Published online Aug 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9134

Peer-review started: February 26, 2015

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: April 12, 2015

Accepted: May 7, 2015

Article in press: May 7, 2015

Published online: August 14, 2015

Processing time: 173 Days and 2.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate the predictive factors of self-expandable metallic stent patency after stent placement in patients with inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

METHODS: A total of 116 patients underwent stent placements for inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction at a tertiary academic center. Clinical success was defined as acceptable decompression of the obstructive lesion within the malignant gastroduodenal neoplasm. We evaluated patient comorbidities and clinical statuses using the World Health Organization’s scoring system and categorized patient responses to chemotherapy using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria. We analyzed the relationships between possible predictive factors and stent patency.

RESULTS: Self-expandable metallic stent placement was technically successful in all patients (100%), and the clinical success rate was 84.2%. In a multivariate Cox proportional hazards model, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were correlated with a reduction in stent patency [P = 0.006; adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 2.92, 95%CI: 1.36-6.25]. Palliative chemotherapy was statistically associated with an increase in stent patency (P = 0.009; aHR = 0.27, 95%CI: 0.10-0.72).

CONCLUSION: CEA levels can easily be measured at the time of stent placement and may help clinicians to predict stent patency and determine the appropriate stent procedure.

Core tip: Self-expandable metallic stent placement is an effective palliative treatment in patients who have inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. However, clinical parameters associated with stent patency have been controversial. This retrospective study investigated the potential predictive factors of stent patency. We found that carcinoembryonic antigen level is an easily determined parameter that is associated with stent patency in malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

- Citation: Kim SH, Chun HJ, Yoo IK, Lee JM, Nam SJ, Choi HS, Kim ES, Keum B, Seo YS, Jeen YT, Lee HS, Um SH, Kim CD. Predictors of the patency of self-expandable metallic stents in malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(30): 9134-9141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i30/9134.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9134

Up to 20% of patients with progressive pancreatic or peripancreatic malignancies may experience symptoms caused by gastric outlet obstruction, including nausea, vomiting, dehydration, and poor nutrition, which cause considerable morbidity[1,2]. Surgical gastrojejunostomy has been considered a classic treatment option for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. While surgical gastrojejunostomy offers good functional outcomes and symptom improvements have been noted in 72% of patients[3], it can have high rates of mortality (2%-36%) and morbidity (13%-55%)[4]. Poor outcomes following gastrojejunostomy have been reported in past studies[5,6]. Additionally, this surgical procedure is not appropriate for patients whose physical status prevents them from tolerating surgery.

Recently, self-expandable metallic stent (SEMS) insertion has emerged as an effective and feasible technique for the palliation of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. SEMS insertions can facilitate the rapid resumption of oral intake and shorter hospital stays compared to the hospital stays required for gastrojejunostomies[7-9]. However, complications that include stent migration and tumor overgrowth frequently occur after SEMS placement[4,10], and, although rare, severe complications such as bleeding and perforations can occur. In addition, providing a variety of treatments for gastrointestinal cancer could prolong patient survival for those who have malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Therefore, estimating SEMS patency after it has been inserted is important for determining its effectiveness as a palliative therapy for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. However, few published studies are available that describe the predictive factors of stent patency in patients who have undergone SEMS placements for the palliative treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction[11-13]. Some studies have reported that chemotherapy is a prognostic factor significantly associated with increased stent patency[11,14]. Additionally, malignant obstructive lesions[15,16] and the type of SEMS inserted[17] have been shown to be possible prognostic factors. Controversies remain about these predictive factors, and demand is increasing for simple and effective predictive factors that are associated with stent patency in inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a frequently used tumor marker, and its levels are usually elevated in the serum of patients who have colorectal carcinomas, gastric carcinomas, and pancreatic carcinomas[18]. However, its value in evaluating stent patency has not been fully elucidated.

This study aimed to assess the efficacy of SEMS and to determine possible predictive factors associated with stent patency in the palliative therapy of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

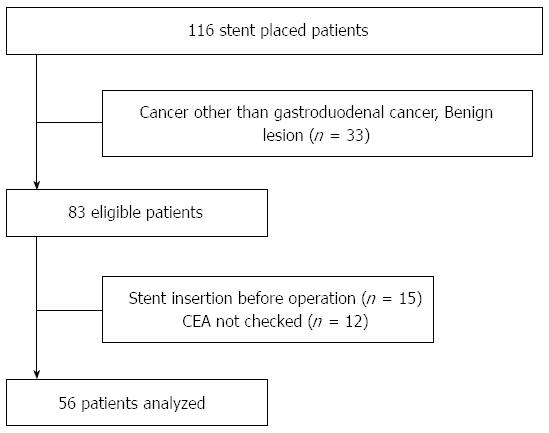

We retrospectively collected data relating to stent placement procedures performed between January 2006 and April 2013. A total of 116 patients underwent stent placements for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction at the Korea University Medical Center, and, of these, 56 patients were enrolled to participate in this study. The inclusion criteria for this study were patients who had inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction and patients who had symptoms caused by gastroduodenal obstruction. The exclusion criteria were patients who had benign strictures, patients who had surgery performed after stent placement, and patients for whom a CEA value was not recorded when the stent was inserted. This study was reviewed and approved ethically by the Korea University Anam Hospital Institutional review board (IRB No. ED13047).

We used Hanarostent SEMS (M. I. Tech, Seoul, South Korea). The stents’ diameters were 18-20 mm and they were 60-160 mm long. Of the 56 stent placements, covered stents were used in 27 patients and uncovered stents were used in the remaining patients. The physician who performed the stent placements decided which stent type to use based on the clinical situation. The size of the stent was chosen based on the approximate dimensions of the stricture, and its length was determined by adding 20 mm to the stricture length on both sides.

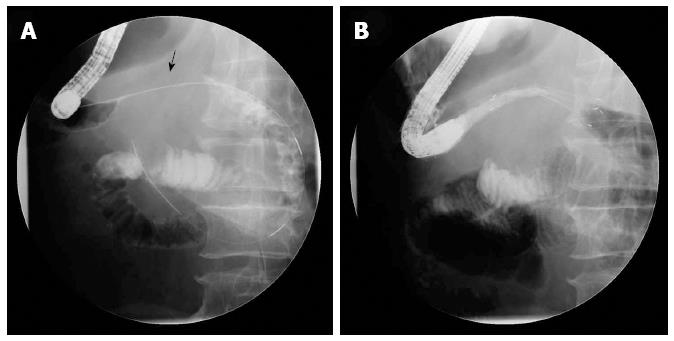

We used a GIF-H260 endoscope (Olympus Optical Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) in this study. An experienced endoscopist successfully inserted all of the stents using a combined endoscopic and fluoroscopic method (Figure 1). The details of the stent deployment procedure used have been described in a previous study[19]. The stent placement procedure was performed while the patients were under standard conscious sedation induced by propofol and/or midazolam and in either the left decubitus position or the prone position. Patients were advised to consume water or a liquid diet on the day of the procedure and a soft diet on the day following the procedure.

The duration of stent patency was defined as the time from stent insertion to the time that stent dysfunction occurred due to tumor ingrowth or stent migration. If no complications that were associated with the stent arose, the duration of stent patency was considered to be identical to the patient’s duration of life or the last day the patient visited the hospital. The technical success of the stent was defined as its successful placement at the site of the obstruction. Clinical success was defined as acceptable decompression of the obstructive lesion within the malignant gastroduodenal neoplasm, and clinical success was confirmed when there were indications that the obstructive symptoms had been relieved; namely, the resumption of oral food intake and the resolution of obstructive signs on abdominal radiographs[20]. The gastric outlet obstruction scoring system (GOOSS) was also used to assess oral dietary intake levels before and after the procedure[21]. We evaluated the patients’ comorbidities and clinical statuses using the World Health Organization’s scoring system[22]. We categorized the patients’ responses to chemotherapy using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors criteria[23]. A responder to chemotherapy was defined as a patient who had a complete response, a partial response or stable disease after chemotherapy, while a non-responder was defined as a patient who had progressive disease after chemotherapy.

We analyzed the relationships between possible predictive factors and stent patency.

The relief of obstructive symptoms was assessed during the follow up period using endoscopy, using abdominal radiography, and from patient interviews. The patients were followed until stent failure or death. The reasons underlying stent failure were categorized as restenosis, migration, stent fracture, or any other reason that interrupted stent patency. Symptoms and signs were monitored during the follow-up period and used to indicate stent failure. When stent failure was suspected, abdominal radiographic and endoscopic evaluations were performed to assess stent patency. The data were obtained from clinical records, endoscopic reports, and radiologic reports.

The independent samples t-test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare the variables. We compared the CEA levels between the study cohorts based on stent dysfunction using the Mann-Whitney U test. The optimal cut-off value of CEA for predicting stent patency was determined using a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The area under the ROC curve and the significance level were analyzed. A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to analyze the significance of the relationship between the possible predictive factors and stent patency in malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Those patients whose follow-up assessments were discontinued were censored. The P values were derived from two-tailed tests, and a P value < 0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics for Windows, Version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Kyung Sook Yang from Department of Biostatistics, Korea University College of Medicine, Seoul, South Korea.

A total of 116 patients underwent stent placements for gastroduodenal obstruction at the Korea University Medical Center between January 2006 and April 2013, and, of these, 83 patients underwent SEMS insertions for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Fifteen patients were excluded from the study because they underwent surgery after stent insertion, and 12 patients (14.5%) were excluded from the study because their CEA level was not measured when the stents were inserted. Consequently, 56 patients were included in the final analyses (Figure 2). None of the patients underwent radiotherapy.

The characteristics of the patients who were included in the final analyses are summarized in Table 1. The patients were admitted to the hospital for a mean duration of 15.7 d. The most common stage of malignancy was Stage IV. Twelve patients started chemotherapy within 2 wk prior to stent insertion, while the remaining patients started chemotherapy within 4 wk after stent insertion. Chemotherapy was not administered to patients who had comorbid conditions or did not wish to receive chemotherapy.

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Mean age, yr (range) | 69 (52-91) |

| Sex (men:women) | 36:20 (64.3:35.7) |

| Chemotherapy | 37 (66.1) |

| Etiology | |

| Gastric cancer | 35 (62.5) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 21 (37.5) |

| Cancer status | |

| Locally advanced | 5 (8.9) |

| Metastasis | 51 (91.1) |

| Stent | |

| Covered | 27 (48.2) |

| Uncovered | 29 (51.8) |

| WHO score | |

| 1 | 49 (12.5) |

| 2 | 7 (87.5) |

| GOOSS score | |

| 0 | 19 (33.9) |

| 1 | 36 (64.2) |

| 2 | 1 (1.8) |

| 3 | 0 (0) |

No acute complications, including perforations or aspiration pneumonia, were noted in patients after stent insertion, and there were no stent insertion-related deaths. SEMS placement was technically successful in all of the patients (100%), and the clinical success rate was 84.2%. We evaluated clinical improvements in the gastric outlet obstruction using the GOOSS score. The GOOSS score was 0.67 before stent insertion and 2.42 after stent insertion. Each of the patients for whom the procedure was clinically successful showed improvements in their post-stent oral consumption.

Stent migration occurred in two patients (3.5%), and stent ingrowth occurred in 13 patients (23.2%). The sources of the malignancies in the patients who experienced stent migration were the stomach (n = 1) and the pancreas (n = 1). Both patients underwent stent placement using covered stents and received chemotherapy after stent insertion. When a stent migrated, it was immediately replaced by another stent.

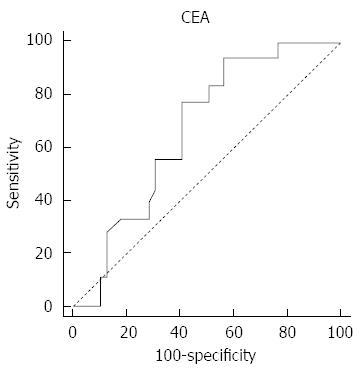

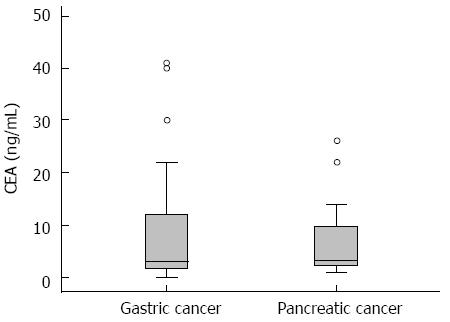

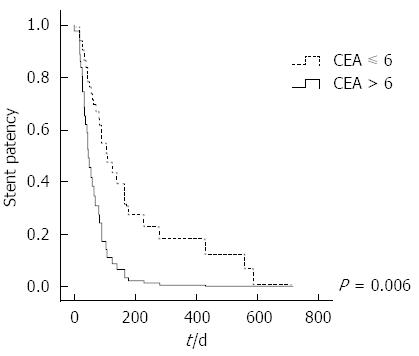

Univariate analysis showed that there was no significant difference in relation to sex, age, the procedural time, the types of obstructive lesion, the stent type, the presence of peritoneal carcinomatosis, and the stage of cancer between the groups that were delineated based on stent dysfunction (Table 2). The mean CEA level was higher in the group that experienced stent failure, but the difference was not statistically significant. ROC analysis, using the duration of stent patency as a classification variable, determined that the cut-off value for CEA was 6 ng/mL (P = 0.019; 95%CI: 0.53-0.78) (Figure 3). The CEA levels were compared in relation to the types of malignancy (Figure 4).

| Stent failure | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 40) | No (n = 16) | ||

| Age (yr) | 67 ± 13.2 | 73.9 ± 12.1 | 0.72 |

| Sex | 0.43 | ||

| Men | 27 (67.5) | 9 (56.2) | |

| Women | 13 (32.5) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Procedure time (min) | 36.4 ± 19.9 | 31.5 ± 18.6 | 0.39 |

| Chemotherapy | 29 (72.5) | 8 (50) | 0.10 |

| Response | 13 (32.5) | 1 (6.3) | 0.09 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 31.1 ± 111.5 | 5.1 ± 5.9 | 0.39 |

| Type of stent | 0.31 | ||

| Covered | 21 (52.5) | 6 (37.5) | |

| Uncovered | 19 (47.5) | 10 (62.5) | |

| Carcinoma peritonei | 14 (35.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.86 |

| Cancer stage1 | 0.47 | ||

| III | 4 (10) | 1 (6.2) | |

| IV | 36 (90) | 15 (93.6) | |

| Gastric cancer | |||

| Chemotherapy | 19 (73.1) | 3 (33.3) | 0.03 |

| Covered stent | 16 (61.5) | 5 (55.6) | 0.75 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 44.6 ± 138.3 | 5.7 ± 6.9 | 0.44 |

| Pancreatic cancer, | |||

| Chemotherapy | 10 (71.4) | 5 (71.4) | 1.00 |

| Covered stent | 5 (35.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0.30 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 7.0 ± 7.1 | 4.4 ± 4.9 | 0.42 |

| CA 19-9 (IU/mL) | 24.597 ± 73.120 | 1.731 ± 2.484 | 0.46 |

| Location of obstruction | 0.57 | ||

| Gastric body | 4 (10) | 1 (6.2) | |

| Pylorus | 22 (55) | 7 (43.8) | |

| Duodenum | 14 (35) | 8 (50) | |

We used Cox proportional hazards models to assess the factors that were anticipated to be associated with stent patency (Table 3). The results indicated that CEA level and chemotherapy were independent predictive factors for the duration of stent patency. When the CEA level was higher than 6 ng/mL at the time of stent placement, stent patency decreased [P = 0.006; adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 2.92, 95%CI: 1.36-6.25] (Figure 5). Palliative chemotherapy was statistically associated with an increase in stent patency (P = 0.009; aHR = 0.27, 95%CI: 0.10-0.72). The chemotherapy response rate was 63.6% in the stent dysfunction group, and 33.3% of the patients died without stent dysfunction. When we analyzed the cohort that underwent chemotherapy separately, a Cox proportional hazards model showed that longer stent patency might be associated with responding to first-line chemotherapy (P = 0.05; aHR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.14-1.02).

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 0.99 | 0.96-1.02 | 0.604 |

| Sex (male) | 2.02 | 0.94-4.30 | 0.068 |

| CEA > 6 ng/mL | 2.92 | 1.36-6.25 | 0.006 |

| WHO score | 3.73 | 1.35-10.31 | 0.011 |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 0.27 | 0.10-0.72 | 0.009 |

| Covered stent | 2.20 | 1.06-4.57 | 0.034 |

| Carcinoma peritonei | 2.64 | 1.16-6.02 | 0.020 |

In recent years, SEMS deployment has progressively replaced surgical gastrojejunostomy for the treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Tringali et al[24] conducted a prospective multicenter study that involved 108 patients with malignant gastroduodenal obstruction who were treated with SEMS and reported a technical success rate of 99.1% and clinical success rate of 87.6%. A meta-analysis of treatment using stents vs surgical gastrojejunostomy published in 2010 by Ly et al[25] showed that endoscopic stenting was associated with an increase in oral intake tolerability, shorter time to the initiation of oral intake, and shorter hospital stays after the procedure.

However, debate remains about what is the most suitable treatment approach for patients who have inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. In general, SEMS deployment is the preferred treatment option for patients who have short life expectancies[26]. However, it is difficult to develop a therapeutic algorithm because the treatment method should be tailored according to disease status and patient preference. Although SEMS deployment is the preferred treatment modality and promptly relieves the symptoms associated with malignant gastroduodenal obstruction, stent-related adverse events may occur[24]. Thus, it is important to be able to predict stent patency within the clinical context of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

There is a growing need to identify factors that can predict stent patency. A few studies that have investigated the factors that may affect SEMS patency following insertion have been published. Telford et al[11] reported that chemotherapy after stent insertion is significantly associated with the prolongation of oral intake (aHR = 0.41, 95%CI: 0.23-0.72). This was the first study to assess the prognostic factors that affect stent patency in the treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion. Since then, other studies[12,14,17] have reported similar results following the use of chemotherapy. In addition to chemotherapy, the stent type and the type of malignant obstructive lesion have been proposed as possible prognostic factors for stent patency[15,17]; however, these results remain controversial. Some studies have reported that chemotherapy has no effect on stent patency in the treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion[15,27,28]. Other studies have reported that stent type and the type of malignant obstructive lesion have no significant associations with stent patency[19,28,29]. Consequently, this is an important subject for further investigation.

Similar to results found in previous studies, this study showed an increase in stent patency in patients who underwent chemotherapy. Performing chemotherapy after stent insertion may reduce or stabilize the tumor burden and diminish tumor growth through the mesh of the stent or overgrowth at the edges of the stent. Kim et al[14] reported first-line chemotherapy to be a significant protective factor against restenosis, which is comparable to our findings.

In addition, the type of malignant obstructive lesion and the type of stent used were not statistically associated with stent patency in our study. Stent migration occurred in two patients who underwent chemotherapy and had covered stents implanted. Previous studies have found that covered stents and undergoing chemotherapy are significant risk factors for stent migration[14,17,19]. The reduction in tumor size caused by chemotherapy could lead to unintentional consequences for patients who receive covered stents because of the increased risk of stent migration.

This study found that peritoneal carcinomatosis and a poor performance status in patients were associated with reductions in stent patency. Documented peritoneal carcinomatosis has been considered a relative contraindication for stent placement[30]. Although another study found that carcinomatosis does not adversely affect stent patency[31], peritoneal seeding should be considered a possible risk for multifocal obstruction. In the same context, the poor performance status of a patient could adversely affect stent patency and could be associated with the systemic effects of the tumor.

In this study, CEA level was found to be a potential novel predictive factor of stent patency in the treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion. CEA is a commonly used tumor marker and has been found to increase in the serum of patients with colorectal carcinomas, gastric carcinomas, pancreatic carcinomas, and other malignancies[18]. CEA level has been shown to be independently associated with prognosis and survival in advanced gastric cancer[32]. In addition, previous studies have demonstrated a significant association between CEA level and the prognosis of advanced pancreatic cancer[33,34]. We performed an analysis that evaluated CEA as a potential predictive factor of stent patency and found that the stent patency rate in patients who had CEA levels > 6 ng/mL was lower than the rate in patients with lower CEA levels. This result suggests that CEA level could be a valuable predictive factor that is independently associated with stent patency in the palliative treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion. CEA level could predict the prognosis of periampullary cancer as well as the patency of stents inserted for the palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. Given that prognostic factors are scarce and no serum markers for stent patency exist, the efficacy of CEA as an easily measurable predictive factor of stent patency that was demonstrated in this study is noteworthy. This study is the first to report CEA as a predictive factor of stent patency in the treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion.

This study has limitations including its single-center, retrospective design and small sample size. However, we investigated sequential patients who had stents inserted for the treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction in our endoscopy unit, and we only enrolled patients who met the inclusion criteria. In addition, the treatment courses were regulated for all patients, which may lessen the limitations associated with the retrospective design of the study.

In conclusion, SEMS placement is an effective palliative treatment in patients who have inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. The level of serum CEA, which can be easily measured, was found to be associated with stent patency in the treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion; thus, CEA level may be an effective predictor of stent patency. After receiving stents, patients with a CEA level > 6 ng/mL could be candidates for short-term follow-up using esophagogastroduodenoscopy within a few months. Through this strategy, physicians could help patients in the determination of appropriate treatment decisions, including, for example, preventing additional stenting before restenosis, and, consequently, they can help reduce patient suffering and re-hospitalization.

Self-expandable metallic stents (SEMS) are used as an effective palliative therapy in inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. However, clinical parameters associated with stent patency have been controversial, and no serum markers currently exist to help determine whether stent insertion may be an appropriate treatment.

It is important to be able to predict stent patency within the clinical context of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. This study assessed the efficacy of SEMS and possible predictive factors of stent patency in the palliative therapy of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction.

The present study showed that carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be a novel predictive factor of stent patency in the palliative treatment of inoperable malignant gastroduodenal obstruction through stent insertion.

The authors could predict the stent prognosis using CEA levels. After performing stent placement, the patients with CEA levels greater than 6 could be candidates for short-term esophagogastroduodenoscopy follow-up.

CEA is a frequently used tumor marker, and its levels are usually elevated in the serum of patients who have colorectal carcinomas, gastric carcinomas, and pancreatic carcinomas.

This is an interesting study, about possible predictors of the patency of self-expandable metallic stents in malignant gastroduodenal obstruction. It is well designed, well written and has an interesting discussion. CEA levels can easily be measured everywhere and this is an useful addition to the treatment of these patients.

P- Reviewer: Cremers MI, Yuksel I S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Pitt HA, Yeo CJ. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322-328; discussion 328-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Maire F, Hammel P, Ponsot P, Aubert A, O’Toole D, Hentic O, Levy P, Ruszniewski P. Long-term outcome of biliary and duodenal stents in palliative treatment of patients with unresectable adenocarcinoma of the head of pancreas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:735-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | van Hooft JE, Dijkgraaf MG, Timmer R, Siersema PD, Fockens P. Independent predictors of survival in patients with incurable malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a multicenter prospective observational study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1217-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, Hof Gv, van Eijck CH, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Gastrojejunostomy versus stent placement in patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction: a comparison in 95 patients. J Surg Oncol. 2007;96:389-396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Weaver DW, Wiencek RG, Bouwman DL, Walt AJ. Gastrojejunostomy: is it helpful for patients with pancreatic cancer? Surgery. 1987;102:608-613. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Fujino Y, Suzuki Y, Kamigaki T, Mitsutsuji M, Kuroda Y. Evaluation of gastroenteric bypass for unresectable pancreatic cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:563-568. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Del Piano M, Ballarè M, Montino F, Todesco A, Orsello M, Magnani C, Garello E. Endoscopy or surgery for malignant GI outlet obstruction? Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:421-426. [PubMed] |

| 8. | van Hooft JE, van Montfoort ML, Jeurnink SM, Bruno MJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Siersema PD, Fockens P. Safety and efficacy of a new non-foreshortening nitinol stent in malignant gastric outlet obstruction (DUONITI study): a prospective, multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2011;43:671-675. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chandrasegaram MD, Eslick GD, Mansfield CO, Liem H, Richardson M, Ahmed S, Cox MR. Endoscopic stenting versus operative gastrojejunostomy for malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:323-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Hooft JE, Uitdehaag MJ, Bruno MJ, Timmer R, Siersema PD, Dijkgraaf MG, Fockens P. Efficacy and safety of the new WallFlex enteral stent in palliative treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (DUOFLEX study): a prospective multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1059-1066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 148] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Telford JJ, Carr-Locke DL, Baron TH, Tringali A, Parsons WG, Gabbrielli A, Costamagna G. Palliation of patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction with the enteral Wallstent: outcomes from a multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:916-920. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Kim JH, Song HY, Shin JH, Choi E, Kim TW, Jung HY, Lee GH, Lee SK, Kim MH, Ryu MH. Metallic stent placement in the palliative treatment of malignant gastroduodenal obstructions: prospective evaluation of results and factors influencing outcome in 213 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:256-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Im JP, Kang JM, Kim SG, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Clinical outcomes and patency of self-expanding metal stents in patients with malignant upper gastrointestinal obstruction. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:938-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim CG, Park SR, Choi IJ, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Park YI, Nam BH, Kim YW. Effect of chemotherapy on the outcome of self-expandable metallic stents in gastric cancer patients with malignant outlet obstruction. Endoscopy. 2012;44:807-812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Canena JM, Lagos AC, Marques IN, Patrocínio SD, Tomé MG, Liberato MA, Romão CM, Coutinho AP, Veiga PM, Neves BC. Oral intake throughout the patients’ lives after palliative metallic stent placement for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a retrospective multicentre study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:747-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dolz C, Vilella À, González Carro P, González Huix F, Espinós JC, Santolaria S, Pérez Roldán F, Figa M, Loras C, Andreu H. Antral localization worsens the efficacy of enteral stents in malignant digestive tumors. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:63-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cho YK, Kim SW, Hur WH, Nam KW, Chang JH, Park JM, Lee IS, Choi MG, Chung IS. Clinical outcomes of self-expandable metal stent and prognostic factors for stent patency in gastric outlet obstruction caused by gastric cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:668-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hammarström S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:67-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 838] [Cited by in RCA: 913] [Article Influence: 35.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kim CG, Choi IJ, Lee JY, Cho SJ, Park SR, Lee JH, Ryu KW, Kim YW, Park YI. Covered versus uncovered self-expandable metallic stents for palliation of malignant pyloric obstruction in gastric cancer patients: a randomized, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:25-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | García-Cano J, González-Huix F, Juzgado D, Igea F, Pérez-Miranda M, López-Rosés L, Rodríguez A, González-Carro P, Yuguero L, Espinós J. Use of self-expanding metal stents to treat malignant colorectal obstruction in general endoscopic practice (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:914-920. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Adler DG, Baron TH. Endoscopic palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction using self-expanding metal stents: experience in 36 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:72-78. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, McFadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649-655. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15860] [Cited by in RCA: 21580] [Article Influence: 1348.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Tringali A, Didden P, Repici A, Spaander M, Bourke MJ, Williams SJ, Spicak J, Drastich P, Mutignani M, Perri V. Endoscopic treatment of malignant gastric and duodenal strictures: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:66-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 25. | Ly J, O’Grady G, Mittal A, Plank L, Windsor JA. A systematic review of methods to palliate malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:290-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Jeurnink SM, Steyerberg EW, van Hooft JE, van Eijck CH, Schwartz MP, Vleggaar FP, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Surgical gastrojejunostomy or endoscopic stent placement for the palliation of malignant gastric outlet obstruction (SUSTENT study): a multicenter randomized trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:490-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 358] [Cited by in RCA: 359] [Article Influence: 23.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Cha BH, Lee SH, Kim JE, Yoo JY, Park YS, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N, Lee DH, Hwang JH. Endoscopic self-expandable metallic stent placement in malignant pyloric or duodenal obstruction: does chemotherapy affect stent patency? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2013;9:162-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Cheng HT, Lee CS, Lin CH, Cheng CL, Tang JH, Tsou YK, Chang JM, Lee MH, Sung KF, Liu NJ. Treatment of malignant gastric outlet obstruction with metallic stents: assessment of whether gastrointestinal position alters efficacy. J Investig Med. 2012;60:1027-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Kim YW, Choi CW, Kang DH, Kim HW, Chung CU, Kim DU, Park SB, Park KT, Kim S, Jeung EJ. A double-layered (comvi) self-expandable metal stent for malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2030-2036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Baron TH, Harewood GC. Enteral self-expandable stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:421-433. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Mendelsohn RB, Gerdes H, Markowitz AJ, DiMaio CJ, Schattner MA. Carcinomatosis is not a contraindication to enteral stenting in selected patients with malignant gastric outlet obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:1135-1140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Liu X, Cai H, Wang Y. Prognostic significance of tumor markers in T4a gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Haas M, Heinemann V, Kullmann F, Laubender RP, Klose C, Bruns CJ, Holdenrieder S, Modest DP, Schulz C, Boeck S. Prognostic value of CA 19-9, CEA, CRP, LDH and bilirubin levels in locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer: results from a multicenter, pooled analysis of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:681-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Lundin J, Roberts PJ, Kuusela P, Haglund C. The prognostic value of preoperative serum levels of CA 19-9 and CEA in patients with pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:515-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |