Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2367

Peer-review started: September 9, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: October 30, 2014

Accepted: November 19, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 172 Days and 17.6 Hours

AIM: To study the clinical, endoscopic, sonographic, and cytologic features of ectopic pancreas (EP).

METHODS: This was a retrospective study performed at an academic referral center including two hospitals. Institutional review board approval was obtained. Patients referred to the University Hospital or Denver Health Medical Center Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Lab for gastroduodenal subepithelial lesions (SEL) with a final diagnosis of EP between January 2009 and December 2013 were identified. Patients in this group were selected for the study if they underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or deep biopsy. A review of the medical record was performed specifically to review the following information: presenting symptoms, endoscopic and EUS findings, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging findings, pathology results, procedure-related adverse events, and subsequent treatments after EUS-FNA. EUS with FNA or deep submucosal biopsy was performed in all patients on an outpatient basais by one of two physicians (Attwell A, Fukami N). Review of all subsequent clinic notes and operative reports was performed in order to determine follow-up and final diagnoses.

RESULTS: Between July 2009 and December 2013, 10 patients [3 males, 7 females, median age 52 (26-64) years] underwent EUS for a gastroduodenal SEL and were diagnosed with EP. One patient was symptomatic. Six (60%) lesions were in the antrum, 3 (30%) in the body, and 1 (10%) in the duodenum. A mucosal dimple was noted in 6 (60%). Mean lesion size was 17 (8-25) mm. Gastrointestinal wall involvement: muscularis mucosae, 10%; submucosa, 70%; muscularis propria, 60%; and serosa, 10%. Nine (90%) lesions were hypoechoic and 5 (50%) were homogenous. A duct was seen in 5 (50%). FNA was attempted in 9 (90%) and successful in 8 (80%) patients after 4 (2-6) passes. Cytology showed acini or ducts in 7 of 8 (88%). Superficial biopsies in 7 patients (70%) showed normal gastric mucosa. Deep endoscopic biopsies were taken in 2 patients and diagnostic in one. One patient (10%) developed pancreatitis after EUS-FNA. Two patients (20%) underwent surgery to relieve symptoms or confirm the diagnosis. The main limitation of the study was the fact that it was retrospective and performed at a single medical center.

CONCLUSION: EUS features of EP include antral location, mucosal dimple, location in layers 3-4, and lesional duct, and FNA or biopsy is accurate and effective.

Core tip: Subepithelial lesions (SEL) of the upper gastrointestinal (GI) tract are common incidental findings during GI endoscopy. Ectopic pancreas (EP) is an uncommon yet innocent SEL that should be differentiated from premalignant lesions such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors or neuroendocrine tumors. Noninvasive studies such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or standard mucosal biopsies cannot reliably diagnose EP, so the role of endoscopic ultrasound-fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) was studied. Herein the endoscopic, endosonographic, cytologic, and histologic features of EP are presented along with a summary of the pertinent, existing literature. Our data support the conclusion that EUS-FNA is a safe and effective diagnostic tool for EP.

- Citation: Attwell A, Sams S, Fukami N. Diagnosis of ectopic pancreas by endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2367-2373

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2367

Ectopic pancreas (EP), also known as pancreatic rest or aberrant pancreas, is defined as pancreatic tissue residing outside the normal pancreas and containing its own duct and vascular supply. EP has a world prevalence of 1%-13% but is infrequently diagnosed because the vast majority of cases are asymptomatic. Most cases are found incidentally during endoscopy, surgery or autopsy[1]. The classic presentation to gastroenterologists is an incidental, small, < 2 cm, subepithelial lesion (SEL) in the gastric antrum seen during esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) in a middle-aged patient. Other lesions can have a similar appearance and presentation, including gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), which have a small but real risk of malignant transformation. EP, on the other hand, does not require treatment unless symptomatic, and can almost always be dismissed in the absence of symptoms. Hence, confirming the diagnosis of EP would be helpful to stratify patients for surgical resection.

Cross sectional imaging and EGD with standard forceps biopsies do not diagnose most EP lesions, and more aggressive maneuvers such as snare resection, tunneling deep biopsies, or surgical resection carry appreciable risks. Thus, sensitive yet safe and accurate diagnostic tests for EP are desired. EUS can effectively characterize SELs and determine the organ or layer of origin, resectability, and lymph node status[2]. EUS has been used to evaluate EP in several studies, and the sonographic features can differentiate EP from other SELs[2-10]. However, the available literature on EUS with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) for EP is small and essentially limited to case reports from Asia[11-13]. Herein we describe our experience with EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of EP at a large, tertiary referral center in the United States. Our objective is to review the clinical, endoscopic, sonographic, and cytologic features of EP and to describe any treatments undertaken.

This was a retrospective study based on chart review. A search was made through the hospital’s Pathology records and endoscopy database (Provation, Minneapolis, MN) for patients with a diagnosis of EP based on fine-needle aspirate, endoscopic biopsy, or surgical excision. Patients found to have incidental EP during surgery were excluded. All patients who underwent EUS+/- FNA and who were ultimately diagnosed with EP based on pathology were included in the analysis. The Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board reviewed and approved the study.

Presenting symptoms, endoscopic and EUS findings, pathology results, complications, and subsequent treatments were retrieved from the electronic medical record. Follow-up was obtained by chart review. In cases where symptoms or procedural complications were questionable, the patient was contacted directly by telephone or seen in clinic.

Patients were directly referred for EUS from an outside institution or the hospitals’ GI clinics. EUS was performed on an outpatient basis at the University of Colorado Hospital or Denver Health Medical Center by one of 2 dedicated endoscopists (Attwell A, Fukami N) with patients in the left lateral decubitus position. Patients were given moderate sedation using intravenous midazolam and fentanyl or monitored anesthesia care using intravenous propofol, depending on the patient’s characteristics. EGD with a standard gastroscope was performed initially. Standard mucosal biopsies were typically not performed at the time of EUS. A curvilinear array or radial echoendoscope (Olympus America, Melville, NY or Pentax Medical Co., Montvale, NJ) or 20 mHz ultrasound probe (Olympus) though the gastroscope was used to survey the lesion and the surrounding structures. The size, appearance, and extent of the lesion was assessed and documented.

FNA was performed using a 19- or 22-gauge needle through the linear scope under endosonographic guidance. An on-site cytopathologist was available in all cases and reviewed the aspirate on a slide. In select cases where FNA was technically challenging due to the location or the aspirate showed pauci-cellular specimen, a deep tunneling-type biopsy was performed using jumbo-capacity forceps approximately 5-8 mm into the lesion depending on its size.

Between July 2009 and April 2014, 10 patients underwent EUS for further evaluation of gastroduodenal SELs and were ultimately diagnosed with EP. The median age was 52 (26-64) years and 7 were females. Median follow-up was 21 mo (range, 8-60 mo).

One patient presented with recurrent epigastric pain and presumed ectopic pancreatitis; all others were asymptomatic. In asymptomatic patients, EP was diagnosed during EGD performed for unrelated indications such as chronic gastroesophageal reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, or suspected GI bleeding. Three (30%) lesions were visible on contrast computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen. All patients had previously undergone EGD revealing a SEL. Superficial mucosal biopsies had been performed in 7 patients (70%) and were non-diagnostic in all cases.

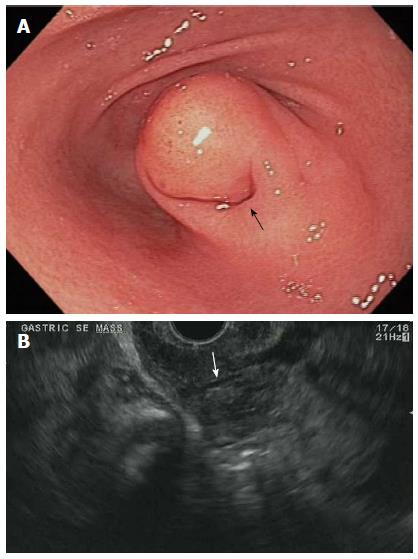

The endoscopic and endosonographic findings are summarized in Table 1. EGD immediately before EUS revealed a single SEL in each patient. Six (60%) were located in the antrum, 3 (30%) in the body, and 1 (10%) in the duodenal bulb. An overlying mucosal dimple was noted in 6 (60%) patients (Figure 1A).

| n | Size | Location | Mucosal dimple | GI layer | EUS appearance | Duct seen | FNA success | FNA accuracy |

| 10 | 17 mm (8-25 mm) | Body/antrum (90%) | Yes (60%) | Submucosa (70%) | Hypoechoic (90%) | Yes (50%) | 80% | 88% |

EUS was performed with a curvilinear array (n = 10), radial (n = 7), or probe (n = 1) echoendoscope. By EUS, the mean lesion size was 17 (8-25) mm. The GI wall layer involvement was as follows: 7 lesions (70%) involved the submucosa; 6 lesions (60%) involved the muscularis propria; 1 lesion (10%) involved the muscularis mucosae; 1 lesion (10%) involved the subserosa. Five lesions (50%) involved more than 1 layer. Nine (90%) lesions were hypoechoic and 1 (10%) was isoechoic. Five lesions (50%) were homogenous and 5 (50%) were heterogenous, independent of the presence of a ductal stricture, which was seen in 5 lesions (50%) (Figure 1B).

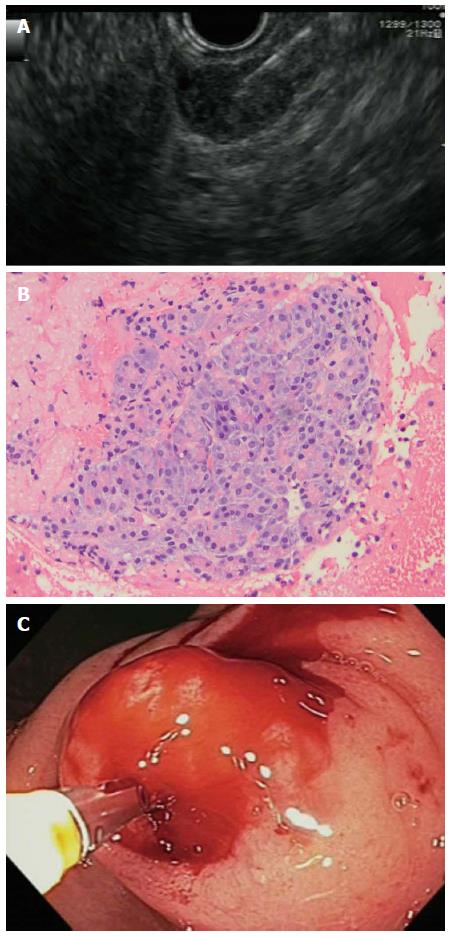

FNA was attempted in 9 (90%) with a 22G (n = 6) or 19G (n = 1) needle or both (n = 2), or with a (19G) core biopsy needle (n = 1) (Figure 2A). FNA was deferred in one case in favor of deep, direct biopsy. Aspiration of cellular material was successful in 8 (89%) of the 9 patients after a mean 4 (2-6) passes. Cytology showed acini in 7 of the 8 (88%) patients with adequate cytology (Figure 2B) and occasionally ductal structures (n = 3). In one non-diagnostic case, FNA showed only acute inflammatory cells. Acute ectopic pancreatitis was diagnosed in 2 patients based on labs, imaging, and EGD findings.

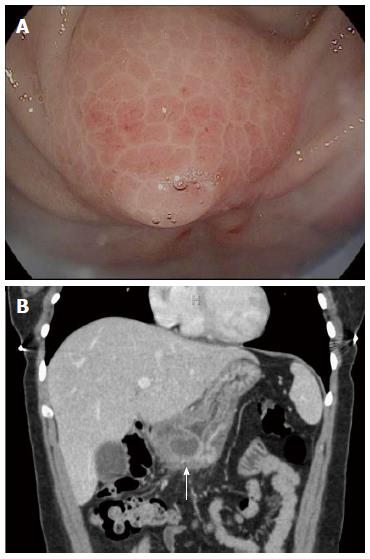

Deep, tunneling biopsies were taken after EUS in 2 patients (Figure 2C), in 1 case because of a pauci-cellular FNA aspirate and in the other case when FNA was deferred because of the small size and difficult location of the SEL. Deep biopsy was diagnostic in 1 of these 2 cases. One case was diagnosed only after surgical resection. This was a 26-year-old female with recurrent epigastric pain over 3 mo. CT showed a 2 cm mass in the antrum with surrounding inflammatory changes (Figure 3B), and EGD showed a SEL with edema and erythema (Figure 3A), both suggestive of acute ectopic pancreatitis. She underwent definitive wedge resection of the mass after resolution of the pancreatitis. Final pathology of EP was confirmed for each patient. Asymptomatic patients were reassured and no further imaging studies were planned.

One patient (10%) developed mild acute ectopic pancreatitis after EUS-FNA. This was a 30-year-old female with metastatic neuroendocrine tumor and an incidental SEL in the stomach detected with staging CT scan. She developed epigastric pain, elevated serum lipase, and radiographic evidence of ectopic pancreatitis 24 h after EUS-FNA. She was treated supportively and eventually underwent wedge resection of the EP at the time of surgery for her neuroendocrine tumors. One other patient underwent wedge resection of EP to relieve symptoms and to make a definitive diagnosis, as described above. Her surgery was uneventful and the epigastric pain resolved after surgery. No other adverse events occurred during this study.

First described in the ileum in 1727, EP now carries a prevalence of 1%-13% by autopsy and 0.5% by laparotomy[14,15]. Its pathogenesis presumably relates to faulty migration of the ventral or dorsal pancreatic buds during the foregut rotation of embryogenesis[16]. The stomach is the most common site, followed by duodenum, jejunum, ileum, and peritoneum.

The incidence of SELs may be increasing because of improvement and liberal use of noninvasive imaging, endoscopy, and EUS[17]. In one study, the incidence of SELs was 0.36% in 15104 patients undergoing routine EGD[18]. Approximately 5%-9% of submucosal gastrointestinal lesions evaluated by EUS may be attributed to EP[2,10].

The diagnosis of intraluminal EP can be challenging, but it is important. When EP can be differentiated from a GIST or neuroendocrine tumor, aggressive maneuvers such as unroofing, biopsy, endoscopic resection, or surgery can be avoided in the asymptomatic patient. Noninvasive imaging studies such as CT and magnetic resonance imaging may show nonspecific enhancing thickening in the stomach or bowel, but many lesions are missed[19]. Endoscopy typically reveals a SEL with bland, normal overlying mucosa. The greater curve of the gastric antrum is the most common location, followed by gastric body, duodenal bulb, fundus, descending duodenum, and cardia[20]. A central umbilication, which is attributed to a duct orifice, is seen over the lesion in 35%-90% of cases[7,9]. Because of the subepithelial nature of the EP, conventional biopsies are only helpful in 10% of cases[7].

Though relatively invasive, EUS is suited for assessing SELs and is more accurate than EGD alone[2]. In numerous studies it has proven to be safe and effective for examining EPs and defining its characteristic features[2-10]. Sonographically, EP is typically hypoechoic and arises from the submucosa (3rd layer), but approximately 17% and 10% may involve the muscularis propria and serosa, respectively[21]. Nonspecific thickening of the muscularis around the lesion may also occur. In over half of cases, an anechoic ductal structure is seen within the lesion[9].

Pathologic confirmation of EP requires deep forceps biopsy, EUS with FNA or core biopsy, or surgical biopsy. In one study of SE masses that included 10 patients with EP, the accuracy of EUS criteria alone for making a diagnosis was only 50%[3]. Previous case reports suggest that EUS-FNA can diagnose EP accurately and safely during the first attempt[9,12-13,22].

In our study, which is the largest American series of EP patients undergoing EUS, the location, endoscopic appearance, and sonographic features of the lesions were typical for EPs described in other studies. EPs were predominantly hypoechoic, homogenous, and arising from the submucosa (3rd) layer in the gastric body or antrum. An intra-lesional duct structure, overlying mucosal dimple, or both was present in approximately half of the cases. EUS-FNA confirmed the diagnosis in 7 patients with a cellular aspirate, including one case using a core biopsy needle. In these 7 patients, cytologic analysis showed acinar structures, and ductal epithelium was also seen in 3 of the 7 cases. Islet cells were not seen cytologically, an expected finding since EP typically only contain acini and ducts[23]. In 2 cases, a deep tunneling-type biopsy was performed, and in one case the diagnosis was confirmed after surgical resection. Thus, EUS with various endoscopic methods eventually led to the diagnosis in 90% of patients with EP at our institution. Moreover, patients could be discharged without additional surveillance.

One could argue that the diagnosis of EP can be made based on endoscopic and sonographic criteria alone in some cases, for example a classic hypoechoic lesion in the antrum with mucosal dimple and visible duct on EUS. However other SELs including GISTs may contain hypoechoic spaces, and since the diagnostic accuracy of EUS or imaging alone is undefined, we feel that FNA or deep biopsy should be performed whenever possible.

A core needle biopsy was successful in one of our cases, but this practice has not been well established in SELs due to size and location, and the tissue yield has not been shown to exceed that of FNA in EP. In a series of 65 patients with SELs, which included predominantly smooth muscle tumors but also 5 cases of EP, this technique led to a diagnosis in 18 of 65 patients (28%) but technical failure occurred in 43%[24]. Given the small size of most EP lesions and the added stiffness of core biopsy needles, we would not recommend this practice routinely.

In order to obtain sufficient tissue, various endoscopic “unroofing” techniques for SELs have also been described with large forceps, snare, or needle-knife[25,26]. Alternatively, SELs may be completely or partially resected with or without the use of saline injection, banding, or detachable loop beneath the lesion[27-29]. The diagnostic accuracy exceeds 90% and lesions including EPs can be entirely removed with these methods. However, immediate bleeding requiring hospitalization or endotherapy may occur in 11%-56% of cases[26,27] and chest or abdominal pain in 2%-12%[27,29]. Unlike other SELs, the benign nature of EP should not warrant the risks of such an aggressive approach. The accuracy of FNA in our study (7 of 9, 78%) was less than ideal, but it was similar to that of GISTs from other studies[30]. Other modes of tissue acquisition should be considered when EUS-FNA is non-diagnostic. We favor initial evaluation with EUS-FNA, then proceeding with a deep, tunneling-type (unroofing) forceps biopsy when FNA is technically difficult or non-diagnostic.

One patient in our cohort presented with acute ectopic pancreatitis (AEP) and another developed pancreatitis following EUS-FNA, and both underwent resection. The latter was recently published as the first such case reported in the literature[22]. Excluding these cases, the low incidence of complicated EP in our cohort (20%) is consistent with the existing literature, where most patients with EP are asymptomatic. Approximately 100 cases of EP-related adverse events have been published including AEP, pseudocyst, a palpable abdominal mass, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gastric outlet obstruction, and adenocarcinoma[14,23,31-38]. For such cases, resection is advocated to relieve and/or prevent symptoms, or when the diagnosis is uncertain. Malignancy within EP has been reported and was even found to develop in 12.7% of cases in 1 surgical series[20,35-36,39]. However, the overall risk of cancer in incidental EP is estimated to be very small and does not warrant prophylactic resection. Resection typically involves a surgical approach, but endoscopic mucosal resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection for EP have also been described[40,41].

We recognize some limitations in this study. Due to its retrospective nature, patients with a SEL and non-diagnostic EUS-FNA who were subsequently observed may have been missed. However, because we generally investigate SELs until a diagnosis is established or patient declines further testing, this effect should be minimal. Similarly, post-procedure complications or symptoms could be missed in patients who returned to their referring institution. However, any patients contacted or seen by the referring physician in this study were asked specifically about complications. Finally, EUS is highly subjective and FNA of EP may be difficult because of their small size or location along the greater curve; thus, the study’s findings may be less applicable to centers with lower volume or experience.

In conclusion, EP is typically an incidental and benign entity, but confirming the diagnosis with EUS-FNA is appropriate, safe, and effective. Common endoscopic and sonographic features of EP include a location in the gastric antrum, a mucosal umbilication, involvement of GI wall layers 3 or 4, and the presence of an intra-lesional duct. FNA confirms the diagnosis and subsequently allows for safe observation in the vast majority of patients. Acute ectopic pancreatitis is rare but should be noted as a potential complication of EUS-FNA.

Subepithelial lesions (SELs) in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are being diagnosed with increasing frequency because of the liberal use and improved quality in radiologic studies and endoscopy. Though relatively uncommon, ectopic pancreas (EP) is an innocent type of SEL that should be differentiated from other, premalignant SELs in order to maximize treatment efficacy and avoid harm. SELs are not well-visualized on most radiologic studies, and routine endoscopic (mucosal) biopsies do not typically detect SELs. Thus, better diagnostic studies for SELs and EP in particular are needed.

SELs are frequently detected during GI endoscopy procedures, but differentiating the various types of SELs remains problematic. Various diagnostic techniques currently being used for SELs include endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), EUS with fine-needle aspiration (EUS-FNA), deep endoscopic biopsy, partial or complete endoscopic snare excision, or surgical resection. These techniques allow physicians to differentiate the various types of SELs and, in some cases, to remove lesions at the same time. However, only a small subset of SELs carry malignant potential and thus require resection, so differentiating fully benign lesions such as EP with high accuracy is important, as it may prevent unnecessary treatments or complications.

The specific role of EUS-FNA or EUS with deep biopsy in diagnosing EP has not been well-studied. The available literature to date has been limited to case reports and small case series in Asia. Our study is new and different in that it addresses the role of EUS-FNA or EUS with deep biopsy specifically for EP, it is the largest such case series to date. It is also the only such American series.

This study will help physicians recognize the various endoscopic features of EP, which are encountered not infrequently in clinical practice. It will also help gastroenterologists, particularly those who practice endoscopic ultrasound, become familiar with the endosonographic and cytologic features specific to EP. The study should also help endosonographers become more comfortable with the technical aspects of EUS-FNA or deep biopsy for EP, while also recognizing that EUS-FNA can potentially trigger acute pancreatitis. Collectively, gastroenterologists can use this study to differentiate EP from other SELs and thereby avoid unnecessary surgical or endoscopic resection procedures.

EP is pancreatic tissue that develops and resides outside the primary pancreas organ, most commonly in the stomach. EUS is an endoscopic procedure whereby a lighted camera tube (endoscope) containing an ultrasound probe is inserted through the mouth and into the GI tract, where it is used to take images of the GI lumen and surrounding organs. Endoscopic ultrasound may be used to guide a needle into selected organs, where cells can be aspirated and sent to Cytology for review. This is called endoscopic-guided ultrasound or EUS-FNA. A SEL in the GI tract is a mass or other lesion that arises from beneath the surface epithelial layer of the gut. A GIST is a type of SEL of mesenchymal origin with malignant potential that most commonly occurs in the stomach.

This is a small but strong retrospective study evaluating the role of EUS-FNA or deep biopsy in the diagnosis of EP lesions. The authors nicely summarize the endoscopic, sonographic, cytologic, and histologic features of EP lesions in 10 patients encountered in routine clinical practice at 2 institutions in an academic tertiary referral center.

P- Reviewer: Ahluwalia NK, Larentzakis A S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Trifan A, Târcoveanu E, Danciu M, Huţanaşu C, Cojocariu C, Stanciu C. Gastric heterotopic pancreas: an unusual case and review of the literature. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012;21:209-212. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Rösch T, Kapfer B, Will U, Baronius W, Strobel M, Lorenz R, Ulm K. Accuracy of endoscopic ultrasonography in upper gastrointestinal submucosal lesions: a prospective multicenter study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37:856-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Karaca C, Turner BG, Cizginer S, Forcione D, Brugge W. Accuracy of EUS in the evaluation of small gastric subepithelial lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:722-727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Okazaki K, Takakuwa H. Gastric aberrant pancreas: EUS analysis in comparison with the histology. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:493-497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Changchien CS, Hsiaw CM, Hu TH. Endoscopic ultrasonographic classification of gastric aberrant pancreas. Chang Gung Med J. 2000;23:600-607. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kim JH, Lim JS, Lee YC, Hyung WJ, Lee JH, Kim MJ, Chung JB. Endosonographic features of gastric ectopic pancreases distinguishable from mesenchymal tumors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e301-e307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen SH, Huang WH, Feng CL, Chou JW, Hsu CH, Peng CY, Yang MD. Clinical analysis of ectopic pancreas with endoscopic ultrasonography: an experience in a medical center. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:877-881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Watanabe K, Irisawa A, Hikichi T, Takagi T, Shibukawa G, Sato M, Obara K, Ohira H. Acute inflammation occurring in gastric aberrant pancreas followed up by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4:331-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Park SH, Kim GH, Park do Y, Shin NR, Cheong JH, Moon JY, Lee BE, Song GA, Seo HI, Jeon TY. Endosonographic findings of gastric ectopic pancreas: a single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1441-1446. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Yasuda K, Nakajima M, Yoshida S, Kiyota K, Kawai K. The diagnosis of submucosal tumors of the stomach by endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:10-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jang KY, Park HS, Moon WS, Kim CY, Kim SH. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach diagnosed by endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology. Cytopathology. 2010;21:418-420. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Goto J, Ohashi S, Okamura S, Urano F, Hosoi T, Ishikawa H, Segawa K, Hirooka Y, Ohmiya N, Itoh A. Heterotopic pancreas in the esophagus diagnosed by EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:812-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fujii M, Kawamoto H, Nagahara T, Tsutsumi K, Kato H, Shinoura S, Seno S, Okada H, Yamamoto K. A case of gastric aberrant pancreas diagnosed with EUS-guided FNA. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:407-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rimal D, Thapa SR, Munasinghe N, Chitre VV. Symptomatic gastric heterotopic pancreas: clinical presentation and review of the literature. Int J Surg. 2008;6:e52-e54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gokhale UA, Nanda A, Pillai R, Al-Layla D. Heterotopic pancreas in the stomach: a case report and a brief review of the literature. JOP. 2010;11:255-257. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Armstrong CP, King PM, Dixon JM, Macleod IB. The clinical significance of heterotopic pancreas in the gastrointestinal tract. Br J Surg. 1981;68:384-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Wang D, Wei XE, Yan L, Zhang YZ, Li WB. Enhanced CT and CT virtual endoscopy in diagnosis of heterotopic pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3850-3855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hedenbro JL, Ekelund M, Wetterberg P. Endoscopic diagnosis of submucosal gastric lesions. The results after routine endoscopy. Surg Endosc. 1991;5:20-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Catalano MF. Endoscopic ultrasonography for esophageal and gastric mass lesions. Gastroenterologist. 1997;5:3-9. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Hickman DM, Frey CF, Carson JW. Adenocarcinoma arising in gastric heterotopic pancreas. West J Med. 1981;135:57-62. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Barrocas A, Fontenelle LJ, Williams MJ. Gastric heterotopic pancreas: a case report and review of literature. Am Surg. 1973;39:361-365. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Attwell A, Sams S, Fukami N. Induction of acute ectopic pancreatitis by endoscopic ultrasound with fine-needle aspiration. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1196-1198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Haj M, Shiller M, Loberant N, Cohen I, Kerner H. Obstructing gastric heterotopic pancreas: case report and literature review. Clin Imaging. 2002;26:267-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee JH, Choi KD, Kim MY, Choi KS, Kim do H, Park YS, Kim KC, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jung HY. Clinical impact of EUS-guided Trucut biopsy results on decision making for patients with gastric subepithelial tumors ≥ 2 cm in diameter. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1010-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | de la Serna-Higuera C, Pérez-Miranda M, Díez-Redondo P, Gil-Simón P, Herranz T, Pérez-Martín E, Ochoa C, Caro-Patón A. EUS-guided single-incision needle-knife biopsy: description and results of a new method for tissue sampling of subepithelial GI tumors (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:672-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lee CK, Chung IK, Lee SH, Lee SH, Lee TH, Park SH, Kim HS, Kim SJ, Cho HD. Endoscopic partial resection with the unroofing technique for reliable tissue diagnosis of upper GI subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria on EUS (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:188-194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hunt GC, Smith PP, Faigel DO. Yield of tissue sampling for submucosal lesions evaluated by EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;57:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cantor MJ, Davila RE, Faigel DO. Yield of tissue sampling for subepithelial lesions evaluated by EUS: a comparison between forceps biopsies and endoscopic submucosal resection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Binmoeller KF, Shah JN, Bhat YM, Kane SD. Suck-ligate-unroof-biopsy by using a detachable 20-mm loop for the diagnosis and therapy of small subepithelial tumors (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:750-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sepe PS, Moparty B, Pitman MB, Saltzman JR, Brugge WR. EUS-guided FNA for the diagnosis of GI stromal cell tumors: sensitivity and cytologic yield. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shaib YH, Rabaa E, Feddersen RM, Jamal MM, Qaseem T. Gastric outlet obstruction secondary to heterotopic pancreas in the antrum: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:527-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Covarelli P, Cirocchi R, Bellochi R, Ricci P, Morozzi B, Nonno S, Mosci F. [Upper digestive hemorrhage as a rare manifestation of ectopic pancreas with gastric localization]. G Chir. 1997;18:97-100. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Mulholland KC, Wallace WD, Epanomeritakis E, Hall SR. Pseudocyst formation in gastric ectopic pancreas. JOP. 2004;5:498-501. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Chung JP, Lee SI, Kim KW, Chi HS, Jeong HJ, Moon YM, Kang JK, Park IS. Duodenal ectopic pancreas complicated by chronic pancreatitis and pseudocyst formation--a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 1994;9:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bini R, Voghera P, Tapparo A, Nunziata R, Demarchi A, Capocefalo M, Leli R. Malignant transformation of ectopic pancreatic cells in the duodenal wall. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1293-1295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Emerson L, Layfield LJ, Rohr LR, Dayton MT. Adenocarcinoma arising in association with gastric heterotopic pancreas: A case report and review of the literature. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:53-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lee JC, Wong KP, Lo SS, Cheng CS, Lau KY. Acute ectopic pancreatitis. Hong Kong Med J. 2008;14:501-502. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Caberwal D, Kogan SJ, Levitt SB. Ectopic pancreas presenting as an umbilical mass. J Pediatr Surg. 1977;12:593-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Nakao T, Yanoh K, Itoh A. Aberrant pancreas in Japan. Review of the literature and report of 12 surgical cases. Med J Osaka Univ. 1980;30:57-63. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Khashab MA, Cummings OW, DeWitt JM. Ligation-assisted endoscopic mucosal resection of gastric heterotopic pancreas. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2805-2808. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ryu DY, Kim GH, Park do Y, Lee BE, Cheong JH, Kim DU, Woo HY, Heo J, Song GA. Endoscopic removal of gastric ectopic pancreas: an initial experience with endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4589-4593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |