Published online Mar 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2719

Peer-review started: September 23, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 28, 2014

Accepted: December 5, 2014

Article in press: December 8, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2015

Processing time: 167 Days and 4.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and safety of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in treating acute bleeding of gastric varices in children.

METHODS: The retrospective study included 21 children with 47 episodes of active gastric variceal bleeding who were treated by endoscopic injection of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate at Asan Medical Center Children’s Hospital between August 2004 and December 2011. To reduce the risk of embolism, each injection consisted of 0.1-0.5 mL of 0.5 mL N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate diluted with 0.5 or 0.8 mL Lipiodol. The primary outcome was incidence of hemostasis after variceal obliteration and the secondary outcome was complication of the procedure.

RESULTS: The 21 patients experienced 47 episodes of active gastric variceal bleeding, including rebleeding, for which they received a total of 52 cyanoacrylate injections. Following 42 bleeding episodes, hemostasis was achieved after one injection and following five bleeding episodes it was achieved after two injections. The mean volume of each single aliquot of cyanoacrylate injected was 0.3 ± 0.1 mL (range: 0.1-0.5 mL). Injection achieved hemostasis in 45 of 47 (95.7%) episodes of acute gastric variceal bleeding. Eleven patients (52.4%) developed rebleeding events, with the mean duration of hemostasis being 11.1 ± 11.6 mo (range: 1.0-39.2 mo). No treatment-related complications such as distal embolism were noted with the exception of abdominal pain in one patient (4.8%). Among four mortalities, one patient died of variceal rebleeding.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopic variceal obliteration using a small volume of aliquots with repeated cyanoacrylate injection was an effective and safe option for the treatment of gastric varices in children.

Core tip: This is the first pediatric study using cyanoacrylate injection for acute gastric bleeding. The findings support its applicability to pediatric group.

- Citation: Oh SH, Kim SJ, Rhee KW, Kim KM. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate injection for the treatment of gastric varices in children. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(9): 2719-2724

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i9/2719.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i9.2719

Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) has been shown to be effective and safe as first-line treatment of esophageal variceal bleeding in adults and children[1-3]. No method has become standardized, however, for the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in children[1]. There have been no multicenter randomized controlled trials (RCTs), and only a few single-center RCTs, in adults[4-6]. The Baveno V consensus suggests endoscopic variceal obliteration (EVO) with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) and EVL as first-line treatments for gastroesophageal varices (GOV) and for isolated gastric varices in adults[1].

Although pediatric experts have also recommended EVO with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for the management of bleeding from GOV in children, evidence for the management of gastric variceal bleeding in children is limited to case reports and uncontrolled case series[2]. In addition, the natural course and anatomy of gastric varices were only recently understood due to the development of interventional radiological procedures[7-9]. As mortality and rebleeding rates are higher for gastric than for esophageal varices[10-12], endoscopic treatment guidelines must be established for gastric variceal bleeding in children. EVL is often not applicable to small children because their small pharynxes cannot adapt to conventional banding devices, resulting in esophageal injury from overtubes[13].

Despite EVO with cyanoacrylate being more applicable to small children[14], caution is needed prior to its use for gastric varices in children. Fatal complications, such as systemic embolism, have been observed in patients treated with cyanoacrylate for variceal bleeding[15,16]. This study evaluated the hemostatic effectiveness and safety of EVO with cyanoacrylate in the treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in children.

Between August 2004 and December 2011, 21 patients with gastric varices were managed using EVO with cyanoacrylate within 48 h after conservative management of gastric variceal bleeding at Asan Medical Center Children’s Hospital. These 21 patients consisted of 8 boys and 13 girls, of median age 9 years (range: 9 mo-18 years). The mean height and weight of the children were 120 ± 26 cm and 21 ± 14.4 kg, respectively. Informed, written consent was obtained from the parents of all the patients and the study was approved by our Internal Review Board.

Causes of portal hypertension included biliary atresia in nine patients (43%), extrahepatic portal vein obstruction (EHPVO) in five patients (24%), congenital hepatic fibrosis in two patients (10%), and Wilson’s disease, autoimmune hepatitis, Budd-Chiari syndrome, hepatic vein occlusion, and liver cirrhosis due to cytomegalovirus hepatitis in one each of the remaining five patients.

Treatments prior to EVO included EVL in 10 patients (47.6%) and endoscopic injection sclerotherapy (EIS) with ethanolamine in two (9.5%). In particular, five of the younger and smaller patients (23.8%) failed the EVL due to difficulties in approach. The mean pediatric end-stage liver disease (PELD) score for the 16 patients younger than 12 years was 3.9 ± 12.8 (range: -7-47), and the mean model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score for the five patients who were 12 years or older was 12.0 ± 3.0 (range: 9-17). Of the 21 patients, 16 (76.2%) were diagnosed with GOV type 1 (GOV1) and five with GOV2, with none having isolated gastric varices (IGV) according to the Sarin classification[17]. Varices were categorized according to their size as grade I-IV (I, < 3 mm; II, 4-6 mm; III, 7-10 mm; IV, > 10 mm). Most varices were of the largest size at the time of the first procedure, with 12 patients (57.1%) having grade III or IV varices. Morphological classification showed that 15 patients (71.4%) could be classified as having Form 2 (F2, tubular and beaded) and six (28.6%) as having Form 3 (F3, nodular) varices (Table 1)[18]. Esophageal varices of ≥ grade II were noted among 16 (76.1%) children with GOV1 and GOV2.

| Clinical characteristics | n = 21 |

| Male/female | 8 (38.0)/13 (62.0) |

| Age (yr), median | 8.7 (0.8-17.7) |

| Height (cm), mean | 120 ± 26 |

| Weight (kg), mean | 21 ± 14.4 |

| Etiology of the gastric varices | |

| Biliary atresia | 9 (42.8) |

| Portal vein thrombosis | 5 (23.7) |

| Congenital hepatic fibrosis | 2 (9.5) |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 1 (4.8) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 (4.8) |

| Wilson’s disease | 1 (4.8) |

| Hepatic vein obstruction | 1 (4.8) |

| Liver cirrhosis due to cytomegalovirus infection | 1 (4.8) |

| mean PELD score (< 12 yr), mean | 3.9 ± 12.8 |

| mean MELD score (≥ 12 yr), mean | 12.0 ± 3.0 |

| Receiving β-blocker medication | 8 (38.1) |

| Sarin classification of the gastroesophageal varices | |

| GOV1 | 16 (76.2) |

| GOV2 | 5 (23.8) |

| Grade of the gastric varices | |

| Grade I | 0 (0) |

| Grade II | 9 (42.9) |

| Grade III | 8 (38.1) |

| Grade IV | 4 (19.0) |

| Form of the gastric varices | |

| F1 | 0 (0) |

| F2 | 15 (71.4) |

| F3 | 6 (28.6) |

Active gastric variceal bleeding (visible bleeding or clotted blood over a gastric varix) was confirmed within 24 h using diagnostic esophagogastroscopy, in addition to the presence of large gastric varices and other sources of bleeding that are often present with hematemesis and melena. All patients received EVO as the secondary prophylaxis. Before active gastric bleeding developed, eight patients (38.1%) were taking β-blockers as primary prophylaxis.

EVO is not a well-established procedure, especially in children, so it was performed only in children who had developed gastric variceal bleeding. Efforts were focused on minimizing the risk of distant emboli, especially when treating small varices. The location and type of each gastric varix was endoscopically evaluated before the procedure, and the target varices were determined[8,9]. The injection catheter was inserted through the endoscope and the needle was inserted directly into each gastric varix. It was difficult to determine flow direction, even with GOV1, most of which drains into esophageal varices[8,9]. Although fluoroscopic examination and endoscopic ultrasonography could determine the size and location of collateral blow flow, neither was performed.

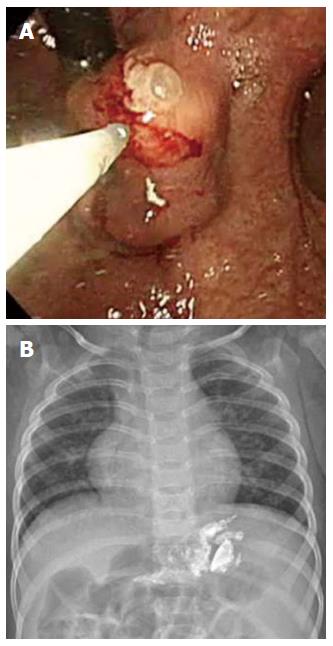

The EVO protocol in the present study was based on that used to treat adults[19]. Cyanoacrylate was repeatedly injected until the varices began to occlude, as determined by probing with a blunt probe. Cyanoacrylate injections were performed using the GIF series (Olympus Co., Tokyo, Japan) and disposable 23-gauge injection needle catheters (1.650 mm in length) (Figure 1). Each injection consisted of 0.1-0.5 mL of 0.5 mL N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate mixed with 0.5 or 0.8 mL Lipiodol (cyanoacrylate:Lipidol=1:1 or 1:1.6) (Guerbet, Aulnay-Sous-Bois, France). As small injection volumes are recommended when treating adults[19], a small aliquot of a thick mixture of cyanoacrylate was preferentially used in treating children. It was also to minimize the number of injections and the amount of cyanoacrylate administered. The presence of distant emboli following treatment was reevaluated on chest and abdominal X-rays.

Successful hemostasis of active gastric variceal bleeding has been defined, according to the Baveno V criteria[1,2] as an absence of upper gastrointestinal bleeding for the first 120 h (5 d) after cyanoacrylate injection. Unsuccessful hemostasis was defined as death or the need to change the therapy due to (1) fresh hematemesis or naso-gastric aspiration that removed ≥ 100 mL of fresh blood ≥ 2 h after the procedure; (2) development of hypovolemic shock; or (3) a 3 g/L drop in hemoglobin within any 24 h period in the absence of transfusions[2,20].

Rebleeding was defined as unsuccessful secondary prophylaxis, clinically significant rebleeding from portal hypertensive sources after day 5, or recurrent melena or hematemesis resulting in (1) hospital admission; (2) blood transfusion; (3) a 3 g/L drop in hemoglobin concentration; or (4) death within 6 wk. Treatment-related complications included (1) unplanned hospitalization or additional inpatient management; (2) death directly attributed to treatment; (3) treatment-associated infection such as pneumonia or peritonitis; (4) gastric perforation; and (5) distant embolization.

The 21 patients experienced 47 episodes of active gastric variceal bleeding, including rebleeding, for which they received a total of 52 cyanoacrylate injections (mean number of sessions per episode 1.1 ± 0.3). Following 42 bleeding episodes, hemostasis was achieved after one injection and following five bleeding episodes it was achieved after two injections. The mean volume of each single aliquot of cyanoacrylate injected was 0.3 ± 0.1 mL (range: 0.1-0.5 mL). Successful hemostasis was achieved after 45 of the 47 episodes (95.7%). In one of the two patients who failed to achieve bleeding control, EVO was interrupted due to hypotension caused by massive bleeding from a large fundal varix, whereas the second patient presented with a double aortic arch and tracheoesophageal narrowing, resulting in a failed endoscopic approach. The mean follow-up period was 30.2 ± 25.5 mo (range: 0.1-101.0 mo). Eleven (52.4%) patients developed rebleeding events, and the mean duration of hemostasis after EVO was 11.1 ± 11.6 mo (range: 1.0-39.2 mo). Five patients (23.8%) developed rebleeding episodes within one year. The success rate of secondary prophylaxis after primary EVO was 47.6% (Table 2).

| No. of sessions | Value |

| 1 | 42 (89.3) |

| 2 | 5 (10.7) |

| ≥ 3 | 0 (0) |

| mean no. of sessions | 1.1 ± 0.3 |

| mean single aliquot of cyanoacrylate injection volume (mL) (range) | 0.3 ± 0.1 (0.1-0.5) |

| Successful hemostasis | 45 (95.7)/47 (95.7) |

| mean follow-up duration (mo) | 30.2 ± 25.5 |

| Number of rebleeding episodes | 11 (52.4)/21 (52.4) |

| mean duration of hemostasis after EVO (mo) | 11.1 ± 11.6 |

| Number of patients with rebleeding within < 12 m | 5 (23.8)/21 (23.8) |

| Treatment-related complications | 1 (4.8)/21 (4.8) |

Treatment-related complications developed in only one patient (4.8%), whose hospitalization had to be extended because of abdominal pain and distension. Other complications, such as treatment-associated infection, gastric perforation, and distant emboli, did not occur. One patient was first suspected of having a pulmonary embolism, but it was later shown to be a pulmonary abscess and fistula between the distal esophagus and left lower lung that was complicated by previous esophageal variceal band ligation. During the follow-up, three patients received liver transplants, one underwent a Rex-shunt operation, and four died. Causes of death included variceal rebleeding in one patient, anaphylactic shock in one patient, and progression to hepatic failure in two patients.

In general, EIS and EVL have been used to treat acute bleeding from GOV in children[21,22]. However, the applicability of these treatment modalities for GOV in small children is limited due to insufficient evidence, technical difficulties, low success rates, and frequent complications[13,23-25]. For example, a banding device has not been developed for small children, whereas the overtubes of conventional devices may cause esophageal injury[13]. Moreover, the device tip often does not reach the bleeding loci of GOV due to the angled position of the fundus in children[23]. In addition, EIS is problematic in controlling acute GOV bleeding, especially from fundal varices (GOV2 and IGV1), with lower primary hemostasis rates[24].

N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) is a tissue adhesive agent that rapidly hardens from a liquid form to a solid upon contact with hydroxyl ions in water[26]. Intravariceal injection of this compound, therefore, causes the varix to occlude rapidly upon contact with blood[23]. Although there have been only three case series on the use of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate for gastric varices in children[14,22,27], studies in adults suggest that N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate can be a promising alternative to EVL and EIS for controlling acute GOV bleeding. Recently, two large retrospective studies reported primary hemostasis rates of 95%-100% after cyanoacrylate injection for the control of acute GOV bleeding in adults[19,28]. In addition, a RCT found that the success rate of primary hemostasis in patients with acute GOV bleeding was higher with cyanoacrylate injection than with EIS (89% vs 62%)[6], and two RCTs showed that the success rates of primary hemostasis for adults with acute GOV bleeding were similar or higher for cyanoacrylate injection than for EVL (87%-93% vs 45%-93%)[4,29].

We found that the success rate of primary hemostasis in children was 95.7% in this study, similar to recent findings in adults. Cyanoacrylate was found to be effective in treating esophagogastric varices in children < 2 years old and < 10 kg; in that study, four children (19%) underwent EVO instead of EVL because of a device entry failure[14]. The overall rebleeding rate (52.4%) in this study was as high as the rate after EIS in adults (25%-70%)[30-32]. However, the rebleeding rate was 23.8% one year after the first injection of cyanoacrylate, similar to rebleeding rates of 22%-41% after 15-24 mo in adults[6,33,34]. Therefore, the efficacy of cyanoacrylate injection in primary hemostasis of acute GOV bleeding in children was high, although methods are needed to reduce the high rebleeding rate.

Several precautions must be taken during the endoscopic use of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate. Careful techniques are needed to prevent injury to the endoscopist’s eye and to prevent blocking the biopsy channel of the endoscope. In addition, excessive dilution of cyanoacrylate carries a risk of fatal cerebral or pulmonary embolism. Small, relatively concentrated aliquots are therefore recommended for injection[19,35,36]. Most patients in this present study were injected with a 1:1 mixture of cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol, and most were initially injected with 0.25-0.5 mL cyanoacrylate to prevent systemic embolisms. X-ray evaluation after the procedure showed the presence of Lipiodol in the upper esophagus along the esophageal varix, so small children were injected with a very small aliquot (0.2 mL) of a thick mixture of cyanoacrylate and Lipiodol. Distant emboli can be prevented by injecting small aliquots multiple times until variceal occlusion is achieved. No patient in the present study experienced distant emboli.

EVO-related complications and systemic embolic events, such as cerebral stroke, portal vein embolization, splenic infarction, and pulmonary embolism, have been reported in 4.6% of patients, along with bleeding ulcers in 2%-8% and sepsis in 1%-14%. These complications, however, are not usually life-threatening rates and are generally reversible. More frequently, mild complications, such as pyrexia (10%-35%) and chest or abdominal pain (5%-30%), have been reported[37]. Of our 21 patients, only one developed abdominal pain and distension, with no other patient experiencing complications. Hydrolization of cyanoacrylate results in the production of toxic substances, such as formaldehyde[38], which has been shown carcinogenic in an animal model[39]. A similar tissue adhesive, 2-octyl cyanoacrylate, is available, showing similar efficacy and safety as N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in controlling GOV bleeding in adults[40].

Portal hypertension in children is usually caused by biliary atresia and EHPVO and may have clinical consequences in the development of esophageal/gastric varices. Fortunately, the mortality rate (0%-8%) due to variceal bleeding is not as high in children as in adults[41]. Approximately 40% of children with biliary atresia develop variceal bleeding within 5 years, compared with 49% of patients < 16 years old and 76% of patients < 24 years old with EHPVO. Of 139 children with biliary atresia, 125 (90%) were diagnosed with portal hypertension; of the latter, 87 (70%) developed varices and 25 (20%) developed variceal bleeding[42]. In adults, the incidence of gastric varices (14%-36%) is lower than that of esophageal varices, but gastric varices result in more severe bleeding, a higher mortality rate (25%-55%), and a higher incidence of rebleeding (26%-89%)[10-12]. Currently, there are not enough pediatric studies on this issue.

In conclusion, this study suggests that endoscopic vascular obliteration using N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate may be effective in children for the initial hemostasis of bleeding due to gastric varices, with a low rate of complications. This study was limited, however, by its inclusion of a small number of patients. The efficacy and safety of tissue adhesives, such as N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate and 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate, for acute gastric variceal bleeding require validation in large, multicenter RCTs.

Gastric varix causes more severe bleeding and higher mortality than esophageal varix in children. However, few studies on treating acute gastric variceal bleeding are done in children.

This retrospective pediatric study is the first study to evaluate cyanoacrylate injection to treat acute gastric variceal bleeding in children.

Repeated injections of a small volume of cyanoacrylate treated gastric variceal bleeding without embolism.

Cyanoacrylate injection may be applicable to treatment of acute gastric variceal bleeding in children.

N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (histoacryl) is a tissue adhesive agent that rapidly hardens upon contact with water.

This is a retrospective study of Cyanoacrylate injection for varices in the pediatric patients. The limitation was a small number of patients enrolled, however, interesting results.

P- Reviewer: Lim YS, Nakamura S, Prachayakul V S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | de Franchis R. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1066] [Cited by in RCA: 1025] [Article Influence: 68.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shneider BL, Bosch J, de Franchis R, Emre SH, Groszmann RJ, Ling SC, Lorenz JM, Squires RH, Superina RA, Thompson AE, Mazariegos GV; expert panel of the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Portal hypertension in children: expert pediatric opinion on the report of the Baveno v Consensus Workshop on Methodology of Diagnosis and Therapy in Portal Hypertension. Pediatr Transplant. 2012;16:426-437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim SJ, Kim KM. Recent trends in the endoscopic management of variceal bleeding in children. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2013;16:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Lo GH, Lai KH, Cheng JS, Chen MH, Chiang HT. A prospective, randomized trial of butyl cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation in the management of bleeding gastric varices. Hepatology. 2001;33:1060-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 332] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, Chen MH, Lai KH, Hsu PI, Lin CK, Chan HH, Pan HB. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39:679-685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sarin SK, Jain AK, Jain M, Gupta R. A randomized controlled trial of cyanoacrylate versus alcohol injection in patients with isolated fundic varices. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1010-1015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kiyosue H, Mori H, Matsumoto S, Yamada Y, Hori Y, Okino Y. Transcatheter obliteration of gastric varices. Part 1. Anatomic classification. Radiographics. 2003;23:911-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao LQ, He W, Ji M, Liu P, Li P. 64-row multidetector computed tomography portal venography of gastric variceal collateral circulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1003-1007. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Kiyosue H, Ibukuro K, Maruno M, Tanoue S, Hongo N, Mori H. Multidetector CT anatomy of drainage routes of gastric varices: a pictorial review. Radiographics. 2013;33:87-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | El-Rifai N, Mention K, Guimber D, Michaud L, Boman F, Turck D, Gottrand F. Gastropathy and gastritis in children with portal hypertension. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;45:137-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garcia-Tsao G, Groszmann RJ, Fisher RL, Conn HO, Atterbury CE, Glickman M. Portal pressure, presence of gastroesophageal varices and variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 1985;5:419-424. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Vargas HE, Gerber D, Abu-Elmagd K. Management of portal hypertension-related bleeding. Surg Clin North Am. 1999;79:1-22. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Price MR, Sartorelli KH, Karrer FM, Narkewicz MR, Sokol RJ, Lilly JR. Management of esophageal varices in children by endoscopic variceal ligation. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:1056-1059. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Rivet C, Robles-Medranda C, Dumortier J, Le Gall C, Ponchon T, Lachaux A. Endoscopic treatment of gastroesophageal varices in young infants with cyanoacrylate glue: a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1034-1038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Saracco G, Giordanino C, Roberto N, Ezio D, Luca T, Caronna S, Carucci P, De Bernardi Venon W, Barletti C, Bruno M. Fatal multiple systemic embolisms after injection of cyanoacrylate in bleeding gastric varices of a patient who was noncirrhotic but with idiopathic portal hypertension. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:345-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park WG, Yeh RW, Triadafilopoulos G. Injection therapies for variceal bleeding disorders of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:313-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sarin SK, Kumar A. Gastric varices: profile, classification, and management. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:1244-1249. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hashizume M, Kitano S, Yamaga H, Koyanagi N, Sugimachi K. Endoscopic classification of gastric varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:276-280. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Seewald S, Ang TL, Imazu H, Naga M, Omar S, Groth S, Seitz U, Zhong Y, Thonke F, Soehendra N. A standardized injection technique and regimen ensures success and safety of N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection for the treatment of gastric fundal varices (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68:447-454. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Stiegmann GV, Goff JS, Sun JH, Davis D, Silas D. Technique and early clinical results of endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). Surg Endosc. 1989;3:73-78. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Mitsunaga T, Yoshida H, Kouchi K, Hishiki T, Saito T, Yamada S, Sato Y, Terui K, Nakata M, Takenouchi A. Pediatric gastroesophageal varices: treatment strategy and long-term results. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1980-1983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Itha S, Yachha SK. Endoscopic outcome beyond esophageal variceal eradication in children with extrahepatic portal venous obstruction. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;42:196-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sasaki T, Hasegawa T, Nakajima K, Tanano H, Wasa M, Fukui Y, Okada A. Endoscopic variceal ligation in the management of gastroesophageal varices in postoperative biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1628-1632. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Korula J, Chin K, Ko Y, Yamada S. Demonstration of two distinct subsets of gastric varices. Observations during a seven-year study of endoscopic sclerotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:303-309. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Sarin SK. Long-term follow-up of gastric variceal sclerotherapy: an eleven-year experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;46:8-14. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Fuster S, Costaguta A, Tobacco O. Treatment of bleeding gastric varices with tissue adhesive (Histoacryl) in children. Endoscopy. 1998;30:S39-S40. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, Cai FC, Huang QY, Linghu EQ, Li W, Chai GJ, Sun GH, Mao YP. Treatment of gastric varices by endoscopic sclerotherapy using butyl cyanoacrylate: 10 years’ experience of 635 cases. Chin Med J (Engl). 2007;120:2081-2085. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Tan PC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Liu TT, Lee FY, Chang FY, Lee SD. A randomized trial of endoscopic treatment of acute gastric variceal hemorrhage: N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate injection versus band ligation. Hepatology. 2006;43:690-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Oho K, Iwao T, Sumino M, Toyonaga A, Tanikawa K. Ethanolamine oleate versus butyl cyanoacrylate for bleeding gastric varices: a nonrandomized study. Endoscopy. 1995;27:349-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chang KY, Wu CS, Chen PC. Prospective, randomized trial of hypertonic glucose water and sodium tetradecyl sulfate for gastric variceal bleeding in patients with advanced liver cirrhosis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:481-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Chang KY, Wu CS, Chen PC. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding fundic varices with 50% glucose injection. Endoscopy. 1996;28:398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Marques P, Maluf-Filho F, Kumar A, Matuguma SE, Sakai P, Ishioka S. Long-term outcomes of acute gastric variceal bleeding in 48 patients following treatment with cyanoacrylate. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:544-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Joo HS, Jang JY, Eun SH, Kim SK, Jung IS, Ryu CB, Kim YS, Kim JO, Cho JY, Kim YS. [Long-term results of endoscopic histoacryl (N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate) injection for treatment of gastric varices--a 10-year experience]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2007;49:320-326. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Binmoeller KF, Soehendra N. “Superglue”: the answer to variceal bleeding and fundal varices? Endoscopy. 1995;27:392-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tan YM, Goh KL, Kamarulzaman A, Tan PS, Ranjeev P, Salem O, Vasudevan AE, Rosaida MS, Rosmawati M, Tan LH. Multiple systemic embolisms with septicemia after gastric variceal obliteration with cyanoacrylate. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:276-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Huang YH, Yeh HZ, Chen GH, Chang CS, Wu CY, Poon SK, Lien HC, Yang SS. Endoscopic treatment of bleeding gastric varices by N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl) injection: long-term efficacy and safety. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:160-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vinters HV, Galil KA, Lundie MJ, Kaufmann JC. The histotoxicity of cyanoacrylates. A selective review. Neuroradiology. 1985;27:279-291. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Reiter A. [Induction of sarcomas by the tissue-binding substance Histoacryl-blau in the rat]. Z Exp Chir Transplant Kunstliche Organe. 1987;20:55-60. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Rengstorff DS, Binmoeller KF. A pilot study of 2-octyl cyanoacrylate injection for treatment of gastric fundal varices in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:553-558. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Molleston JP. Variceal bleeding in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:538-545. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Duché M, Ducot B, Tournay E, Fabre M, Cohen J, Jacquemin E, Bernard O. Prognostic value of endoscopy in children with biliary atresia at risk for early development of varices and bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1952-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |