Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2573

Peer-review started: May 26, 2014

First decision: July 9, 2014

Revised: July 21, 2014

Accepted: September 16, 2014

Article in press: September 16, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 281 Days and 7.6 Hours

A 67-year-old female presented with a primary hepatic gastrointestinal stromal tumor that was detected by computed tomography and diagnosed based on histopathological and genetic analyses. The tumor was microscopically composed of spindle cells and epithelioid cells, and immunohistochemistry results showed positive staining for CD117 and CD34 expression. A genetic analysis revealed a heterozygous point mutation and deletion in exon 11 of c-KIT. After an R0 resection, imatinib mesylate was administered for 1 year until its use was discontinued due to severe side effects. Two years after the original operation, the tumor recurred in the residual liver and was completely resected again. Imatinib mesylate was administered for 2 years until it was replaced by sunitinib malate because of disease progression. The patient has survived for 53 mo after undergoing a sequential therapy consisting of surgical excision, imatinib and sunitinib.

Core tip: The tumor was detected by computed tomography and diagnosed based on histopathological and genetic analyses. Metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors were excluded using computed tomography, ultrasound, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. The patient was treated with an extended sequential therapy consisting of surgery, imatinib mesylate, and sunitinib malate. The patient has survived for 53 mo after the start of therapy.

- Citation: Lin XK, Zhang Q, Yang WL, Shou CH, Liu XS, Sun JY, Yu JR. Primary gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver treated with sequential therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2573-2576

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2573.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2573

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common abdominal tumors of mesenchymal origin. GISTs primarily occur in the gastrointestinal tract and frequently contain a gain-of-function mutation of the KIT or PDGFRA genes[1]. Currently, diagnosis of GISTs is based on histopathological features, including the immunohistochemical staining of CD117, DOG-1, CD34, SMA, desmin and S-100. A minor subset of GISTs occur in other areas of the body, such as the mesentery, omentum, retroperitoneum, pancreas, uterus, gallbladder and liver[2-5], and are referred to as “extra-gastrointestinal stromal tumors”. Here, we report a case of primary GIST of the liver.

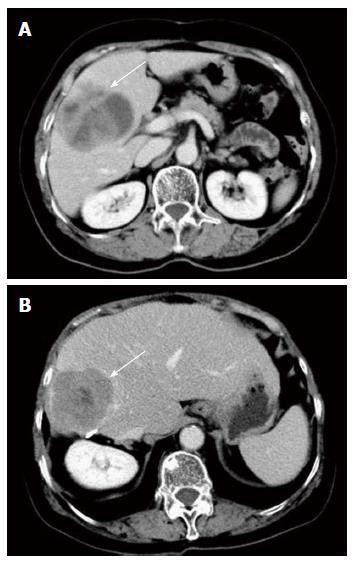

A 67-year-old female complained of fatigue for 6 mo without any abdominal symptoms. The patient had a history of hypertension, gastritis, and hysteromyoma. Additionally, she had undergone a cholecystectomy at the age of 55 years. The abdominal physical examination was unremarkable. The levels of tumor markers, such as carbohydrate antigen 199, carbohydrate antigen 125, carcinoembryonic antigen and α-fetoprotein (AFP), were all normal. Liver function tests were normal. An enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 7.4 cm × 6.2 cm solid-cystic mass in the right hepatic lobe. However, no other abdominal neoplasm was evident (Figure 1A). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy were performed before resection; however, no tumor was found.

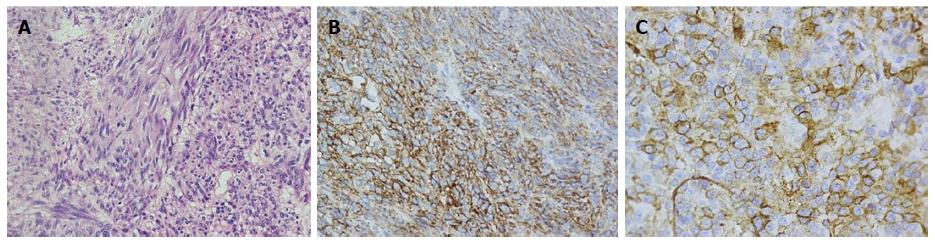

The hepatic mass was excised in August 2009. No other masses were found during the operation. A postoperative abdomen ultrasound (US) revealed no other lesions in the liver. Pathologically, the margins of resection were negative, and the tumor was composed of spindle cells and epithelioid cells with high mitotic activity (8/50 HPF) (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemical staining for CD117, CD34, desmin, SMA, CK19, HMB45, and AFP revealed positive results for CD117 and CD34 (Figure 2B and C). A heterozygous mutation was detected in a hot spot region of c-KIT exon 11. Specifically, codon 550 was mutated (AAA→ATA), and codons 551-555 were deleted (CCC-ATG-TAT-GAA-GTA).

Imatinib mesylate was administered at 400 mg per day for 2 mo, beginning 1 mo after surgery. However, the patient experienced severe musculoskeletal pain from the medication, and the dosage was reduced to 200 mg per day for 1 year. In September 2011, a 6 cm × 5 cm lesion was detected in the residual right liver after a routine CT examination. The tumor was completely resected again (Figure 1B). The results of immunohistochemical staining and genetic analysis of the specimen were consistent with the initial mass. Thus, recurrent hepatic neoplasia was diagnosed, and 200 mg of imatinib mesylate per day was administered beginning in October 2011.

In October 2013, a 6 cm × 5 cm mass was detected in the right iliac fossa using CT. An emission CT revealed several bony metastases in the thoracic vertebrae, lumbar vertebrae and sacrum. Based on the disease progression while undergoing 2 years of imatinib mesylate therapy, the patient was switched to 37.5 mg of sunitinib malate per day.

GISTs are the most common gastrointestinal mesenchymal tumors and often occur due to a KIT or PDGFRA gene mutation. GISTs are similar to interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) pacemaker cells in the gut musculature; thus, GISTs are considered to originate from ICCs[6]. Furthermore, some researchers have observed “ICC-like” interstitial cells with a similar structure and function to ICCs in organs outside of the gastrointestinal tract[7]. Other studies have suggested that GISTs originate from a group of undifferentiated cells, such as stem cells or primitive ancestor cells, and then differentiate into ICCs[8]. It has been recently reported that ICCs, ICC-like cells and primitive ancestor cells are present in the gallbladder wall, myometrium, and pancreas, respectively[3,4,9]. Rusu et al[10] discovered the existence of portal interstitial cells of Cajal in the portal space, portal septa and periphery of the hepatic lobules based on immunohistochemical staining of human hepatic tissue.

In cases of hepatic GISTs, metastases from GISTs and other primary hepatic tumors must be excluded. We believe the tumor in this case was a primary hepatic GIST because the intra-operative inspection and the imaging examinations, including CT, US, EGD and colonoscopy, revealed that the tumor was completely limited to the liver. Additionally, histopathological and genetic analyses strongly supported a GIST diagnosis. Finally, a lack of AFP, CK19, and HMB-45 expression distinguished the mass from a carcinoma, an epithelioid angiomyolipoma, or a hepatic malignant melanoma.

The patient in our present case was treated with an extended sequential therapy consisting of surgery, imatinib mesylate, and sunitinib malate. According to the modified NIH consensus criteria in 2008, the patient was at high risk of tumor metastasis[11]. Thus, 400 mg of imatinib mesylate per day was advised as a suitable therapy for at least 3 years after surgery[12,13]. However, the dosage was reduced to 200 mg per day, and the treatment plan was interrupted one year later due to severe side effects of imatinib mesylate. Without blood concentration monitoring data, we cannot be sure whether a high enough dose was given to the patient. When the tumor metastasized after 2 years of continuous administration of imatinib mesylate, sunitinib malate therapy was initiated in accordance with the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology[14].

In conclusion, preoperative diagnosis of primary hepatic GISTs is difficult. Hepatic GISTs must be distinguished from other liver neoplasms or metastatic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract. Primary hepatic GISTs should be considered as highly aggressive. Following complete resection of the tumor, adjuvant therapy with imatinib mesylate for a minimum of 3 years is recommended.

A 67-year-old female complained of fatigue for 6 mo without any abdominal symptoms.

Abdominal physical examination was unremarkable.

The differential diagnosis included hepatic carcinoma, hepatic hemangioma, hepatic cyst and metastases from gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs).

The results of routine blood tests, tumor markers and liver function tests were within normal limits.

An enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a 7.4 cm × 6.2 cm solid-cystic mass in the right hepatic lobe.

Postoperative pathology revealed a mixed-type gastrointestinal stromal tumor that was CD117- and CD34-positive.

The patient was treated with a sequential therapy consisting of surgical excision, imatinib and sunitinib.

Genetic analysis revealed a heterozygous point mutation and deletion in exon 11 of c-KIT.

This case report excluded the diagnosis of metastases from GISTs using CT, ultrasound, esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. Additionally, a genetic analysis was used to confirm the tumor as a primary hepatic GIST.

This case report verified the diagnosis using histological and genetic analyses. Furthermore, the patient underwent an extended sequential therapy consisting of surgery, imatinib mesylate, and sunitinib malate.

P- Reviewer: Peparini N, Palazzo F, Feng F, Sioulas AD, Syam AF S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, Gorstein F, Lasota J, Longley BJ, Miettinen M, O’Leary TJ, Remotti H, Rubin BP. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459-465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2231] [Cited by in RCA: 2149] [Article Influence: 93.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Padhi S, Kongara R, Uppin SG, Uppin MS, Prayaga AK, Challa S, Nagari B, Regulagadda SA. Extragastrointestinal stromal tumor arising in the pancreas: a case report with a review of the literature. JOP. 2010;11:244-248. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Terada T. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the uterus: a case report with genetic analyses of c-kit and PDGFRA genes. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2009;28:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ortiz-Hidalgo C, de Leon Bojorge B, Albores-Saavedra J. Stromal tumor of the gallbladder with phenotype of interstitial cells of Cajal: a previously unrecognized neoplasm. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1420-1423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hu X, Forster J, Damjanov I. Primary malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the liver. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1606-1608. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Huizinga JD, Faussone-Pellegrini MS. About the presence of interstitial cells of Cajal outside the musculature of the gastrointestinal tract. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:468-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum Pathol. 1999;30:1213-1220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 559] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Popescu LM, Hinescu ME, Ionescu N, Ciontea SM, Cretoiu D, Ardelean C. Interstitial cells of Cajal in pancreas. J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:169-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rusu MC, Pop F, Hostiuc S, Curcă GC, Streinu-Cercel A. Extrahepatic and intrahepatic human portal interstitial Cajal cells. Anat Rec (Hoboken). 2011;294:1382-1392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 865] [Article Influence: 50.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dematteo RP, Ballman KV, Antonescu CR, Maki RG, Pisters PW, Demetri GD, Blackstein ME, Blanke CD, von Mehren M, Brennan MF. Adjuvant imatinib mesylate after resection of localised, primary gastrointestinal stromal tumour: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;373:1097-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1075] [Cited by in RCA: 970] [Article Influence: 60.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, Ramadori G, Hohenberger P, Duyster J, Al-Batran SE. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 682] [Article Influence: 52.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Demetri GD, van Oosterom AT, Garrett CR, Blackstein ME, Shah MH, Verweij J, McArthur G, Judson IR, Heinrich MC, Morgan JA. Efficacy and safety of sunitinib in patients with advanced gastrointestinal stromal tumour after failure of imatinib: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1329-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1942] [Cited by in RCA: 1918] [Article Influence: 100.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |