Published online Nov 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12612

Peer-review started: March 17, 2015

First decision: May 18, 2015

Revised: May 26, 2015

Accepted: August 29, 2015

Article in press: August 31, 2015

Published online: November 28, 2015

Processing time: 256 Days and 3.3 Hours

AIM: To compare the mid-term outcomes of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) in obese Korean patients.

METHODS: All consecutive patients who underwent either LSG or LRYGB with primary to treat morbid obesity between January 2011 and December 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 with inadequately controlled obesity-related comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, or obesity-related arthropathy) or BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were considered for bariatric surgery according to the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity-Asia Pacific Chapter Consensus statements in 2011. The decision regarding the procedure type was made on an individual basis following extensive discussion with the patient about the specific risks associated with each procedure. All operative procedures were performed laparoscopically by a single surgeon experienced in upper gastrointestinal surgeries. Baseline demographics, perioperative surgical outcomes, and postoperative anthropometric data from a prospectively established database were thoroughly reviewed and compared between the two surgical approaches.

RESULTS: One hundred four patients underwent LSG, and 236 underwent LRYGB. Preoperative BMI in the LSG group was significantly higher than that of the LRYGB group (38.6 kg/m2vs 37.2 kg/m2, P = 0.024). Patients with diabetes were more prevalent in the LRYGB group (18.3% vs 35.6%, P = 0.001). Operating time and hospital stay were significantly shorter in the LSG group compared with the LRYGB group (100 min vs 130 min, P < 0.001; 1 d vs 2 d, P = 0.003), but the incidence of perioperative complications was similar between the groups (P = 0.351). The mean percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) was 71.2% for LRYGB, while it was 63.5% for LSG, at mean follow-up periods of 18.0 and 21.0 mo, respectively (P = 0.073). The %EWL at 1, 3, 6, 12, 18, 24, and 36 mo was equivalent between the groups. Four patients required surgical revision after LSG (4.8%), while revision was only required in one case following LRYGB (0.4%; P = 0.011).

CONCLUSION: Both LSG and LRYGB are effective procedures that induce comparable weight loss in the mid-term and similar surgical risks, except for the higher revision rate after LSG.

Core tip: Both laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB) are effective procedures that result in comparable weight loss in the mid-term with similar surgical risks in obese Korean patients. However, a larger number of patients required revisional surgery following LSG than LRYGB. The long-term complications encountered after each procedure differed significantly, and these complications were not negligible. Surgeons should provide a tailored surgical option for each patient that takes into consideration the possible risks, as the long-term complications may have a significant influence on the quality of life following the surgery.

-

Citation: Park JY, Kim YJ. Laparoscopic gastric bypass

vs sleeve gastrectomy in obese Korean patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(44): 12612-12619 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i44/12612.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i44.12612

Obesity is one of the most concerning health problems in the world today, imposing a considerable financial burden on society[1]. Consistent effort has been made to enable individuals to achieve weight loss and, concomitantly, to manage a variety of obesity-related comorbidities. However, none of the currently available conservative measures has succeeded in realizing these goals, and at the present time, bariatric surgery has proven to be the most effective method for achieving sustained weight loss[2].

Among the various available options for bariatric surgery, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass has been considered the gold standard for several decades. This procedure has a relatively long history compared to the other available procedures, qualified with sufficient data involving satisfactory long-term outcomes in terms of durable weight loss and resolution of comorbidities[3]. Recently, however, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has been rapidly gaining popularity as a stand-alone treatment for morbid obesity[4]. It is thought to be technically less demanding and to offer a potential benefit of reduced risk of long-term complications compared to laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). The trend of exponential increase in LSG is even noticeable in Asian countries where bariatric surgery has only recently been introduced[4], although results regarding the long-term efficacy of LSG are still lacking.

The present study aimed to evaluate the mid-term efficacy of LSG and LRYGB and to compare the results between the two procedures in obese Korean patients at a single center.

All patients who were operated on at Soonchunhyang University Seoul Hospital, a tertiary referral medical center, between January 2011 and December 2012 were retrospectively reviewed. Of those, the patients who underwent either LRYGB or LSG with primary intent to treat morbid obesity were enrolled in the present study. Baseline, operative, and follow-up data from a prospectively established database were thoroughly reviewed and summarized. Approval for this review of hospital records was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (SCHUH 2014-12-006); the need for patient informed consent was waived.

Bariatric surgery candidates were selected according to the International Federation for the Surgery of Obesity-Asia Pacific Chapter Consensus statements in 2011[5]. As such, patients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg/m2 with inadequately controlled obesity-related comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, or obesity-related arthropathy) or with a BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2 were considered for bariatric surgery. The decision regarding the procedure type was made on an individual basis following extensive discussion with the patient about the specific risks associated with each procedure. Patients received interdisciplinary education about potential surgical and nonsurgical options, possible outcomes, possible complications, and necessary postoperative lifestyle changes and nutritional supplementation.

All operative procedures were performed laparoscopically by a single surgeon experienced in upper gastrointestinal surgeries. Six trocars were used both in LSG and LRYGB; one 11-mm port for a scope at the umbilicus, two 12-mm ports, and three additional 5-mm ports. A 34 Fr bougie dilator was used for guidance during gastric resection in LSG. The lengths of the alimentary and biliopancreatic limbs were estimated at about 70-100 cm and 50 cm, respectively, and a 15-20 mm sized linear stapled gastrojejunostomy was established in LRYGB. Detailed surgical procedures were well described in our previously published study[6].

Patients returned to the outpatient clinic 2 wk after surgery and then every 3 mo for the first postoperative year to monitor weight loss, dysphagia or food intolerance, eating behavior, comorbidity status, and the presence of any complications. Follow-up frequency was then increased to every 12 mo after the first year. Telephone interviews were also used to monitor patients who were unable to visit the outpatient clinic.

The degree of weight loss was expressed as the percentage of total weight loss (%TWL) and the percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL), with the calculation of ideal body weight as that equivalent to a BMI of 23 kg/m2 according to the World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended definition of obesity for Asians[7].

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Medians with interquartile ranges of the variables were calculated and compared between the two different procedures. The χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was applied to analyze categorical variables, while Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables. All tests were two-tailed and P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

A total of 340 consecutive patients underwent either LSG or LRYGB for morbid obesity during the study period and were included in the study. One hundred four patients (30.6%) underwent LSG, while 236 patients (69.4%) underwent LRYGB. The demographic characteristics are shown in detail in Table 1. In the LSG group, the patients were younger, and the proportion of males was greater (P < 0.001 for both factors) than the LRYGB group. Preoperative BMI was 38.6 kg/m2 [interquartile rage (IQR), 34.8-43.8] in the LSG group, which was significantly higher than the BMI of 37.2 kg/m2 (IQR, 33.6-41.7) for the LRYGB group (P = 0.024). Patients with diabetes were more prevalent in the LRYGB group (35.6% vs 18.3%, P = 0.001), while the incidence of other obesity-related comorbidities was similar between the two groups.

| LSG (n = 104) | LRYGB (n = 236) | P value1 | |

| Age (yr) | 31 (25-38) | 38 (29-46) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 41 (39.4) | 37 (15.7) | < 0.001 |

| Female | 63 (60.6) | 199 (84.3) | |

| Body weight (kg) | 107.0 (95.0-130.8) | 100.0 (87.0-116.8) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 38.6 (34.8-43.8) | 37.2 (33.6-41.7) | 0.024 |

| Excess weight (kg)2 | 43.1 (33.5-62.6) | 38.4 (28.1-52.6) | 0.003 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Diabetes | 19 (18.3) | 84 (35.6) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 28 (26.9) | 88 (37.3) | 0.082 |

| Dyslipidemia | 64 (67.4) | 116 (68.2) | 0.892 |

| OSA | |||

| Confirmed | 10 (10.5) | 24 (14.1) | 0.514 |

| Suspicious | 4 (4.2) | 11 (6.5) | |

| Arthropathy | 12 (12.6) | 31 (18.2) | 0.298 |

| GERD | 14 (13.5) | 19 (8.1) | 0.163 |

| PCOS3 | 12 (19.0) | 30 (15.1) | 0.554 |

| No. of comorbidities | 1.5 (1-2) | 2 (1-3) | 0.031 |

The mean operating time and the length of hospital stay were significantly shorter in the LSG group than in the LRYGB group (100 min vs 130 min, P < 0.001; 1 d vs 2 d, P = 0.003; Table 2). There was one patient in whom the scheduled LRYGB was converted to LSG because of severe adhesions between small bowel loops associated with a previous history of panperitonitis. The left gastroepiploic vessels were injured during LSG in one patient, but there was no further evidence of ischemia. Technical failure of gastrojejunostomy reconstruction was encountered for four patients in the LRYGB group; successful laparoscopic revision was accomplished for all during the surgery. The incidence and severity of postoperative complications did not statistically differ between the groups (P = 0.351). Most complications in the LSG group were minor, involving operative wound or dietary problems; two severe complications were related to intra-abdominal bleeding in the immediate postoperative period that required reoperation to achieve hemostasis. Meanwhile, more than half of the complications (18/34, 52.9%) were associated with postoperative bleeding in the LRYGB group; 12 of these were mild, four were moderate, and two were severe complications. The overall incidence of postoperative bleeding was 7.6%, where two-thirds of the cases presented as luminal bleeding and one-third presented as intra-abdominal bleeding. Clinically significant hemorrhage requiring transfusion or invasive intervention occurred in 10 patients (4.2%) undergoing LRYGB. Other severe complications included one case of gastric pouch leakage and one intestinal obstruction; both of these required surgical intervention.

| LSG (n = 104) | LRYGB (n = 236) | P value1 | |

| Combined operation | 5 (4.8) | 19 (8.1) | 0.282 |

| Operating time (min) | 100 (90-115) | 130 (110-150) | < 0.001 |

| Intraoperative blood loss | 100 (50-150) | 100 (50-200) | 0.010 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 1 (1-2) | 2 (1-2) | 0.003 |

| Intraoperative complication | 1 (1.0) | 4 (1.7) | > 0.999 |

| Postoperative complication2 | |||

| No | 95 (91.3) | 202 (85.6) | 0.351 |

| Yes | |||

| Mild | 7 (6.7) | 25 (10.6) | |

| Moderate | 0 (0) | 5 (2.1) | |

| Severe | 2 (1.9) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Re-admission | 3 (2.9) | 8 (3.4) | > 0.999 |

Patients were followed up for an average of approximately 21.0 mo and 18.0 mo in the LSG and LRYGB groups, respectively (Table 3). Although the postoperative BMI was significantly higher in the LSG group than in the LRYGB group (28.5 kg/m2vs 27.3 kg/m2, P = 0.014) at the last follow-up, the %EWL and %TWL were similar between the groups (63.5% vs 71.2%, P = 0.073; 25.0% vs 26.7%, P = 0.394). The proportion of patients who had failed to achieve 50% of EWL 1 year postoperatively was larger in the LSG group (21.2%) than in the LRYGB group (13.6%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.148). Five patients in the LSG group (4.8%) required revisional surgery following the initial procedure because of intolerable de novo reflux disease (n = 2) and insufficient weight loss (n = 3). On the other hand, only one patient (0.4%) who had undergone LRYGB requested revision, RYGB reversal, due to malnutrition, and the rate of revision was significantly lower than in the LSG group (P = 0.011).

| LSG (n = 104) | LRYGB (n = 236) | P value1 | |

| Mean follow-up period (mo) | 21.0 (14.5-28.0) | 18.0 (12.0-24.0) | 0.012 |

| At last follow up | |||

| Body weight (kg) | 81.5 (64.0-98.5) | 72.0 (63.0-85.0) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 28.5 (24.5-34.2) | 27.3 (24.1-30.2) | 0.014 |

| %EWL (%)2 | 63.5 (44.8-88.0) | 71.2 (53.7-91.1) | 0.073 |

| %TWL (%) | 25.0 (19.4-32.9) | 26.7 (20.0-32.4) | 0.394 |

| EWL < 50% at 1 year | 18 (21.2) | 23 (13.6) | 0.148 |

| Revision | 5 (4.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0.011 |

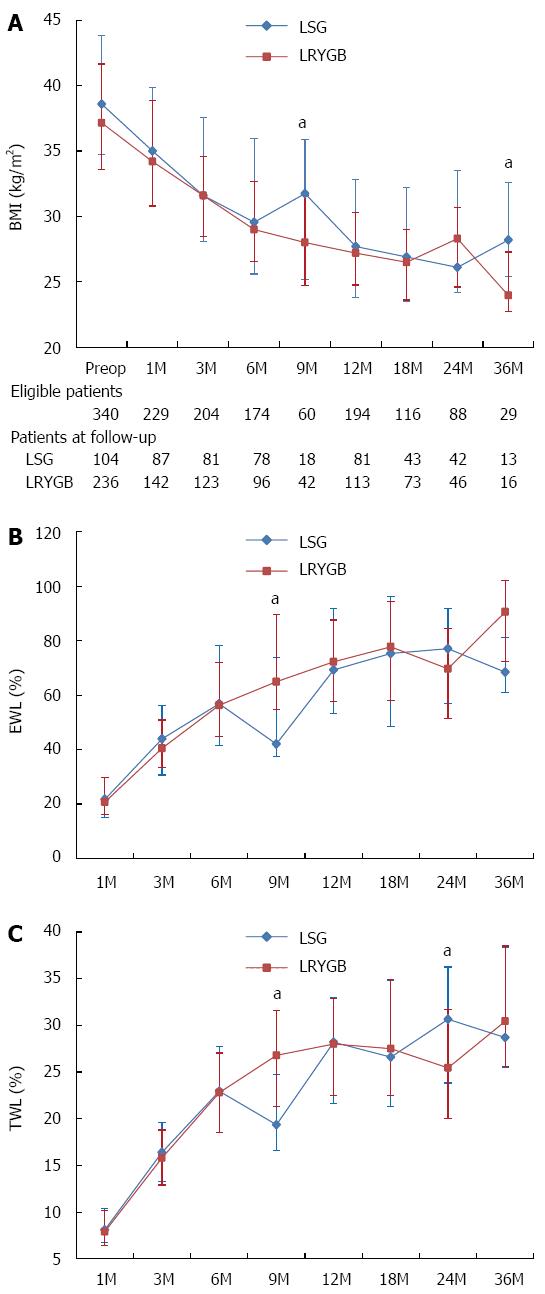

The chronological changes in anthropometric data during the follow-up period are shown in Figure 1. The body weight and BMI of the LSG group were generally higher than those of the LRYGB group throughout the study period. However, there were no significant differences between the LSG and LRYGB groups in %EWL and %TWL, which plateaued at around 80% and 30%, respectively, in both groups.

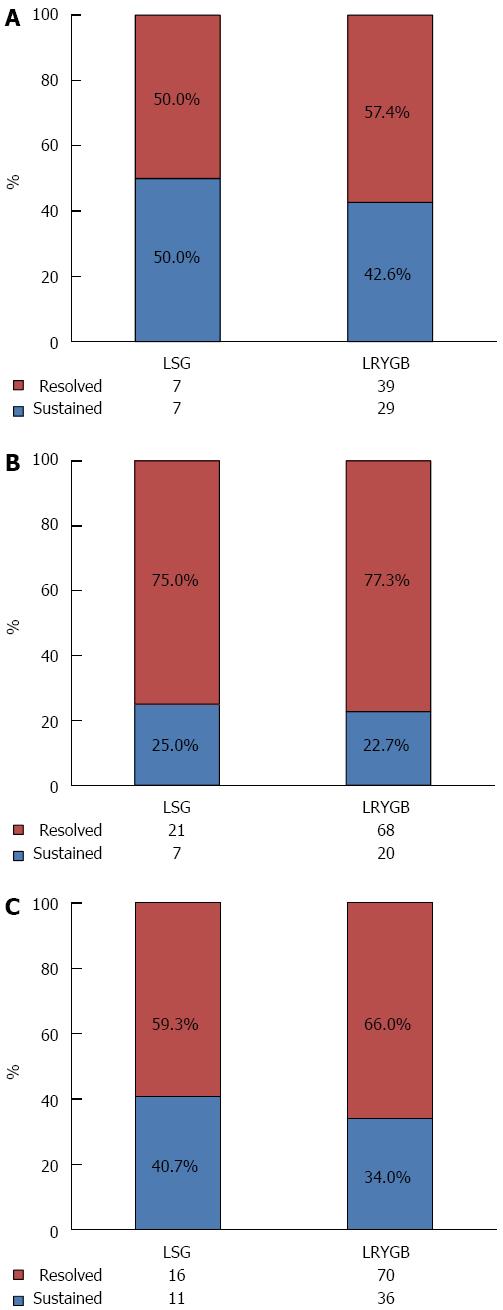

The obesity-related comorbidities were resolved in a considerable number of patients in both groups. The overall resolution rates of the obesity-related comorbidities were 56.1% for type 2 diabetes, 76.7% for hypertension, and 64.7% for dyslipidemia in the entire study population. No difference was observed between the LSG and LRYGB groups regarding comorbidity resolution (Figure 2).

Differences were observed between the groups in the types of long-term complications experienced (Table 4). Twenty-eight patients (26.9%) presented with gastroesophageal reflux symptoms following LSG; 24 of these suffered from de novo reflux symptoms after the surgery, and four showed aggravation of pre-existing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). The most frequently encountered long-term complication following LRYGB was marginal ulcers. The clinical symptom-based incidence reached 27.1%, but only one-fourth of the cases were confirmed with endoscopic evaluation. Most of the symptoms associated with both reflux esophagitis and marginal ulcers were well managed with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). However, two patients in the LSG group were converted to LRYGB due to intolerable reflux symptoms, and one patient in the LRYGB group developed panperitonitis owing to marginal ulcer perforation and required emergent laparotomic exploration to redo the gastrojejunostomy.

| LSG (n = 104) | LRYGB (n = 236) | ||

| GERD | 28 (26.9) | Marginal ulcer | 64 (27.1) |

| Anemia | 4 (3.8) | Confirmed by endoscopy | 15 (6.4) |

| Clinically suspicious | 49 (20.8) | ||

| Anemia | 53 (22.5) | ||

| GERD | 11 (4.7) | ||

| Peterson hernia | 3 (1.3) | ||

| Ventral hernia | 3 (1.3) | ||

In the present study, both LSG and LRYGB were found to be effective bariatric procedures with similar surgical risks leading to equivalent weight loss outcomes and comorbidity resolution during the medium-term follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report comparing LSG vs LRYGB in obese Korean patients, and we believe that this study will provide valuable information to better guide clinical decisions for individual obese patients in Korea.

Bariatric surgery is relatively new in East Asian countries, including Korea. There is a marked tendency in the region to prefer technically less demanding procedures, including laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding or LSG, over more complicated procedures such as LRYGB or biliopancreatic diversion[4]. This might be attributable to the surgeons’ lack of experience as well as to the sufficient weight loss outcomes achieved by these relatively simple restrictive procedures. The surgeon in the current study first began to perform the technically less demanding LSG in 2008, and then, starting in 2011, gradually began to adopt the more complicated LRYGB, after experience with 100 cases of LSG. In the present study, we enrolled patients who underwent surgery when the two surgical options were evenly offered to prospective candidates. The selection of the procedure type largely depended on the patient’s decision after thorough discussion regarding the outcomes and potential risks of each procedure based on the historical data. However, LSG was prioritized in super obese patients with BMI over 50 kg/m2 to reduce surgical risks with further staged operation in mind. This tendency has been reflected in the higher preoperative BMI of the LSG group compared to that of the LRYGB group.

LSG has been advocated for its technical simplicity and reduced surgical risks compared to LRYGB[8,9]. According to a recent meta-analysis by Zhang et al[10], LSG was shown to have statistically fewer major complications than LRYGB. The perioperative surgical outcomes in our series also suggested that LSG was technically less demanding than LRYGB, with a shorter operating time and hospital stay. Although the incidence of overall and severe complications did not statistically differ between LSG and LRYGB, the incidence of both did trend higher for LRYGB, and clinically significant bleeding requiring transfusion or reoperation developed more frequently following LRYGB. Given the disparity in surgical experience with LSG and LRYGB in our series, however, there is a chance that the complication rate of LRYGB can be further lowered with sufficient experience on the part of surgeons, and the trend toward higher complications may presumably recede.

In the present study, both procedures achieved a maximal %EWL of approximately 80% at between 12 and 18 mo postoperatively; this subsequently leveled off. These results are in line with the recently published literature reporting that the %EWL following LSG and LRGYB ranged from 60.0%-76.5% and 69.0%-76.6%, respectively, 1 year postoperatively, figures that were maintained as 60.0%-75.4% and 70.0%-73.0%, respectively, 2 years postoperatively[8,9,11,12]. The slightly higher %EWL in our study might be explained by the lower preoperative BMI of our study cohort, since %EWL is significantly influenced by initial BMI level[13]. The recent meta-analysis by Zhang et al found that the excess weight loss was similar between LSG and LRYGB in the early postoperative period, for up to 2 years[10]. The present study also revealed that LSG and LRYGB demonstrated almost equal efficacy in terms of %EWL during the study’s 3 years of postoperative follow-up. Some studies with longer follow-up periods have suggested that weight regain is more prevalent in patients who have undergone LSG[11,14], but the number of patients who were followed up in the present study became too small after 2 years to allow a definite conclusion. Longer follow-up with a larger number of patients is necessary to determine whether the reduced weight would be maintained thereafter. Interestingly, the attrition rate was higher in the LRYGB group than in the LSG group throughout the follow-up period, with the exception of the third year. This finding might be attributable to the fact that the surgeon traced the patients undergoing LSG more rigorously in order to evaluate whether or not they required secondary operations.

A recent meta-analysis suggested that LSG and LRYGB showed equivalent efficacy in regard to resolution of most of the obesity-related comorbidities, except for diabetic control where LRYGB was superior to LSG[10]. The current study showed similar resolution rates of hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes following both procedures. As shown by the preoperative clinical characteristics, the patients with diabetes in our study initially inclined toward LRYGB, expecting an additional metabolic effect from bypass. Therefore, there could be a selection bias from the beginning. In addition, the number of patients with diabetes in the LSG group was too small to allow a comprehensive comparison of the efficacy of the two procedures in diabetic control. Nonetheless, the resolution rate of diabetes in the current study was estimated to be less than 60% even following LRYGB, a figure which is much lower than the diabetes remission rate of 92%-95% reported in a recently published meta-analysis[15]. Ethnic differences in the characteristics of type 2 diabetes, such as early β-cell dysfunction, could be the reason for the decrease in effective diabetic control, despite equivalent %EWL, relative to the Western population-based studies[16].

The potential long-term complications can be an important issue when determining the type of surgical procedure for a given obese patient. The present study showed that patients undergoing LSG and LRGYB encountered different kinds of long-term complications following the surgery. LSG led to far less frequent nutritional problems, such as anemia, than LRYGB; but new onset GERD developed in about 23% of the patients. Although the majority of patients with pre-existing GERD (71.4% in the LSG group vs 94.7% in the LRYGB group) experienced symptom improvement along with weight loss following both procedures, the resolution rate was considerably lower in the LSG group, and some patients experienced endoscopically proven disease aggravation following LSG, similar to the results from a previous randomized trial[8]. On the other hand, marginal ulcer was one of the representative complications following LRYGB. The reported incidence varies significantly in the literature, ranging from 3.5% to 12.3%, depending on the definition and evaluation method[17-20]. The incidence of endoscopically confirmed marginal ulcers was 6.4% in the present study, which is consistent with previous reports. However, the actual incidence is expected to be higher, considering that only about half of the symptomatic patients were evaluated with endoscopy while the rest were managed with PPIs based on their symptoms. The incidence of marginal ulcer is reported to be as high as 27%-36% among symptomatic patients[21,22]. Currently, plausible risk factors for marginal ulcer following LRGYB include technical factors, such as a long gastric pouch or non-absorbable suture materials, smoking, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diabetes mellitus, and possibly Helicobacter pylori infection[19]. Although both post-LSG GERD and post-LRYGB marginal ulcers responded well to the PPI treatment, two LSG patients eventually required revisional surgery, and one LRYGB patient underwent emergent operation due to marginal ulcer perforation in our series. It is difficult to say which complications would be easier to manage. Nonetheless, surgeons should provide a tailored surgical option for each patient that takes into consideration the possible risks, as the long-term complications may have a significant influence on the quality of life following the surgery. We believe that LRYGB would be a better choice for the patients with symptomatic GERD preoperatively, while LSG would be recommended for those with poor compliance or for substance abusers, including heavy smokers.

There are several limitations to the present study. Above all, this study is a retrospective study based on prospectively collected data, and there could be a selection bias for each group, as shown in the preoperative demographics. Well-designed randomized trials are necessary to truly elucidate the differences between LSG and LRYGB. The attrition rate in our series was also quite high, a finding that seems to be a universal challenge among other institutions. Since bariatric surgery and its related examinations are not reimbursed at all in South Korea, the costs for the follow-up examinations must come directly from the patients. Patients are reluctant to cover all of the expenses for regular surveillance unless they feel that something is wrong, a situation which renders our follow-up data less reliable.

In conclusion, both LSG and LRYGB are effective procedures that yield comparable weight loss in the mid-term with similar surgical risks. However, a larger number of patients required revisional surgery following LSG. The long-term complications encountered after each procedure differ significantly, and these complications are not negligible. Longer follow-up periods are necessary to compare the long-term differences in weight loss and complications between LSG and LRYGB.

Min Ju Soh cordially supported this study as a research coordinator.

Bariatric surgery is relatively new in East Asian countries, including South Korea. There is a marked tendency in the region to prefer technically less demanding and purely restrictive procedures, including laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG), over more complicated procedures such as laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (LRYGB). Therefore, comparisons between LRYGB and LSG are still lacking from Asian countries to demonstrate of the efficacy of each procedure.

The present study evaluated the mid-term efficacy of LSG and LRYGB and compared the results between the two procedures in obese Korean patients at a single center.

Both LSG and LRYGB were found to be effective bariatric procedures with similar surgical risks leading to equivalent weight loss outcomes and comorbidity resolution during the mid-term follow-up. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report comparing LSG vs LRYGB in obese Korean patients.

This study will provide valuable information to guide clinical decisions for individual obese patients in Asian countries. LRYGB would be a better choice for the patients with symptomatic GERD preoperatively, while LSG would be recommended for those with poor compliance or for substance abusers, including heavy smokers.

The authors present a head-to-head comparison of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass procedure as performed at a single Korean center. They performed a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data. Overall the manuscript is well organized and very well written. The authors are to be commended for their work.

P- Reviewer: Guidry CA, Pai SI S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Finkelstein EA. How big of a problem is obesity? Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:569-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sjöström L. Review of the key results from the Swedish Obese Subjects (SOS) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1241] [Cited by in RCA: 1267] [Article Influence: 105.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Buchwald H, Avidor Y, Braunwald E, Jensen MD, Pories W, Fahrbach K, Schoelles K. Bariatric surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2004;292:1724-1737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5073] [Cited by in RCA: 4713] [Article Influence: 224.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Buchwald H, Oien DM. Metabolic/bariatric surgery worldwide 2011. Obes Surg. 2013;23:427-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1020] [Cited by in RCA: 1004] [Article Influence: 83.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kasama K, Mui W, Lee WJ, Lakdawala M, Naitoh T, Seki Y, Sasaki A, Wakabayashi G, Sasaki I, Kawamura I. IFSO-APC consensus statements 2011. Obes Surg. 2012;22:677-684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park JY, Song D, Kim YJ. Clinical experience of weight loss surgery in morbidly obese Korean adolescents. Yonsei Med J. 2014;55:1366-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | The Asia-Pacific Perspective: redefining obesity and its treatment. Health Communications, Sydney. Sidney: World Health Organization; . |

| 8. | Peterli R, Borbély Y, Kern B, Gass M, Peters T, Thurnheer M, Schultes B, Laederach K, Bueter M, Schiesser M. Early results of the Swiss Multicentre Bypass or Sleeve Study (SM-BOSS): a prospective randomized trial comparing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2013;258:690-694; discussion 695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 261] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carlin AM, Zeni TM, English WJ, Hawasli AA, Genaw JA, Krause KR, Schram JL, Kole KL, Finks JF, Birkmeyer JD. The comparative effectiveness of sleeve gastrectomy, gastric bypass, and adjustable gastric banding procedures for the treatment of morbid obesity. Ann Surg. 2013;257:791-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang C, Yuan Y, Qiu C, Zhang W. A meta-analysis of 2-year effect after surgery: laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity and diabetes mellitus. Obes Surg. 2014;24:1528-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vidal P, Ramón JM, Goday A, Benaiges D, Trillo L, Parri A, González S, Pera M, Grande L. Laparoscopic gastric bypass versus laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy as a definitive surgical procedure for morbid obesity. Mid-term results. Obes Surg. 2013;23:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dogan K, Gadiot RP, Aarts EO, Betzel B, van Laarhoven CJ, Biter LU, Mannaerts GH, Aufenacker TJ, Janssen IM, Berends FJ. Effectiveness and Safety of Sleeve Gastrectomy, Gastric Bypass, and Adjustable Gastric Banding in Morbidly Obese Patients: a Multicenter, Retrospective, Matched Cohort Study. Obes Surg. 2015;25:1110-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | van de Laar A, de Caluwé L, Dillemans B. Relative outcome measures for bariatric surgery. Evidence against excess weight loss and excess body mass index loss from a series of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients. Obes Surg. 2011;21:763-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Himpens J, Dobbeleir J, Peeters G. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for obesity. Ann Surg. 2010;252:319-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 572] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 38.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang SH, Stoll CR, Song J, Varela JE, Eagon CJ, Colditz GA. The effectiveness and risks of bariatric surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis, 2003-2012. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:275-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1385] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Ma RC, Chan JC. Type 2 diabetes in East Asians: similarities and differences with populations in Europe and the United States. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2013;1281:64-91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 578] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 51.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dallal RM, Bailey LA. Ulcer disease after gastric bypass surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2006;2:455-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | El-Hayek K, Timratana P, Shimizu H, Chand B. Marginal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: what have we really learned? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2789-2796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Coblijn UK, Goucham AB, Lagarde SM, Kuiken SD, van Wagensveld BA. Development of ulcer disease after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, incidence, risk factors, and patient presentation: a systematic review. Obes Surg. 2014;24:299-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rasmussen JJ, Fuller W, Ali MR. Marginal ulceration after laparoscopic gastric bypass: an analysis of predisposing factors in 260 patients. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1090-1094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Huang CS, Forse RA, Jacobson BC, Farraye FA. Endoscopic findings and their clinical correlations in patients with symptoms after gastric bypass surgery. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:859-866. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Wilson JA, Romagnuolo J, Byrne TK, Morgan K, Wilson FA. Predictors of endoscopic findings after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2194-2199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |