Published online Jun 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6675

Peer-review started: December 9, 2014

First decision: December 26, 2014

Revised: January 9, 2015

Accepted: February 11, 2015

Article in press: February 11, 2015

Published online: June 7, 2015

Processing time: 184 Days and 23.1 Hours

AIM: To preliminarily investigate the prognostic significance of the platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in patients with gallbladder carcinoma (GBC).

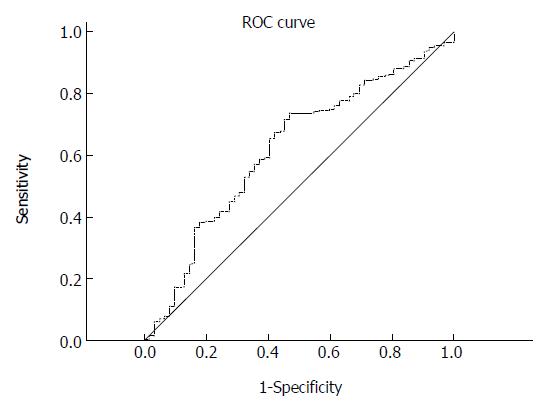

METHODS: Clinical data of 316 surgical GBC patients were analyzed retrospectively, and preoperative serum platelet and lymphocyte counts were used to calculate the PLR. The optimal cut-off value of the PLR for detecting death was determined by the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. The primary outcome was overall survival, which was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. The log-rank test was used to compare the differences in survival. Then, we conducted multivariate Cox analysis to assess the independent effect of the PLR on the survival of GBC patients.

RESULTS: For the PLR, the area under the ROC curve was 0.620 (95%CI: 0.542-0.698, P = 0.040) in detecting death. The cut-off value for the PLR was determined to be 117.7, with 73.6% sensitivity and 53.2% specificity. The PLR was found to be significantly positively correlated with CA125 serum level, tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, and tumor differentiation. Univariate analysis identified carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), CA125 and CA199 levels, PLR, TNM stage, and the degree of differentiation as significant prognostic factors for GBC when they were expressed as binary data. Multivariate analysis showed that CA125 > 35 U/mL, CA199 > 39 U/mL, PLR ≥ 117.7, and TNM stage IV were independently associated with poor survival in GBC. When expressed as a continuous variable, the PLR was still an independent predictor for survival, with a hazard ratio of 1.018 (95%CI: 1.001-1.037 per 10-unit increase, P = 0.043).

CONCLUSION: The PLR could be used as a simple, inexpensive, and valuable tool for predicting the prognosis of GBC patients.

Core tip: The platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR) has been identified as a useful prognostic tool for various types of cancer; however, its prognostic value in gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) has never been investigated. We recruited 316 patients at our institute to determine the significance of the PLR in GBC. It was found to be significantly correlated with the serum level of CA125, tumor-node-metastasis stage, and tumor differentiation. Our results showed that a PLR ≥ 117.7 was independently associated with poor survival in GBC. We emphasize that this ratio could be used as a simple, inexpensive, and valuable tool for predicting the prognosis of GBC.

- Citation: Pang Q, Zhang LQ, Wang RT, Bi JB, Zhang JY, Qu K, Liu SS, Song SD, Xu XS, Wang ZX, Liu C. Platelet to lymphocyte ratio as a novel prognostic tool for gallbladder carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(21): 6675-6683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i21/6675.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i21.6675

Gallbladder carcinoma (GBC) is a rare disease with an increasing morbidity worldwide. The incidence of this malignancy has been recently reported to be approximately 2.5 per 100000 persons[1]. Predisposing factors for GBC mainly include gallstones, chronic cholecystitis, chronic bacterial cholangitis, environmental exposures, etc[2].

Although the diagnosis and treatment of GBC have improved dramatically with the advance in surgical techniques, the prognosis for this malignancy is still typically poor because the majority of patients are diagnosed and treated at a late stage. It has been previously reported that the overall 5-year survival rate of GBC ranges from 2.7% to 20.1%[3,4]. To date, the relative prognostic factors for GBC have not yet been clearly identified, and previous research has suggested that age[5], sex[5], CA125[6] and CA199 levels[7], and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage[5,8] might affect the survival of these patients.

Recently, numerous studies have shown that the inflammatory response plays a crucial role in the formation and development of various malignancies[9,10]. In addition, a high platelet count (PLT) has been found to be associated with poor prognosis in many solid tumors[11]. The platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), which is a combination of the PLT and lymphocyte counts, is also regarded as a representative index of inflammation. An elevation in the PLR has been found to be a negative predictor for survival in patients with colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and ovarian cancer[12,13]. However, the prognostic significance of PLR in GBC, which is one of the malignancies that is strongly associated with chronic inflammation[14], has never been investigated. We therefore conducted a retrospective cohort study to reveal the prognostic value of PLR in GBC.

From 2002 until 2012, a total of 316 surgical GBC patients (238 with radical surgery and 78 without radical surgery) who had complete follow-up information were analyzed at our institute. Patients who had been previously treated for GBC were excluded. In addition, patients who had concomitant diseases that could significantly alter PLT, such as severe hypertension, splenic disease, or blood coagulation disorders, and patients who used aspirin or other acetylsalicylic acid drugs in the month before the surgery were excluded. Similarly, patients who had autoimmune diseases (Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune hepatitis, etc.), leukemia, viral infection-related diseases, or other diseases that influence lymphocyte count were also excluded. Our study complied with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki[15] and was approved by the Ethical Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of the Xi’an Jiaotong University College of Medicine.

We extracted information of potential prognostic factors for GBC from the electronic medical records. Specifically, the following data were collected: age and sex; history of gallstones; history of metabolic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension; PLT; lymphocyte, neutrophil, and white blood cell (WBC) counts; carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), CA125, and CA199 levels, and the results of pathological reports. The TNM staging system (5th edition), based on the criteria of the American Joint Committee on Cancer, was adopted[5].

Resected tumor samples were uniformly sent to the Department of Pathology, and the presence of GBC was determined by clinical pathologists.

After discharge, patients were followed with either abdominal computes tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging scans as well as serological tests, including measurement of CEA, AFP, CA125, and CA199 levels. The follow-up evaluations consisted of the above tests every 3 mo for the first year, every 4 mo for the second year, and every 6 mo thereafter. During follow-up, the date of death and the time of the last follow-up were recorded.

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation for the normally distributed variables (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, P > 0.05), and median (min-max) for the other variables. Comparisons between two groups were performed using the t test or Wilcoxon test for continuous variables and the χ2 test for categorical data. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was adopted to determine the optimal cut-off point (with the highest sum of specificity plus sensitivity) for the PLR for discriminating between deceased and living patients. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Dr. Kai Qu from Department of Epidemiology, MD Anderson Cancer Center, University of Texas, United States.

The primary outcome observed was overall survival (OS), which was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method. Differences in survival were analyzed by the log-rank test. The variables found to be significant (P < 0.05) in the univariate analysis were subjected to multivariate analysis with the backward Wald Cox proportional hazard regression method. All statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 18.0 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). A bilateral P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Demographic data, serological tests, tumor stage, and the characteristics of the study population stratified according to the PLR are summarized in Table 1. The cohort included 101 men and 215 women, with a median age 65 years. Of these, 160, 30, and 57 patients had a history of gallbladder stones, diabetes, and hypertension, respectively. There were 155 (49.05%) patients with lymph node invasion, and 85 (26.9%) patients with remote metastasis. The median survival time of the patients after surgical resection was 9 mo, with 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS probabilities of 37.1%, 18.9%, and 11.8%, respectively. During the median follow-up time of 42 mo, 254 (80.4%) patients died.

| Variable | Overall(n = 316) | PLR < 117.7(n = 100) | PLR≥117.7(n = 216) | P value |

| Age (yr) | 65 (30-87) | 65 (43-87) | 64 (30-87) | 0.1551 |

| Men/Women | 101/215 | 39/61 | 62/154 | 0.0681 |

| Gallstone/No | 160/156 | 50/50 | 110/106 | 0.8781 |

| Diabetes/No | 30/286 | 10/90 | 20/196 | 0.8351 |

| Hypertension/No | 57/259 | 19/81 | 38/178 | 0.7621 |

| PLT (109/L) | 184 (37-525) | 139 (37-261) | 216 (37-525) | < 0.0012 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | 1.3 (0.3-3.5) | 1.6 (0.4-3.5) | 1.1 (0.2-2.9) | < 0.0012 |

| PLR | 152.4 (13.8-2282.6) | 93.6 (13.8-117.6) | 185.5 (117.9-2282.6) | < 0.0012 |

| WBC (109/L) | 6.2 (1.6-33.4) | 5.6 (1.9-33.4) | 6.6 (1.6-23.4) | 0.0132 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 4.2 (1.0-25.9) | 3.4 (1.0-25.9) | 4.6 (1.0-19.3) | < 0.0012 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 3.6 (0.5-264.8) | 3.8 (1.0-90.6) | 3.6 (0.5-264.8) | 0.8472 |

| (n = 168) | (n = 44) | (n = 124) | ||

| AFP (ng/mL) | 2.9 (1.1-615.4) | 3.0 (1.1-53.0) | 2.8 (1.1-615.4) | 0.7632 |

| (n = 150) | (n = 36) | (n = 114) | ||

| CA-125 (U/mL) | 30.8 (6.1-3684) | 21.0 (6.1-345.6) | 36.5 (6.5-3684.0) | 0.0042 |

| (n = 146) | (n = 41) | (n = 105) | ||

| CA-199 (U/mL) | 100.5 (0.5-10000) | 99.6 (0.5-4306) | 125.0 (0.5-10001) | 0.3842 |

| (n = 158) | (n = 45) | (n = 113) | ||

| TNM stage I/II/III/IVA/IVB | 5/24/59/121/107 | 4/12/21/36/27 | 1/12/38/85/80 | 0.0191 |

| Differentiation: | 26/134/156 | 13/48/39 | 13/86/117 | 0.0311 |

| high/moderate/low | ||||

| Survival time (mo) | 9 (1-97) | 12 (1-77) | 8 (1-97) | < 0.0012 |

| Death/No | 254/62 | 71/29 | 183/33 | 0.0041 |

The diagnostic potential of the PLR in detecting death is shown in Figure 1. In general, the PLR was found to be a significant indicator for distinguishing death from survival (area under the ROC curve = 0.620, 95%CI: 0.542-0.698, P = 0.040). The ROC curve showed an optimal cut-off value of 117.7 for the PLR, with 73.6% sensitivity and 53.2% specificity.

As shown in Table 1, the PLR was significantly positively associated with the lymphocyte, WBC, and neutrophil counts, CA125 level, TNM stage, and degree of differentiation (all P < 0.05).

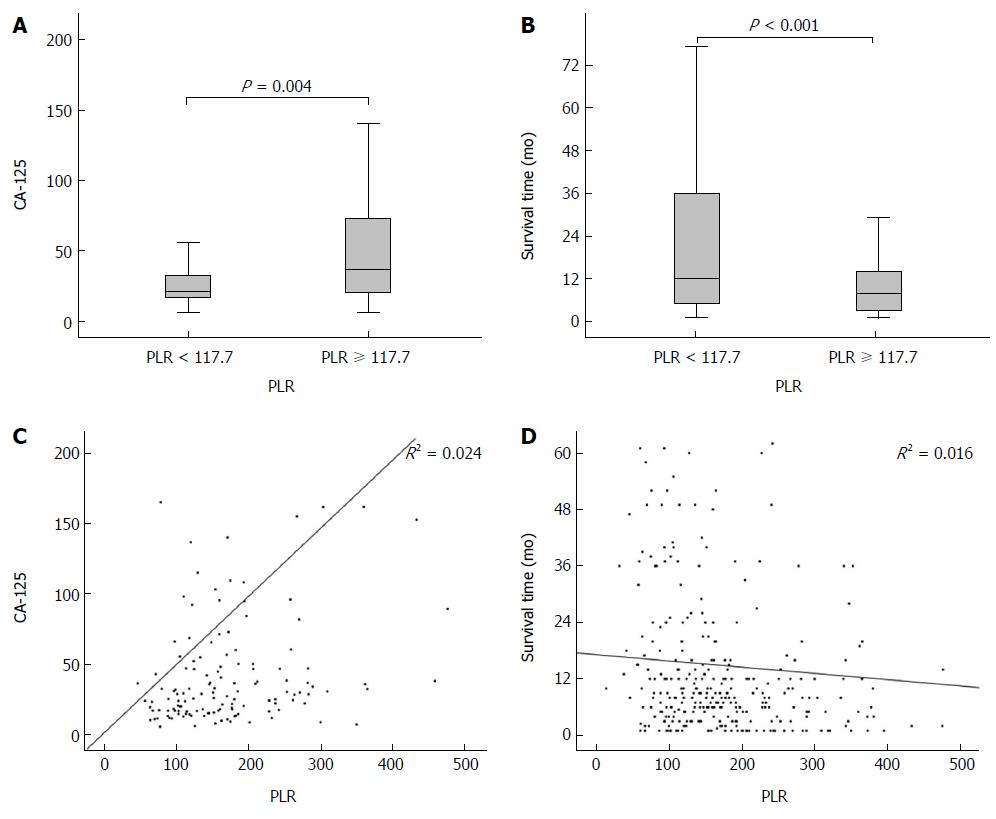

Spearman’s correlation analysis showed that the PLR was significantly associated with the PLT, lymphocyte count, neutrophil count, WBC count, differentiation, and survival time, with Spearman’s coefficients of 0.568, -0.587, 0.356, 0.207, 0.262, 0.181 and -0.237 (all P < 0.01, Table 2), respectively. The box plots revealed the relationship between the PLR and the serum level of CA125 (Figure 2A) and survival time (Figure 2B). Furthermore, Figure 2C and 2D show the linear relationships of the PLR with the CA125 level and survival time.

| Variable | Coefficient | P value |

| Age (yr) | -0.017 | 0.758 |

| Gender | 0.030 | 0.600 |

| PLT (109/L) | 0.568 | < 0.001 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) | -0.587 | < 0.001 |

| Neutrophils (109/L) | 0.356 | < 0.001 |

| WBC (109/L) | 0.207 | < 0.001 |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.032 | 0.678 |

| AFP (ng/mL) | -0.073 | 0.375 |

| CA-125 (U/mL) | 0.262 | 0.001 |

| CA-199 (U/mL) | 0.133 | 0.096 |

| TNM stage | 0.104 | 0.064 |

| Differentiation | 0.181 | 0.001 |

| Survival time (mo) | -0.237 | < 0.001 |

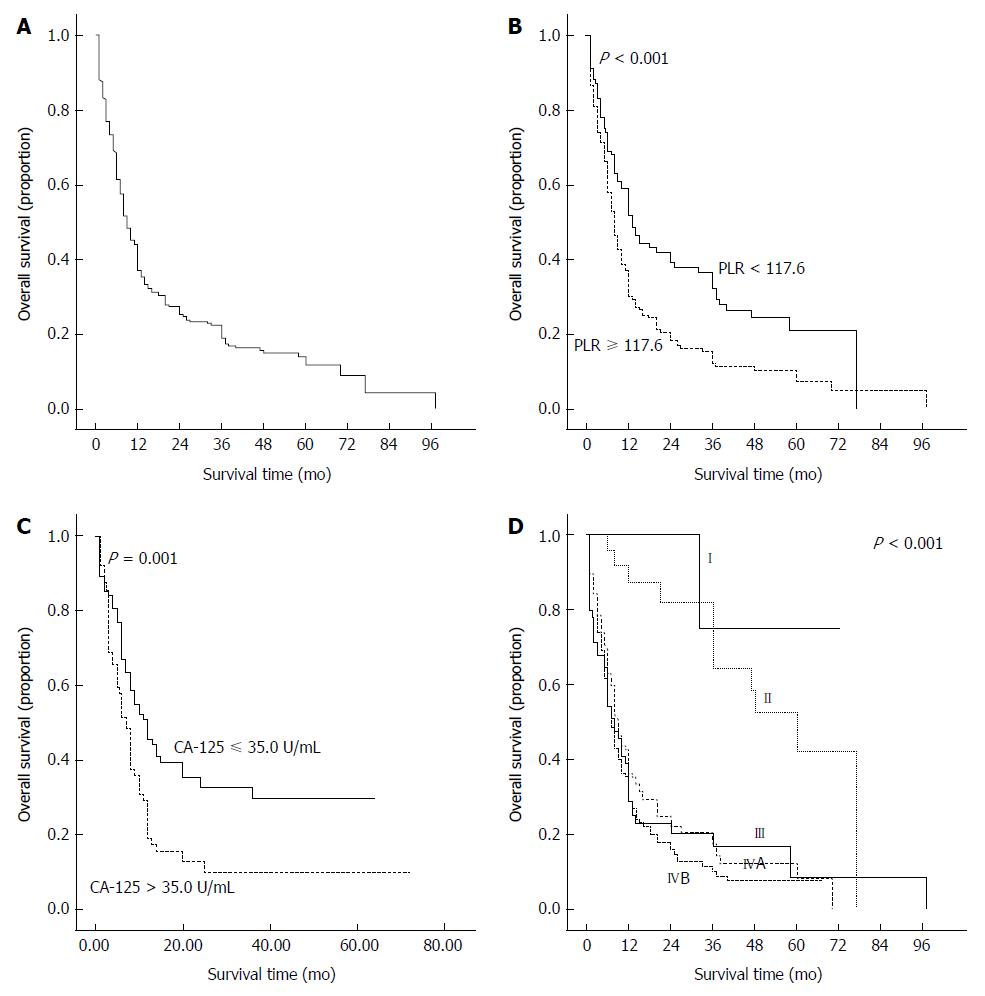

Figure 3A shows the survival curves for our study cohort. Of the clinical parameters, a high PLR, high levels of CA125 and CA199, TNM stage IV, and poor differentiation were found to be significantly associated with poor OS by the log-rank test. Figures 3B to D show Kaplan-Meier curves stratified according to the PLR, CA125 level, and TNM stage, respectively. The respective cumulative survival rates at 1, 3, and 5 years were 51.7%, 32.3%, and 21.0% for patients with a PLR < 117.7, and 30.3%, 12.2%, and 7.4% for those with a PLR ≥ 117.7.

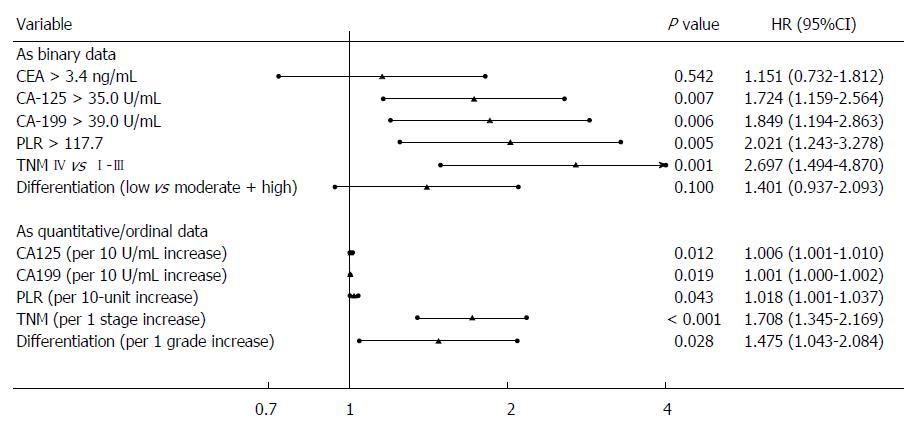

When the parameters were expressed as binary data, univariate analysis identified CEA, CA125, and CA199 levels, TNM stage, degree of differentiation, and PLR as significant tools for predicting OS in patients with GBC (Table 3). However, neither the PLT nor the lymphocyte count was a useful predictor. Multivariate analyses showed that patients with a higher PLR [hazard ratio (HR): 2.02; 95%CI: 1.24-3.28], a higher CA125 level (HR: 1.72; 95%CI: 1.16-2.56), a higher CA199 level (HR: 1.85; 95%CI: 1.19-2.86), and TNM stage IV (HR: 2.70; 95%CI: 1.49-4.87) had a significantly poorer prognosis compared with those with lower levels of these factors or a lower TNM stage (Figure 4).

| As binary data | As quantitative/ordinal data | ||||

| Variable | P value | HR (95%CI) | Variable | P value | HR (95%CI) |

| Age > 60 yr | 0.574 | 1.078 (0.829-1.403) | Age (per 1 yr increase) | 0.456 | 1.004 (0.993-1.016) |

| Women vs men | 0.829 | 1.030 (0.788-1.345) | |||

| Gallstone (yes vs no) | 0.309 | 1.137 (0.887-1.458) | |||

| Diabetes (yes vs no) | 0.420 | 1.194 (0.777-1.835) | |||

| Hypertension (yes vs no) | 0.997 | 1.001 (0.725-1.382) | |||

| CEA > 3.4 ng/mL | 0.012 | 1.620 (1.114-2.355) | CEA (per 1 ng/mL increase) | 0.071 | 1.005 (1.000-1.011) |

| AFP > 20 ng/mL | 0.420 | 0.663 (0.244-1.801) | AFP (per 1 ng/mL increase) | 0.296 | 0.997 (0.990-1.003) |

| CA-125 > 35.0 U/mL | 0.002 | 1.813 (1.236-2.658) | CA-125 (per 10 U/mL increase) | 0.027 | 1.005 (1.001-1.009) |

| CA-199 > 39.0 U/mL | 0.002 | 1.930 (1.284-2.903) | CA-199 (per 10 U/mL increase) | 0.028 | 1.001 (1.000-1.002) |

| PLT > 300 × 109/L | 0.956 | 1.013 (0.647-1.594) | PLT (per 109/L increase) | 0.053 | 1.001 (1.000-1.003) |

| Lymphocytes | 0.243 | 1.173 (0.897-1.534) | Lymphocytes (per 109/L increase) | 0.064 | 0.801 (0.633-1.013) |

| < 1.5 × 109/L | |||||

| PLR ≥ 117.7 | < 0.001 | 1.644 (1.246-2.169) | PLR (per 10 increase) | 0.023 | 1.007 (1.001-1.013) |

| TNM IV vs I-III | < 0.001 | 1.692 (1.260-2.274) | TNM (per 1 stage increase) | < 0.001 | 1.377 (1.213-1.564) |

| Differentiation (low vs moderate/high) | < 0.001 | 1.563 (1.217-2.006) | Differentiation (per 1 grade increase) | < 0.001 | 1.523 (1.256-1.845) |

We then assessed the prognostic values of these parameters when they were expressed as quantitative or ordinal data. Similarly, univariate analysis identified the same significant factors (Table 3), and multivariate analysis added the degree of differentiation as another independent prognostic factor (Figure 4).

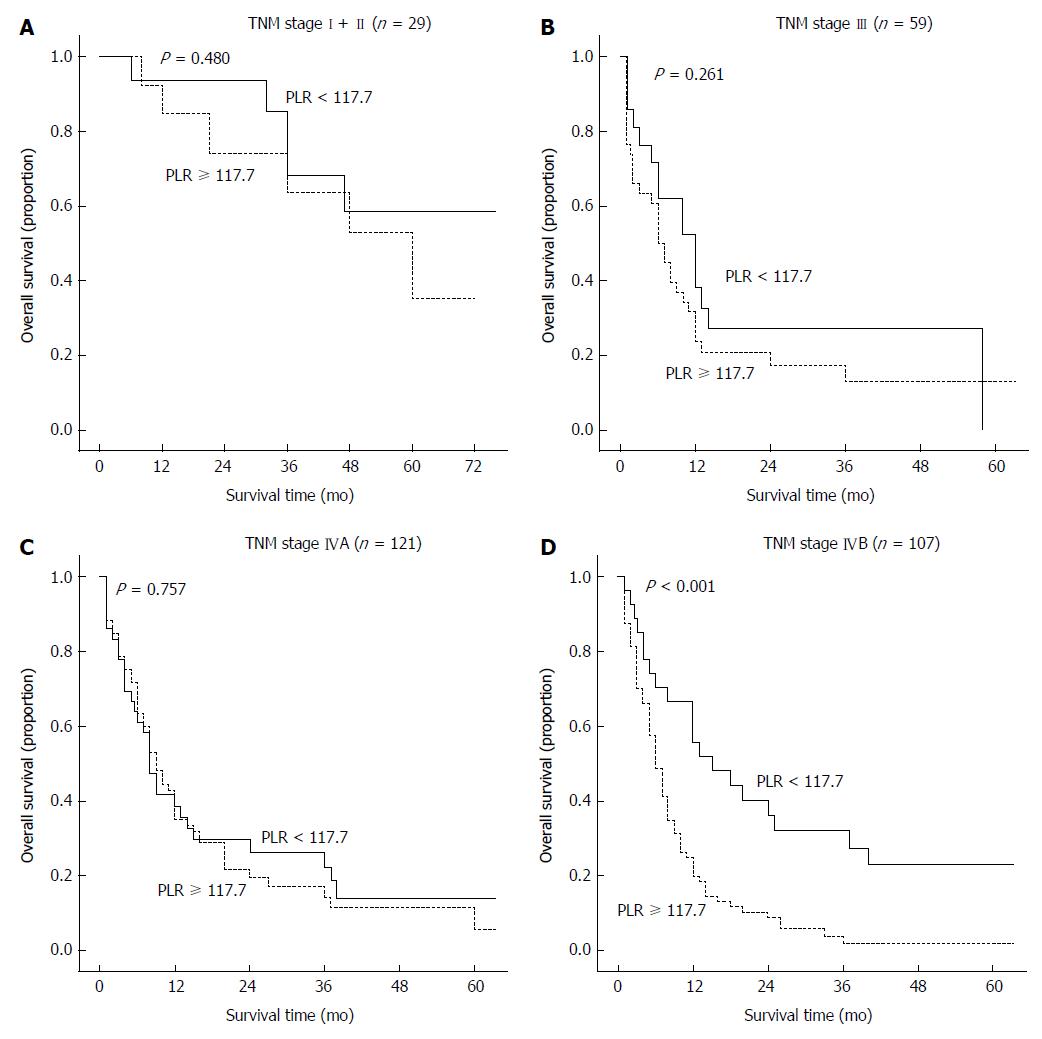

TNM stage is considered to be a crucial prognostic factor for GBC, and it was the most powerful predictor in our survival analysis. To clarify whether the subgroups of GBC patients could be negatively influenced by the PLR, the patients were classified according to TNM stage. A high PLR was found to significantly increase the recurrence probability in GBC patients with TNM stage IVB but not with any of the other stages (Figure 5).

GBC is a rare disease; however, it is the most common malignant tumor of the biliary tract and represents 46%-95% of all biliary tract malignancies worldwide[1,16]. The incidence of GBC differs worldwide, with high prevalences in Chile, Japan, and northern India[16]. Few valuable prognostic factors for GBC have been identified, and it is necessary to identify several novel biomarkers.

Gallstones are a major risk factor for GBC[2]. However, it is unknown whether there presence is a useful prognostic factor for this disease. Our study showed no significant association between gallstones and the survival of patients with GBC, which is consistent with a previous small-sample study conducted by Shiba et al[17]. Kayahara et al[5] have demonstrated that men and aged patients with GBC have decreased survival times; however, neither of these factors significantly affected survival time in our cohort. Ren and his colleagues[18] performed a meta-analysis of 21 studies and concluded that diabetes mellitus increased the incident risk of GBC by 52%. In contrast, our study showed no links between diabetes mellitus and the prognosis of GBC.

Recent studies have shown that an abnormal PLT[19] or lymphocyte count alone[20] are predictive of poor survival in patients with GBC. However, in our cohort, neither the PLT count alone nor the lymphocyte count alone was able to significantly predict survival. However, the PLR, which is a simple combined index, strengthened both the role of PLTs and the significance of lymphocytes and was a powerful independent predictor. We confirmed the prognostic significance of the PLR both when it was expressed as binary data and when it was used as a continuous variable. In addition, TNM stage was identified as the other most useful tool for predicting the outcome of GBC.

Obviously, the possible mechanisms underlying the prognostic role of the PLR in the survival of GBC patients could involve two factors, the PLT and lymphocyte counts. On the one hand, although the PLT count was not a significant indicator of survival time in our study, a high level of PLTs has been previously reported to significantly increase the risk of death from various cancers[11], including GBC[6,19]. Moreover, an elevated serum level of PLTs has been positively correlated with tumor size[21]. In vitro, PLTs accelerate the growth and invasion of tumors via the release of platelet-derived proangiogenic mediators[22,23]. On the other hand, previous data have also shown that a lymphocyte count of less than 1000/μL is a predictor of poor outcome in GBC[20]. Furthermore, the lymphocyte count has been found to be negatively correlated with TNM stage[20]. Dunn et al[24] have demonstrated the cancer immune-surveillance role of lymphocytes, by which lymphocytes can prevent tumor development. In addition, we showed the positive associations between the PLR and the CA125 level as well as the TNM stage, which were important prognostic factors for GBC.

This study is the first to demonstrate a link between the PLR and survival in patients with GBC. Inevitably, there were some limitations in the current study. First, the PLR was a useful tool only for the assessment of the GBC patients with TNM stage IVB, but not in those with any of the other stages. The limited sample size evaluated for each TNM stage, particularly stages I-III (Figure 5), may have been the main reason for the limited utility of the PLR. Second, to obtain more data, we did not distinguish between patients who underwent radical surgery and those who received palliative cholecystectomy or extended resection. Finally, our results were obtained from data collected at a single center, and there is a need for further large, multicenter cohort studies to validate our findings.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that the PLR could be used as a simple, inexpensive, and valuable tool for predicting the prognosis of GBC patients.

We sincerely thank Dr. Wei Chen, Yan-Yan Zhou, and Rui-Chen Miao at the Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, the First Affiliated Hospital of Medical College, Xi’an Jiaotong University for their support in the collection of patient data.

Gallbladder cancer (GBC) is a rare disease associated with poor survival. The overall 5-year survival rate ranges from 2.7% to 20.1%. To date, the relative prognostic factors of GBC have not been clearly identified. Recently, numerous studies have shown that the inflammatory response plays a crucial role in the formation and development of various malignancies. The platelet to lymphocyte ratio (PLR), which is a combination of the platelet and lymphocyte counts, is regarded as a representative index of inflammation.

The PLR has been identified as a significant prognostic tool for various types of cancer. An elevation in the PLR has been determined to be a negative predictor for survival in patients with colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, etc. The current study demonstrates that the PLR may be a valuable tool for predicting the prognosis of GBC patients.

Recent studies have identified the platelet and lymphocyte counts as significant prognostic factors for GBC. In contrast, this study is the first to suggest that the PLR, which is a combination of the platelet and lymphocyte counts, is an independent prognostic factor for GBC regardless of whether binary data or continuous variables are used. In addition, the PLR is more valuable than the platelet or lymphocyte count alone. Patients with a PLR ≥ 117.7 have poorer survival compared with those with a low PLR, especially for those with TNM stage IVB.

By simply measuring the platelet and lymphocyte counts before surgery, we were able to estimate postoperative survival for patients with GBC. This finding may also be used to improve the prognosis of GBC patients by improving the preoperative PLR.

The platelet count is a reflection of platelet function, and it normally ranges from 100 × 109/L-300 × 109/L. Lymphocytes are a type of white blood cell, and their levels normally range from 1.1 × 109/L-3.2 × 109/L in adults.

This study is well supported by the data, and the authors have confirmed the predictive power of the PLR for a rare malignancy for the first time in the literature. The findings of this study were supported by adequate statistical analyses.

P- Reviewer: Baranyai Z, Yang H S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Cant MR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Boutros C, Gary M, Baldwin K, Somasundar P. Gallbladder cancer: past, present and an uncertain future. Surg Oncol. 2012;21:e183-e191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Rakić M, Patrlj L, Kopljar M, Kliček R, Kolovrat M, Loncar B, Busic Z. Gallbladder cancer. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr. 2014;3:221-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Manfredi S, Benhamiche AM, Isambert N, Prost P, Jouve JL, Faivre J. Trends in incidence and management of gallbladder carcinoma: a population-based study in France. Cancer. 2000;89:757-762. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, Zhang S, Zou X, Wang N, Zhang L, Tang J, Chen J, Wei K. Cancer survival in China, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:1921-1930. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 415] [Cited by in RCA: 499] [Article Influence: 49.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kayahara M, Nagakawa T, Nakagawara H, Kitagawa H, Ohta T. Prognostic factors for gallbladder cancer in Japan. Ann Surg. 2008;248:807-814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wu XS, Shi LB, Li ML, Ding Q, Weng H, Wu WG, Cao Y, Bao RF, Shu YJ, Ding QC. Evaluation of two inflammation-based prognostic scores in patients with resectable gallbladder carcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21:449-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang YF, Feng FL, Zhao XH, Ye ZX, Zeng HP, Li Z, Jiang XQ, Peng ZH. Combined detection tumor markers for diagnosis and prognosis of gallbladder cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:4085-4092. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 8. | Pilgrim CH, Groeschl RT, Turaga KK, Gamblin TC. Key factors influencing prognosis in relation to gallbladder cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:2455-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, Balkwill F. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature. 2008;454:436-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8581] [Cited by in RCA: 8327] [Article Influence: 489.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mantovani A, Romero P, Palucka AK, Marincola FM. Tumour immunity: effector response to tumour and role of the microenvironment. Lancet. 2008;371:771-783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 565] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Buergy D, Wenz F, Groden C, Brockmann MA. Tumor-platelet interaction in solid tumors. Int J Cancer. 2012;130:2747-2760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhou X, Du Y, Huang Z, Xu J, Qiu T, Wang J, Wang T, Zhu W, Liu P. Prognostic value of PLR in various cancers: a meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e101119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 244] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, Al-Mubarak M, Vera-Badillo FE, Hermanns T, Seruga B, Ocaña A, Tannock IF, Amir E. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23:1204-1212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 500] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Li Y, Zhang J, Ma H. Chronic inflammation and gallbladder cancer. Cancer Lett. 2014;345:242-248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310:2191-2194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16597] [Cited by in RCA: 18330] [Article Influence: 1527.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hundal R, Shaffer EA. Gallbladder cancer: epidemiology and outcome. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 490] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shiba H, Misawa T, Fujiwara Y, Futagawa Y, Furukawa K, Haruki K, Iwase R, Iida T, Yanaga K. Glasgow prognostic score predicts outcome after surgical resection of gallbladder cancer. World J Surg. 2015;39:753-758. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ren HB, Yu T, Liu C, Li YQ. Diabetes mellitus and increased risk of biliary tract cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Causes Control. 2011;22:837-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ong SL, Garcea G, Thomasset SC, Neal CP, Lloyd DM, Berry DP, Dennison AR. Ten-year experience in the management of gallbladder cancer from a single hepatobiliary and pancreatic centre with review of the literature. HPB (Oxford). 2008;10:446-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Iwase R, Shiba H, Haruki K, Fujiwara Y, Furukawa K, Futagawa Y, Wakiyama S, Misawa T, Yanaga K. Post-operative lymphocyte count may predict the outcome of radical resection for gallbladder carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:3439-3444. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Carr BI, Guerra V. Thrombocytosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1790-1796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Carr BI, Cavallini A, D’Alessandro R, Refolo MG, Lippolis C, Mazzocca A, Messa C. Platelet extracts induce growth, migration and invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sierko E, Wojtukiewicz MZ. Platelets and angiogenesis in malignancy. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2004;30:95-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dunn GP, Old LJ, Schreiber RD. The immunobiology of cancer immunosurveillance and immunoediting. Immunity. 2004;21:137-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1843] [Cited by in RCA: 2014] [Article Influence: 95.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |