Published online Sep 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i35.10234

Peer-review started: April 10, 2015

First decision: May 18, 2015

Revised: June 2, 2015

Accepted: July 8, 2015

Article in press: July 8, 2015

Published online: September 21, 2015

Processing time: 161 Days and 2.6 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy (MBST) versus hybrid therapy as a first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

METHODS: From August 2014 to January 2015, 284 patients with confirmed H. pylori infection were randomized to receive a 14-d course of MBST (MBST group, n = 140) or hybrid (Hybrid group, n = 144) therapy. The MBST group received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 7 d, followed by 20 mg rabeprazole and 500 mg metronidazole twice daily, and 400 mg moxifloxacin once daily for 7 d. The Hybrid group received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 14 d. In addition, the Hybrid group received 500 mg metronidazole and 500 mg clarithromycin twice daily for the final 7 d. Successful eradication of H. pylori infection was defined as a negative 13C-urea breath test 4 wk after the end of treatment. Patient compliance was defined as “good” if drug intake was at least 85%. H. pylori eradication rates, patient compliance with treatment, and adverse event rates were evaluated.

RESULTS: The eradication rates in the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis were 91.4% (128/140; 95%CI: 90.2%-92.9%) in the MBST group and 79.2% (114/144; 95%CI: 77.3%-80.7%) in the Hybrid group (P = 0.013). The eradication rates in the per-protocol (PP) analysis were 94.1% (128/136; 95%CI: 92.9%-95.6%) in the MBST group and 82.6% (114/138; 95%CI: 80.6%-84.1%) in the Hybrid group (P = 0.003). The H. pylori eradication rate in the MBST group was significantly higher than that of the Hybrid group for both the ITT (P = 0.013) and the PP analyses (P = 0.003). Both groups exhibited full compliance with treatment (MBST/Hybrid group: 100%/100%). The rate of adverse events was 11.8% (16/136) and 19.6% (27/138) in the MBST and Hybrid group, respectively (P = 0.019). The majority of adverse events were mild-to-moderate in intensity; none were severe enough to cause discontinuation of treatment in either group.

CONCLUSION: MBST was more effective and led to fewer adverse events than hybrid therapy as a first-line treatment for H. pylori infection.

Core tip: To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of 14-d treatment with moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy compared with hybrid therapy as a first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. Our study shows that moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is more effective with fewer adverse events compared with hybrid therapy. The high rates of H. pylori eradication and patient compliance with treatment, and low rate of adverse events seen here suggest that moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is a suitable alternative to standard triple therapy.

-

Citation: Hwang JJ, Lee DH, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N. Efficacy of moxifloxacin-based sequential and hybrid therapy for first-line

Helicobacter pylori eradication. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(35): 10234-10241 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i35/10234.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i35.10234

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was first identified by Marshall and Warren in 1983[1]. H. pylori is a common pathogen that infects approximately half the global population and can cause chronic gastritis, peptic ulcers, gastric mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma[2]. Therapy to eradicate H. pylori can reduce the likelihood of peptic ulcer recurrence, induce remission of gastric mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and reduce the risk of early gastric cancer recurrence after endoscopic treatment. Hence, the need for therapies to eradicate H. pylori has become clear.

In 1997, the European Helicobacter Study Group recommended standard triple therapy using a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), amoxicillin, and clarithromycin as first-line therapy for H. pylori. This regimen is still widely used, including in the United States and Europe[3]. However, H. pylori eradication rates have been decreasing gradually with increasing resistance to clarithromycin due to its use in the treatment of respiratory infections over the past 20 years[4]. A report from Korea also indicates that rates of H. pylori eradication are decreasing[5]. Thus, the need for a new first-line therapy for H. pylori with a high eradication rate has become clear, and various alternatives to standard triple therapy are being investigated worldwide.

Sequential therapy was first described by Zullo et al[6] in 2000. It involves initial dual treatment with PPI and amoxicillin followed by triple treatment with PPI, clarithromycin, and metronidazole (or tinidazole). This treatment involves initial damage to the H. pylori cell wall from amoxicillin, allowing easier penetration of antibiotics such as clarithromycin. Cell wall damage also leads to the loss of channels to export clarithromycin; thus, antibiotics are retained and, even with resistance, treatment to eradicate bacteria is more effective[6]. Many studies and meta-analyses have reported high eradication rates with sequential therapy[7,8]; however, recent studies from Korea show that eradication rates are decreasing[9,10]. Accordingly, recent research has focused on the drug composition, duration, dosage, and the timing of drug administration in sequential therapy.

Hybrid therapy involves alterations to the sequential therapy regimen such that PPI and amoxicillin are administered initially as dual treatment followed by a quadruple regimen with PPI, amoxicillin, clarithromycin, and metronidazole (or tinidazole). Recent studies have reported higher eradication rates for hybrid therapy in comparison with sequential therapy without significant differences in treatment compliance or the incidence of adverse events[11,12]. However, comprehensive data on this subject are lacking. Moreover, very few studies have been based in Korea, where there is a high incidence of antibiotic resistance.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy, rates of patient compliance with treatment, and adverse events for two novel regimens for H. pylori infection treatment. A 14-d regimen of moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy (MBST) was compared with 14-d hybrid therapy to evaluate the most effective alternative first-line regimen for H. pylori eradication in the relatively antibiotic-resistant Korean population.

This prospective, open-label, randomized study was conducted at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between August 2014 and January 2015. A total of 284 patients infected with H. pylori were enrolled. H. pylori infection was defined by at least one of the following: a positive 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT); histologic evidence of H. pylori by modified Giemsa staining of tissue from the lesser and greater curvature of the stomach body and antrum; and/or a positive rapid urease test (CLO test; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) by gastric mucosal biopsy from the lesser curvature of the stomach body and antrum. Patients were excluded if they had received PPIs, H2 receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the previous 4 wk, or if they had used nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or steroids in the 2 wk prior to the 13C-UBT. Other exclusion criteria were as follows: patients were (1) below 18 years of age; (2) had undergone gastric surgery or endoscopic mucosal dissection for gastric cancer; (3) had advanced gastric cancer; (4) had severe current disease (hepatic, renal, respiratory, or cardiovascular); (5) were pregnant; or (6) had any condition that may have led to poor compliance with treatment (e.g., alcoholism or drug addiction). The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

This was a prospective, open-label, single-center, randomized study to compare 14-d MBST with 14-d hybrid therapy as first-line treatment for H. pylori infection. All enrolled patients completed a questionnaire regarding their history of comorbidities, demographic information, smoking status, and alcohol consumption. Patients also underwent an esophagogastroduodenoscopy to assess their clinical diagnosis, such as gastritis or peptic ulcer disease, and to conduct a biopsy for the assessment of H. pylori infection, colonization, atrophic change, and intestinal metaplasia. The 288 patients enrolled were randomly assigned to two treatment groups using a computer-generated numeric sequence. Four patients in the MBST group withdrew consent after the enrollment deadline. Thus, in the final analyses, the 14-d MBST group comprised 140 patients and the Hybrid group comprised 144 patients. The 14-d MBST group received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 7 d followed by 20 mg rabeprazole and 500 mg metronidazole twice daily, and 400 mg moxifloxacin once daily for 7 d. The Hybrid group received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for 14 d, plus 500 mg metronidazole and 500 mg clarithromycin twice daily for the final 7 d. Patient compliance with treatment was evaluated by remnant pill counting and direct questioning by a physician one week after completion of treatment. Compliance was defined as “good” with a drug intake of at least 85%. Patients were also questioned about adverse events at this time. Successful eradication of H. pylori infection was defined by a negative 13C-UBT test 4 wk after the end of treatment.

Before the 13C-UBT was conducted, patients were instructed to stop taking medications that could affect the result (e.g., bismuth, antibiotics for 4 wk, or PPIs for 2 wk), and fasted for a minimum of 4 h. The oral cavity was washed by gargling and 100 mg 13C-urea powder (UBiTkitTM; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) dissolved in 100 mL water was administered orally. Breath samples were taken with special breath collection bags before and 20 min after drug administration. Samples were analyzed using an isotope-selective, non-dispersive infrared spectrometer (UBiT-IR 300®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

The sample size was estimated based on recent domestic data on hybrid treatment efficacy[13]. To obtain a 12% difference in effectiveness between the two regimens, a power of 80% and a two-sided type 1 error of 5%, we calculated that a minimum of 135 patients were needed for each treatment arm; this would also allow for 10% loss to follow-up.

The primary outcome was H. pylori-eradication rate and the secondary outcome was safety as assessed by the rate of treatment-related adverse events. The eradication rate was determined by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. The ITT analysis included all patients originally allocated to the treatment arms and the PP analysis included patients who had completed treatment. The mean ± SD was calculated for quantitative variables. The student’s t test was used to evaluate continuous variables, and the χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were used to evaluate non-continuous variables. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW version 20.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). A P value less than 0.05 was considered to be clinically significant.

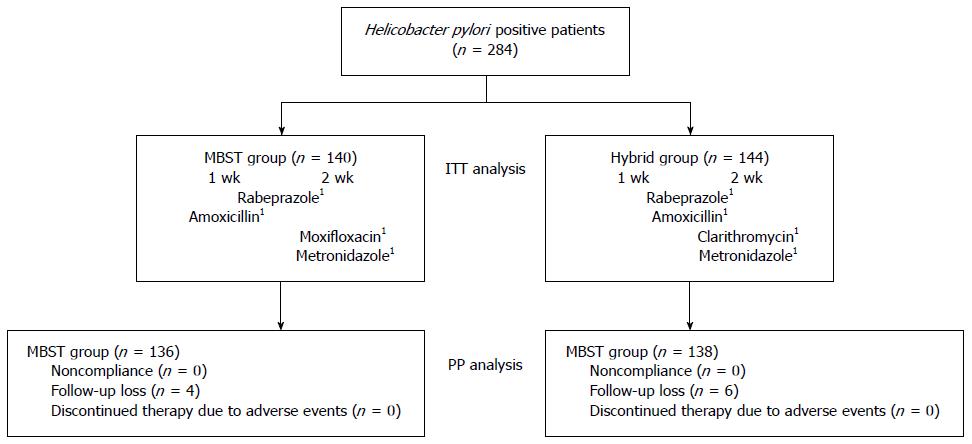

A schematic diagram of the study is provided in Figure 1. A total of 284 patients infected with H. pylori were randomized to the MBST group or Hybrid group. Of these, 274 (96.4%) completed their allocated regimens. The remaining 10 patients (3.5%) were excluded from the study due to follow-up loss, 4 (1.4%) from the MBST group and 6 (2.1%) from the Hybrid group. No patients were excluded from either group for non-compliance (< 85% of assigned tablets) and none discontinued treatment due to adverse events. Finally, 136 patients in the MBST group and 138 patients in the Hybrid group were included in the PP analysis. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics did not differ significantly between the two groups (Table 1).

| MBST | Hybrid | P value | |

| Included in ITT analysis | 140 | 144 | - |

| Age, mean ± SD (yr) | 58.9 ± 12.8 | 58.8 ± 11.9 | 0.922 |

| Gender (male) | 58 (41.4) | 72 (50.0) | 0.155 |

| Current smoker | 8 (5.7) | 9 (6.3) | 0.849 |

| Alcohol drinking | 18 (12.9) | 15 (10.4) | 0.581 |

| Diabetes | 7 (5.0) | 6 (4.2) | 0.783 |

| Hypertension | 27 (19.3) | 20 (13.9) | 0.264 |

| Previous history of peptic ulcer | 19 (13.6) | 18 (12.5) | 0.537 |

| Endoscopic diagnosis | 0.783 | ||

| HPAG | 117 (83.6) | 136 (94.4) | |

| Gastric ulcer | 8 (5.7) | 6 (4.2) | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 5 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Gastric and duodenal ulcer | 2 (1.4) | 2 (1.4) | |

| Adenoma | 8 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Positive CLO test | 106 (75.7) | 116 (80.6) | 0.389 |

| H. pylori colonization | 0.234 | ||

| Negative | 7 (5.0) | 13 (9.0) | |

| Mild | 66 (47.1) | 65 (45.1) | |

| Moderate | 52 (37.1) | 43 (29.9) | |

| Marked | 15 (10.7) | 23 (16.0) | |

| Atrophic change | 11 (7.8) | 14 (9.8) | 0.122 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 10 (7.2) | 16 (11.1) | 0.239 |

| Drop out | 4 (2.8) | 6 (4.1) | 0.285 |

| Noncompliance | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Follow-up loss | 4 (2.8) | 6 (4.1) | |

| Discontinued therapy | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| due to adverse events |

Table 2 shows the eradication rates for H. pylori according to the ITT and PP analyses. The overall ITT eradication rate was 85.2% (242/284), 91.4% (128/140; 95%CI: 90.2-92.9%) in the MBST group and 79.2% (114/144; 95%CI: 77.3-80.7%) in the Hybrid group (P = 0.013). The overall PP eradication rate was 88.3% (242/274); 94.1% (128/136; 95%CI: 92.9-95.6%) in the MBST group and 82.6% (114/138; 95%CI: 80.6-84.1%) in the Hybrid group (P = 0.003). The H. pylori eradication rates in the MBST group were significantly higher than those in the Hybrid group according to both the ITT (P = 0.013) and PP analysis (P = 0.003).

| MBST | Hybrid | P value | |

| ITT analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 91.4% (128/140) | 79.2% (114/144) | 0.013 |

| 95%CI | 90.2%-92.9% | 77.3%-80.7% | |

| PP analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 94.1% (128/136) | 82.6% (114/138) | 0.003 |

| 95%CI | 92.9%-95.6% | 80.6%-84.1% |

Sixteen out of 136 patients (11.8%) in the MBST group and 27 out of 138 patients (19.6%) in the Hybrid group experienced adverse events; the difference between groups was statistically significant (P = 0.019; Table 3). The most common adverse events were bloating/dyspepsia (4/136, 2.9%), taste distortion (4/136, 2.9%), and epigastric discomfort (4/136, 2.9%) in the MBST group and epigastric discomfort (7/138, 5.1%), and bloating/dyspepsia (5/138, 3.6%) in the Hybrid group. The majority of adverse events were mild-to-moderate in intensity and none were severe enough to cause discontinuation of treatment in either group. Treatment compliance was 100% for both groups (Table 3).

| MBST | Hybrid | P value | |

| Adverse events | (n = 136) | (n = 138) | |

| Bloating/dyspepsia | 4 (2.9) | 5 (3.6) | |

| Taste distortion | 4 (2.9) | 4 (2.9) | |

| Epigastric discomfort | 4 (2.9) | 7 (5.1) | |

| Nausea | 2 (1.5) | 4 (2.9) | |

| Abdominal pain | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Diarrhea | 2 (1.5) | 7 (5.1) | |

| Total | 16 (11.8) | 27 (19.6) | 0.019 |

| Compliance | 136 (100.0) | 138 (100.0) |

Eradication rate is an important standard in assessing the success of H. pylori treatment. The Maastricht Consensus Conference declared that eradication rates > 80% and > 90% in ITT and PP analyses, respectively, have therapeutic significance[14]. However, many countries have reported eradication rates < 80% for standard triple therapy[15,16]. Among the factors contributing to low eradication rates, antibiotic resistance poses the largest problem, particularly increasing clarithromycin resistance[4]. As the search for an effective H. pylori vaccine is exhausted, a number of studies have focused on increasing the duration of eradication therapy, altering drug compositions, increasing drug dosage, and combining existing and new antibiotics to overcome antibiotic resistance and increase eradication rates.

A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials conducted in Italy before 2008 showed an eradication rate of 91.0%-93.5% (ITT analysis) with sequential therapy, significantly higher than the 75.7%-79.2% eradication rate with standard triple therapy[7]. The majority of randomized controlled trials conducted in Europe after 2008 showed eradication rates for ITT analyses > 80% for sequential therapy, showing this regimen to be superior to standard triple therapy[17,18]. In a meta-analysis of 6 randomized prospective studies conducted in Korea, the eradication rates with sequential therapy in the ITT and PP analyses were 79.4% and 86.4%, respectively, with a relative risk of 1.761 in the ITT analysis[19]. However, despite superior eradication rates in comparison with standard triple therapy, rates for sequential therapy in Korea were not as high as expected (ITT, 79.4%; PP, 86.4%)[19] and failed to meet the threshold for therapeutic significance.

Recent studies have explored hybrid therapy, whereby the duration of treatment with components of sequential therapy is altered. Eradication rates of 97.4% and 99.1% in ITT and PP analyses, respectively, have been reported in Taiwan[11], and 89.5% and 92.9%, respectively, in Iran[12]. However, an Italian study reported rates of 80% and 85.7%[17] and a Korean study reported 81.1% and 85.9%, respectively, indicating regional differences[13].

Furthermore, some studies have attempted to substitute clarithromycin with other antibiotics due to its contribution to treatment failure with moxifloxacin, a second-generation fluoroquinolone mainly used to treat respiratory infections, receiving particular attention. Moxifloxacin is characterized by fast absorption with a bioavailability of 89% due to oral administration and broad penetration through body fluids and tissues[20]. It also has fewer adverse effects and interactions with other drugs compared with other fluoroquinolones[21]. In a pilot study by this group comparing clarithromycin- with MBST, significantly higher eradication rates (ITT, 91.3%; PP, 93.6%) were seen for MBST compared with clarithromycin-based sequential therapy (ITT, 71.6%; PP, 75.3%), with no significant differences in treatment compliance or adverse events[22].

Therefore, the present study aimed to determine the most effective first-line therapy for H. pylori in Korean patients by conducting a head-to-head comparison of eradication rates, treatment compliance, and adverse effects for 14-d MBST and a regimen in which clarithromycin was substituted for moxifloxacin. We hypothesized that changing the antibiotic agents that are included in the eradication regimen would be more effective than extending the treatment duration for existing antibiotics to improve H. pylori eradication therapy efficacy. Our results indicate that 14-d MBST achieves significantly higher eradication rates than 14-d hybrid therapy.

We believe these results may be related to antibiotic resistance. A previous study on antibiotic resistance conducted by our institution showed clarithromycin resistance rates of 23.2% from 2003 to 2005, 27.2% from 2006 to 2008, and 37.3% from 2009 to 2013[23]. Resistance rates to metronidazole decreased in 2003 to 2005 (34.8%) and 2006 to 2008 (23.8%), followed by an increase to 35.8% from 2009 to 2013[23]. Resistance to moxifloxacin has increased continually, from 5.8% in 2003 to 2005, to 23.3% in 2006 to 2008, and 37.3% in 2009 to 2013[23]. Although these antibiotics all showed resistance rates > 30%, the eradication rates of the two therapies tested here were significantly different. This difference may relate to clarithromycin and metronidazole double-resistance, the rate of which is 9.6% in Korea compared with 3.5%-4.3% in Italy[24,25]. According to a study by Wu et al[26], patients with double resistance to clarithromycin and imidazole show significantly lower eradication rates with sequential therapy. Another study reported that eradication rates for a particular regimen can be estimated using the resistance and eradication rates for each antibiotic[27]. Based on this calculation, the treatment failure rate increased in patients with double resistance to clarithromycin and metronidazole, with a double resistance rate > 5% leading to a decrease in eradication rate to < 90% in the PP analysis for 14-d sequential therapy[27]. In addition, many studies have reported that increased clarithromycin and imidazole double resistance reduces the efficacy of sequential therapy[28,29]. This may account for the lower eradication rate with hybrid therapy in the present study. However, as there is no data to date on double resistance to moxifloxacin and metronidazole, comparisons with different antibiotics are difficult. Hence, further studies on this topic are necessary.

The most common adverse effects associated with moxifloxacin are gastrointestinal disturbances such as nausea or diarrhea[21] with the most common in this study being epigastric discomfort and bloating/dyspepsia. The overall incidence of adverse events was 11.8% in the MBST group, significantly lower than the 19.6% in the Hybrid group. All adverse events were mild to moderate, and none resulted in discontinuation or disturbance to daily activities.

This study had some limitations. First, an antibiotic susceptibility test to assess antibiotic resistance was not performed. Such tests can be difficult to conduct in clinical settings due to cost and time constraints[30]. To overcome this we used data from a study on antibiotic resistance with H. pylori conducted at our institution[23]. Furthermore, to eliminate selection bias, patients were allocated randomly to ensure antibiotic resistance was distributed equally between groups. Second, this was a single-center study with a relatively small number of subjects. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials with more subjects are needed to verify the efficacy of the MBST regimen.

In conclusion, 14-d MBST is more effective and has fewer adverse effects than 14-d hybrid therapy as a first-line treatment for H. pylori. We believe that the high eradication rates, good treatment compliance, and low rate of adverse events associated with MBST make it a potential alternative to standard triple therapy. The efficacy of this therapy should be verified and its applicability for general use determined through a large-scale prospective study in comparison with established first-line therapies.

A recent meta-analysis reported that the efficacy of sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection in Asia is modest, highlighting the need for a more effective regimen.

The potential of the antibiotic moxifloxacin in the eradication of H. pylori infection has been suggested by a small number of studies in animals and humans.

This randomized controlled study evaluated the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy (compared with 14-d hybrid therapy) as a first-line treatment for H. pylori infection. The high rates of H. pylori eradication and patient compliance with treatment, and low rates of adverse events associated with 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy suggest it is a suitable alternative to standard triple therapy.

This study’s design and findings could be used to determine the sample size for a larger, multicenter study to verify the efficacy of novel therapies for H. pylori eradication.

H. pylori is found in the stomach and is associated with the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers, and stomach cancer. Eradication of H. pylori infection is essential to prevent recurrence in patients with these diseases.

This is a good prospective study comparing moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy with hybrid therapy. The result is obvious and significant.

P- Reviewer: Du YQ, Pellicano R, Siavoshi F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Marshall BJ, Warren JR. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1984;1:1311-1315. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Suerbaum S, Michetti P. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1175-1186. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gisbert JP, Calvet X. Review article: the effectiveness of standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori has not changed over the last decade, but it is not good enough. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1255-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori update: gastric cancer, reliable therapy, and possible benefits. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:719-731.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 32.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chung JW, Lee GH, Han JH, Jeong JY, Choi KS, Kim do H, Jung KW, Choi KD, Song HJ, Jung HY. The trends of one-week first-line and second-line eradication therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:246-250. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, Meddi P, Lionetti R, Hassan C, Ripani C, Tomaselli G, Attili AF. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715-718. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults and children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:3069-3079; quiz 1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yoon H, Lee DH, Kim N, Park YS, Shin CM, Kang KK, Oh DH, Jang DK, Chung JW. Meta-analysis: is sequential therapy superior to standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in Asian adults? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1801-1809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kwon JH, Lee DH, Song BJ, Lee JW, Kim JJ, Park YS, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Lee SH. Ten-day sequential therapy as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: a retrospective study. Helicobacter. 2010;15:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Park HG, Jung MK, Jung JT, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Seo HE, Lee JH, Yang CH, Kim ES, Cho KB. Randomised clinical trial: a comparative study of 10-day sequential therapy with 7-day standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in naïve patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:56-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hsu PI, Wu DC, Wu JY, Graham DY. Modified sequential Helicobacter pylori therapy: proton pump inhibitor and amoxicillin for 14 days with clarithromycin and metronidazole added as a quadruple (hybrid) therapy for the final 7 days. Helicobacter. 2011;16:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sardarian H, Fakheri H, Hosseini V, Taghvaei T, Maleki I, Mokhtare M. Comparison of hybrid and sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication in Iran: a prospective randomized trial. Helicobacter. 2013;18:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Oh DH, Lee DH, Kang KK, Park YS, Shin CM, Kim N, Yoon H, Hwang JH, Jeoung SH, Kim JW. Efficacy of hybrid therapy as first-line regimen for Helicobacter pylori infection compared with sequential therapy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1171-1176. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Current European concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. The Maastricht Consensus Report. European Helicobacter Pylori Study Group. Gut. 1997;41:8-13. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vakil N, Lanza F, Schwartz H, Barth J. Seven-day therapy for Helicobacter pylori in the United States. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:99-107. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Higuchi K, Maekawa T, Nakagawa K, Chouno S, Hayakumo T, Tomono N, Orino A, Tanimura H, Asahina K, Matsuura N. Efficacy and safety of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy with omeprazole, amoxicillin and high- and low-dose clarithromycin in Japanese patients: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre study. Clin Drug Investig. 2006;26:403-414. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Zullo A, Scaccianoce G, De Francesco V, Ruggiero V, D’Ambrosio P, Castorani L, Bonfrate L, Vannella L, Hassan C, Portincasa P. Concomitant, sequential, and hybrid therapy for H. pylori eradication: a pilot study. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2013;37:647-650. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gatta L, Vakil N, Vaira D, Scarpignato C. Global eradication rates for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic review and meta-analysis of sequential therapy. BMJ. 2013;347:f4587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (95)] |

| 19. | Kim JS, Kim BW, Ham JH, Park HW, Kim YK, Lee MY, Ji JS, Lee BI, Choi H. Sequential Therapy for Helicobacter pylori Infection in Korea: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gut Liver. 2013;7:546-551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Keating GM, Scott LJ. Moxifloxacin: a review of its use in the management of bacterial infections. Drugs. 2004;64:2347-2377. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Edlund C, Beyer G, Hiemer-Bau M, Ziege S, Lode H, Nord CE. Comparative effects of moxifloxacin and clarithromycin on the normal intestinal microflora. Scand J Infect Dis. 2000;32:81-85. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Hwang JJ, Lee DH, Lee AR, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N. Efficacy of moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy for first-line eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastrointestinal disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5032-5038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Zullo A, Perna F, Hassan C, Ricci C, Saracino I, Morini S, Vaira D. Primary antibiotic resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated in northern and central Italy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1429-1434. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chung JW, Jung YK, Kim YJ, Kwon KA, Kim JH, Lee JJ, Lee SM, Hahm KB, Lee SM, Jeong JY. Ten-day sequential versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a prospective, open-label, randomized trial. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1675-1680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, Opekun AR, Kuo CH, Wu IC, Wang SS, Chen A, Hung WC, Graham DY. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36-41.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Graham DY, Lee YC, Wu MS. Rational Helicobacter pylori therapy: evidence-based medicine rather than medicine-based evidence. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:177-186.e3; Discussion e12-e13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Graham DY, Shiotani A. New concepts of resistance in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5:321-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. Therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection can be improved: sequential therapy and beyond. Drugs. 2008;68:725-736. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Zullo A, Hassan C, Lorenzetti R, Winn S, Morini S. A clinical practice viewpoint: to culture or not to culture Helicobacter pylori? Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:357-361. [PubMed] |