Published online Dec 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13325

Peer-review started: May 15, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: July 28, 2015

Accepted: October 12, 2015

Article in press: October 13, 2015

Published online: December 21, 2015

Processing time: 214 Days and 13.8 Hours

AIM: To analyze the relationship between lymph node metastasis and clinical pathology of early gastric cancer (EGC) in order to provide criteria for a feasible endoscopic therapy.

METHODS: Clinical data of the 525 EGC patients who underwent surgical operations between January 2009 and March 2014 in the West China Hospital of Sichuan University were analyzed retrospectively. Clinical pathological features were compared between different EGC patients with or without lymph node metastasis, and investigated by univariate and multivariate analyses for possible relationships with lymph node metastasis.

RESULTS: Of the 2913 patients who underwent gastrectomy with lymph node dissection, 529 cases were pathologically proven to be EGC and 525 cases were enrolled in this study, excluding 4 cases of gastric stump carcinoma. Among 233 patients with mucosal carcinoma, 43 (18.5%) had lymph node metastasis. Among 292 patients with submucosal carcinoma, 118 (40.4%) had lymph nodemetastasis. Univariate analysis showed that gender, tumor size, invasion depth, differentiation type and lymphatic involvement correlated with a high risk of lymph node metastasis. Multivariate analysis revealed that gender (OR = 1.649, 95%CI: 1.091-2.492, P = 0.018), tumor size (OR = 1.803, 95%CI: 1.201-2.706, P = 0.004), invasion depth (OR = 2.566, 95%CI: 1.671-3.941, P = 0.000), histological differentiation (OR = 2.621, 95%CI: 1.624-4.230, P = 0.000) and lymphatic involvement (OR = 3.505, 95%CI: 1.590-7.725, P = 0.002) were independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis. Comprehensive analysis showed that lymph node metastasis was absent in patients with tumor that was limited to the mucosa, size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and without lymphatic involvement.

CONCLUSION: We propose an endoscopic therapy for EGC that is limited to the mucosa, size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and without lymphatic involvement.

Core tip: Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as invasive gastric cancer that invades no more deeply than the submucosa, irrespective of lymph node metastasis. Gastrectomy/endoscopic resection can be used for the treatment of patients meeting appropriate criteria. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated the relationship between lymph node metastasis and clinical pathological features of 525 EGC cases. Univariate and multivariate analyses were applied to confirm the risk factors for lymph node metastasis, and to establish indications for a feasible individualized endoscopic therapy for EGC.

- Citation: Guo TJ, Qin JY, Zhu LL, Wang J, Yang JL, Wang YP. Feasible endoscopic therapy for early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(47): 13325-13331

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i47/13325.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i47.13325

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined by the Japanese Society of Gastroenterological Endoscopy as invasive gastric adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of lymph node metastasis (T1, any N)[1]. Worldwide, gastrectomy remains the most widely used approach for the treatment of EGC, and the 5-year survival rate of patients who undergo curative surgery exceeds 90%[2]. Hence, it is important to detect and treat the cancer at early stage. In recent years, with the constant development of new endoscopy technology, such as chromoendoscopy, magnifying endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and the improvement of endoscopic diagnosis, more and more EGC are detected and accurately diagnosed[3]. Approximately 50% of gastric cancer cases currently found in Japan ar eat early stage, while in China, less than 10% of EGC is diagnosed[4]. The percentage has been gradually improving recently[5]. Meanwhile, minimally invasive techniques, especially endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for EGC, have dramatically grown. Compared with traditional radical surgical procedure, endoscopic treatment has many unique features, including being equally effective, less invasive, and having fewer complications and faster postoperative recovery, which make it possibly a better option for EGC patients[6,7]. For EGC with lymph node metastasis, however, EMR and ESD are not ideal since they are unable to remove lymph nodes and thus achieve a radical cure effect. So accurate judgment of lymph node metastasis in patients with EGC is very important for the selection of appropriate therapy and prognosis of patients[8]. This study retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of 525 patients with EGC who underwent gastrectomy with lymph node dissection in our hospital over the last five years. The purpose is to evaluate the relationship between lymph node metastasis and clinical pathological features of EGC, and to propose criteria for feasible individualized endoscopic therapy.

We collected 2913 cases of patients who underwent gastrectomy with lymph node dissection at West China Hospital of Sichuan University between January 2009 and March 2014. Of these, 529 cases were pathologically proven to be EGCs. A total of 525 cases were enrolled in this study, excluding 4 cases of gastric stump carcinoma. Patient characteristics, including age and gender, were collected. In addition, information on tumor size, histological type, invasion depth, ulceration and lymphatic invasion was also retrieved from medical records.

According to the 7th edition of Tumor-Node-Metastasis stage criteria by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, we subdivided EGC into: T1a-invasion of lamina propria or muscularis mucosae; T1b-invasion of submucosa[9]. The depth of tumor invasion was classified as mucosa (T1a) and submucosa carcinoma (T1b). The maximum diameter of tumor was recorded as tumor size according to the operation records and pathologic description. Tumor histology was classified into two groups according to Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: the differentiated group, which included papillary adenocarcinoma and well or moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma; and the undifferentiated group, which included poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, mucinous, and signet ring cell carcinoma[10]. Associations between lymph node metastasis and clinical pathological features were assessed by univariate (Table 1) and multivariate (Table 2) analyses, and the lymph node metastasis status of T1a tumors according to gender, tumor size, histological differentiation and lymphatic involvement was analyzed (Table 3).

| Variables | Lymph node metastasis | P value | |

| Negative(n = 364) | Positive(n = 161) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 241 (73.5) | 87 (26.5) | 0.008 |

| Female | 123 (62.4) | 74 (37.6) | |

| Age (yr) | |||

| < 60 | 207 (67.2) | 101 (32.8) | 0.208 |

| ≥ 60 | 157 (72.4) | 60 (27.6) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | |||

| ≤ 2 | 202 (76.5) | 62 (23.5) | 0.000 |

| > 2 | 162 (62.1) | 99 (37.9) | |

| Invasion depth | |||

| Mucosa (T1a) | 190 (81.5) | 43 (18.5) | 0.000 |

| Submucosa (T1b) | 174 (59.6) | 118 (40.4) | |

| Histology | |||

| Differentiated | 144 (80.9) | 34 (19.1) | 0.000 |

| Undifferentiated | 220 (63.4) | 127 (36.6) | |

| Ulceration | |||

| Present | 79 (65.8) | 41 (34.2) | 0.344 |

| Absent | 285 (70.4) | 120 (29.6) | |

| Lymphatic involvement | |||

| Present | 11 (33.3) | 22 (66.7) | 0.000 |

| Absent | 353 (71.7) | 139 (28.3) | |

| Variables | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Gender (female/male) | 1.649 | 1.091-2.492 | 0.018 |

| Tumor size (> 2 cm/ ≤ 2 cm) | 1.803 | 1.201-2.706 | 0.004 |

| Invasion depth (T1b/T1a) | 2.566 | 1.671-3.941 | 0.000 |

| Histology (undifferentiated/differentiated) | 2.621 | 1.624-4.230 | 0.000 |

| Lymphaticinvolvement (present/absent) | 3.505 | 1.590-7.725 | 0.002 |

| Gender | Tumor size (cm) | Lymphatic involvement | Histology | Lymph node metastasis | |

| Negative | Positive | ||||

| Female (93) | ≤ 2 | Absent | Differentiated | 14 | 0 (0) |

| Undifferentiated | 32 | 8 (20) | |||

| Present | Differentiated | 0 | 1 (100) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | |||

| > 2 | Absent | Differentiated | 5 | 1 (16.7) | |

| Undifferentiated | 17 | 15 (46.9) | |||

| Present | Differentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | |||

| Male (140) | ≤ 2 | Absent | Differentiated | 36 | 0 (0) |

| Undifferentiated | 31 | 9 (22.5) | |||

| Present | Differentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 1 | 1 (50) | |||

| > 2 | Absent | Differentiated | 28 | 2 (6.7) | |

| Undifferentiated | 26 | 6 (18.75) | |||

| Present | Differentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 0 | 0 (0) | |||

All the data were analyzed with SPSS 22.0 statistics software (Chicago, IL, United States). Univariate analysis was performed by χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test when appropriate) to compare the clinicopathological factors between patients with and without lymph node metastasis. Significant factors noted by univariate analysis were subsequently entered into a multivariate logistic regression model to assess the independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis. OR and 95%CI were calculated, and statistical significance was established at P < 0.05.

Among the 525 patients with EGC, 161 (30.7%) were shown to have lymph node metastasis and 364 (69.3%) had no lymph node metastasis. This study included 233 mucosal carcinomas and 292 submucosal carcinomas. Among 233 patients with mucosal carcinoma, 43 (18.5%) had lymph node metastasis. Among 292 patients with submucosal carcinoma, 118 (40.4%) had lymph node metastasis. The relationship between lymph node metastasis and various clinicopathological factors was analyzed first by χ2 test (Table 1). Female gender (P = 0.008), tumor size > 2 cm (P = 0.000), invasion depth (submucosal invasion) (P = 0.000), undifferentiated histology (P = 0.000) and presence of lymphatic involvement (P = 0.000) were significantly associated with a higher rate of lymph node metastasis. In contrast, no significant relationship between lymph node metastasis and age or ulceration was found.

Using multivariate analysis, we found that all five risk factors identified above demonstrated significant correlation with lymph node metastasis. Specifically, female gender (OR = 1.649, 95%CI: 1.091-2.492, P = 0.018), tumor size > 2 cm (OR = 1.803, 95%CI: 1.201-2.706, P = 0.004), submucosal invasion (OR = 2.566, 95%CI: 1.671-3.941, P = 0.000), histological differentiation (OR = 2.621, 95%CI: 1.624-4.230, P = 0.000) and presence of lymphatic involvement (OR = 3.505, 95%CI: 1.590-7.725, P = 0.002) were found to be significantly and independently related to lymph node metastasis by multivariate logistic regression analysis (Table 2).

According to four independent factors including gender, tumor size, lymphatic involvement and histological differentiation, we analyzed 233 cases of T1a tumor.Table 3 shows that lymph node metastasis could not be found in patients with tumor that was limited to the mucosa, size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and without lymphatic involvement, irrespective of the gender.

For low risk of lymph node metastasis in EGC which has en bloc resection, EMR or ESD has become the first choice of treatment[5]. How to accurately predict lymph node metastasis of EGC in the early stage is the main problem, which determines whether ESD/EMR treatment can be chosen. Clinically, we usually use EUS, a combination of endoscopy and ultrasound to obtain images of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and adjacent structures[11], and/or spiral computed tomography (CT) as major screening methods for lymph node metastasis of EGC in preoperative assessment[12]. For the use of EUS in the preoperative determination of lymph node status in patients with gastric cancer can have a significant impact on patient management[13]. Although the specificity to predict lymph node metastasis is as high as 96.3%, the sensitivity of EUS is only 66.7%[14]. Moreover, the accuracy of EUS dependents on the diameter size of metastasis lymph nodes and the technique of operators[14]. The specificity and sensitivity of spiral CT in the diagnosis of lymph node metastasis are 65% and 75%, respectively[15]. Additionally, it is difficult to distinguish the metastasis lymph nodes from small normal lymph nodes by spiral CT, although it has certain clinical value for EGC[13]. As the supplement of EUS and spiral CT, clinical pathology is one of the effective methods to determine lymph node metastasis in EGC[16].

The reported rates of lymph node metastasis were 2.6%-4.8% for mucosal carcinoma and 16.5%-23.6% for submucosal carcinoma[17]. However, our data showed that the positive rates of lymph node metastasis in mucosal and submucosal lesions were 18.5% and 40.4%, respectively. This difference may be due to the limitations of our sample collection. We simply retrospectively analyzed radical surgery patients as the research subjects over the most recent five-year period. It should be noted that some EGC patients, who were judged without lymph node metastasis by EUS/spiral CT, received ESD/EMR treatment instead of surgery. These patients were excluded from our study, which might lead to the high positive rates of lymph node metastasis.

Many studies have evaluated the risk of lymph node metastasis in gastric cancer. For example, Lim et al[8] found that tumor size, invasion depth and lymphatic involvement were closely related to lymph node metastasis in EGC. In addition, Ye et al[18] and Abe et al[19] reported that histological differentiation and gender were independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis in EGC. Consistent with these reports, in our study involving 525 patients and univariate/multivariate analyses, we found that tumor size, invasion depth, lymphatic involvement, histological differentiation and gender were independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis.

Multivariate analysis found that the risk of lymph node metastasis in EGC patients differed according to tumor size and invasion depth: tumor size > 2 cm had 1.803 times (95%CI: 1.201-2.706) greater risk than tumor size ≤ 2 cm; submucosal carcinoma had 2.566 times (95%CI: 1.671-3.941) greater risk than mucosa carcinoma. These data are consistent with previous reports that tumor size and invasion depth are considered to be independent risk factors for lymph node metastasis[20,21]. Specifically, when the tumor is larger than 2 cm in diameter and infiltrates into the submucosa, the risk for lymph node metastasis increases significantly. It would be better to choose surgery instead of endoscopic therapy[22]. Multivariate analysis also found that the risk for lymph node metastasis was 3.505 times greater with lymphatic invasion. Liu et al[23] and Nakamura et al[24] analyzed 188 cases and 73 cases of EGC respectively, and reported that lymphatic involvement was an independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis in EGC, which was consistent with our conclusion.

We found that histological differentiation was significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis. Undifferentiated EGC had a much higher risk than differentiated EGC in lymph node metastasis. Ye et al[18] previously reported the same conclusion. It should be noted, however, that there has been evidence showing no correlation between histological differentiation and lymph node metastasis for EGC[19,25]. Gotoda et al[26] divided 5265 cases of EGC into mucosal carcinoma and submucosal carcinoma, and analyzed them retrospectively. They reported that lymph node metastasis in mucosal carcinoma was associated with histological differentiation, while there was no clear relationship between lymph node metastasis in submucosal carcinoma and histological differentiation.

We also showed that gender was associated with lymph node metastasis. Females were more likely to have lymph node metastasis than males. This finding was consistent with previous reports that the growth of tumor results from the estrogen produced by women[27,28]. However, the specific biological mechanism remains unclear. Therefore, the specific link between gender and lymph node metastasis for EGC needs to be further examined.

After further analysis of 233 T1a carcinomas based on four independent factors including gender, tumor size, lymphatic involvement and histological differentiation, we propose an endoscopic therapy for T1a carcinoma that is limited to tumor size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and without lymphatic involvement. In the latest edition of Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines, the indications for endoscopic treatment of T1a carcinoma are: tumor size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and no ulcer[29]. Different from the guidelines, we consider “no lymphatic involvement” rather than “no ulcer” as an indication for endoscopic treatment. Consistent with the reports from Park et al[25] and Sung et al[30], our study revealed that ulceration was not an independent risk factor for lymph node metastasis in EGC. Additionally, ulceration is mainly judged by endoscopy and pathology examinations; both have certain subjective bias. If patients had previously undergone mucosa biopsy, it would be quite difficult to identify primary ulcers from biopsy injuries under the endoscope[31]. So it is difficult to judge precisely whether there are ulcers or not in clinical practice. In addition, gastritis profunda cystica has been alongside EGC and mimicked cancer[32].

In recent years, lymphatic involvement is considered to be the most powerful factor for the prediction of lymph node metastasis in EGC[33,34]. However, there are no effective methods to estimate lymphatic involvement preoperatively. Only through pathologic examination of resection specimens after surgery or endoscopic resection can we identify lymphatic involvement. Therefore, once postoperative specimens of EMR/ESD indicate lymphatic invasion, we should undertake additional surgical procedures as soon as possible, even for T1a patients[34].

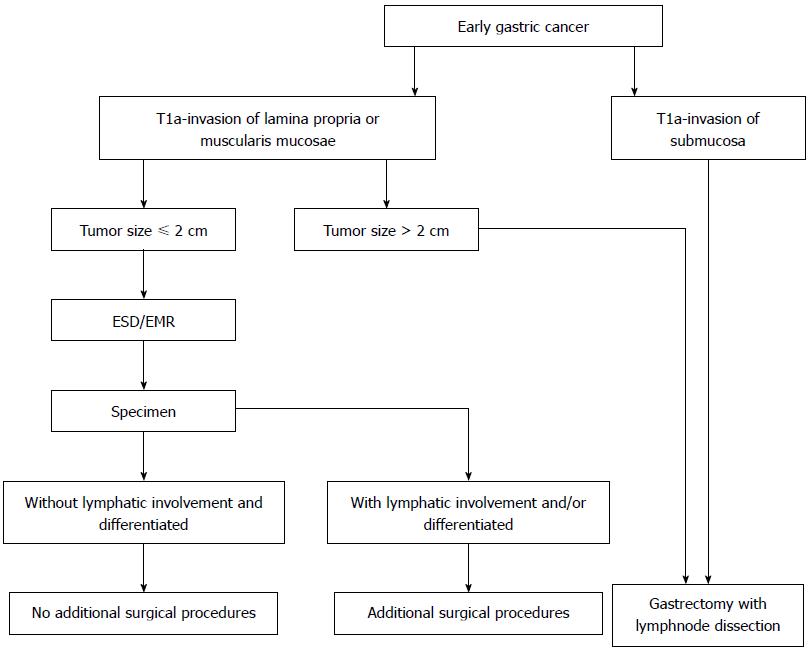

In summary, gender, tumor size, invasion depth, histology and lymphatic involvement are significantly correlated with lymph node metastasis. Further studies on the specific links between gender and lymph node metastasis are still needed. Patients with EGC that is limited to the mucosa, tumor size ≤ 2 cm, differentiated and without lymphatic involvement, have low risk for lymph node metastasis. For this kind of EGC, endoscopic therapy, which is safe and as effective as surgery, is proposed and recommended (Figure 1).

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is defined as invasive gastric cancer that invades no more deeply than the submucosa, irrespective of lymph node metastasis. Treatment modalities for EGC include endoscopic resection, surgery (gastrectomy) and adjuvant therapies. Endoscopic resection, by either endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), is an option for selected patients with EGC without known lymph node metastasis who meet specific criteria. This study analyzed the predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in EGC, and established an indication for endoscopic treatment for EGC.

Several studies have attempted to identify risk factors predictive of lymph node metastasis in EGC. Few reports, however, have proposed criteria for endoscopic resection for EGC.

Guidelines for endoscopic therapy remain uncertain in areas outside of Japan and Korea. The authors analyzed clinical pathology of lymph node metastasis in EGC and established a criterion of endoscopic therapy for EGC.

Endoscopic resection could be an alternative treatment in EGC patients without risk factors for lymph node metastasis.

Endoscopic resection (ER) is an endoscopic alternative to surgical resection of mucosal and submucosal neoplastic lesions and intramucosal cancers; EMR: An ER technique providing a minimally invasive treatment for removal of superficial malignancies; ESD: An ER technique using a specialized needle-knife to dissect lesions from the submucosa, which offers the potential to remove mucosal and submucosal tumors en bloc.

This study analyzed the relationship between lymph node metastasis and clinical pathology of 525 EGC patients who underwent surgical operations. This is a good study about endoscopic therapy for EGC.

P- Reviewer: Chorny M, Pasricha PJ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Kunisaki C, Akiyama H, Nomura M, Matsuda G, Otsuka Y, Ono H, Nagahori Y, Hosoi H, Takahashi M, Kito F. Significance of long-term follow-up of early gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:363-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Choi JH, Kim ES, Lee YJ, Cho KB, Park KS, Jang BK, Chung WJ, Hwang JS, Ryu SW. Comparison of quality of life and worry of cancer recurrence between endoscopic and surgical treatment for early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hamashima C, Shibuya D, Yamazaki H, Inoue K, Fukao A, Saito H, Sobue T. The Japanese guidelines for gastric cancer screening. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:259-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 294] [Cited by in RCA: 275] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nomura S, Kaminishi M. Surgical treatment of early gastric cancer. Dig Surg. 2007;24:96-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yada T, Yokoi C, Uemura N. The current state of diagnosis and treatment for early gastric cancer. Diagn Ther Endosc. 2013;2013:241320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490-4498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 408] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Choi KS, Jung HY, Choi KD, Lee GH, Song HJ, Kim do H, Lee JH, Kim MY, Kim BS, Oh ST. EMR versus gastrectomy for intramucosal gastric cancer: comparison of long-term outcomes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:942-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lim MS, Lee HW, Im H, Kim BS, Lee MY, Jeon JY, Yang DH, Lee BH. Predictable factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer-analysis of single institutional experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1783-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Washington K. 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual: stomach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:3077-3079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 702] [Cited by in RCA: 814] [Article Influence: 58.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ge N, Sun S. Endoscopic ultrasound: An all in one technique vibrates virtually around the whole internal medical field. J Transl Intern Med. 2014;2:104-106. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ren G, Zhao JX, Cai R, Qi TY. Value of contrast-enhanced multiphasic spiral CT in detection of early gastric cancer and clinicopathologic features of early gastric cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi. 2015;23:110. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sharma M, Rai P, Rameshbabu CS. Techniques of imaging of nodal stations of gastric cancer by endoscopic ultrasound. Endosc Ultrasound. 2014;3:179-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yan C, Zhu ZG, Zhu Q, Yan M, Chen J, Liu BY, Yin HR, Lin YZ. [A preliminary study of endoscopic ultrasonography in the preoperative staging of early gastric carcinoma]. Zhonghua Zhongliu Zazhi. 2003;25:390-393. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Habermann CR, Weiss F, Riecken R, Honarpisheh H, Bohnacker S, Staedtler C, Dieckmann C, Schoder V, Adam G. Preoperative staging of gastric adenocarcinoma: comparison of helical CT and endoscopic US. Radiology. 2004;230:465-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Barreto SG, Windsor JA. Redefining early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2015;Epub ahead of print. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen R, He Q, Cui J, Bian S, Chen L. Lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127:560-567. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ye BD, Kim SG, Lee JY, Kim JS, Yang HK, Kim WH, Jung HC, Lee KU, Song IS. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis and endoscopic treatment strategies for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:46-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Abe N, Watanabe T, Suzuki K, Machida H, Toda H, Nakaya Y, Masaki T, Mori T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Risk factors predictive of lymph node metastasis in depressed early gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2002;183:168-172. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kunisaki C, Takahashi M, Nagahori Y, Fukushima T, Makino H, Takagawa R, Kosaka T, Ono HA, Akiyama H, Moriwaki Y. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in histologically poorly differentiated type early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2009;41:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ren G, Cai R, Zhang WJ, Ou JM, Jin YN, Li WH. Prediction of risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:3096-3107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Yoon SO, Kim H, Youn YH, Park H, Lee SI, Choi SH, Noh SH. Additive lymph node dissection may be necessary in minute submucosal cancer of the stomach after endoscopic resection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:779-785. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Liu C, Zhang R, Lu Y, Li H, Lu P, Yao F, Jin F, Xu H, Wang S, Chen J. Prognostic role of lymphatic vessel invasion in early gastric cancer: a retrospective study of 188 cases. Surg Oncol. 2010;19:4-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nakamura Y, Yasuoka H, Tsujimoto M, Kurozumi K, Nakahara M, Nakao K, Kakudo K. Importance of lymph vessels in gastric cancer: a prognostic indicator in general and a predictor for lymph node metastasis in early stage cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:77-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Park YD, Chung YJ, Chung HY, Yu W, Bae HI, Jeon SW, Cho CM, Tak WY, Kweon YO. Factors related to lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic mucosal resection for treating poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Endoscopy. 2008;40:7-10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lee JH, Choi MG, Min BH, Noh JH, Sohn TS, Bae JM, Kim S. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in patients with poorly differentiated early gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2012;99:1688-1692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Abe N, Sugiyama M, Masaki T, Ueki H, Yanagida O, Mori T, Watanabe T, Atomi Y. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis of differentiated submucosally invasive gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:242-245. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Sano T, Aiko T. New Japanese classifications and treatment guidelines for gastric cancer: revision concepts and major revised points. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Sung CM, Hsu CM, Hsu JT, Yeh TS, Lin CJ, Chen TC, Su MY, Chiu CT. Predictive factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5252-5256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Haruta H, Hosoya Y, Sakuma K, Shibusawa H, Satoh K, Yamamoto H, Tanaka A, Niki T, Sugano K, Yasuda Y. Clinicopathological study of lymph-node metastasis in 1,389 patients with early gastric cancer: assessment of indications for endoscopic resection. J Dig Dis. 2008;9:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Butt MO, Luck NH, Hassan SM, Zaigham Abbas Z, Mubarak M. Gastritis profunda cystica presenting as gastric outlet obstruction and mimicking cancer: A case report. J Transl Intern Med. 2015;3:35-38. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kim H, Kim JH, Park JC, Lee YC, Noh SH, Kim H. Lymphovascular invasion is an important predictor of lymph node metastasis in endoscopically resected early gastric cancers. Oncol Rep. 2011;25:1589-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Park WY, Shin N, Kim JY, Jeon TY, Kim GH, Kim H, Park do Y. Pathologic definition and number of lymphovascular emboli: impact on lymph node metastasis in endoscopically resected early gastric cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2132-2138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |