Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12653

Peer-review started: January 13, 2015

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: August 26, 2015

Accepted: September 13, 2015

Article in press: September 14, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 328 Days and 16.2 Hours

AIM: To review and evaluate the diagnostic dilemma of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) clinically.

METHODS: From July 2008 to June 2014, a total of 142 cases of pathologically diagnosed XGC were reviewed at our hospital, among which 42 were misdiagnosed as gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) based on preoperative radiographs and/or intra-operative findings. The clinical characteristics, preoperative imaging, intra-operative findings, frozen section (FS) analysis and surgical procedure data of these patients were collected and analyzed.

RESULTS: The most common clinical syndrome in these 42 patients was chronic cholecystitis, followed by acute cholecystitis. Seven (17%) cases presented with mild jaundice without choledocholithiasis. Thirty-five (83%) cases presented with heterogeneous enhancement within thickened gallbladder walls on imaging, and 29 (69%) cases presented with abnormal enhancement in hepatic parenchyma neighboring the gallbladder, which indicated hepatic infiltration. Intra-operatively, adhesions to adjacent organs were observed in 40 (95.2%) cases, including the duodenum, colon and stomach. Thirty cases underwent FS analysis and the remainder did not. The accuracy rate of FS was 93%, and that of surgeon’s macroscopic diagnosis was 50%. Six cases were misidentified as GBC by surgeon’s macroscopic examination and underwent aggressive surgical treatment. No statistical difference was encountered in the incidence of postoperative complications between total cholecystectomy and subtotal cholecystectomy groups (21% vs 20%, P > 0.05).

CONCLUSION: Neither clinical manifestations and laboratory tests nor radiological methods provide a practical and effective standard in the differential diagnosis between XGC and GBC.

Core tip: Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a destructive inflammatory disease of the gallbladder that could mimic gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) in various ways. The aim of this study was to review and evaluate the diagnostic dilemma of XGC clinically. We concluded that neither clinical manifestations and laboratory tests nor radiological methods provide a practical and effective standard in the differential diagnosis between XGC and GBC. For XGC with suspected GBC, intra-operative frozen section analysis should be performed, and the benign diagnosis indicates that a simple cholecystectomy is appropriate. However, the final diagnosis still depends on the pathology.

- Citation: Deng YL, Cheng NS, Zhang SJ, Ma WJ, Shrestha A, Li FY, Xu FL, Zhao LS. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking gallbladder carcinoma: An analysis of 42 cases. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(44): 12653-12659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i44/12653.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12653

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) is a rare variant of chronic cholecystitis characterized by severe proliferative fibrosis with infiltration of macrophages and foamy cells within the gallbladder wall. This condition is benign in nature but often shows a destructive inflammatory process[1,2]. The inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis cause the asymmetrical thickening of the gallbladder wall and the formation of multiple yellowish-brown nodules, which often extend into the neighboring organs, such as the liver, omentum and duodenum[1,2].

Due to the overlapping features between the two diseases, XGC is frequently misdiagnosed as gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) and usually undergoes an extended radical surgery[3,4]. Sometimes XGC might have a coexistent GBC[5]. Accurate diagnosis is important for the proper surgical management of these patients. To our knowledge, several non-invasive imaging and invasive techniques have been reported to differentiate XGC from GBC[6-10], but the dilemma still exists concerning the differential diagnosis in clinical practice, and the final diagnosis has to be dependent on the histological examination. In the present retrospective study, we analyzed the clinical, radiologic and surgical features of 42 cases of XGC misdiagnosed as GBC to review and evaluate the diagnostic dilemma of XGC clinically.

From July 2008 to June 2014, a total of 142 cases with a pathological diagnosis of XGC were reviewed at our hospital, among which 42 (24 men and 18 women; male-to-female ratio, 4:3; mean age 59.9 years, age range 38-86 years) were misdiagnosed as GBC mainly by the presence of the focal or diffuse thickening of the gallbladder wall, and/or the mass protruding into the lumen based on preoperative radiographs, and/or intra-operative findings. Thirty-eight cases underwent contrast enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT), and 4 cases underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The clinical characteristics, preoperative imaging, intra-operative findings, frozen section (FS) analysis, surgical procedures and histological features of these patients were collected and analyzed.

For each patient, intra-operative findings including inflammation of the gallbladder (atrophy, edema or gangrene), adhesions of the gallbladder to adjacent tissues, thickened gallbladder wall, gallstones, mass lesions, gallbladder internal fistula, enlarged regional lymph nodes and hepatic abscess were observed and recorded. And then, the excised gallbladder was opened along its longitudinal axis and the mucosa was examined macroscopically. If malignancy was suspected, suspicious areas would be labeled by the silk suture and sent for an FS analysis. Briefly, frozen sections of 6-μm thickness were cut using automated devices (Shandon Citadel 2000, Astmoor, United Kingdom). Subsequently, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), and the diagnosis was made by experienced pathologists. Simultaneously the direct contact between surgeons and pathologists was also established.

The gallbladder wall thickness of 1-2 mm was considered as normal, and a wall thickness of 3 mm or more on the imaging or intra-operative findings was considered thickened. GBCs were classified according to the TNM system as proposed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee review board of Sichuan University.

Data were analyzed using the SPSS v13.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States). Statistical comparisons between groups were performed using the Fisher’s exact test. The least significant difference test was performed to compare two groups. A P-value < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

The clinical presentations are summarized in Table 1. The most common syndrome in these 42 patients was chronic cholecystitis, and patients with this clinical syndrome had chronic right upper quadrant (RUQ) pain (61%), abdominal distention (48%), and anorexia (45%). The second most common syndrome was acute cholecystitis, and these patients presented with acute RUQ pain (28%), high grade fever (14%), elevated WBC count (26%), nausea and vomiting (12%). Approximately 21% of the patients presented with mild jaundice, but only two patients were associated with choledocholithiasis. The RUQ mass was palpable in two (5%) patients. Increased CA199 level was observed in 32 (76%) patients and increased carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) level was found only in 6 (14%) patients.

| Variable | No. of patients |

| Presenting signs and symptoms | |

| Pain | 38 (90) |

| Chronic RUQ pain | 26 (61) |

| Acute RUQ pain, Murphy’s sign (+) | 12 (28) |

| Abdominal distention | 20 (48) |

| Anorexia | 19 (45) |

| Jaundice | 9 (21) |

| High grade fever (> 38 °C) | 6 (14) |

| Nausea and vomiting | 5 (12) |

| RUQ mass | 2 (5) |

| Laboratory findings | |

| Elevated WBC count | 11 (26) |

| Elevated blood bilirubin level | 9 (21) |

| Mild | 9 (21) |

| Moderate | 0 |

| Severe | 0 |

| Increased CA199 (> 22 U/mL) | 32 (76) |

| Increased CEA (> 4.0 ng/mL) | 6 (14) |

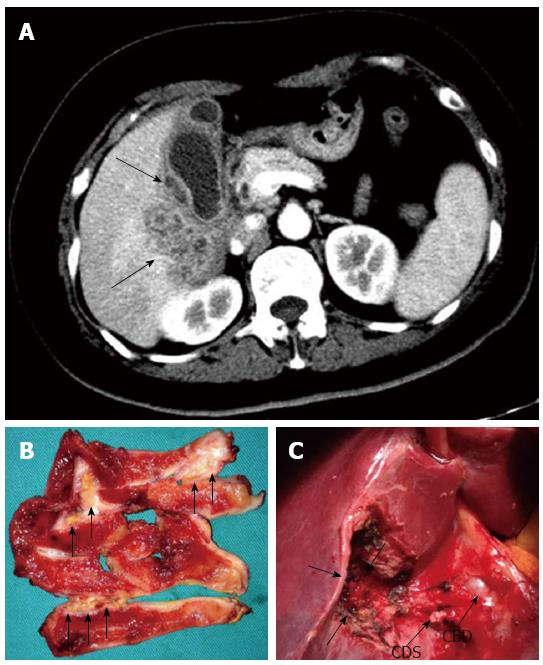

CT or MRI findings in 42 patients are summarized in Table 2. Only 4 (9%) of 42 patients underwent MRI, and studies suggest that the morphological appearance of the GBC in MRI was similar to that obtained by CT[11], so it seemed to be more appropriate to integrate the characteristic MRI findings with CT findings. The presence of a thickened gallbladder wall was noted in all 42 patients, with 64% of the patients having a diffuse thickening. It could also be seen that the majority (83%) of the thickened gallbladder walls showed a heterogeneous enhancement at the luminal surface. Furthermore, 26% of the markedly thickened gallbladder walls were associated with intramural hypo-attenuated nodules. Gallstones were detected in 22 (52%) patients, including two combined common bile duct (CBD) stones. Blurred liver/gallbladder interface was observed in 37 (88%) patients, 29 of whom presented with an abnormal enhancement in the hepatic parenchyma neighboring the gallbladder, which indicated hepatic infiltration. In addition, the infiltration of other adjacent structures could also be noted in 38% of the patients, including the omentum, colon, duodenum, and the antrum of the stomach. Enlarged lymph nodes were noted in 11 (26%) patients.

| Finding | No. of patients |

| Gallstones | 22 (52) |

| Thickened gallbladder wall (> 3 mm) | 42 (100) |

| Diffuse | 27 (64) |

| Focal | 15 (36) |

| Gallbladder distention with pericholecystic fluid | 12 (29) |

| Heterogeneous enhancement of the gallbladder wall | 35 (83) |

| Intramural hypo-attenuated nodules | 11 (26) |

| Pericholecystic infiltration | |

| Blurred liver/gallbladder interface | 37 (88) |

| Abnormal enhancement in hepatic parenchyma neighboring the gallbladder | 29 (69) |

| Infiltration of other adjacent structures | 16 (38) |

| Regional lymph node enlargement | 11 (26) |

Open surgery was planned and performed in all 42 patients. Intra-operative findings confirmed the presence of a thickened gallbladder wall in all patients, and adhesions to the adjacent organs were seen in 40 (95.2%) patients (adhesions to the omentum in 32, the duodenum in 16, the colon in 12, and the stomach in 8). Eleven (26%) patients had the obscure Calot’s triangle anatomy. Twenty patients presented with acute cholecystitis including gallbladder wall edema (n = 15) and gangrenous cholecystitis (n = 5). Gallstones were observed in 23 (55%) patients, including two cases of combined CBD stones. Mass lesions were found in 12 (29%) patients. Other intra-operative findings are shown in Table 3.

| Feature | No. of patients |

| Thickened gallbladder wall | 42 (100) |

| Adhesions | 40 (95) |

| Omentum | 32 (76) |

| Duodena | 16 (38) |

| Colon | 12 (29) |

| Stomach | 8 (19) |

| Obscure Calot’s triangle anatomy | 11 (26) |

| Gallbladder wall edema | 15 (36) |

| Gangrenous cholecystitis | 5 (12) |

| Gallstones | 23 (55) |

| Combined CBD stones | 2 (5) |

| Mass lesions | 12 (29) |

| Enlarged regional lymph nodes | 11 (26) |

| Gallbladder internal fistula | 8 (19) |

| Mirizzi’s syndrome | 4 (10) |

| Cholecystoduodenal fistula | 2 (5) |

| Gallbladder-transverse colon fistula | 2 (5) |

| Hepatic abscess | 3 (7) |

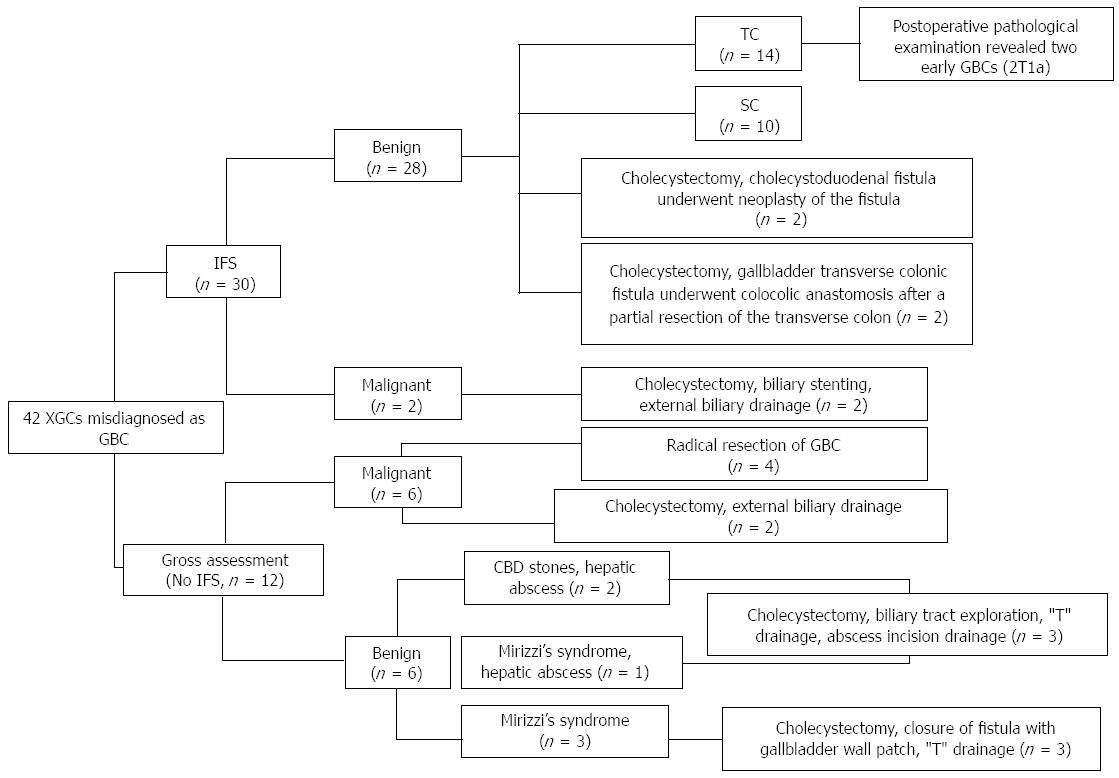

The surgical procedures for the 42 XGC cases are shown in Figure 1. Intra-operative FS analysis was performed in 30 patients, revealing 28 benign and 2 malignant gallbladder lesions. Among 28 benign lesions, total cholecystectomy (TC) was performed on 14 patients and subtotal cholecystectomy (SC) on 10 patients. For two GBCs, only an external biliary drainage was carried out. Twelve cases of XGC did not undergo intra-operative FS analysis, whereas 6 “GBCs” were diagnosed by surgeon’s macroscopic examination during surgery, and thereafter 4 patients received “radical resection of GBC”, with 2 patients receiving an external biliary drainage. Another 6 patients were considered to be suffering from benign gallbladder disease by surgeon, including a combined CBD stone, hepatic abscess and Mirizzi’s syndrome. Ultimately, specimens from all the 42 patients were examined pathologically after operation. Of the 14 patients who underwent TC, only 2 were definitively diagnosed with coexisting early GBC (T1a).

Of the 42 XGC cases reviewed, 12 patients underwent TC. SC was carried out only in 10 patients, leaving a part of the posterior wall adherent to the hepatic bed, or a part of the hartmann sac or the gallbladder neck, due to obscure Calot’s triangle anatomy and/or gangrenous cholecystitis with severe fibrotic adhesions and/or the high risk gallbladder bed in cirrhotic patients. Postoperative complications are summarized in Table 4. Comparison between the two groups showed no statistical difference in the incidence rates of complications (21% vs 20%, P > 0.05). However, there was one case of common bile duct injury which underwent a primary repair and “T-tube” drainage, and one case of duodenal injury repaired by omental patch and suture repair for the TC group, while there was no serious complication observed in the SC group. No deaths occurred in either group.

| Complication | TC (n = 14) | SC (n = 10) | P value | Significance |

| Surgical site infection | 1 (7) | 1 (10) | 1.000 | NS |

| Retained stone | 0 | 1 (10) | 0.417 | NS |

| Bile duct injury | 1 (7) | 0 | 1.000 | NS |

| Duodenal injury | 1 (7) | 0 | 1.000 | NS |

| Controlled bile leakage | 0 | 0 | - | NS |

| Biliperitoneum | 0 | 0 | - | NS |

| Hemoperitoneum | 0 | 0 | - | NS |

| Mortality | 0 | 0 | - | NS |

| Morbidity | 3 (21) | 2 (20) | 1.000 | NS |

The pathogenesis of XGC is not fully understood till now. The presence of gallstones and biliary obstruction might play an important role, which causes the extravasation of the bile into the gallbladder wall via ruptured Rokitansky-Aschoff sinuses and/or ulcers of the surface mucosa[1,2]. Clinically, XGC not only often imitates GBC in various ways leading to the misdiagnosis of GBC, but it could also coexist with GBC[3-10]. In our study, 42 (29.6%) out of 142 cases of XGC were misdiagnosed as GBC either preoperatively or intra-operatively, but only 4 (9.5%) cases were corroborated by pathology, indicating a high rate of misdiagnosis. Only 4 (2.8%) of 142 XGC cases had the coexisting GBC.

Of these 42 XGC cases misdiagnosed as GBC, no specific symptoms were observed. These symptoms could be grouped roughly into three clinical syndromes. The first and most common syndrome was chronic cholecystitis, followed by acute cholecystitis. The third syndrome was a biliary-tract disease which mainly included jaundice, RUQ pain, and high grade fever. These vague and nonspecific symptoms are just similar to those of GBC[11], and usually not helpful in the differentiation of these two conditions. Of all the cases of XGC, 9 presented with mild jaundice in our study, which indicated that mild jaundice may be of important significance in differentiating XGC from GBC with moderate or severe jaundice. Increased presence of tumor markers such as CEA and CA 199 should raise suspicions of GBC. Some studies showed that the increased CA199 level (> 20 U/mL) had a 79.4% sensitivity and a 79.2% specificity, and the increased CEA level (> 4.0 ng/mL) had a 93% specificity, but only a 50% sensitivity[11,12]. However, the increased CA199 and CEA levels (76% and 14%, respectively) were also present in 42 XGC cases, which proved to be futile and of no clinical significance in the differential diagnosis of XGC from GBC.

Radiology was the only helpful modality to make a differential diagnosis between XGC and GBC. Several imaging studies have shown relative specificities in some CT or MRI features for the diagnosis of XGC, mainly including intramural hypo-attenuated nodules within the thickened walls, homogeneous enhancement of the mucosa, and absence of macroscopic hepatic invasion[6-10]. Combination of certain imaging findings could even provide excellent accuracy for the differentiation of both the conditions[7,8]. Despite the radiographic progressions in the XGC diagnosis, 29.6% of XGC cases were misdiagnosed as GBC by radiologists in our study. By analyzing imaging features of these 42 cases, the intramural hypo-attenuated nodule within the thickened wall was observed only in 26% of the cases, but abnormal enhancement in hepatic parenchyma neighboring the gallbladder was observed in 69% of cases, which indicated hepatic invasion. The infiltration of other adjacent structures and enlarged lymph nodes were also noted in several cases. These above imaging features were highly suggestive of GBC rather than XGC. Except for the concomitant liver metastases, there was too much overlap of the imaging findings between XGC and GBC to reliably differentiate between two entities. Furthermore, the rarity of XGC and the possibility of the coexisting GBC also contributed to the difficulty of the differential diagnosis. Therefore, pathological examination was necessary for the definitive diagnosis especially to rule out GBC.

Previously, needle biopsy guided by US or CT has been reported to be performed safely and accurately in differentiating XGC from GBC[13]. But this practice was solely dependent on both the operator’s experience in obtaining the samples and a high quality pathology service. During surgery, if GBC could not be excluded, intra-operative FS analysis is worth recommending regardless of the possibilities of false-negative results. In our study, 30 gallbladder specimens were sent for an intra-operative FS analysis, showing GBC in 2 patients (the diagnosis was confirmed by pathology), and inflammatory lesions in 28 (but 2 of 28 patients had pathologically confirmed T1a GBC). The diagnostic accuracy of FS analysis was calculated to be around 93% (Table 5). The remaining 12 XGC cases did not undergo intra-operative FS analysis, and 6 of them were identified as GBC and the other 6 cases as benign lesions only by surgeon’s macroscopic examination. However, 6 “GBCs” were not further confirmed by the final pathologic examination, showing that the accuracy of surgeon’s macroscopic diagnosis of GBC in XGC was only 50% (Table 6). Although 2 patients had early GBCs (T1a) missed on FS analysis (underwent cholecystectomy alone), all 30 patients still received the appropriate surgical treatment on the basis of FS analysis results rather than pathologic examination[11,14]. However, 6 “GBCs” misdiagnosed by surgeons underwent aggressive surgical treatment, which may have been avoided if intra-operative FS analysis was also conducted.

| Frozen section diagnosis | Definitive pathological diagnosis | ||

| Cancer | Benign | Total | |

| Cancer | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Benign | 2 | 26 | 28 |

| Total | 4 | 26 | 30 |

| Surgeon’s macroscopic diagnosis | Definitive pathological diagnosis | ||

| Cancer | Benign | Total | |

| Cancer | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Benign | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Total | 0 | 12 | 12 |

Generally, a simple cholecystectomy is enough for XGC[1,2,15]. Sometimes, a complete resection of the gallbladder was not always judicious especially due to the obscure Calot’s triangle anatomy and/or high risk gallbladder bed in cirrhotic patients. SC was a practical alternative to TC, leaving part of the hartmann sac, gallbladder neck, and part of the posterior wall adherent to the hepatic bed[16]. Table 4 shows that no statistical difference was encountered in the incidence of postoperative complications between the TC and SC groups, although two serious complications (common bile duct injury and duodenal injury) occurred in the TC group. SC should be a part of a surgeon’s armamentarium in complicated XGC. However, coexisting GBC should be ruled out before SC was performed in XGC. No association with the GBC could be established in our 42 XGC cases. Therefore, an intra-operative FS analysis should be obtained in patients with suspected GBC, and the benign diagnosis indicates a more conservative surgical approach (Figure 2). However, we should always remember that a simple cholecystectomy, either TC or SC, could result in denying a patient the optimal surgical approach due to the existence of a false-negative result in FS analysis. If FS diagnosis was not confirmed by the final pathological examination, re-operation may be inevitable according to the oncologic point of view.

In conclusion, there was a significant overlap in various ways in clinical practice between XGC and GBC. Neither clinical manifestations, nor laboratory tests or radiological methods could provide an effective and practical standard in characterizing the differential diagnosis, and the occasional coexistence of two entities further resulted in a diagnostic confusion. The definitive diagnosis by all standards will still be dependent on the pathology. For XGC with suspected GBC, intra-operative FS analysis had a diagnostic accuracy of 93%, and the benign diagnosis indicated that a simple cholecystectomy was enough, i.e., either TC or SC. Nevertheless, the benign diagnosis must be confirmed by a pathological examination, or else re-operation may be inevitable according to the oncologic point of view.

Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis (XGC) was a destructive inflammatory disease of the gallbladder that could mimic gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) in various ways including clinical manifestations, imaging and intra-operative findings, and even coexisted with GBC, leading to a diagnostic dilemma.

Due to the overlapping features between the two diseases, XGC is frequently misdiagnosed as GBC and usually undergoes an extended radical surgery. Sometimes XGC might have a coexistent GBC. Accurate diagnosis is important for the proper surgical management of these patients. Several non-invasive imaging and invasive techniques have been reported to differentiate XGC from GBC, but the dilemma still exists concerning the differential diagnosis in clinical practice, and the final diagnosis has to be dependent on the histological examination.

There is a significant overlap in various ways in clinical practice between XGC and GBC. Neither clinical manifestations and laboratory tests nor radiological methods provide a practical and effective standard in the differential diagnosis between XGC and GBC. Moreover, the occasional coexistence of two entities further results in diagnostic confusion.

For XGC with suspected GBC, intra-operative frozen section analysis had a diagnostic accuracy of 93%, and the benign diagnosis indicates that a simple cholecystectomy is enough, i.e., either total cholecystectomy or subtotal cholecystectomy. Nevertheless, the benign diagnosis must be confirmed by a pathological examination, or else re-operation may be inevitable according to the oncologic point of view.

XGC is a rare variant of chronic cholecystitis characterized by severe proliferative fibrosis with infiltration of macrophages and foamy cells within the gallbladder wall. This condition is benign in nature but often shows a destructive inflammatory process. The inflammatory infiltration and fibrosis cause the asymmetrical thickening of the gallbladder wall and the formation of multiple yellowish-brown nodules, which often extend into the neighboring organs, such as the liver, omentum and duodenum.

This study is an interesting analysis for a rare inflammatory process mimicking gallbladder carcinoma.

P- Reviewer: Mastoraki A S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Hale MD, Roberts KJ, Hodson J, Scott N, Sheridan M, Toogood GJ. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: a European and global perspective. HPB (Oxford). 2014;16:448-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kwon AH, Matsui Y, Uemura Y. Surgical procedures and histopathologic findings for patients with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:204-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pinocy J, Lange A, König C, Kaiserling E, Becker HD, Kröber SM. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis resembling carcinoma with extensive tumorous infiltration of the liver and colon. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Spinelli A, Schumacher G, Pascher A, Lopez-Hanninen E, Al-Abadi H, Benckert C, Sauer IM, Pratschke J, Neumann UP, Jonas S. Extended surgical resection for xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis mimicking advanced gallbladder carcinoma: A case report and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2293-2296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kwon AH, Sakaida N. Simultaneous presence of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis and gallbladder cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:703-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Goshima S, Chang S, Wang JH, Kanematsu M, Bae KT, Federle MP. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: diagnostic performance of CT to differentiate from gallbladder cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2010;74:e79-e83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shetty GS, Abbey P, Prabhu SM, Narula MK, Anand R. Xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: sonographic and CT features and differentiation from gallbladder carcinoma: a pictorial essay. Jpn J Radiol. 2012;30:480-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhao F, Lu PX, Yan SX, Wang GF, Yuan J, Zhang SZ, Wang YX. CT and MR features of xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis: an analysis of consecutive 49 cases. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1391-1397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chang BJ, Kim SH, Park HY, Lim SW, Kim J, Lee KH, Lee KT, Rhee JC, Lim JH, Lee JK. Distinguishing xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis from the wall-thickening type of early-stage gallbladder cancer. Gut Liver. 2010;4:518-523. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Agarwal AK, Kalayarasan R, Javed A, Sakhuja P. Mass-forming xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis masquerading as gallbladder cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:1257-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC, Sharma ID. Carcinoma of the gallbladder. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:167-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 480] [Cited by in RCA: 465] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Strom BL, Maislin G, West SL, Atkinson B, Herlyn M, Saul S, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, Rios-Dalenz J, Iliopoulos D, Soloway RD. Serum CEA and CA 19-9: potential future diagnostic or screening tests for gallbladder cancer? Int J Cancer. 1990;45:821-824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hijioka S, Mekky MA, Bhatia V, Sawaki A, Mizuno N, Hara K, Hosoda W, Shimizu Y, Tamada K, Niwa Y. Can EUS-guided FNA distinguish between gallbladder cancer and xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis? Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:622-627. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wakai T, Shirai Y, Yokoyama N, Nagakura S, Watanabe H, Hatakeyama K. Early gallbladder carcinoma does not warrant radical resection. Br J Surg. 2001;88:675-678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 15. | Srinivas GN, Sinha S, Ryley N, Houghton PW. Perfidious gallbladders - a diagnostic dilemma with xanthogranulomatous cholecystitis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2007;89:168-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Elshaer M, Gravante G, Thomas K, Sorge R, Al-Hamali S, Ebdewi H. Subtotal cholecystectomy for “difficult gallbladders”: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2015;150:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |