Published online Aug 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9150

Peer-review started: January 30, 2015

First decision: April 13, 2015

Revised: April 23, 2015

Accepted: June 15, 2015

Article in press: June 16, 2015

Published online: August 14, 2015

Processing time: 210 Days and 14.3 Hours

AIM: To determine the impact of a clinical pathway (CP) on acute pancreatitis (AP) treatment outcome.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis of medical records was performed. We compared the results of AP treatment outcome over two time periods in our centre, before (2006-2007) and after (2010-2012) the implementation of a CP. The CP comprised the following indicators of quality: performance of all laboratory tests on admission (including lipids and carbohydrate deficient transferrin), determination of AP aetiology, abdomen ultrasound (US) within the first 24 h after admission, contrast-enhanced computed tomography of the abdomen in all cases of suspected pancreatic necrosis, appropriately selected and sufficiently used antibiotic therapy (if necessary), pain control, adequate hydration, control of haemodynamic parameters and transfer to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) (if necessary), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in biliary AP, surgical treatment (if necessary), and advice on outpatient follow-up after discharge. A comparison of the length of stay with that in other Slovenian hospitals was also performed.

RESULTS: There were 139 patients treated in the three-year period after the introduction of a CP, of which 81 (58.3%) were male and 58 (41.7%) female. The patients’ mean age was 59.6 ± 17.3 years. The most common aetiologies were alcoholism and gallstones (38.8% each), followed by unexplained (11.5%), drug-induced, hypertriglyceridemia, post ERCP (2.9% each) and tumours (2.2%). Antibiotic therapy was prescribed in 72 (51.8%) patients. Abdominal US was performed in all patients within the first 24 h after admission. Thirty-two (23.0%) patients were treated in the ICU. Four patients died (2.9%). In comparison to 2006-2007, we found an increased number of alcoholic and biliary AP and an associated decrease in the number of unexplained aetiology cases. The use of antibiotics also significantly decreased after the implementation of a CP (from 70.3% to 51.8%; P = 0.003). There was no statistically significant difference in mortality (1.8% vs 2.9%). The length of stay was significantly shorter when compared to the Slovenian average (P = 0.018).

CONCLUSION: The introduction of a CP has improved the treatment of patients with AP, as assessed by all of the observed parameters.

Core tip: We wanted to improve the quality and streamline the process of treatment in patients with acute pancreatitis (AP) by introducing a clinical pathway (CP) and control of indicators of quality (IOQ). Our results showed that the use of a CP and control of IOQ improved the treatment of patients with AP, as assessed by the following observed parameters: reduced length of stay, reduced percentage of unexplained aetiology cases and reduced use of antibiotic therapy (without changes in total mortality).

- Citation: Vujasinovic M, Makuc J, Tepes B, Marolt A, Kikec Z, Robac N. Impact of a clinical pathway on treatment outcome in patients with acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(30): 9150-9155

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i30/9150.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9150

Acute pancreatitis (AP) is the acute inflammation of the pancreas that can extend to the peripancreatic tissue and distant organs. AP is clinically manifested as abdominal pain with elevated pancreatic enzymes[1].

The incidence of AP varies widely between different countries, ranging from 13 to 73/100000 inhabitants[2-6]. In the United States, AP is the most common cause of hospitalisation for gastrointestinal diseases (274119 admissions in 2012) with an estimated cost of 2.6 billion dollars annually[7].

The new Atlanta classification divides AP according to morphological changes and severity of the disease[8].

From January 1, 2010, we analysed the indicators of quality (IOQ) of a clinical pathway (CP) in the medical records of all patients with AP. The analysis was conducted by a specialist in internal medicine with a subspecialisation in gastroenterology. Our institution is a hospital at the secondary level in an area with approximately 100000 inhabitants. With the introduction of a CP, we wanted to improve the quality of treatment of patients with AP and streamline the process of treatment. This article presents the results of a three-year period after the introduction of a CP and a comparison with the previous period (2006-2007).

We conducted an analysis of the medical records of all patients who were treated for AP in the period from January 1, 2006 to December 31, 2007 and from January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2012.

We included patients with clear diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of AP (abdominal pain, and at least a three-fold increase in activity of amylase and lipase)[1] The following demographics and clinical parameters were analysed: laboratory tests (haemogram, potassium, sodium, chloride, calcium, urea, creatinine, C-reactive protein, liver function tests, amylase, lipase, cholesterol, triglycerides, carbohydrate deficient transferrin, and blood coagulation factors), aetiology of AP, the performance of abdominal ultrasound (US) within the first 24 h after admission, the performance of contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen in all patients with suspected necrotising form of disease (but not in the first 48 h after admission), prescribing of antibiotic therapy, pain management, adequate hydration of the patient, the regular control of vital signs (blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation on room air, temperature, respiratory rate and level of consciousness), transfer of patient to the intensive care unit (ICU) in the case of haemodynamic instability, performing an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in patients with biliary aetiology of AP, consultation with abdominal surgeons in necrotising AP, and outcome of treatment.

After analysing the period 2010-2012 (after the introduction of the CP), we performed a statistical comparison with the period from 2006 to 2007 in the same institution (before the introduction of the CP), as well as a comparison with other Slovenian hospitals (number of patients treated per year, length of stay and mortality).

The analysis of medical records was approved by the General Hospital Slovenj Gradec ethics committee.

Statistical analysis was performed with the statistical program SPSS, version 20. For testing independent and continuous variables, we used the t-test. The relationship of nominal variables was tested by Pearson’s χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact probability test. A probability of less than 5% was taken to indicate statistical significance.

There were 139 patients who were treated in the three-year period (2010-2012) after the introduction of the CP, among whom 105 (75.5%) were patients with a first attack. The most common aetiologies of AP were alcohol and gallstones (Table 1). We found a statistically significantly change in AP aetiology between the two periods. There was an increase in alcoholic pancreatitis and gallstones, and a decrease in unexplained aetiology, in 2010-2012, compared with 2006-2007. The differences in the structure were statistically significant (χ2 = 39.398, df = 3, P = 0.000). There were significant increases in the proportion of alcoholic aetiology and gallstones (P = 0.000). The aetiology of the disease was related to the gender of the patients (Fisher exact probability test = 44.329, P = 0.000), with biliary being a more frequent cause in women (61%) and alcohol being a more frequent cause in men (89%). The average age of patients with alcoholic aetiology was 50 ± 12.6 years, and they were, on average, 19.5 years younger than the patients with biliary aetiology of AP (t-test = 12.819, P = 0.000).

| Aetiology | Period 2006-2007 | Period 2010-2012 | χ2test | P value |

| Unexplained | 52 (46.8) | 16 (11.5) | 47.21 | 0.000 |

| Alcohol | 27 (24.3) | 54 (38.8) | ||

| Gallstones | 23 (20.7) | 54 (38.8) | ||

| Drug-induced | 5 (4.5) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| Pancreas divisum | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | ||

| Post-ERCP | 2 (1.8) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| Cancer | 0 (0) | 3 (2.2) | ||

| Hyperlipemic | 0 (0) | 4 (2.9) | ||

| All | 111 (100.0) | 139 (100.0) |

The average age of patients in the 2010-2012 period was 5 years higher than in 2006-2007 (P < 0.05). The most common morphological form of the AP in the period 2010-2012 was interstitial oedematous pancreatitis, which was observed 84 (60.4%) patients. Acute peripancreatic fluid collection was present in 36 (25.9%) patients, necrotising pancreatitis in 17 (12.2%) patients and pancreatic pseudocysts in two (1.4%) patients.

Pain medication and the infusion of crystalloid solutions with regular controls of vital parameters at least three times a day for the first 24 to 48 h (blood pressure, heart rate, blood oxygen saturation, diuresis) were performed in all patients. Abdominal US was performed in all patients in the first 24 h after admission. CT of the abdomen was performed in 57 (41%) patients, in whom abdominal US findings were suspected for necrosis. All haemodynamically unstable patients were transferred to the ICU (23.0%). The average duration of antibiotic treatment in the period 2010 to 2012 was 8.6 ± 4.4 d. There was a statistically significant (P = 0.003) reduction in the prescription of antibiotics between the two periods, but without any statistically significant change in mortality (Table 2). The most frequent prescription was a combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole (80.6%), followed by amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (9.7%), and imipenem (9.7%).

During the second period, four patients (2.9%) died, including a mentally retarded younger patient with recurrent exacerbations of hyperlipemic AP, and three older patients with biliary AP.

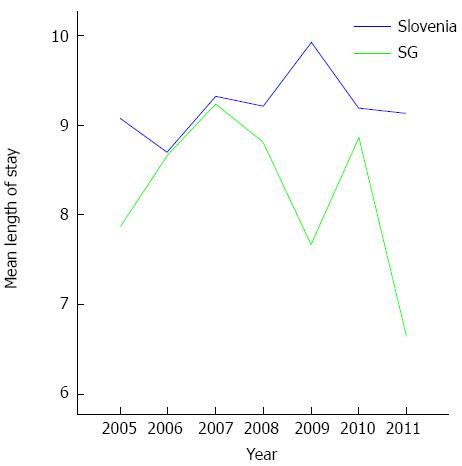

In the period between 2005 and 2011, we treated an average of 910 patients per year in all Slovenian hospitals. In our hospital, we treated 5.7% of all Slovenian patients with AP, which corresponds to the proportion of the population that is generally seen at our institution. The length of stay in our hospital was significantly lower (P = 0.018) than in the other Slovenian hospitals (Figure 1).

The proportion of patients who died in our hospitals represented 1.9% of all deaths of patients from AP in the country. In Slovenia, 37 patients die per year, which represents 4% of all hospitalised patients with AP.

The leading causes of AP remain gallstones and alcohol consumption, which corresponds to previously published studies. The age difference between patients with AP of alcoholic and biliary genesis raises concern, as it indirectly suggests higher alcohol consumption in the younger population. A useful diagnostic method in everyday clinical practice is carbohydrate deficient transferrin (CDT), which is determined in cases of suspected alcohol abuse and unexplained AP. The high sensitivity (60%-70%) and specificity (80%-90%) of this test provide clinical utility, and these are even higher when the levels of serum gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) and mean corpuscular volume (MCV) are simultaneously elevated[9-12].

After CP implementation, we achieved a significant reduction in the proportion of unexplained AP by regularly determining the routine laboratory tests (CDT, triglycerides) at the first patient examination, and additionally performing endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) of the biliary system in cases of suspected micro-cholelithiasis, thereby increasing the proportion of confirmed alcoholic, hyperlipemic and biliary AP.

Cases of hyperlipemic AP are rare, and such an origin can only be confirmed when all other aetiological causes are excluded and the serum triglycerides level exceeds 11.0 mmol/L[13]. Micro-cholelithiasis (concrements smaller than 5 mm) is a frequent cause of AP in what may initially seem to be unexplained cases and is found in 20%-40% of such patients[14]. Tandon et al[15] confirmed a biliary aetiology in two thirds of the 31 patients with previously diagnosed unexplained AP by performing EUS. There is no consensus regarding the definition of idiopathic AP. We consider it when medical history, extended laboratory testing and radiological examinations (US and CT) do not explain the aetiology of AP[16].

In recurrent unexplained AP in patients 40 years or younger, α-1-antitrypsin, chloride sweat test (to exclude cystic fibrosis), genetic testing (CFTR, SPINK 1, and PRSS1 genes), immunoglobulin G4, the antinuclear antibody (ANA) test, a urine drug test and microscopic duodenal aspirate analysis (in search for microcrystals and micro-cholelithiasis) should be performed, in addition to EUS. In patients over 40 years of age, CA19-9 tumour marker should be assessed[17,18].

The medical literature often describes solitary cases with possible links between certain medications and AP, but the following four requirements need to be fulfilled to confirm such a correlation: the more common causes of AP must be excluded, AP must develop during consumption of the medication, resolve after cessation and repeat at the reintroduction of the medication[19]. Based on the number of published cases, the time from medication exposure to AP development and the patient reaction at medication reintroduction, we could classify all medications into four groups[20]. Medications from the first and the second group have the greatest potential to cause AP. In our patients, we found such a possible link in four cases, specifically, involving trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, liraglutide, ramipril and perindopril. We did not reexpose our patients to the proposed medications, but chose an alternative medication with a similar original clinical effect.

We confirmed smoking in 19 (13.6%) of our patients, but could not confirm the correlation between smoking and the occurrence or severity of AP. In 16 smokers, alcoholic AP was confirmed. Of them, two had tumours and one had unexplained AP. A correlation between smoking and pancreatic cancer has been demonstrated several times[21-23]. In recent years, smoking has also been related to AP[24].

Another positive effect of CP implementation is the reduction of prescribed antibiotics with no significant difference in treatment outcome (death). In our department, the treatment starts with the combination of ciprofloxacin and metronidazole, which is replaced by imipenem in cases of treatment failure. CP implementation was also a success in the area of supportive therapy, as all patients had adequate analgesia and crystalloid infusions. Food was reintroduced as soon as it was clinically possible (preferably per os, with the termination of pain or by nasojejunal probe in severely progressing disease), the vital signs were monitored regularly and in cases of haemodynamic instability, the patients were transferred in ICU. The planed diagnostic imaging was on time in all patients and were as follows: abdomen US within 24 h of admittance, abdomen CT in all cases of suspected necrotising AP (but not within the first 48 h), and ERCP in all cases of biliary aetiology. Good cooperation with the surgeons and short waiting periods for elective surgical procedures in our hospital enabled the rapid final treatment and prevented the recurrence of biliary AP.

Taking into account all IOQ, we also achieved a significantly shorter hospital stay, compared with other Slovenian hospitals, and at the same time, preserved the low mortality[25]. According to the Slovenian National Health Institute (SNHI), Slovenian hospitals treat between 900-1000 patients with AP, which ranks us among the European countries with moderate to high incidence (47/100000) of the disease[26]. A meta-analysis of 49 studies by Banks et al. confirmed the high mortality of patients with AP, which was as follows: overall mortality of 2%-9%; 1%-7% in mild AP and 8%-39% in severe AP[25]. The data collected by the SNHI showed 37 deaths from AP per year in Slovenia[26], giving us a 3.8% mortality rate, which is indicative of the good treatment of AP in Slovenia. CP implementation enabled regular patient follow-up after AP, which was not yet emphasised in our area. Indeed, studies have shown two long-term complications of AP, namely exocrine pancreatic insufficiency and diabetes type 3c. They are more often a consequence of necrotising AP of alcoholic aetiology, although they can also develop in mild AP of non-alcoholic aetiology[27-34]. Regular ambulatory follow-up helped us to identify and properly treat these patients.

During the writing of this manuscript, the updated Atlanta recommendations for diagnostics and new recommendations for treatment of patients with AP were published[8,35] and are currently being taken into account in everyday clinical practice.

In conclusion, CP implementation and regular IOQ have a positive effect on the treatment of patients with AP. Our results support all modern recommendations in the AP treatment process. Institutions in which patients with AP are treated should provide multidisciplinary teams, regular IOQ control with critical re-evaluations and maintain high treatment quality. The treatment of patients with AP in a General Hospital can be of high quality if all of the parameters of the clinical pathway are well controlled.

The authors performed a study on the impact of a clinical pathway (CP) and indicators of quality (IOQ) on the treatment of patients with acute pancreatitis (AP) in a General Hospital. This article presents the results of a three-year period after the introduction of a CP and a comparison with the previous period (2006-2007). Our results show that introduction of a CP and control of IOQ has improved the treatment of patients with AP, as assessed by all of the following observed parameters: reduced length of stay, reduced percentage of unexplained cases and reduced use of antibiotic therapy (without changes in total mortality). All results were better in comparison to other hospitals in Slovenia.

The present study confirmed that the treatment of patients with acute pancreatitis in a General Hospital can be of high quality if all of the parameters of the clinical pathway and indicators of quality are well controlled.

The results of the present study show that introduction of a CP and control of IOQ has improved the treatment of patients with AP, as assessed by all of the following observed parameters: reduced length of stay, reduced percentage of unexplained cases and reduced use of antibiotic therapy (without changes in total mortality).

The treatment of patients in a General Hospital can be of high quality if all of the parameters of the clinical pathway and indicators of quality are well controlled.

AP is the acute inflammation of the pancreas that can extend to the peripancreatic tissue and distant organs. AP is clinically manifested as abdominal pain with elevated pancreatic enzymes.

This is an interesting and valuable multicenter study related to the acute pancreatitis and impact of a clinical pathway.

P- Reviewer: Kaplan M S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Stewart G E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Topazian M, Gorelick FS. Acute pancreatitis. Textbook of gastroenterology, 4th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincot Williams & Wilkins 2003; 2026-2061. |

| 2. | Lankisch PG, Karimi M, Bruns A, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB. Temporal trends in incidence and severity of acute pancreatitis in Lüneburg County, Germany: a population-based study. Pancreatology. 2009;9:420-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Birgisson H, Möller PH, Birgisson S, Thoroddsen A, Asgeirsson KS, Sigurjónsson SV, Magnússon J. Acute pancreatitis: a prospective study of its incidence, aetiology, severity, and mortality in Iceland. Eur J Surg. 2002;168:278-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jaakkola M, Nordback I. Pancreatitis in Finland between 1970 and 1989. Gut. 1993;34:1255-1260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lindkvist B, Appelros S, Manjer J, Borgström A. Trends in incidence of acute pancreatitis in a Swedish population: is there really an increase? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:831-837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Halvorsen FA, Ritland S. Acute pancreatitis in Buskerud County, Norway. Incidence and etiology. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Peery AF, Dellon ES, Lund J, Crockett SD, McGowan CE, Bulsiewicz WJ, Gangarosa LM, Thiny MT, Stizenberg K, Morgan DR. Burden of gastrointestinal disease in the United States: 2012 update. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1179-1187.e1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1355] [Cited by in RCA: 1465] [Article Influence: 112.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Banks PA, Bollen TL, Dervenis C, Gooszen HG, Johnson CD, Sarr MG, Tsiotos GG, Vege SS. Classification of acute pancreatitis--2012: revision of the Atlanta classification and definitions by international consensus. Gut. 2013;62:102-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4932] [Cited by in RCA: 4323] [Article Influence: 360.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (45)] |

| 9. | Bell H, Tallaksen CM, Try K, Haug E. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin and other markers of high alcohol consumption: a study of 502 patients admitted consecutively to a medical department. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:1103-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Yersin B, Nicolet JF, Dercrey H, Burnier M, van Melle G, Pécoud A. Screening for excessive alcohol drinking. Comparative value of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, gamma-glutamyltransferase, and mean corpuscular volume. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1907-1911. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hock B, Schwarz M, Domke I, Grunert VP, Wuertemberger M, Schiemann U, Horster S, Limmer C, Stecker G, Soyka M. Validity of carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (%CDT), gamma-glutamyltransferase (gamma-GT) and mean corpuscular erythrocyte volume (MCV) as biomarkers for chronic alcohol abuse: a study in patients with alcohol dependence and liver disorders of non-alcoholic and alcoholic origin. Addiction. 2005;100:1477-1486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | De Feo TM, Fargion S, Duca L, Mattioli M, Cappellini MD, Sampietro M, Cesana BM, Fiorelli G. Carbohydrate-deficient transferrin, a sensitive marker of chronic alcohol abuse, is highly influenced by body iron. Hepatology. 1999;29:658-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fortson MR, Freedman SN, Webster PD. Clinical assessment of hyperlipidemic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:2134-2139. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Ko CW, Sekijima JH, Lee SP. Biliary sludge. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:301-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tandon M, Topazian M. Endoscopic ultrasound in idiopathic acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:705-709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Coté GA, Imperiale TF, Schmidt SE, Fogel E, Lehman G, McHenry L, Watkins J, Sherman S. Similar efficacies of biliary, with or without pancreatic, sphincterotomy in treatment of idiopathic recurrent acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1502-1509.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Levy MJ, Geenen JE. Idiopathic acute recurrent pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2540-2555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Baillie J. What should be done with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis that remains ‘idiopathic’ after standard investigation? JOP. 2001;2:401-405. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Mallory A, Kern F. Drug-induced pancreatitis: a critical review. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:813-820. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Badalov N, Baradarian R, Iswara K, Li J, Steinberg W, Tenner S. Drug-induced acute pancreatitis: an evidence-based review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:648-661; quiz 644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Yen S, Hsieh CC, MacMahon B. Consumption of alcohol and tobacco and other risk factors for pancreatitis. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116:407-414. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Bourliere M, Barthet M, Berthezene P, Durbec JP, Sarles H. Is tobacco a risk factor for chronic pancreatitis and alcoholic cirrhosis? Gut. 1991;32:1392-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ghadirian P, Lynch HT, Krewski D. Epidemiology of pancreatic cancer: an overview. Cancer Detect Prev. 2003;27:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Lindkvist B, Appelros S, Manjer J, Berglund G, Borgstrom A. A prospective cohort study of smoking in acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2008;8:63-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Banks PA, Freeman ML. Practice guidelines in acute pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2379-2400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1181] [Cited by in RCA: 1149] [Article Influence: 60.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Slovenian Institute of Public Health, online access 2013 April 28. Available from: http://www.ivz.si. |

| 27. | Symersky T, van Hoorn B, Masclee AA. The outcome of a long-term follow-up of pancreatic function after recovery from acute pancreatitis. JOP. 2006;7:447-453. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Boreham B, Ammori BJ. A prospective evaluation of pancreatic exocrine function in patients with acute pancreatitis: correlation with extent of necrosis and pancreatic endocrine insufficiency. Pancreatology. 2003;3:303-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Connor S, Alexakis N, Raraty MG, Ghaneh P, Evans J, Hughes M, Garvey CJ, Sutton R, Neoptolemos JP. Early and late complications after pancreatic necrosectomy. Surgery. 2005;137:499-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 207] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Pezzilli R, Simoni P, Casadei R, Morselli-Labate AM. Exocrine pancreatic function during the early recovery phase of acute pancreatitis. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2009;8:316-319. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Gupta R, Wig JD, Bhasin DK, Singh P, Suri S, Kang M, Rana SS, Rana S. Severe acute pancreatitis: the life after. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1328-1336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Appelros S, Lindgren S, Borgström A. Short and long term outcome of severe acute pancreatitis. Eur J Surg. 2001;167:281-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tsiotos GG, Luque-de León E, Sarr MG. Long-term outcome of necrotizing pancreatitis treated by necrosectomy. Br J Surg. 1998;85:1650-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bozkurt T, Maroske D, Adler G. Exocrine pancreatic function after recovery from necrotizing pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:55-58. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Working Group IAP/APA Acute Pancreatitis Guidelines. IAP/APA evidence-based guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2013;13:e1-e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1080] [Cited by in RCA: 1037] [Article Influence: 86.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |