Published online Dec 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13524

Peer-review started: June 25, 2015

First decision: July 19, 2015

Revised: August 7, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: December 28, 2015

Processing time: 187 Days and 5.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the dynamic computed tomography (CT) findings of liver metastasis from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach (HAS) and compared them with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

METHODS: Between January 2000 and January 2015, 8 patients with pathologically proven HAS and liver metastases were enrolled. Basic tumor status was evaluated for the primary tumor location and metastatic sites. The CT findings of the liver metastases were analyzed for tumor number and size, presence of tumor necrosis, hemorrhage, venous tumor thrombosis, and dynamic enhancing pattern.

RESULTS: The body and antrum were the most common site for primary HAS (n = 7), and observed metastatic sites included the liver (n = 8), lymph nodes (n = 7), peritoneum (n = 4), and lung (n = 2). Most of the liver metastases exhibited tumor necrosis regardless of tumor size. By contrast, tumor hemorrhage was observed only in liver lesions larger than 5 cm (n = 4). Three patterns of venous tumor thrombosis were identified: direct venous invasion by the primary HAS (n = 1), direct venous invasion by the liver metastases (n = 7), and isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis (n = 2). Dynamic CT revealed arterial hyperattenuation and late phase washout in all the liver metastases.

CONCLUSION: On dynamic CT, liver metastasis from HAS shared many imaging similarities with HCC. For liver nodules, the presence of isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis and a tendency for tumor necrosis are imaging clues that suggest the diagnosis of HAS.

Core tip: Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach (HAS) is a rare form of gastric cancer with clinicopathological presentation mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The high similarity between the two diseases makes the differential diagnosis challenging, especially when the primary tumor is unknown, and the liver nodules are the only initial finding. In the present study, identical dynamic enhancing pattern (arterial hyperattenuation and late phase washout) between liver metastasis from HAS and HCC was confirmed. Moreover, the presence of isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis and a tendency of tumor necrosis are the imaging clues that suggest the diagnosis of HAS rather than HCC.

- Citation: Lin YY, Chen CM, Huang YH, Lin CY, Chu SY, Hsu MY, Pan KT, Tseng JH. Liver metastasis from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: Dynamic computed tomography findings. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(48): 13524-13531

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i48/13524.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i48.13524

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach (HAS) is a rare form of gastric cancer with clinicopathological presentation mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Clinically, the neoplasm is characterized by a predilection for older age, high serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, an aggressive clinical course, and poor prognosis[1]. The aggressive tumor behavior makes the liver metastasis being as the first clinical manifestation in more than 75% of HAS patients[2]. Pathologically, hepatoid morphology, immunoreactivity with AFP, and a tendency for vascular permeation are the shared features of HAS and HCC[3]. The high similarity between the two diseases makes differential diagnosis challenging, especially when the primary tumor is unknown, and the liver nodules are the only initial finding. Moreover, the role of dynamic computed tomography (CT) in liver metastasis from HAS is not well established. To our knowledge, only one case report mentioned a similar dynamic enhancing pattern in liver metastasis from HAS and HCC[4]. The aim of our study was to evaluate the dynamic CT findings of liver metastasis from HAS and compare them with the typical imaging findings of HCC. The clinical presentation and treatment results of HAS are also evaluated.

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, and the need for patient informed consent was waived because of the retrospective and anonymous nature of this study. A retrospective search of January 2000 to January 2015 revealed 11 patients with pathologically proven HAS and liver metastases in our institution. Three patients were excluded because their CT studies were not available for review. Finally, 8 patients (6 men and 2 women; mean age 68.5 ± 6.1 years; range 60-78 years) constituted our study cohort. Clinical data including patient demographics, initial presentation, personal history (alcohol use and hepatitis infection), laboratory data (hemoglobin level and serum AFP level), treatments received, and therapeutic result were reviewed.

CT examinations were requested in regard to clinical symptoms, abnormal liver ultrasound results, or abnormal endoscopic findings. Four patients underwent three-phase dynamic CT of the liver, 2 patients underwent two-phase dynamic CT for gastric tumor staging, and routine abdominal CT was arranged for the remaining 2 patients. Each patient received 100 mL of a nonionic, low-osmolar contrast material (Iohexol, Omnipaque, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, United States) administered intravenously at a rate of 2.5-3.0 mL/s. Dynamic CT scanning was conducted at 30 s (arterial phase) and 60 s (portal venous phase) after the beginning of intravenous injection. Additional scanning at 3 min (equilibrium phase) was included in the protocol of dynamic CT of the liver. For patients that underwent CT for gastric tumor staging, a total of 800-1000 mL of tap water was administered orally to obtain gastric distension just prior to scanning. Images were routinely reconstructed into coronal and sagittal planes and available for viewing on a picture-archiving and communication system (PACS, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, United States).

CT images were retrospectively reviewed by two board-certified radiologists in consensus. Basic tumor status was evaluated for the primary tumor location, tumor size, and metastatic sites (for both nodal metastasis and distant metastasis). Image findings of liver metastases were analyzed for the following factors: tumor number and size, presence of tumor necrosis, hemorrhage, venous tumor thrombosis, and dynamic enhancing pattern. The presence of a gastric tumor was suggested when the gastric wall was 6 mm or greater in thickness or with abnormal contrast enhancement[5]. Lymph node involvement was considered as present when the short-axis diameter is larger than 8 mm for perigastric lymph nodes and larger than 10 mm for distant lymph nodes[6,7]. The attenuation of tumor content was analyzed as Hounsfield units[4] when a region of interest was placed in the center of the lesion. The presence of a low-attenuation (10-30 HU), nonenhancing area within the tumor was defined as tumor necrosis[8]. By contrast, tumor hemorrhage was considered as a high-attenuation (50-100 HU), nonenhancing area within the tumor[9]. Venous tumor thromboses, including those of the portal veins, hepatic veins, inferior vena cava, and perigastric veins, were judged by identifying intravenous filling defects with enlargement of the involved venous segment and with minimal contrast enhancement on portal venous phase of CT[10-12]. Isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis was defined as the presence of tumor thrombosis of the portal vein without evidence of liver metastasis of the ipsilateral liver lobe[13]. The degree of tumor attenuation (hypoattenuation, isoattenuation, and hyperattenuation) on CT studies was determined by the largest lesion against the background of the adjacent normal liver parenchyma on arterial phase and late phase (portal venous and equilibrium phases) images[14]. Heterogeneously enhancing lesions were classified as hyperattenuating when most of the solid component was well-enhanced[15]. Washout was defined as occurring when any part of the lesion that was hyperattenuating on arterial phase images exhibited a corresponding hypoattenuating area on late phase images[14].

Table 1 summarizes the relevant clinical information and basic tumor status of the enrolled patients. Among the 8 patients with pathologically proven HAS and liver metastasis, 6 were male and the mean age at diagnosis was 68.5 ± 6.1 years. All patients were serologically negative for hepatitis B and C, had no history of alcohol abuse, and did not exhibit any clinical or imaging signs of liver cirrhosis. Markedly elevated serum AFP levels (mean 2295.9 ± 1942.8 ng/mL; range 281.1-6442.6 ng/mL) and various degrees of anemia (mean 8.3 ± 0.9 g/dL; range 6.8-9.4 g/dL) were the main laboratory abnormalities. In 4 patients, the symptoms (epigastric discomfort and palpable mass) led to the ultrasonographic detection of hepatic nodules as the initial clinical finding. Only 25% of the patients (n = 2) underwent endoscopy prior to CT examinations. The metastatic tumor status made Fluorouracil (5-FU)-based chemotherapy being as the main treatment for most of the patients (n = 7). Three patients complicated with gastric outlet obstruction were treated with palliative distal gastrectomy, and transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) with Lipiodol and Doxorubicin infusion was performed for liver metastases in 3 patients. Supportive care was suggested for one patient because of poor performance status. The mean survival time from the first diagnosis was 8.9 ± 7.8 mo (range 3-23 mo).

| Case No. | Sex/age (yr) | Initial presentation | Location(largest size, cm) | Metastasis | Serum AFP(ng/mL) | Treatment | Follow-up status |

| 1 | M/64 | Epigastric discomfort | Body, antrum (7.5) | Liver | 1133.7 | Gastrectomy | Died at 19 mo |

| Peritoneum | Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Perigastric lymph nodes | TACE for liver metastases | ||||||

| 2 | M/69 | Body weight loss | Antrum (7.3) | Liver | 281.1 | Gastrectomy | Died at 3 mo |

| Lung | Chemotherapy | ||||||

| 3 | M/78 | Epigastric discomfort | Antrum (4.5) | Liver | 3124.9 | Gastrectomy | Died at 5 mo |

| Perigastric lymph nodes | Chemotherapy | ||||||

| 4 | M/63 | Epigastric discomfort | Cardia (5.2) | Liver | 2170.3 | Chemotherapy | Died at 6 mo |

| Peritoneum | TACE for liver metastases | ||||||

| Perigastric lymph nodes | |||||||

| 5 | F/70 | Palpable mass | Body, antrum (3.8) | Liver | 890.3 | Chemotherapy | Died at 23 mo |

| Perigastric lymph nodes | TACE for liver metastases | ||||||

| 6 | F/69 | Epigastric discomfort | Body, antrum (7.5) | Liver | 6442.6 | Chemotherapy | Died at 9 mo |

| Perigastric lymph nodes | |||||||

| 7 | M/60 | Epigastric discomfort | Antrum (4.5) | Liver | 1419.7 | Chemotherapy | Died at 3 mo |

| Peritoneum | |||||||

| Paraaortic lymph nodes | |||||||

| Perigastric lymph nodes | |||||||

| 8 | M/75 | Body weight loss | Body (4.0) | Liver | 2904.5 | Supportive care | Died at 3 mo |

| Lung | |||||||

| Peritoneum | |||||||

| Perigastric lymph nodes |

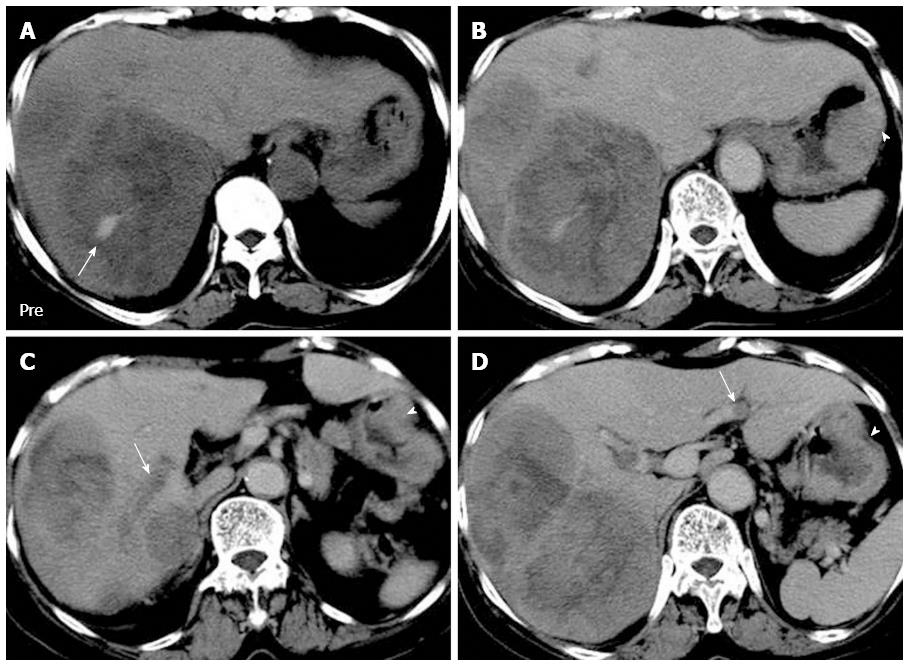

The body and antrum were the most common site for primary HAS (n = 7; mean size 5.5 ± 1.6 cm), and the observed metastatic sites included the liver (n = 8), lymph nodes (n = 7), peritoneum (n = 4), and lung (n = 2). Table 2 summarizes the CT characteristics of the liver metastases from HAS. Liver metastases usually presented as multiple nodules with variable sizes (n = 5), but single presentation was also noted (n = 3). Most of the liver metastases exhibited tumor necrosis regardless of tumor size. By contrast, tumor hemorrhage was observed only in liver lesions larger than 5 cm (n = 4). Venous tumor thrombosis was identified in 7 patients, and the locations included the portal veins (n = 7), hepatic veins (n = 3), inferior vena cava (n = 2), and gastroepiploic vein (n = 1). Three patterns of venous tumor thrombosis were found: direct venous invasion by the primary HAS (n = 1), direct venous invasion by the liver metastases (n = 7), and isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis (n = 2). Dynamic CT revealed arterial hyperattenuation and late phase washout in all the liver metastases.

| Case No. | Tumor location | Tumor number(largest size, cm) | Necrosis | Hemorrhage | Venous tumor thrombus | Dynamic enhancing pattern |

| 1 | Lateral segment | Single (9.7) | Yes | No | Left portal vein | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Left hepatic vein | Late phase washout | |||||

| Inferior vena cava | ||||||

| 2 | Bilateral lobes | Multiple (8.7) | Yes | Yes | Right portal vein | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Left hepatic vein | Late phase washout | |||||

| Inferior vena cava | ||||||

| 3 | Segment 7 | Single (2.1) | Yes | No | Right portal vein | NA |

| 4 | Right lobe | Multiple (2.8) | Yes | No | Right portal vein | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Left portal vein1 | Late phase washout | |||||

| 5 | Segment 4 | Single (7.2) | Yes | No | nil | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Late phase washout | ||||||

| 6 | Right lobe | Multiple (9.8) | Yes | Yes | Right portal vein | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Left portal vein1 | Late phase washout | |||||

| Gastroepiploitc vein2 | ||||||

| 7 | Bilateral lobes | Multiple (7.5) | Yes | Yes | Right portal vein | Arterial hyperattenuation |

| Left hepatic vein | Late phase washout | |||||

| 8 | Bilateral lobes | Multiple (8.1) | Yes | Yes | Left portal vein | NA |

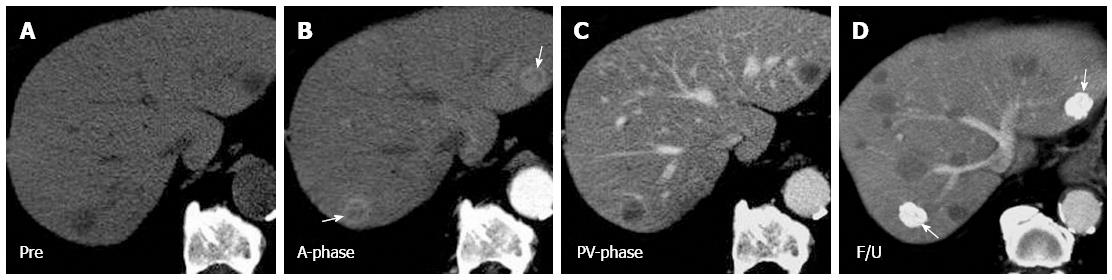

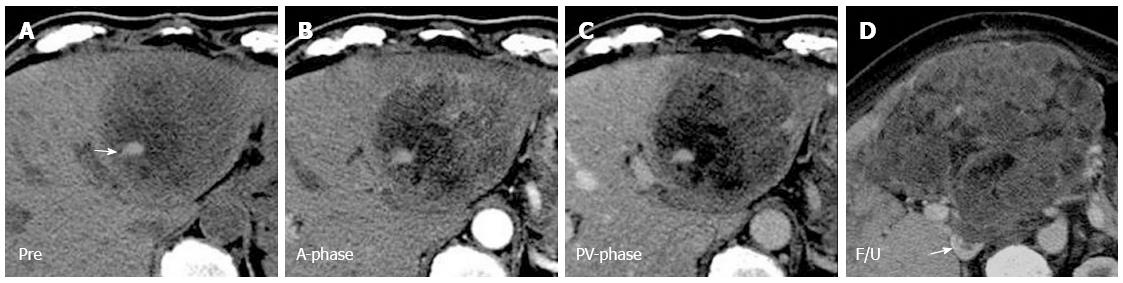

The typical dynamic enhancing pattern of HCC is arterial hyperattenuation followed by washout on late phase images[16]. This pattern is consistent with a multistep process of hepatocarcinogenesis, which results in tumor vascular changes toward a predominant hepatic arterial supply with a lack of portal venous inflow[17,18]. According to the diagnostic guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases in 2010[19], in patients with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis B, liver nodules larger than 1 cm with typical enhancing pattern on contrast-enhanced CT can be considered HCC and the need for biopsy is obviated. In our study, all the liver metastases from HAS presented with arterial hyperattenuation and washout on dynamic CT studies (Figures 1 and 2). The identical dynamic enhancing pattern, accompanied with high serum AFP levels, makes liver metastasis from HAS a great mimic of HCC. Clinically, HAS is characterized by the absence of risk factors for HCC[20]. However, in endemic areas with a high incidence of chronic hepatitis B, chronic hepatitis C, and cirrhosis, a HAS patient being a hepatitis carrier or cirrhotic patient simultaneously may not be rare[21].

In our study, most of the liver metastases from HAS exhibited tumor necrosis regardless of tumor size. Central necrosis can be detected even in liver nodules with a diameter of less than 1 cm (Figure 1). By contrast, spontaneous central necrosis occurs only in HCCs larger than 3 cm[22], and the reported necrosis rate for HCC is relatively low (10%-40%)[23]. For liver metastases from HAS, the high incidence of tumor necrosis is believed to be due to outgrowth of the blood supply by the tumor causing hypoxia and subsequent necrosis at the center of the tumor[24].

The tendency for tumor hemorrhage was a shared feature between liver metastasis from HAS and HCC. In our study, tumor hemorrhage was observed only in liver lesions larger than 5 cm (Figure 2). Similarly, HCC with a larger diameter carried a higher risk of tumor hemorrhage[25]. Intratumoral bleeding is usually a result of local ischemia caused by rapid growth of the lesion[26]. In 3%-26% of patients with HCC, hemoperitoneum occurs after tumor bleeding[27,28]. By contrast, neither hemoperitoneum nor tumor rupture has been reported in patients with HAS.

Lee et al[7] proposed two patterns of liver metastasis from HAS: a dominant bulky mass with adjacent portal vein tumor thrombosis and multiple nodules of a similar size without tumor thrombosis. The dominant bulky mass pattern was reported to be more common. In our study, a predilection existed for a dominant bulky mass (Figures 2 and 3). However, the tumor number and size were unrelated to the presence of portal vein tumor thrombosis. On CT images, most of the tumor thromboses were caused by direct venous invasion of the metastatic liver tumors (Figure 3C). Similarly, most of the reported venous tumor thromboses in HCC were caused by direct tumor invasion[29]. In one patient with gastroepiploic vein tumor thrombosis, the tendency for vascular permeation by the primary HAS was demonstrated. This finding supports those of two previous studies[4,7]. Moreover, our study demonstrated a unique type of venous tumor thrombosis: isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis (Figure 3D). This finding implies a possible route of tumor spread for the primary HAS and could be useful in differential diagnosis.

A percutaneous liver biopsy is usually performed as a problem-solving tool on liver nodules of uncertain nature. However, the procedure may play a limited role in differentiation between liver metastasis from HAS and HCC. HAS shares strikingly morphologic similarity with HCC in histology[20]. Routine immunohistochemical stains, like AFP, HepPar1, and GPC-3, are useful but not specific for differential diagnosis[21]. Although some novel immunohistochemical markers, such as PIVKA-II[30], CEA, PLUNC, and CK19[3], have exhibited varying degrees of ability in differentiation, they are performed only upon adequate clinical and imaging suspicions of HAS. By contrast, for patients with suspected HAS and liver metastasis, liver biopsy along with endoscopic biopsy can be performed to confirm the identical tumor origin in both the liver and stomach, and exclude the diagnosis of synchronous HCC and gastric cancer, which is the most crucial differential diagnosis.

The prognosis of HAS is extremely poor, mainly resulting from the strong tendency for vascular permeation and early distant metastases[4]. Aggressive treatments, such as radical surgery combined with chemotherapy, have been proven to positively affect the clinical outcome of HAS patients[31,32]. Moreover, because striking pathological similarities are shared by HAS and HCC, the treatments recommended for HCC may also be effective for HAS. Petrelli et al[33] suggested Sorafenib (Nexavar, Bayer HealthCare, Montville, NJ, United States) as a possible treatment for hepatoid adenocarcinoma. In our study, TACE was performed along with 5-FU-based systemic chemotherapy in 3 patients. Most of the treated liver nodules were well embolized by densely packed Lipiodol. However, new liver metastases were observed on follow-up CT (Figure 1D), which may be contributed by the continuous tumor spread from the poorly controlled primary HAS through the portal venous system. Our results suggest that TACE, similarly to its role in HCC treatment, may serve as a local therapy for liver nodules of HAS but must be accompanied with systemic chemotherapy or radical surgery for complete tumor control.

The presence of gastric malignancy was not always easily identified on CT images. The detectability of primary HAS was influenced by morphologic features, the thickness of the gastric wall, and the degree of tumor enhancement. Moreover, abdominal CT studies performed as a result of nonspecific initial symptoms or abnormal liver ultrasonographic findings would not follow the standard protocol for gastric tumor staging and would thus impair the detectability of gastric malignancy on CT. D’Elia et al[34] reported conventional CT studies possess a low range of detectability (40%-90%) in preoperative gastric cancer staging. When the primary tumor is unknown, and the liver nodules are the only initial finding, correct diagnosis of HAS can be challenging.

This study has some limitations. First, it is a single-center, retrospective, and nonrandomized study. Because of the rarity of HAS, only 8 patients were enrolled in this study. The small sample size may limit accurate analysis and lead to bias of the results. Second, the presence of venous tumor thrombosis, central necrosis, and intratumoral bleeding was determined according to the imaging criteria, not by histologic proof. However, all the enrolled patients had their HAS confirmed histologically through an operation or biopsy and had no other conditions predisposing them to portal venous thrombosis. Third, this study covered patients over a span of 15 years. Images from different CT scanner with various parameters were included for review. However, this was not a major limitation since the intra-abdominal lesions were usually bulky.

In conclusion, liver metastasis from HAS shared many CT imaging similarities with HCC. For the liver nodules, the presence of isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis and a tendency for tumor necrosis are imaging clues that suggest the diagnosis of HAS. Liver biopsy along with endoscopic biopsy can be performed to confirm the identical tumor origin in both the liver and stomach for the patients with suspicious HAS.

Hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach (HAS) is a rare gastric cancer with clinicopathological presentation mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). The high similarity between the two diseases makes differential diagnosis challenging, especially when the primary tumor is unknown, and the liver nodules are the only initial finding. Moreover, the role of dynamic computed tomography (CT) in liver metastasis from HAS is not well established.

To date, only one case report mentioned the dynamic enhancing pattern in liver metastasis from HAS and HCC. This study was designed to evaluate the dynamic CT findings of liver metastasis from HAS and compare them with the typical imaging findings of HCC.

Identical dynamic enhancing pattern (arterial hyperattenuation and late phase washout) between liver metastasis from HAS and HCC was confirmed in the present study. Moreover, most of the liver metastases from HAS exhibited tumor necrosis regardless of tumor size. Isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis, a unique type of venous tumor thrombosis, implies a possible route of tumor spread for the primary HAS and could be useful in differential diagnosis.

The presence of isolated portal vein tumor thrombosis and a tendency of tumor necrosis are the imaging clues that suggest the diagnosis of HAS rather than HCC.

HAS is a rare gastric cancer, which usually presents high serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, an aggressive clinical course, and poor prognosis. Pathologically, hepatoid morphology, immunoreactivity with AFP, and a tendency for vascular permeation are the shared features of HAS and HCC.

This is a very good paper.

P- Reviewer: Tarazov PG S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Ishikura H, Kishimoto T, Andachi H, Kakuta Y, Yoshiki T. Gastrointestinal hepatoid adenocarcinoma: venous permeation and mimicry of hepatocellular carcinoma, a report of four cases. Histopathology. 1997;31:47-54. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Liu X, Cheng Y, Sheng W, Lu H, Xu X, Xu Y, Long Z, Zhu H, Wang Y. Analysis of clinicopathologic features and prognostic factors in hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:1465-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Terracciano LM, Glatz K, Mhawech P, Vasei M, Lehmann FS, Vecchione R, Tornillo L. Hepatoid adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma: an immunohistochemical and molecular study of eight cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1302-1312. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Jo JM, Kim JW, Heo SH, Shin SS, Jeong YY, Hur YH. Hepatic metastases from hepatoid adenocarcinoma of stomach mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2012;18:420-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim AY, Kim HJ, Ha HK. Gastric cancer by multidetector row CT: preoperative staging. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:465-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dorfman RE, Alpern MB, Gross BH, Sandler MA. Upper abdominal lymph nodes: criteria for normal size determined with CT. Radiology. 1991;180:319-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lee MW, Lee JY, Kim YJ, Park EA, Choi JY, Kim SH, Lee JM, Han JK, Choi BI. Gastric hepatoid adenocarcinoma: CT findings. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:293-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Adams HJ, de Klerk JM, Fijnheer R, Dubois SV, Nievelstein RA, Kwee TC. Prognostic value of tumor necrosis at CT in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Radiol. 2015;84:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Eknoyan G. A clinical view of simple and complex renal cysts. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1874-1876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tublin ME, Dodd GD, Baron RL. Benign and malignant portal vein thrombosis: differentiation by CT characteristics. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:719-723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 207] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ishikawa M, Koyama S, Ikegami T, Fukutomi H, Gohongi T, Yuzawa K, Fukao K, Fujiwara M, Fujii K. Venous tumor thrombosis and cavernous transformation of the portal vein in a patient with gastric carcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:529-533. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Akin O, Dixit D, Schwartz L. Bland and tumor thrombi in abdominal malignancies: magnetic resonance imaging assessment in a large oncologic patient population. Abdom Imaging. 2011;36:62-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Poddar N, Avezbakiyev B, He Z, Jiang M, Gohari A, Wang JC. Hepatocellular carcinoma presenting as an incidental isolated malignant portal vein thrombosis. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:486-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yoon SH, Lee JM, So YH, Hong SH, Kim SJ, Han JK, Choi BI. Multiphasic MDCT enhancement pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma smaller than 3 cm in diameter: tumor size and cellular differentiation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2009;193:W482-W489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Loyer EM, Chin H, DuBrow RA, David CL, Eftekhari F, Charnsangavej C. Hepatocellular carcinoma and intrahepatic peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: enhancement patterns with quadruple phase helical CT--a comparative study. Radiology. 1999;212:866-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marrero JA, Hussain HK, Nghiem HV, Umar R, Fontana RJ, Lok AS. Improving the prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients with an arterially-enhancing liver mass. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim I, Kim MJ. Histologic characteristics of hepatocellular carcinomas showing atypical enhancement patterns on 4-phase MDCT examination. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:586-593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lee J, Lee WJ, Lim HK, Lim JH, Choi N, Park MH, Kim SW, Park CK. Early hepatocellular carcinoma: three-phase helical CT features of 16 patients. Korean J Radiol. 2008;9:325-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020-1022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5972] [Cited by in RCA: 6574] [Article Influence: 469.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Su JS, Chen YT, Wang RC, Wu CY, Lee SW, Lee TY. Clinicopathological characteristics in the differential diagnosis of hepatoid adenocarcinoma: a literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lin CY, Yeh HC, Hsu CM, Lin WR, Chiu CT. Clinicopathologial features of gastric hepatoid adenocarcinoma. Biomed J. 2015;38:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Fernandez MP, Redvanly RD. Primary hepatic malignant neoplasms. Radiol Clin North Am. 1998;36:333-348. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Tanaka N, Okamoto E, Toyosaka A, Fujiwara S. Pathological evaluation of hepatic dearterialization in encapsulated hepatocellular carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1985;29:256-260. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Marchal GJ, Pylyser K, Tshibwabwa-Tumba EA, Verbeken EK, Oyen RH, Baert AL, Lauweryns JM. Anechoic halo in solid liver tumors: sonographic, microangiographic, and histologic correlation. Radiology. 1985;156:479-483. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen CY, Lin XZ, Shin JS, Lin CY, Leow TC, Chen CY, Chang TT. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma. A review of 141 Taiwanese cases and comparison with nonrupture cases. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;21:238-242. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Nakajima T, Moriguchi M, Watanabe T, Noda M, Fuji N, Minami M, Itoh Y, Okanoue T. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma with rapid growth after spontaneous regression. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:3385-3387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lai EC, Lau WY. Spontaneous rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review. Arch Surg. 2006;141:191-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Akriviadis EA. Hemoperitoneum in patients with ascites. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:567-575. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Katagiri S, Yamamoto M. Multidisciplinary treatments for hepatocellular carcinoma with major portal vein tumor thrombus. Surg Today. 2014;44:219-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Tomono A, Wakahara T, Kanemitsu K, Toyokawa A, Teramura K, Iwasaki T. [A surgically resected case of AFP and PIVKA-II producing gastric cancer with hepatic metastasis]. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2013;110:852-860. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Nuevo-Gonzalez JA, Cano-Ballesteros JC, Lopez B, Andueza-Lillo JA, Audibert L. Alpha-Fetoprotein-Producing Extrahepatic Tumor: Clinical and Histopathological Significance of a Case. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43 Suppl 1:28-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang JF, Shi SS, Shao YF, Zhang HZ. Clinicopathological and prognostic features of hepatoid adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Chin Med J (Engl). 2011;124:1470-1476. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Petrelli F, Ghilardi M, Colombo S, Stringhi E, Barbara C, Cabiddu M, Elia S, Corti D, Barni S. A rare case of metastatic pancreatic hepatoid carcinoma treated with sorafenib. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2012;43:97-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | D’Elia F, Zingarelli A, Palli D, Grani M. Hydro-dynamic CT preoperative staging of gastric cancer: correlation with pathological findings. A prospective study of 107 cases. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:1877-1885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |