Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12635

Peer-review started: May 27, 2015

First decision: June 19, 2015

Revised: July 15, 2015

Accepted: September 30, 2015

Article in press: September 30, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 185 Days and 15.3 Hours

AIM: To identify the actual clinical management and associated factors of delayed perforation after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD).

METHODS: A total of 4943 early gastric cancer (EGC) patients underwent ESD at our hospital between January 1999 and June 2012. We retrospectively assessed the actual management of delayed perforation. In addition, to determine the factors associated with delayed perforation, after excluding 123 EGC patients with perforations that occurred during the ESD procedure, we analyzed the following clinicopathological factors among the remaining 4820 EGC patients by comparing the ESD cases with delayed perforation and the ESD cases without perforation: age, sex, chronological periods, clinical indications for ESD, status of the stomach, location, gastric circumference, tumor size, invasion depth, presence/absence of ulceration, histological type, type of resection, and procedure time.

RESULTS: Delayed perforation occurred in 7 (0.1%) cases. The median time until the occurrence of delayed perforation was 11 h (range, 6-172 h). Three (43%) of the 7 cases required emergency surgery, while four were conservatively managed without surgical intervention. Among the 4 cases with conservative management, 2 were successfully managed endoscopically using the endoloop-endoclip technique. The median hospital stay was 18 d (range, 15-45 d). There were no delayed perforation-related deaths. Based on a multivariate analysis, gastric tube cases (OR = 11.0; 95%CI: 1.7-73.3; P = 0.013) were significantly associated with delayed perforation.

CONCLUSION: Endoscopists must be aware of not only the identified factors associated with delayed perforation, but also how to treat this complication effectively and promptly.

Core tip: In this study, delayed perforation occurred in 0.1% (7 cases) of 4943 early gastric cancer patients undergoing endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD); 43% (3 cases) of these cases required emergency surgery. This study also showed that the gastric tube was an independent risk factor associated with delayed perforation. This study is significant because it clarified both the clinical management and risk factors of delayed perforation based on data from a large series of consecutive patients undergoing ESD. Endoscopists must be aware of not only the identified factors associated with delayed perforation, but also how to treat this complication effectively and promptly.

- Citation: Suzuki H, Oda I, Sekiguchi M, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Nakajima T, Saito Y. Management and associated factors of delayed perforation after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(44): 12635-12643

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i44/12635.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12635

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is widely used in East Asia (e.g., Japan and Korea) as an initial treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC) with a negligible risk of lymph node (LN) metastasis, even for cases that involve large and ulcerative lesions[1-4]. The therapeutic outcomes of gastric ESD are excellent; however, there are still cases of various complications, such as bleeding and perforation[5,6]. ESD procedure-related perforations can be subdivided into perforations that occur during gastric ESD and delayed perforations occurring after the completion of gastric ESD. Most perforations occur during gastric ESD, and the risk of perforation reportedly ranges from 1.2% to 9.6% for gastric ESD[5-12]. The majority of perforation cases can be treated conservatively using complete endoscopic closure with endoclips[5,6,13]. In contrast, delayed perforation is a rare (with an incidence of 0.43% to 0.45%) but serious complication that sometimes requires emergent surgery[6,14-20]. Under these circumstances, the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation induced by gastric ESD should be clarified to minimize its incidence and to treat this complication effectively and promptly. Although several reports have described delayed perforation after gastric ESD, no published report has thoroughly evaluated the various factors associated with delayed perforation based on data from a large series of consecutive EGC patients undergoing ESD[14-20]. Therefore, we attempted to identify the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation induced by ESD for EGC based on our extensive clinical experience.

A total of 4943 EGC patients (male:female ratio, 3.9:1; median age, 69 years; range, 27-96 years) underwent ESD at our hospital between January 1999 and June 2012. The clinicopathological findings of these 4943 EGC patients are shown in Table 1. In our hospital, according to the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guideline, ESD is generally performed based on two independent sets of clinical indications: absolute indications for standard treatment, and expanded indications for investigational treatment[3]. Furthermore, ESD is also performed for a small number of patients with locally recurrent EGC or EGC lesions outside the clinical indications for ESD, particularly gastric tube cases, because the mortality rate for surgical resection is remarkably high[21-24]. The definitions for the characteristics of EGC lesions, such as status of the stomach (normal stomach/remnant stomach after a gastrectomy/gastric tube after an esophagectomy), lesion location (upper/middle/lower third of the stomach), gastric circumference (greater curvature/lesser curvature/anterior wall/posterior wall), tumor size, depth of invasion [mucosa (M)/submucosa (SM)], presence of ulcerations, and histological type (differentiated-type/undifferentiated-type), were based on the Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma and the Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines[3,25]. The term “gastric tube” refers to a stomach conduit that has been pulled up into the thorax for use as an esophageal substitute after an esophagectomy[23,24]. The histological type was defined according to the major histological features of the lesion. Differentiated-type adenocarcinoma included tubular adenocarcinoma and papillary adenocarcinoma, while undifferentiated-type adenocarcinoma included poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, signet-ring cell adenocarcinoma and mucinous adenocarcinoma.

| Clinicopathological finding | n (%) |

| Age (yr) | |

| median (range) | 69 (27-96) |

| < 70 | 2608 (52.8) |

| ≥ 70 | 2335 (47.2) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 3930 (80.0) |

| Female | 1013 (20.0) |

| Chronological periods | |

| 1st period: 1999-2005 | 2285 (46.2) |

| 2nd period: 2006-2012 | 2658 (53.8) |

| Clinical indications | |

| Absolute indications | 2884 (58.3) |

| Expanded indications | 1737 (35.1) |

| Locally recurrent EGC | 141 (2.9) |

| Outside indications | 181 (3.7) |

| Stomach status | |

| Normal stomach | 4704 (95.2) |

| Remnant stomach | 152 (3.1) |

| Gastric tube | 87 (1.7) |

| Location | |

| Upper | 904 (18.3) |

| Middle | 2100 (42.5) |

| Lower | 1939 (39.2) |

| Circumference | |

| Greater curvature | 807 (16.3) |

| Lesser curvature | 2005 (40.6) |

| Anterior wall | 963 (19.5) |

| Posterior wall | 1168 (23.6) |

| Size (mm) | |

| median (range) | 15 (0.4-120) |

| ≤ 20 | 3457 (69.9) |

| > 20 | 1486 (30.1) |

| Depth of invasion | |

| M | 4075 (82.4) |

| SM | 868 (17.6) |

| Ulceration | |

| Absent | 4073 (82.4) |

| Present | 870 (17.6) |

| Histological type | |

| Differentiated | 4581 (92.7) |

| Undifferentiated | 362 (7.3) |

| Type of resection | |

| En bloc resection | 4859 (98.3) |

| Piecemeal resection | 84 (1.7) |

| Procedure time (h) | |

| mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 1.1 |

| < 2 | 3811 (77.1) |

| ≥ 2 | 1132 (22.9) |

The ESD procedure began with the identification of the lesion and the marking of dots at a distance of about 5 mm outside of the lesion. After submucosal injection using a saline solution or sodium hyaluronate (MucoUp; Johnson & Johnson Corp., Tokyo, Japan) with epinephrine, a 1- to 2-mm precut was made with an electrosurgical needle knife (KD-1L-1; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) or the Dual knife (KD-650Q; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan), followed by a circumferential mucosal incision outside the marking dots with an insulation-tipped (IT) diathermy knife (KD-610L; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) or IT knife 2 (KD-611L; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). The submucosal layer was then dissected using an IT knife or an IT knife 2 after an additional submucosal injection. Cases with bleeding during or after the ESD procedure were controlled by coagulating the bleeding vessels with the IT knife itself and/or hemostatic forceps [Coagrasper (FD-410LR; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) and Radial Jaw hot biopsy forceps (Boston Scientific Japan, Tokyo, Japan)], or by grasping them with endoclips. The set-up for the high-frequency generators for ESD along with the IT knife for early gastric cancer (ICC200 Erbe Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany, ESG100 Olympus Medical and VIO300D Erbe Elektromedizin, Tübingen, Germany) is shown in Table 2. The risks and benefits of ESD were thoroughly explained to each patient, and written informed consent was obtained from them in accordance with our institutional protocols prior to treatment.

| Procedure | Device | Mode | Output |

| ICC200 | |||

| Marking | Needle knife | Forced coag | 20W |

| Precutting | Needle knife | ENDO CUT | Effect 3, 80W |

| Mucosal incision | IT knife | ENDO CUT | Effect 3, 80W |

| Needle knife | |||

| Submucosal dissection | IT knife | ENDO CUT | Effect 3, 80W |

| Forced coag | 50W | ||

| Needle knife | ENDO CUT | Effect 3, 80W | |

| Forced coag | 50W | ||

| Endoscopic hemostasis | IT knife | Forced coag | 50W |

| Needle knife | |||

| Hot biopsy | Soft coag | 80W | |

| Coagrasper | |||

| ESG100 | |||

| Marking | Needle knife | Forced coag 1 | 20W |

| Precutting | Needle knife | Pulse cut slow | 40W |

| Mucosal incision | IT knife | Pulse cut slow | 40W |

| Needle knife | |||

| Submucosal dissection | IT knife | Pulse cut slow | 40W |

| Forced coag 2 | 50W | ||

| Needle knife | Pulse cut slow | 40W | |

| Forced coag 2 | 50W | ||

| Endoscopic hemostasis | IT knife | Forced coag 2 | 50W |

| Needle knife | |||

| Hot biopsy | Soft coag | 80W | |

| Coagrasper | |||

| VIO300D | |||

| Marking | Needle knife | Swift coag | Effect 2, 50W |

| Precutting | Needle knife | ENDO CUT I | Effect 2, CUT duration 2, CUT interval 3 |

| Mucosal incision | IT knife | ENDO CUT I or Q | Effect 2, CUT duration 2, CUT interval 3 |

| DRY CUT | Effect 4, 50W | ||

| Needle knife | ENDO CUT I | Effect 2, CUT duration 2, CUT interval 3 | |

| DRY CUT | Effect 4, 50W | ||

| Submucosal dissection | IT knife | ENDO CUT I or Q | Effect 2, CUT duration 2, CUT interval 3 |

| DRY CUT | Effect 4, 50W | ||

| Swift coag | Effect 5, 50W | ||

| Needle knife | ENDO CUT I | Effect 2, CUT duration 2, CUT interval 3 | |

| DRY CUT | Effect 4, 50W | ||

| Swift coag | Effect 5, 50W | ||

| Endoscopic hemostasis | IT knife | Swift coag | Effect 5, 50W |

| Needle knife | |||

| Hot biopsy | Soft coag | Effect 5, 80W | |

| Coagrasper | |||

The procedure time was defined as the time from circumferential marking around the lesion to the completion of the ESD procedure. An en bloc resection was defined as a one-piece resection, and a piecemeal resection was defined as the removal of a lesion in more than one piece[3,25].

We retrospectively assessed the incidence of delayed perforation and the actual clinical management of this complication, including the need for emergency surgery, the methods of conservative management, and the median hospital stay. For the cases with delayed perforation requiring emergency surgery, the reason for the emergency surgery was also clarified. Finally, to determine the factors associated with delayed perforation induced by gastric ESD, after excluding 123 (2.5%) EGC patients with perforations that occurred during the ESD procedure, we retrospectively analyzed the following clinicopathological factors among the remaining 4820 EGC patients by comparing the ESD cases with delayed perforation with the ESD cases without perforation: age (< 70 years vs≥ 70 years), sex (male vs female), chronological periods (1st period: 1999-2005 vs 2nd period: 2006-2012), clinical indications for ESD (absolute indications vs expanded indications vs locally recurrent EGC vs outside indications), status of the stomach (normal stomach vs remnant stomach after gastrectomy vs gastric tube after esophagectomy), lesion location (upper/middle vs lower), gastric circumference (greater curvature vs lesser curvature vs anterior wall vs posterior wall), tumor size (≤ 20 mm vs > 20 mm), depth of invasion (M vs SM), presence/absence of ulceration, histological type (differentiated-type vs undifferentiated-type), type of resection (en bloc resection vs piecemeal resection), and procedure time (< 2 h vs≥ 2 h).

Delayed perforation was identified by the sudden appearance of symptoms of peritoneal or mediastinal pleura irritation (gastric tube case) after the completion of gastric ESD, with free air visible on X-ray or computed tomography (CT) images and/or with a gross defect observed endoscopically, although endoscopically visible perforations did not occur during the ESD procedure and no remarkable clinical symptoms were observed, suggesting perforation, just after the ESD procedures.

The Fisher exact test or the χ2 test was used for the univariate analyses to assess the above-mentioned clinicopathological factors by comparing the ESD cases with delayed perforation with the ESD cases without perforation. We performed a multivariate analysis for clinicopathological factors that were significant in univariate analyses. A logistic regression analysis was used for the multivariate analysis. All the statistical analyses were performed using the statistical analysis software SPSS, version 20 (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Delayed perforation occurred in 7 (0.1%) ESD cases (Table 3). The median time until the occurrence of delayed perforation was 11 h (range, 6-172 h). As for the management of the delayed perforations, 3 (43%) of the 7 delayed perforation cases underwent emergency surgery, while 4 were conservatively managed with nasogastric tube placement, fasting, and the use of intravenous antibiotics and proton pump inhibitors. Two of the 3 patients who required emergency surgery received an omentoplasty or simple closure of the perforation hole; however, one patient underwent a distal gastrectomy because the ESD was evaluated as a non-curative resection. The reason for the emergency surgery in these three cases was panperitonitis with remarkable clinical symptoms, such as diffuse and severe tenderness and/or defense musculaire. Among the 4 cases treated with conservative management, 2 were successfully managed endoscopically using an endoloop-endoclip technique[23,26]. In this technique, the endoloop snare was anchored with some clips to the normal mucosa around the delayed perforation defect[26]. The endoloop snare was tightened slightly, approximating the borders of the defect. Finally, additional clips were placed to achieve complete closure. The median hospital stay in the delayed perforation cases was 18 d (range, 15-45 d). No delayed perforation-related deaths occurred in this series.

| Case | Age (yr) | Sex | Stomach status | Time until the occurrence of delayed perforation (h) | Panperitonitis or severe mediastinitis | Management of delayed perforation | Hospital stay (d) |

| 1 | 68 | Male | Gastric tube | 11 | Absent | Conservative management | 45 |

| 2 | 75 | Male | Normal stomach | 35 | Absent | Conservative management | 18 |

| 3 | 80 | Male | Normal stomach | 6 | Absent | Conservative management with endoloop-endoclip technique | 18 |

| 4 | 64 | Female | Gastric tube | 7 | Absent | Conservative management with endoloop-endoclip technique | 25 |

| 5 | 73 | Male | Normal stomach | 9 | Present (Panperitonitis) | Emergency surgery | 15 |

| 6 | 62 | Female | Normal stomach | 27 | Present (Panperitonitis) | Emergency surgery | 18 |

| 7 | 56 | Female | Normal stomach | 172 | Present (Panperitonitis) | Emergency surgery | 15 |

Based on univariate analyses, outside clinical indications, gastric tube cases, location in the upper/middle third of the stomach, and procedure time ≥ 2 h were significantly associated with a delayed perforation (Table 4). No significant difference between the rates of delayed perforation was observed when the absolute indications (0.1%) and expanded indications (0.1%) were applied. Using a multivariate analysis for these cases, gastric tube cases (OR = 11.0; 95%CI: 1.7-73.3; P = 0.013) were found to be significantly associated with delayed perforation (Table 4).

| Clinicopathological finding | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis, OR (95%CI), P value | ||

| ESD cases without perforation (n = 4813) | ESD cases with delayed perforation (n = 7) | P value | ||

| Age (yr) | 1.00 | - | ||

| < 70 | 2538 (99.8) | 4 (0.2) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 2275 (99.9) | 3 (0.1) | ||

| Sex | 0.16 | - | ||

| Male | 3828 (99.9) | 4 (0.1) | ||

| Female | 985 (99.7) | 3 (0.3) | ||

| Chronological periods | 1.00 | - | ||

| 1st period: 1999-2005 | 2194 (99.9) | 3 (0.1) | ||

| 2nd period: 2006-2012 | 2619 (99.8) | 4 (0.2) | ||

| Clinical indications | 0.02 | NS | ||

| Outside indications | 169 (98.8) | 2 (1.2) | ||

| Other indications1 | 4644 (99.9) | 5 (0.1) | ||

| Stomach status | 0.006 | 11.0 (1.7-73.3), 0.013 | ||

| Normal stomach/Remnant stomach | 4732 (99.9) | 5 (0.1) | ||

| Gastric tube | 81 (97.6) | 2 (2.4) | ||

| Location | 0.047 | NS | ||

| Upper/Middle | 2894 (99.8) | 7 (0.2) | ||

| Lower | 1919 (100) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Circumference | 0.09 | - | ||

| Greater curvature | 774 (99.6) | 3 (0.4) | ||

| Others2 | 4039 (99.9) | 4 (0.1) | ||

| Size (mm) | 0.43 | - | ||

| ≤ 20 | 3395 (99.9) | 4 (0.1) | ||

| > 20 | 1418 (99.8) | 3 (0.2) | ||

| Depth of invasion | 0.34 | - | ||

| M | 3988 (99.9) | 5 (0.1) | ||

| SM | 825 (99.8) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Ulceration | 0.34 | - | ||

| Absent | 3982 (99.9) | 5 (0.1) | ||

| Present | 831 (99.8) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Histological type | 0.09 | - | ||

| Differentiated | 4466 (99.9) | 5 (0.1) | ||

| Undifferentiated | 347 (99.4) | 2 (0.6) | ||

| Type of resection | 1.00 | - | ||

| En bloc resection | 4743 (99.9) | 7 (0.1) | ||

| Piecemeal resection | 70 (100) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Procedure time (h) | 0.046 | NS | ||

| < 2 | 3758 (99.9) | 3 (0.1) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 1055 (99.6) | 4 (0.4) | ||

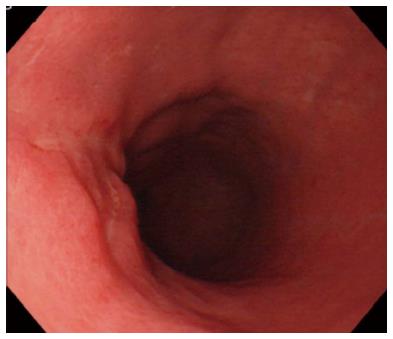

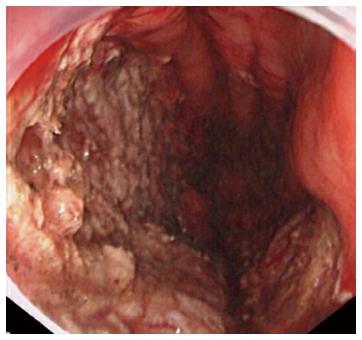

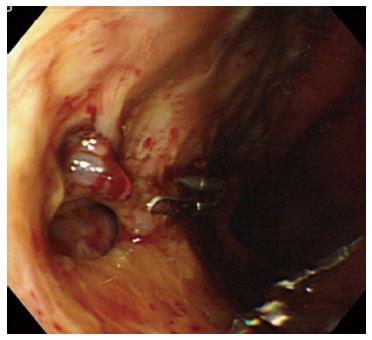

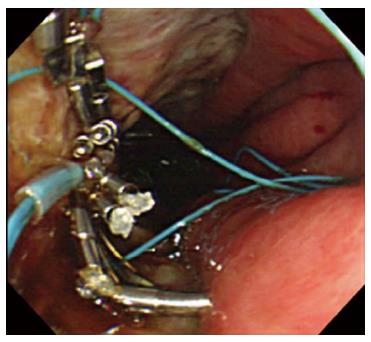

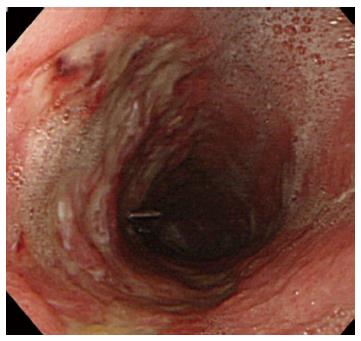

A representative case (Case 4 in Table 3) with delayed perforation is shown in Figures 1-5. A 64-year-old woman underwent surveillance endoscopy after an esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. The endoscopy showed a superficial depressed EGC lesion, 33 mm in size, at the greater curvature of the upper gastric body of the gastric tube (Figure 1). The estimated tumor depth was the submucosa, and a biopsy revealed a poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma. ESD was performed for this lesion as a diagnostic procedure, and an en bloc resection with negative margins was achieved without any complications. As for the mucosal defect just after the completion of ESD, the size of the defect was 60 mm, and the circumferential extent of the defect was one half of the lumen of the gastric tube. At the proximal edge of the ulceration, severe damage to the surface of the muscularis propria as a result of electrical cautery was seen, but no remarkable clinical symptoms, suggesting perforation, were observed (Figure 2). Seven hours after the ESD, a delayed perforation occurred with chest pain (Figure 3). However, this patient did not develop severe mediastinitis, so endoscopic closure using the endoloop-endoclip technique was attempted and successfully performed (Figure 4). In detail, the endoloop snare was anchored with some clips to the normal mucosa around the delayed perforation defect[23,26]. The endoloop snare was tightened slightly, which approximated the borders of the defect. To achieve complete closure, two endoloop snares with additional clips were needed. The delayed perforation had almost completely healed 15 d after ESD (Figure 5) and finally, the patient was conservatively managed and was discharged 25 d after ESD.

Delayed perforation is reported to be a rare (incidence of 0.43% to 0.45%) but serious complication induced by gastric ESD that can sometimes require emergent surgery[6,14-20]. Although several reports have described delayed perforation after gastric ESD, no published report has thoroughly evaluated the various factors that are associated with delayed perforation based on data from a large series of consecutive EGC patients undergoing ESD[6,14-20]. Therefore, the present study is significant because it clarified both the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation induced by ESD for EGC based on data from a large series of consecutive patients undergoing gastric ESD.

In the present study, delayed perforation after gastric ESD occurred in 7 (0.1%) ESD cases, and 3 (43%) of these 7 cases required emergency surgery. Another report from Hanaoka et al[14] described 6 (0.45%) cases with delayed perforation among 1329 EGC lesions, and 5 (83%) of these 6 cases underwent emergency surgery. In addition, Kato et al[16] reported 2 (0.43%) cases of delayed perforation occurring after the completion of ESD among 468 cases of gastric non-invasive neoplasia, both of which required emergency surgery. Several case reports of delayed perforation after gastric ESD that were successfully managed conservatively have also been reported[15,17,18,20]. Thus, although a small number of cases of delayed perforation might be successfully managed conservatively (9 among 21 delayed perforation patients, including 14 patients in previous reports[14-20] and our 7 patients, were successfully managed conservatively), we need to remember that in delayed perforation cases, emergency surgery may be required with a high probability and conservative management might not always be feasible. In the near future, the establishment of effective conservative treatments may reduce the rate of delayed perforation cases requiring emergency surgery[20]. The early recognition of the onset of delayed perforation after the sudden appearance of symptoms of peritoneal or mediastinal pleura irritation (gastric tube cases) within 24 h after gastric ESD followed by prompt conservative treatment may be useful for avoiding emergency surgery. In the case of delayed perforation without any findings of panperitonitis or severe mediastinitis (gastric tube cases), the endoloop-endoclip technique under CO2 insufflation might make it possible to close defects of the gastric wall caused by delayed perforation in a conservative manner, as in our representative case[23,26,27]. CO2 insufflation has increasingly been used instead of air insufflation to minimize pneumoperitoneum caused by perforation[27].

The results of the present study also showed that gastric tube cases were an independent risk factor associated with delayed perforation after ESD, based on a large consecutive series of EGC patients. Hanaoka et al[14] reported that 5 out of 6 delayed perforations occurred in the upper third of the stomach; however, this report represented a case series of delayed perforations without any assessment of the risk factors associated with delayed perforation by comparing the ESD cases with delayed perforation with ESD cases without perforation. The reason for the high frequency of delayed perforations in the gastric tube was uncertain, but reduced vascular circulation of the reconstructed gastric tube may have resulted in slower ESD ulcer healing[23]. In addition, Hanaoka et al[14] reported that the mechanism of delayed perforation was thought to be due to electrical cautery during the submucosal dissection or repeated coagulation causing ischemic changes to the gastric wall, resulting in necrosis. Furthermore, Onogi et al[28] reported the existence of a “transmural air leak” after gastric ESD, as detected by a CT examination. In the present study, we cannot rule out the possible existence of severe damage to the surface of the muscularis propria with a transmural air leak, since we did not perform a CT examination in most of the cases undergoing gastric ESD. Thus, there might be a possibility of developing delayed perforation from severe damage to the surface of the muscularis propria with transmural air leaks after the ESD procedure. More recently, the feasibility and effectiveness of ESD for gastric tube cancer after esophagectomy have been reported[23,24]. Thus, awareness of this finding is important before the widespread use of this treatment, and in cases of ESD for gastric tube cancer, it might be better to avoid excessive electrical cautery during submucosal dissection or repeated coagulation so as to prevent delayed perforation.

Our study had several limitations. First, the results of the present study were based on retrospective assessments of the medical records of patients with gastric ESD, although these data were based on a large consecutive series of gastric ESDs. Second, the present study was conducted at a single major referral cancer center in a large metropolitan area of Japan with many highly experienced endoscopists with specific expertise in ESD. Thus, a prospective multicenter study is required for a more precise evaluation of the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation induced by gastric ESD. Several multicenter prospective cohort studies on gastric ESD are currently underway[29-31].

In conclusion, endoscopists must be aware of not only the identified factors associated with delayed perforation induced by gastric ESD, but also how to treat this complication effectively and promptly.

We thank Dr. Hiroyuki Ono and Dr. Takuji Gotoda (our mentors of National Cancer Center Hospital in Tokyo) for their efforts in developing ESD.

Delayed perforation after gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) is a rare but serious complication that sometimes requires emergent surgery. Therefore, the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation after gastric ESD should be clarified to minimize its incidence and to treat this complication effectively and promptly.

Although several reports have described delayed perforation after gastric ESD, no published report has thoroughly evaluated the various factors associated with delayed perforation in addition to the actual clinical management of this complication based on data from a large series of consecutive patients undergoing gastric ESD.

The early recognition of the onset of delayed perforation after the sudden appearance of symptoms of peritoneal or mediastinal pleura irritation (gastric tube cases) within 24 h after gastric ESD followed by prompt conservative treatment may be useful for avoiding emergency surgery. In addition, in cases of ESD for gastric tube cancer, it might be better to avoid excessive electrical cautery during submucosal dissection or repeated coagulation so as to prevent delayed perforation.

The results of the present study suggest that endoscopists should be aware of not only the identified factors associated with delayed perforation, but also how to treat this complication effectively and promptly.

Bleeding and perforation are major complications of gastric ESD. ESD-related perforations can be subdivided into perforations that occur during gastric ESD and delayed perforations occurring after the completion of gastric ESD. Most perforations occur during gastric ESD, and the majority of perforation cases can be treated conservatively using complete endoscopic closure with endoclips. In contrast, delayed perforation is a rare but serious complication that sometimes requires emergent surgery.

This study is significant because it clarified both the actual clinical management and the associated factors of delayed perforation based on data from a large consecutive series of patients undergoing gastric ESD.

P- Reviewer: Chung JW, Gonzalez N, Kim GH, Man-I M, Matsumoto S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, Kato Y. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219-225. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, Fujisaki J, Sano T, Yamaguchi T. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 368] [Article Influence: 24.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese gastric cancer treatment guidelines 2010 (ver. 3). Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:113-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1723] [Cited by in RCA: 1897] [Article Influence: 135.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chung JW, Jung HY, Choi KD, Song HJ, Lee GH, Jang SJ, Park YS, Yook JH, Oh ST, Kim BS. Extended indication of endoscopic resection for mucosal early gastric cancer: analysis of a single center experience. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:884-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim YJ, Park DK. Management of complications following endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;3:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oda I, Suzuki H, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S. Complications of gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 1:71-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 161] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Miyahara K, Iwakiri R, Shimoda R, Sakata Y, Fujise T, Shiraishi R, Yamaguchi K, Watanabe A, Yamaguchi D, Higuchi T. Perforation and postoperative bleeding of endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric tumors: analysis of 1190 lesions in low- and high-volume centers in Saga, Japan. Digestion. 2012;86:273-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Toyokawa T, Inaba T, Omote S, Okamoto A, Miyasaka R, Watanabe K, Izumikawa K, Horii J, Fujita I, Ishikawa S. Risk factors for perforation and delayed bleeding associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric neoplasms: analysis of 1123 lesions. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ohta T, Ishihara R, Uedo N, Takeuchi Y, Nagai K, Matsui F, Kawada N, Yamashina T, Kanzaki H, Hanafusa M. Factors predicting perforation during endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1159-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yoo JH, Shin SJ, Lee KM, Choi JM, Wi JO, Kim DH, Lim SG, Hwang JC, Cheong JY, Yoo BM. Risk factors for perforations associated with endoscopic submucosal dissection in gastric lesions: emphasis on perforation type. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2456-2464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kim M, Jeon SW, Cho KB, Park KS, Kim ES, Park CK, Seo HE, Chung YJ, Kwon JG, Jung JT. Predictive risk factors of perforation in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a large, multicenter study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1372-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Watari J, Tomita T, Toyoshima F, Sakurai J, Kondo T, Asano H, Yamasaki T, Okugawa T, Ikehara H, Oshima T. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for perforation in gastric endoscopic submucosal dissection: A prospective pilot study. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;5:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Minami S, Gotoda T, Ono H, Oda I, Hamanaka H. Complete endoscopic closure of gastric perforation induced by endoscopic resection of early gastric cancer using endoclips can prevent surgery (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:596-601. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Hanaoka N, Uedo N, Ishihara R, Higashino K, Takeuchi Y, Inoue T, Chatani R, Hanafusa M, Tsujii Y, Kanzaki H. Clinical features and outcomes of delayed perforation after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2010;42:1112-1115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ikezawa K, Michida T, Iwahashi K, Maeda K, Naito M, Ito T, Katayama K. Delayed perforation occurring after endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kato M, Nishida T, Tsutsui S, Komori M, Michida T, Yamamoto K, Kawai N, Kitamura S, Zushi S, Nishihara A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection as a treatment for gastric noninvasive neoplasia: a multicenter study by Osaka University ESD Study Group. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:325-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Onozato Y, Iizuka H, Sagawa T, Yoshimura S, Sakamoto I, Arai H, Ishihara H, Tomizawa N, Ogawa T, Takayama H. A case report of delayed perforation due to endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early gastric cancer. Prog Digest Endosc. 2006;68:114-115. |

| 18. | Hirasawa T, Yamamoto Y, Okada K, Hayashi Y, Nego M, Kishihara T, Yoshimoto K, Ishiyama A, Ueki N, Ogawa T. A case of the delayed perforation due to endoscopic submucosal dissection for the early gastric cancer of the residual stomach. Prog Digest Endosc. 2009;74:52-53. |

| 19. | Kang SH, Lee K, Lee HW, Park GE, Hong YS, Min BH. Delayed Perforation Occurring after Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer. Clin Endosc. 2015;48:251-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ono H, Takizawa K, Kakushima N, Tanaka M, Kawata N. Application of polyglycolic acid sheets for delayed perforation after endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Endoscopy. 2015;47 Suppl 1 UCTN:E18-E19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sekiguchi M, Suzuki H, Oda I, Abe S, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Taniguchi H, Sekine S, Kushima R, Saito Y. Favorable long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for locally recurrent early gastric cancer after endoscopic resection. Endoscopy. 2013;45:708-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Suzuki H, Oda I, Nonaka S, Yoshinaga S, Saito Y. Is endoscopic submucosal dissection an effective treatment for operable patients with clinical submucosal invasive early gastric cancer? Endoscopy. 2013;45:93-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Nonaka S, Oda I, Sato C, Abe S, Suzuki H, Yoshinaga S, Hokamura N, Igaki H, Tachimori Y, Taniguchi H. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for gastric tube cancer after esophagectomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:260-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Mukasa M, Takedatsu H, Matsuo K, Sumie H, Yoshida H, Hinosaka A, Watanabe Y, Tsuruta O, Torimura T. Clinical characteristics and management of gastric tube cancer with endoscopic submucosal dissection. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:919-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma: 3rd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:101-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2390] [Cited by in RCA: 2872] [Article Influence: 205.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Matsuda T, Fujii T, Emura F, Kozu T, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Saito D. Complete closure of a large defect after EMR of a lateral spreading colorectal tumor when using a two-channel colonoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:836-838. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nonaka S, Saito Y, Takisawa H, Kim Y, Kikuchi T, Oda I. Safety of carbon dioxide insufflation for upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopic treatment of patients under deep sedation. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1638-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Onogi F, Araki H, Ibuka T, Manabe Y, Yamazaki K, Nishiwaki S, Moriwaki H. “Transmural air leak”: a computed tomographic finding following endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric tumors. Endoscopy. 2010;42:441-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Oda I, Shimazu T, Ono H, Tanabe S, Iishi H, Kondo H, Ninomiya M. Design of Japanese multicenter prospective cohort study of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer using Web registry (J-WEB/EGC). Gastric Cancer. 2012;15:451-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kurokawa Y, Hasuike N, Ono H, Boku N, Fukuda H. A phase II trial of endoscopic submucosal dissection for mucosal gastric cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0607. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39:464-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Takizawa K, Takashima A, Kimura A, Mizusawa J, Hasuike N, Ono H, Terashima M, Muto M, Boku N, Sasako M. A phase II clinical trial of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer of undifferentiated type: Japan Clinical Oncology Group study JCOG1009/1010. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2013;43:87-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |