Published online Jun 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7553

Peer-review started: September 10, 2014

First decision: October 14, 2014

Revised: December 2, 2014

Accepted: January 8, 2015

Article in press: January 8, 2015

Published online: June 28, 2015

Processing time: 292 Days and 22.1 Hours

AIM: To investigate whether performing immunohistochemical CD3 staining, in order to improve the detection of intra-epithelial lymphocytosis, has an additional value in the histological diagnosis of celiac disease.

METHODS: Biopsies obtained from 159 children were stained by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and evaluated using the Marsh classification. CD3 staining was subsequently evaluated separately and independently.

RESULTS: Differences in evaluation between the routine HE sections and CD3 staining were present in 20 (12.6%) cases. In 10 (6.3%) patients the diagnosis of celiac disease (Marsh II and III) changed on examination of CD3 staining: in 9 cases, celiac disease had initially been missed on the HE sections, while 1 patient had been over-diagnosed on the routine sections. In all patients, the final diagnosis based on CD3 staining, was concordant with serological results, which was not found previously. In the other 10 (12.3%) patients, the detection of sole intra-epithelial lymphocytosis (Marsh I) improved. Nine patients were found to have Marsh I on CD3 sections, which had been missed on routine sections. Interestingly, the only patient with negative serology had Giardiasis. Finally, in 1 patient with negative serology, in whom Marsh I was suspected on HE sections, this diagnosis was withdrawn after evaluation of the CD3 sections.

CONCLUSION: Staining for CD3 has an additional value in the histological detection of celiac disease lesions, and CD3 staining should be performed when there is a discrepancy between serology and the diagnosis made on HE sections.

Core tip: Intra-epithelial lymphocytosis is considered to be the most important histological finding in celiac disease and therefore provides the key to a correct diagnosis. However, when evaluating the number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes on hematoxylin and eosin stained sections, the lack of contrast between the cells might cause diagnostic difficulties. In this study, we showed that performing CD3 staining improves the histological diagnosis of celiac disease. In fact, this study demonstrated that CD3 staining should be performed when there is a discrepancy between serology and the histological evaluation on routine sections.

- Citation: Mubarak A, Wolters VM, Houwen RH, ten Kate FJ. Immunohistochemical CD3 staining detects additional patients with celiac disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(24): 7553-7557

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i24/7553.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i24.7553

Celiac disease is a permanent intolerance to gluten, a storage protein in wheat and the related grain species barley and rye[1]. Ingesting these grain species in genetically susceptible individuals causes inflammation of the small intestine, which is reversible upon elimination of gluten from the diet[2,3]. To screen for celiac disease, highly specific and sensitive antibodies are available, but until now in many cases a small intestinal biopsy is required for the diagnosis[4,5].

Typically, the triad of an increased density of intra-epithelial lymphocytes (IELs), hyperplasia of the crypts and villous atrophy are observed in patients with celiac disease[2]. However, villous atrophy can also be found in various other diseases such as Giardiasis, Whipple’s disease, Tropical Sprue etc[6]. On the other hand, according to most recent guidelines, villous atrophy is not necessary for the diagnosis of celiac disease, provided that intra-epithelial lymphocytosis and crypt hyperplasia are present[5]. Crypt hyperplasia is a sign of increased intestinal turnover, and is thought to occur secondary to villous destruction and inflammation. The presence of intra-epithelial lymphocytosis, although not pathognomonic for the disease, is considered to be the most important histological finding for celiac disease[7,8]. Therefore, in many cases detecting IELs provides the key to a correct diagnosis. The presence of IELs is usually evaluated on hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained samples, but due to the lack of contrast between the cells, the presence of intra-epithelial lymphocytosis may not always be clear, especially when the number of IELs is only moderately increased. Because IELs are CD3 positive cells, performing immunohistochemical staining against CD3 might aid in estimating the number of IELs. The aim of this study was therefore to investigate whether CD3 staining should be performed routinely on all biopsies, or if it is only necessary in specific cases.

Pediatric patients (53 girls; 106 boys) suspected of having celiac disease who had undergone a small intestinal biopsy between March 2009 and October 2012 in the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, Utrecht, The Netherlands, were prospectively included in the study. Patients were referred to us due to celiac disease-associated symptoms or because they carried a risk factor for celiac disease. All patients carried the disease associated HLA type. Patients were between 0.9 years and 17.8 years old at the time of the biopsy. When a patient had undergone more than one biopsy session, only biopsies from the first session were included in the study.

The results of anti-endomysium antibodies (EMA) and anti-tissue transglutaminase antibodies (tTGA) as well as the clinical data of the patients were collected from their medical records. The study was performed according to the guidelines of the local medical ethical board.

Biopsies were obtained by upper endoscopy. Pediatric gastroenterologists were asked to take at least 4 biopsies from the distal duodenum and as of the end of 2009 at least 1 biopsy from the duodenal bulb. In reality, 0 (in 33 cases) to 5 biopsies were obtained from the duodenal bulb with an average of 2.0 biopsies. From the distal duodenum, 3.1 (range 1-7) biopsies were acquired on average. Biopsies were fixed in formalin (10% neutral buffered formalin) and then embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm-thick sections were stained with HE, Periodic acid-Schiff and CD3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark; batch number 81639; dilution 1:50; pretreatment with EDTA).

All biopsies were evaluated by an experienced pathologist, specialized in gastro-intestinal diseases, who was blinded to the clinical and serological data of the patients. The pathologist first evaluated the HE stained sections. On a separate occasion the CD3 stains were evaluated independently from the HE stains.

Biopsy results were reported according to the Marsh classification, as modified by Oberhuber[2,9]. In case of patchy lesions, the final Marsh score was based on the worst affected site. Marsh I lesions are defined as an increased number of IELs. On the HE-stains this was determined by visual estimation. On the CD3 stains, ≥ 30 lymphocytes per 100 epithelial cells were considered as intra-epithelial lymphocytosis[10,11]. In Marsh II lesions, crypt hyperplasia and an increased number of IELs are found. Finally, Marsh III lesions include the findings in Marsh II, along with various grades of villous atrophy.

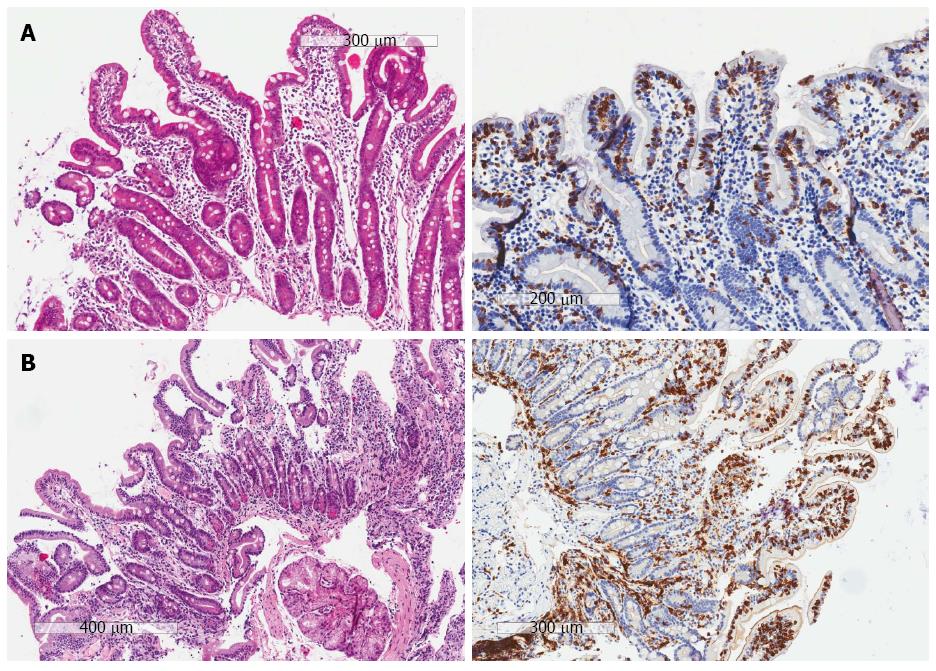

Marsh II and Marsh III lesions were considered to be diagnostic for celiac disease, but were reported separately. Marsh I was reported as a separate entity. Celiac disease was excluded in patients with a normal small intestine (Marsh 0) or abnormalities not diagnostic for Marsh II or III (i.e., only crypt hyperplasia and/or villous atrophy without intra-epithelial lymphocytosis). In the case of discrepancy between the HE and CD3 sections, the final diagnosis was based on the serological data of the patients. For example, a patient with positive serology who has crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy, but increased IEls only on the CD3 sections (no diagnosis of celiac disease on the HE sections, but a Marsh III lesion on the CD3 sections), was considered to have celiac disease (Figure 1A). Similarly, in patients with positive serology and a Marsh 0 on the HE section, but a Marsh I on the CD3 sections, the final diagnosis was considered to be Marsh 1 (Figure 1B).

Descriptive statistics using SPSS for Windows version 15.0 was used to compare the conclusion of the pathologist before and after performing CD3 staining.

A diagnosis of Marsh III, based on the HE stains, was made in 87 patients, but celiac disease was rejected in 1 (1.1%) patient with negative celiac disease serology after examination of the CD3 stains (Table 1). Only 1 patient had a Marsh II lesion on the HE sections which was also identified on the CD3 stains.

| Evaluation of the stains | Evaluation of CD3 stains | |||

| Positive1 | Negative | |||

| Marsh III | Marsh II | Marsh I | No CD | |

| (n = 93) | (n = 3) | (n = 13) | (n = 50) | |

| Marsh III (n = 87) | 86 (98.9) | - | - | 1 (1.1) |

| Marsh II (n = 1) | - | 1 (100) | - | - |

| Marsh I (n = 6) | 1 (16.7) | - | 4 (66.7) | 1 (16.7) |

| No CD (n = 65) | 6 (9.2) | 2 (3.1) | 9 (13.8) | 48 (73.8) |

On the HE stains, 6 patients were considered to have a Marsh I lesion, but in 2 patients the diagnosis of Marsh I changed after assessment of the CD3 stains. In 1 (16.7%) patient with negative celiac disease serology, a Marsh 0 was seen instead and in the other patient (16.7%) a Marsh III lesion was present. In the latter patient, who had positive tTGA and EMA, this could be explained by the fact that on the HE sections a Marsh I lesion was found in the bulb and both crypt hyperplasia and villous atrophy (but without intra-epithelial lymphocytosis) were found in the distal duodenum. Thus, on the HE stains the most affected site seemed to be the duodenal bulb. However, on the CD3 stains an increased number of IELs was seen in both parts of the duodenum, while the most affected site on the CD3 stains was the distal duodenum (Marsh III).

Celiac disease was excluded in 65 patients on the HE slides. However, celiac disease was diagnosed after examining CD3 stains in 6 (9.2%) patients with Marsh III and in 2 (3.1%) patients with Marsh II histology. All of these patients had positive celiac disease serology. Finally, after evaluation of the CD3 stains, Marsh I lesions were identified in another 9 (13.8%) patients. Eight of these patients had positive celiac disease antibodies, whereas 1 patient was negative for tTGA and EMA. Interestingly, the patient with negative serology and Marsh I had Giardiasis.

In summary, differences in the assessment between the HE slides and the CD3 sections were found in 20 (12.6%) patients. In 9 (5.7%) patients, a Marsh I was found and in 1 (0.6%) patient a Marsh I was rejected when the CD3 sections were evaluated. Most importantly, in 10 (6.3%) patients the diagnosis of celiac disease (Marsh II and Marsh III) changed: on the CD3 stains, 1 (0.6%) patient did not have celiac disease, 2 (1.3%) patients had Marsh II lesions and 7 (4.4%) patients had Marsh III histology.

Even after a recent update of the ESPGHAN guidelines for the diagnosis of celiac disease, which states that a biopsy can be omitted in symptomatic cases with very high tTGA levels, positive EMA and the disease-related human leukocyte antigen types, for most patients histological assessment of duodenal biopsies is still necessary for the diagnosis. In this respect, apart from grading villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia, the assessment of intra-epithelial lymphocytosis is essential[5]. We determined whether performing CD3 staining improves the histological evaluation of celiac disease.

Our results show that compared to HE stains alone, CD3 stains did lead to different assessments in 12.6% (20/159) of patients. More importantly, almost 10% (9/96) of patients with celiac disease (Marsh II and III) in the current study would have been missed if CD3 staining had not been performed. It is highly unlikely that these patients were over-diagnosed as all of them had positive celiac disease serology. They probably would not have started a gluten-free diet or would have had subsequent unnecessary biopsies. On the other hand, when the diagnosis of celiac disease is already made on HE slides, the chance that celiac disease will be ruled out on subsequent CD3 stains is small. Yet, without CD3 staining 1 of 48 patients with apparent celiac disease on the HE stains would have been misdiagnosed with the disease, and would therefore unnecessarily have carried the burden of following a gluten-free diet. Interestingly, in this over-diagnosed patient, celiac disease serology was negative. Therefore, in order to identify all Marsh II and Marsh III lesions, and at the same time not over-diagnose any patient with celiac disease, CD3 staining should be performed in all cases of villous atrophy and/or crypt hyperplasia, when the initial conclusion made on the HE stains is discrepant with the serology results.

In addition, performing CD3 staining also led to improved detection of Marsh I lesions. In fact, in almost 14% (9/65) of patients in whom celiac disease was excluded on the HE slides, a Marsh I lesion was found. Interestingly, only 1 of these 9 patients had negative serology, but Marsh I in this patient could be explained by Giardiasis. In addition, without CD3 staining, another patient with negative serology would have been over-diagnosed with Marsh I. Therefore, in order to identify all Marsh I lesions, which are unexplained by other conditions, and at the same time not over-diagnose any patient with Marsh I, CD3 staining should again be performed when there is discrepancy between serology and histology.

The implication of finding lymphocytic enteritis (Marsh I) is unclear, as this lesion does not occur exclusively in celiac disease, and was also seen in our patient with Giardiasis[5,12,13]. Nevertheless, there is some evidence that a Marsh I lesion is clinically important and should therefore be detected, especially in patients with positive serology. Marsh I abnormalities may be an early stage of celiac disease and may thus develop into active celiac disease over time in some patients[14-21]. In addition, a gluten challenge seems to cause mucosal deterioration and a diagnosis of celiac disease in some patients with Marsh I[22]. Finally, various studies have shown that patients with Marsh I lesions might benefit from a gluten-free diet, at least in the short term[17-21].

In conclusion, immunohistochemical staining for CD3 has an additional role in the histological detection of celiac disease lesions. In order to make an appropriate diagnosis of the total spectrum of celiac disease-associated lesions, CD3 staining should be performed in all cases of discrepancy between serology and histology findings on routine sections.

Histological lesions in celiac disease are characterized by intra-epithelial lymphocytosis, crypt hyperplasia and in many cases villous atrophy (Marsh II and III). In addition, the existence of intra-epithelial lymphocytosis only (Marsh I), is also associated with (the development of) the disease. The presence of these lymphocytes in the epithelium is usually evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin (HE) staining, but the lack of contrast between the cells can make evaluation difficult, which can hinder a correct diagnosis. Because intra-epithelial lymphocytes are CD3 positive cells, performing immunohistochemical staining against CD3 might aid in estimating the number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes.

The additional value of performing CD3 staining in the diagnosis of celiac disease has not been studied previously. Therefore, in this study we prospectively compared the results of HE sections to the results of CD3 sections in pediatric patients suspected of having celiac disease. In the case of discrepancy between the two sections, the final diagnosis was based on the clinical and serological data of the patient.

Performing CD3 staining led to an additional diagnosis of Marsh I in 5% of the studied patients, and in 0.6% of the patients the diagnosis was withdrawn after assessment of CD3 stains. More importantly, in 5.7% of patients the diagnosis of celiac disease was missed on routine sections, but was detected by the addition of CD3 staining. Finally, in 0.6% of cases the diagnosis of celiac disease was rejected after evaluation of the CD3 sections.

In order to make an appropriate diagnosis of the total spectrum of celiac disease-associated lesions, CD3 staining should be performed in all cases of discrepancy between serology and histology on routine sections.

Intra-epithelial lymphocytes: CD3 positive lymphocytes present in the small intestine epithelium. An increased number of intra-epithelial lymphocytes is mandatory for the diagnosis of celiac disease. In addition, these lymphocytes are thought to play an important role in the pathophysiology of the disease.

Mubarak et al have assessed the diagnostic improvement of celiac disease by adding immunohistochemical CD3 staining for duodenal mucosal biopsy samples.

P- Reviewer: Nejad MR, Nomura S S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Mäki M, Collin P. Coeliac disease. Lancet. 1997;349:1755-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Marsh MN. Gluten, major histocompatibility complex, and the small intestine. A molecular and immunobiologic approach to the spectrum of gluten sensitivity (‘celiac sprue’). Gastroenterology. 1992;102:330-354. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Grefte JM, Bouman JG, Grond J, Jansen W, Kleibeuker JH. Slow and incomplete histological and functional recovery in adult gluten sensitive enteropathy. J Clin Pathol. 1988;41:886-891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, Saloojee N, Sy R, Garritty C, Sampson M, Zhang L, Yazdi F, Mamaladze V. The diagnostic accuracy of serologic tests for celiac disease: a systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:S38-S46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 333] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Husby S, Koletzko S, Korponay-Szabó IR, Mearin ML, Phillips A, Shamir R, Troncone R, Giersiepen K, Branski D, Catassi C. European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition guidelines for the diagnosis of coeliac disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;54:136-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1708] [Cited by in RCA: 1838] [Article Influence: 141.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 6. | O’Mahony S, Howdle PD, Losowsky MS. Review article: management of patients with non-responsive coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1996;10:671-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oberhuber G, Granditsch G, Vogelsang H. The histopathology of coeliac disease: time for a standardized report scheme for pathologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999;11:1185-1194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1142] [Cited by in RCA: 1205] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Marsh MN, Loft DE, Garner VG, Gordon D. Time/dose responses of celiac mucosae to graded oral challenges with Frazer’s fraction III of gliadin. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1992;4:667-673. |

| 9. | Oberhuber G. Histopathology of celiac disease. Biomed Pharmacother. 2000;54:368-372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | United European Gastroenterology. When is a coeliac a coeliac? Report of a working group of the United European Gastroenterology Week in Amsterdam, 2001. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13:1123-1128. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Veress B, Franzén L, Bodin L, Borch K. Duodenal intraepithelial lymphocyte-count revisited. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:138-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Collin P, Wahab PJ, Murray JA. Intraepithelial lymphocytes and coeliac disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:341-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kakar S, Nehra V, Murray JA, Dayharsh GA, Burgart LJ. Significance of intraepithelial lymphocytosis in small bowel biopsy samples with normal mucosal architecture. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2027-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Salmi TT, Collin P, Järvinen O, Haimila K, Partanen J, Laurila K, Korponay-Szabo IR, Huhtala H, Reunala T, Mäki M. Immunoglobulin A autoantibodies against transglutaminase 2 in the small intestinal mucosa predict forthcoming coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:541-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lähdeaho ML, Kaukinen K, Collin P, Ruuska T, Partanen J, Haapala AM, Mäki M. Celiac disease: from inflammation to atrophy: a long-term follow-up study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;41:44-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Paparo F, Petrone E, Tosco A, Maglio M, Borrelli M, Salvati VM, Miele E, Greco L, Auricchio S, Troncone R. Clinical, HLA, and small bowel immunohistochemical features of children with positive serum antiendomysium antibodies and architecturally normal small intestinal mucosa. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2294-2298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tursi A, Brandimarte G. The symptomatic and histologic response to a gluten-free diet in patients with borderline enteropathy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:13-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dickey W, Hughes DF, McMillan SA. Patients with serum IgA endomysial antibodies and intact duodenal villi: clinical characteristics and management options. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1240-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kurppa K, Collin P, Viljamaa M, Haimila K, Saavalainen P, Partanen J, Laurila K, Huhtala H, Paasikivi K, Mäki M. Diagnosing mild enteropathy celiac disease: a randomized, controlled clinical study. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:816-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 194] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kurppa K, Ashorn M, Iltanen S, Koskinen LL, Saavalainen P, Koskinen O, Mäki M, Kaukinen K. Celiac disease without villous atrophy in children: a prospective study. J Pediatr. 2010;157:373-80, 380.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kurppa K, Collin P, Sievänen H, Huhtala H, Mäki M, Kaukinen K. Gastrointestinal symptoms, quality of life and bone mineral density in mild enteropathic coeliac disease: a prospective clinical trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:305-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wahab PJ, Crusius JB, Meijer JW, Mulder CJ. Gluten challenge in borderline gluten-sensitive enteropathy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1464-1469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |