Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12729

Peer-review started: May 22, 2015

First decision: June 2, 2015

Revised: June 23, 2015

Accepted: August 30, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 190 Days and 20.7 Hours

Hepatic artery thrombosis is a serious complication after liver transplantation which often results in biliary complications, early graft loss, and patient death. It is generally thought that early hepatic artery thrombosis without urgent re-vascularization or re-transplantation almost always leads to mortality, especially if the hepatic artery thrombosis occurs within a few days after transplantation. This series presents 3 cases of early hepatic artery thrombosis after living donor liver transplantation, in which surgical or endovascular attempts at arterial re-vascularization failed. Unexpectedly, these 3 patients survived with acceptable graft function after 32 mo, 11 mo, and 4 mo follow-up, respectively. The literatures on factors affecting this devastating complication were reviewed from an anatomical perspective. The collective evidence from survivors indicated that modified nonsurgical management after liver transplantation with failed revascularization may be sufficient to prevent mortality from early hepatic artery occlusion. Re-transplantation may be reserved for selected patients with unrecovered graft function.

Core tip: We present 3 cases of early hepatic artery thrombosis after living donor liver transplantation, in which surgical or endovascular attempts at arterial re-vascularization failed. Unexpectedly, these 3 patients survived with acceptable graft function after 32 mo, 11 mo, and 4 mo follow-up, respectively. The literatures on factors affecting this devastating complication were reviewed from an anatomical perspective. Our three cases raise the possibility that a modified nonsurgical management strategy may be sufficient for recovery from early hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation with failed revascularization procedures.

- Citation: Hsiao CY, Ho CM, Wu YM, Ho MC, Hu RH, Lee PH. Management of early hepatic artery occlusion after liver transplantation with failed rescue. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(44): 12729-12734

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i44/12729.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12729

Hepatic artery thrombosis (HAT) is a serious complication after liver transplantation (LT) which often results in biliary complications, early graft loss, and patient death[1-3]. HAT is defined according to the time of onset, with early HAT occurring 30 d or less after LT and late HAT occurring more than 30 d after LT[2]. In a large study of 21822 patients who underwent LT[3], the overall incidence of early HAT was 4.4%, higher in children than in adults (8.3% vs 2.9%), and diagnosed at a median of postoperative day (POD) 7. Early HAT resulted in an overall re-transplantation rate of 53.1% (children higher than adults, 62% vs 50%) and an overall mortality rate of 33.3% (adults higher than children, 34.3% vs 25%)[3]. It is generally thought that early HAT (especially within the first few days after transplantation) without urgent re-vascularization or re-transplantation almost always leads to mortality. However, in this case series, 3 patients with early HAT after living donor LT with failed arterial re-vascularization survived with acceptable graft function after 32 mo, 11 mo, and 4 mo follow-up, respectively (Table 1). Possible explanations were discussed from an anatomical perspective. Our three cases raise the possibility that a modified nonsurgical management strategy may be sufficient for recovery from early HAT after LT with failed revascularization procedures.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |

| Age (yr) | 60 | 49 | 13 |

| Gender | Female | Male | Male |

| Indication of LT | HCV/HCC | Alcoholic cirrhosis | PSC |

| Donor age (yr)/gender | 31/male | 23/male | 44/female |

| Graft | Right lobe | Right lobe | Left lobe |

| HA anastomosis condition | 9-0, once 82 min | 9-0, twice 36 + 43 min | 8-0, twice 30 + 99 min |

| Time of diagnosis of HAT | POD 7 | POD 1 | POD 2 |

| Management | Surgical reanastomosis, failed | Angiographic procedure, failed | Angiographic procedure, failed |

| Discharge time | POD 31 | POD 17 | POD 36 |

| Follow-ups | 32 mo | 11 mo | 4 mo |

| (BTI x 3) | (BTI x 1) | (no BTI) |

A 60-year-old woman with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatitis C virus-related liver cirrhosis underwent living donor LT (right lobe from her 31-year-old son). Hepatic artery anastomosis was performed smoothly under an operating microscope. Extubation was performed on POD 2. However, she had abrupt elevation of liver enzymes and hyperbilirubinemia on POD 7 [alanine transaminase (ALT) 1183 U/L from 211 U/L on POD 6, total bilirubin (T-bil) 4.25 mg/dL from 1.78 mg/dL]. Doppler ultrasonography showed no HA blood flow. CT angiography further disclosed the absence of intra-hepatic arterial flow and a hypodense lesion suspected to be an infarction at S7-8 of the liver. Angiography confirmed the diagnosis of thrombosis at the proper HA anastomosis (Figure 1), and the angiographic micro-catheter failed to pass through the occlusion site. She then underwent urgent laparotomy. Re-anastomosis of the HA failed and the HA graft was not suitable for another attempt at re-anastomosis. Under supportive treatment, the patient’s liver function recovered gradually (POD 31: ALT 160 U/L, T-bil 2.02 mg/dL) and she was discharged 31 d after liver transplantation. The patient took aspirin 100 mg daily thereafter. She had 3 episodes of biliary tract infection (BTI) on the 2nd, 4th, and 5th month after LT, which required hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics treatment. CT scan at the post-operative 5th month showed no remarkable intrahepatic duct dilatation or infarction of the liver parenchyma. She has remained well with normal graft function after 32 mo of follow-up.

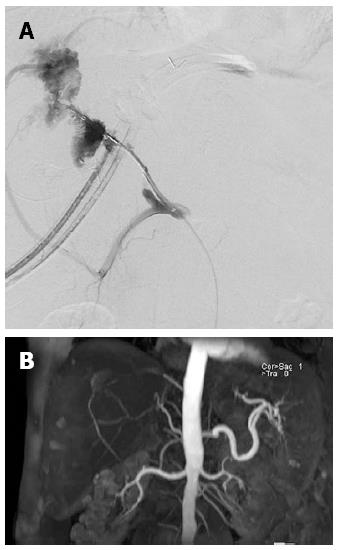

A 49-year-old man with alcoholic liver cirrhosis underwent living donor LT (right lobe from her 23-year-old son). The HA was anastomosed end-to-end under an operating microscope. Extubation was performed on POD 1. Elevation of liver enzymes and hyperbilirubinemia were found on POD 1 (ALT 456 U/L from 17 U/L, T-bil 7.78 mg/dL from 1.73 mg/dL). Doppler ultrasonography showed no HA flow. CT angiography disclosed total occlusion of the grafted HA. An attempt to place an intra-arterial catheter for endovascular management on POD 1 resulted in extravasation distal to the anastomosis site. On POD3, an intra-arterial catheter was placed at the anastomosis site for endovascular thrombolysis, but still no arterial flow was noted. On POD7, the intra-arterial catheter was re-implanted for urokinase infusion (60000 IU/h for 4 h), but angiography on POD8 showed persistent thrombosis at the anastomosis site (Figure 2A). The patient’s liver function improved gradually under supportive treatment (POD 17: AST 53 U/L, ALT 169 U/L, T-bil 2.98 mg/dL, D-bil 1.51 mg/dL) and he was discharged on POD 17 after LT. The patient took aspirin 100 mg daily after discharge. In the following 9 mo, he had one episode of BTI at the 7th month after LT which required hospitalization for intravenous antibiotics treatment. Magnetic resonance angiography on the 8th month after LT showed recanalization of the intrahepatic artery via another artery (possibly the right inferior phrenic artery; Figure 2B). He has remained well with normal graft function after 11 mo of follow-up.

A 13-year-old boy with primary sclerosing cholangitis (after common bile duct excision and Reux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy at age 11) underwent living donor LT (left lobe from his 44-year-old mother). Hepatic artery anastomosis had been performed twice because of donor artery intima dissection. He had elevated liver enzymes on POD1 (ALT 699 U/L from 61 U/L, T-bil 8.21 mg/dL from 1.77 mg/dL). CT on POD 2 showed occlusion of the proper HA at the anastomosis site. Angiography showed total occlusion of the proper HA (Figure 3), prompting urokinase 20000 IU injection through a microcatheter with its tip inserted within the thrombosed proper HA, but in vain. The patient’s liver function improved gradually with no further treatment of the thrombosed HA (POD 36: ALT 23 U/L, T-bil 0.69 mg/dL). He was discharged on POD 36 after LT and prolonged ascites drainage. He has remained well with normal graft function 4 mo after LT without any BTI episode during follow-up.

HAT is a serious complication after LT which often results in patient death and is the 2nd leading cause of early graft failure after primary nonfunction[1]. The etiology of early HAT is thought to be related not only to surgical factors such as vessel kinking, stenotic anastomosis, and intimal dissection, but also to non-surgical factors such as elderly donors, hypercoagulable state, and rejection episodes[4]. Risk factors of early HAT reported in literature include cytomegalovirus mismatch, re-transplantation, use of an arterial conduit, prolonged operation time, low recipient body weight, variant arterial anatomy, lower volume LT hospital[3], and delay in arterial reperfusion[4]. Besides, use of continuous rather than interrupted sutures to anastomose the ends of an hepatic artery was associated with higher incidence of HAT[5]. The most frequent clinical presentation (30%) of early HAT is acute fulminant hepatic failure[1], and the diagnosis of early HAT is often confirmed by thrombo/embolic occlusion of the hepatic artery on Doppler ultrasonography and/or CT/angiography. Routine Doppler ultrasonography in the first 3 d after LT allows early detection of HAT, and makes rescue interventions before liver damage possible[6]. Introduction of microvascular reconstruction has significantly decreased the incidence of HAT[7].

Therapeutic options for HAT include arterial revascularization and re-transplantation. Revascularization could be surgical re-anastomosis (or thrombectomy) or endovascular treatments such as intra-arterial thrombolysis and percutaneous transluminal angioplasty with/without stent placement or balloon dilatation. Although re-transplantation is traditionally the gold standard of therapy for HAT, in areas with organ shortage such as Asia, timely re-transplantation may not be feasible. Thus endovascular or surgical revascularization is often the first line treatment for patients with HAT. Arterial revascularization via endovascular or surgical procedures may reduce graft loss and improve outcome in both adult[8] and pediatric[9] LT recipients with early HAT. Most studies suggest the use of endovascular urokinase or heparin for HAT after LT[10], which has a 68% success rate (with internal bleeding as its most common complication)[10]. Several studies reported that antiplatelet prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of HAT in selected adult patients after LT, with no increase in the incidence of bleeding events and wound complications[11,12].

HAT causes ischemic injury of the biliary system and liver parenchyma leading to biliary necrosis and the formation of liver abscesses[1,2]. In our 3 cases, endovascular or surgical revascularization was performed but failed to restore blood flow. However, the grafts functioned well, without the need for re-transplantation. Recently, Boleslawski et al[13] recommended HA ligation as a reasonable option for HA ruptures following LT. Of the seven patients who received HA ligation for HA rupture, six survived well with functional grafts during follow-up. It is unclear why these patients did not develop severe ischemic cholangiopathy. Looking at this problem from an anatomical perspective, the biliary system has three zones with different blood supplies: the intrahepatic bile ducts, hilar ducts, and extrahepatic bile ducts. The intrahepatic biliary ducts are surrounded by a rich microvascular network (the peribiliary plexus)[14]. Some experimental studies have supported the suggestion of arterioportal communication through the peribiliary plexus[15]. The peribiliary plexus represents a collateral source of arterial blood to the liver when the hepatic artery is occluded[16]. Therefore, biliary ischemia of the distal bile ducts usually occurs because of injury to the arteries supplying the distal extrahepatic ducts but is not always inevitable because of the existence of arterioportal collaterals[17]. If the hepatic ducts of a liver graft were transected at a proximal level during the operation to remove the living donor’s liver, the risk of devastating biliary ischemia after HA occlusion would be expected to be lower because proximal hepatic ducts behave more like the intrahepatic ducts. In 2 of our 3 cases, the bile ducts of the liver grafts were proximally transected, supporting our hypothesis. In case 1, the bile ducts in the right lobe liver graft had two orifices, and in case 3, left donor hepatectomy was performed. Moreover, in a rat model of liver transplantation, arterial reconstruction was regarded as unnecessary and thus not routinely performed[18]. Recent studies reported the same survival rate in LT rats with HA reconstruction and LT rats without HA reconstruction (though the latter are associated with more graft parenchymal damage in the early postoperative period)[15]. The detail mechanism of hepatic arterial collateral formation via inferior phrenic artery is not clear, however, arterial collaterals through the bare area of liver in recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma after transarterial chemoembolization is not uncommon.

Development of HAT within 7 d of LT is an indication of emergency transplant status (UNOS status 1)[19]. However, emergency LT and especially emergency re-transplantation are often associated with lower patient and graft survival as compared with non-emergency LT and elective re-transplantation[20-23]. Considering that the real outcome of early HAT may not be as bad as once thought, patients may not need to undergo high risk emergency re-transplantation routinely. As a result, we recommend a short-term “wait and see” policy when patients developed early HAT even if it happens within 7 d of LT, as long as their biochemical and hemodynamic status remains relatively stable. Re-transplantation may be reserved for select patients who present with unrecovered graft function after early HAT and fail to be rescued by endovascular or surgical intervention. Besides, mesenteric arteriovenous shunt (partial portal arterialization) had been reported effective in preventing hepatic failure caused by interruption of hepatic artery flow, and might also be an option to gain time until collateral arterial vessels develop or re-transplant[24]. In summary, our cases illustrate that very early HAT without successful urgent re-vascularization or urgent re-transplantation may not always lead to mortality. In patients with very early HAT, urgent endovascular intervention or surgical exploration for re-vascularization is recommended. However, when re-vascularization fails, observation with supportive care such as maintaining relatively high blood pressure and arterial patency by anti-platelet therapy may be a feasible strategy. Re-transplantation may be preserved for selected cases such as those who fail to recover graft function.

Three patients presented with symptoms of liver dysfunction within one week after living-donor liver transplantations.

Hepatic artery thrombosis after living donor liver transplantations.

Primary graft nonfunction, rejection, portal vein thrombosis.

The three patients had various degree of elevation of liver enzymes and hyperbilirubinemia.

For three cases, computed tomographic angiography scan showed occlusion of hepatic artery.

No pathological diagnosis in these three cases.

The first patient underwent urgent surgical re-anastomosis of the hepatic artery but failed. All of the three patients underwent endovascular treatment but failed.

One recent study recommended hepatic artery ligation as a reasonable option for hepatic artery ruptures following liver transplantations.

Hepatic artery thrombosis is a serious complication after liver transplantation which often results in biliary complications, early graft loss, and patient death.

These three cases raise the possibility that a modified nonsurgical management strategy may be sufficient for recovery from early hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation with failed revascularization procedures.

The authors have described three cases of early hepatic artery thrombosis after living donor liver transplantation, in which surgical or endovascular attempts at arterial re-vascularization failed. Unexpectedly, these 3 patients survived with acceptable graft function after 32 mo, 11 mo, and 4 mo follow-up, respectively. These cases outlines that a modified nonsurgical management strategy may be sufficient for recovery from early hepatic artery thrombosis.

P- Reviewer: Hashimoto N S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Pareja E, Cortes M, Navarro R, Sanjuan F, López R, Mir J. Vascular complications after orthotopic liver transplantation: hepatic artery thrombosis. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2970-2972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wu L, Zhang J, Guo Z, Tai Q, He X, Ju W, Wang D, Zhu X, Ma Y, Wang G. Hepatic artery thrombosis after orthotopic liver transplant: a review of the same institute 5 years later. Exp Clin Transplant. 2011;9:191-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bekker J, Ploem S, de Jong KP. Early hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation: a systematic review of the incidence, outcome and risk factors. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:746-757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 380] [Cited by in RCA: 376] [Article Influence: 23.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Warner P, Fusai G, Glantzounis GK, Sabin CA, Rolando N, Patch D, Sharma D, Davidson BR, Rolles K, Burroughs AK. Risk factors associated with early hepatic artery thrombosis after orthotopic liver transplantation - univariable and multivariable analysis. Transpl Int. 2011;24:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Coelho GR, Leitao AS, Cavalcante FP, Brasil IR, Cesar-Borges G, Costa PE, Barros MA, Lopes PM, Nascimento EH, da Costa JI. Continuous versus interrupted suture for hepatic artery anastomosis in liver transplantation: differences in the incidence of hepatic artery thrombosis. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3545-3547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | García-Criado A, Gilabert R, Nicolau C, Real I, Arguis P, Bianchi L, Vilana R, Salmerón JM, García-Valdecasas JC, Brú C. Early detection of hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation by Doppler ultrasonography: prognostic implications. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:51-58. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Uchiyama H, Hashimoto K, Hiroshige S, Harada N, Soejima Y, Nishizaki T, Shimada M, Suehiro T. Hepatic artery reconstruction in living-donor liver transplantation: a review of its techniques and complications. Surgery. 2002;131:S200-S204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scarinci A, Sainz-Barriga M, Berrevoet F, van den Bossche B, Colle I, Geerts A, Rogiers X, van Vlierberghe H, de Hemptinne B, Troisi R. Early arterial revascularization after hepatic artery thrombosis may avoid graft loss and improve outcomes in adult liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:4403-4408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Warnaar N, Polak WG, de Jong KP, de Boer MT, Verkade HJ, Sieders E, Peeters PM, Porte RJ. Long-term results of urgent revascularization for hepatic artery thrombosis after pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2010;16:847-855. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Singhal A, Stokes K, Sebastian A, Wright HI, Kohli V. Endovascular treatment of hepatic artery thrombosis following liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2010;23:245-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vivarelli M, La Barba G, Cucchetti A, Lauro A, Del Gaudio M, Ravaioli M, Grazi GL, Pinna AD. Can antiplatelet prophylaxis reduce the incidence of hepatic artery thrombosis after liver transplantation? Liver Transpl. 2007;13:651-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shay R, Taber D, Pilch N, Meadows H, Tischer S, McGillicuddy J, Bratton C, Baliga P, Chavin K. Early aspirin therapy may reduce hepatic artery thrombosis in liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45:330-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Boleslawski E, Bouras AF, Truant S, Liddo G, Herrero A, Badic B, Audet M, Altieri M, Laurent A, Declerck N. Hepatic artery ligation for arterial rupture following liver transplantation: a reasonable option. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1055-1062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Terada T, Ishida F, Nakanuma Y. Vascular plexus around intrahepatic bile ducts in normal livers and portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 1989;8:139-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Cho KJ, Lunderquist A. The peribiliary vascular plexus: the microvascular architecture of the bile duct in the rabbit and in clinical cases. Radiology. 1983;147:357-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Stapleton GN, Hickman R, Terblanche J. Blood supply of the right and left hepatic ducts. Br J Surg. 1998;85:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Deltenre P, Valla DC. Ischemic cholangiopathy. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:235-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kamada N, Sumimoto R, Kaneda K. The value of hepatic artery reconstruction as a technique in rat liver transplantation. Surgery. 1992;111:195-200. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hori T, Gardner LB, Chen F, Baine AM, Hata T, Uemoto S, Nguyen JH. Impact of hepatic arterial reconstruction on orthotopic liver transplantation in the rat. J Invest Surg. 2012;25:242-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wiesner RH. MELD/PELD and the allocation of deceased donor livers for status 1 recipients with acute fulminant hepatic failure, primary nonfunction, hepatic artery thrombosis, and acute Wilson’s disease. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S17-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Bellido CB, Martínez JM, Gómez LM, Artacho GS, Diez-Canedo JS, Pulido LB, Acevedo JM, Bravo MA. Indications for and survival after liver retransplantation. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:637-640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Herden U, Ganschow R, Grabhorn E, Briem-Richter A, Nashan B, Fischer L. Outcome of liver re-transplantation in children--impact and special analysis of early re-transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2014;18:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Montenovo MI, Hansen RN, Dick AA. Outcomes of adult liver re-transplant patients in the model for end-stage liver disease era: is it time to reconsider its indications? Clin Transplant. 2014;28:1099-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hayashi H, Takamura H, Tani T, Makino I, Nakagawara H, Tajima H, Kitagawa H, Onishi I, Shimizu K, Ohta T. Partial portal arterialization for hepatic arterial thrombosis after living-donor liver transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 2012;10:247-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |