Published online Aug 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9367

Peer-review started: December 5, 2014

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: February 28, 2015

Accepted: April 28, 2015

Article in press: April 28, 2015

Published online: August 21, 2015

Processing time: 258 Days and 12 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether administration of Ringer’s solution (RL) could have an impact on the outcome of acute pancreatitis (AP).

METHODS: We conducted a retrospective study on 103 patients [68 men and 35 women, mean age 51.2 years (range, 19-92 years)] hospitalized between 2011 and 2012. All patients admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Interior (Poland) with a diagnosis of AP who had disease onset within 48 h of presentation were included in this study. Based on the presence of persistent organ failure (longer than 48 h) as a criterion for the diagnosis of severe AP (SAP) and the presence of local complications [diagnosis of moderately severe AP (MSAP)], patients were classified into 3 groups: mild AP (MAP), MSAP and SAP. Data were compared between the groups in terms of severity (using the revised Atlanta criteria) and outcome. Patients were stratified into 2 groups based on the type of fluid resuscitation: the 1-RL group who underwent standard fluid resuscitation with a RL 1000 mL solution or the 2-NS group who underwent standard fluid resuscitation with 1000 mL normal saline (NS). All patients from both groups received an additional 5% glucose solution (1000-1500 mL) and a multi-electrolyte solution (500-1000 mL).

RESULTS: We observed 64 (62.1%) patients with MAP, 26 (25.24%) patients with MSAP and 13 (12.62%) patients with SAP. No significant difference in the distribution of AP severity between the two groups was found. In the 1-RL group, we identified 22 (55.5%) MAP, 10 (25.5%) MSAP and 8 (20.0%) SAP patients, compared with 42 (66.7%) MAP, 16 (24.4%) MSAP and 5 (7.9%) SAP cases in the 2-NS group (P = 0.187). The volumes of fluid administered during the initial 72-h period of hospitalization were similar among the patients from both the 1-RL and 2-NS groups (mean 3400 mL vs 3000 mL, respectively). No significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups were found in confirmed pancreatic necrosis [10 patients (25%) vs 12 patients (19%), respectively, P = 0.637]. There were no statistically significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups in the percentage of patients who required enteral nutrition (23 patients vs 17 patients, respectively, P = 0.534). Logistic regression analysis confirmed these findings (OR = 1.344, 95%CI: 0.595-3.035, P = 0.477). There were no significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups in mortality and the duration of hospital stay (median of 9 d for both groups, P = 0.776).

CONCLUSION: Our study failed to find any evidence that the administration of RL in the first days of AP leads to improved clinical outcomes.

Core tip: To date, only a handful of studies have focused on the effect of Ringer’s solution in the treatment of acute pancreatitis (AP). We believe that our findings could be of interest to the readers because they may allow for a more reliable review of a complex area of fluid resuscitation in the setting of AP compared with existing studies. These results were mainly achieved by applying the modified Atlanta score in our study, which includes “end points” focused on the final AP treatment outcome rather than only on changes in a single laboratory parameter and clinical signs.

- Citation: Lipinski M, Rydzewska-Rosolowska A, Rydzewski A, Rydzewska G. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: Normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution? World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(31): 9367-9372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i31/9367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i31.9367

Fluid therapy is a crucial aspect of the management of patients with acute pancreatitis (AP), especially in the early hours of the disease. Crystalloids are currently recommended as the initial resuscitation fluids in patients with AP. Nevertheless, the optimal type of fluid therapy remains unclear. The composition, volume and rate of fluid administration that is most appropriate for the treatment of AP is currently being debated[1].

Isotonic crystalloids, particularly normal saline (NS), are commonly used as the preferred first-line fluid treatment for patients with AP[2,3]. NS is an isotonic solution (osmolality 308 mOsm/L) with a nominal pH of 5.5 (4.5-7.0). However, balanced crystalloid lactated Ringer’s solution (RL) may be more beneficial than NS[4] as it reduces the risk of hyperchloremic acidosis associated with impaired renal function.

Experimental studies show that zymogens may be activated by low pH. Furthermore, low pH may also adversely impact acinar cells and make them more vulnerable to injury, thereby contributing to the increase in severity of AP[5]. From that perspective, RL with its pH (normal range, 6.0-7.5) may potentially provide for the protective effects on tissue and improve the outcome of AP.

In AP, hypovolemia is associated with an increased risk of tissue hypoperfusion and the development of organ failure[6]. There is a hypothesis based on the analysis of a study on the experimental model of AP, which assumes that intensive fluid resuscitation can reduce the extent of hypoperfusion[7]. Fluid replacement in the setting of SAP is intended not only to replace the deficiency in blood volume but also to stabilize capillary permeability, maintain the function of the intestinal barrier[8] and modulate the inflammatory response[9].

In the assessment of AP prognosis, there is a tendency to consider factors that reflect the intravascular volume depletion [serum creatinine, eGFR, BUN, urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (uNGAL)], which often present during the first hours of AP[10-14].

Hypovolemia is one of the major pathological symptoms associated with early stage AP; however, there is no conclusive research that would suggest the use of a specific fluid therapy in AP. The type of solution recommended as the initial fluid therapy has been a subject of ongoing debate for many years. The current recommendations do not specify the precise strategy for fluid therapy in AP.

Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the effect of type of fluid therapy on SAP outcome.

We conducted a retrospective study on 103 patients [68 men and 35 women, mean age 51.2 years (range, 19-92 years)] hospitalized between 2011 and 2012. All patients admitted to the Department of Gastroenterology of the Central Clinical Hospital of the Ministry of Interior (Poland) with a diagnosis of AP who had disease onset within 48 h of presentation were included in this study. Transferred patients or those patients with symptoms lasting more than 48 h were excluded. A total of 103 patients were divided into 2 groups based on whether or not they received early RL (1000 mL/24 h, initiated within 24 h of admission for a duration of 3 d): 40 patients received early RL (1-RL group), while 63 patients did not (2-NS group). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to demographic data including age, sex and BMI (Table 1).

| 1-RL group (n = 40) | 2-NS group (n = 63) | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 49.2 ± 18.0 | 52.5 ± 17.6 |

| Male | 30 (75) | 38 (60.3) |

| Female | 10 (25) | 25 (39.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 27.6 ± 5.0 | 26.3 ± 5.4 |

The aetiology of AP in the 1-RL group was biliary in 14 patients (35%), alcoholic in 23 patients (57.5%), and other (post-ERCP, idiopathic, hereditary, etc.) in 3 patients (7.5%). In the 2-NS group, the aetiology of AP was biliary in 29 patients (46.1%), alcoholic in 16 patients (25.5%), and other in 18 patients (28.4%).

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on the type of fluid resuscitation: the 1-RL group who underwent standard fluid resuscitation with RL 1000 mL solution or the 2-NS group who underwent standard fluid resuscitation with 1000 mL NS. All patients from both groups received additional 5% glucose solution (1000-1500 mL) and a multi-electrolyte solution (500-1000 mL). The use of RL or NS was dictated only by experience and conviction of the physicians prescribing fluid for the particular patient. No additional clinical or other types of criteria were applied. No specific protocol indicating the need for a specific fluid therapy was applied. In case when intravenous hydration was still necessary after 72 h - patient consistently received NS or RL with additional crystalloids previously described.

Because the study involved the assessment of fluid therapy in the first 3 d of AP, the prognostic methods used in predicting the course of pancreatitis had to be already applied in the first stage of the disease. Therefore, it was decided that the BISAP score and uNGAL values be used. The BISAP score was determined in all patients within the first 24 h of admission. Urine samples obtained from 24-h urine collections were gathered for determination of the urinary level of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin from the first day. We did not exclude geriatric patients (over 65 years of age) due to the negative impact of such a decision on the credibility of the BISAP scale prediction.

The crystalloids used in the study (NS, RL, multi-electrolyte solution) were commercially-available products (manufactured by Frescenius Kabi Polska) and were provided from a hospital pharmacy.

Based on the presence of persistent organ failure (more than 48 h) as a criterion for the diagnosis of severe AP (SAP) and the presence of local complications [diagnosis of moderately severe AP (MSAP)], patients were classified into 3 groups: mild AP (MAP), MSAP and SAP. Organ failure was identified using the Modified Marshall Scoring System. Data were compared between the groups in terms of severity (using the revised Atlanta criteria) and outcome. Primary endpoints of the study were the distribution of AP severity, mortality and pancreatic necrosis, while secondary endpoints were the percentage of patients requiring enteral nutrition and the duration of hospital stay.

The χ2 test and Fisher exact test were used to compare the distribution of patient characteristics. The risk score was developed using a logistic regression model. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Overall survival of these patients was examined using log-rank tests.

There were no statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients with predicted SAP in the 1-RL and 2-NS groups using the BISAP score (Table 2). SAP was predicted using the BISAP score in 8 patients (20%) from the 1-RL group and in 8 patients (12.7%) from the 2-NS group (P = 0.405).

| 1-RL | 2-NS | P value | |

| BISAP ≥ 3 | 8 (20.0) | 8 (12.7) | 0.405 |

| uNGAL ≥ 73 ng/mL | 15 (37.5) | 11 (17.5) | 0.035 |

Using the concentration of NGAL in the urine as a prognostic parameter, SAP was predicted in 15 patients (37.5%) from the 1-RL group and 11 patients (17.5%) from the 2-NS group (P = 0.035).

We observed 64 (62.1%) patients with MAP, 26 (25.24%) patients with MSAP and 13 (12.62%) patients with SAP. No significant difference in the distribution of AP severity between the two groups was found. In the 1-RL group, we identified 22 (55.5%) MAP, 10 (25.5%) MSAP and 8 (20.0%) SAP patients, compared with 42 (66.7%) MAP, 16 (24.4%) MSAP and 5 (7.9%) SAP cases in the 2-NS group (P = 0.187, Table 3).

| P = 0.187 | Total(n = 103) | 1-RL group(n = 40) | 2-NS group(n = 63) |

| Mild AP | 64 (62.1) | 22 (55.5) | 42 (66.7) |

| Moderate AP | 26 (25.24) | 10 (25.5) | 16 (24.4) |

| Severe AP | 13 (12.62) | 8 (20.0) | 5 (7.9) |

The volumes of fluid administered during the first 24 and 72 h of hospitalization were similar among patients from the 1-RL and 2-NS groups (mean 3400 and 10000 vs 3000 and 9000 mL, respectively).

Clinical data for both groups are shown in Table 4. No significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups were found in confirmed pancreatic necrosis [10 patients (25%) vs 12 patients (19%), respectively, P = 0.637].

| 1-RL | 2-NS | P value | |

| Pancreatic necrosis | 10 (25.0) | 12 (19) | 0.637 |

| Enteral nutrition | 23 (57.5) | 17 (27) | 0.534 |

| Hospital stay | 9 d | 9 d | 0.776 |

| Fatal AP | 5 (12.5) | 3 (4.7) | 0.256 |

There were no statistically significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups in the percentage of patients requiring enteral nutrition (23 patients vs 17 patients, respectively, P = 0.534). Logistic regression analysis also confirmed this calculation (OR = 1.344, 95%CI: 0.595-3.035, P = 0.477).

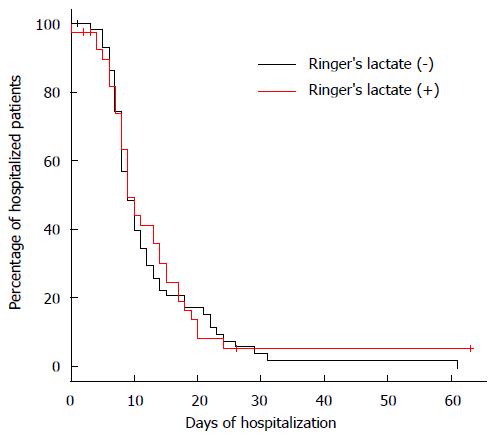

There were no significant differences between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups in the duration of hospital stay (median of 9 d for both groups, P = 0.776) (Figure 1) and mortality (fatal AP in 5 patients vs 3 patients, P = 0.256; OR = 2.857, 95%CI: 0.643-12.687, P = 0.168).

There is still a debate concerning the optimal fluid therapy for the early phase of AP. Administered solutions should not only improve hemodynamic parameters but also exert positive effects on the microcirculation and metabolic processes. The type of fluid, crystalloid and/or colloid, preferred in the early hours of AP remains under discussion.

NS may contribute to the development of metabolic acidosis when administered in large volumes; in contrast, RL does not produce a similar effect. Taking into account the above findings, it is important to remember that SAP is often associated with coexisting metabolic acidosis[11,12]. To date, only a handful of studies have focused on the effect of RL for the treatment of AP[3,13]. Interestingly, most of these studies evaluated only the effects of selected fluid therapy on single prognostic parameters or symptoms and did not assess the impact on the results of the treatment.

The main objective of our study was to investigate the effects of a NS-based vs a RL-based fluid therapy on outcomes in AP.

No statistically significant difference was demonstrated between the 1-RL and 2-NS groups for AP severity. Most of the studies concerning the prognosis of AP conducted to date have not utilized the new criteria to classify disease severity. In this study, patients were retrospectively analysed from the time of hospital admission until discharge or death, as required by the revised Atlanta criteria, which includes persistent organ failure as an essential component[14]. Evaluation of patients based on the revised Atlanta criteria is associated with a lower percentage of patients with a diagnosis of SAP (indicating persistent organ failure). For this reason, the proportion of patients with SAP is less than the observations conducted by 2012. Moreover, the mortality rate in this group is higher because the eligibility criteria for this group indicate a high risk of death.

Differences in the proportion of patients with predicted SAP in the 1-RL and 2-NS groups also were not statistically significant. Our study did not confirm that the administration of RL had more favourable effects than NS with respect to the treatment and outcomes of AP. Our results indicate that, in terms of confirmed pancreatic necrosis, there were no statistically significant differences between the two study groups. These findings are particularly interesting in view of a major role of hypoperfusion in the pathogenesis of not only pancreatic necrosis but also organ failure[6,15,16].

Also notable is the result suggesting that RL does not significantly impact the need for enteral nutrition, when necessary[17]. Therefore, the outcome of the study does not confirm that RL may effectively modulate therapeutic management with regard to enteral nutrition.

It was difficult to demonstrate the beneficial effects of RL on the reduction of mortality in our analysis. We decided to calculate the influence of intravenous hydration on the risk of metabolic acidosis, which is directly related to the risk of death[18,19]. Using this approach, our study failed to find any benefits of using RL solution, compared to 0.9% sodium chloride solution, on the duration of hospital stay and mortality.

It is important to emphasize that the volumes of fluid administered in both groups during the first 72 h of hospitalization were similar. This finding excludes the possibility of differences in the IV fluid volume administered having an impact on the outcome of the study. Our study was retrospective and was not associated with specific recommendations for the hydration of patients that considered their body weight. It is worth noting that intensive fluid resuscitation may lead to tissue oedema and result in organ failure[20,21]. Furthermore, the study groups were different in terms of percentage of patients with prognosed SAP, with the 1-RL group having a higher proportion.

Although the arterial pH of patients from either group was not controlled during their stay at the hospital, we assume that potential changes in pH and acidosis coexisting with AP (expected particularly in the 2-NS group) were not significant. If present, these changes may have been temporary and did not impact the results in either group.

Answers to the question of what is the optimal type of fluid resuscitation in AP and if crystalloid or colloid solutions are more beneficial are still under debate. Recently, a controversy concerning the specific fluid resuscitation protocol in AP was raised by studies using hydroxyethyl starch, which may be associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients[22]. Indeed, the initial fluid resuscitation protocol can have more direct impact on necrosis than mortality. On the other hand, studies exist that support the effectiveness of a mixed ratio of crystalloid-colloid fluid resuscitation in improving the prognosis of patients with SAP[23] and reducing the risk of threatening complications (intra-abdominal hypertension) caused by hydroxyethyl starch[14].

Our study has several limitations. First, it was a retrospective study and our data came from one centre with a limited number of patients. Second, we did not control the arterial pH in our study groups due to retrospective nature of our study (arterial pH was not controlled for all patients in this cohort). It is possible that the volume of RL (1000 mL) used was not sufficient to achieve the target of modulating local pH or alleviating the acidosis in AP.

Also notable is the result achieved using the concentration of NGAL in the urine as a prognostic parameter of SAP. We found statistically significant differences in the proportion of patients with predicted SAP in the 1-RL and 2-NS groups (15 patients vs 11 patients, P = 0.035). A greater proportion of patients with predicted SAP (classified using NGAL but not the BISAP score) in the 1-RL group could also make it more difficult to demonstrate the benefits of RL. Moreover, a greater proportion of patients in the 1-RL group with an alcoholic aetiology (57.5% vs 25.5%) complicates the interpretation of the pancreatic necrosis results. Including a larger number of patients would probably produce more conclusive results.

Nevertheless, our results allow for a more reliable review of a complex area of fluid resuscitation in the setting of AP compared with existing studies. This improvement was mainly achieved by applying the modified Atlanta score in our study, which includes “end points” focused on the final AP treatment outcome rather than only on changes of single laboratory parameters and clinical signs.

Additional studies are needed to provide further data on the benefits and risks of specific fluid regimens in patients with AP. Until the outcomes of such studies are published, the management of AP patients should probably focus more on ensuring that sufficient fluid volume is provided to maintain perfusion rather than on which type of fluid (crystalloids or colloids) is used to achieve it.

Fluid therapy is a crucial aspect of the management of patients with acute pancreatitis (AP), especially in the early hours of the disease. Crystalloids are currently recommended as initial resuscitation fluids for patients with AP. Nevertheless, the optimal type of fluid therapy remains unclear. Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the effect of the type of fluid therapy on SAP outcome.

Hypovolemia is one of the major pathological symptoms associated with the early stages of AP; however, there is no conclusive research that would suggest the use of a specific fluid therapy in AP.

To date, only a handful of studies have focused on the effect of Ringer’s solution in the treatment of AP. Interestingly, most of these studies evaluated only the effects of selected fluid therapy on individual prognostic parameters or symptoms and did not assess the impact on the results of the treatment. In this study, data were compared between groups receiving different treatments in terms of severity (revised Atlanta criteria) and outcomes.

Current results allow for a more reliable review of a complex area of fluid resuscitation in the setting of AP compared with existing studies. Additional studies are needed to provide further data on the benefits and risks of specific fluid regimens in patients with AP.

The composition, volume and rate of fluid administration that is most appropriate for the treatment of AP is currently being debated, particularly for the early phase of AP. Administered solution should not only improve the hemodynamic parameters but also exert positive effects on the microcirculation and metabolic processes.

This study was designed to investigate the effect of the type of fluid therapy on SAP outcomes. This paper addresses an important gap in the literature regarding fluid therapy for AP.

P- Reviewer: Berger Z, Rakonczay Z, Zhao QH S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Haydock MD, Mittal A, Wilms HR, Phillips A, Petrov MS, Windsor JA. Fluid therapy in acute pancreatitis: anybody’s guess. Ann Surg. 2013;257:182-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aggarwal A, Manrai M, Kochhar R. Fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:18092-18103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Vege SS. Current controversies in fluid resuscitation in acute pancreatitis: a systematic review. Pancreas. 2012;41:827-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wu BU, Hwang JQ, Gardner TH, Repas K, Delee R, Yu S, Smith B, Banks PA, Conwell DL. Lactated Ringer’s solution reduces systemic inflammation compared with saline in patients with acute pancreatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:710-717.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Bhoomagoud M, Jung T, Atladottir J, Kolodecik TR, Shugrue C, Chaudhuri A, Thrower EC, Gorelick FS. Reducing extracellular pH sensitizes the acinar cell to secretagogue-induced pancreatitis responses in rats. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1083-1092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Petejova N, Martinek A. Acute kidney injury following acute pancreatitis: A review. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub. 2013;157:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Klar E, Messmer K, Warshaw AL, Herfarth C. Pancreatic ischaemia in experimental acute pancreatitis: mechanism, significance and therapy. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1205-1210. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Capurso G, Zerboni G, Signoretti M, Valente R, Stigliano S, Piciucchi M, Delle Fave G. Role of the gut barrier in acute pancreatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46 Suppl:S46-S51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhao G, Zhang JG, Wu HS, Tao J, Qin Q, Deng SC, Liu Y, Liu L, Wang B, Tian K. Effects of different resuscitation fluid on severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2044-2052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lipinski M, Rydzewski A, Rydzewska G. Early changes in serum creatinine level and estimated glomerular filtration rate predict pancreatic necrosis and mortality in acute pancreatitis: Creatinine and eGFR in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharma V, Shanti Devi T, Sharma R, Chhabra P, Gupta R, Rana SS, Bhasin DK. Arterial pH, bicarbonate levels and base deficit at presentation as markers of predicting mortality in acute pancreatitis: a single-centre prospective study. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014;2:226-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pant N, Kadaria D, Murillo LC, Yataco JC, Headley AS, Freire AX. Abdominal pathology in patients with diabetes ketoacidosis. Am J Med Sci. 2012;344:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Du XJ, Hu WM, Xia Q, Huang ZW, Chen GY, Jin XD, Xue P, Lu HM, Ke NW, Zhang ZD. Hydroxyethyl starch resuscitation reduces the risk of intra-abdominal hypertension in severe acute pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2011;40:1220-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4342] [Article Influence: 361.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 15. | Kozieł D, Kozłowska M, Deneka J, Matykiewicz J, Głuszek S. Retrospective analysis of clinical problems concerning acute pancreatitis in one treatment center. Prz Gastroenterol. 2013;8:320-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Patschan D, Müller GA. Acute kidney injury. J Inj Violence Res. 2015;7:19-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kosel J, Kosciuczuk U, Siemiatkowski A. Wpływ leczenia zywieniowego na funkcjonowanie układu immunologicznego. Prz Gastroenterol. 2013;8:147-155. |

| 18. | Jung B, Rimmele T, Le Goff C, Chanques G, Corne P, Jonquet O, Muller L, Lefrant JY, Guervilly C, Papazian L. Severe metabolic or mixed acidemia on intensive care unit admission: incidence, prognosis and administration of buffer therapy. A prospective, multiple-center study. Crit Care. 2011;15:R238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adeva-Andany MM, Fernández-Fernández C, Mouriño-Bayolo D, Castro-Quintela E, Domínguez-Montero A. Sodium bicarbonate therapy in patients with metabolic acidosis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:627673. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kuwabara K, Matsuda S, Fushimi K, Ishikawa KB, Horiguchi H, Fujimori K. Early crystalloid fluid volume management in acute pancreatitis: association with mortality and organ failure. Pancreatology. 2011;11:351-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de-Madaria E, Soler-Sala G, Sánchez-Payá J, Lopez-Font I, Martínez J, Gómez-Escolar L, Sempere L, Sánchez-Fortún C, Pérez-Mateo M. Influence of fluid therapy on the prognosis of acute pancreatitis: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1843-1850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Perel P, Roberts I, Ker K. Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD000567. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Chang YS, Fu HQ, Zou SB, Yu BT, Liu JC, Xia L, Lv NH. [The impact of initial fluid resuscitation with different ratio of crystalloid-colloid on prognosis of patients with severe acute pancreatitis]. Zhonghua Weizhongbing Jijiu Yixue. 2013;25:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |