Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2731

Peer-review started: October 10, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 19, 2014

Accepted: December 14, 2014

Article in press: December 16, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 150 Days and 17.2 Hours

AIM: To investigate a new modification of pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD)-a mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy.

METHODS: Two hundred and three patients underwent PD from 2009 to 2014 and were classified into two groups: Group A (98 patients), who received PD with a mesh-like running suturing for the pancreatic remnant, and Braun’s enteroenterostomy; and Group B (105 patients), who received standard PD. Demographic data, intraoperative findings, postoperative morbidity and perioperative mortality between the two groups were compared by univariate and multivariate analysis.

RESULTS: Demographic characteristics between Group A and Group B were comparable. There were no significant differences between the two groups concerning perioperative mortality, and operative blood loss, as well as the incidence of the postoperative morbidity, including reoperation, bile leakage, intra-abdominal fluid collection or infection, and postoperative bleeding. Clinically relevant postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) were identified more frequently in Group B than in Group A. Technique A (PD with a mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy) was independently associated with decreased clinically relevant POPF and DGE, with an odds ratio of 0.266 (95%CI: 0.109-0.654, P = 0.004) for clinically relevant POPF and 0.073 (95%CI: 0.010-0.578, P = 0.013) for clinically relevant DGE.

CONCLUSION: An additional mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy during PD decreases the incidence of postoperative complications and is beneficial for patients.

Core tip: How to reduce postoperative morbidity after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is a pressing problem. A new modification of PD, mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and an additional Braun’s enteroenterostomy, was performed in our center. The procedure significantly reduced the postoperative complications, including pancreatic fistula and clinically relevant delayed gastric emptying. These surgical techniques are safe and effective, and are easily mastered by surgeons, which improves outcomes of PD and offers major economic and social benefits.

- Citation: Meng HB, Zhou B, Wu F, Xu J, Song ZS, Gong J, Khondaker M, Xu B. Continuous suture of the pancreatic stump and Braun enteroenterostomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2731-2738

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2731.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2731

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) remains the typical surgical procedure for pancreatic cancer and periampullary malignancy. Despite improvements in the operative technique, suture materials, and perioperative management, the incidence of postoperative complications after PD remains high[1], even in experienced hands. How to reduce postoperative morbidity is a major and pressing problem.

Postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) and delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after PD are important complications that might affect mortality, morbidity, medical costs, and hospital stay. POPF is associated with the surgical technique of pancreatojejunostomy. To prevent pancreatic leakage from pancreatojejunostomy, many measures have been proposed: duct ligation or duct occlusion, administration of octreotide, main pancreatic duct drainage, or different reconstructions of the pancreatojejunal anastomoses. However, there is some debate surrounding most measures regarding decreasing POPF, and the best way to restore pancreatic digestive continuity remains controversial. The incidence of complications after pancreatojejunal anastomosis remains high. Using the definition and grading system for POPF defined by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF), the incidence of clinically significant POPF was about 20.0%[1,2]. DGE is a paresis (partial paralysis) of the stomach, resulting in a longer time of food remaining in the stomach than normal. DGE is not a fatal complication after PD, but it may significantly prolong the hospitalization and increases costs[3]. Some modified digestive reconstructive procedures have been reported to reduce DGE. Nikfarjam et al[4] found that classic PD combined with antecolic anastomosis and retrogastric vascular omental patch was associated with a significant reduction in incidence of DGE. Many attempts have been made to reduce and prevent DGE, but there is lack of convincing evidence for improved outcomes with any of these efforts. A high incidence of DGE still exists, up to 38%-57%[5,6]. Therefore, much work still needs to be done to reduce postoperative complications after PD.

One of most important determinants of POPF is how to manage the pancreatic remnant. Soft pancreatic remnants are vulnerable to development of pancreatic leakage because of shear forces from tying of the sutures. Based on pancreatic surgery in animal experiments, running sutures of the pancreatic remnant may reduce bleeding and oozing of the surface of pancreatic transection, and avoid cutting the pancreatic remnant through improving its tensile strength. In addition, alimentary reconstruction by duodenojejunostomy or gastrojejunostomy may strongly affect the incidence of DGE. Some authors[7,8] have reported that Braun or Roux-en-Y reconstruction results in a lower incidence of DGE, but others have found no significant difference regarding the incidence between either of the two procedures following PD[5]. Our previous experiences concerning digestive reconstruction after gastrectomy showed that the Braun procedure probably results in better patient recovery and less DGE. Good modifications are built on values of patient health, satisfaction of doctors and patients, and low social and medical costs. Therefore, in the present study, a new modification of PD was performed: mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and additional Braun’s enteroenterostomy between the afferent and efferent limbs. Thus, the purpose of our study was to determine the clinical impact of this modification of PD.

From January 2009 to March 2014, data for 203 patients who underwent PD were prospectively documented in our database. These data were retrieved and analyzed in the current study. Of the 203 patients, 98 underwent a modified PD with Child’s gastrointestinal reconstruction plus Braun’s enteroenterostomy (details in the following surgical procedures: Technique A), and 105 received typical PD with Child’s gastrointestinal reconstruction (details in the following surgical procedures: Technique B). Only the patients operated upon by two experienced surgeons were included, to reduce the effect of a confounding variable from surgeons. Patients were excluded if they received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, had distant metastases (e.g., in the liver), or underwent vascular reconstruction. All patients were followed up, and postoperative management and complications were documented. The data collected for all patients included demographic characteristics, surgical variables (e.g., operative time and intraoperative blood loss), postoperative hospital stay, postoperative complications, reoperation rates, mortality and morbidity. All study participants, or their legal guardians, provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment. Informed consent concerning partial data used in the analysis was not obtained from the participants, because the data were analyzed anonymously. Review of patients’ records was approved by the Institutional Review Board, Shanghai 10th People’s Hospital.

Once resectability was ascertained after exploration, standard PD with distal gastrectomy was performed. After removal of samples, Child’s gastrointestinal reconstruction was recommended. The first jejunal loop was used to perform pancreatojejunostomy through the mesocolon. Pancreatojejunal anastomoses were performed, preferably in an end-to-end manner. If the pancreatic stump was too big and also not suitable for end-to-end anastomosis, an end-to-side anastomosis was performed. Subsequently, the common hepatic duct was anastomosed into the same jejunal loop in an end-to-side manner with running 4-0 PDS II (Ethicon Johnson and Johnson) sutures of the back wall and running or interrupted sutures of the front wall. The distance between hepaticojejunostomy and pancreatic anastomosis was 5-7 cm. After hepaticojejunostomy, gastrointestinal continuity was restored by gastrojejunostomy in an antecolic manner in all patients. Flow drains were placed routinely. Two different digestive reconstructive techniques were performed.

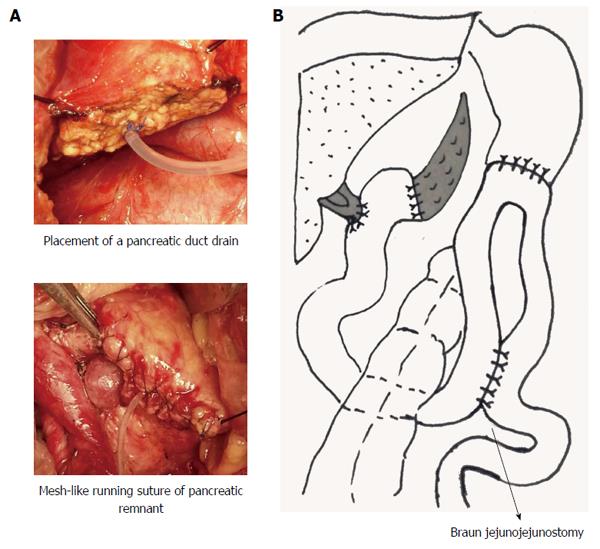

Technique A (Group A): The Child technique was performed in the standard fashion, but with some modifications. After placement of a pancreatic duct drain, the pancreatic remnant was sutured in a mesh-like running suture style with 5-0 PROLENE Polypropylene Suture. An end-to-end pancreaticojejunostomy was accomplished by a double layer interrupted suture (Figure 1A). Gastrojejunostomy was performed in an antecolic manner and an additional Braun’s enteroenterostomy between the afferent and efferent limbs was performed (Figure 1B).

Technique B (Group B): PD was performed in the standard fashion, and similar to Technique A, but without a mesh-like running suture of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy.

Postoperative management between the two groups was similar. Somatostatin analogs were administered to all patients. The median time for removal of intra-abdominal flow drains was comparable between the two groups: 9 d for Technique A and 9.5 d for Technique B.

To evaluate the efficacy of the surgical technique for pancreatojejunal anastomosis, the definition of the pancreatic fistula is important. The ISGPF definition of POPF was adopted and defined as follows[9]: the concentration of amylase from the drainage fluid was > 3 times the upper limit of serum amylase on or after postoperative day (POD) 3. POPF was divided into three types: Grade A, fistula was transient with good clinical conditions; Grade B, fistula led to infections that needed persistent drainage; and Grade C, fistula resulted in poor prognosis and was associated with reoperation. Grade B or C was regarded as clinically relevant POPF.

A suggested definition of DGE from the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) was used in our study[10]. DGE was defined as three grades: Grade A, patients could not tolerate solid oral intake after POD 7; Grade B, patients could not tolerate solid oral intake after POD 14; and Grade C, patients could not tolerate solid oral intake after POD 21. In the studies of Sakamoto et al[5] and Nikfarjam et al[7], Grade A was regarded as a non-clinically relevant complication. Grade A was affected by the timing of food service, which was affected by the surgeon’s preference and removal of nasogastric tubes. Therefore, Grades B and C DGE were considered as clinically relevant complications in our study. Other complications were defined according to Clavien and Dindo’s report[11].

Continuous values were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The χ2 test was conducted for categorical variables and Student’s t test was used for continuous variables. The influence of a given variable on the development of POPF and DGE was investigated using logistic regression.

The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Li-Wei Wang from Jilin University.

Group A group comprised 98 patients, aged 45-81 years, and Group B comprised 105 patients, aged 33-84 years. The demographic data are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between the two groups regarding sex, age, preoperative Karnofsky score, body mass index, preoperative pain, diabetes, and previous abdominal surgery. All pancreatic surgical cases were elective, and were completed by experienced surgeons. Of the 203 PD procedures, 131 were performed for pancreatic diseases: 102 were malignant pancreatic tumors, while the remaining 29 were benign tumors. Details of the histopathological diagnoses are shown in Table 2. The demographic characteristics between the two groups were comparable.

| Variable | Technique A group(n = 98) | Technique B group(n = 105) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Male/female | 57/41 | 68/37 | 0.933 | 0.334 |

| Mean age (yr) | 61.95 | 60.3 | 1.224 | 0.223 |

| Karnofsky performance status > 90 | 91 | 96 | 0.142 | 0.706 |

| Body mass index | 22.04 ± 1.40 | 21.94 ± 1.31 | 0.526 | 0.600 |

| Preoperative pain | 48 | 53 | 0.045 | 0.831 |

| Diabetes | 10 | 9 | 0.159 | 0.690 |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 8 | 10 | 0.132 | 0.716 |

| Histopathological diagnosis | Technique A group(n = 98) | Technique B group(n = 105) | Total |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma | 43 | 47 | 90 |

| Ampullary or duodenal cancer | 30 | 11 | 41 |

| Bile duct cancer | 14 | 8 | 22 |

| Neuroendocrine tumor or carcinoid tumor | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm | 2 | 6 | 8 |

| Pancreatic solid pseudopapillary tumor | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Pancreatic cystadenoma or cystadenocarcinoma | 1 | 11 | 12 |

| Common bile duct adenoma | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Duodenal adenoma | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Inflammation | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| GIST | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Pancreatic adenosquamous carcinoma | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Pancreatic tuberculosis | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pancreatic hamartoma | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pancreatic islet hyperplasia | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Pancreatic adenocarcinoma and mucinous carcinoma | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Pancreatic Acinar cell carcinoma | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Papillary carcinoma of duodenum | 0 | 4 | 4 |

Two hundred and three patients in Groups A and B received standard PD with a Child digestive reconstruction. Ninety-eight patients in Group A underwent the addition of Braun’s enteroenterostomy and a running suture of the pancreatic stump. The 105 patients in Group B did not receive Braun’s enteroenterostomy or continuous sutures. The operative time and the mean time of pancreatic anastomosis of Group A were longer than those of Group B, while operative blood loss and drainage were similar between the two groups (Table 3).

| Variable | Technique A group(n = 98) | Technique B group(n = 105) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Operating time (min) | 303.03 ± 55.24 | 281.20 ± 51.67 | 2.91 | < 0.05 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 330.89 ± 302.74 | 342.23 ± 311.34 | 0.26 | 0.79 |

| Mean time of pancreatic anastomosis (min) | 23 ± 2.83 | 16 ± 2.67 | 18.13 | < 0.01 |

| Drainage of pancreatic juice | 98 | 105 | NA | NA |

| Abdominal drainage | 98 | 105 | NA | NA |

Octreotide was administered subcutaneously in all patients. Perioperative mortality, defined as death within 30 d after surgery, was 1.0% among all patients. There was no significant difference in perioperative mortality between the two groups: the one death in Group A was from postoperative hemorrhage, while the one in Group B was from severe abdominal infection and postoperative hemorrhage. Postoperative morbidity included POPF, DGE, bile leakage, postoperative bleeding, intra-abdominal fluid collection or infection, and wound complications. The overall incidence of postoperative complications, excluding Grade A DGE, was 47.30%. Postoperative morbidity in Group B was higher than that in Group A (56.20% vs 37.75%, respectively). Reoperation was performed in one patient in Group A because of abdominal wound dehiscence, while no patient was reoperated upon in Group B. No significant difference was identified between the two groups concerning reoperation, bile leakage, intra-abdominal fluid collection or infection, and postoperative bleeding. Some complications that probably developed consequently after operative intervention but were not linked directly to the surgical technique were also compared. There were no significant differences in pneumonia, pleural effusion, or urinary tract infection between Groups A and B. No significant difference between the two groups was identified regarding hospital stay, even with a shorter stay trend in Group A (Table 4).

| Variable | Technique A group(n = 98) | Technique B group(n = 105) | t/χ2 | P value |

| Perioperative mortality | 1 | 1 | 0.002 | 0.961 |

| Re-operation | 1 | 0 | 1.077 | 0.299 |

| Overall complications | 37 | 59 | 6.911 | 0.009 |

| Breakdown of pancreatojejunostomy | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Clinically relevant POPF | 7 | 24 | 9.674 | 0.002a |

| DGE (Grade B and C) | 1 | 14 | 11.23 | 0.001a |

| Bile Leakage | 3 | 7 | 1.407 | 0.236 |

| Intra-abdominal fluid collection or infection | 20 | 22 | 0.009 | 0.924 |

| Upper GI bleeding | 4 | 5 | 0.055 | 0.814 |

| Intra-abdominal bleeding | 3 | 2 | 0.282 | 0.595 |

| Wound infection | 9 | 8 | 0.022 | 0.882 |

| Pneumonia or pleural effusion | 12 | 9 | 0.395 | 0.530 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2 | 3 | 0.006 | 0.937 |

| Hospital stay (d) | 18.45 ± 9.48 | 19.86 ± 10.04 | 1.0271 | 0.306 |

Grade B or C fistula was regarded as CR-POPF; Grades B and C DGE were regarded as clinically relevant complications. Clinically relevant POPF occurred in 15.27% of patients. Clinically relevant POPF (Grades B and C) was identified more frequently in Group B than in Group A (22.86% vs 7.14%, P = 0.002). Multivariate analysis was also done when controlling for confounding factors, and only the type of operation (Technique A) was an independent risk factor associated with clinically relevant POPF, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.266 (95%CI: 0.109-0.654, P = 0.004). Clinically relevant DGE occurred in 7.40% of patients. Higher clinically relevant DGE (Grades B and C) was identified more often in Group B than in Group A (13.33% vs 1.02%, P = 0.001). Multivariate analysis showed that Technique A was an independent risk factor for clinically relevant DGE, with an OR of 0.073 (95%CI: 0.010-0.578, P = 0.013), when controlling the risk factors clinically relevant to POPF.

The incidence of postoperative complications after PD remains high; up to 50%-60%[1,12]. Pancreatic fistula and DGE are the two most troublesome postoperative complications. Severe POPF may need reoperation and could lead to death; however, DGE is not a fatal complication after PD, but may significantly prolong hospitalization and increase costs[3]. The incidence of POPF is highly associated with the management of the pancreatic remnant, and digestive reconstruction is one of the most important determinants of postoperative DGE. Today, standard PD without mesh-like suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy between the afferent and efferent limbs, in most clinical centers, is a routine procedure for the treatment of pancreatic and periampullary malignant tumors. We modified this standard PD procedure by introducing continuous suture of the pancreatic stump with a mesh-like style and an additional Braun’s enteroenterostomy. We showed that this modified procedure significantly decreased the incidence of POPF and DGE, and it could be recommended in the clinic.

Considerable controversy exists concerning pancreatic resection. Postoperative administration of synthetic somatostatin analogs has been proposed to reduce the incidence of POPF by inhibiting exocrine pancreatic secretions; however, it is controversial. A recent meta-analysis[12] showed that somatostatin analogs might reduce perioperative morbidity, but further well-designed trials are needed to confirm this finding. Therefore, somatostatin and its analogs are used routinely for postoperative management after PD in our center. Although some studies have shown that intra-abdominal drainage does not improve postoperative outcomes after pancreatic resection[13], it still needs large and well-designed trials to confirm this. Based on our previous evidence, the incidence of intra-abdominal fluid collection or infection, even if with the placement of drainage after pancreatic resection, is up to 20%. Therefore, all patients included in the present study accepted intra-abdominal drains to detect early anastomotic complications. In addition, some surgeons prefer to place a tube into the bile duct to divert the bile after pancreatic head resection. Herzog et al[14] showed that a T tube cannot prevent biliary leakage. No tube was put into the bile duct to prevent hepaticojejunostomy leakage in any of our patients.

To date, pancreatojejunal anastomosis remains one of the most troublesome problems of pancreatic resection, and more effective skills are need to resolve it. Pancreatic duct occlusion was proposed to reduce exocrine pancreatic secretions to protect pancreatojejunal anastomosis; however, pancreatic fistulas were more frequent after duct occlusion and there was a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus in patients with duct occlusion. Drainage of the main pancreatic duct might be potentially beneficial in reducing POPF[15,16]. A pancreatic duct drain was placed in all our patients. As time has passed, some surgical modifications, such as pancreaticogastrostomy, have been proposed to reduce the incidence of POPF. Topal et al[1] reported that pancreaticogastrostomy is more efficient than pancreaticojejunostomy in reducing the incidence of POPF. In that study, 19.8% of patients in the pancreaticojejunostomy group and 8.0% in the pancreaticogastrostomy group had clinically relevant POPF[1]. We did not attempt pancreaticogastrostomy. All patients in our center underwent pancreaticojejunostomy after PD. However, a small modification for pancreaticojejunostomy was made: continuous suture of the pancreatic stump in a mesh-like style before pancreaticojejunostomy. Of 98 cases using this modified pancreaticojejunostomy, seven (7.14%) suffered from clinically relevant POPF (Group A). Standard pancreaticojejunostomy was performed in 105 cases during the same time period (Group B). There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of demographics and laboratory data. However, the incidence of POPF (Grade B or C) in Group A was significantly lower than that in Group B. Multivariate analysis also showed that Technique A was an independent risk factor for the development of POPF. Possible causes for why Technique A significantly reduced the incidence of POPF are as follows. (1) continuous suture of the pancreatic remnant ensures good hemostasis and avoids pancreatic juice extravasation from the cut surface of the pancreas; (2) the pancreatic stump, after continuous suture, has greater tensile strength, which could avoid cutting the pancreatic remnant and tangential shear forces during tying when performing pancreaticojejunostomy. This makes it easier to perform pancreaticojejunostomy in patients with soft pancreatic tissue; and (3) Braun’s enteroenterostomy in Technique A decreases biliopancreatic limb pressure and reduces the likelihood of pressure developing in the limb, which avoids corrosion and inflammation of the pancreatic remnant because of reflux of pancreatic juice, with all types of activated kinases, bile and intestinal fluid.

Braun’s enteroenterostomy in Technique A not only reduced the incidence of POPF, but also the development of postoperative DGE. Only one (1%) patient developed postoperative DGE (Grades B and C) in Group A. The incidence of DGE in Group A was significantly lower than that in Group B. Clinically relevant DGE might be initiated by an obstruction, such as anastomotic edema or stenosis[5], limb volvulus, gastric irritant effects and adhesions. In addition, any potential block from the level of gastroenterostomy after standard reconstruction could increase biliary and pancreatic anastomotic outflow pressures, resulting in increased risks of pancreatic and biliary fistula and intra-abdominal sepsis. Braun enteroenterostomy is carried out between the afferent and efferent limbs, distal to the gastroenterostomy. It potentially stabilizes the gastroenterostomy and helps prevent twisting and angulation. This anastomosis also may reduce kinking and edema of the gastroenterostomy and divert food from the afferent limb. In addition, it has been reported that Braun anastomosis might decrease bile reflux through the bypass[17] and reduce exposure of the gastric mucosa to irritants because it directs pancreatic and biliary juice away from the stomach. Moreover, Braun enteroenterostomy is reported to reduce loop obstruction[18] and ease the passage of food. Meanwhile, Qu et al[19] reported that pancreatic fistula is a clinical risk factor predictive of DGE. Therefore, our lower incidence of DGE in Group A might also have been associated with the lower incidence of POPF because of continuous suture of the pancreatic stump with mesh-like style and Braun’s enteroenterostomy.

The postoperative morbidity rate after PD is 50%-60%, while only a small number of complications, such as POPF and DGE, significantly alter the postoperative course and hospital stay. Continuous suture of the pancreatic stump with mesh-like style and Braun’s enteroenterostomy during PD significantly reduced the postoperative complications, including clinically relevant POPF and DGE. These surgical techniques are safe and effective, easily mastered by surgeons, improve the outcomes of PD and offer major economic and social benefits. A randomized control trial is required to confirm the above conclusions; however, from the current data, an additional mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy, which reduces the incidence of postoperative complications and is beneficial for patients, could be recommended.

There is still a high incidence of complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD); therefore, new techniques need to be developed to decrease postoperative morbidity.

Running suture of the pancreatic remnant may reduce postoperative pancreatic fistula (POPF) by inhibiting bleeding and oozing of the surface of the pancreatic transection. Alimentary reconstruction, such as Braun or Roux-en-Y reconstruction, may strongly affect the incidence of postoperative complications; however, controversy remains. Whether an additional mesh-like running suturing for the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy during PD could reduce the incidence of postoperative complications is unclear.

An additional mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy during PD was independently associated with decreased clinically relevant POPF and delayed gastric emptying (DGE), with an odds ratio of 0.266 (95%CI: 0.109-0.654, P = 0.004) for clinically relevant POPF and 0.073 (95%CI: 0.010-0.578, P = 0.013) for clinically relevant DGE. It reduced the incidence of postoperative complications and was beneficial for patients.

An additional mesh-like running suturing of the pancreatic remnant and Braun’s enteroenterostomy is recommended, which reduces the incidence of postoperative complications and is beneficial for patients.

Braun’s enteroenterostomy is a type of anastomosis between the afferent and efferent limbs.

The paper provides a practical and useful modification for pancreaticoduodenectomy. The topic is very interesting, the results are applicable and the conclusions are valuable.

P- Reviewer: Gong JS, Liu ZW S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Topal B, Fieuws S, Aerts R, Weerts J, Feryn T, Roeyen G, Bertrand C, Hubert C, Janssens M, Closset J. Pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic or periampullary tumours: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 212] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Inchauste SM, Lanier BJ, Libutti SK, Phan GQ, Nilubol N, Steinberg SM, Kebebew E, Hughes MS. Rate of clinically significant postoperative pancreatic fistula in pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2012;36:1517-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hackert T, Bruckner T, Dörr-Harim C, Diener MK, Knebel P, Hartwig W, Strobel O, Fritz S, Schneider L, Werner J. Pylorus resection or pylorus preservation in partial pancreatico-duodenectomy (PROPP study): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2013;14:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nikfarjam M, Kimchi ET, Gusani NJ, Shah SM, Sehmbey M, Shereef S, Staveley-O’Carroll KF. A reduction in delayed gastric emptying by classic pancreaticoduodenectomy with an antecolic gastrojejunal anastomosis and a retrogastric omental patch. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1674-1682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sakamoto Y, Yamamoto Y, Hata S, Nara S, Esaki M, Sano T, Shimada K, Kosuge T. Analysis of risk factors for delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after 387 pancreaticoduodenectomies with usage of 70 stapled reconstructions. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1789-1797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rayar M, Sulpice L, Meunier B, Boudjema K. Enteral nutrition reduces delayed gastric emptying after standard pancreaticoduodenectomy with child reconstruction. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1004-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Nikfarjam M, Houli N, Tufail F, Weinberg L, Muralidharan V, Christophi C. Reduction in delayed gastric emptying following non-pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy by addition of a Braun enteroenterostomy. JOP. 2012;13:488-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hochwald SN, Grobmyer SR, Hemming AW, Curran E, Bloom DA, Delano M, Behrns KE, Copeland EM, Vogel SB. Braun enteroenterostomy is associated with reduced delayed gastric emptying and early resumption of oral feeding following pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:351-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3514] [Article Influence: 175.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 10. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2332] [Article Influence: 129.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205-213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18532] [Cited by in RCA: 24856] [Article Influence: 1183.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gurusamy KS, Koti R, Fusai G, Davidson BR. Somatostatin analogues for pancreatic surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD008370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rondelli F, Desio M, Vedovati MC, Balzarotti Canger RC, Sanguinetti A, Avenia N, Bugiantella W. Intra-abdominal drainage after pancreatic resection: is it really necessary? A meta-analysis of short-term outcomes. Int J Surg. 2014;12 Suppl 1:S40-S47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Herzog T, Belyaev O, Bakowski P, Chromik AM, Janot M, Suelberg D, Uhl W, Seelig MH. The difficult hepaticojejunostomy after pancreatic head resection: reconstruction with a T tube. Am J Surg. 2013;206:578-585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Minagawa N, Tamura T, Kanemitsu S, Shibao K, Higure A, Yamaguchi K. Intermittent negative pressure external drainage of the pancreatic duct reduces the incidence of postoperative pancreatic fistula after pancreaticojejunostomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:1841-1846. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Wang Q, He XR, Tian JH, Yang KH. Pancreatic duct stents at pancreaticoduodenectomy: a meta-analysis. Dig Surg. 2013;30:415-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Vogel SB, Drane WE, Woodward ER. Clinical and radionuclide evaluation of bile diversion by Braun enteroenterostomy: prevention and treatment of alkaline reflux gastritis. An alternative to Roux-en-Y diversion. Ann Surg. 1994;219:458-465; discussion 465-466. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Kim DJ, Lee JH, Kim W. Afferent loop obstruction following laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with Billroth-II gastrojejunostomy. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;84:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Qu H, Sun GR, Zhou SQ, He QS. Clinical risk factors of delayed gastric emptying in patients after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2013;39:213-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |