Published online Aug 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8974

Peer-review started: December 23, 2014

First decision: March 10, 2015

Revised: April 3, 2015

Accepted: May 21, 2015

Article in press: May 21, 2015

Published online: August 7, 2015

Processing time: 229 Days and 2.8 Hours

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma and is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, which is often preceded by a hiatal hernia. We describe a case of esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in long-segment BE (LSBE) associated with a hiatal hernia that was successfully treated with a laparoscopic transhiatal approach (LTHA) without thoracotomy. The patient was a 42-year-old male who had previously undergone laryngectomy and tracheal separation to avoid repeated aspiration pneumonitis. An ulcerative lesion was found in a hiatal hernia by endoscopy and superficial esophageal cancer was also detected in the lower thoracic esophagus. The histopathological diagnosis of biopsy samples from both lesions was adenocarcinoma. There were difficulties with the thoracic approach because the patient had severe kyphosis and muscular contractures from cerebral palsy. Therefore, we performed subtotal esophagectomy by LTHA without thoracotomy. Using hand-assisted laparoscopic surgery, the esophageal hiatus was divided and carbon dioxide was introduced into the mediastinum. A hernial sac was identified on the cranial side of the right crus of the diaphragm and carefully separated from the surrounding tissues. Abruption of the thoracic esophagus was performed up to the level of the arch of the azygos vein via LTHA. A cervical incision was made in the left side of the permanent tracheal stoma, the cervical esophagus was divided, and gastric tube reconstruction was performed via a posterior mediastinal route. The operative time was 175 min, and there was 61 mL of intra-operative bleeding. A histopathological examination revealed superficial adenocarcinoma in LSBE. Our surgical procedure provided a good surgical view and can be safely applied to patients with a hiatal hernia and kyphosis.

Core tip: This report describes a case of esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in long-segment Barrett's esophagus associated with a hiatal hernia that was successfully treated with a laparoscopic transhiatal approach without thoracotomy. This surgical procedure provided a good surgical view and can be safely applied to patients with a hiatal hernia and kyphosis.

- Citation: Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Konishi H, Kinoshita O, Kosuga T, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Sakakura C, Otsuji E. Laparoscopic transhiatal approach for resection of an adenocarcinoma in long-segment Barrett’s esophagus. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(29): 8974-8980

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i29/8974.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i29.8974

Barrett’s esophagus (BE) is a pathological phenomenon in which the normal squamous epithelium is replaced by a specialized or intestinal columnar epithelium[1]. BE is classified as either short-segment BE (SSBE) or long-segment BE (LSBE) according to the length of the metaplastic changes observed by endoscopic examinations[2]. In some cases, BE is accompanied by esophageal adenocarcinoma[3,4]. On the other hand, a minimally invasive approach for esophageal cancer has recently been suggested to avoid a long hospital stay. In 2009, we started performing esophagectomy with a laparoscopic transhiatal approach (LTHA) on patients with esophageal cancer[5-7]. In this method, carbon dioxide is introduced into the mediastinum from the abdominal side, and middle and lower mediastinal operations can be performed via a transhiatal approach. The main advantage of this method is that it provides a good surgical view of the mediastinum and improves the quality of mediastinal surgery, reducing surgical stress.

We present a case of esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in long-segment Barrett’s esophagus and associated with a hiatal hernia that was successfully treated by applying LTHA.

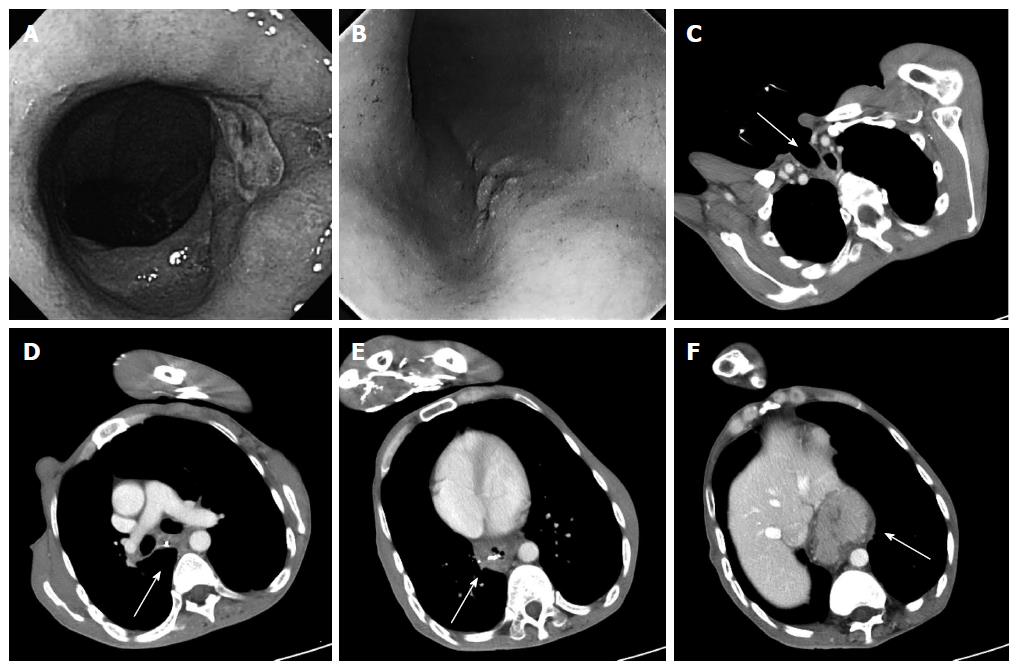

The patient was a 42-year-old man. He had cerebral palsy from birth, and laryngectomy and tracheal separation were performed to avoid repeated aspiration pneumonitis when he was 36 years old. He presented with anorexia, anemia, and black stools. An ulcerative lesion was found by endoscopy in a hiatal hernia 30 cm from an incisor (Figure 1A), and 0-IIc type esophageal cancer was also detected 25 cm from an incisor (Figure 1B)[8,9]. The histopathological diagnosis of biopsy samples from both lesions was adenocarcinoma. Endoscopic marking with metal clips was performed near both lesions. Computed tomography (CT) revealed a sliding hiatal hernia. Metal clips were detected without wall thickening of the esophagus, lymphadenopathy, or metastasis (Figure 1C-F). Because the patient had severe kyphosis and muscular contractures caused by cerebral palsy, there were difficulties with maintaining the left lateral-decubitus position. Furthermore, single lung ventilation from the permanent tracheal stoma appeared to be technically challenging; therefore, a thoracic approach seemed to be unsuitable for him. Instead, we performed subtotal esophagectomy by LTHA without thoracotomy.

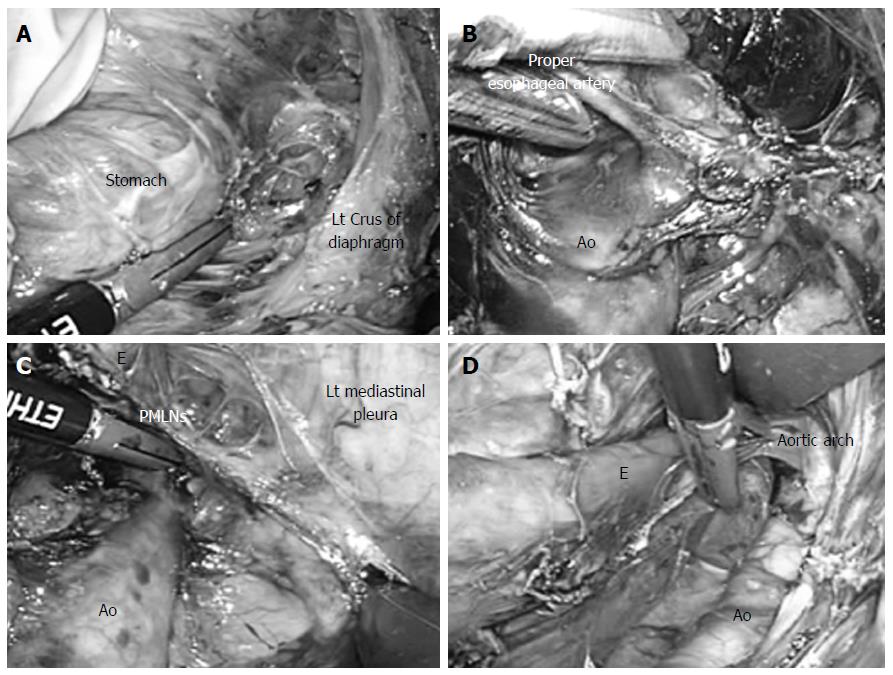

The patient was placed in the supine position on the operating table. An upper abdominal incision (70 mm) was made, and a Lap Disc (regular) (Ethicon, Cincinnati, OH) was placed. Three 12-mm ports were produced, one in each flank and one in the left hypochondrium, and one 5-mm port for a flexible laparoscope was inserted into the lower abdomen, as previously described[5-7]. Carbon dioxide was introduced into the intraabdominal space, and the pneumoperitoneum pressure was controlled at 10 mmHg. The operator lifted up the stomach with the left hand, and the greater omentum, left gastroepiploic vessels, and gastrosplenic ligament were then divided using an EnSeal device (45-cm shaft length, Ethicon). The esophageal hiatus was then opened, and carbon dioxide was introduced into the mediastinum (Figure 2A). The assistant inserted an ENDO RETRACT (Autosuture Norwalk, CT) and blunt tip dissector through the ports on the left side, and the working space in the mediastinum was secured with these two devices and 10 mmHg of pneumomediastinum pressure, as previously described[5-7].

Dissection of the anterior and left side of the distal esophagus was performed up to the level of the tracheal bifurcation. The adventitia of the thoracic aorta was then exposed at the level of the crus of the diaphragm, and we dissected the anterior side of the thoracic aorta to the cranial side. The root of the proper esophageal artery was confirmed (Figure 2B) and divided using the EnSeal device. After these procedures, both the anterior and posterior sides of the posterior mediastinal lymph nodes were dissected. While lifting these lymph nodes like a membrane, we cut them along the border of the left mediastinal pleura (Figure 2C)[6]. This incision was extended to the left pulmonary hilum and aortic arch (Figure 2D).

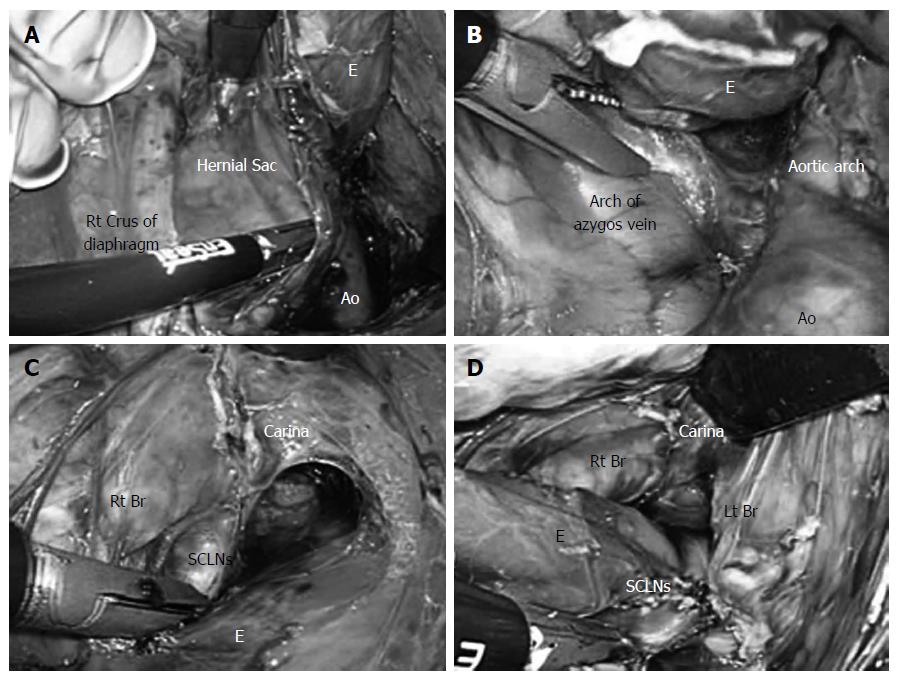

After the left gastric vessels were clipped and divided, the lymph nodes along the left gastric artery were dissected. Dissection of the posterior and right sides of the distal esophagus was finally performed. A hernial sac was identified on the cranial side of the right crus of the diaphragm (Figure 3A). An incision was made in the right mediastinal pleura and extended to the lower margin of the arch of the azygos vein (Figure 3B). As the left side, while lifting the right mediastinal pleura like a membrane, an incision was made and extended to the right pulmonary hilum. The lymph nodes were resected from the right main bronchus and carina (Figure 3C). In this manner, the subcarinal lymph nodes were dissected (Figure 3D)[7]. In this way, the thoracic esophagus was completely detached from the surrounding tissue.

A cervical incision was made in the left side of the permanent tracheal stoma. Cervical and upper mediastinal lymph node dissection was performed. After the cervical esophagus was divided, the esophagus was extracted from the abdominal side. After a gastric tube was created, it was pulled up via a posterior mediastinal route, and esophagogastric anastomosis was performed by hand from a cervical approach.

The operative time was 175 min, and there was 61 mL of intra-operative bleeding.

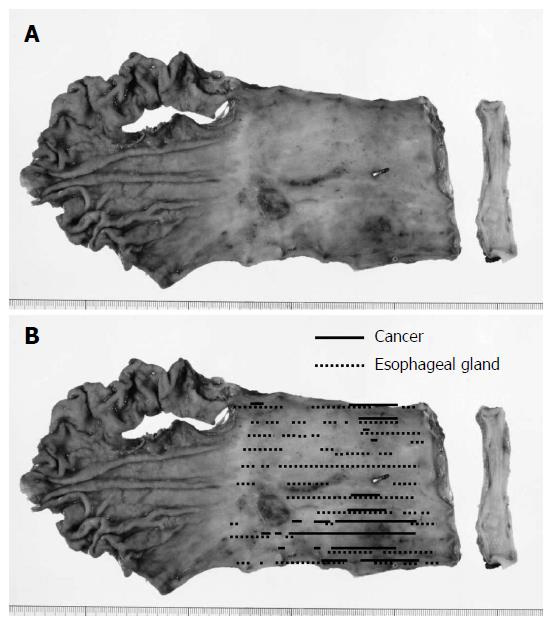

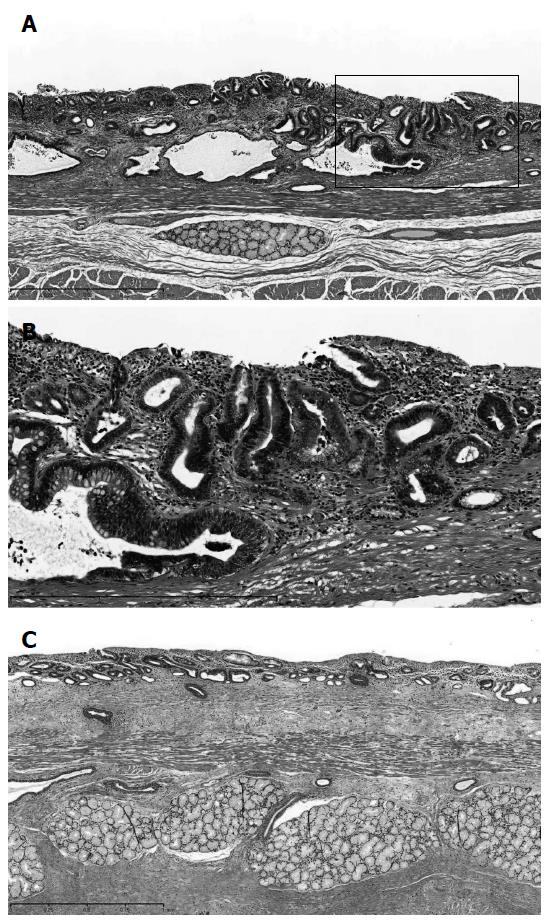

A minor anastomotic leakage was detected on the 11th day after surgery. This leakage healed by drainage treatment. The patient was discharged 51 days after the operation. Gross and histopathological examinations revealed 0-IIc type superficial adenocarcinoma (tub1 >> tub2, 72 mm × 56 mm in size, pT1a-SMM, and no lymph node metastases) of the middle and lower thoracic esophagus in LSBE (Figures 4 and 5)[8,9]. The cancer lesion was surrounded by mucosa, including a columnar epithelium that continued to the stomach (Figure 5A and B). Duplication of the muscularis mucosae was identified (Figure 5C). Although an Ul-IVs type ulcer (17 mm × 17 mm in size) was identified on the distal side of the tumor, cancer was not found in this ulcerative lesion (Figure 4B).

BE is commonly defined as replacement of the esophageal squamous epithelium in the lower esophagus with a metaplastic simple columnar epithelium[1]. BE is associated with the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and the reported prevalence of BE is between 3% and 15% among patients with GERD[10,11]. The clinical significance of BE is its association with an increased risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma[3], and patients with LSBE are at the highest risk of malignancy[4].

The presence of a hiatal hernia has also been associated with an increased risk of BE. The most common type is Type I, or sliding hernia, in which the lower esophageal sphincter and a portion of the gastric cardia herniate upwards due to a widening of the muscular hiatal aperture and circumferential laxity of the phrenoesophageal membrane[12,13]. The presence of a hiatal hernia results in an anatomical impairment in the esophagogastric junction, which results in reflux of gastric material into the esophagus. Individual studies have shown a higher prevalence of hiatal hernia in BE patients than in non-BE GERD patients[14,15]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis revealed that the strongest relationship is between hiatal hernia and LSBE[16]. In addition, the short esophagus is most commonly from the chronic inflammation that accompanies long-standing GERD[17]. The frequency of short esophagus was previously estimated as approximately 10% of patients undergoing antireflux surgery[18]. In the present case, esophageal adenocarcinoma was identified in LSBE. Although short esophagus could not be diagnosed preoperatively because of difficulties associated with upper gastrointestinal radiography, the presence of a hiatal hernia and short esophagus were considered to be associated with pathogenesis.

In the present case, we encountered several difficulties when selecting the appropriate surgical approach. In this case, thoracic procedures performed via right thoracotomy would likely be difficult because of severe kyphosis. Furthermore, single lung ventilation from the permanent tracheal stoma also appeared to be technically challenging. Therefore, we decided to perform subtotal esophagectomy by LTHA without thoracotomy. In addition, the permanent tracheal stoma restricted the selection of a reconstruction route. The presence of the permanent tracheal stoma made it difficult to use a subcutaneous or anterior mediastinal route. Therefore, we used a posterior mediastinal route in the present case.

In 2009, we started performing subtotal esophagectomy by LTHA on patients with esophageal cancer[5-7]. By November 2014, 182 patients with esophageal cancer had undergone LTHA during various esophageal surgical procedures. Our procedure has facilitated middle and lower mediastinal lymph node dissection via a transhiatal approach[6,7]. Because upper mediastinal lymph nodes can be dissected from a cervical approach, we do not perform thoracic surgery in preoperative high-risk patients, including the present case, to reduce surgical invasiveness[7]. The present results suggest that our surgical procedure, esophagectomy by LTHA without thoracotomy, can be safely applied in patients with a hiatal hernia, short esophagus, and severe kyphosis.

In conclusion, we described a case of esophageal adenocarcinoma arising in LSBE associated with a hiatal hernia that was successfully treated using LTHA. Our surgical procedure provides a good surgical view, improves the quality of mediastinal surgery, reduces surgical stress, and can be safely applied to patients with a hiatal hernia and kyphosis.

A 42-year-old male with a history of tracheal separation to avoid repeated aspiration pneumonitis presented with anorexia, anemia, and black stools.

An ulcerative lesion was found in a hiatal hernia by endoscopy, and superficial esophageal cancer was also detected in the lower thoracic esophagus.

Malignant tumor (adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma) and benign disorder (ulcer, hiatal hernia and Barrett’s esophagus).

The patient had no remarkable findings for the laboratory tests or tumor markers (SCC, CEA, CA19-9 and Cyfra).

A computed tomography scan showed a sliding hiatal hernia without wall thickening of the esophagus, lymphadenopathy, or metastasis.

The histopathological diagnosis of biopsy samples from both an ulcer lesion and superficial esophageal cancer was adenocarcinoma.

Subtotal esophagectomy by a laparoscopic transhiatal approach without thoracotomy was performed, and a histopathological examination revealed superficial adenocarcinoma in long-segment Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus is a precursor of esophageal adenocarcinoma and is associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease, which is often preceded by a hiatal hernia.

In the laparoscopic transhiatal approach method, carbon dioxide is introduced into the mediastinum from the abdominal side, and middle and lower mediastinal operations can be performed via a transhiatal approach.

This surgical procedure provided a good surgical view and can be safely applied to patients with a hiatal hernia and kyphosis.

In this article, the authors reported on a patient who was successfully treated by a laparoscopic transhiatal approach. The authors’ actions were novel and commendable when they encountered several difficulties in selecting the surgical approach.

P- Reviewer: Shi Y S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Spechler SJ. Clinical practice. Barrett’s Esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:836-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 387] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sharma P, Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Short segment Barrett’s esophagus--the need for standardization of the definition and of endoscopic criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1033-1036. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Miyazaki T, Inose T, Tanaka N, Yokobori T, Suzuki S, Ozawa D, Sohda M, Nakajima M, Fukuchi M, Kato H. Management of Barrett’s esophageal carcinoma. Surg Today. 2013;43:353-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sikkema M, Looman CW, Steyerberg EW, Kerkhof M, Kastelein F, van Dekken H, van Vuuren AJ, Bode WA, van der Valk H, Ouwendijk RJ. Predictors for neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett’s Esophagus: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1231-1238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Ochiai T. Perioperative outcomes of esophagectomy preceded by the laparoscopic transhiatal approach for esophageal cancer. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27:470-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Nakanishi M, Ichikawa D, Okamoto K, Ochiai T. Posterior mediastinal lymph node dissection using the pneumomediastinum method for esophageal cancer. Esophagus. 2012;9:58-64. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shiozaki A, Fujiwara H, Konishi H, Morimura R, Murayama Y, Komatsu S, Kuriu Y, Ikoma H, Kubota T, Nakanishi M. Novel technique for dissection of subcarinal and main bronchial lymph nodes using a laparoscopic transhiatal approach for esophageal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:2577-2585. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Japan Esophageal Society. Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, tenth edition: part I. Esophagus. 2009;6:1-25. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Japan Esophageal Society. Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, tenth edition: part II and III. Esophagus. 2009;6:71-94. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cameron AJ. Epidemiology of columnar-lined esophagus and adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1997;26:487-494. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Hirota WK, Loughney TM, Lazas DJ, Maydonovitch CL, Rholl V, Wong RK. Specialized intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia, and cancer of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction: prevalence and clinical data. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:277-285. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Buttar NS, Falk GW. Pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux and Barrett esophagus. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76:226-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Gordon C, Kang JY, Neild PJ, Maxwell JD. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:719-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Cameron AJ. Barrett’s esophagus: prevalence and size of hiatal hernia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2054-2059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Avidan B, Sonnenberg A, Schnell TG, Sontag SJ. Hiatal hernia and acid reflux frequency predict presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:256-264. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Andrici J, Tio M, Cox MR, Eslick GD. Hiatal hernia and the risk of Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:415-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Awad ZT, Filipi CJ, Mittal SK, Roth TA, Marsh RE, Shiino Y, Tomonaga T. Left side thoracoscopically assisted gastroplasty: a new technique for managing the shortened esophagus. Surg Endosc. 2000;14:508-512. [PubMed] |