INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises two distinct but related chronic relapsing inflammatory conditions affecting different parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Crohn’s disease (CD) is characterised by a patchy transmural inflammation affecting both small and large bowel segments with several distinct phenotypic presentations. Ulcerative colitis (UC) classically presents as mucosal inflammation of the rectosigmoid (distal colitis), variably extending in a contiguous manner more proximally through the colon but not beyond the caecum (pancolitis) except rarely when backwash ileitis features. This article highlights aspects of the presentation, diagnosis, and management of IBD that have relevance for paediatric practice with particular emphasis on surgical considerations. Since 25% of IBD cases present in childhood or teenage years, the unique considerations and challenges of paediatric management should be widely appreciated. Conversely, we argue that the organizational separation of the paediatric and adult healthcare worlds has often resulted in late adoption of new approaches particularly in paediatric surgical practice.

INCIDENCE

A prospective United Kingdom survey of childhood IBD showed that the incidence was 5.2 per 100000 children per year. In terms of disease distribution 60% were diagnosed as CD and 28% as UC. The remaining 12% could not be classified, and were labelled as indeterminate colitis (IC)[1]. The mean age at diagnosis was 12 years with 5% presenting at less than 5 years of age[2]. The United Kingdom data are similar to a systematic review of North American paediatric cohorts suggesting an incidence of 3-4 per 100000[3]. A recent systematic review comparing time-trend analyses across the age spectrum demonstrated that in 75% of CD studies and 60% of UC studies, the incidence of IBD had significantly increased[4].

PATHOGENESIS

A detailed analysis of progress in understanding the aetiology of IBD is beyond the scope of this article. Suggested mechanisms include the influence of a variety of possible environmental factors triggering an inflammatory response which then persists in a genetically susceptible individual, according to the Knudsen “two-hit” hypothesis. A number of candidate IBD genes have been identified since the CARD15/NOD2 gene was identified on chromosome 16[5]. By 2011, genome-wide association studies had demonstrated 99 non-overlapping gene loci associated with CD and UC, including 28 that are shared, suggesting common mechanisms of pathogenesis[6]. These studies have provided “molecular pointers” to the underlying pathophysiological processes which might be implicated in IBD, including epithelial barrier function, epithelial cell regeneration, microbial defence, innate immune regulation, generation of reactive oxygen species, autophagy, and regulation of adaptive immunity. Even at the level of the individual candidate gene locus, these interactions are complex. For example NOD2 is currently implicated in autophagy, viral recognition and T cell activation[7]. The genes implicated in UC and CD overlap, as do those implicated in childhood- and adult-onset IBD, indicating both common mechanisms of pathogenesis and genetic predisposition. Disease concordance rates in monozygotic twin studies are 10%-15% in UC and 30%-35% in CD, suggesting that non-genetic factors may have greater influence in the pathogenesis of UC[8]. The relationship between genotype and either locational phenotype or behaviour of disease are complex and have at times yielded conflicting results.

The NOD2/CARD15 gene association with CD has been most extensively studied and has been linked to defective Toll receptor-mediated macrophage opsonisation of pathogenic bacteria. NOD2 variants have been associated with the fibrostenosing phenotype, more aggressive disease progression, and ileocaecal presentation[9], although their relation to surgical recurrence has produced contradictory results. “Wild type” gene expression at this locus has been correlated with more favourable response of Crohn’s fistulae to antibiotics[10]. In respect of perianal disease phenotype, the influence of dysfunctional gene expression for both the carnitine/organic cation transporter OCTN[11], and immunity-related GTP-ase family M protein (IRGM)[12,13] on chromosome 5q31 (IBD5) seem to be more specifically related to both fistula and abscess incidence, possibly via defective oxygen burst-mediated bactericidal function, and defects in bacterial autophagy respectively. Although IBD has a multigenic aetiology, each of modest contribution to overall pathogenesis, it remains possible that future advances in genotype studies will identify behavioural subtypes which have significant therapeutic consequence.

Basic science research has focussed on the gut/environmental interface and the various mechanisms maintaining its integrity, the inflammatory process including cell signalling, cytokine responses, the specific gut microbiome and cellular immune defences. Various epidemiological studies have implicated diet, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, smoking, migration and vaccination status in the pathogenesis of CD[14].

DIAGNOSIS AND MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

The configuration of United Kingdom medical services has resulted in the paediatric gastroenterologist being the focal point of referral for children with suspected IBD. Moreover, the specialist endoscopic skills required for diagnosis are now less readily available within paediatric surgical departments[15]. Thus the diagnosis of IBD in childhood is largely the domain of the gastroenterologist. Despite this it is vitally important that any surgeon managing children should be aware of the common presenting features of inflammatory bowel disease, both to ensure that the child is appropriately investigated and to avoid premature ill-conceived surgical intervention. The most common presentations to surgical services are for investigation of rectal bleeding, anal pain, and acute exacerbations of abdominal pain. It is very uncommon for surgical intervention to be required before appropriate diagnostic endoscopic and radiological tests have established the type and extent of IBD, allowing opportunity for appropriate targeted medical management.

Any surgeon treating children with IBD should have a working knowledge of the medical treatment options, their efficacy, side effects and psychosocial impact, to ensure that when a surgical option is under consideration with its potential attendant morbidity, the child and his parents are fully aware of the advantages and disadvantages of all management strategies. Joint clinics staffed by a gastroenterologist, specialist surgeon, dietician and nurse specialist constitute the ideal venue for difficult discussions where clinical decision making is often highly nuanced.

DIAGNOSIS

All children suspected of IBD require full history and examination including assessment of growth velocity and pubertal staging. A minority (25%) of children with CD present with the classic triad of abdominal pain, diarrhoea and weight loss. A high index of suspicion should be maintained in children presenting with vague complaints such as lethargy, anorexia and impaired growth or delayed puberty[2]. The development of standardised diagnostic criteria (the Porto criteria) by the IBD working group of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) has done much to ensure uniformity in diagnosis and management[16].

The gold standard in diagnosis is combined upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (including ileal intubation), together with small bowel radiology. Additional laboratory investigations are adjunctive, but should always include inflammatory markers (ESR, platelets and CRP), nutritional markers (albumin), and liver function tests because of the association of primary sclerosing cholangitis with UC. Stool cultures are mandatory to exclude an infective colitis. Absence of elevated faecal inflammatory surrogate markers calprotectin and lactoferrin make active bowel inflammation unlikely. In children younger than 2 years and in those with atypical presentation immunological tests are required to exclude chronic granulomatous disease, common variable immune deficiency, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome and other immunodeficiency states. Increasing experience with MR enterography, the lack of exposure to radiation, and the utility of MRI in the evaluation of perianal CD, all favour this study over contrast meal and follow through for the radiological evaluation of the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy is showing promise as an adjunct in cases of diagnostic difficulty, but carries the risk of obstruction if the capsule becomes impacted at an occult area of narrowing. Lack of sensitivity of technetium leukocyte scintigraphy has largely consigned this test to being of historical interest only.

CLASSIFICATION

The Montreal classification of IBD classifies CD by virtue of age, location and behaviour (inflammatory, structuring or fistulating)[17]. It subdivides UC based on the extent and severity of the colitis. More detailed scoring systems have both prognostic and comparative value for research purposes. The paediatric CD activity index (PCDAI) is based on clinical parameters from recent history, examination findings, laboratory results, growth parameters and extra-intestinal manifestations[18]. The paediatric ulcerative colitis activity index (PUCAI) incorporates 6 clinical items and is therefore easy to use[19]. Any classification for CD can be particularly frustrating for the surgeon. The issue for the surgeon is the difference between macroscopic and microscopic disease. The danger of the classification system is that equal weight is given to asymptomatic microscopic disease, and the macroscopic disease which is actually causing the symptoms. Thus, for example, a patient may be labelled as having pan-intestinal CD when he is actually symptomatic from stricturing ileocaecal disease and merely has asymptomatic microscopic disease elsewhere. As with every classification system, its intrinsic usefulness is dependent on its clinical significance for decision making.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Ulcerative colitis

The medical approach to UC in childhood is dependent on the extent and severity of the colitis. Presentation with pan-colitis is twice as common (60%-80%) as adults[20], and for this reason steroid therapy is most often initiated. In less severe colitis, oral or rectal therapy with aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) derivatives would represent both first line and maintenance therapy after induction of remission. Oral ASA therapy may be combined with topical treatment but often the rectal route is unacceptable to the child. Steroids do not have a role in maintaining remission, and therefore thiopurines (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) are used as immunomodulators either alone or alongside 5-ASA. Thiopurines may take up to 10-14 wk to achieve therapeutic effect and are usually started alongside steroids for this reason. Infliximab should be considered in steroid-dependent UC, resistant to 5-ASA or thiopurines. Adalimumab may be substituted in patients who have lost response to or are intolerant of infliximab. Less commonly, cyclosporin or tacrolimus may be used in acute severe colitis as a bridging therapy before thiopurine efficacy. There is currently no evidence to support using methotrexate, antibiotics or probiotics for the induction or maintenance of remission in children. Similarly plasmapheresis remains controversial as a therapeutic option for severe childhood UC[21].

CD

Since CD has many phenotypic variants, medical therapeutic strategies are, to a certain extent, tailored both to disease location and to the severity of symptoms. Perianal CD (PACD) is discussed separately in this article since it is of particular interest to the surgeon, and only the broad principles of medical management of paediatric CD are discussed below. Both steroids and exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) are considered equally effective in inducing remission. There is no difference in efficacy of either elemental or polymeric formula feeds which both avoid the unpleasant side-effects of steroids and promote nutrition. Prolonged courses of EEN are difficult to sustain both due to taste and dietary boredom. In common with UC, remission is maintained with thiopurines which should be initiated at the onset of either dietary of steroid therapy. Unlike UC, methotrexate is effective in maintaining remission in cases of thiopurine toxicity. 5-ASA treatment cannot be recommended in the management of CD, both because of lack of paediatric data, and lack of efficacy in adults. Infliximab may be used as second line induction and maintenance therapy in relapsing CD where EEN or steroids are losing effect, or where side effects of steroids are intolerable[22,23]. Infliximab is controversial in the setting of the stricturing CD phenotype, with some studies suggesting lack of efficacy[24], and others favouring its use[25]. It is entirely possible that the distinction lies between fibrous and inflammatory strictures with lack of efficacy in the former group. It has been the author’s experience that acute obstructive symptoms may rapidly respond to steroid therapy suggesting a significant inflammatory component in the aetiology of symptoms. Second line biological therapy may be effective in case of either loss of effect of infliximab or intolerance. The rates of surgical treatment of IBD in the “biologic era” have recently received attention in the literature, suggesting that the overall incidence of surgery has declined in those with mild disease, but that the incidence of surgery is unchanged in patients with severe disease[26].

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF ULCERATIVE COLITIS

The objective in both elective and emergency surgical interventions for UC is the removal of the colon. The most common indication for colectomy is failure of medical therapy whether due to frequent disease activation with relative short periods of remission, or unacceptability of the side-effects of medical therapy. Inadequate disease control may also be reflected by reduced growth velocity, delayed puberty, inadequate nutrition, poor bone mineralisation and loss of time from school. Although some extra-intestinal features of UC are improved by surgery, primary sclerosing cholangitis and sacroiliitis are not[27]. Colonic cancer per se does not feature in the indications for colectomy in childhood since the quoted risk is 2% at 10 years, 8% at 20 years and 18% at 30 years[28]. However, a French study noted a 3-fold increased risk of neoplasia (including colon cancer 2/698) in paediatric onset IBD patients over a median follow up of 11.5 years[29], and the Porto IBD group noted a number of treatment-related malignancies (mainly lymphoma)[30]. Body image concerns are significant barriers to surgery for many children and careful support form psychologists and stoma therapists may be necessary for them to accept even a temporary stoma. Colectomy rates at five years from diagnosis range between 14%[31] and 24%[32,33] in children.

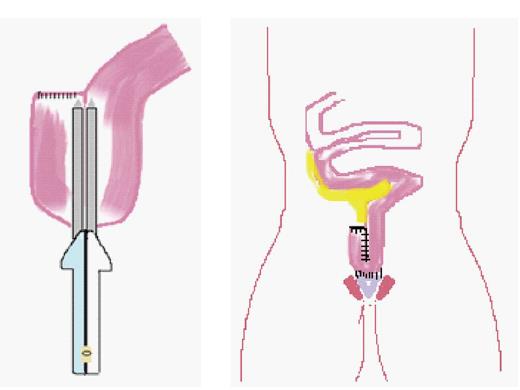

Reconstructive (continent) surgery for UC was transformed in 1978 by the development of the ileal pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) (see Figure 1) by Parks and Nicholls which is now the gold standard[34]. Since paediatric surgeons were at that time already familiar with straight ileoanal pull as an option for treatment of total colonic Hirschsprung’s disease[35], and also because of low patient numbers requiring colectomy for UC, they were generally late adopters of the IPAA. The most conservative approach for elective surgery is a 3-stage procedure performing total colectomy with end ileostomy, delaying completion proctectomy to the time of construction of IPAA, and covering this with a temporary ileostomy. Two-stage surgery either involves total colectomy and avoiding a covering ileostomy at the time of pouch formation (authors preference), or fashioning a primary pouch at the time of panproctocolectomy and covering this with an ileostomy. In the elective setting, total colectomy and end ileostomy was the most widely performed procedure in adult practice (guidelines American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons)[36], although panproctocolectomy, and primary pouch construction with covering ileostomy is rapidly gaining acceptance[37-39]. Clearly single stage surgery is feasible[40], but is associated with a higher risk of major complications such as anastomotic dehiscence, sepsis and late pouch failure[37]. Since the median number of pouch operations performed per year by United Kingdom paediatric surgeons specializing in IBD is 1 (range 0-4)[15], there is a natural tendency to opt for the most conservative elective operation and perform colectomy and end ileostomy. Children are usually transformed by this procedure and rapidly resume normal activity, including, most importantly, school attendance. Since significant symptoms from the retained rectum are infrequently encountered[41], the driver for restorative surgery is the child’s desire to lose the end ileostomy, which is usually counter-balanced by individual educational pressures and the child’s general sense of well-being.

Figure 1 Ileal pouch anal anastomosis being fashioned, stapling a small bowel J-pouch, and its anastomosis to the anus and sphincter complex.

The greater experience of IPAA within the adult sector and the fact that most children undergoing continent reconstruction will soon be transitioned into adult care, have prompted many surgeons to joint operate with adult colleagues at the time of pouch formation. Such cooperation both facilitates later transition and enables the sharing of technical expertise. Advances such as the double-stapled IPAA have been incorporated into paediatric practice with considerable reduction in operating time when compared with traditional hand-sewn IPAA. The complication rate has been shown to be unchanged and the functional performance of the reservoir marginally improved in the shift from the hand-sewn to the double-stapled anastomosis[42].

Large volume outcome data for IPAA within the paediatric sector are sparse with studies tending to compare the IPAA with straight pull through. A paediatric meta-analysis suggested a higher failure rate for straight (15%) over pouch (8%) pull through procedures, associated with both higher daily stool frequency and post-operative sepsis rates[39]. A multicentre analysis of 203 children undergoing straight (SIAA 112) and J pouch (JPAA 91) ileoanal anastomosis (mainly for UC) demonstrated significantly reduced daily stool frequency in the JPAA, although after 24 months the difference became less apparent (SIAA 8.4 vs JPAA 6.2)[43]. The mean daily defecation frequency 24 months after IPAA in a Finnish study was 3.3 ± 0.5, demonstrating that excellent short term functional results can be achieved in children[44].

Morbidity

The IPAA is associated with a high surgical complication rate. The Mayo clinic experience of intraoperative abandonment of IPAA (1789 cases) was 4.1%[45]. One large study including 151 children reported that one fifth of patients will have at least one complication in the first month after surgery[46]. This study focussed on pouchitis demonstrating a single episode in 48%, chronic refractory pouchitis in 7%, and pouch failure in 9%. The authors demonstrated that late diagnosed Crohns disease (15%) was an important determinant of poor outcome. In another paediatric series the complication rate was as high as 21/37 (57%); including stenosis of the IAA (2/37), pelvic abscess/sepsis (4/37), late fistula (3/37), early intestinal obstruction (7/37), late intestinal obstruction (11/37), pouch prolapse (1/37), wound complications 6/37, pouchitis (23/37), and recurrent pouchitis (13/37)[47]. Another paediatric study reported a high incidence (19%) of intestinal obstruction[48]. There is no reason to assume that the complication rates of IPAA in children should be different from those seen in adult practice where anastomotic dehiscence is observed in 5%-10%, pouch-vaginal fistula in 3%-16%, pouchitis in 24%-48%, and pouch failure at 5 years in 8.5%[38], as well as the risk of reduction in fertility in females, discussed in the next section. Long term follow up suggests overall cumulative pouch failure rates of 15% over 10-15 years. A proportion of these patients with outlet obstruction and low pouch capacity will be improved by abdominal salvage procedures[49]. There is very little experience in the paediatric surgical literature of revision pouch surgery which is a further strong argument for close links with high case load adult specialist units[15].

Ileorectal anastomosis

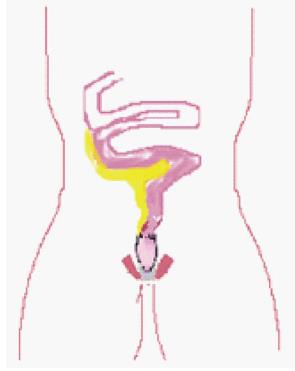

The option of ileorectal anastomosis (IRA) (Figure 2) for UC is rarely considered in childhood. Potential advantages include a reduced stool frequency with improved faecal continence[50], improved fertility in females[51], and a reduced likelihood of impaired sexual functioning due to nerve injury during the pelvic dissection. This has to be balanced with the need for regular endoscopic surveillance and the potential for failure of medical control of the residual disease in the rectum.

Figure 2 Straight ileo-rectal anastomosis.

The ultimate failure rate of IRA for UC is as high as 57%[52], but this does not argue against the procedure in females if time is gained for pregnancy before later restorative proctectomy. A meta-analysis has demonstrated that the rate of female infertility (15% in medically treated UC) rises to 48% after IPAA[53], although many of these “infertile” women could potentially achieve medically-assisted conception. Another systematic review demonstrated a more modest effect on infertility, with a rate of 12% before IPAA, and 26% thereafter (945 women in 7 studies). The same authors reported rates of sexual dysfunction (dyspareunia) in 8% preoperatively, compared with 25% after restorative surgery (419 women in 7 studies)[54]. One study looked at the effect of restorative proctectomy in childhood on later sexual function in adulthood concluding that rates of dysorgasmia and dyspareunia were not significantly different between girls undergoing surgical or medical management of UC. They authors also noted that sexual satisfaction was inversely correlated with faecal incontinence[55]. A study evaluating quality of life (QOL) after colectomy identified younger age at colectomy, diagnosis and survey to be associated with better QOL scores. The length of time post colectomy did not have any correlation with QOL[56].

ACUTE SEVERE COLITIS

The management of children presenting with acute severe colitis (ASC), identified by the requirement of intravenous steroid therapy, has been subject to little scrutiny in the literature. Cumulative colectomy rates in 99 children with ASC at discharge, 1 year, and 6 years, were 42%, 58% and 61% respectively[57]. Predictive factors significantly associated with corticosteroid failure include C-reactive protein, and the number of nocturnal stools on days 3 and 5. The PUCAI, Travis and Lindgren’s indices were strong predictors of failure of response to steroids[57]. In adult practice, the Travis criteria assessed on day 3 of steroid treatment indicate that a C-reactive protein > 45, and bowel action > 8 times per day, carry an 85% likelihood of subtotal colectomy during that admission[58]. The PUCAI has been promoted as a marker for failure of response to intravenous corticosteroids (day 3 > 45 points, and day 5 > 65-70 points) with a predictive accuracy of 85%-95%, allowing rapid introduction of second line medical therapies[57-59]. Early introduction of salvage medical therapies (cyclosporine, tacrolimus and infliximab) has reduced the emergency colectomy rate in ASC from 30%-70% to the current 10%-20%, with concomitant reduction in mortality[60]. Upper limits of normal colonic width in children with ASC should take age into consideration (4 cm < 11 years, and 6 cm in older children)[57]. Absolute indicators for surgery in the setting of unresponsive ASC include perforation and significant haemorrhage. Otherwise the risks, benefits and potential psychological morbidity of colectomy should be considered alongside salvage medical therapies.

The surgical procedure of choice is colectomy and end ileostomy preserving the rectal stump[60,61]. The options for managing the rectal stump include formation of a mucous fistula, division at the sacral promontory, or subcutaneous placement beneath the laparotomy wound. The presence of a mucus fistula is associated with mucoid discharge which may be unacceptable[41]. Although subcutaneous placement increases wound infection rates, the rate of pelvic sepsis is decreased when compared with division at the rectosigmoid junction[62,63].

LAPAROSCOPIC COLECTOMY AND POUCH ANAL ANASTOMOSIS

The adult sector now has a large experience of the application of laparoscopic approaches to surgery for UC. A meta-analysis comparing open and laparoscopic subtotal colectomy identified a conversion rate of 5%. Significant benefit was shown for laparoscopic surgery in terms of wound infection, intra-abdominal abscess, and length of stay[64]. Laparoscopic IPAA is increasingly being performed in adult IBD centres. The application of these techniques to paediatric practice has been slower. Diamond et al[65] identified a 7% conversion rate in 42 children undergoing subtotal colectomy. Fraser et al[66] compared overall morbidity seen in 44 children undergoing different variations on a theme of total colectomy (including 27 children with UC) noting an overall major complication rate of 43% unaffected by laparoscopic or open approaches. Linden et al[67] compared open (39) and laparoscopic-assisted (68) IPAA, demonstrating a significantly reduced incidence of small bowel obstruction at 1 year follow up in the laparoscopic group. Sheth et al[68] compared open (37) and laparoscopic (45) IPAA (including 56 children with UC) demonstrating comparable outcomes and surgical morbidity. Flores et al[69] compared open and laparoscopic colectomy in 32 consecutive patients finding significantly shorter lengths of stay in the laparoscopic group[69].

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT OF CD

The life time risk of surgery for CD is approximately 80%[70]. Indications for surgical management of children with CD include failure of medical therapy, growth failure despite full medical therapy, associated extra-intestinal manifestations (especially eye and joint pathology), and complications of the disease (fistula, obstruction, perforation, abscess formation, and bleeding). Timely surgical intervention has been demonstrated to improve height velocities in patients refractory to medical therapy[71,72]. Location of disease also has a significant bearing on the decision to operate or to persevere with medical management, since a local resection with primary anastomosis is less psychologically debilitating than a major colonic resection and possible permanent stoma.

Using the Paris classification (modification of the Montreal classification)[73], applied to 582 children on the EUROKIDS registry, 16% had isolated terminal ileal disease (± limited caecal disease), 27% had isolated colonic involvement, ileocolonic disease was seen in 53%, and 4% had a disease distribution at presentation localised to the upper gastrointestinal tract[74]. A radiological study suggested an increased propensity for left sided colitis in children compared with adults[75].

The author’s surgical perspective is of clear phenotypic subtypes (relating to macroscopic disease location), which greatly simplify decision making. Thus ileocaecal distribution including contiguous disease to the just beyond hepatic flexure (watershed of ileocolic arterial blood supply), and left sided colitis, are distinct and usually mutually exclusive phenotypes. Isolated proximal small bowel disease is rare in paediatric practice[76].

Resectional surgery

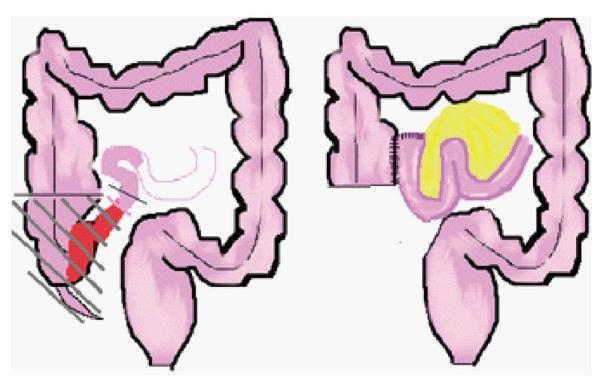

Requirement for surgical resection ranges from 20%-29% at 3 years, and 34%-50% at 5 years from diagnosis in paediatric practice[77-79]. The fundamental surgical consideration is localization of the macroscopic disease in accordance with one of the “five golden rules” of Alexander-Williams and Haynes[80], which may be paraphrased thus; “resect only symptomatic macroscopic disease”. Children with ileocolic disease (with colonic involvement proximal to the mid-transverse colon) are readily managed by right hemicolectomy and primary anastomosis with low associated morbidity[76] (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Ileocaecal resection for terminal ileal Crohn’s disease.

Debate continues regarding the management of colonic disease distal to the transverse colon, and whether this might break the golden rule of surgical conservatism. The phenotype associated with left sided colitis in childhood has been shown to relapse early following segmental resection[81], or develop significant complications from anastomotic failure after segmental resection[76]. An adult meta-analysis (448 patients) suggested that segmental resection was not associated with increased overall recurrence rates, complications, or need for a permanent stoma, but that time to recurrence was longer by 4.4 years in the subtotal resection group[82]. However, segmental resection for left sided colitis continues to be advocated by some surgeons, citing preservation of anorectal function and decreased post-operative symptoms[83]. Another study advocated segmental resection over subtotal colectomy and IRA, based on favourable clinical recurrence rates, reoperation rates and risk of permanent stoma requirement. Risk factors for recurrence/reoperation included both perianal CD and colocolic anastomosis, which implies that ileocolic anastomoses were included in the evaluation and thus that cases of right sided colitis were included in the evaluation[84]! A possible explanation for the difference between the paediatric and adult experience is that subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy was favoured in children compared to IRA in adults. Defunctioning the rectum in Crohn’s colitis is potentially therapeutic for associated CD within the retained rectum[85], but might predispose to later disuse proctitis. Prospects for restoration of continuity are limited, and the adolescent needs to know that the stoma may be permanent and that half of all patients will eventually come to proctectomy[86].

Disease recurrence

Recurrence following surgery in paediatric CD has received little attention in the paediatric surgical literature since transition to adult care has usually taken place before repeat surgery is required. A small paediatric series comprising 82 children undergoing surgery for CD concluded that early recurrence was associated with extensive colonic disease, long duration of symptoms (> 1 year) before surgery, and failure of medical therapy as underlying reason for surgery[72]. Another paediatric series found significantly earlier recurrence in children with colonic rather than ileocaecal disease. The same report also showed that high PCDAI scores were correlated with a shorter remission periods[87]. In a study of 1936 adult patients, surgical re-intervention was required in 25%-35% of all patients at 5 years and 40%-70% at 15 years[88]. The only patient-related factor consistently associated with early recurrence is smoking[89]. Studies analysing the influence of disease location on recurrence have shown no particular correlation, but the perforating/fistulating phenotype increases both clinical and surgical recurrence[89]. Studies looking at the influence of resection margins on disease recurrence have provided conflicting results. Most surgeons would advocate conservative resection to achieve margins free of macroscopic disease, with support from a randomized controlled trial[90]. There remains controversy surrounding the effect of anastomotic configuration (side to side vs end to end) on disease recurrence. The most recent meta-analysis suggested that side to side anastomosis was associated with reduced rate of recurrence[91], while an earlier meta-analysis and a randomized controlled trial failed to demonstrate any difference[92,93]. Recommendations on postoperative drug prophylaxis to prevent recurrence are lacking[89], but given the efficacy of thiopurine therapy in maintaining remission[94], there is a broad consensus in favour of maintaining this treatment in children after resectional surgery.

Anastomotic technique

The meta-analysis conducted by Simillis et al[92] concluded that side to side configuration was associated with fewer postoperative complications. The Cochrane review of ileocolic anastomoses concluded that stapled anastomosis were associated with fewer anastomotic leaks than handsewn, although subgroup analysis did not achieve significance in non-cancer patients[95]. Individual large volume cohort studies comparing stapled and hand sewn anastomoses in the treatment of CD have suggested a significant reduction in both anastomotic leak rate[96], and requirement for reoperation for anastomotic recurrence[97]. Lack of cross fertilization between adult and paediatric practice has undoubtedly been a factor in late adoption of stapling approaches to various anastomoses in paediatric IBD practice. Appropriate mentoring is essential in the adoption of any new technique, since use of an unfamiliar technique is associated with a higher incidence of complications including anastomotic failure[98].

Pre-operative optimisation

Risk factors associated with postoperative sepsis include poor nutritional status (where albumin < 30 g/L is a useful proxy), presence of abscess or fistula, preoperative steroids[99,100], and recurrent clinical exacerbations of CD[100]. Since the risk of a septic complication is additive with each of these risk factors[99], foreknowledge should prompt consideration of a temporary stoma rather than an anastomosis[100]. These considerations have fuelled the debate on preoperative optimization in patients with CD. To date there is little strong evidence supporting delaying surgery to allow for a period of pre-operative hyperalimentation by either enteral or parenteral routes[101]. However medical management of sepsis and percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal abscesses may reduce post-operative septic complications[101].

Strictureplasty

Repeated resectional surgery in CD is clearly associated with a risk of short bowel syndrome in adulthood. For this reason strictureplasty has become an established surgical approach with proven efficacy and safety in adult practice[102]. A meta-analysis (1112 patients) identified septic complications in 4% and a 5 year recurrence rate of 28%[103]. As has been seen elsewhere paediatric surgeons have been slow to adopt strictureplasty into their operative repertoire. A comparative study of strictureplasty (19), resection (13), and combined (8) procedures in children demonstrated that strictureplasty was associated with a significantly earlier recurrence rate[104]. However another paediatric group have successfully used strictureplasty in long segment stenosis without complication and with good symptom control[105].

Balloon dilatation for Crohn’s strictures

The evidence for balloon dilatation of strictures in Crohn’s Disease is limited to the adult literature only. One third of patients diagnosed with CD develop strictures within 10 years of diagnosis[106]. Dilatation is usually attempted to a diameter of 18-25 mm in gradual increments[107]. Complications include bleeding and perforation. Short term success rates are 86%-94%[107,108], which may be enhanced when used in conjunction with oral corticosteroids[109], or intralesional steroid injection[107]. Intervention-free success rates decline over time, with relapse rates quoted as 46% after a mean of 32 months. However one third of patients require no further treatment ten years after their first dilatation[107].

SPECIAL SITES

PACD

The management of PACD continues to pose a significant challenge to both gastroenterologist and surgeon, despite significant advances in understanding of the epidemiology and natural history, occurring alongside the development of new treatment modalities. As in other areas of paediatric IBD practice, there is a distinct lack of good quality evidence on which to base therapeutic strategy, and reliance is therefore placed on extrapolation from the adult literature, and from expert consensus.

The incidence of symptomatic PACD at presentation in a cohort of 145 children with CD in the Northwest of England was 25 (17%). The majority (80%) required some form of surgical intervention for their PACD. Paediatric studies suggest a wide range of incidence from 15% at initial presentation[110], to 62% over the course of their disease[111]. This wide disparity may reflect a degree of inattention (from either patient or doctor) to mild PACD in the setting of more debilitating disease at other sites, or reporting bias depending on medical or surgical authorship. PACD represents a spectrum of pathologies which can follow a relatively benign course, through to a locally aggressive process relentlessly progressing towards proctectomy. The presence of PACD has been associated with young age at presentation, ileal disease distribution and defective expression of neutrophil cytosolic factor (NCF4), again linking pathogenesis with defective invasive bacterial defensive mechanisms[112].

The most commonly used descriptive assessment of PACD is the Cardiff classification which reflects the severity of three components of the disease spectrum; ulceration, abscess/fistula and anal stricture. Additional information is given concerning associated anal disease (A), proximal intestinal CD location (P), and inflammatory activity in the perianal disease (D)[113]. The Parks classification can only be applied to fistulating PACD and is a precise anatomical description of the fistula track in relation to the sphincter complex (superficial, intersphincteric, transphincteric, suprasphincteric and extrasphincteric), remembering that there may be multiple separate fistulae to describe in this way[114]. More recently an attempt has been made to simplify the classification of fistulae into simple and complex disease based on anatomy of the fistula, and the presence or absence of abscesses, strictures, and of significant rectal disease[115]. The perianal CD activity index, abbreviated PACDAI for the purposes of this article to distinguish it from the paediatric CD activity index (PCDAI), enables quantitative assessment of treatment efficacy[116], and has largely superseded the earlier classification of Irvine[117]. The PACDAI has no quality of life component, unlike Irvine’s score in which two of the five categories reflect interference with social and sexual activity. Both scoring systems were derived for adult patients, but since the former has as its focus the pathology of PACD, it can be applied to paediatric practice. As with many medical scoring systems, the PACDAI assigns a weighted numeric value to each component of the clinical picture assuming that the derived cumulative total has a value in quantifying disease severity. The result is a cumbersome tool whose value is less in the overall score and more in the precise description of each component of PACD. The authors consider the differentiation of PACD into ulcerating, fistulating and stenosing disease (after Cardiff) to have prognostic significance in terms of the likelihood of proctectomy. Our experience is that ulcerating PACD is often difficult to control, and if progressive can result in the need for proctectomy. Others, like us, have also concluded that stenotic PACD is associated with an unfavourable prognosis[118].

Effective management of PACD requires close collaboration between gastroenterologist and surgeon with appropriate use of imaging techniques. Three essential principles guide management; the prompt identification and drainage of any septic focus, conservative surgery, and appropriate medical therapy. The locally destructive effects of abscess formation and often significant pain both mandate early surgical drainage. The impaired wound healing commonly seen in patients with CD, should make a surgeon think twice about embarking on extensive perianal surgery. Fistulotomy may be undertaken in simple PACD with extra-sphincteric or short low inter-sphicteric fistula tracks in medically well-controlled disease and in the absence of significant rectal disease. However most surgeons favour the use of non-cutting setons to control septic complications from fistulae, especially in complex PACD. Setons are extremely well tolerated and, after drainage of pus, represent the principal adjunctive surgical contribution to medical management. Antibiotics (metronidazole and ciprofloxacillin) are effective in controlling acute exacerbations of PACD[119], and together with maintenance immunosuppression using thiopurines (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) comprise the first line of medical management. Steroids have no place in the treatment of PACD[120].

Since its introduction to the medical armamentarium against CD in 1999[121], the chimeric anti-TNF monoclonal antibody infliximab has provided an effective second line of medical management in recalcitrant Crohn’s perianal fistulae. Paediatric studies have confirmed its efficacy in the management of PACD[122,123]. Before embarking upon such biological therapy, the exclusion of occult sepsis should be mandatory and pelvic MRI should be undertaken, both for this purpose, and to document the extent of PACD at the start of therapy[124]. Early optimism associated with infliximab has persisted into more recent paediatric reports of control of fistulating disease in 76% at 1 year[123], and 56% at 2 years[125]. This experience has translated into some advocating infliximab as first line therapy in children with fistulating PACD rather than the “step up” approach outlined above[126]. Whilst expert opinion is tending to favour combined use of setons and infliximab in the treatment of complex Crohn’s perianal fistulae[127], there is no consensus regarding timing of removal of the seton and subsequent duration of biological therapy, although there is general agreement that full therapy should continue for a year[94]. Some authors are reluctant to recommend discontinuation of infliximab therapy because of the high relapse rate of fistulating PACD[128]. Similarly, others prefer to emphasize tolerability and efficacy of a long-term indwelling seton in control of complex PACD[129].

Appropriate evaluation of PACD should include recent anatomical localization of active disease burden by endoscopy and contrast-, or MR-enteroclysis. Pelvic MRI should be undertaken prior to EUA and rectosigmoidoscopy, for reasons identified above and also as a guide to informed surgical consent. Abscesses pointing to the perianal skin should be drained externally. Pelvic abscesses can be effectively drained using the trans-rectal route in the hope of avoiding formation of an iatrogenic extra-sphincteric fistula. Horse-shoe abscesses represent a particular challenge and may be drained via a trans-anorectal route. If control cannot be achieved by effective internal drainage and intensive medical management including antibiotics, thiopurine immunosuppressive maintenance, and infliximab, then a defunctioning stoma accompanied by laying open of the post anal space together with seton insertion will be required to achieve control of sepsis and hopefully avoid proctectomy. More complex fistulating disease involving the vagina or urinary tract is rarely seen in paediatric practice, and will usually require a defunctioning stoma in the first instance. In this circumstance fistula eradication is only going to be successful if there is no significant inflammatory involvement of the anorectum apart from that associated with the fistula itself. In the absence of significant proctitis, rectal mucosal advancement flaps[130], and interposition techniques such as graciloplasty[131] have all been employed with limited success.

A defunctioning stoma may provide significant temporary relief in advanced ulcerating, fistulating or stenotic PACD (usually seen in advanced Crohn’s proctitis), but healing of perianal disease, if it occurs to any meaningful extent, is usually reversed on restoration of continuity. This approach often only delays eventual proctectomy, which is required within 8 years in 50% of patients with locally aggressive PACD[132].

Proctectomy is not the end of the surgical challenge in this situation, since healing of the resultant perineal wound is often the exception rather than the rule. The use of topical negative pressure dressings to control sepsis, and, where necessary, delayed application of transposition muscle/myocutaneous flaps, can result in an acceptable cosmetic result.

In recent years novel local treatments directed at the fistula track in PACD have included the use of the CO2 laser[133], fibrin glues[134], and fistula plugs[135]. Local injection of infliximab into the fistula track[136], and the delivery of adipose tissue-derived stem cells either by direct injection[137] or by incorporating them into fistula plugs are current research developments that are showing some promise.

Upper GI CD

Upper GI endoscopy is mandatory in the investigation of CD since inflammatory changes have been demonstrated in up to 40% of children[138]. The incidence of gastroduodenal CD was only 10% in a group of 196 children in whom gastroduodenoscopy was solely performed in children with suggestive symptoms. Most cases with upper GI involvement are therefore asymptomatic with respect to the gastroduodenal inflammatory changes[139]. Endoscopic and histological findings are variable and often non-specific[140]. Medical treatment is rarely directed at the gastroduodenal disease alone since symptomatic disease is usually present distally. If treatment is deemed necessary then proton-pump inhibitors should be included with standard first line treatment[140]. There is no body of literature describing surgical intervention in childhood. The benign outlook in children is not reflected in the adult literature which probably reflects the fact that the huge adult caseload allows rare cases of clinically significant macroscopic gastroduodenal disease to come to the fore. Yamamoto et al[141] describe 54 patients with gastroduodenal disease in whom 33 required surgery mainly for gastric outlet obstruction (16 bypass, 10 strictureplasty and 4 gastrectomy). One third required re-operation for recurrent obstruction or stomal ulceration.

NEW DEVELOPMENTS IN SURGERY IN CHILDREN WITH IBD

The low case volume in paediatric IBD surgery has led to this subspecialty service being late adapters of technological and other advances coming out of adult colorectal practice as has been argued frequently in this article. The benefits of collaborative practice may seem self-evident, but take considerable effort to accrue, given the artificial separation of adult and paediatric medicine. In concluding this review we consider the potential benefits to paediatric practice of accelerated recovery programmes which are now commonplace in adult units, and mechanisms that ensure continuity of care as adolescents with IBD reach the interface between paediatric and adult services.

ENHANCED RECOVERY AFTER SURGERY

The recent widespread adoption of fast-track protocols in adult colorectal surgery has led to reduction in length of hospital stay with concomitant cost-reduction[142-145]. Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols focus on drawing together preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative considerations, which might enhance recovery, into a cohesive care package designed to effect significant gains by delivering multiple small increments of improved care. Studies of ERAS application in major colonic resections predominantly for inflammatory bowel disease have demonstrated either comparable[146], or reduced morbidity[147]. These benefits remain to be confirmed in children, but a comparative study of “conventional management” of children undergoing resectional surgery for inflammatory bowel disease, and of young adults (less than 25 years old) undergoing matched procedures according to an ERAS protocol, has demonstrated a significant reduction in hospital stay in the ERAS group without increase in morbidity[148]. This matched cohort study lacks the power of a RCT, but strongly suggests that the gains obtained from accelerated recovery programmes can be translated into paediatric IBD surgical practice.

Laparoscopy is considered to be an area in which gains might be achieved in earlier recovery, reduced pain and improved cosmesis, and is an integral part of many ERAS protocols. Demonstrating significant benefit for laparoscopy in any area other than cosmesis is highly controversial. This however does not detract from its potential value within a highly structured care package.

TRANSITIONAL CARE

The unique problems that arise in children with IBD, and the models of delivery of care in children’s services probably both conspire to delay referral into the adult sector. However, a recent United Kingdom study of paediatric IBD services suggested that transitional care arrangements were well established in most tertiary centres, and indeed that shared care with adult surgeons was a feature of practice, especially in relation to ileoanal pouch surgery. This is probably explained both by the lack of exposure to IBD surgery in the training programmes of United Kingdom paediatric surgeons, and by the small case load even in the larger centres[15].

The fact that most children requiring colectomy and IPAA for UC are approaching the age at which transition into adult care is feasible, strengthens the argument for adult surgical involvement, since the ethics of undertaking surgery with a high complication rate and then transferring responsibility for follow up within a short time frame is certainly open to question. Furthermore case volume considerations, and the allocation of research funding and scarce health care resources, maximise the options available for the young patient with IBD to access the newest treatment when shared care is available.

Consensus guidelines issued jointly by the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization and the ESPGHAN[149], state that every adolescent should be included in a transitional care programme which is adapted to fit local paediatric and adult health care models, and that within the paediatric setting adolescents should be encouraged to take increasing responsibility for their treatment and visit the clinic at least once without their parents. Endoscopic interventions in children with IBD are performed under general anaesthesia and are largely diagnostic. Adult endoscopy is performed almost exclusively under sedation and is performed more frequently given the increasing emphasis on surveillance with duration of disease. Other details of care which enhance the perception that paediatric health care delivery is more child-friendly, include the emphasis on nutrition, growth, puberty and psychological well-being, including integrating health care into the educational needs of the child. These factors are therefore potential barriers to timely transition, which need to be overcome to ensure that each adolescent can access the full range of treatment options.

There are no research studies with confirm the suggested benefits of well-organized transition services in IBD[150]. However it is likely that the perceived benefits of structured transition programmes seen in other chronic paediatric conditions will translate into the setting of adolescent IBD[151].

P- Reviewer: Andersen NN, Bokemeyer B, Radmard AR S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN