Published online Aug 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i32.9675

Peer-review started: February 23, 2015

First decision: March 26, 2015

Revised: April 13, 2015

Accepted: June 9, 2015

Article in press: June 10, 2015

Published online: August 28, 2015

Processing time: 188 Days and 21.3 Hours

A 77-year-old Japanese woman was transported to a nearby hospital due to sudden abdominal pain and transient loss of consciousness. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) suggested hemoperitoneum and hepatic nodule. She was conservatively treated. Contrast-enhanced CT two months later revealed an increased mass size, and the enhancement pattern suggested the possibility of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Under a clinical diagnosis of HCC, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) was performed. A subsequent imaging study revealed that most of the lipiodol used for the embolization was washed out. Therefore, surgical resection was performed. Histologically, the nodule contained numerous inflammatory cells including small lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. Notably, epithelioid granulomatous features with multinucleated giant cells were observed in both the nodule and background liver. Some of the multinucleated giant cells contained oil lipid. Among the infiltrating inflammatory cells, spindle-shaped, histiocytoid or myoid tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm were found. The tumor cells were positive for Melan A and HMB45. The nodule contained many IgG4-positive plasma cells; these were counted and found to number 72.6 cells/HPF (range: 61-80). The calculated IgG4:IgG ratio was 33.2%. The nodule was finally diagnosed as previously ruptured inflammatory angiomyolipoma modified by granulomatous reaction after TACE.

Core tip: Hepatic angiomyolipoma (AML) is a rare benign neoplasm. Particularly, the inflammatory variant of hepatic AML is extremely rare. Spontaneous rupture of hepatic AML is also extremely rare phenomenon. The authors herein present a case of spontaneously ruptured hepatic inflammatory AML associated with extensive granulomatous reaction induced by chemoembolization. This case is not only rare, but also suggests that chemoembolization rarely causes granulomatous reaction in hepatic tissue.

- Citation: Kai K, Miyosh A, Aishima S, Wakiyama K, Nakashita S, Iwane S, Azama S, Irie H, Noshiro H. Granulomatous reaction in hepatic inflammatory angiomyolipoma after chemoembolization and spontaneous rupture. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(32): 9675-9682

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i32/9675.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i32.9675

Hepatic angiomyolipoma (AML) is a rare benign neoplasm composed of variable admixtures of adipose tissue, smooth muscle and thick-walled blood vessels which was first described by Ishak in 1976[1]. Hepatic AML is currently considered to be a tumor of perivascular epithelioid cells (PEComa) having myomatous and lipomatous differentiation and melanogenesis[2,3]. Melanocytic markers, such as HMB-45 and Melan A were considered to be promising markers for AML in immunohistochemistry.

According to the differentiation, predominance of tissue components, and growth patterns, AML were subcategorized into classical/mixed, leiomyomatous, lipomatous, myelolipomatous, angiomatous/angiomyomatous, epithelioid, trabecular, oncocytic, pleomorphic and inflammatory variants[3,4]. Of these, the inflammatory variant is extremely rare, and differential diagnosis with other histologically similar tumors such as inflammatory pseudotumors (IPTs), inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs) and follicular dendritic cell (FDC) tumors is necessary[5]. The authors herein present a unique case of spontaneously ruptured hepatic inflammatory AML modified by epithelioid granuloma, the histology of which was previously unreported.

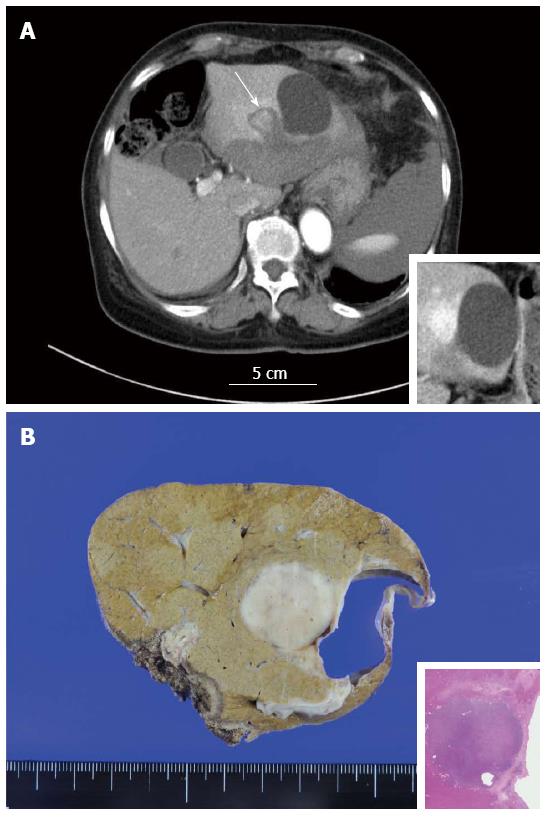

A 77-year-old Japanese woman was transported to a nearby hospital due to sudden abdominal pain and transient loss of consciousness. She had no past medical history except for acute appendicitis 20 years earlier. She had no signs of tuberous sclerosis. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) suggested hemoperitoneum and hepatic nodule. The patient was transferred to our hospital for further examination and treatment. Laboratory tests on admission revealed mild anemia (red blood cell count, 3.60 × 106/μL; hemoglobin concentration, 10.6 g/dL; hematocrit, 25.6%), while the white blood cell and platelet counts were within the normal ranges (6300/μL and 17.7 × 104/μL, respectively). Serology and coagulation tests showed no abnormalities other than the following: total protein, 5.8 g/dL (normal, 6.7-8.3 g/dL); albumin, 3.2 g/dL (normal, 3.8-5.0 g/dL) and C-reactive protein, 1.12 mg/dL (normal, < 0.30 mg/dL). All examined tumor markers were within normal ranges, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and vitamin K absence-II (PIVKA-II). The patient was negative for HBs antigen and HCV antibody but positive for HBc antibody and positive for antimitochondrial antibody (AMA)-M2. The titer of antinuclear antibody (ANA) was 1:160. The serum IgG level was within the normal range. Additional serum examination revealed no elevation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) or of the serum IgG4 level. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT on admission showed subcapsular hematoma at the left lobe of the liver and hemorrhagic ascites around the spleen. A mass-like lesion measuring approximately 1.5 cm in diameter was also noted at segment 2 of the liver adjacent to the simple hepatic cyst (Figure 1A). These findings were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Because of the stability of the patient’s vital signs and the improvement of her anemia, the patient was treated conservatively and discharged on her tenth day in the hospital.

The patient was followed-up with periodic imaging studies. Contrast-enhanced abdominal CT performed two months after the onset revealed an increased mass size (approximately 2.3 cm in diameter) at segment 2 of the liver, and the enhancement pattern (high-low) of the nodule suggested the possibility of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Under a clinical diagnosis of previously ruptured HCC, trancecatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) with miriplatin hydrate and lipiodol was performed at three months after the onset. Subsequent CT and MRI images revealed that most of the lipiodol used for the embolization was washed out. Therefore, surgical resection (laparoscopic left lateral segmentectomy) was performed four months after the onset.

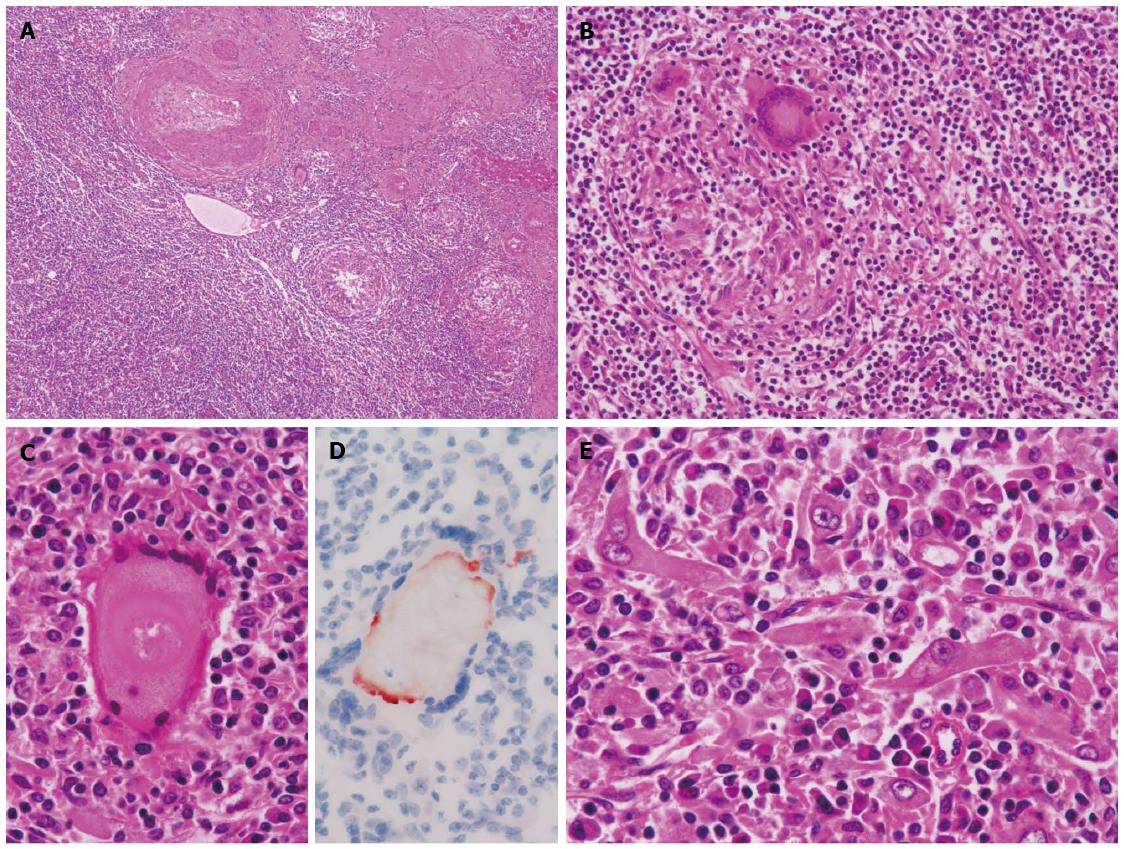

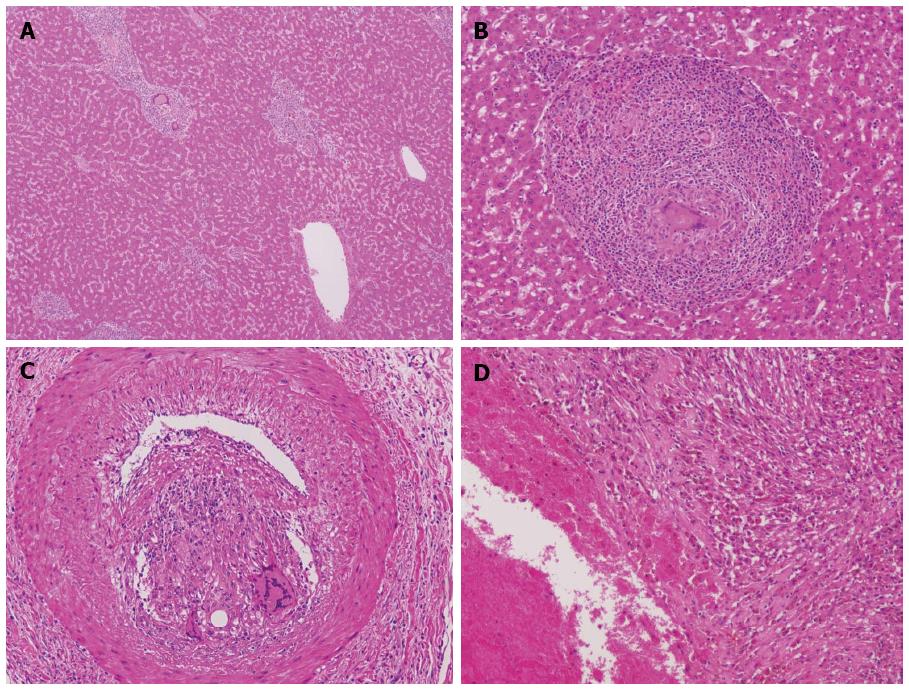

The cut section of the tumor (Figure 1B) revealed a well-demarcated brown to whitish solid mass lesion measuring 2.5 cm in diameter. A simple hepatic cyst was adjacent to the nodule. The nodule contained numerous inflammatory cells including small lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. Thick-walled abnormal arteries were observed peripheral to and inside of the nodule (Figure 2A). Notably, epithelioid granulomatous features, namely epithelioid macrophages and multinucleated giant cells, were frequently observed (Figure 2B). Some of the multinucleated giant cells contained amorphous material which was positively stained by Oil Red O staining (Figure 2C and D). Among infiltrating inflammatory cells, spindle-shaped, histiocytoid or myoid tumor cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and oval-shaped atypical nuclei with distinct nucleoli were found (Figure 2E). Lipomatous tissue was not apparent in the nodule. Mitotic figures and necrosis were not observed. In the background liver, bridging fibrosis, which would suggest the presence of chronic hepatitis, was not observed (Figure 3A). It should be noted that epithelioid granulomas were observed not only in the nodule, but also in many portal tracts in the background liver surrounding the nodule (Figure 3B). Granulomas were observed even in the intima of some hepatic arteries (Figure 3C). Inflammatory granulation tissue containing hemosiderin-laden macrophages and old blood coagula, which were consistent with a previous rupture and hemorrhage, were observed adjacent to the nodule (Figure 3D). The loss of small bile ducts and chronic non-suppurative destructive cholangitis (CNDSC) suggesting primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) were not observed.

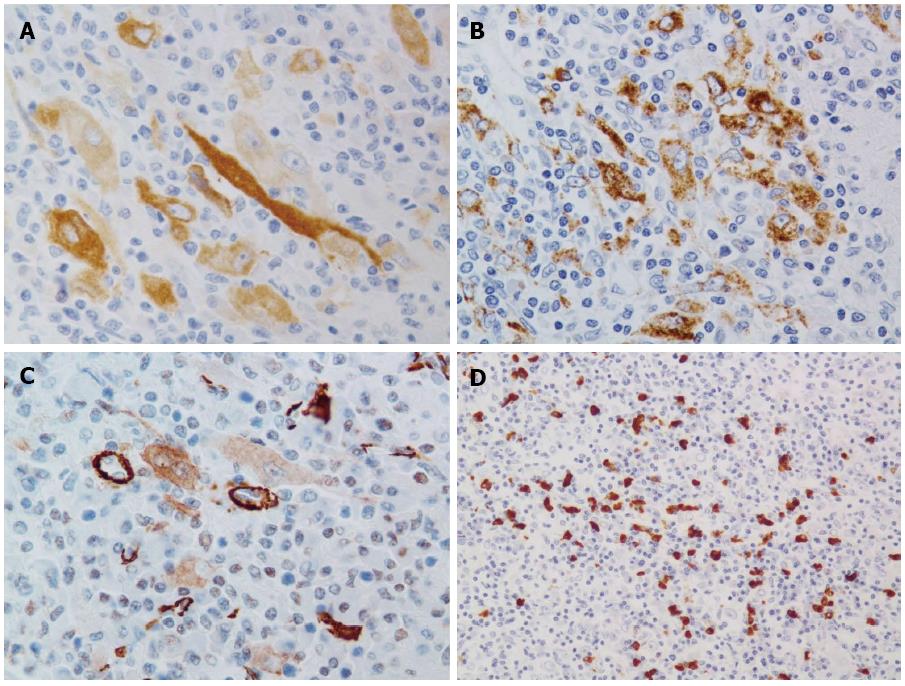

In the immunohistochemical analysis, the tumor cells were positive for vimentin but negative for pan cytokeratin (AE1/AE3), hepatocyte paraffin 1, c-kit and ALK-1. The tumor cells diffusely expressed melan A with various levels of intensity (Figure 4A) and focally expressed HMB45 (Figure 4B). Few tumor cells weakly expressed alpha-SMA (Figure 4C), but desmin was completely negative. Many IgG4-positive plasma cells were observed in the nodule (Figure 4D). The numbers of IgG- and IgG4-positive plasma cells were counted in three hot spots. The average numbers of IgG- and IgG4-positive plasma cells were 219.0 cells/HPF (range: 177-285) and 72.6 cells/HPF (range: 61-80), respectively. The calculated IgG4:IgG ratio was 33.2%. Based on the above histological and immunohistochemical findings, the nodule was finally diagnosed as inflammatory AML modified by granulomatous reaction with multinucleated giant cells.

The patient’s clinical course after surgery was uneventful, and she was discharged from the hospital on the seventh postoperative day. No recurrent tumor has been observed as of the time of this writing (three and a half years after the operation).

An inflammatory variant of hepatic AML was first reported by Kojima et al[5] in 2004. Since then, only eight cases have appeared in the literature in English (Table 1)[5-8]. To make the diagnosis in these cases, it was essential to recognize histiocytoid or myoid tumor cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm among the prominent inflammatory cells and to confirm the expression of melanocytic markers by immunohistochemistry. Recently, a case of hepatic inflammatory AML which suggested an association with IgG4-related pseudotumor was reported[6]. Interestingly, our case also showed an elevated IgG4:IgG ratio; therefore, IgG4-related IPT was initially considered as a differential diagnosis. However, the lack of prominent reticular or storiform fibrosis, a normal serum IgG4 level and the absence of IgG4-positive plasma cells in the background portal tracts were negative findings for IgG4-related IPT[9]. Although in most of the reported hepatic AML cases IgG4-positive plasma cells were not investigated, the relationship between IgG4-positive plasma cells and inflammatory AML is an interesting subject. Other differential diagnoses that were considered in our case were spontaneous necrosis of HCC and tuberculosis. The former was ruled out due to the negativity of hepatocyte paraffin 1 and the absence of a remaining or wrecked tumor component. The latter was ruled out due to the absence of caseous necrosis and the negative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) findings for formalin-fixed tissue from the background liver and tumor.

| Age | Sex | Size/location | Signs of TSC | Clinical diagnosis | Melanocytic markers | Symptom/onset | Treatment | Follow up after surgery | |

| Previous cases of hepatic inflammatory AML (n = 8)[5-8] | 41.3 (mean) | Male: 1 | 6.5 cm (mean) | None (all cases) | IPT (by biopsy): 1 | HMB 45 (+/-): 8/0 | Pyrexia: 2 | Elective resection (all cases) | All cases alive with no recurrence (follow up: 2-7 yr) |

| 21-63 (range) | Female: 7 | 3-10 cm (range) | Mass lesion (without biopsy): 7 | Melan A (+/-): 5/2 | Hepatic mass: 4 | ||||

| Lt. lobe: 5 | Abdominal discomfort: 2 | ||||||||

| Rt. lobe: 3 | |||||||||

| Previous cases of ruptured hepatic AML (n = 7)[3,15-20] | 45.1 (mean) | Male: 3 | 7.9 cm (mean) | Present: 1 | Hepatic tumor: 4 | HMB 45 (+): 2 | Hemorrhagic shock: 2 | Emergent resection: 3 | Alive with no recurrence:1 (follow up: 2 yr) |

| 22-74 (range) | Female: 3 | 5-10.5 cm (range) | None: 6 | Lipomatous tumor: 1 | Melan A (+): 1 | Upper abdominal pain: 3 | Emergent laparotomy for hemostasis: 2 | NA: 6 | |

| NA: 1 | NA: 1 | Lt. lobe: 2 | Hemangioma: 1 | NA (HMB 45): 5 | Unkown:2 | Elective resection after emergent laparotomy for hemostasis: 1 | |||

| Rt. lobe: 5 | Hepatic AML: 1 | NA (Melan A): 6 | Elective resection after TAE: 1 | ||||||

| Present case | 77 | Female | 2.5 cm Lt. lobe | None | HCC (without biopsy) | HMB 45: + | Hemorrhagic shock | Elective resection after TAE | Alive with no recurrence (3 yr) |

| Melan A: + |

Notable features of the present case included the granulomatous reaction and the multinucleated giant cells in both the nodule and the surrounding portal tracts of the background liver. It is known that IPTs sometimes contain multinucleated giant cells[9]. However, hepatic inflammatory AML containing multinucleated giant cells has never been reported[5-8]. The differential diagnoses for multiple granulomas included tuberculosis, systemic sarcoidosis, fungal infection and PBC. Tuberculosis was excluded due to the absence of caseous necrosis and the negative Ziehl-Neelsen stain and negative PCR results obtained using formalin-fixed tissue. Systemic sarcoidosis was ruled out because no lesion was found in radiological examination of the whole body and no elevation of the serum ACE level was observed. Although positive serum AMA-M2 suggested the possibility of PBC, it was ruled out due to the normal levels of serum biliary enzymes (such as γ-glutamyltransferase and alkaline phosphatase) and the negative pathological findings for a lack of small bile ducts and CNDSC. From the above diagnostic ruleouts and the finding that lipid material was confirmed in some multinucleated giant cells, we concluded that the granulomatous reaction of both the tumor and background liver were possibly induced by the intra-arterial injection of a lipiodolized agent. Although embolization is sometimes performed in renal AML, detailed histology has not been investigated after the embolization[10,11]. A few case reports of granulomatous reactions against lipiodol have been published, including one report of granulomas in HCC induced by lipiodolized styrene maleic acid conjugated neocarzinostatin (SMANCS)[12-14]. Consequently, the question arises as to whether inflammatory cells can secondarily infiltrate an ordinary AML as a result of TACE. However, we believe that the present case originally developed as an inflammatory AML because of its similarity to previous hepatic inflammatory AML series in terms of the morphology of the tumor cells and the composition of the inflammatory cells, with the exception of the granulomatous reaction.

Our case involved an outbreak of intraperitoneal bleeding. Hepatic tumors that cause spontaneous rupture and hemoperitoneum are usually HCCs. However, it is known that hepatic AML has also ruptured spontaneously and caused hemoperitoneum in rare cases. We could find only seven previously reported cases of spontaneously ruptured hepatic AML (Table 1)[3,15-20]. The previously reported cases involved large (5-10.5 cm) subcapsular tumors. Our case was also subcapsular but was the smallest (2.5 cm) ruptured hepatic AML among those reported. No ruptured case was found in the previously reported inflammatory AML series.

In summary, we have presented an extremely rare case of a spontaneously ruptured hepatic inflammatory AML modified by a granulomatous reaction after chemoembolization. Present case would be useful reference for the pathologists or clinicians who encounter similar case in the future.

We wish to thank Dr. Osamu Nakashima and Dr. Masayoshi Kage (Department of Pathology, Kurume University) for their valuable comments and advice regarding the pathological diagnosis. This case was presented and discussed at the 328th Kyushu-Okinawa slide conference. We are also grateful to the conference participants for their valuable comments and discussion. English usage in this paper was reviewed by KN international.

A 77-year-old woman was transported to a hospital due to sudden abdominal pain and transient loss of consciousness.

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed hemoperitoneum and hepatic nodule.

Rupture of hepatocellular carcinoma, mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, metastatic liver tumor and other hepatic tumors.

Mild anemia was observed. All examined tumor markers were within normal ranges, including alpha-fetoprotein and vitamin K absence-II.

Clinical diagnosis of ruptured hepatocellular carcinoma was made by the findings of contrast-enhanced abdominal CT.

Among the infiltrating inflammatory cells with epithelioid granulomatous features, tumor cells which were positive for Melan A and HMB45 were found. The nodule was finally diagnosed as previously ruptured inflammatory angiomyolipoma modified by granulomatous reaction after chemoembolization.

Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization was initially performed and then surgical resection (laparoscopic left lateral segmentectomy) was performed.

Only eight cases of hepatic inflammatory angiomyolipoma, seven cases of spontaneously ruptured hepatic angiomyolipoma and a few cases of granulomatous reactions against lipiodol have appeared in the literature in English.

Hepatic angiomyolipoma is a rare benign neoplasm having myomatous and lipomatous differentiation and melanogenesis. Its inflammatory variant is extremely rare.

This report provides valuable experience of hepatic inflammatory angiomyolipoma involving spontaneous rupture and granulomatous reaction due to chemoembolization. We believe present case would be useful reference for the pathologists or clinicians who encounter similar case.

This is a well written case series and literature review. Although the pathological features were well described and literatures were reviewed completely, details of CT manifestations were not well revealed.

P- Reviewer: Chok KSH, Gong JS, Sodergren MH, Zhou YM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Ishak KG. Mesenchymal tumors of the liver. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. New York: John Wiley and Sons 1976; 247-307. |

| 2. | Martignoni G, Pea M, Reghellin D, Zamboni G, Bonetti F. PEComas: the past, the present and the future. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:119-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tsui WM, Colombari R, Portmann BC, Bonetti F, Thung SN, Ferrell LD, Nakanuma Y, Snover DC, Bioulac-Sage P, Dhillon AP. Hepatic angiomyolipoma: a clinicopathologic study of 30 cases and delineation of unusual morphologic variants. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:34-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nonomura A, Enomoto Y, Takeda M, Takano M, Morita K, Kasai T. Angiomyolipoma of the liver: a reappraisal of morphological features and delineation of new characteristic histological features from the clinicopathological findings of 55 tumours in 47 patients. Histopathology. 2012;61:863-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kojima M, Nakamura S, Ohno Y, Sugihara S, Sakata N, Masawa N. Hepatic angiomyolipoma resembling an inflammatory pseudotumor of the liver. A case report. Pathol Res Pract. 2004;200:713-716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Agaimy A, Märkl B. Inflammatory angiomyolipoma of the liver: an unusual case suggesting relationship to IgG4-related pseudotumor. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2013;6:771-779. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Liu Y, Wang J, Lin XY, Xu HT, Qiu XS, Wang EH. Inflammatory angiomyolipoma of the liver: a rare hepatic tumor. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Shi H, Cao D, Wei L, Sun L, Guo A. Inflammatory angiomyolipomas of the liver: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical analysis of 5 cases. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2010;14:240-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Deshpande V, Zen Y, Chan JK, Yi EE, Sato Y, Yoshino T, Klöppel G, Heathcote JG, Khosroshahi A, Ferry JA. Consensus statement on the pathology of IgG4-related disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:1181-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1714] [Cited by in RCA: 1771] [Article Influence: 136.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Huang Q, Zhai RY. Embolization of symptomatic renal angiomyolipoma with a mixture of lipiodol and PVA, a mid-term result. Chin J Cancer Res. 2014;26:399-403. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hocquelet A, Cornelis F, Le Bras Y, Meyer M, Tricaud E, Lasserre AS, Ferrière JM, Robert G, Grenier N. Long-term results of preventive embolization of renal angiomyolipomas: evaluation of predictive factors of volume decrease. Eur Radiol. 2014;24:1785-1793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ichikawa T, Takagi H, Yamada T, Abe T, Ito H, Kojiro M, Mori M. Granulomas in hepatocellular carcinoma induced by lipiodolized SMANCS, a polymer-conjugated derivative of neocarzinostatin. Histopathology. 2002;40:579-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shigetaka Y, Masatsugu S, Yoshikuni F, Yoshihiro T. Parotid and pterygomaxillary lipogranuloma caused by oil-based contrast medium used for sialography: report of a case. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1996;54:350-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Grosskinsky CM, Clark RL, Wilson PA, Novotny DB. Pelvic granulomata mimicking endometriosis following the administration of oil-based contrast media for hysterosalpingography. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:890-892. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Huber C, Treutner KH, Steinau G, Schumpelick V. Ruptured hepatic angiolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1996;381:7-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Guidi G, Catalano O, Rotondo A. Spontaneous rupture of a hepatic angiomyolipoma: CT findings and literature review. Eur Radiol. 1997;7:335-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zhou YM, Li B, Xu F, Wang B, Li DQ, Zhang XF, Liu P, Yang JM. Clinical features of hepatic angiomyolipoma. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2008;7:284-287. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ding GH, Liu Y, Wu MC, Yang GS, Yang JM, Cong WM. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatic angiomyolipoma. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:807-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Occhionorelli S, Dellachiesa L, Stano R, Cappellari L, Tartarini D, Severi S, Palini GM, Pansini GC, Vasquez G. Spontaneous rupture of a hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: damage control surgery. A case report. G Chir. 2013;34:320-322. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Tajima S, Suzuki A, Suzumura K. Ruptured hepatic epithelioid angiomyolipoma: a case report and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2014;7:369-375. [PubMed] |