staining can be helpful. However, AB lacks specificity as non-metaplastic, mucin containing esophageal glands (EG) and non-goblet columnar cells (columnar blue cells, CB) also stain positive. Another marker that correlates with intestinal metaplasia in the esophagus is CDX2, a transcription factor normally found in the intestine but which is also expressed in the esophagus undergoing intestinal metaplasia. It has been suggested that CDX2 may offer significant advantages over AB staining. With this study we provide further evidence supporting the utility of CDX2 staining in the diagnosis of esophageal intestinal metaplasia as compared to conventional AB staining.

The identification of goblet cells is a prerequisite for the diagnosis of BE which the American College of Gastroenterology defines as “a change in the distal esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized as columnar type mucosa at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy”. One of the roles of the pathologists when dealing with an esophago-gastric biopsy is to identify the intestinal metaplasia. The other is to identify and to grade dysplasia. In questionable cases or when dealing with small biopsies, it is customary for the pathologists to obtain a special stain for AB that highlights the intracytoplasmic acidic mucin of goblet cells, the marker for intestinal metaplasia. However, the presence of EG and of CB are known mimikers of BE which stain strongly positive for AB. They may make the interpretation of small biopsies problematic and be the source of false positive BE.

Our data shows that CDX2 has a better positive predictive value than AB in detecting intestinal metaplasia (95.6% vs 71.5%, respectively). CDX2 may be useful when challenged by small gastro-esophageal biopsies containing mimikers of BE.

BE is a metaplastic process induced by gastric acid peptic content, eroding the esophageal squamous mucosa and it is characterized by the presence of goblet cells. AB is a special stain highlighting the acidic (intestinal type) mucin contained in BE. CDX2 is a homeobox transcription factor and member of the caudal-related family of CDX homeobox genes and it is expressed in the epithelium distal to the stomach during both embryological development as well as during adult life. In the esophagus CDX2 is expressed in the setting of columnar intestinal metaplasia.

This is a good retrospective study in which the authors analyzed the sensitivity and specificity of CDX2 immunostain in the diagnosis of BE, as compared to conventional AB stain. The reults are interesting and show that CDX2 is more specific than AB in identifying BE, avoiding false positive diagnoses of BE. This is important as it affects patient care.

P- Reviewer: Langner C S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Siegel R, Desantis C, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:104-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1848] [Cited by in RCA: 2073] [Article Influence: 188.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Khor TS, Alfaro EE, Ooi EM, Li Y, Srivastava A, Fujita H, Park Y, Kumarasinghe MP, Lauwers GY. Divergent expression of MUC5AC, MUC6, MUC2, CD10, and CDX-2 in dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinomas with intestinal and foveolar morphology: is this evidence of distinct gastric and intestinal pathways to carcinogenesis in Barrett Esophagus? Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:331-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | James R, Kazenwadel J. Homeobox gene expression in the intestinal epithelium of adult mice. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3246-3251. [PubMed] |

| 4. | James R, Erler T, Kazenwadel J. Structure of the murine homeobox gene cdx-2. Expression in embryonic and adult intestinal epithelium. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:15229-15237. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Beck F, Erler T, Russell A, James R. Expression of Cdx-2 in the mouse embryo and placenta: possible role in patterning of the extra-embryonic membranes. Dev Dyn. 1995;204:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 309] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Stringer EJ, Duluc I, Saandi T, Davidson I, Bialecka M, Sato T, Barker N, Clevers H, Pritchard CA, Winton DJ. Cdx2 determines the fate of postnatal intestinal endoderm. Development. 2012;139:465-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Groisman GM, Amar M, Meir A. Expression of the intestinal marker Cdx2 in the columnar-lined esophagus with and without intestinal (Barrett’s) metaplasia. Mod Pathol. 2004;17:1282-1288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Hayes S, Ahmed S, Clark P. Immunohistochemical assessment for Cdx2 expression in the Barrett metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:110-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Playford RJ. New British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2006;55:442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang KK, Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:788-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 850] [Cited by in RCA: 786] [Article Influence: 46.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Long JD, Orlando RC. Esophageal submucosal glands: structure and function. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2818-2824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hahn HP, Blount PL, Ayub K, Das KM, Souza R, Spechler S, Odze RD. Intestinal differentiation in metaplastic, nongoblet columnar epithelium in the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1006-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Offner FA, Lewin KJ, Weinstein WM. Metaplastic columnar cells in Barrett’s esophagus: a common and neglected cell type. Hum Pathol. 1996;27:885-889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Freund JN, Domon-Dell C, Kedinger M, Duluc I. The Cdx-1 and Cdx-2 homeobox genes in the intestine. Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;76:957-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Silberg DG, Swain GP, Suh ER, Traber PG. Cdx1 and cdx2 expression during intestinal development. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:961-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 464] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Suh E, Chen L, Taylor J, Traber PG. A homeodomain protein related to caudal regulates intestine-specific gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7340-7351. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Suh E, Traber PG. An intestine-specific homeobox gene regulates proliferation and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:619-625. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Almeida R, Silva E, Santos-Silva F, Silberg DG, Wang J, De Bolós C, David L. Expression of intestine-specific transcription factors, CDX1 and CDX2, in intestinal metaplasia and gastric carcinomas. J Pathol. 2003;199:36-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bai YQ, Yamamoto H, Akiyama Y, Tanaka H, Takizawa T, Koike M, Kenji Yagi O, Saitoh K, Takeshita K, Iwai T. Ectopic expression of homeodomain protein CDX2 in intestinal metaplasia and carcinomas of the stomach. Cancer Lett. 2002;176:47-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Seno H, Oshima M, Taniguchi MA, Usami K, Ishikawa TO, Chiba T, Taketo MM. CDX2 expression in the stomach with intestinal metaplasia and intestinal-type cancer: Prognostic implications. Int J Oncol. 2002;21:769-774. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mizoshita T, Inada K, Tsukamoto T, Nozaki K, Joh T, Itoh M, Yamamura Y, Ushijima T, Nakamura S, Tatematsu M. Expression of the intestine-specific transcription factors, Cdx1 and Cdx2, correlates shift to an intestinal phenotype in gastric cancer cells. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:29-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Barbareschi M, Murer B, Colby TV, Chilosi M, Macri E, Loda M, Doglioni C. CDX-2 homeobox gene expression is a reliable marker of colorectal adenocarcinoma metastases to the lungs. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:141-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Werling RW, Yaziji H, Bacchi CE, Gown AM. CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:303-310. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Eda A, Osawa H, Satoh K, Yanaka I, Kihira K, Ishino Y, Mutoh H, Sugano K. Aberrant expression of CDX2 in Barrett’s epithelium and inflammatory esophageal mucosa. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:14-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moskaluk CA, Zhang H, Powell SM, Cerilli LA, Hampton GM, Frierson HF. Cdx2 protein expression in normal and malignant human tissues: an immunohistochemical survey using tissue microarrays. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:913-919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 217] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Phillips RW, Frierson HF, Moskaluk CA. Cdx2 as a marker of epithelial intestinal differentiation in the esophagus. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1442-1447. [PubMed] |