Published online Dec 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13345

Peer-review started: June 27, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: July 30, 2015

Accepted: September 28, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

Published online: December 21, 2015

Processing time: 171 Days and 18.8 Hours

AIM: To investigate the impact of different surgical techniques on post-operative complications after colorectal resection for endometriosis.

METHODS: A multicenter case-controlled study using the prospectively collected data of 90 women (22 with and 68 without post-operative complications) who underwent laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis was designed to evaluate any risk factors of post-operative complications. The prospectively collected data included: gender, age, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk class, endometriosis localization (from anal verge), operative time, conversion, intraoperative complications, and post-operative surgical complications such as anastomotic dehiscence, bleeding, infection, and bowel dysfunction.

RESULTS: A similar number of complicated cases have been registered for the different surgical techniques evaluated (laparoscopy, single access, flexure mobilization, mesenteric artery ligation, and transvaginal specimen extraction). A multivariate regression analysis showed that, after adjusting for major clinical, demographic, and surgical characteristics, complicated cases were only associated with endometriosis localization from the anal verge (OR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.74-0.98, P = 0.03). After analyzing the association of post-operative complications and each different surgical technique, we found that only bowel dysfunction after surgery was associated with mesenteric artery ligation (11 out of 44 dysfunctions in the mesenteric artery ligation group vs 2 out of 36 cases in the no mesenteric artery ligation group; P = 0.03).

CONCLUSION: Although further randomized clinical trials are needed to give a definitive conclusion, laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis appears to be both feasible and safe. Surgical technique cannot be considered a risk factor of post-operative complications.

Core tip: To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating the impact of different surgical techniques on the occurrence of post-operative complications. We have evaluated the potential influence of the most relevant surgical differences, including: laparoscopic approach, single access laparoscopy, flexure mobilization, mesenteric artery ligation, specimen extraction site, and diverting ileostomy creation.

- Citation: Milone M, Vignali A, Milone F, Pignata G, Elmore U, Musella M, De Placido G, Mollo A, Fernandez LMS, Coretti G, Bracale U, Rosati R. Colorectal resection in deep pelvic endometriosis: Surgical technique and post-operative complications. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(47): 13345-13351

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i47/13345.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13345

Endometriosis is a common condition that affects up to 10% of women in their reproductive years[1]. Deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) is characterized by endometriosis implants that penetrate more than 5 mm into the affected tissue. Although the disease is limited in most patients to the genital organs, endometriosis may diffusely involve pelvic structures such as the bowels and urinary tract[2-5]. The estimated incidence of bowel endometriosis is between 3% and 36%[6], while rectal and rectosigmoid junction involvement together account for 70%-93% of all intestinal endometriotic lesions[7].

Due to the limited efficacy of medical therapy and symptom recurrence rates as high as 76%[8], surgical excision is frequently advocated as the treatment of choice[9,10].

Although it is well known that laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection is preferred for the treatment of colorectal endometriosis, little is known about the impact of different surgical techniques on post-operative complications.

Utilizing prospectively maintained endometriosis databases, all consecutive women who underwent colorectal resection for endometriosis from January 2005 to December 2013 were identified for inclusion in a multicenter study after obtaining local ethics committee approval and signed informed consent. A case-controlled study was designed, including 22 women with and 68 women without post-operative complications, to identify potential risk factors for complications after surgery, with a focus on surgical technique.

Only institutions with a high volume of colorectal surgeries were included, and only prospectively recorded data were analyzed. All consecutive procedures were included in our analyses, according to strict inclusion criteria; all patients operated on by expert surgeons with standardized indications for surgery were included in our analyses. The laparoscopic colectomy learning curve can be considered completed after between 30 and 70 procedures. Thus, only procedures performed by an expert surgeon (i.e., with experience of more than 70 laparoscopic colectomies) were included in the study[11]; furthermore, all procedures were performed by a multidisciplinary surgical team, including an expert colorectal surgeon and a gynecologist. Indications for colorectal resection included the presence of colorectal involvement in deep bowel endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy[12] and of endometriosis-related symptoms (i.e., pelvic pain, dyschezia, rectal bleeding, obstruction, and dyspareunia).

Different surgical approaches were performed according to the clinical advice of each individual surgeon. A propensity score analysis was performed to exclude any bias related to the allocation of each patient into the different surgical technique groups.

Dissection is performed through the rectovaginal septum, where endometriosis implants are frequently found and must be removed. The rectum is mobilized at least 2 cm below the nodule of the endometriosis. A stapler is introduced into the peritoneal cavity, and then the rectum is sectioned. After extracting the rectal stump, the rectum or rectosigmoid (depending on the disease extension) is resected. Then, the head of the EEA (end-to-end) stapler (usually 29 mm) is positioned, the pneumoperitoneum is reconstituted, and a transanal end-to-end colorectal anastomosis is performed according to the Knight-Griffen technique. According to the clinical advice of each surgeon, flexure mobilization, mesenteric artery ligation, diverting ileostomy, or transvaginal colon extraction may be performed.

To minimize the bias related to the use of differing post-surgical managements, the post-operative period was homogenized to exclude patients who received different medical and nursing care. Specifically, on post-operative day 1, endovenous hydration was suspended, and the patients were allowed to drink liquids and consume oral medicines. Criteria for discharge included symptom absence, tolerance of a minimum of three meals without restrictions, and stool passage.

Prospectively collected data included gender, age, body mass index (BMI), American Society of Anesthesiologists risk class, endometriosis localization (from anal verge), operative time, conversion, intraoperative complications, and post-operative surgical complications such as anastomotic dehiscence, bleeding, infection, and bowel dysfunction.

Short-term follow-up was conducted at 5 and 30 d after discharge. All adverse events that occurred within 90 d after surgery were considered to be complications.

The term anastomotic leakage defines all conditions with clinical or radiologic anastomotic dehiscence, with or without the need for surgical revision. Any bleeding led to an evaluation to determine if a blood transfusion was required. Bowel dysfunction was considered if any problems with the frequency, consistency, and/or ability to control bowel movements occurred after surgery.

Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Continuous data are expressed as the mean ± SD, with categorical variables expressed as a percentage. To compare continuous variables, an independent sample t-test was performed. The Wilcoxon test for paired samples was employed as a non-parametric equivalent of the paired sample t-test used for continuous variables. The χ2 test was employed to analyze categorical data. When the minimum expected value was < 5, Fisher’s exact test was used. All results are presented as 2-tailed values with statistical significance if P values were < 0.05. To adjust for all the other variables and to make predictions, multivariate analyses were performed with post-operative complication occurrence (logistic regression) as dependent variables, and with major clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as surgical approach, as independent variables.

Demographics and disease-related data for each cohort are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences in terms of age, BMI, or symptoms between the two groups.

| Complicated cases (22) | Uncomplicated cases (68) | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 33 ± 5.5 | 35.2 ± 5.3 | 0.11 |

| BMI | 24 ± 4 | 24 ± 2.9 | 0.96 |

| Symptoms (pts) | 17 (77.7) | 54 (79.4) | 1.00 |

| Pain | 7 (31.8) | 15 (22) | 0.46 |

| Dyspareunia | 5 (22.7) | 17 (25) | 0.78 |

| Rectal bleeding | 9 (40.9) | 30 (44.1) | 1.00 |

| Constipation | |||

| localization (cm from anal verge) | 12.4 ± 4.8 | 13.9 ± 4.4 | 0.17 |

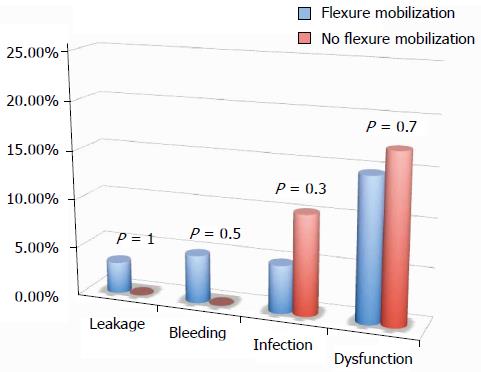

Operative time (207.1 ± 53.3 min in complicated cases vs 206.7 ± 8 min in uncomplicated cases) was similar in both groups (P = 0.98). Interestingly, multivariate analysis (linear regression) showed that, after adjusting for different surgical techniques (laparoscopy, single access laparoscopy, flexure mobilization, ileostomy creation, mesenteric artery ligation, and transvaginal extraction), operative time was significantly longer only in cases of flexure mobilization (β = 0.3, P = 0.01). Although time to flatus was similar in both complicated and uncomplicated cases (36.1 ± 18.2 h vs 29.6 ± 17 h, P = 0.13), the length of hospital stay was statistically shorter in uncomplicated cases (7.9 ± 3.1 in complicated vs 6.4 ± 1.5 in uncomplicated cases, P < 0.001).

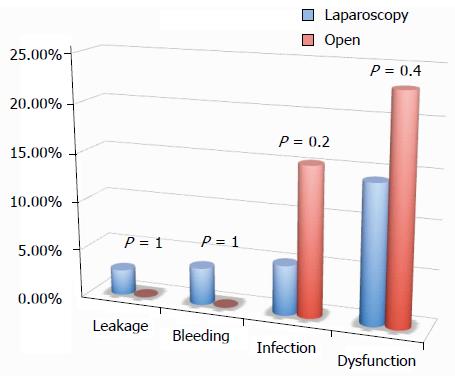

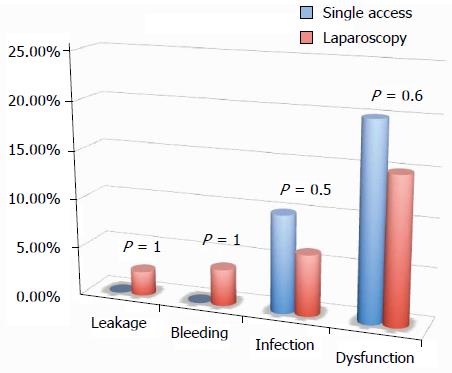

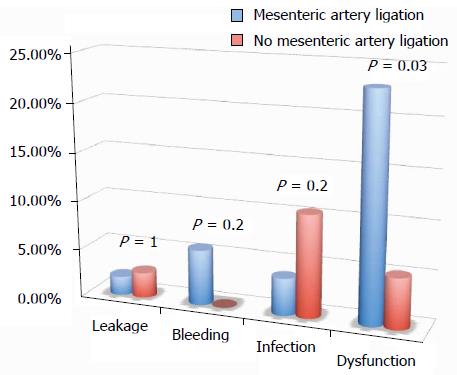

All of the different surgical techniques are summarized in Table 2. We registered a similar number of complicated cases. A multivariate regression analysis (stepwise method) showed that, after adjusting for major clinical, demographic, and surgical characteristics, complicated cases were associated only with endometriosis localization from the anal verge (OR = 0.8, 95%CI: 0.74-0.98, P = 0.03). Interestingly, analysis of the association between post-operative complications and each different surgical technique (Figures 1, 2, 3 and 4) revealed that only bowel dysfunction after surgery was associated with mesenteric artery ligation (11 out of 44 dysfunctions in the mesenteric artery ligation group vs 2 out of 36 cases in the no mesenteric artery ligation group, P = 0.03). However, a trend toward less infection and dysfunction was obtained after laparoscopic surgery (infection: 5% in the laparoscopic group vs 15% in the open group; dysfunction: 14% in the laparoscopic group vs 23% in the open group). Similarly, a trend toward more bleeding was obtained after flexure mobilization (5% in the flexure mobilization group vs 0% in the no flexure mobilization group). Finally, a trend toward more bleeding was observed after mesenteric artery ligation (6% in the mesenteric ligation group vs 0% in the no mesenteric ligation group).

| Complicated cases (22) | Uncomplicated cases (68) | P value | |

| Laparoscopy | 19 (86.3) | 58 (85.2) | 0.73 |

| Single access laparoscopy | 3 (13.6) | 7 (10.2) | 0.71 |

| Ileostomy | 4 (18.1) | 18 (26.4) | 0.41 |

| Flexure mobilization | 15 (68.1) | 46 (67.6) | 0.79 |

| Mesenteric artery ligation | 16 (72.7) | 36 (52.9) | 0.22 |

| Transvaginal extraction | 7 (31.8) | 15 (22) | 0.57 |

Interestingly, the incidence of leakage was very low (2.2%), and the negative predictive value (those without leakage and without diverting ileostomy/those without leakage either with or without diverting ileostomy) of having a leakage in the absence of diverting ileostomy was quite high (97%). Similarly, no leakage occurred after single access laparoscopy.

Deep endometriosis invading the bowel constitutes a major challenge for gynecologists. In addition to a greater impact on pain[13,14], the high incidence of surgical morbidity involved with the bowel[2,15,16] poses a therapeutic dilemma for the surgeon[17,18]. Intestinal involvement of deep endometriotic nodules has been estimated to occur in 8%-12% of women with endometriosis[19,20], with colorectal disease involvement representing almost 90% of these cases[4,7,21-23]. The complete excision of all endometriotic lesions is the main objective of both laparoscopic and laparotomic surgeries that require a multidisciplinary approach[24,25] and highly skilled surgeons. Laparoscopic excision of deep infiltrating bowel endometriosis has become a frequently used treatment modality, and segmental bowel resection has been performed in many cases, despite the relatively high morbidity rate.

Both major and minor surgical complications have been reported after the excision of deep endometriosis involving the bowel, including fistula (0%-14%)[25-27], hemorrhage (1%-11%)[19,28], infection (1%-3%)[27,29], laparoconversion (up to 12%), and bladder (1%-71%) and bowel (1%-15%)[27,30,31] dysfunction such as post-operative severe constipation[32].

Brouwer and Woods[33] reported that the type of surgical approach, including full-thickness excision of the rectal wall and segmental resection, does not change the rate of complications. However, many factors are affected by the surgeon’s learning curve, such as the conversion rate, operating time, complication rate, and surgical effectiveness[34]. Nevertheless, complications can occur, even among experienced surgeons[35]. Accordingly, only procedures performed by expert surgeons were included in our analysis.

There are three frequently observed risk factors for major complications: opening of the vagina at the time of the bowel surgical procedure[36], excessive use of electrocoagulation that may increase the risk of rectovaginal fistulae and abscesses (potentially leading to necrosis of the posterior vaginal cuff)[30], and surgical treatment of low rectal lesions (< 5-8 cm from the anal verge), which increases the risk of anastomotic leaks[28,37].

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the impact of different surgical techniques on the occurrence of post-operative complications. We have evaluated the potential influence of the most relevant surgical differences, including laparoscopic approach, single access laparoscopy, flexure mobilization, mesenteric artery ligation, specimen extraction site, and diverting ileostomy creation.

Interestingly, we found that the occurrence of post-operative complications was not influenced by surgical technique. Only mesenteric artery ligation was associated with a higher incidence of bowel dysfunction after surgery (P = 0.03). Thus, based on current knowledge, this study confirms that preservation of the inferior mesenteric artery should be recommended to reduce the incidence of defecatory disorders after left hemicolectomy for benign disease[38]. The sectioning of sigmoid arteries close to the colonic wall without sectioning the inferior mesenteric artery may preserve innervations of the neosigmoid and could reduce defecatory disorders.

As the incidence of leakage was very low (2.2%), we cannot justify the routine use of diverting ileostomy. Similarly, the negative predictive value (probability of leakage in the absence of diverting ileostomy) was quite high (97%), and thus we can exclude the need for diverting ileostomy.

Furthermore, the absence of a higher incidence of post-operative complications after single access laparoscopy encourages this approach’s introduction in daily practice.

Finally, in contrast with previous publications, we did not find any association between the opening of the vagina and the occurrence of post-operative complications. This could be related to cooperation between the surgeon and the gynecologist.

Some limitations of this study must be addressed. The most major limitation lies in the study design; because this study was an evaluation of a prospective maintained database, there was a lack of patient randomization. However, multivariate analyses including all patients’ characteristics were performed to adjust the results for all other variables. Furthermore, although the surgical approach was dependent on the clinical advice of each individual surgeon, a propensity score was calculated to exclude any bias. Although a relatively small sample size was obtained in this multicenter study, certain biases were excluded, as only procedures performed by expert surgeons in standardized surgical indications with standard post-operative management were included.

Thus, our results encourage the consideration of laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis owing to its feasibility, safety, and low occurrence of post-operative complications, if performed by experienced surgeons. Furthermore, we cannot identify any surgical technique or approach that should be avoided to reduce major complications after surgery.

This study clearly provides the rationale for a future randomized clinical trial comparing different surgical approaches in order to provide a definitive conclusion.

Although laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection is an established technique for the treatment of colorectal endometriosis, little is known about the impact of different surgical techniques on post-operative complications.

The results encourage the consideration of laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis owing to its feasibility, safety, and low incidence of post-operative complications, if performed by experienced surgeons. Furthermore, we cannot identify any surgical technique or approach that should be avoided to reduce major complications after surgery.

This study clearly provides the rationale for a future randomized clinical trial comparing different surgical approaches in order to provide a definitive conclusion.

This paper is well constructed, with good data and statistical analysis. Further randomized clinical trials are needed to give more a definitive conclusion.

P- Reviewer: La Torre F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Rutherford A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Emmanuel KR, Davis C. Outcomes and treatment options in rectovaginal endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2005;17:399-402. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Ruffo G, Sartori A, Crippa S, Partelli S, Barugola G, Manzoni A, Steinasserer M, Minelli L, Falconi M. Laparoscopic rectal resection for severe endometriosis of the mid and low rectum: technique and operative results. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:1035-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Daraï E, Bazot M, Rouzier R, Houry S, Dubernard G. Outcome of laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2007;19:308-313. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Bailey HR, Ott MT, Hartendorp P. Aggressive surgical management for advanced colorectal endometriosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:747-753. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Azioni G, Bracale U, Scala A, Capobianco F, Barone M, Rosati M, Pignata G. Laparoscopic ureteroneocystostomy and vesicopsoas hitch for infiltrative ureteral endometriosis. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2010;19:292-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Jerby BL, Kessler H, Falcone T, Milsom JW. Laparoscopic management of colorectal endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:1125-1128. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Remorgida V, Ferrero S, Fulcheri E, Ragni N, Martin DC. Bowel endometriosis: presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:461-470. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Fanfani F, Fagotti A, Gagliardi ML, Ruffo G, Ceccaroni M, Scambia G, Minelli L. Discoid or segmental rectosigmoid resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: a case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2010;94:444-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kamergorodsky G, Lemos N, Rodrigues FC, Asanuma FY, D’Amora P, Schor E, Girão MJ. Evaluation of pre- and post-operative symptoms in patients submitted to linear stapler nodulectomy due to anterior rectal wall endometriosis. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2389-2393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Milone M, Elmore U, Di Salvo E, Delrio P, Bucci L, Ferulano GP, Napolitano C, Angiolini MR, Bracale U, Clemente M. Intracorporeal versus extracorporeal anastomosis. Results from a multicentre comparative study on 512 right-sided colorectal cancers. Surg Endosc. 2015;29:2314-2320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Milone M, Mollo A, Musella M, Maietta P, Sosa Fernandez LM, Shatalova O, Conforti A, Barone G, De Placido G, Milone F. Role of colonoscopy in the diagnostic work-up of bowel endometriosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4997-5001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fauconnier A, Fritel X, Chapron C. [Endometriosis and pelvic pain: epidemiological evidence of the relationship and implications]. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2009;37:57-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jacobson TZ, Duffy JM, Barlow D, Koninckx PR, Garry R. Laparoscopic surgery for pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD001300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3573] [Cited by in RCA: 2754] [Article Influence: 1377.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Vercellini P, Crosignani PG, Abbiati A, Somigliana E, Viganò P, Fedele L. The effect of surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: the other side of the story. Hum Reprod Update. 2009;15:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Roman H, Vassilieff M, Gourcerol G, Savoye G, Leroi AM, Marpeau L, Michot F, Tuech JJ. Surgical management of deep infiltrating endometriosis of the rectum: pleading for a symptom-guided approach. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:274-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chapron C, Chopin N, Borghese B, Malartic C, Decuypere F, Foulot H. Surgical management of deeply infiltrating endometriosis: an update. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1034:326-337. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Abrao MS, Gonçalves MO, Dias JA, Podgaec S, Chamie LP, Blasbalg R. Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:3092-3097. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Seracchioli R, Poggioli G, Pierangeli F, Manuzzi L, Gualerzi B, Savelli L, Remorgida V, Mabrouk M, Venturoli S. Surgical outcome and long-term follow up after laparoscopic rectosigmoid resection in women with deep infiltrating endometriosis. BJOG. 2007;114:889-895. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wills HJ, Reid GD, Cooper MJ, Morgan M. Fertility and pain outcomes following laparoscopic segmental bowel resection for colorectal endometriosis: a review. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:292-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Coronado C, Franklin RR, Lotze EC, Bailey HR, Valdés CT. Surgical treatment of symptomatic colorectal endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:411-416. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Tran KT, Kuijpers HC, Willemsen WN, Bulten H. Surgical treatment of symptomatic rectosigmoid endometriosis. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:139-141. [PubMed] |

| 23. | De Cicco C, Corona R, Schonman R, Mailova K, Ussia A, Koninckx P. Bowel resection for deep endometriosis: a systematic review. BJOG. 2011;118:285-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Possover M, Diebolder H, Plaul K, Schneider A. Laparascopically assisted vaginal resection of rectovaginal endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:304-307. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Keckstein J, Wiesinger H. Deep endometriosis, including intestinal involvement--the interdisciplinary approach. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2005;14:160-166. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Duepree HJ, Senagore AJ, Delaney CP, Marcello PW, Brady KM, Falcone T. Laparoscopic resection of deep pelvic endometriosis with rectosigmoid involvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;195:754-758. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Ruffo G, Scopelliti F, Scioscia M, Ceccaroni M, Mainardi P, Minelli L. Laparoscopic colorectal resection for deep infiltrating endometriosis: analysis of 436 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:63-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Darai E, Ackerman G, Bazot M, Rouzier R, Dubernard G. Laparoscopic segmental colorectal resection for endometriosis: limits and complications. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1572-1577. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Meuleman C, D’Hoore A, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Beks N, D’Hooghe T. Outcome after multidisciplinary CO2 laser laparoscopic excision of deep infiltrating colorectal endometriosis. Reprod Biomed Online. 2009;18:282-289. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Dubernard G, Piketty M, Rouzier R, Houry S, Bazot M, Darai E. Quality of life after laparoscopic colorectal resection for endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:1243-1247. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Mangler M, Loddenkemper C, Lanowska M, Bartley J, Schneider A, Köhler C. Histopathology-based combined surgical approach to rectovaginal endometriosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;103:59-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Armengol-Debeir L, Savoye G, Leroi AM, Gourcerol G, Savoye-Collet C, Tuech JJ, Vassilieff M, Roman H. Pathophysiological approach to bowel dysfunction after segmental colorectal resection for deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: a preliminary study. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2330-2335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Brouwer R, Woods RJ. Rectal endometriosis: results of radical excision and review of published work. ANZ J Surg. 2007;77:562-571. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Carmona F, Martínez-Zamora A, González X, Ginés A, Buñesch L, Balasch J. Does the learning curve of conservative laparoscopic surgery in women with rectovaginal endometriosis impair the recurrence rate? Fertil Steril. 2009;92:868-875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Haggag H, Solomayer E, Juhasz-Böss I. The treatment of rectal endometriosis and the role of laparoscopic surgery. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2011;23:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D’Hoore A, Van Cleynenbreugel B, Penninckx F, Vergote I, D’Hooghe T. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Hum Reprod Update. 2011;17:311-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Trencheva K, Morrissey KP, Wells M, Mancuso CA, Lee SW, Sonoda T, Michelassi F, Charlson ME, Milsom JW. Identifying important predictors for anastomotic leak after colon and rectal resection: prospective study on 616 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257:108-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Masoni L, Mari FS, Nigri G, Favi F, Gasparrini M, Dall’Oglio A, Pindozzi F, Pancaldi A, Brescia A. Preservation of the inferior mesenteric artery via laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy performed for diverticular disease: real benefit or technical challenge: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:199-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |