Published online Dec 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12888

Peer-review started: April 21, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Revised: August 3, 2015

Accepted: September 30, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

Published online: December 7, 2015

Processing time: 231 Days and 0.5 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether posture affects the accuracy of 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) detection in partial gastrectomy patients.

METHODS: We studied 156 consecutive residual stomach patients, including 76 with H. pylori infection (infection group) and 80 without H. pylori infection (control group). H. pylori infection was confirmed if both the rapid urease test and histology were positive during gastroscopy. The two groups were divided into four subgroups according to patients’ posture during the 13C-UBT: subgroup A, sitting position; subgroup B, supine position; subgroup C, right lateral recumbent position; and subgroup D, left lateral recumbent position. Each subject underwent the following modified 13C-UBT: 75 mg of 13C-urea (powder) in 100 mL of citric acid solution was administered, and a mouth wash was performed immediately; breath samples were then collected at baseline and at 5-min intervals up to 30 min while the position was maintained. Seven breath samples were collected for each subject. The cutoff value was 2.0‰.

RESULTS: The mean delta over baseline (DOB) values in the subgroups of the infection group were similar at 5 min (P > 0.05) and significantly higher than those in the corresponding control subgroups at all time points (P < 0.01). In the infection group, the mean DOB values in subgroup A were higher than those in other subgroups within 10 min and peaked at the 10-min point (12.4‰± 2.4‰). The values in subgroups B and C both reached their peaks at 15 min (B, 13.9‰± 1.5‰; C, 12.2‰± 1.7‰) and then decreased gradually until the 30-min point. In subgroup D, the value peaked at 20 min (14.7‰± 1.7‰). Significant differences were found between the values in subgroups D and B at both 25 min (t = 2.093, P = 0.043) and 30 min (t = 2.141, P = 0.039). At 30 min, the value in subgroup D was also significantly different from those in subgroups A and C (D vs C: t = 6.325, P = 0.000; D vs A: t = 5.912, P = 0.000). The mean DOB values of subjects with Billroth I anastomosis were higher than those of subjects with Billroth II anastomosis irrespectively of the detection time and posture (P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Utilization of the left lateral recumbent position during the procedure and when collecting the last breath sample may improve the diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-UBT in partial gastrectomy patients.

Core tip: The efficiency of the 13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in patients after gastrectomy is still controversial. Many factors may affect the diagnostic accuracy, and posture is especially important. We suggest that residual stomach patients should be kept in the horizontal position on the left side during the procedure and when collecting the last breath sample in order to improve the accuracy of detection of H. pylori infection.

- Citation: Yin SM, Zhang F, Shi DM, Xiang P, Xiao L, Huang YQ, Zhang GS, Bao ZJ. Effect of posture on 13C-urea breath test in partial gastrectomy patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(45): 12888-12895

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i45/12888.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i45.12888

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), a spiral gram-negative bacterium, can colonize epithelial cells of the gastric mucosa under micro-aerobic growth condition. H. pylori infection leads to multiple gastric disorders, including chronic active gastritis, ulcer, adenocarcinoma, and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[1-3]. It has also been considered one of the factors inducing residual gastric mucosa carcinogenesis in postoperative patients with early-stage gastric carcinoma[4]. Therefore, it is crucial to accurately detect whether H. pylori is present in patients who underwent partial gastrectomy.

Due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations, H. pylori detection in residual stomach relies on additional examinations. Although the 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT), a noninvasive diagnostic method for H. pylori infection, is inferior to bacterial culture and histological examinations[5], it represents a fast, safe, and reliable technology which is able to accurately determine H. pylori infection in an intact stomach. Accordingly, it has been widely used in the general population[6,7]. However, a standardized international protocol defining specific steps, detection methods, and the cutoff value for the 13C-UBT is currently lacking. In addition, 13C-UBT diagnosis is limited by some factors, such as fasting and mouth washing, dose and dosage form of 13C-urea (tablet, capsule, or powder), presence of test meal, time of breath sample collection and storage, and cutoff values[5,8-10]. Since the bacterial load is lower and emptying of the stomach is faster in residual stomach subjects, there are some disputes on the efficiency of the 13C-UBT in gastrectomy patients[5,11-15]. In particular, the influence of posture on the results of the 13C-UBT in detecting H. pylori infection in partial gastrectomy patients has been a focus of attention. In the existing reports on the 13C-UBT diagnosis and treatment for H. pylori infection in such patients, researchers from different countries utilized the conventional 13C-UBT protocol for the general population[7,16,17]. Gastric remnant subjects were kept in the sitting position when breath samples were collected, and they usually maintained this position between the collections[14,18]. Only a few studies included the horizontal supine position[15] or the horizontal position on the left side[11,12]. Although Togashi et al[9] have performed a preliminary study of different positions (left-lateral horizontal, sitting, or supine position), which position is more suitable for gastrectomy subjects is not yet fully addressed.

The purpose of the present study was to assess whether the position of partial gastrectomy patients during the test affects the diagnostic accuracy of 13C-UBT for H. pylori infection. We attempted to develop a convenient as well as reliable means for H. pylori detection and follow-up after eradication therapy in patients who underwent partial gastrectomy.

The infection group consisted of 76 patients with partial gastrectomy who visited Huadong Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University from November 2012 to March 2015. H. pylori infection was confirmed by histopathological examination. The following inclusion criteria were used: the time interval after the subtotal gastrectomy was at least 1 year; the surgical procedure was distal gastrectomy with Billroth I or II (B-I or B-II) anastomosis; the indication for surgery included benign peptic ulcer or early gastric cancer; endoscopy, histological examination, and rapid urease test (RUT) were performed before and after the operation.

The control group contained 80 patients who underwent partial gastrectomy during the same period, met the inclusion criteria, and were H. pylori-negative based on histological examination. Patient characteristics such as age, sex, disease etiology, reconstruction method, and postoperative course in the control group were matched to those in the infected group.

In both groups, the subjects were divided into four subgroups according to their posture after 13C-urea administration: subgroup A, sitting position; subgroup B, supine position on a bed; subgroup C, horizontal position on the right side; as well as subgroup D, horizontal position on the left side. The patients were assigned randomly to A, B, C, or D subgroup according to their reconstruction method. The following exclusion criteria were used: H. pylori eradication therapy prior to the present study; treatment with antibiotics, proton pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists, or bismuth salts within 1 mo before the study; absence of endoscopic examination, RUT, pre- and post-operative histological detection for H. pylori; presence of test contraindications; distal gastrectomy without B-I or B-II anastomosis; and previous gastrointestinal surgery history. The subjects were excluded if they fulfilled any of the above criteria.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of Huadong Hospital Affiliated to Fudan University. All individuals provided written informed consent. The characteristics of the patients in the infection and control groups are shown in Table 1.

| Infection group | Statistic | P value | Control group | Statistic | P value | |||||||

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |||||

| (n = 19) | (n = 19) | (n 19) | (n = 19) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | (n = 20) | |||||

| Age (yr) | 59.9 ± 11.2 | 63.1 ± 9.2 | 66.1 ± 10.9 | 66.0 ± 12.5 | F = 1.341 | 0.268 | 58.7 ± 12.1 | 62.0 ± 8.5 | 65.2 ± 10.7 | 61.7 ± 14.1 | F = 1.081 | 0.362 |

| Sex (M:F) | 12:7 | 14:5 | 14:5 | 13:6 | χ2 = 0.686 | 0.877 | 15:5 | 14:6 | 15:5 | 13:7 | χ2 = 0.671 | 0.880 |

| Indication for gastrectomy | χ2 = 0.452 | 0.929 | χ2 = 0.251 | 0.969 | ||||||||

| Peptic ulcer | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 | - | - | 5 | 6 | 5 | 6 | - | - |

| Early-stage gastric cancer | 12 | 11 | 13 | 12 | - | - | 15 | 14 | 15 | 14 | - | - |

| Reconstructive procedure | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| B-I | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | - | - | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | - | - |

| B-II | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | - | - | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | - | - |

| Interval (yr) | 8.9 ± 5.9 | 7.4 ± 5.1 | 7.3 ± 3.9 | 7.9 ± 4.9 | F = 0.429 | 0.733 | 8.6 ± 6.0 | 7.6 ± 5.8 | 7.8 ± 5.0 | 8.4 ± 4.6 | F = 0.150 | 0.929 |

Modified 13C-UBT test was conducted in each participant within a week after the endoscopy. Overnight fasting was required before the test. In the following morning, breath samples were taken at baseline (T0) and at 5-min intervals up to 30 min (T5, T10, T15, T20, T25, and T30) after an oral administration of 13C-labelled urea powder (75 mg/100 mL citric acid solution; AltaChem Pharma Ltd., Canada) and an immediate mouth wash to remove the residual compound. The first breath sample was taken in the sitting position. The patients were then placed in the positions according to their subgroups and maintained them for 30 min while the rest of the breath samples were collected. These gas samples were collected separately for analysis of the 13CO2/12CO2 ratio (Δ13CO2, ‰) with an isotope mass spectrometer (IRIS 3, Frankfurt, Germany), which was normalized using a standard gas sample. The analysis was performed by Wagner Analysen Technik GmbH (Bremen, Germany). Differences between the values at T5, T10, T15, T20, T25, and T30 and those at T0 were presented as delta over baseline (DOB, Δδ, ‰). Based on the related reports[5,11,12] and our previous study of 194 samples[19], the cutoff value for this diagnostic test was defined as 2.0‰. Subjects with a DOB > 2.0‰ were considered H. pylori-positive, whereas those with a DOB < 2.0‰ were considered H. pylori-negative.

Four gastric mucosa biopsy samples were collected separately from the greater curvature of the mid-to-high body as well as the gastric side of the anastomotic stoma, in that order (2 samples from each position), during endoscopy for RUT and histological examination. A positive RUT result was defined as a color alteration from yellow to red during a 24-h period. In most patients, this color change occurred within 120 min. For histological examinations such as hematoxylin and eosin (HE) or Giemsa staining, curved rods were used to identify H. pylori in a sectioned specimen. The result of the histological examination was considered positive if H. pylori was detected at any site. Only patients with positive RUT and positive histological test were defined as the ones with H. pylori infection[1]. Conversely, a patient was considered uninfected when both tests were negative. If inconsistent results were obtained between the RUT and histological test, the corresponding patients were excluded. All biopsy specimens were assessed by a single pathologist who was blinded to the results of endoscopic examinations and UBT for H. pylori.

We used the cancer staging system from the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Cancer Staging Manual (version 7th)[20].

Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) software (version 16.0) was used in this study for all statistical analyses. Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD and analyzed by Student’s t test, one-way analysis of variance or Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test. Classified variables were analyzed by χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. P values < 0.05 were defined as statistical significance.

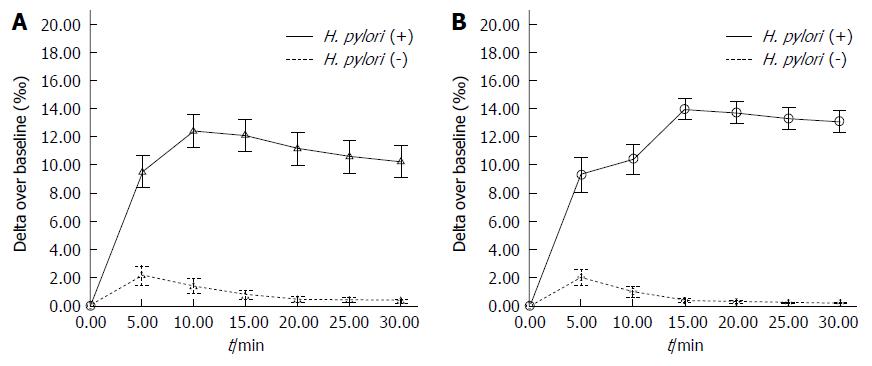

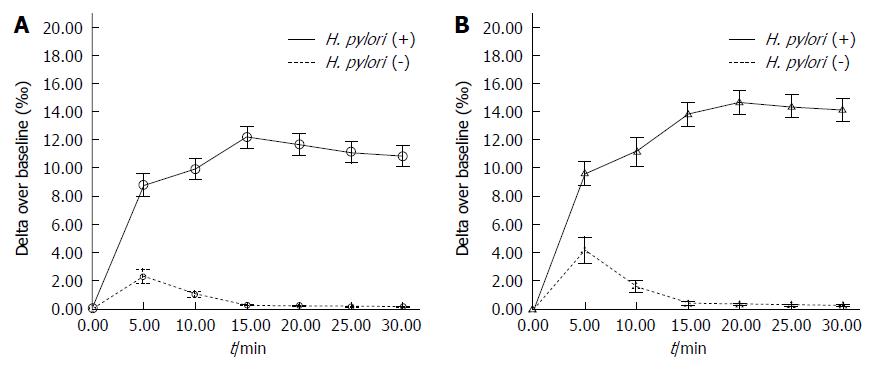

The patients in the infection group (76 subjects) and control group (80 subjects) were divided into four subgroups: A, B, C, and D. As a result, there were 19 infected patients (B-I, 11 subjects; B-II, 8 subjects) and 20 uninfected patients (B-I, 10 subjects; B-II, 10 subjects) in each subgroup. No statistically significant differences were found in age, sex, indications for gastrectomy, or postoperative course between the subgroups within the infection group and the control group (P > 0.05). The subjects in the infection and control groups were placed in the sitting position, supine position, and right or left lateral recumbent position according to their subgroups. Significantly higher DOB values for each subgroup in the infection group were detected compared with the control group at T5 and thereafter regardless of the patients’ posture (P < 0.01). No borderline or false-negative results were found in any position and at any time point in the infection group. In the control group, no borderline or false-positive results were found in any position at T10, T15, T20, T25, or T30. The mean DOB values for the four subgroups of each group are plotted in Figures 1 and 2.

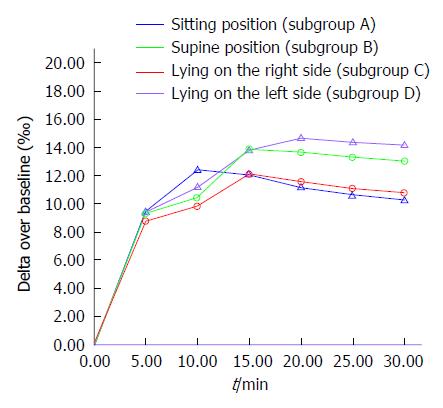

According to the DOB value curves in the infection group (Figure 3), the mean DOB values in the subgroups were similar at T5 (F = 0.421, P = 0.738). The mean values in subgroup A were higher than in other subgroups within the first 10 min. At T10, the mean DOB value was 12.4‰± 2.4‰, exceeding the mean DOB value in subgroup D (11.2‰± 2.1‰, t = 1.617, P = 0.115) and being significantly higher than those in subgroups B (10.4‰± 2.4‰, t = 2.634, P = 0.012) and C (9.9‰± 1.6‰, t = 3.811, P = 0.001). The values in subgroups B and C both reached their peaks (B: 13.9‰± 1.5‰, C: 12.2‰± 1.7‰) at T15 and then both decreased gradually until 30 min. In subgroup D, the value peaked (14.7‰± 1.7‰) at T20 and was significantly higher than those at T5, T10, and T15 (F = 30.628, P = 0.000) but did not differ significantly from those at T25 and T30 (F = 0.396, P = 0.675). At T20, no statistically significant values were determined (t = 1.812, P = 0.078) between the subgroups D and B (13.7‰± 1.60‰), but significant differences were observed between the values in these two subgroups at both T25 (D: 14.4‰± 1.69‰, B: 13.3‰± 1.60‰, t = 2.093, P = 0.043) and T30 (D: 14.2‰± 1.7‰, B: 13.1‰± 1.6‰, t = 2.141, P = 0.039). At T30, the value in subgroup D was also significantly different from those in subgroups A (10.3‰± 2.3‰, t = 5.912, P = 0.000) and C (10.8‰± 1.6‰, t = 6.325, P = 0.000).

In the infection group, the mean DOB values of the subjects with B-I anastomosis were higher than those of the subjects with B-II anastomosis irrespectively of the time point and position. However, these differences (except at T5, T10, and T15 in subgroup D) were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Table 2 shows the reconstructive procedure and mean DOB values for the subjects in the infection group.

| Subgroup | Time | DOB ( B-I) | DOB ( B-II) | t value | P value |

| A | T5 | 9.67 ± 1.79 | 9.30 ± 3.00 | 0.314 | 0.760 |

| T10 | 12.57 ± 1.92 | 12.18 ± 3.06 | 0.324 | 0.752 | |

| T15 | 12.28 ± 1.95 | 11.89 ± 3.08 | 0.319 | 0.756 | |

| T20 | 11.50 ± 1.93 | 10.80 ± 2.94 | 0.588 | 0.568 | |

| T25 | 10.91 ± 1.90 | 10.20 ± 2.98 | 0.592 | 0.566 | |

| T30 | 10.58 ± 1.88 | 9.86 ± 2.93 | 0.609 | 0.555 | |

| B | T5 | 9.74 ± 2.33 | 8.74 ± 2.85 | 0.841 | 0.412 |

| T10 | 10.69 ± 2.11 | 10.01 ± 2.60 | 0.628 | 0.538 | |

| T15 | 14.20 ± 1.56 | 13.56 ± 1.56 | 0.880 | 0.391 | |

| T20 | 13.99 ± 1.59 | 13.35 ± 1.62 | 0.861 | 0.401 | |

| T25 | 13.57 ± 1.60 | 12.91 ± 1.62 | 0.885 | 0.389 | |

| T30 | 13.34 ± 1.56 | 12.69 ± 1.59 | 0.890 | 0.386 | |

| C | T5 | 8.96 ± 1.69 | 8.69 ± 1.71 | 0.344 | 0.735 |

| T10 | 10.03 ± 1.53 | 9.81 ± 1.67 | 0.288 | 0.777 | |

| T15 | 12.33 ± 1.74 | 12.05 ± 1.73 | 0.347 | 0.733 | |

| T20 | 11.79 ± 1.69 | 11.50 ± 1.72 | 0.364 | 0.720 | |

| T25 | 11.26 ± 1.62 | 10.99 ± 1.69 | 0.352 | 0.729 | |

| T30 | 10.95 ± 1.62 | 10.72 ± 1.62 | 0.295 | 0.771 | |

| D | T5 | 10.21 ± 1.54 | 8.39 ± 2.18 | 2.136 | 0.048 |

| T10 | 12.12 ± 1.57 | 9.98 ± 2.56 | 2.446 | 0.026 | |

| T15 | 14.51 ± 1.39 | 12.91 ± 1.76 | 2.213 | 0.041 | |

| T20 | 15.32 ± 1.37 | 13.83 ± 1.82 | 2.049 | 0.056 | |

| T25 | 15.04 ± 1.38 | 13.56 ± 1.77 | 2.057 | 0.055 | |

| T30 | 14.84 ± 1.37 | 13.33 ± 1.82 | 2.068 | 0.054 |

The 13C-UBT is an internationally recognized gold standard for H. pylori infection detection and anti-H. pylori drug efficacy monitoring[2]. It has been widely recommended, even for children, gravidas, and the elderly[7]. However, the application of 13C-UBT in diagnosing H. pylori infection in partial gastrectomy patients remains controversial. In spite of the fact that the gastric remnant is not suitable for colonization by H. pylori and its survival, the bacteria can still be transmitted via fecal-oral, gastric-oral, oral-oral, and other ways. Gisbert et al[5] concluded that the 13C-UBT was not suitable for gastric remnant patients who underwent Billroth gastrectomy as the ingested 13C-urea passed through the stomach faster and entered the duodenum (B-I) and small intestine (B-II) more easily, which would definitely impact the diagnostic accuracy. However, other reports[9,11,12] showed that, with a proper procedure and an appropriate cutoff value, the 13C-UBT was a reliable detection method in patients after gastrectomy.

Miwa et al[21] investigated the effect of different positions (supine position and sitting position) and of changing the position by rolling during the period after 13C-urea injection on the diagnostic performance of the 13C-UBT for H. pylori infection in infected patients with intact stomach. The study revealed that posture affected the DOB values at T5 and T10 but did not affect the results at the 15-min, 20-min, and later time points. Compared with the intact stomach, the anatomy, pH, motility, and distribution of H. pylori in the residual stomach are considerably altered, which makes the posture during the 13C-UBT an important clinical factor. Therefore, we conducted this study to determine the optimal posture for residual stomach subjects.

Our study showed that the DOB values in the control group were lower compared with the infection group at all time points, and the first positive results appeared at T5, which might be due to the presence of urease-positive organisms in the oral cavity early in the procedure. The study by Lee et al[8] proved that the effect of oral bacteria was most remarkable at T5 and T10, decreased at T15, and was weakest at T30. However, Togashi et al[9] found that oral organisms could affect the final results in residual stomach subjects. Therefore, we suggest that a thorough cleaning of the oral cavity with a mouth wash is important in residual stomach patients after 13C-urea administration, especially if the powder form is used.

Based on comparing the different subgroups of the infection group, we found that the posture in the period after the first measurement affected the results to some degree. The DOB values peaked at a different point in each subgroup, with those in the sitting position subgroup reaching the maximum at the earliest point (T10) and those in the left lateral recumbent position peaking at the latest point (T20). Although the DOB values in all subgroups were similar at T5, they differed substantially thereafter. Thus, the DOB values in the subgroups diverged at T10, suggesting that they may be affected by the posture early in the test, except for the component caused by the presence of residual organisms in the oral cavity. Furthermore, during the late stage (especially at T20 and thereafter), the DOB values were mainly affected by the posture. As the gastric antrum, the most common site of colonization by H. pylori, is removed during the operation, the H. pylori infection rate in patients after B-I or B-II gastrectomy is reduced by about 50%[22]. Park et al[23] reported H. pylori infection rates of 70.8% (B-I) and 45.9% (B-II). From the viewpoint of pathophysiology, gastric emptying is faster in the absence of the gastric antrum, and the clearance of 13C-urea is further accelerated in the sitting position by the gravity force. Together, these factors reduce the time of exposure of the gastric mucosa to 13C-urea, leading to a significant decrease in DOB values during the late stage of the test. This is the main reason of the low diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-UBT in residual stomach patients. A test meal, such as citric acid solution, commonly used in the routine 13C-UBT to prolong gastric emptying and improve the diagnostic accuracy for H. pylori infection is ineffective in partial gastrectomy subjects[15]. The time dependence of the DOB values in the right lateral recumbent position group, which was also affected by gastric anatomy and motility, was similar to that in the sitting position group. In the left lateral recumbent position, 13C-urea clearance was delayed, which allowed better access of the substrate to H. pylori urease, resulting in the DOB values peaking at a later time point (T20) and remaining relatively stable during the late stage of the test. The DOB values in subgroup D at T25 and T30 were higher than those in the remaining three subgroups. For clinical convenience[16,24] and to avoid the influence of intestinal bacteria during the late stage, we did not collect breath samples beyond 30 min. Urita et al[24] suggested that the routine 13C-UBT should be conducted for at least 20 min to diagnose H. pylori infection. Combined with our findings, the duration of 30 or 25 min with the subject positioned horizontally on the left side during the procedure might be optimal for residual stomach patients.

Based on the effect of posture on DOB values, we conclude that the patients’ posture during breath samples collection could also influence final results. To balance the accuracy and convenience, we recommend that residual stomach patients are placed in the sitting position when collecting the first sample and in the left lateral recumbent position thereafter, including when collecting the last sample.

We found no significant differences in DOB values between the groups with different reconstruction methods (B-I and B-II), indicating that the anastomosis type does not affect the diagnostic value of 13C-UBT, which is consistent with the study of Togashi et al[9]. The differences in DOB values between the subjects with B-I and B-II anastomoses at T5, T10, and T15 in infection subgroup D suggest that the late stage of the test (T20 and thereafter) may be optimal for avoiding the effect of the operation type. Moreover, the left lateral recumbent position during the 13C-UBT procedure was most suitable for the B-I and B-II subjects. In this study, we selected subjects with B-I and B-II gastrectomy to simplify the analysis and to be able to use universal conditions during the test, and other operative methods will require further research.

As the H. pylori load is lower and gastric emptying is faster after the operation, the CO2 concentration in breath samples may be insufficient to detect positive results, and the cutoff value for the 13C-UBT in residual stomach subjects should be lower than that in the general population[1,5,12]. Therefore, the cutoff value in this study was reduced from 3.5‰ to 2‰. According to the literature[9], the sensitivity of the 13C-UBT for gastric mucosa H. pylori detection is 82.2%-96.3%, and the specificity is 94.6%-100%. Based on the comparison with the results of histological examinations, Kubota et al[11] found that the most appropriate cutoff value in residual stomach subjects was 2.0‰ as determined using a receiver operating characteristic curve. Under these conditions, high sensitivity (96.3%), specificity (100%), and accuracy (97.1%) were achieved. Our previous study[19] found that, when the cutoff value was 2.0‰, the 13C-UBT had a high sensitivity (88.6%) and specificity (94.9%), and its accuracy (92.6%) was similar to that of the invasive test method (histological examination, 93.5%), with good consistency between the two approaches (Kappa = 0.84). Accordingly, the 2.0‰ cutoff value is more suitable for residual stomach subjects than the conventional value of 3.5‰.

Gisbert et al[25] suggested that values in the 2.0‰-5.0‰ range represented borderline results. We did not observe such borderline results in the present study. We suggest that a reexamination by the 13C-UBT or other tests should be performed to verify the results for residual stomach patients whose DOB values are within the above-mentioned range, and special attention should be paid in cases with DOB values around 5‰.

In conclusion, unlike in the general population, posture can influence the diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-UBT in residual stomach subjects, especially during the late stage of the test (20 min and thereafter). We suggest that the mouth should be washed after 13C-urea solution administration and that a cutoff value of 2.0‰ and the horizontal position on the left side should be used during the procedure (whose optimal time is 30 or 25 min) and when collecting the last breath sample. The modified 13C-UBT may be a simple, safe, and effective method for diagnosing H. pylori infection and for long-term follow-up after eradication therapy in residual stomach subjects.

Accurate detection of the presence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) in patients with partial gastrectomy is of crucial importance. The efficiency of the 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT) in the diagnosis of H. pylori infection in patients after gastrectomy is still controversial.

Many factors may affect the diagnostic accuracy, and posture is especially important.

Unlike in the general population, posture may affect the diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-UBT in residual stomach subjects, especially during the late stage of the test (20 min and thereafter). Utilization of the left lateral recumbent position during the procedure and when collecting the last breath sample may improve the diagnostic accuracy of the 13C-UBT in partial gastrectomy patients.

The modified 13C-UBT may be a simple, safe, and effective method for diagnosing H. pylori infection and for long-term follow-up after eradication therapy in residual stomach subjects.

This manuscript is interesting to me. Authors meticulously designed four subgroups in H. pylori infection and control patients with different postures for demonstrating the significance of outcome of 13C-urea breath test. The data analysis is confident and exact. I think authors need amend some information of outcome of 13C-urea breath test in the same patient with four different postures, which can provide the more trustful results.

P- Reviewer: Bener A S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain C, Bazzoli F, El-Omar E, Graham D, Hunt R, Rokkas T, Vakil N, Kuipers EJ. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection: the Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut. 2007;56:772-781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1396] [Cited by in RCA: 1350] [Article Influence: 75.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 819] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Tian XY, Zhu H, Zhao J, She Q, Zhang GX. Diagnostic performance of urea breath test, rapid urea test, and histology for Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with partial gastrectomy: a meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:285-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sinning C, Schaefer N, Standop J, Hirner A, Wolff M. Gastric stump carcinoma - epidemiology and current concepts in pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2007;33:133-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Gisbert JP, Pajares JM. 13C-urea breath test in the management of Helicobacterpylori infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Braden B, Lembcke B, Kuker W, Caspary WF. 13C-breath tests: current state of the art and future directions. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:795-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Campuzano-Maya G. An optimized 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of H pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:5454-5464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lee TH, Yang JC, Lee SC, Farn SS, Wang TH. Effect of mouth washing on the. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:261-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Togashi A, Matsukura N, Kato S, Masuda G, Ohkawa K, Tokunaga A, Yamada N, Tajiri T. Simple and accurate (13)C-urea breath test for detection of Helicobacter pylori in the remnant stomach after surgery. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Colaiocco Ferrante L, Papponetti M, Marcuccitti J, Neri M, Festi D. 13C-urea breath test for helicobacter pylori infection: stability of samples over time. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1999;34:942-943. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Kubota K, Shimoyama S, Shimizu N, Noguchi C, Mafune K, Kaminishi M, Tange T. Studies of 13C-urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients after partial gastrectomy. Digestion. 2002;65:82-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kubota K, Hiki N, Shimizu N, Shimoyama S, Noguchi C, Tange T, Mafune K, Kaminishi M. Utility of [13C] urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori detection in partial gastrectomy patients. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:2135-2138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adamopoulos AB, Stergiou GS, Sakizlis GN, Tiniakos DG, Nasothimiou EG, Sioutis DK, Achimastos AD. Diagnostic value of rapid urease test and urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori detection in patients with Billroth II gastrectomy: a prospective controlled trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:4-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schilling D, Jakobs R, Peitz U, Sulliga M, Stolte M, Riemann J, Labenz J. Diagnostic accuracy of (13)C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with partial gastric resection due to peptic ulcer disease: a prospective multicenter study. Digestion. 2001;63:8-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sheu BS, Lee SC, Lin PW, Wang ST, Chang YC, Yang HB, Chuang CH, Lin XZ. Carbon urea breath test is not as accurate as endoscopy to detect Helicobacter pylori after gastrectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:670-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ohara S, Kato M, Asaka M, Toyota T. Studies of 13C-urea breath test for diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:6-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Logan RP, Polson RJ, Misiewicz JJ, Rao G, Karim NQ, Newell D, Johnson P, Wadsworth J, Walker MM, Baron JH. Simplified single sample 13Carbon urea breath test for Helicobacter pylori: comparison with histology, culture, and ELISA serology. Gut. 1991;32:1461-1464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kwon YH, Kim N, Lee JY, Choi YJ, Yoon K, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH. The diagnostic validity of the (13)c-urea breath test in the gastrectomized patients: single tertiary center retrospective cohort study. J Cancer Prev. 2014;19:309-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Yin SM, Zhang GS, Xiang P, Xiao L, Huang YQ, Chen J, Bao ZJ, Yu XF. Application value of 13C-urea breath test in the diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastric remnant. Zhongguo Xiaohua Zazhi. 2012;32:669-673. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1471-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5537] [Cited by in RCA: 6460] [Article Influence: 430.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Miwa H, Murai T, Ohkura R, Kawabe M, Tanaka H, Ogihara T, Watanabe S, Sato N. Effect of fasting subjects’ posture on 13C-urea breath test for detection of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 1997;2:82-85. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Danesh J, Appleby P, Peto R. How often does surgery for peptic ulceration eradicate Helicobacter pylori? Systematic review of 36 studies. BMJ. 1998;316:746-747. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Park S, Chun HJ. Helicobacter pylori infection following partial gastrectomy for gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2765-2770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Urita Y, Hike K, Torii N, Kikuchi Y, Kanda E, Kurakata H, Sasajima M, Miki K. Breath sample collection through the nostril reduces false-positive results of 13C-urea breath test for the diagnosis of helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:661-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gisbert JP, Olivares D, Jimenez I, Pajares JM. Long-term follow-up of 13C-urea breath test results after Helicobacter pylori eradication: frequency and significance of borderline delta13CO2 values. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |