Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2746

Peer-review started: July 26, 2014

First decision: August 15, 2014

Revised: September 8, 2014

Accepted: December 5, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 226 Days and 5 Hours

AIM: To assess the efficacy of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) in lamivudine (LAM)-resistant patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus adefovir (ADV).

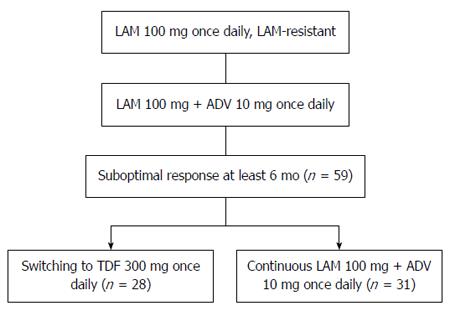

METHODS: We retrospectively analyzed the efficacy of switching to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in suboptimal responders to lamivudine plus adefovir. Charts were reviewed for LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients who visited the Zhejiang Province People’s Hospital and The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, from June 2009 to May 2013. Patients whose serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA remained detectable despite at least 6 mo of LAM plus ADV combination therapy were included. Patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV were randomized to switch to TDF monotherapy (300 mg/d orally; TDF group) or to continuation with LAM (100 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally; LAM plus ADV group) and were followed for 48 wk. Serum HBV DNA was determined at baseline and weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48. HBV serological markers and biochemistry were assessed at baseline and weeks 12, 24, and 48. Resistance surveillance and side effects were monitored during therapy.

RESULTS: Fifty-nine patient were randomized to switch to TDF (n = 28) or continuation with LAM plus ADV (n = 31). No significant differences were found between the groups at baseline. Prior to TDF therapy, all patients had been exposed to LAM plus ADV for a median of 11 mo (range: 6-24 mo). No difference was seen in baseline serum HBV DNA between the two groups [5.13 ± 1.08 log10 copies/mL (TDF) vs 5.04 ± 31.16 log10 copies/mL (LAM + ADV), P = 0.639]. There was no significant difference in the rates of achieving complete virological response (CVR) at week 4 between the TDF and LAM + ADV groups (17.86% vs 6.45%, P = 0.24). The rate of achieving CVR in the TDF and LAM plus ADV groups was 75% vs 16.13% at week 12, 82.14% vs 22.58% at week 24, 89.29% vs 25.81% at week 36, and 96.43% vs 29.03% at week 48, respectively (P < 0.001). The rate of alanine aminotransferase normalization was significantly higher in the TDF than in the LAM plus ADV group at week 12 (75% vs 17.86%, P < 0.001), but not at week 24 (78.57% vs 54.84%, P = 0.097) or 48 (89.26% vs 67.74%, P = 0.062). Patients were hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positive at baseline. There was no significant difference in HBeAg negativity between the TDF and LAM plus ADV groups at week 48 (4% vs 0%, P = 0.481). There were no drug-related adverse effects at week 48 in either group.

CONCLUSION: Switching to TDF monotherapy was superior to continuous add-on therapy in patients with LAM-resistant CHB with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV.

Core tip: We retrospectively assessed the efficacy of switching to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) monotherapy and continuous lamivudine (LAM) plus adefovir (ADV) combination therapy in LAM-resistant chronic hepatitis B (CHB) patients with suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV. Switching to TDF was effective and safe for LAM-resistant CHB patients and exerted stronger antiviral activity than continuous add-on therapy at week 48. Our findings suggest that suboptimal responders to LAM plus ADV should be switched as soon as possible to antiviral agents with higher potency, and TDF would be a viable option.

- Citation: Yang DH, Xie YJ, Zhao NF, Pan HY, Li MW, Huang HJ. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate is superior to lamivudine plus adefovir in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2746-2753

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2746.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2746

Nucleoside/nucleotide analogs (NAs), which inhibit reverse transcription by hepatitis B virus (HBV) polymerase, are an important class of drugs that changed the treatment paradigm and prognosis of chronic hepatitis B (CHB).

Oral NA therapy has advantage over interferon therapy because of its potent antiviral effects, good tolerance, lower side-effect profile, and convenience[1]. Previous studies have shown that lamivudine (LAM) is effective in patients with cirrhosis and CHB. However, the clinical benefit of LAM has a low genetic barrier to resistance. Resistance to LAM was attributed to substitution of methionine in the tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspartate (YMDD) motif in the HBV polymerase by valine or isoleucine, known as the rtM204V/I mutations[2,3]. LAM resistance was observed in 15%-30% of patients after 1 year of LAM treatment and reached 70% after 5 years[4]. Drug-resistant HBV mutants lead to treatment failure and progression to liver disease[5]. Many CHB patients commenced antiviral treatment with LAM in China, which resulted in virological breakthrough and development of genotypic resistance during treatment. Adefovir dipivoxil (ADV), which was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration in 2002, is effective for both wild-type and YMDD-mutant HBV and has been a standard rescue treatment for patients with LAM-resistant HBV infection[6,7]. Unfortunately, a substantial proportion of patients treated with the LAM-plus-ADV combination show a suboptimal virological response[5], especially when therapy is started at a time of high viral load, or after the emergence of mutations causing resistance to both ADV and LAM[8,9]. ADV-resistant HBV strains have been reported after switching to or adding ADV in patients with LAM resistance[10,11].

Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF), which has been approved in the United States and Europe for the treatment of CHB since 2009[12], is an oral NA with the most potent activity against HBV and a high genetic barrier to resistance. It is also recommended for patients who have developed resistance to lamivudine, entecavir, or telbivudine[13,14]. In patients with LAM-resistant CHB, treatment with TDF was well tolerated without significant adverse events such as renal toxicity and showed an excellent antiviral activity[15]. TDF alone or combined with LAM exerted greater viral reduction than ADV[16,17] for LAM-resistant HBV infection without developing phenotypic resistance[18,19]. Owing to its potent antiviral activity and high genetic barrier to the development of resistance for up to 6 years[20-22], TDF is recommended as first-line therapy for HBV-infected patients in recently published guidelines[12,13,23].

However, experience with TDF in Asian countries, including China, is limited because this drug has not yet been approved for the treatment of CHB in that region. Many CHB patients in China have undergone sequential treatment with LAM, ADV, and/or LAM plus ADV combination to manage antiviral resistance of HBV. Treatment of these patients has begun to emerge as an important and difficult issue for clinicians. The efficacy of TDF treatment in patients with LAM-resistant CHB who show a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV is not well known. In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of switching to TDF monotherapy relative to those continuing LAM plus ADV combination therapy in patients with LAM-resistant HBV and a suboptimal response to ongoing treatment with LAM plus ADV.

Patients eligible for this study were men and women, aged 18-65 years, positive for serum hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) for at least 6 mo. Inclusion criteria were confirmed resistance to LAM and serum HBV DNA level > 1000 copies/mL after combination treatment with LAM (100 mg/d) plus ADV (10 mg/d) for at least 6 mo that was ongoing at the time of randomization. Patients were excluded if they were co-infected with hepatitis A virus, hepatitis C virus, hepatitis D virus, hepatitis E virus, or human immunodeficiency virus; had causes of liver disease other than HBV; had intravenous drug abuse, pregnancy, malignancy, chronic renal failure; or other serious medical illness that might interfere with this trial. Patients were also excluded if they had received prior treatment with an antiviral agent other than LAM and/or ADV.

Charts were retrospectively reviewed for patients with CHB and LAM resistance who visited the Zhejiang Province People’s Hospital and The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University, from June 2009 to May 2013. Patients were randomized to switch to TDF (300 mg/d orally; TDF group) or continuation with LAM (100 mg/d orally) plus ADV (10 mg/d orally; LAM plus ADV group). All patients were followed with clinical examinations and routine laboratory tests and were evaluated at baseline and at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48. HBV DNA levels, serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and HBV markers were quantified. All samples were analyzed for HBV resistance mutations (Figure 1). At each visit, patients were evaluated for compliance with study medication and adverse events. Serum ALT (upper limit of normal: 40 U/L), creatinine, and phosphorus levels were tested by routine automated techniques using an Olympus AU5400 automated analyzer (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and hepatitis B e antibody (anti-HBe) were assessed at baseline and at week 48, by chemiluminescence immunoassay (Abbott ARCHITECT i2000 SR analyzer; Abbott Diagnostics, Chicago, IL, United States).

Written informed consent was given to participate by all of the patients. The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki for clinical studies.

Serum HBV DNA load was assessed by real-time fluorescent quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using a Lightcycler PCR system (FQD-33A; Bioer) in strict accordance with the instructions provided in the reagent kit (Shenzheng PG Biotech Co. Ltd.). The detection limit was approximately 1000 viral genome copies/mL. Measurements of serum HBV DNA levels were made at weeks 0, 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48 during treatment. Complete virological response (CVR) was defined as serum HBV DNA level ≤ 103 copies/mL.

Genotypic resistance to LAM and ADV was determined at baseline by direct sequencing of the PCR amplification products[24]. To detect the mutations, the upstream primer 5’-CTCCAATCACTCACCAACAC-3’ and the downstream primer 5’-GGGTTTAAATGTATACCCA-3’ were used for PCR amplification, and the primer 5’-GTAATTCCCATCCC-3’ was used for sequencing. All primers were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Company (Shanghai, China). PCR amplifications were performed in a PTC-200 Peltier thermal cycler (MJ Research, Watertown, MA, United States) with an initial denaturation of 5 min at 94 °C, followed by 35 amplification cycles of 94 °C for 45 s, 55 °C for 45 s, and 72 °C for 1 min, with a final extension of 5 min at 72 °C. PCR products were purified by using QIAquick PCR Purification Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States). Sequence analysis of the PCR products was performed with DYEnamic ET Dye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Kit (Amersham Bioscience, United States) in a MegaBACE 500 DNA analysis system (Amersham Biosciences Corporation) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequence analysis software was used to analyze the results.

Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 13.0 (Chicago, IL, United States). All data are expressed as mean ± SD with a range for continuous variables, and a number with percentage for categorical variables unless otherwise indicated. The cumulative probabilities of virological and biochemical responses were evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The log-rank test was used to evaluate differences between the two groups. Between-group comparisons of continuous variables were determined using independent t tests, and categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

We included 59 patients who had been treated with LAM plus ADV and developed resistance to LAM. Of these patients, 28 (47.45%) were switched to TDF (300 mg) monotherapy, and 31 (52.55%) continued to receive combination therapy with LAM (100 mg) plus ADV (10 mg; Table 1). The baseline demographic and disease characteristics of the two treatment groups were well balanced (Table 1). The average age was 36.36 ± 10.14 years (range: 18-58 years), and 91.52% of the patients were male. Fifty-two patients were HBeAg positive (88.14%) with a mean baseline serum HBV DNA level of 5.08 ± 1.11 log10 copies/mL. All patients were exposed to LAM plus ADV combination treatment for a median of 11 mo (range: 6-24 mo). Additionally, the rate of HBeAg positivity, the pattern of YMDD mutation, ADV-resistant strain, age, and duration of prior LAM plus ADV treatment were also comparable between the two study groups. The two treatment groups were well balanced for baseline characteristics. In LAM plus ADV treated patients, ADV was used as an add-on therapy in an attempt to suppress LAM-resistant strains; however, the patients developed viral breakthrough with or without genotypic resistance to ADV, or showed a suboptimal virological response.

| Variable | Total (n = 59) | TDF (n = 28) | LAM + ADV (n = 31) | P value |

| Age1 (yr) | 36.36 ± 10.14 (18-58) | 35.81 ± 9.85 (18-56) | 32.06 ± 8.36 (21-58) | 0.656 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 54 (91.52) | 26 (92.9) | 28 (90.32) | 0.698 |

| Initial ALT1 (U/L) | 101.54 ± 26.14 | 98.25 ± 28.16 | 104.94 ± 24.33 | 0.542 |

| Serum creatinine1 (μmol/L) | 94.61 ± 18.92 | 89.85 ± 18.83 | 98.82 ± 16.65 | 0.340 |

| Serum phosphorus1 (mmol/L) | 1.14 ± 0.23 | 1.14 ± 0.22 | 1.16 ± 0.25 | 0.740 |

| HBeAg positivity, n (%) | 52 (88.14) | 25 (89.29) | 27 (87.10) | 1.000 |

| Cirrhosis, n (%) | 5 (8.49) | 2 (7.14) | 3 (9.68) | 0.932 |

| Serum HBV DNA1 (log10 copyies/mL) | 5.08 ± 1.11 | 5.13 ± 1.08 | 5.04 ± 31.16 | 0.639 |

| Prior LAM + ADV therapy (mo) | ||||

| Median | 11 | 11 | 12 | |

| Range (mix-max) | 6-24 | 6-22 | 8-24 | |

| LAM resistance mutation, n (%) | 47 (79.66) | 23 (82.14) | 24 (77.42) | 0.653 |

| rtM204I/V | 15 (25.42) | 6 | 9 | |

| rtL180M | 4 (6.78) | 2 | 2 | |

| rtM204I/V + rtL180M | 28 (47.46) | 15 | 13 | |

| ADV resistance mutation, n (%) | 3 (5.08) | 1 (3.57) | 2 (6.45) | 1.000 |

| rtN236T | 0 | 1 | ||

| rtA181T | 1 | 0 | ||

| rtA181V | 0 | 1 | ||

| Unknown2 | 4 | 5 |

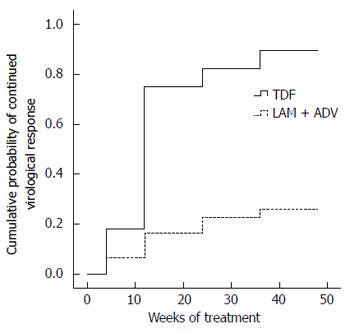

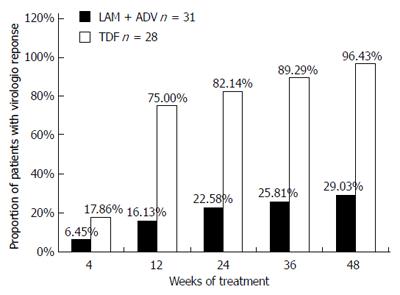

HBV DNA concentrations in the TDF group declined continuously during treatment, whereas viral loads in the LAM plus ADV group remained distributed over a wide range throughout treatment (Figure 2). The number of patients who achieved virological response (serum HBV DNA < 103 copies/mL) gradually increased in the TDF group during treatment, from five (17.86%) at week 4, to 21 (75%) at week 12, 23 (82.14%) at week 24, 25 (89.29%) at week 36, and 27 (96.43%) at week 48 (Figure 2). In contrast, with continued LAM plus ADV combination therapy, only two (6.45%), five (16.13%), seven (22.58%), eight (25.81%), and nine (29.03%) patients showed a virological response at weeks 4, 12, 24, 36, and 48, respectively (Figure 3). The proportion of patients achieving HBV DNA undetectability was significantly greater in the TDF group than in the LAM-plus-ADV group at weeks 12, 24, and 48 (P < 0.001; Table 2). Only one patient with the rtA181V/T mutant strain did not achieve CVR in the TDF group at week 48, but his serum HBV DNA level decreased to 1000 copies/mL with a reduction of 3 log10 copies/mL accomplishing near CVR. One of 25 (4%) patients in the TDF group and none of 27 in the LAM plus ADV group became HBeAg negative at week 48 (P > 0.05), and 1/25 (4%) in the TDF group and none of 27 in the LAM plus ADV group became HBeAg negative at week 48 (P > 0.05)

| Value for patient group | |||

| TDF(n = 28) | LAM + ADV(n = 31) | P value | |

| Normalization of ALT1 | |||

| Week 12 | 21 (75.00) | 5 (17.86) | < 0.001 |

| Week 24 | 22 (78.57) | 17 (54.84) | 0.097 |

| Week 48 | 25 (89.26) | 21 (67.74) | 0.062 |

| HBV DNA undetectability (< 103 copies/mL) | |||

| Week 4 | 5 (17.86) | 2 (6.45) | 0.240 |

| Week 12 | 21 (75.00) | 5 (16.13) | < 0.001 |

| Week 24 | 23 (82.14) | 7 (22.58) | < 0.001 |

| Week 36 | 25 (89.29) | 8 (25.81) | < 0.001 |

| Week 48 | 27 (96.43) | 9 (29.03) | < 0.001 |

| HBeAg loss at week 48 | 1 (4) | 0 | 0.481 |

The proportion of ALT normalization was higher in the TDF monotherapy group than in the LAM plus ADV combination therapy at week 12 (75% vs 17.86%, P < 0.001), but there was no significant difference at week 24 (78.57% vs 54.84%, P = 0.097) or 48 (89.26% vs 67.74%, P = 0.062). Among patients who were HBeAg positive at baseline, 1/25 (4%) in the TDF group and none of 27 in the LAM plus ADV group became HBeAg negative at week 48, and there was no significant difference between the two groups (P = 0.481) (Table 2). No patient achieved HBeAg seroconversion at week 48 in either of the two groups.

Paired baseline and week 48 samples from all study patients with detectable serum HBV DNA were analyzed for HBV resistance mutations. In the LAM plus ADV group, ADV mutations detected at baseline were retained at week 48, and two patients had developed the mutations of rtA181V (1/31) and rtN236T (1/31). No patients retained ADV mutations in the TDF group. Two patients in the TDF group had a CVR at week 12, and their HBV DNA levels rebounded to 1000 copies/mL at week 24 (but no patient had resistance to TDF). The two patients were switched to Truvada (TDF plus emtricitabine) therapy and continued to show a decline in HBV DNA levels and achieved undetectability (< 1000 copies/mL) at week 48. The HBV DNA levels in two HBeAg-positive patients (one was male and one was female) were 109 copies/L at baseline before LAM therapy. The two patients were aged 42 and 56 years and had a family history of hepatitis B. They experienced LAM monotherapy for > 2 years and LAM plus ADV for > 8 mo. The serum HBV DNA titer increased to 7 log10 copies/mL before switching to TDF and LAM resistance mutations were found in two patients.

The nine patients with virological breakthrough during continued LAM treatment had no detection of any known genotypic resistance mutation to LAM (rtM204V/I or rtL180M) or ADV (rtN236T or rtA181T or rtA181V). Four of these patients were switched to TDF monotherapy and achieved a virological response (serum HBV DNA concentration < 1000 copies/mL) at week 48. Five patients continued LAM plus ADV combination therapy and serum HBV DNA was ≥ 1000 copies/mL at week 48.

Adverse effects were similar in both groups. There were no clinically significant adverse events during TDF monotherapy. No patient in the TDF group had early discontinuation or dose reduction. No patient experienced ALT flares, increased creatinine (> 123 μmol/L), or serum phosphorus levels < 1.6 mmol/L during the treatment period. Two patients had serious oral ulcers in the TDF group. All these adverse events were considered as unrelated to the study medication. No patient required termination or interruption of therapy.

This study is the first report that provides a direct comparison of the antiviral efficacy of switching to TDF monotherapy and continuous LAM plus ADV combination therapy in LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV. The results clearly showed that treatment for 48 wk with TDF monotherapy significantly suppressed HBV replication in LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV combination therapy. In contrast, continuation of the combination of LAM plus AVD provided little antiviral benefit. LAM plus ADV combination therapy has been recommended as one of the treatment options for patients with LAM-resistant HBV infection[8,25]. This combination therapy may reduce the development of LAM-resistant mutations. However, because continued LAM treatment has no effect on virological response in patients with LAM-resistant HBV infection, the LAM plus ADV combination does not result in greater antiviral efficacy than that offered by ADV monotherapy[25]. ADV has modest potency in suppressing HBV DNA replication, therefore, a substantial proportion of patients show an inadequate or suboptimal virological response during treatment with LAM plus ADV. Response to LAM plus ADV was especially reduced in patients with high viral loads and mutations causing resistance to both drugs (e.g., rtA 181V/T with or without rtN236T) at the initiation of treatment[26-28].

The efficacy of TDF in the treatment of prior NA-refractory HBV infection has been evaluated[17,18,23]. A TDF-containing treatment regimen suppressed HBV DNA in CHB patients with multiple treatment failures with NA therapy, regardless of genotypic resistance or previous treatment regimens[29-31]. It seemed that TDF would be a promising candidate for LAM-resistant patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV[32]. Our present data show that switching to TDF is highly effective and safe for patients with LAM-resistant CHB and a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV, and exerts stronger anti-HBV activity than continuous add-on therapy. Treatment of 28 patients with subsequent TDF monotherapy resulted in 82.14% CVR at week 24 and 96.43% at week 48. Continuing LAM + ADV offered little antiviral benefit to patients with LAM-resistant HBV infection with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV, and only 29.03% of patients who continued on LAM plus ADV achieved a virological response at week 48. HBV DNA undetectability was significantly greater in the TDF group than in the LAM plus ADV group at weeks 12, 24, 36, and 48 (Table 2; P < 0.01). The cumulative probability of CVR in the TDF group was higher than that in the LAM plus ADV group (Figure 2; P < 0.01). This phenomenon was observed up to 48 weeks. Patterson et al[32] reported a CVR rate of 64% at 96 wk of TDF rescue therapy in CHB patients following failures of both LAM and ADV treatment. The result was thought to be rapid and potent suppressive activity of TDF and insufficient potency of LAM plus ADV combination therapy in LAM-resistant CHB patients. However, in another study, the presence of ADV resistance was considered to decrease the efficacy of TDF. In the current study, one patient with the rtA181V/T mutant strain did not reach CVR, but the effect of ADV resistance on the antiviral efficacy of TDF cannot be concluded from the results of this study because of the small sample size, and this should be explored in further research.

As a result of the high rate of undetectable DNA in the TDF group, we observed a significant difference at week 12, when the rate of ALT normalization was increased rapidly to 75% (21/28) in the TDF group, and > 17.86% (5/31) in the LAM plus ADV groups. The rate of HBeAg loss did not differ at 48 wk between the TDF and LAM plus ADV groups (4% vs 0%, P > 0.05) in patients who were positive for HBeAg. It appears that a greater HBV DNA reduction may not necessarily accelerate HBeAg loss.

TDF was well tolerated during the treatment period, and no renal toxicity was observed after 48 wk of TDF monotherapy. However, many postmarketing observations found that TDF is associated with nephrotoxicity, including increased serum creatinine levels, hypophosphatemia, renal insufficiency or failure, and Fanconi syndrome. Ezinga et al[33] reported that parameters of kidney tubular dysfunction (KTD) were frequently observed in patients receiving long-term, TDF-containing, combination antiretroviral therapy. KTD is associated with higher TDF plasma concentrations. Renal function should be monitored closely during long-term use of TDF.

This study had some limitations. This was a retrospective analysis without placebo control or blinding. Although objective endpoints (virological and biochemical) were used and drug adherence was ascertained, the lack of blinding might have caused the study patients to pay extra attention to their symptoms or caused the investigators to be more likely to report adverse events. The number of subjects included was small (n = 28), and the follow-up period (48 wk) was relatively short. Thus, longer-duration follow-up assessments are in progress. Further studies with larger sample sizes are necessary to remedy these shortcomings and to elucidate the long-term outcomes of TDF treatment. Although the genotype of HBV could be a factor affecting the efficacy of antiviral agents, we did not perform an analysis of the genotype. However, previous studies have documented that most patients with LAM-resistant CHB in China have genotype B/C. Therefore, these results could be applicable to our study patients, and can represent genotype B/C HBV-infected patients[34-36].

In conclusion, our results suggest that LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV should be switched as soon as possible to antiviral agents with higher potency, and TDF monotherapy would be a viable option for this group of patients.

We acknowledge the staff and patients of the Zhejiang Province People’s Hospital and The First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University for participation in this study. We also acknowledge the Institute of Infectious Diseases, First Affiliated Hospital, College of Medicine, Zhejiang University for assistance with resistance surveillance. The authors are grateful to Li Chen (The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang Chinese Medical University) for her help with the figures.

A substantial proportion of patients with lamivudine (LAM)-resistant chronic hepatitis B (CHB) with add-on adefovir (ADV) combination therapy show a suboptimal virological response. This suboptimal response to antiviral therapy provides little antiviral benefit and increases the rate of emergence of additional resistance mutations, and may lead to disease progression. Suboptimal response to nucleoside/nucleotide analogs has also become a new challenge for antiviral therapy of CHB patients. However, there is no standard optimal strategy for these patients.

This study is believed to be the first to provide a direct comparison of the antiviral efficacy of switching to Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) monotherapy and continuous LAM plus ADV combination therapy in patients with LAM-resistant CHB with a suboptimal response to LAM-plus-ADV.

The results show that switching to TDF is highly effective and safe for LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV, and exerts stronger anti-HBV activity than continuous add-on therapy at 48 wk.

The results suggest that LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV should be switched as soon as possible to antiviral agents with higher potency, and TDF monotherapy would be a viable option for this group of patients.

The authors assessed a comparison of the antiviral efficacy of switching to TDF monotherapy and continuous LAM plus ADV combination therapy in LAM-resistant CHB patients with a suboptimal response to LAM plus ADV. This is the first comparison of these two different antiviral therapies. These results may also have implications in the antiviral therapy of CHB patients.

P- Reviewer: Abraham P, Kitrinos KM S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Choi MS, Yoo BC. Management of chronic hepatitis B with nucleoside or nucleotide analogues: a review of current guidelines. Gut Liver. 2010;4:15-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lai CL, Dienstag J, Schiff E, Leung NW, Atkins M, Hunt C, Brown N, Woessner M, Boehme R, Condreay L. Prevalence and clinical correlates of YMDD variants during lamivudine therapy for patients with chronic hepatitis B. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 490] [Cited by in RCA: 493] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kobayashi M, Suzuki F, Akuta N, Yatsuji H, Hosaka T, Sezaki H, Kobayashi M, Kawamura Y, Suzuki Y, Arase Y. Correlation of YMDD mutation and breakthrough hepatitis with hepatitis B virus DNA and serum ALT during lamivudine treatment. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:125-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yao GB, Zhu M, Cui ZY, Wang BE, Yao JL, Zeng MD. A 7-year study of lamivudine therapy for hepatitis B virus e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients in China. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:131-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rapti I, Dimou E, Mitsoula P, Hadziyannis SJ. Adding-on versus switching-to adefovir therapy in lamivudine-resistant HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:307-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Perrillo R, Hann HW, Mutimer D, Willems B, Leung N, Lee WM, Moorat A, Gardner S, Woessner M, Bourne E. Adefovir dipivoxil added to ongoing lamivudine in chronic hepatitis B with YMDD mutant hepatitis B virus. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:81-90. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Peters MG, Hann Hw Hw, Martin P, Heathcote EJ, Buggisch P, Rubin R, Bourliere M, Kowdley K, Trepo C, Gray Df Df. Adefovir dipivoxil alone or in combination with lamivudine in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:91-101. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Keeffe EB, Dieterich DT, Han SH, Jacobson IM, Martin P, Schiff ER, Tobias H. A treatment algorithm for the management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: 2008 update. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1315-1341; quiz 1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 336] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee YS, Suh DJ, Lim YS, Jung SW, Kim KM, Lee HC, Chung YH, Lee YS, Yoo W, Kim SO. Increased risk of adefovir resistance in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B after 48 weeks of adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy. Hepatology. 2006;43:1385-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Santantonio T, Fasano M, Durantel S, Barraud L, Heichen M, Guastadisegni A, Pastore G, Zoulim F. Adefovir dipivoxil resistance patterns in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2009;14:557-565. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Sinn DH, Lee HIe, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Lee JH. Virological response to adefovir monotherapy and the risk of adefovir resistance. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3526-3530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of chronic hepatitis B. J Hepatol. 2009;50:227-242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1152] [Cited by in RCA: 1155] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2171] [Article Influence: 135.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ayoub WS, Keeffe EB. Review article: current antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis B. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1145-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Corsa AC, Liu Y, Flaherty JF, Mitchell B, Fung SK, Gane E, Miller MD, Kitrinos KM. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate through 96 weeks of treatment in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:2106-2112.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Del Poggio P, Zaccanelli M, Oggionni M, Colombo S, Jamoletti C, Puhalo V. Low-dose tenofovir is more potent than adefovir and is effective in controlling HBV viremia in chronic HBeAg-negative hepatitis B. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4096-4099. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Hann HW, Chae HB, Dunn SR. Tenofovir (TDF) has stronger antiviral effect than adefovir (ADV) against lamivudine (LAM)-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV). Hepatol Int. 2008;2:244-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van Bömmel F, Zöllner B, Sarrazin C, Spengler U, Hüppe D, Möller B, Feucht HH, Wiedenmann B, Berg T. Tenofovir for patients with lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and high HBV DNA level during adefovir therapy. Hepatology. 2006;44:318-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fung S, Kwan P, Fabri M, Horban A, Pelemis M, Hann HW, Gurel S, Caruntu FA, Flaherty JF, Massetto B. Randomized comparison of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate vs emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:980-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Heathcote EJ, Marcellin P, Buti M, Gane E, De Man RA, Krastev Z, Germanidis G, Lee SS, Flisiak R, Kaita K. Three-year efficacy and safety of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate treatment for chronic hepatitis B. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:132-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Snow-Lampart A, Chappell B, Curtis M, Zhu Y, Myrick F, Schawalder J, Kitrinos K, Svarovskaia ES, Miller MD, Sorbel J. No resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate detected after up to 144 weeks of therapy in patients monoinfected with chronic hepatitis B virus. Hepatology. 2011;53:763-773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kitrinos KM, Corsa A, Liu Y, Flaherty J, Snow-Lampart A, Marcellin P, Borroto-Esoda K, Miller MD. No detectable resistance to tenofovir disoproxil fumarate after 6 years of therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2014;59:434-442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | European Association For The Study Of The Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: Management of chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Hepatol. 2012;57:167-185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2323] [Cited by in RCA: 2401] [Article Influence: 184.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Li MW, Hou W, Wo JE, Liu KZ. Character of HBV (hepatitis B virus) polymerase gene rtM204V/I and rtL180M mutation in patients with lamivudine resistance. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2005;6:664-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ohishi W, Chayama K. Treatment of chronic hepatitis B with nucleos(t)ide analogues. Hepatol Res. 2012;42:219-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fung SK, Andreone P, Han SH, Rajender Reddy K, Regev A, Keeffe EB, Hussain M, Cursaro C, Richtmyer P, Marrero JA. Adefovir-resistant hepatitis B can be associated with viral rebound and hepatic decompensation. J Hepatol. 2005;43:937-943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee JM, Park JY, Kim do Y, Nguyen T, Hong SP, Kim SO, Chon CY, Han KH, Ahn SH. Long-term adefovir dipivoxil monotherapy for up to 5 years in lamivudine-resistant chronic hepatitis B. Antivir Ther. 2010;15:235-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Monavari SH, Keyvani H, Mollaie H, Roudsari RV. Detection of rtN236T mutation associated with adefovir dipivoxil resistance in Hepatitis B infected patients with YMDD mutations in Tehran. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5:76-80. [PubMed] |

| 29. | van Bömmel F, de Man RA, Wedemeyer H, Deterding K, Petersen J, Buggisch P, Erhardt A, Hüppe D, Stein K, Trojan J. Long-term efficacy of tenofovir monotherapy for hepatitis B virus-monoinfected patients after failure of nucleoside/nucleotide analogues. Hepatology. 2010;51:73-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kim YJ, Sinn DH, Gwak GY, Choi MS, Koh KC, Paik SW, Yoo BC, Lee JH. Tenofovir rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients after multiple treatment failures. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:6996-7002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee CI, Kwon SY, Kim JH, Choe WH, Lee CH, Yoon EL, Yeon JE, Byun KS, Kim YS, Kim JH. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir-based rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients with previous nucleo(s/t)ide treatment failure. Gut Liver. 2014;8:64-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Patterson SJ, George J, Strasser SI, Lee AU, Sievert W, Nicoll AJ, Desmond PV, Roberts SK, Locarnini S, Bowden S. Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate rescue therapy following failure of both lamivudine and adefovir dipivoxil in chronic hepatitis B. Gut. 2011;60:247-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ezinga M, Wetzels JF, Bosch ME, van der Ven AJ, Burger DM. Long-term treatment with tenofovir: prevalence of kidney tubular dysfunction and its association with tenofovir plasma concentration. Antivir Ther. 2014;19:765-771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Rodríguez-Nóvoa S, Gómez-Tato A, Aguilera-Guirao A, Castroagudín J, González-Quintela A, Garcia-Riestra C, Regueiro BJ. Hepatitis B virus genotyping based on cluster analysis of the region involved in lamivudine resistance. J Virol Methods. 2004;115:9-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Li SY, Qin L, Zhang L, Song XB, Zhou Y, Zhou J, Lu XJ, Cao J, Wang LL, Wang J. Molecular epidemical characteristics of Lamivudine resistance mutations of HBV in southern China. Med Sci Monit. 2011;17:PH75-PH80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chen XL, Li M, Zhang XL. HBV genotype B/C and response to lamivudine therapy: a systematic review. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:672614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |