Published online Jan 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.1044

Peer-review started: June 3, 2014

First decision: June 27, 2014

Revised: July 29, 2014

Accepted: September 18, 2014

Article in press: September 19, 2014

Published online: January 21, 2015

Processing time: 232 Days and 4.8 Hours

Ulcerative colitis in addition to inflammatory polyposis is common. The benign sequel of ulcerative colitis can sometimes mimic colorectal carcinoma. This report describes a rare case of inflammatory polyposis with hundreds of inflammatory polyps in ulcerative colitis which was not easy to distinguish from other polyposis syndromes. A 16-year-old Chinese male suffering from ulcerative colitis for 6 mo underwent colonoscopy, and hundreds of polyps were observed in the sigmoid, causing colonic stenosis. The polyps were restricted to the sigmoid. Although rectal inflammation was detected, no polyps were found in the rectum. A diagnosis of inflammatory polyposis and ulcerative colitis was made. The patient underwent total colectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis. The patient recovered well and was discharged on postoperative day 8. Endoscopic surveillance after surgery is crucial as ulcerative colitis with polyposis is a risk factor for colorectal cancer. Recognition of polyposis requires clinical, endoscopic and histopathologic correlation, and helps with chemoprophylaxis of colorectal cancer, as the drugs used postoperatively for colorectal cancer, ulcerative colitis and polyposis are different.

Core tip: This case report describes ulcerative colitis with inflammatory polyps in a teenage boy. The macropathology of inflammatory polyps excised from the colon was similar to that of familial adenomatous polyps and hyperplastic polyps. In this article, we discuss the difficulties in distinguishing inflammatory polyposis from similar polyps and emphasize the importance of the chemoprophylaxis of colorectal cancer developed from ulcerative colitis and polyps.

- Citation: Feng JS, Ye Y, Guo CC, Luo BT, Zheng XB. Ulcerative colitis with inflammatory polyposis in a teenage boy: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(3): 1044-1048

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i3/1044.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i3.1044

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is one of two major types of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD); the other is Crohn’s disease (CD). The age of onset follows a bimodal pattern, with a major peak at 15-25 years and a smaller peak at 55-65 years, although the disease can occur at any age[1]. Inflammatory polyps are usually found in the setting of severe inflammatory diseases such as IBD, and carcinoma can occur in inflammatory polyps, especially unusual inflammatory polyps in complex formations. Here we present the case of a 16-year-old male with inflammatory polyposis (IP) in addition to UC, and describe its appearance on colonoscopy and gross specimen following surgery. To the best of our knowledge, such a severe condition at such a young age is rare, and it is necessary to distinguish the polyposis in this case from other polyposis syndromes.

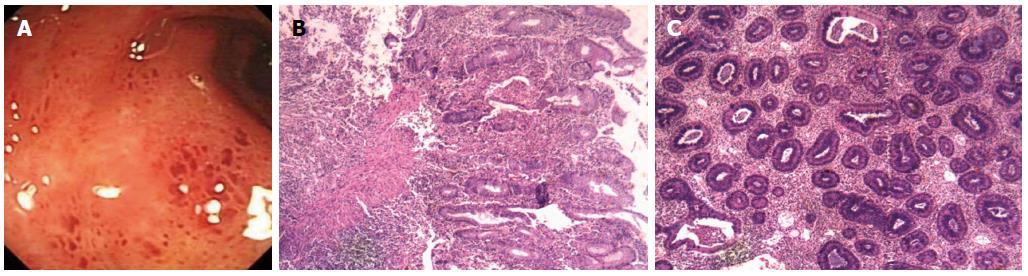

A 16-year-old Chinese male suffering from recurrent abdominal pain and diarrhea with mucosanguineous feces for six months was referred to our department on September 18, 2012. The patient had occasional fever with dark red stool and stench on one or two occasions. He showed no obvious weight loss, had no relevant family history, and did not smoke or drink alcohol. Six months previously he had been diagnosed with UC based on colonoscopy (Figure 1A) and histology of biopsy (Figure 1B, C). At that time, physical examination showed no obvious abdominal abnormality. Laboratory examinations showed C reactive protein (CRP) of 19.0 mg/L, hemoglobin (HGB) of 63 g/L, and platelets (PLT) of 503 × 109/L. The patient received mesalazine for six months, but the symptoms recurred.

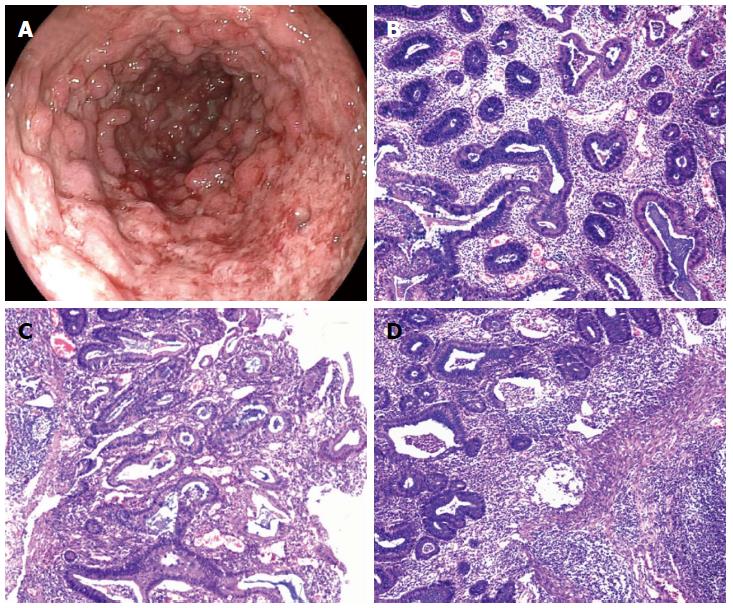

Six months later on September 21, 2012, a second colonoscopy was performed, revealing a large number of polyps in the sigmoid lumen, mucosal swelling, friability, erosions, loss of vascular pattern, and substantial superficial punctate hemorrhage. The large number of polyps had also resulted in stenosis in the sigmoid lumen (Figure 2A). The lens was unable to pass through the stenosis into the enteric cavity. The rectal mucosa showed inflammation and ulcer formation, but no polyps.

The patient underwent a total colectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) on October 7, 2012. Macroscopic examination of the resected colon revealed a large number of diffuse inflammatory polyp-like protrusions (more than a few hundreds) at both ends of the excision. Polyp diameter ranged from 0.3 to 0.8 cm. Histological analysis showed inflammatory polyposis (Figure 2B-D), and no granulomatous, adenomatous or malignant changes were noted. After surgery, the patient’s condition improved and he was discharged on postoperative day 8. Examination was performed six months later, and an increase in stool frequency was observed. The boy’s quality of life was normal, and acute and chronic complications such as bleeding, pelvic abscess, pouchitis, pouch failure, intestinal obstruction, and chronic pelvic infection were not found.

Inflammatory polyps are often found in inflammatory diseases of the colonic mucosa, such as UC in remission, and they may produce symptoms of pain[2] and obstruction[3], especially giant polyps[4]. In this case, the patient developed UC at an early age which was quickly complicated by severe inflammatory polyposis, which is unusual in UC. As seen in the endoscope image, numerous polyps were mainly located in the sigmoid which led to stenosis, and there was no histological evidence of neoplasm or CD which may have resulted in stenosis of the lumen (Figure 2B-D). According to endoscopic and surgical findings, it is necessary to distinguish inflammatory polyposis from other polyposis syndromes.

Another type of polyposis is familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) which is characterized by the presence of hundreds to thousands of adenomatous polyps throughout the colon. The World Health Organization (WHO) diagnostic criteria for FAP are as follows: (1) 100 or more colorectal adenomas or (2) a germline mutation of the APC gene; or (3) a family history of FAP and at least one of the following: epidermoid cysts, osteomas, and desmoid tumor. There appears to be no significant ethnic or racial differences in the incidence of FAP. In this case, the gross findings in the excised specimen were similar to FAP, which confused the diagnosis. The potential relationship between FAP and UC is not clear. A 50-year-old man with no known history or symptoms of IBD presenting with filiform polyposis involving the entire colon, clinically mimicking FAP, and showing histologic features similar to neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of the small bowel was reported[5]. Leal and colleagues found that patients with UC had significantly higher protein levels of Bax, APAF-1, and Caspase-9 than patients with FAP[6]. The average age of onset of polyposis in FAP is 16 years, which was the age of our patient. However, the histologic appearance of the resected specimen did not match the criteria for FAP (Figure 2B-D).

Hyperplastic polyposis (HP) is another type of polyposis. HP is usually diagnosed in individuals in their 40’s to 60’s, although it has been reported in patients as young as 11 years[7]. The syndrome and its inherent risk of malignant disease should be considered when polyps are numerous (more than 20, i.e., polyposis), large (> 1 cm), and proximally located (especially if more than five are proximal to the sigmoid colon), and especially when there are serrated adenomas[8,9]. A family history of HP is uncommon, but colorectal cancer (CRC) in a first-degree relative of a patient with HP is common and reflects inherited increased risk, perhaps associated with the putative heterozygous state[10].

There are similar characteristics in UC, FAP and HP, respectively. Firstly, individuals with these diseases are clearly at increased risk of CRC. FAP is an autosomal-dominant CRC syndrome that can be caused by a germline mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on chromosome 5q21[11]. For patients who inherit the FAP mutation, there is a virtually 100% risk of colon cancer[12,13]. Colon cancer will develop in some patients as early as pre-teenage years[14]. The proportion of FAP patients with CRC who are under 20 years old is 2%-15%[15]. In addition, FAP is associated with an increased risk for the development of other malignancies, such as desmoid tumors, lymphoma, adrenal cancer, gastric cancer and ileal adenomas. A high incidence of duodenal polyps has also been described in FAP patients (79.3%)[16].

Recent studies have proposed that, large right-sided sessile “serrated” hyperplastic polyps are prone to oncogenetic and epigenetic changes leading to genetic instability and neoplasia[17,18]. HP will progress to adenocarcinoma through a “serrated neoplastic pathway” and a B type Raf kinase (BRAF) proto-oncogene mutation[19]. About 30% of CRCs develop through this pathway[20]. However, BRAF mutations were not present in any of the polyps of patients with hyperplastic/serrated polyposis in addition to IBD[21]. These findings suggest the possibility of another pathway related to carcinogenesis in IBD. The genetic abnormalities in HP also include oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, especially abnormalities in KRAS and TGFBR2, and loss of chromosome 1p.

UC is also associated with an increased risk of CRC, depending on age at diagnosis, especially in those less than 15 years of age, and is also dependent on the extent of disease at diagnosis[22]. The risk of CRC in patients with UC is approximately 7%-14% by 25 years of age, and the overall incidence rate of CRC is 1.67 per 1000 patient-year[23]. A recent study showed that the risk of developing CRC in patients with UC has steadily decreased over the last six decades, but the extent and duration of the disease has increased this risk[24]. The available data indicate a similar proportion of CRC in FAP and UC patients[15,22]. Whether patients with FAP in addition to UC have a higher risk of CRC is unknown and requires further investigation.

Secondly, abdominal pain and bloody diarrhea with or without mucus are common symptoms of UC and FAP. For patients with UC in addition to other polyposis, it is possible that the early symptoms of UC masked the symptoms of polyposis, however, in some cases, UC is an initial symptom of polyposis, and vice versa. It was reported that late-onset UC can present as filiform polyposis, although there were no associated diverticula, inflammatory lesions or adenomas on endoscopy and the histology of intervening mucosa was strongly suggestive of UC in remission[25]. Thus, there may be a relationship between FAP and UC which needs to be clarified. Another report suggested a link between IBD and FAP as the offspring of an FAP patient suffered from IBD[26]. In this case, however, none of his family members suffered from IBD or other polyposis syndromes, and his polyps were diagnosed after inflammation was observed.

There are some differences among the three types of lesions mentioned above. UC, HP and FAP are all closely related to CRC, however, the chemoprophylaxis for CRC is important, but is contraindicated in UC and neoplastic polyposis. For CRC and some neoplastic polyposis, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are beneficial, but are harmful in UC. NSAIDs play a role in postponing surgery in patients with mild colonic polyposis, in patients with rectal polyposis after prior colectomy, and as an adjunct to endoscopic surveillance; the use of any NSAID regardless of type is associated with a reduced risk of adenomatous polyps[27]. However, the risk is increased in CD and UC[28] and NSAIDs have been reported to induce irreversible exacerbation of IBD[29,30]. As a chemopreventive agent in CRC, the effectiveness of aspirin in FAP is unclear[31]. Researchers have found that the use of aspirin and COX-2 inhibitors was not associated with HP risk[27]. In UC patients, the use of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) can reduce the risk of CRC[32], however, 5-ASA appears to have no effect on reducing the number or shrinking the size of polyps in the APCMin mouse model of FAP[33].

In conclusion, a teenage boy with UC in addition to polyposis with a possible higher risk of CRC is described. Thus, the recognition of polyps requires the correlation of clinical, endoscopic and histopathologic examinations. It is important to make an accurate diagnosis as the chemoprophylaxis for CRC is contraindicated in patients with neoplastic polyps or pseudopolyps. Endoscopic surveillance is neccessary for patients who have undergone colectomy.

Hundreds of polyps were found at the onset of ulcerative colitis in a teenage boy.

Ulcerative colitis complicated by inflammatory polyps: Large numbers of polyps resulted in stenosis in the sigmoid lumen.

Endoscopic and surgical examinations were required to distinguish inflammatory polyposis from familial adenomatous polyposis and hyperplastic polyposis.

Laboratory diagnosis was ulcerative colitis with inflammatory polyps.

Colonoscopy images showed hundreds of polyps in the sigmoid causing colonic stenosis.

Pathological diagnosis indicated inflammatory changes in the colon.

The patient underwent a total colectomy and ileal pouch anal anastomosis.

There are no uncommon terms in this case report.

Some inflammatory polyposis syndromes are similar to familial adenomatous polyposis and hyperplastic polyposis. These disorders should be carefully distinguished and accurately diagnosed to ensure an appropriate therapeutic regimen.

Inflammatory polyposis is not novel in ulcerative colitis but the review of the literature is sound and complete for this case report.

P- Reviewer: Mao AP, Mulberg AE S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Jang ES, Lee DH, Kim J, Yang HJ, Lee SH, Park YS, Hwang JH, Kim JW, Jeong SH, Kim N. Age as a clinical predictor of relapse after induction therapy in ulcerative colitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:1304-1309. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Jang ES; Meenakshisundaram. Isolated diffuse hyperplastic gastric polyposis: a rare case. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6:1428-1429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adelson JW, deChadarévian JP, Azouz EM, Guttman FM. Giant inflammatory polyposis causing partial obstruction and pain in “healed” ulcerative colitis in an adolescent. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1988;7:135-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maggs JR, Browning LC, Warren BF, Travis SP. Obstructing giant post-inflammatory polyposis in ulcerative colitis: Case report and review of the literature. J Crohns Colitis. 2008;2:170-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Oakley GJ, Schraut WH, Peel R, Krasinskas A. Diffuse filiform polyposis with unique histology mimicking familial adenomatous polyposis in a patient without inflammatory bowel disease. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1821-1824. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Leal RF, Ayrizono Mde L, Milanski M, Fagundes JJ, Moraes JC, Meirelles LR, Velloso LA, Coy CS. Detection of epithelial apoptosis in pelvic ileal pouches for ulcerative colitis and familial adenomatous polyposis. J Transl Med. 2010;8:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Keljo DJ, Weinberg AG, Winick N, Tomlinson G. Rectal cancer in an 11-year-old girl with hyperplastic polyposis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;28:327-332. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Macrae FA, Young GP. Neoplastic and nonneoplastic polyps of the colon and rectum [M]//YAMADA T. Textbook of gastroenterology. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2009;1611-1639. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Lin YC, Chiu HM, Lee YC, Shun CT, Wang HP, Wu MS. Hyperplastic polyps identified during screening endoscopy: reevaluated by histological examinations and genetic alterations. J Formos Med Assoc. 2014;113:417-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Smith RJ, Bryant RG. Metal substitutions incarbonic anhydrase: a halide ion probe study. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1975;66:1281-1286. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Burt R, Neklason DW. Genetic testing for inherited colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1696-1716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Burt RW, Samowitz WS. The adenomatous polyp and the hereditary polyposis syndromes. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1988;17:657-678. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Petersen GM, Slack J, Nakamura Y. Screening guidelines and premorbid diagnosis of familial adenomatous polyposis using linkage. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:1658-1664. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Church JM, McGannon E, Burke C, Clark B. Teenagers with familial adenomatous polyposis: what is their risk for colorectal cancer? Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:887-889. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Vasen HF, Möslein G, Alonso A, Aretz S, Bernstein I, Bertario L, Blanco I, Bülow S, Burn J, Capella G. Guidelines for the clinical management of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Gut. 2008;57:704-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 564] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cordero-Fernández C, Garzón-Benavides M, Pizarro-Moreno A, García-Lozano R, Márquez-Galán JL, López Ruiz T, Sobrino S, Bozada JM, Laguna OB. Gastroduodenal involvement in patients with familial adenomatous polyposis. Prospective study of the nature and evolution of polyps: evaluation of the treatment and surveillance methods applied. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1161-1167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chow E, Lipton L, Lynch E, D’Souza R, Aragona C, Hodgkin L, Brown G, Winship I, Barker M, Buchanan D. Hyperplastic polyposis syndrome: phenotypic presentations and the role of MBD4 and MYH. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:30-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jass JR. Hyperplastic polyps of the colorectum-innocent or guilty? Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:163-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ahn HS, Hong SJ, Kim HK, Yoo HY, Kim HJ, Ko BM, Lee MS. Hyperplastic Polyposis Syndrome Identified with a BRAF Mutation. Gut Liver. 2012;6:280-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dörk T, Dworniczak B, Aulehla-Scholz C, Wieczorek D, Böhm I, Mayerova A, Seydewitz HH, Nieschlag E, Meschede D, Horst J. Distinct spectrum of CFTR gene mutations in congenital absence of vas deferens. Hum Genet. 1997;100:365-377. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Srivastava A, Redston M, Farraye FA, Yantiss RK, Odze RD. Hyperplastic/serrated polyposis in inflammatory bowel disease: a case series of a previously undescribed entity. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:296-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, Adami HO. Ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer. A population-based study. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1228-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1294] [Cited by in RCA: 1198] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Castano-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Has the Risk of Developing Colorectal Cancer in Patients With Ulcerative Colitis Been Overstated? a Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:S251-S251. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Castaño-Milla C, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the declining risk of colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:645-659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Papathanasopoulos AA, Katsanos KH, Tsianos EV. Late-onset ulcerative colitis presenting as filiform polyposis. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:488-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Brignola C, Belloli C, De Simone G, Varesco L, Walger P, Areni A, Calabrese C, Di Febo G, Barbara L. Familial adenomatous polyposis and inflammatory bowel disease associated in two kindreds. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:402-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Murff HJ, Shrubsole MJ, Chen Z, Smalley WE, Chen H, Shyr Y, Ness RM, Zheng W. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and risk of adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4:1799-1807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ananthakrishnan AN, Higuchi LM, Huang ES, Khalili H, Richter JM, Fuchs CS, Chan AT. Aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, and risk for Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:350-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hovde O, Farup PG. NSAID-induced irreversible exacerbation of ulcerative colitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:160-161. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bonner GF. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease associated with use of celecoxib. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1306-1308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kim B, Giardiello FM. Chemoprevention in familial adenomatous polyposis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:607-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and metaanalysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1345-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 426] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ritland SR, Leighton JA, Hirsch RE, Morrow JD, Weaver AL, Gendler SJ. Evaluation of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) for cancer chemoprevention: lack of efficacy against nascent adenomatous polyps in the Apc(Min) mouse. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:855-863. [PubMed] |