Published online May 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6404

Peer-review started: December 16, 2014

First decision: January 8, 2015

Revised: February 14, 2015

Accepted: March 27, 2015

Article in press: March 27, 2015

Published online: May 28, 2015

Processing time: 167 Days and 5 Hours

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract that are most commonly found in the stomach. Although GISTs can spread to the liver and peritoneum, metastasis to the skeletal muscle is very rare and only four cases have previously been reported. These cases involved concurrent skeletal metastases of primary GISTs or liver metastases. Here, we report the first case of a distant recurrence in the brachialis muscle after complete remission of an extra-luminal gastric GIST following a wedge resection of the stomach, omental excision, and adjuvant imatinib therapy for one year. Ten months after therapy completion, the patient presented with swelling and tenderness in the left arm. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a large mass in the brachialis muscle, which showed positivity for c-kit and CD34 upon pathologic examination. This is the first reported case of a solitary distant recurrence of a GIST in the muscle after complete remission had been achieved.

Core tip: This report presents the first case of the solitary distant recurrence of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor in skeletal muscle after complete remission had been achieved. This case, along with previous reports, indicates that an extended period of tyrosine-kinase inhibitor therapy may reduce metastasis and recurrence in patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors.

- Citation: Jin SS, Jeong HS, Noh HJ, Choi WH, Choi SH, Won KY, Kim DP, Park JC, Joung MK, Kim JG, Sul HJ, Lee SW. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor solitary distant recurrence in the left brachialis muscle. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(20): 6404-6408

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i20/6404.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i20.6404

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common malignant mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, accounting for 1% to 3% of all malignant GI tumors. These tumors can develop from very early forms of interstitial cells of Cajal in the wall of the GI tract[1]. Although GISTs can develop anywhere along the GI tract, 60%-70% are well-circumscribed lesions within the wall of the stomach, and 20%-30% arise in the small intestine[2-4]. Approximately 5% of all GIST cases arise from outside the GI tract, and occur in the mesentery, omentum, and retroperitoneum[5].

The most common metastatic sites for GISTs are the liver and peritoneum, and are less frequently found in bone or lung, and rarely in skeletal muscle[6]. Only four cases of GIST metastasis to the skeletal muscle have been reported in the English literature[7-10]. Here we present a rare case of primary GIST with a distant recurrence in the skeletal muscle following complete remission.

An 80-year-old woman with Parkinson’s disease and hypertension was admitted for pain and swelling of the left arm. She had undergone omental excision with a wedge resection of a large (23 cm × 18 cm × 5 cm) pedunculated extra-luminal gastric GIST that was attached to the stomach three years previously. Sectioning revealed that the specimen had solid, myxoid features with necrosis and hemorrhage. Pathology showed CD117 (c-kit) positivity in the excised portion of the stomach and the omental mass. There were < 5 mitoses per 50 high-power fields (HPFs). She was subsequently diagnosed with a high-risk gastric GIST with omental invasion. She received adjuvant imatinib therapy for one year and complete remission was confirmed. She was observed regularly thereafter as an outpatient.

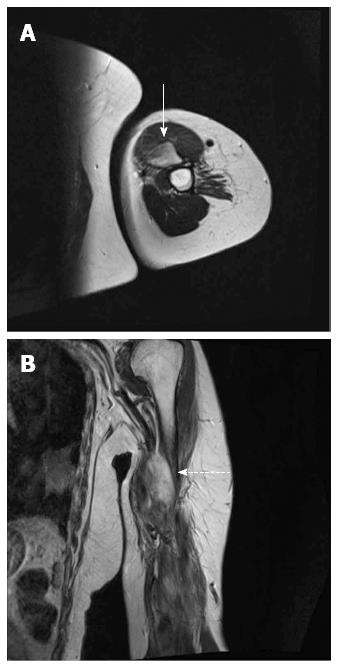

Ten months after the termination of imatinib therapy, she was admitted to our center after developing pain and swelling of the left arm. On physical examination, the sensory and motor functions of the distal part of the left arm were normal, and an X-ray did not indicate any bony abnormalities. The symptoms persisted for an additional three months, with increasing tenderness of the arm. Upon readmission, laboratory findings for aspartate aminotransferase (23 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (19 IU/L), and creatine phosphokinase (137 IU/L) were within normal ranges, whereas the hemoglobin level (10.6 g/dL) was below normal and the lactate dehydrogenase (492 IU/L) was high. Although another X-ray failed to show an abnormality, a huge mass in the brachialis muscle was revealed by magnetic resonance imaging (Figure 1). Positron-emission tomography showed an area of increased metabolic activity in the left arm with irregular uptake (Figure 2). Further imaging did not reveal other abnormalities at other sites indicative of metastases.

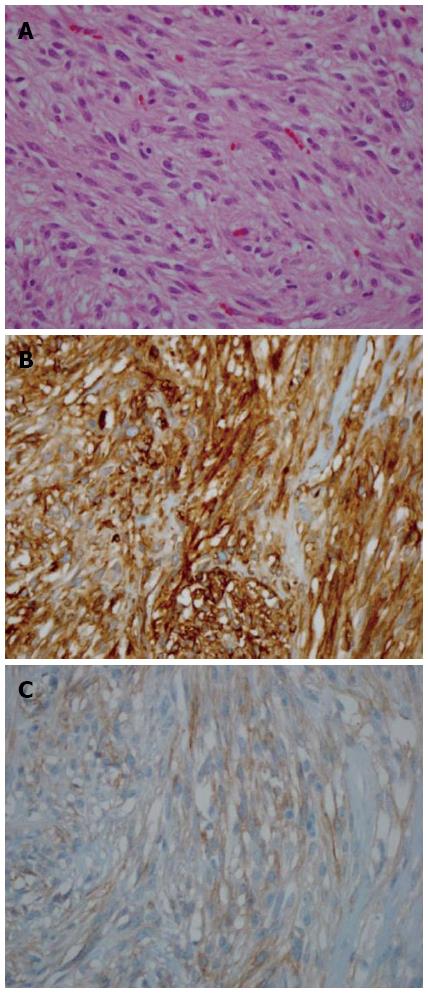

An incisional biopsy of the left brachialis muscle was performed, revealing spindle-shaped cells positive for c-kit and CD34 (Figure 3). She was diagnosed with muscle recurrence of GIST and was again treated with imatinib (400 mg daily). Surgical resection of the solitary metastatic muscle mass was not performed due to her poor condition and high-risk GIST. Magnetic resonance imaging after three months of imatinib therapy showed that the mass was slightly decreased in size. However, she discontinued imatinib two months later because of severe nausea and vomiting. Three months after discontinuing imatinib therapy, her general condition deteriorated, and she was discharged to another healthcare facility for conservative management.

GISTs rarely metastasize to the soft tissue, bone, or skeletal muscle[11], which is particularly resistant to metastatic cancer. Mechanical injury is one of the mechanisms responsible for this resistance. For example, deformation of the cancer cells by microvessels near the muscle ultimately destroys the cells once a critical level of negative pressure is reached[12,13]. Additionally, muscle contraction kills cells trapped within the muscle capillaries, whereas cancer cell survival is greatest in denervated relaxed muscle[14]. Most cancer cells die after hematogenous spread to muscle because of the unfavorable metabolic and mechanical environment in normal muscles[13]. However, injured muscle tissue may provide a more favorable mechanical or metabolic environment for metastatic cancer cell survival[7,13].

Rare metastasis to skeletal muscle was reported by Pasku et al[7] in a case involving bilateral gluteal muscles and lung metastasis of intrapelvic GISTs. The patient was successfully treated with tumorectomy and imatinib for one year. Bashir et al[8] reported a case with upper back muscle, adrenal gland, and cardiac metastases of small intestine GISTs; the patient underwent surgical resection and received imatinib treatment. The effect of treatment was not reported. Suzuki et al[9] reported metastasis of small intestine GISTs to the left buttock muscle in a patient who was treated only with chemotherapy because of a misdiagnosed leiomyosarcoma. Small intestine GISTs were later detected and the patient received surgical resection and imatinib treatment, though he died from GI bleeding six months after the initial diagnosis. The fourth case of skeletal metastasis was reported by Cichowitz et al[10], which described a patient with liver metastasis after resection of small intestine GISTs. Following an extended right hepatectomy, an adductor longus muscle metastasis of the small intestine GISTs was detected. Unlike these previous reports, the patient in the present case did not develop concurrent skeletal metastasis. This is the first known report of a distant recurrence in skeletal muscle after achieving complete remission with adjuvant imatinib therapy.

Interestingly, three of the five known cases of muscle metastasis were derived from GISTs of the small intestine. Although most GISTs occur in the stomach, overtly malignant behavior is less commonly seen in gastric tumors[15]. In contrast, tumors of small-bowel origin tend to have more aggressive behavior, and thus a worse prognosis, than of tumors originating in other gastrointestinal sites[15,16]. According to the criteria of the National Institutes of Health, tumor size and the number of mitoses per HPF are predictive of GIST recurrence[11,17]. Moreover, > 5 mitoses/50 HPF and a tumor size > 10 cm are associated with an increased risk of recurrence[3]. The patient described in this report therefore had a very aggressive GIST with a high probability of recurrence, with a mitotic count < 5/50 HPF but a tumor size > 10 cm.

Almost all of the cases of skeletal metastasis of GISTs were treated with imatinib, which is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI). Prior to the discovery of the c-kit tyrosine kinase receptor in GISTs and the antitumor effects of imatinib, surgical removal was the only viable treatment option, as conventional chemotherapy and radiation were largely ineffective[17]. When used as adjuvants following complete surgical resection, molecular-targeted therapies, such as imatinib, can reduce the frequency of recurrence[4,17]. Furthermore, Joensuu et al[18] showed that prolonged treatment (three years vs one year) with imatinib results in longer recurrence-free and overall survival in GIST patients. Indeed, the median duration of survival of patients with advanced GIST increases with the use of TKIs[19]. Thus, it is important to continue imatinib for at least three years to prevent metastasis or recurrence of GISTs in high-risk patients. Unfortunately, the imatinib therapy for the patient in the present case was limited to one year by her medical insurance. However, medical insurance in South Korea has recently been changed to allow for three years of imatinib treatment for patients with a GIST.

In conclusion, this report presents a rare case of GIST metastasis to skeletal muscle, and the first known case of solitary distant recurrence of GIST in the brachialis muscle after complete remission. Similar diagnoses should be considered in patients presenting with suggestive symptoms and signs, even if the site of metastasis is unusual. Moreover, maintenance of TKI therapy for a minimum of three years should be recommended for patients with GISTs.

An 80-year-old woman who had previously undergone wedge resection of an extra-luminal gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) presented with pain and swelling of the left arm.

On physical examination, swelling of the left arm was observed, which persisted for three months with increasing tenderness.

Leiomyoma; leiomyosarcoma; schwannoma.

The patient was anemic (hemoglobin, 10.6 g/dL) and had an elevated level of lactate dehydrogenase (492 IU/L).

T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging revealed a huge, ill-defined high-signal-intensity mass while positron-emission tomography showed an area of increased metabolic activity in the left brachialis muscle with irregular uptake.

Histopathologic findings of the left brachialis muscle mass showed spindle-shaped cells with elongated blunt nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm; immunohistochemical staining showed positivity for c-kit and CD34.

The patient had a wedge resection of the gastric GIST with adjuvant imatinib therapy; after the distant recurrence of left brachialis muscle, she was again treated with imatinib (400 mg daily).

Only four cases of GIST with metastasis to the skeletal muscle have been reported in the literature, however, this is the first report of a distant muscle recurrence.

GISTs are mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract that are most commonly found in the stomach.

This is the first reported case of a solitary distant recurrence of GIST in the brachialis muscle after complete remission and we recommend that similar diagnoses should be considered in patients presenting with suggestive symptoms and signs, even if the site of metastasis is unusual.

This article highlights the distant recurrence of a GIST in the muscle after complete remission with adjuvant imatinib, and highlights the importance of prolonged TKI therapy (≥ 3 years) to prevent recurrence and metastasis.

P- Reviewer: Li YY, Matsuda A, Yang F S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, Meis-Kindblom JM. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumors show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1259-1269. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Corless CL, Fletcher JA, Heinrich MC. Biology of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3813-3825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 847] [Cited by in RCA: 838] [Article Influence: 39.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Mucciarini C, Rossi G, Bertolini F, Valli R, Cirilli C, Rashid I, Marcheselli L, Luppi G, Federico M. Incidence and clinicopathologic features of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. A population-based study. BMC Cancer. 2007;7:230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rammohan A, Sathyanesan J, Rajendran K, Pitchaimuthu A, Perumal SK, Srinivasan U, Ramasamy R, Palaniappan R, Govindan M. A gist of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A review. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;5:102-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Miettinen M, Monihan JM, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Kovatich AJ, Carr NJ, Emory TS, Sobin LH. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors/smooth muscle tumors (GISTs) primary in the omentum and mesentery: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 26 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1109-1118. [PubMed] |

| 6. | DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, Mudan SS, Woodruff JM, Brennan MF. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51-58. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pasku D, Karantanas A, Giannikaki E, Tzardi M, Velivassakis E, Katonis P. Bilateral gluteal metastases from a misdiagnosed intrapelvic gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J Surg Oncol. 2008;6:139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bashir U, Qureshi A, Khan HA, Uddin N. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor with skeletal muscle, adrenal and cardiac metastases: an unusual occurrence. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2011;54:362-364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Suzuki K, Yasuda T, Nagao K, Hori T, Watanabe K, Kanamori M, Kimura T. Metastasis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor to skeletal muscle: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2014;8:256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cichowitz A, Thomson BN, Choong PF. GIST metastasis to adductor longus muscle. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:490-491. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum Pathol. 2008;39:1411-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Weiss L, Clement K. Studies on cell deformability. Some rheological considerations. Exp Cell Res. 1969;58:379-387. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Weiss L. Biomechanical destruction of cancer cells in skeletal muscle: a rate-regulator for hematogenous metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1989;7:483-491. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Weiss L. Biomechanical destruction of cancer cells in the heart: a rate regulator for hematogenous metastasis. Invasion Metastasis. 1988;8:228-237. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Burkill GJ, Badran M, Al-Muderis O, Meirion Thomas J, Judson IR, Fisher C, Moskovic EC. Malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor: distribution, imaging features, and pattern of metastatic spread. Radiology. 2003;226:527-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 272] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Emory TS, Sobin LH, Lukes L, Lee DH, O’Leary TJ. Prognosis of gastrointestinal smooth-muscle (stromal) tumors: dependence on anatomic site. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:82-87. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Trent JC, Benjamin RS. New developments in gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18:386-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Joensuu H, Eriksson M, Sundby Hall K, Hartmann JT, Pink D, Schütte J, Ramadori G, Hohenberger P, Duyster J, Al-Batran SE. One vs three years of adjuvant imatinib for operable gastrointestinal stromal tumor: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2012;307:1265-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 52.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kroep JR, Bovée JV, van der Molen AJ, Hogendoorn PC, Gelderblom H. Extra-abdominal subcutaneous metastasis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor: report of a case and a review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:565-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |