Published online Dec 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i46.13195

Peer-review started: February 9, 2015

First decision: April 24, 2015

Revised: June 2, 2015

Accepted: August 28, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: December 14, 2015

Processing time: 305 Days and 20.9 Hours

Gastric neuroendocrine tumors are rare; however, the incidence has recently increased due to the increasing use of upper endoscopy. Neuroendocrine tumors arise from the excess proliferation of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells. The proliferative changes of enterochromaffin cells evolve through a hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence that is believed to underlie the pathogenesis of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Endoscopic resection is recommended as the initial treatment if the tumor is not in an advanced stage. However, there is no definite guideline for the treatment of recurrent gastric neuroendocrine tumors following endoscopic resection. Here, we report a rare case of gastric neuroendocrine tumors in a 56-year-old male who experienced two recurrences within 11 years after endoscopic resection. The patient finally underwent a total gastrectomy. The pathological features of the resected stomach exhibited the full hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence of the ECL cells in a single specimen.

Core tip: This rare case exhibited the full hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence of enterochromaffin-like cells in a single specimen. This case clarifies the pathogenesis of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. Furthermore, this case revealed that total gastrectomy is a treatment option for patients with recurrent neuroendocrine tumors following excision.

- Citation: Jung M, Kim JW, Jang JY, Chang YW, Park SH, Kim YH, Kim YW. Recurrent gastric neuroendocrine tumors treated with total gastrectomy. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(46): 13195-13200

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i46/13195.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i46.13195

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) arise from the excessive proliferation of enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells. Gastric NETs are rare but are being reported at an increasing rate due to the increased use of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). The incidence of gastric NETs has increased ten-fold in the last 35 years[1]. These tumors have been reported to represent less than 2% of all NETs and less than 1% of all stomach neoplasms, but more recent analyses have suggested that these values may actually be 10% or higher[2]. Endoscopic treatments, such as endoscopic resection, are recommended as initial treatments for gastric NETs when the lesions are small and limited in number and there is no lymphovascular invasion[3]. When gastric NET recurs after endoscopic treatment, surgical local resection or total gastrectomy should be considered[4].

However, there is a lack of studies of the natural disease course following treatments such as endoscopic treatment and local surgical resection of the stomach.

We report a rare case involving two recurrences of gastric NET within 11 years that arose from the hyperplasia-dysplasia of ECL cells that was ultimately treated with total gastrectomy.

In October 2003, a 45-year-old Korean male was admitted to our hospital presenting with periumbilical pain. He had several medical problems, including hypertension and diabetes mellitus. The medicines he was taking included metformin, gliclazide, lacidipine, moexipril, and aspirin. The patient was mildly ill-looking in appearance. His vital signs were stable. All of the laboratory results were within the normal ranges with the exception of an increased glucose level. An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed and revealed a diffuse and marked thickening of the stomach wall that was suspected to be Borrmann type IV advanced gastric cancer. He did not have any family history of cancer or stomach disease. Diagnostic EGD was performed and revealed mild atrophic gastritis and three 0.7-1 cm polypoid lesions in the mid body to high body. However, advanced gastric cancer was not suspected. Biopsy of the lesions demonstrated a grade 1 NET. The lesions were removed by endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR).

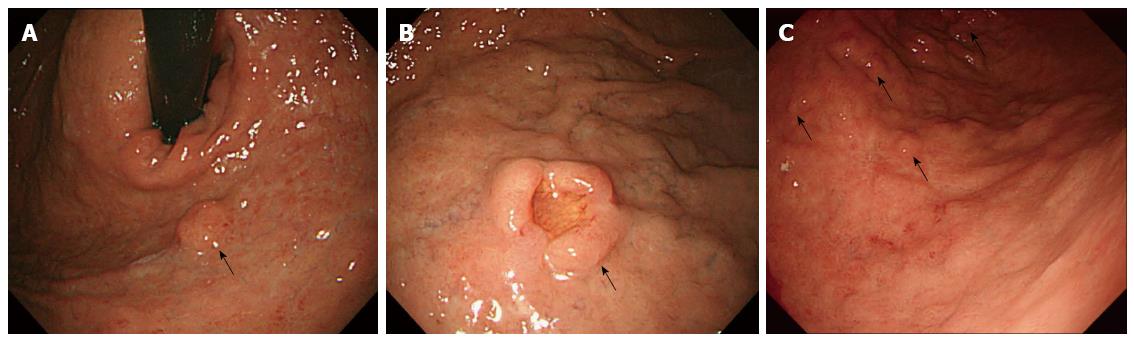

After EMR, annual EGDs revealed no recurrence of the gastric NET. However in 2010, two nodular lesions were detected. One of these lesions was in the cardia and approximately 1 cm in diameter (Figure 1A). The other lesion was a nodular lesion approximately 1.5 cm in diameter with central umbilication in the greater curvature side of the high body (Figure 1B). Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) indicated that the NETs were limited to the mucosa and submucosa. Because the tumors were large and had recurred, the patient underwent wedge resection of the stomach including the cardia and fundus and part of the high body. Histopathologically, the specimen exhibited submucosal proliferation of monotonous tumor cells with the formation of solid nests, glands and cords. The pathologist reported a diagnosis of grade 1 NET. The tumor in the fundus measured 1.2 cm in the greatest and the other tumor in the cardia measured 2.1 cm in the greatest dimension. The surgical margin was clear. After surgery, annual EGDs did not reveal any recurrence of the NET.

However in 2014, an EGD reveled four 0.5-1 cm reddish, elevated lesions located from the low body to the mid body (Figure 1C). Biopsies of the lesions revealed grade 1 NETs. An abdominal CT scan did not reveal any metastases to other organs. The urine 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (HIAA) level was 3.6 mg/d (normal range: 2-8 mg/d). An anti-intrinsic factor antibody test was negative, and an anti-parietal cell antibody test was also negative. The fasting gastrin level was within the normal range (65.4 pg/mL). There was no evidence of multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 (MEN-1). An abdominal CT and a brain and neck MRI revealed that the pituitary gland, parathyroid, and pancreas were normal. Due to the difficulty of removing all of the NET lesions and the patient’s concern over recurrence after endoscopic resection and wedge resection, we ultimately planned a total gastrectomy.

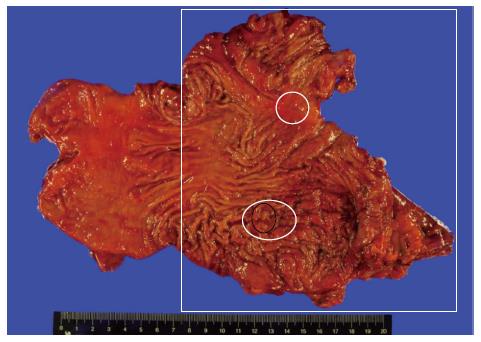

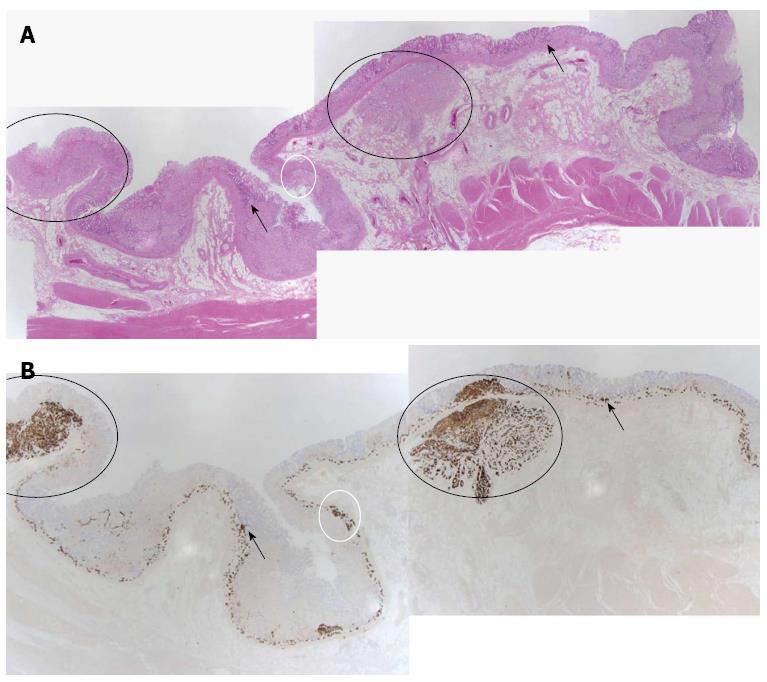

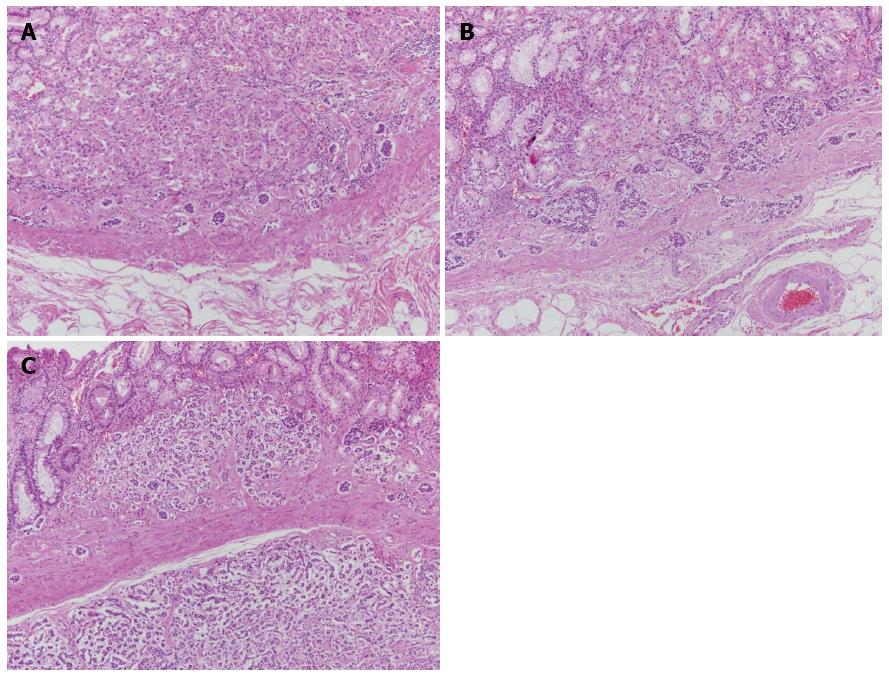

The patient underwent total gastrectomy. Macroscopically, the specimen exhibited multiple small nodules with erythematous changes located in the low body to the mid body (Figure 2). Histopathologically, the cluster of neuroendocrine cells exhibited wide-spectrum hyperplasia, dysplasia, and NET (Figure 3). The hyperplasia of neuroendocrine cells (Figure 4A) composed of five or more round and uniform cells arranged in a nodular cluster of less than 150 μm and infiltrated the lamina propria of the stomach. Dysplasias of the neuroendocrine cells between 150 and 500 μm in size were observed in the lamina propria of the stomach (Figure 4B). In the submucosa and lamina propria, the neuroendocrine cells were arranged in nests greater than 500 μm across that were indicative of NETs (Figure 4C). No mitosis of tumor cells was observed. Immunohistochemically, the specimen stained positively for chromogranin-A (CgA) and synaptophysin. The Ki-67 staining involved less than 1% of the specimen, which indicated that the tumor was a type 1 NET. In the resection margins, no tumors were identified, and no lymphatic or vascular invasion was observed. After surgery, the patient was discharged with full recovery. We did not observe any complications or recurrence within 9 mo after the surgery.

Gastric NET is usually called gastric carcinoid tumor and is a rare disease; however, the incidence of this condition has increased with the widespread use of EGD[5]. Gastric NET has four subgroups that are based on the clinicopathological features[6,7]. This patient was determined to have type I gastric NET because the tumors were small, multiple, and without metastasis. Additionally, the Ki-67 staining involved less than 1% of the tumors.

The definitive therapy for gastric NETs is the complete resection of the tumors[8]. Treatment depends on the sizes and numbers of tumors, the depth of invasion, and metastases to other organs. Endoscopic resection is recommended as the initial treatment for NETs, particularly for types I and II gastric NETs, when the tumor is less than 1 cm in size, there are fewer than 5 lesions, and there is no evidence of lymphovascular metastasis. If resection is not possible, minimally invasive surgeries, such as wedge resection, should be considered as alternative treatments. Antrectomy is also useful for suppressing the gastrin level in patients with type I gastric NETs[4]. Complete surgical resection increases the long-term survival of the patient[9]. However, there is another guideline that recommends annual surveillance for gastric NETs that are less than 1 cm because the risks of invasion or metastasis is low for such lesions[7,10]. This guideline also insists that surgery should be limited to cases involving invasion beyond the submucosa and metastases[10].

There is no definite guideline for the treatment of gastric NET, especially cases involving recurrence due to the low incidence of this condition and the lack of understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease. The European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) guidelines did not mention the management of recurrent gastric NETs[10]. Basuroy et al[7] vaguely recommended that tumors should be resected when possible. Crosby et al[4] insisted that in cases of NET recurrence after endoscopic resection, surgical resection, including wedge resection or antrectomy, is recommended. Total gastrectomy should be considered for the management of NET recurrence after minimally invasive surgery. Definite guidelines for the treatment of recurrent gastric NETs are needed, because recurrence occurs frequently in type 1 gastric NET cases. Merola et al[11] reported that 63.6% of type 1 gastric NET cases experience recurrence after a median of 8 mo, and 66.6% of these cases experience a second recurrence after a median of 8 mo following carcinoid removal.

In the present case, the patient ultimately underwent total gastrectomy. We failed to treat the gastric NET of this patient with endoscopic resection and surgical wedge resection. We did not consider antrectomy to be a treatment option because this patient’s gastrin level was normal. Furthermore, the patient was concerned about the two recurrences with multiple lesions that he had experienced over 11 years and the broad range of gastric NETs from the mid body to the high body. Therefore, we decided to perform a total gastrectomy for definite treatment. We recommend total gastrectomy as a treatment option for recurrent and multiple gastric NETs, particularly in cases with accompanying hyperplasia or dysplasia. We know that the prognosis for type 1 gastric NET is good even if the tumor is not definitely completely removed. However, there are some benefits of total gastrectomy that include the lack of a need for annual surveillance, the prevention of the progression to metastasis, and preventing the patient from worrying about recurrence.

We finally identified the reason for the recurrences over 11 years in the pathological findings of the resected stomach specimen. The pathology of this patient exhibited the entire hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence based on chronic gastritis. The hyperplasia of the neuroendocrine cells in the stomach of this patient had progressed to dysplasia and ultimately to NET over 11 years. Indeed, cases of chronic atrophic gastritis with known ECL-cell dysplasia are associated with a significantly higher risk of developing type 1 gastric NETs than are cases with nondysplastic changes; the incidences of recurrence for these conditions are 6.3 and 0.3 per 100 person-year, respectively (HR = 20.7)[12].

Therefore, physicians should consider random biopsies of multiple lesions in the stomach, particularly in cases of NET recurrence and cases in which hyperplasia has been found in previous biopsies. Biopsy specimens should be taken not only from the suspected gastric NET lesion but also from two nonlesion locations in the antrum and four in the body/fundus[7]. Subsequently, if the physicians find multiple hyperplastic or dysplastic lesions of the ECL cells with the NET, they should follow the patient more closely than they would patients without hyperplasia or dysplasia of the ECL cells. Additionally, pathologists should attempt to identify and report lesions with hyperplasia or dysplasia of the neuroendocrine cells in detail even if the patient has already had gastric NET lesions.

Oddly, the gastrin level of the present patient was normal. Gastrin stimulation has been demonstrated to play a critical role in the proliferative changes of ECL cells through the hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence[13]. Severe hyperplasia or dysplasia of the ECL cells with chronic atrophic gastritis confined to the fundus-body of the stomach are risk factors for the development of NET[12]. However, hypergastrinemia has been reported in only 50% of multiple gastric NET cases[14]. Furthermore, hypergastrinemia alone is not sufficient for the development of NET because some situations that generate hypergastrinemia, such as long-term proton pump inhibitor use and vagotomy, are not associated with gastric NET. Therefore, multiple factors, including genetic mutation, growth factors, bacterial infection, environment, diet, and hormones (e.g., gastrin and somatostatin), may be involved in the development of gastric NET[15].

In conclusion, we have reported a case with multiple gastric NETs that recurred over 11 years and were ultimately treated with total gastrectomy after repeated surgical and endoscopic excisions. This rare case exhibited the full hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence of ECL cells in a single specimen. This case clarifies the pathogenesis of this condition and validates total gastrectomy as a treatment option for patients with recurrent multifocal gastric NETs after local excision. In addition to this case report, additional studies to establish the pathogenesis and management of multiple recurrent gastric NETs after initial treatment are warranted.

Recurrent multifocal neuroendocrine tumor with hyperplasia and dysplasia of the neuroendocrine cells in a 45-year-old patient.

The patient had no symptom other than vague periumbilical pain.

The differential diagnoses included malignancy or hyperplastic polyps of stomach.

All of the laboratory results were within the normal ranges with the exception of an increased glucose level.

Several gastric 1-2 cm polyps were found on endoscopic assessment.

The pathological features of the resected stomach exhibited the full hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence of the enterochromaffin-like (ECL) cells in a single specimen of resected stomach.

The patient ultimately underwent total gastrectomy due to recurrence after treatment with endoscopic mucosal resection and gastric surgical wedge resection.

Physicians should attempt to diagnosis hyperplastic or dysplastic ECL cell lesions, particularly when gastric neuroendocrine tumors recur, and they should consider total gastrectomy as a treatment option.

This rare case exhibited the full hyperplasia-dysplasia-neoplasia sequence of ECL cells in a single specimen. Additionally, this case indicated that total gastrectomy is one treatment options for patients with recurrent neuroendocrine tumors especially when the tumors are accompanied by hyperplasia or dysplasia of the ECL cells.

P- Reviewer: Ohtsuka T, Zhao HD S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Scherübl H, Cadiot G, Jensen RT, Rösch T, Stölzel U, Klöppel G. Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (gastric carcinoids) are on the rise: small tumors, small problems? Endoscopy. 2010;42:664-671. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 50-year analysis of 562 gastric carcinoids: small tumor or larger problem? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:23-32. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Hoshino M, Omura N, Yano F, Tsuboi K, Matsumoto A, Yamamoto SR, Akimoto S, Kashiwagi H, Yanaga K. Usefulness of laparoscope-assisted antrectomy for gastric carcinoids with hypergastrinemia. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:379-382. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Crosby DA, Donohoe CL, Fitzgerald L, Muldoon C, Hayes B, O’Toole D, Reynolds JV. Gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Dig Surg. 2012;29:331-348. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Chen WF, Zhou PH, Li QL, Xu MD, Yao LQ. Clinical impact of endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric neuroendocrine tumors: a retrospective study from mainland China. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:869769. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Vannella L, Lahner E, Annibale B. Risk for gastric neoplasias in patients with chronic atrophic gastritis: a critical reappraisal. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1279-1285. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Basuroy R, Srirajaskanthan R, Prachalias A, Quaglia A, Ramage JK. Review article: the investigation and management of gastric neuroendocrine tumours. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1071-1084. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Li TT, Qiu F, Qian ZR, Wan J, Qi XK, Wu BY. Classification, clinicopathologic features and treatment of gastric neuroendocrine tumors. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:118-125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Ahlman H, Wängberg B, Jansson S, Friman S, Olausson M, Tylén U, Nilsson O. Interventional treatment of gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumours. Digestion. 2000;62 Suppl 1:59-68. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Delle Fave G, Kwekkeboom DJ, Van Cutsem E, Rindi G, Kos-Kudla B, Knigge U, Sasano H, Tomassetti P, Salazar R, Ruszniewski P. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with gastroduodenal neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:74-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Merola E, Sbrozzi-Vanni A, Panzuto F, D’Ambra G, Di Giulio E, Pilozzi E, Capurso G, Lahner E, Bordi C, Annibale B. Type I gastric carcinoids: a prospective study on endoscopic management and recurrence rate. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:207-213. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Vanoli A, La Rosa S, Luinetti O, Klersy C, Manca R, Alvisi C, Rossi S, Trespi E, Zangrandi A, Sessa F. Histologic changes in type A chronic atrophic gastritis indicating increased risk of neuroendocrine tumor development: the predictive role of dysplastic and severely hyperplastic enterochromaffin-like cell lesions. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:1827-1837. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Solcia E, Bordi C, Creutzfeldt W, Dayal Y, Dayan AD, Falkmer S, Grimelius L, Havu N. Histopathological classification of nonantral gastric endocrine growths in man. Digestion. 1988;41:185-200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Okada K, Kijima H, Chino O, Matsuyama M, Okamoto Y, Yamamoto S, Tanaka M, Inokuchi S, Makuuchi H. Multiple gastric carcinoids associated with hypergastrinemia. A review of five cases with clinicopathological analysis and surgical strategies. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:4417-4422. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Zhang L, Ozao J, Warner R, Divino C. Review of the pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of type I gastric carcinoid tumor. World J Surg. 2011;35:1879-1886. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |