Published online Feb 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1872

Peer-review started: May 23, 2014

First decision: June 27, 2014

Revised: July 28, 2014

Accepted: September 12, 2014

Article in press: September 16, 2014

Published online: February 14, 2015

Processing time: 264 Days and 20.8 Hours

AIM: To introduce an air insufflation procedure and to investigate the effectiveness of air insufflation in preventing pancreatic fistula (PF).

METHODS: From March 2010 to August 2013, a total of 185 patients underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) at our institution, and 74 patients were not involved in this study for various reasons. The clinical outcomes of 111 patients were retrospectively analyzed. The air insufflation test was performed in 46 patients to investigate the efficacy of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis during surgery, and 65 patients who did not receive the air insufflation test served as controls. Preoperative assessments and intraoperative outcomes were compared between the 2 groups. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for PF.

RESULTS: The two patient groups had similar baseline demographics, preoperative assessments, operative factors, pancreatic factors and pathological results. The overall mortality, morbidity, and PF rates were 1.8%, 48.6%, and 26.1%, respectively. No significant differences were observed in either morbidity or mortality between the two groups. The rate of clinical PF (grade B and grade C PF) was significantly lower in the air insufflation test group, compared with the non-air insufflation test group (6.5% vs 23.1%, P = 0.02). Univariate analysis identified the following parameters as risk factors related to clinical PF: estimated blood loss; pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm; invagination anastomosis technique; and not undergoing air insufflation test. By further analyzing these variables with multivariate logistic regression, estimated blood loss, pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm and not undergoing air insufflation test were demonstrated to be independent risk factors.

CONCLUSION: Performing an air insufflation test could significantly reduce the occurrence of clinical PF after PD. Not performing an air insufflation test was an independent risk factor for clinical PF.

Core tip: The present study introduces the application of the air insufflation test for the prevention of pancreatic fistula (PF) and investigates its effectiveness. This clinical study confirms that the air insufflation test can significantly reduce the occurrence of clinical PF. In addition, estimated blood loss, pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm and not performing an air insufflation test are independent risk factors for clinical PF.

- Citation: Yang H, Lu XF, Xu YF, Liu HD, Guo S, Liu Y, Chen YX. Application of air insufflation to prevent clinical pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(6): 1872-1879

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i6/1872.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1872

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) is the standard operation for the resection of periampullary diseases. In recent years, the mortality rate has decreased dramatically to less than 5% in high-volume centers due to improved intraoperative management and better postoperative care. Unfortunately, there has not been a similar reduction in the pancreatic fistula (PF) rate, which has remained at approximately 30%[1-3].

Pancreatic leakage has been the primary factor linked with death in some case studies[4]. Various risk factors related to PF have been identified, such as a main pancreatic duct diameter of 3 mm or less[2,5-8], soft pancreatic parenchyma[7,9-12] and intraoperative blood loss[2,11-13]. Other risk factors, such as heart disease[9,14], age[6], male sex[11], cirrhotic liver and body mass index[7], have also been reported. In addition, to prevent PF, numerous strategies have been applied in previous literatures. Intraoperative techniques, such as modified reconstruction with pancreaticogastrostomy[15], pancreatic duct ligation[16], the use of omentum or the falciform ligament[17,18] and obliteration of the pancreatic duct with glue[19], have been performed. Postoperative management, including the use of somatostatin analogs, has also been reported. However, none of these strategies has investigated pancreatic leakage during surgery. Furthermore, most of these strategies have been controversial[20-23] and have not been routinely used in most hospital centers. More effective and confirmative surgical techniques are needed to prevent PF.

The present study introduced the air insufflation test, a simple and effective technique, for the prevention of PF. The detailed process of performing an air insufflation test during surgery and its efficacy in preventing PF are presented.

PD was performed in 185 consecutive patients between March 2010 and August 2013 at the Qilu Hospital of Shandong University in China. The exclusion criteria applied to: patients undergoing emergency PD for trauma; patients with ongoing acute pancreatitis at the time of surgery; and operations performed by surgeons without a professional title. A total of 111 patients were enrolled in this study, and these patients were divided into 2 groups according to whether they received the air insufflation test during surgery or not. In total, 46 patients [the air insufflation test (AIT) group] received the air insufflation test during surgery, and 65 patients (controls) did not receive the air insufflation test during surgery.

Preoperative demographics and clinical information of the patients were retrospectively obtained from the patients’ medical records (Table 1). Preoperative biliary drainage was the main preoperative invasive treatment. For patients with a total bilirubin level greater than 170 μmol/L or with poor general health conditions, preoperative biliary drainage was performed.

| AIT group(n = 46) | Non-AIT group(n = 65) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 55.3 ± 11.5 | 58.1 ± 7.8 | 0.15 |

| Gender | 0.64 | ||

| Male | 24 | 31 | |

| Female | 22 | 34 | |

| Main presenting symptom | |||

| Jaundice | 25 | 35 | 0.96 |

| Abdominal pain | 10 | 24 | 0.09 |

| Cholangitis | 3 | 8 | 0.50 |

| ASA | 0.64 | ||

| II | 41 | 56 | |

| III | 5 | 9 | |

| Preoperative ALT | 226.0 ± 204.2 | 193.6 ± 205.0 | 0.41 |

| Preoperative AST | 150.2 ± 152.1 | 138.3 ± 150.7 | 0.68 |

| Preoperative bilirubin (μmol/L) | 189.0 ± 171.9 | 137.11 ± 131.8 | 0.08 |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L) | 66.2 ± 8.5 | 65.8 ± 7.8 | 0.81 |

| Presence of comorbid illness | 23 | 27 | 0.38 |

| Mellitus diabetes | 8 | 4 | 0.06 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 2 | 4 | 0.68 |

| Artery hypertension | 9 | 13 | 0.96 |

| Coronaropathy | 4 | 6 | 1.00 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 0.60 | ||

| Yes | 21 | 33 | |

| No | 25 | 32 | |

| Smoking | 13 | 14 | 0.42 |

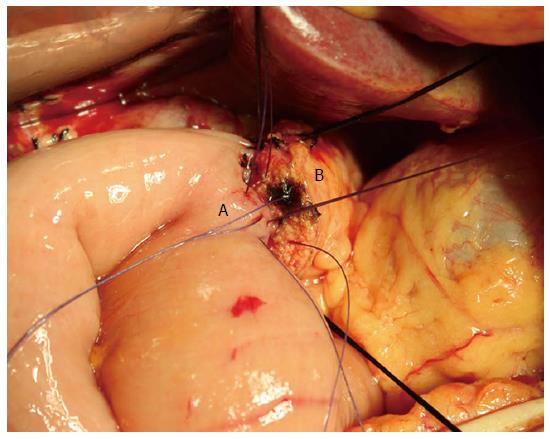

The operations were performed by surgeons with professional titles specializing in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery. Conventional or pylorus-preserving PD was performed according to the decision of the individual surgeon. Segmental resection of the portal vessels or superior mesenteric vessels was performed if a pancreatic head mass was inseparable from the vessels. To reestablish gastrointestinal continuity, a two-layer end to side pancreatic duct to jejunal mucosa anastomosis (duct to mucosa) or a two-layer end to side invagination anastomosis was performed (Figure 1). After pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, an end to side hepaticojejunostomy and an antecolic gastrojejunostomy or duodenojejunostomy were performed, using the same jejunal loop. Depending on the diameter of the pancreatic duct, a Fr 4 to 10 polyvinyl catheter with multiple perforations was inserted into the pancreatic duct.

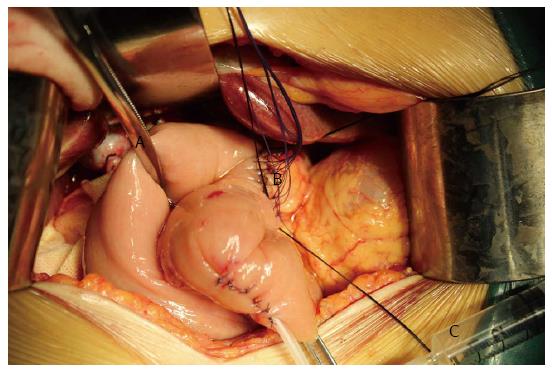

To investigate the efficacy of the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis, the air insufflation test (Figure 2) was performed in the AIT group. An intestinal clamp was used to close the distal intestinal loop approximately 6 cm from the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. Then, the anastomosis was submerged in irrigation fluid, and air was injected gently with a 1 or 5 mL syringe through the pancreatic duct stent to determine whether there were bubbles generated in the irrigation fluid. It must be noted that air should be gently injected into the jejunal stump to prevent the pressure in the jejunal lumen from ascending too rapidly. In addition, the pressure in the jejunal stump should be sufficiently moderate to generate bubbles but not damage the anastomosis. In clinical practice, we regarded the pressure as moderate when the tension of the jejunal wall was the same as that of normal liver tissue or the oral labia. If bubbles were present during the test, the anastomosis where the bubbles were generated was sutured. Then, the anastomosis was tested again until no bubbles were found. If the leakage could not be resolved, re-anastomosis was performed. Prophylactic drains were routinely placed posterior to the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis and the hepaticojejunal anastomosis. Fibrin glue was not used in any of the patients.

Prophylactic antibiotics and somatostatin or octreotide were administered to all of the patients for 72 h postoperatively and during the first postoperative week, respectively. The nasogastric tube was removed when bowel sounds returned. An oral diet was initiated 5 to 7 d after surgery, depending on the patient’s condition. The volume and characteristics of the drainage fluid were monitored every day. Amylase levels were measured on postoperative days 1, 3, 5, and 7 and when the characteristics of the drainage fluid changed, or abdominal symptoms occurred. If there was no evidence of PF, the pancreatic duct drainage catheter was locked 10 d after surgery and removed 48 h later if no abnormalities occurred. If a PF occurred, the catheter was placed in situ until the leakage was resolved.

The primary end point was PF. The secondary end points were mortality and morbidity, including delayed gastric emptying (DGE), intra-abdominal hemorrhage, bile fistula, intra-abdominal infection, intra-abdominal collection, and heart failure.

Mortality and morbidity were defined as death or complications, respectively, occurring within 30 d of surgery. PF was defined as drainage of any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase content greater than 3 times the serum amylase activity. The three different grades of PF (grades A-C) were defined according to the clinical impact on the patient’s hospital course[24]. Grade B and grade C PF were regarded as clinical PF. DGE represented the inability to return to a standard diet by the end of the first postoperative week and included prolonged nasogastric intubation of the patient[25]. Postoperative hemorrhage was defined in accordance with the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery guidelines, based on the time of onset (early or late hemorrhage), the location (intraluminal or extraluminal), and the severity (mild or severe)[26].

The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous data are expressed as mean ± SD. The comparison of continuous or categorical variables was performed with Student’s t-test or the χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test), respectively. Significant variables from the univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate stepwise logistic regression analysis. A P value ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

The baseline demographics of the 111 patients included in the present study are shown in Table 1. These results suggested that the two groups were well matched for age, sex, main presenting symptom, American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status score, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate transaminase, preoperative bilirubin, preoperative albumin, presence of comorbid illness, preoperative biliary drainage and smoking status (Table 1).

The intraoperative data and pathological diagnoses are listed in Table 2. The two groups were similar in terms of operative factors, pancreatic factors and pathological diagnoses. Most of the operations (96/111, 86.5%) were performed for malignant diseases.

| AIT group(n = 46) | Non-AIT group(n = 65) | P value | |

| Operative factors | |||

| Combined vascular resection cases | 1 | 2 | 1.00 |

| Duration of operation (min) | 372.9 ± 106.5 | 344.7 ± 86.4 | 0.13 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 347.3 ± 195.7 | 289.7 ± 159.9 | 0.09 |

| Blood transfusion cases | 13 | 20 | 0.78 |

| Pancreatic factors | |||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 0.76 | ||

| ≤ 3 mm | 31 | 42 | |

| > 3 mm | 15 | 23 | |

| Pancreatic texture | 0.58 | ||

| Soft | 34 | 51 | |

| Hard | 12 | 14 | |

| Pancreatic anastomosis technique | 0.17 | ||

| Duct to mucosa anastomosis | 20 | 20 | |

| End to side invagination anastomosis | 26 | 45 | |

| Pathological diagnoses | 0.66 | ||

| Malignant disease | 39 | 57 | |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 11 | 17 | 0.79 |

| Ampullar carcinoma | 10 | 12 | 0.67 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 8 | 12 | 0.89 |

| Duodenal carcinoma | 10 | 16 | 0.72 |

| Benign diseases | 7 | 8 |

The AIT was successfully performed in all 46 of the patients in the AIT group. Pancreatic leakage was found in 10 patients, and immediate repair or re-anastomosis was performed.

The overall mortality, morbidity, and PF rates of all of the patients were 1.8%, 48.6%, and 26.1%, respectively. No significant differences were found in the mortality rate (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 2.2% vs 1.5%, P = 1.00) or the overall complication rate (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 43.5% vs 52.3%, P = 0.36) between the two groups (Table 3).

| AIT group(n = 46) | Non-AIT group(n = 65) | P value | |

| Hospital mortality | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Morbidity | 20 | 34 | 0.36 |

| Pancreatic fistula | 9 | 20 | 0.19 |

| Grade A | 6 | 5 | 0.54 |

| Grade B | 2 | 8 | 0.02 |

| Grade C | 1 | 7 | |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 5 | 7 | 1.00 |

| Hemorrhage | 3 | 8 | 0.50 |

| Bile fistula | 3 | 8 | 0.50 |

| Intraabdominal collection | 4 | 10 | 0.30 |

| Intraabdominal infection | 3 | 12 | 0.07 |

| Wound infection | 3 | 8 | 0.50 |

| Pneumonia | 1 | 3 | 0.87 |

| Urinary tract infection | 1 | 1 | 1.00 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 0 | 0.86 |

| Heart failure | 0 | 2 | 0.63 |

| Myocardial infarction | 1 | 0 | 0.86 |

| Hospital stay | 31.2 ± 11.3 | 36.0 ± 14.6 | 0.07 |

PF was the most frequent complication after PD. The PF rate (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 19.6% vs 30.8%, P = 0.19) and the prevalence of grade A PF (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 13.0% vs 7.7%, P = 0.54) were comparable between the two groups. However, the incidence of clinical PF was significantly lower in the AIT group, compared with the non-AIT group (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 6.5% vs 23.1%, P = 0.02). In addition, 2 patients (of the 10 who experienced repair or re-anastomosis) suffered from grade A PF. Moreover, the overall PF rate, grade A PF rate and clinical PF rate of the remaining 36 patients in the AIT group who did not receive repair or re-anastomosis were 19.4% (n = 7), 11.1% (n = 4) and 8.3% (n = 3), respectively. Interestingly, the statistical analysis revealed that the overall PF rate, grade A PF rate and clinical PF rate of the 36 patients were similar to those of the 65 patients in the non-AIT group (P > 0.05), supporting the contribution of the repair or re-anastomosis after the air insufflation test to the significant reduction of clinical PF in the AIT group. No special treatments were performed for the patients with grade A PF. Radiologic or surgical intervention for PF was required for 1 patient in the AIT group and 8 patients in the non-AIT group. Other patients were treated conservatively with enteral or parenteral nutrition, a somatostatin analog and antibiotics. The length of hospital stay was 34.0 ± 14.5 d for all of the patients, and the length of hospital stay for the AIT group was shorter than for the non-AIT group. However, this difference was only a statistical trend (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 31.2 ± 11.3 d vs 36.0 ± 14.6 d, P = 0.07).

Two patients died during this clinical study (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 1 vs 1, P = 1.00), and they both died due to intra-abdominal infection and hemorrhage related to PF.

Multiple variables related to clinical PF were statistically analyzed with univariate analysis (Table 4), and four risk factors were identified: estimated blood loss; pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm; invagination anastomosis technique; and not undergoing the air insufflation test.

| Clinical PF group (n = 18) | Non-clinical PF group (n = 93) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 56.6 ± 9.8 | 56.4 ± 10.3 | 0.96 |

| Gender | 0.58 | ||

| Male | 10 | 45 | |

| Female | 8 | 48 | |

| ASA | 0.55 | ||

| II | 17 | 80 | |

| III | 1 | 13 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 263.8 ± 298.9 | 191.8 ± 179.7 | 0.17 |

| AST (U/L) | 171.6 ± 232.3 | 135.8 ± 130.2 | 0.36 |

| Preoperative bilirubin (μmol/L) | 185.8 ± 159.8 | 151.2 ± 149.1 | 0.38 |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L) | 68.1 ± 6.8 | 65.6 ± 8.2 | 0.23 |

| Presence of comorbid illness | 5 | 38 | 0.30 |

| Mellitus diabetes | 0 | 11 | 0.27 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1 | 5 | 1.00 |

| Artery hypertension | 1 | 16 | 0.37 |

| Coronaropathy | 3 | 6 | 0.33 |

| Preoperative biliary drainage | 0.25 | ||

| Yes | 11 | 43 | |

| No | 7 | 50 | |

| Smoking | 0.84 | ||

| Yes | 5 | 22 | |

| No | 13 | 71 | |

| Operative factors | |||

| Combined vascular resection | 1 | 2 | 0.42 |

| Duration of operation (min) | 392.8 ± 103.3 | 349.2 ± 93.2 | 0.08 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL) | 428.9 ± 272.6 | 290.2 ± 144.0 | 0.05 |

| Blood transfusion cases | 7 | 26 | 0.35 |

| Pancreatic factors | |||

| Pancreatic duct diameter | 0.02 | ||

| ≤ 3 mm | 16 | 57 | |

| > 3 mm | 2 | 36 | |

| Pancreatic texture | 0.66 | ||

| Soft | 15 | 70 | |

| Hard | 3 | 23 | |

| Pancreatic anastomosis | 0.02 | ||

| Duct to mucosa anastomosis | 2 | 38 | |

| Invagination anastomosis | 16 | 55 | |

| Air insufflation test | 0.02 | ||

| Yes | 3 | 43 | |

| No | 15 | 50 | |

| Pathological diagnoses | 0.96 | ||

| Malignant disease | 15 | 81 | |

| Pancreatic carcinoma | 4 | 20 | 1.00 |

| Ampullar carcinoma | 1 | 17 | 0.32 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 4 | 15 | 0.78 |

| Duodenal carcinoma | 6 | 17 | 0.26 |

| Benign diseases | 3 | 12 |

These variables were further analyzed in multivariate analysis. The estimated blood loss, pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm and not undergoing the air insufflation test were identified as independent risk factors (P = 0.02, 0.00 and 0.00; OR = 1.00, 28.73 and 18.00; and 95%CI: 1.00-1.01, 4.39-188.17 and 3.49-92.96, respectively) for clinical PF.

Despite the evolution of surgical techniques, the PF rate after PD has remained high. PF is one of the most frequent lethal complications after PD. Palani Velu et al[27] reported that serum amylase on the night of surgery predicted clinically significant PF after PD. Molinari et al[28] and Hashimoto et al[29] both demonstrated that the amylase levels of PF patients were significantly higher than those of non-PF patients on the first postoperative day. These reports indicated that some PFs might be caused by unsuccessful anastomoses that went undiscovered during surgery, leading to the elevation of amylase levels in the drainage fluid on the first night and first postoperative day. In the present study, we used the air insufflation test to investigate the pancreatojejunal anastomosis expecting to discover the leakage during operation and repair it immediately. The air insufflation test could detect an incomplete anastomosis and was more sensitive than visual examination, with which it was often difficult to find minor leakage because of hemorrhage.

The air insufflation test did not prolong the operation time; rather, it improved the patient outcomes significantly and was simple and effective. However, there were some particularly important points to note during the testing process. We suggest that the air should be gently injected, and the pressure within the jejunum stump should be monitored throughout the entire process. Acute pancreatitis can be caused if too much air is injected, or the air is injected too quickly. When re-anastomosis is needed, a duct to mucosa anastomosis should usually be changed to an invagination anastomosis if the leakage cannot be resolved after twice re-anastomoses. In the present study, anastomotic revision was conducted in 10 patients. Of these patients, one patient experienced three times pancreaticojejunal re-anastomoses, and PF was not observed until the patient was discharged.

In accordance with the ISGPF definition[24], the PFs in this study were classified as grade A, B or C, based on the clinical impact on the patients’ in-hospital outcomes. Grade A is also called ‘‘transient fistula,’’ and it has no clinical impact[24]. Poor patient outcomes have primarily been caused by grade B and grade C PFs. Fuks et al[12] examined grade C PFs in a multiple center study. They reported a reoperation rate of 97% and a mortality rate of 38.8% for grade C patients. In this study, two patients died postoperatively, and both deaths were caused by grade C PFs. The clinical PF rate (grade B and grade C) was significantly reduced in the AIT group compared with the non-AIT group (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 6.5% vs 23.1%, P = 0.02), and the radiologic or surgical intervention rate was also reduced. However, no significant difference was found (AIT group vs non-AIT group, 2.2% vs 12.3%, P = 0.12).

The current study also identified pancreatic duct diameter less than 3 mm and estimated blood loss as independent risk factors for clinical PF, consistent with previous studies[5,6,8,30]. Duct to mucosa anastomosis was identified as a risk factor for clinical PF in univariate analysis. Different anastomosis techniques have been reported in previous studies. Pancreatic duct to jejunal mucosa anastomosis has been advocated in many series[31,32]. Tsuji et al[33] reported on 300 patients who underwent PD, and the incidence of fistula in the patients who received continuous suture of the pancreatic duct to the jejunal mucosa (4.2%) was significantly less than that of the patients who received interrupted sutures (17.2%) (P < 0.01). Lee et al[34] revealed that continuous sutures for the outer layer of the pancreaticojejunostomy could significantly reduce the PF rate, compared with interrupted sutures. Interrupted suturing of the duct to the mucosa and to the outer layer of the pancreaticojejunostomy was performed in our study, and the clinical PF rate was also statistically less than with the invagination technique. The pancreatic texture has been reported as a risk factor for PF in many studies[2,8]. The incidence of soft remnant pancreas in the clinical PF group was higher than in the non-clinical PF group (83.3% vs 75.3%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05).

In conclusion, the present study confirmed the efficacy of the air insufflation test in preventing clinical PF. It was simple to conduct and could significantly reduce the incidence of clinical PF. Estimated blood loss, pancreatic duct diameter ≤ 3 mm and not undergoing the air insufflation test were identified as independent risk factors for clinical PF in multivariate analysis. This study was retrospective and carried multiple biases. Due to the relatively small number of patients included, additional research is needed to confirm the efficacy of the air insufflation test.

Pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD) has been the standard operation for the resection of periampullary diseases. Unfortunately, regardless of improved surgical techniques and postoperative care, the pancreatic fistula (PF) rate after PD has remained approximately 30%. Moreover, PF has been a primary factor linked with death after PD in some case studies.

Different risk factors have been identified to predict PF, and numerous strategies have been reported to prevent PF. However, their efficacy has been controversial, and these strategies have not been routinely used in most medical centers. More effective and confirmative strategies are needed to reduce the incidence of PF.

Although different strategies have been adopted to prevent PF, none of them can identify whether pancreatic leakage occurs during surgery. The air insufflation test detected pancreatic leakage during the surgery, and its efficacy was also confirmed. Additionally, the risk factors related to PF were also identified in this article.

The air insufflation test could detect pancreatic leakage during PD. In the future, it might be used to identify whether leakage exists in other anastomoses, such as the hepaticojejunal anastomosis.

PF is defined as drainage output of any measurable volume of fluid on or after postoperative day 3 with an amylase content greater than 3 times the serum amylase activity.

Interesting study looking at the use of insufflation of the pancreaticojejeunostomy with air to test for leaks to attempt to minimize the risk of PF. This is a useful contribution to the surgical literature.

P- Reviewer: El Nakeeb A, Merrett ND S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, Huang ZS, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg. 2007;245:443-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Pratt WB, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Risk prediction for development of pancreatic fistula using the ISGPF classification scheme. World J Surg. 2008;32:419-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Reid-Lombardo KM, Farnell MB, Crippa S, Barnett M, Maupin G, Bassi C, Traverso LW. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy in 1,507 patients: a report from the Pancreatic Anastomotic Leak Study Group. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1451-148; discussion 1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gouma DJ, van Geenen RC, van Gulik TM, de Haan RJ, de Wit LT, Busch OR, Obertop H. Rates of complications and death after pancreaticoduodenectomy: risk factors and the impact of hospital volume. Ann Surg. 2000;232:786-795. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Muscari F, Suc B, Kirzin S, Hay JM, Fourtanier G, Fingerhut A, Sastre B, Chipponi J, Fagniez PL, Radovanovic A. Risk factors for mortality and intra-abdominal complications after pancreatoduodenectomy: multivariate analysis in 300 patients. Surgery. 2006;139:591-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 186] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Choe YM, Lee KY, Oh CA, Lee JB, Choi SK, Hur YS, Kim SJ, Cho YU, Ahn SI, Hong KC. Risk factors affecting pancreatic fistulas after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6970-6974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El Nakeeb A, Salah T, Sultan A, El Hemaly M, Askr W, Ezzat H, Hamdy E, Atef E, El Hanafy E, El-Geidie A. Pancreatic anastomotic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Risk factors, clinical predictors, and management (single center experience). World J Surg. 2013;37:1405-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yang YM, Tian XD, Zhuang Y, Wang WM, Wan YL, Huang YT. Risk factors of pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2456-2461. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Lin JW, Cameron JL, Yeo CJ, Riall TS, Lillemoe KD. Risk factors and outcomes in postpancreaticoduodenectomy pancreaticocutaneous fistula. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:951-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 282] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Okabayashi T, Kobayashi M, Nishimori I, Sugimoto T, Onishi S, Hanazaki K. Risk factors, predictors and prevention of pancreatic fistula formation after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2007;14:557-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kawai M, Kondo S, Yamaue H, Wada K, Sano K, Motoi F, Unno M, Satoi S, Kwon AH, Hatori T. Predictive risk factors for clinically relevant pancreatic fistula analyzed in 1,239 patients with pancreaticoduodenectomy: multicenter data collection as a project study of pancreatic surgery by the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2011;18:601-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fuks D, Piessen G, Huet E, Tavernier M, Zerbib P, Michot F, Scotte M, Triboulet JP, Mariette C, Chiche L. Life-threatening postoperative pancreatic fistula (grade C) after pancreaticoduodenectomy: incidence, prognosis, and risk factors. Am J Surg. 2009;197:702-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Callery MP, Pratt WB, Kent TS, Chaikof EL, Vollmer CM. A prospectively validated clinical risk score accurately predicts pancreatic fistula after pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:1-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 653] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Lermite E, Pessaux P, Brehant O, Teyssedou C, Pelletier I, Etienne S, Arnaud JP. Risk factors of pancreatic fistula and delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy with pancreaticogastrostomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:588-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Wellner U, Makowiec F, Fischer E, Hopt UT, Keck T. Reduced postoperative pancreatic fistula rate after pancreatogastrostomy versus pancreaticojejunostomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:745-751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marczell AP, Stierer M. Partial pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) for pancreatic malignancy: occlusion of a non-anastomosed pancreatic stump with fibrin sealant. HPB Surg. 1992;5:251-29; discussion 259-60. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Iannitti DA, Coburn NG, Somberg J, Ryder BA, Monchik J, Cioffi WG. Use of the round ligament of the liver to decrease pancreatic fistulas: a novel technique. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:857-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Choi SB, Lee JS, Kim WB, Song TJ, Suh SO, Choi SY. Efficacy of the omental roll-up technique in pancreaticojejunostomy as a strategy to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Arch Surg. 2012;147:145-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gebhardt C, Stolte M, Schwille PO, Zirngibl H, Engelhardt W. Experimental studies on pancreatic duct occlusion with prolamine. Horm Metab Res Suppl. 1983;9-11. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Duffas JP, Suc B, Msika S, Fourtanier G, Muscari F, Hay JM, Fingerhut A, Millat B, Radovanowic A, Fagniez PL. A controlled randomized multicenter trial of pancreatogastrostomy or pancreatojejunostomy after pancreatoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2005;189:720-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Tani M, Kawai M, Hirono S, Hatori T, Imaizumi T, Nakao A, Egawa S, Asano T, Nagakawa T, Yamaue H. Use of omentum or falciform ligament does not decrease complications after pancreaticoduodenectomy: nationwide survey of the Japanese Society of Pancreatic Surgery. Surgery. 2012;151:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Schulick RD, Yoshimura K. Stents, glue, etc.: is anything proven to help prevent pancreatic leaks/fistulae? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1184-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lowy AM, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Davidson BS, Fenoglio CJ, Stanford P, Jinnah R, Evans DB. Prospective, randomized trial of octreotide to prevent pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy for malignant disease. Ann Surg. 1997;226:632-641. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, Neoptolemos J, Sarr M, Traverso W, Buchler M. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3282] [Cited by in RCA: 3512] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (34)] |

| 25. | Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG, Traverso LW. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS). Surgery. 2007;142:761-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1771] [Cited by in RCA: 2328] [Article Influence: 129.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wente MN, Veit JA, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, Neoptolemos JP, Padbury RT, Sarr MG. Postpancreatectomy hemorrhage (PPH): an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) definition. Surgery. 2007;142:20-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1411] [Cited by in RCA: 1946] [Article Influence: 108.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Palani Velu LK, Chandrabalan VV, Jabbar S, McMillan DC, McKay CJ, Carter CR, Jamieson NB, Dickson EJ. Serum amylase on the night of surgery predicts clinically significant pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:610-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Molinari E, Bassi C, Salvia R, Butturini G, Crippa S, Talamini G, Falconi M, Pederzoli P. Amylase value in drains after pancreatic resection as predictive factor of postoperative pancreatic fistula: results of a prospective study in 137 patients. Ann Surg. 2007;246:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hashimoto N, Ohyanagi H. Pancreatic juice output and amylase level in the drainage fluid after pancreatoduodenectomy in relation to leakage. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:553-555. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Poon RT, Fan ST, Lo CM, Ng KK, Yuen WK, Yeung C, Wong J. External drainage of pancreatic duct with a stent to reduce leakage rate of pancreaticojejunostomy after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2007;246:425-33; discussion 433-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Prenzel KL, Hölscher AH, Grabolle I, Fetzner U, Kleinert R, Gutschow CA, Stippel DL. Impact of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy with external drainage of the pancreatic duct after pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Surg Res. 2011;171:558-562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fragulidis GP, Arkadopoulos N, Vassiliou I, Marinis A, Theodosopoulos T, Stafyla V, Kyriazi M, Karapanos K, Dafnios N, Polydorou A. Pancreatic leakage after pancreaticoduodenectomy: the impact of the isolated jejunal loop length and anastomotic technique of the pancreatic stump. Pancreas. 2009;38:e177-e182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tsuji M, Kimura H, Konishi K, Yabushita K, Maeda K, Kuroda Y. Management of continuous anastomosis of pancreatic duct and jejunal mucosa after pancreaticoduodenectomy: historical study of 300 patients. Surgery. 1998;123:617-621. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Lee SE, Yang SH, Jang JY, Kim SW. Pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a comparison between the two pancreaticojejunostomy methods for approximating the pancreatic parenchyma to the jejunal seromuscular layer: interrupted vs continuous stitches. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5351-5356. [PubMed] |