Published online Jan 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.584

Peer-review started: May 20, 2014

First decision: June 27, 2014

Revised: August 4, 2014

Accepted: November 11, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

Published online: January 14, 2015

Processing time: 244 Days and 3.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the prophylactic efficacy of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) in combination with different nucleos(t)ide analogues.

METHODS: A total of 5333 hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients from the China Liver Transplant Registry database were enrolled between January 2000 and December 2009. Low-dose intramuscular (im) HBIG combined with one nucleos(t)ide analogue has been shown to be very cost-effective in recent reports. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) prophylactic outcomes were compared based on their posttransplant prophylactic protocols [group A (n = 4684): im HBIG plus lamivudine; group B (n = 491): im HBIG plus entecavir; group C (n = 158): im HBIG plus adefovir dipivoxil]. We compared the related baseline characteristics among the three groups, including the age, male sex, Meld score at the time of transplantation, Child-Pugh score at the time of transplantation, HCC, pre-transplantation hepatitis B e antigen positivity, pre-transplantation HBV deoxyribonucleic acid (HBV DNA) positivity, HBV DNA at the time of transplantation, pre-transplantation antiviral therapy, and the duration of antiviral therapy before transplantation of the patients. We also calculated the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates and HBV recurrence rates according to the different groups. All potential risk factors were analyzed using univariate and multivariate analyses.

RESULTS: The mean follow-up duration was 42.1 ± 30.3 mo. The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were lower in group A than in groups B (86.2% vs 94.4%, 76.9% vs 86.6%, 73.7% vs 82.4%, respectively, P < 0.001) and C (86.2% vs 92.5%, 76.9% vs 73.7%, 87.0% vs 81.6%, respectively, P < 0.001). The 1-, 3- and 5-year posttransplant HBV recurrence rates were significantly higher in group A than in group B (1.7% vs 0.5%, 3.5% vs 1.5%, 4.7% vs 1.5%, respectively, P = 0.023). No significant difference existed between groups A and C and between groups B and C with respect to the 1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates. Pretransplant hepatocellular carcinoma, high viral load and posttransplant prophylactic protocol (lamivudine and HBIG vs entecavir and HBIG) were associated with HBV recurrence.

CONCLUSION: Low-dose intramuscular HBIG in combination with a nucleos(t)ide analogue provides effective prophylaxis against posttransplant HBV recurrence, especially for HBIG plus entecavir.

Core tip: Little is known about which protocol has the optimal prophylactic effects against hepatitis B virus (HBV) recurrence. In this study, we used data from the China Liver Transplant Registry database to evaluate the long-term prophylactic efficacy of hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) in combination with different nucleos(t)ide analogues and determine the risk factors for HBV recurrence. This nationwide multicenter study demonstrated that low-dose intramuscular HBIG in combination with a nucleos(t)ide analogue provides effective prophylaxis against recurrent HBV infection posttransplantation at approximately 5% of the cost of conventional high-dose intravenous HBIG regimens. Among them, low-dose intramuscular HBIG combined with entecavir has better prophylactic efficacy than the combination of low-dose intramuscular HBIG and lamivudine.

- Citation: Shen S, Jiang L, Xiao GQ, Yan LN, Yang JY, Wen TF, Li B, Wang WT, Xu MQ, Wei YG. Prophylaxis against hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: A registry study. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(2): 584-592

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i2/584.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i2.584

Globally, chronic hepatitis B remains the leading cause of liver-related mortality and accounts for more than one million deaths per annum. Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related liver diseases account for approximately 78% of all adult liver transplant recipients[1]. In selected patients with end-stage HBV-related liver diseases, liver transplantation (LT) offers a life-saving treatment with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 70%-80%. However, the main problem in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive recipients is the risk of HBV recurrence posttransplantation, which may lead to rapid disease progression or even death[2,3].

Before the availability of antiviral prophylaxis, HBV-related liver disease was considered a relative contraindication for LT because of a high HBV recurrence rate (80%)[4]. In 1987, hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) became available and its long-term use reduced the 3-year actuarial risk of HBV reinfection from 74% to 36%[5]. However, HBIG monotherapy has several disadvantages, including high cost, inconvenient administration and adverse effects. Currently, HBIG monotherapy is seldom used for prophylaxis against HBV recurrence after LT. Lamivudine (LAM) was subsequently considered a potential prophylactic agent in LT because it is inexpensive and well tolerated. However, the initial enthusiasm was tempered by the realization that long-term LAM monotherapy is associated with drug resistance leading to increased HBV reinfection[6,7].

Compared with the monotherapy, combination therapy with LAM and high-dose intravenous (iv) HBIG has shown encouraging outcomes with an HBV recurrence rate of less than 10% in 1-2 years of follow-up[8]. However, the major limitation of this regimen is its high cost, and other factors, including inconvenient administration and unavailability of iv HBIG in some countries. In China, many centers accept the prophylactic protocol with LAM and low-dose intramuscular (im) HBIG due to the national conditions and unavailability of iv HBIG. With the introduction of new nucleos(t)ide analogues, such as adefovir dipivoxil (ADV), telbivudine and entecavir (ETV), some centers also chose the protocol with another nucleos(t)ide analogue and im HBIG to prevent HBV reinfection after LT.

Using data from the China Liver Transplant Registry database, the aim of this study was to evaluate the long-term prophylactic efficacy of HBIG in conjunction with different nucleos(t)ide analogues in China and identify the risk factors for posttransplant HBV recurrence.

Figure 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the cohort from the China Liver Transplant Registry database (https://http://www.cltr.org/). A total of 13273 adult HBsAg-positive patients were initially enrolled between January 2000 and December 2009; however, 168 patients with suspect data or with oral antiviral drug resistance before LT were excluded. After excluding 7727 patients who had incomplete data for analysis or did not use the prophylactic protocol with low-dose im HBIG and one nucleos(t)ide analogue, 5378 patients remained. We excluded an additional 45 patients with low-dose im HBIG and telbivudine because of the small size sample. Finally, 5333 patients were included. The patients were divided into the following three groups based on the nucleos(t)ide analogues used for the prophylaxis protocol: group A (n = 4684), which consisted of patients with HBIG and LAM; group B (n = 491), which consisted of those with HBIG and ETV; and group C (n = 158), which consisted of those with HBIG and ADV. The patients were monitored until September 2012 or until they were deceased, and their medical records were retrospectively reviewed. Living and deceased donations were voluntary and altruistic in all cases, approved by Ethics Committee of West China Hospital of Sichuan University, and in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was given by participants for their clinical records to be used in this study.

Prior to LT, patients with detectable serum HBV DNA received one nucleos(t)ide analogue daily, such as LAM, ETV or ADV, and the same nucleos(t)ide analogue was administered posttransplantation. HBIG was administered intramuscularly using a fixed dosing schedule, which consisted of 2000 IU of HBIG in the anhepatic phase, followed by 800 IU daily for the next 6 d, followed by weekly for 3 wk, and monthly thereafter.

Maintenance immunosuppression consisted of a triple-drug regimen that included tacrolimus or cyclosporine, mycophenolate and prednisone. Prednisone was generally discontinued within 3 to 6 mo after LT.

Prior to LT, viral markers including HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), hepatitis B e antibody, hepatitis B core antibody (HBcAb) and antibody to hepatitis C virus were routinely measured using standard commercial assays (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) as part of the Pre-LT workup for recipients and donors. Serum HBV DNA was determined using quantitative polymerase chain reaction method, with a limit of detection of 1000 copies/mL. After LT, liver function profiles were checked daily for the first week and then weekly for the first month, and monthly thereafter. Serum HBV markers were monitored weekly for the first month and monthly thereafter, and HBV DNA levels were evaluated monthly. HBV recurrence was defined as the reappearance of either HBsAg or HBV DNA in the serum. Liver biopsies were performed when clinically indicated by an elevation in serum liver enzyme levels.

SAS 9.2 statistical software was used to analyze the relevant data. Categorical data were presented as a number (percent) and compared using a χ2 test. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD, and analyzed using the Wilcoxon test. Survival curves and HBV recurrence were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences among ordered categories were determined by log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to test potential predictors of HBV recurrence after LT. Univariate results were reported as hazard ratios with 95%CI. The variables reaching statistical significance (P < 0.10) by univariate analysis were then included for multivariate analysis with proportional hazard regression. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the 5333 HBsAg-positive recipients using the prophylactic protocol with one nucleos(t)ide analogue and low-dose im HBIG. No differences existed among the recipients in groups A, B and C with respect to age, gender, pre-LT model for end-stage liver disease and pre-LT Child-Pugh score. However, group A had more recipients with positive HBV DNA and with high viral load (HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL) before transplantation than groups B and C. group C had more patients using antiviral therapy and longer duration of antiviral therapy before LT than groups A and B. group B had more patients combined with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) than groups A and C. In addition, both groups B and C had more patients with positive HBeAg before LT than group A.

| Group A | Group B | Group C | P value | |||

| A <-> B | A <-> C | B <-> C | ||||

| Number of patients | 4684 | 491 | 158 | - | - | - |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) (yr) | 48.2 ± 9.3 (19-76) | 48.3 ± 9.5 (19-73) | 48.4 ± 8 (26-71) | 0.892 | 0.998 | 0.956 |

| Male sex | 4136 (88.3) | 436 (88.8) | 142 (89.9) | 0.744 | 0.544 | 0.707 |

| MELD score at LT, mean ± SD (range) | 18.0 ± 9.5 (6-84) | 17.6 ± 10.1 (6-65) | 16.8 ± 9.2 (6-50) | 0.205 | 0.250 | 0.847 |

| Child-Pugh score at LT, mean ± SD (range) | 8.9 ± 2.5 (5-15) | 8.7 ± 2.8 (5-15) | 8.7 ± 2.7 (5-14) | 0.391 | 0.771 | 0.999 |

| With HCC | 2146 (45.8) | 251 (51.1) | 76 (48.1) | 0.025 | 0.571 | 0.509 |

| Pre-LT HBeAg positivity | 1169 (25.0) | 171 (34.8) | 58 (36.7) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.667 |

| Pre-LT HBV DNA positivity | 2248 (48.0) | 168 (34.2) | 62 (39.2) | < 0.001 | 0.030 | 0.251 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL at LT | 1024 (21.9) | 40 (8.1) | 17 (10.8) | < 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.313 |

| Pre-LT antiviral therapy | 2604 (55.6) | 272 (55.4) | 104 (65.8) | 0.934 | 0.011 | 0.021 |

| Duration of antiviral therapy before LT, mean ± SD (range) (d) | 233.4 ± 604.4 (1-7633) | 92.8 ± 299.3 (1-3280) | 347.1 ± 899.0 (2-7766) | 0.804 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| Number of donors | 4684 | 491 | 158 | - | - | - |

| Age, mean ± SD (range) (yr) | 28.8 ± 6.2 (18-62) | 29.1 ± 6.9 (19-61) | 29.3 ± 6.3 (20-51) | 0.997 | 0.700 | 0.737 |

| Male sex | 4495 (96.0) | 467 (95.1) | 147 (93.0) | 0.365 | 0.069 | 0.315 |

| Deceased donor | 4373 (93.4) | 424 (86.4) | 129 (81.7) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.147 |

| Living donor | 311 (6.6) | 67 (13.7) | 29 (18.3) | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.147 |

| BMI, mean ± SD (range) | 22.4 ± 2.7 (15.5-52.1) | 23.2 ± 2.7 (17.6-30.5) | 22.6 ± 2.9 (15.8-28.4) | 0.069 | 0.895 | 0.646 |

| HBsAb positivity | 606 (12.9) | 68 (13.8) | 27 (17.1) | 0.568 | 0.128 | 0.316 |

| HBcAb positivity | 160 (3.4) | 21 (4.3) | 2 (1.3) | 0.323 | 0.139 | 0.075 |

Table 1 also lists the baseline characteristics of the donors. The donors in the three groups had similar characteristics with respect to age, gender, body mass index, percentage of donors with serum positive HBsAb and HBcAb.

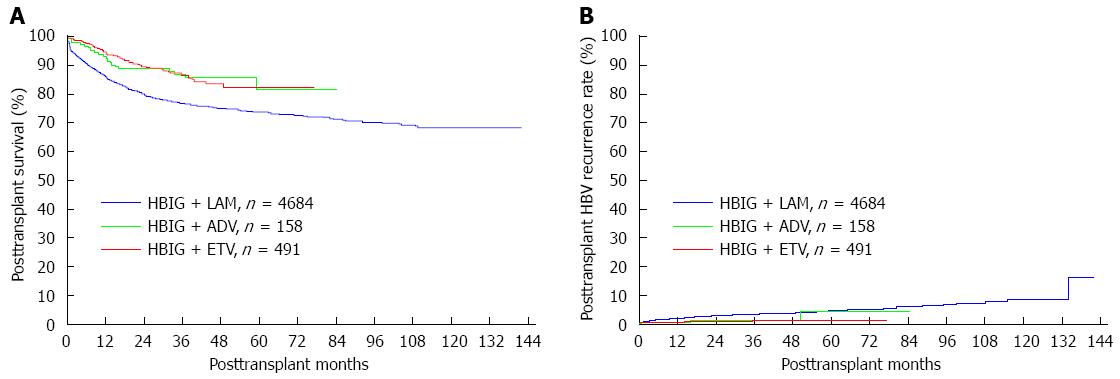

As shown in Table 2, 939 recipients died during the follow-up in group A, 57 in group B and 18 in group C. The survival curve for each group is shown in Figure 2A. The 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were significantly lower in group A than in groups B (86.2% vs 94.4%, 76.9% vs 86.6%, 73.7% vs 82.4%, respectively, P < 0.001) and C (86.2% vs 92.5%, 76.9% vs 87.0%, and 73.7% vs 81.6%, respectively, P < 0.001). In addition, the 1-, 3- and 5-year survival rates were 94.4%, 86.6% and 82.4%, respectively, in group B vs 92.5%, 87.0% and 81.6%, respectively, in group C (P = 0.137).

| Group A | Group B | Group C | P value | |||

| A <-> B | A <-> C | B <-> C | ||||

| Recipients (n) | 4684 | 491 | 158 | -- | -- | -- |

| Death during the follow-up (n) | 939 | 57 | 18 | -- | -- | -- |

| Cumulative survival rate | ||||||

| 1-yr | 86.2% | 94.4% | 92.5% | |||

| 3-yr | 76.9% | 86.6% | 87.0% | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.137 |

| 5-yr | 73.7% | 82.4% | 81.6% | |||

| Duration of follow-up, mean ± SD (range) (mo) | 45.8 ± 33.7 (0-141.8) | 30.2 ± 17.2 (0.1-77.1) | 35.1 ± 20.5 (0.2-84.2) | -- | -- | -- |

During the follow-up period, 179 patients experienced HBV recurrence in group A, 5 in group B and 3 in group C (Table 3). As shown in Figure 2B, the 1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates were significantly higher in group A than in group B (1.7% vs 0.5%, 3.5% vs 1.5%, 4.7% vs 1.5%, respectively, P = 0.023). No significant difference existed between groups A and C with respect to the 1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates (1.7% vs 0.7%, 3.5% vs 1.5%, 4.7% vs 4.4%, respectively, P = 0.060) and between groups B and C with respect to the 1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates (0.5% vs 0.7%, 1.5% vs 1.5%, 1.5% vs 4.4%, respectively, P = 0.234).

| Group A | Group B | Group C | P value | |||

| A <-> B | A <-> C | B <-> C | ||||

| Recipients (n) | 4684 | 491 | 158 | - | - | - |

| HBV recurrence during the follow-up (n) | 179 | 5 | 3 | - | - | - |

| Death in patients with HBV recurrence (n) | 47 | 2 | 1 | - | - | - |

| Cumulative HBV recurrence rate | ||||||

| 1-yr | 1.7% | 0.5% | 0.7% | |||

| 3-yr | 3.5% | 1.5% | 1.5% | 0.023 | 0.060 | 0.234 |

| 5-yr | 4.7% | 1.5% | 4.4% | |||

As shown in Table 4, pre-LT recipient with HCC, serum HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL, not using ETV before transplantation, post-LT HBV prophylactic protocol (LAM and HBIG vs ETV and HBIG), female donor and donor with negative serum HBsAb were significant risk factors for HBV recurrence by univariate analysis (P < 0.10). In multivariate analysis, pre-LT HCC, serum HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL and posttransplant HBV prophylactic protocol (LAM and HBIG vs ETV and HBIG) were found to be independent predictive factors for posttransplant HBV recurrence (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Factor | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 18-29 vs≥ 65 | 2.281 | 0.589-8.831 | 0.232 |

| 30-39 vs≥ 65 | 1.441 | 0.438-4.736 | 0.547 | |

| 40-49 vs≥ 65 | 1.910 | 0.603-6.057 | 0.272 | |

| 50-64 vs≥ 65 | 1.657 | 0.522-5.262 | 0.392 | |

| Gender | Male vs Female | 1.092 | 0.687-1.737 | 0.710 |

| Pre-LT MELD score | 6-9 vs 30-40 | 1.347 | 0.789-2.300 | 0.276 |

| 10-19 vs 30-40 | 1.226 | 0.767-1.958 | 0.395 | |

| 20-29 vs 30-40 | 1.034 | 0.613-1.744 | 0.899 | |

| Pre-LT Child-Pugh score | 5-6 vs 10-15 | 0.921 | 0.584-1.452 | 0.723 |

| 7-9 vs 10-15 | 1.029 | 0.710-1.492 | 0.879 | |

| Pre-LT with HCC | Yes vs No | 1.438 | 1.078-1.919 | 0.014 |

| Pre-LT HBeAg status | Positive vs Negative | 1.176 | 0.956-1.772 | 0.325 |

| Pre-LT serum HBV DNA level | ||||

| HBV DNA | Positive vs Negative | 1.185 | 0.805-1.743 | 0.389 |

| HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL | Yes vs No | 1.395 | 1.012-1.921 | 0.042 |

| Pre-LT antiviral therapy | ||||

| Using LAM | Yes vs No | 0.930 | 0.697-1.241 | 0.622 |

| Using ETV | Yes vs No | 0.133 | 0.019-0.949 | 0.044 |

| Using ADV | Yes vs No | 0.328 | 0.046-2.333 | 0.265 |

| Post-LT HBV prophylactic protocol | HBIG + LAM vs HBIG + ETV | 2.949 | 1.210-7.188 | 0.017 |

| HBIG + ADV vs HBIG + ETV | 1.714 | 0.410-7.171 | 0.461 | |

| Donor profiles | ||||

| Donor source | Living donor vs Deceased donor | 0.900 | 0.500-1.621 | 0.726 |

| Donor gender | Male vs Female | 0.564 | 0.298-1.067 | 0.078 |

| Donor HBsAb positivity | Positive vs Negative | 0.481 | 0.267-0.864 | 0.014 |

| Donor HBcAb positivity | Positive vs Negative | 1.598 | 0.786-3.247 | 0.195 |

| Factor | Hazard ratio | 95%CI | P value | |

| Pre-LT with HCC | Yes vs No | 1.718 | 1.243-2.375 | 0.001 |

| Pre-LT serum HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL | Yes vs No | 1.370 | 0.989-1.897 | 0.048 |

| Pre-LT using ETV | Yes vs No | 0.166 | 0.019-1.484 | 0.108 |

| Post-LT HBV prophylactic protocol | HBIG + LAM vs HBIG + ETV | 2.127 | 0.416-3.055 | 0.046 |

| Donor profiles | ||||

| Donor gender | Male vs Female | 0.632 | 0.156-1.144 | 0.201 |

| Donor HBsAb positivity | Positive vs Negative | 0.526 | 0.265-1.045 | 0.066 |

The cost for group A was approximately $4367 in the first year posttransplantation and $2741 yearly thereafter, and the corresponding figures were $5485 and $3860 for group B, and $4544 and $2918 for group C.

One goal of this study was to evaluate the prophylactic effects of low-dose im HBIG and different nucleos(t)ide analogues on posttransplant HBV recurrence in China. Presently, several nucleos(t)ide analogues are available for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Of these, ETV, which is a very potent anti-HBV selective guanosine analog, has higher efficacy than LAM or ADV in patients with chronic hepatitis B, therefore resulting in earlier and superior reduction in HBV DNA[9-11]. In addition, ETV is associated with a high genetic barrier to resistance that requires multiple mutations for resistance to emerge. In nucleoside-naive patients, the probability of developing resistance to ETV remained consistently low (< 1.2%) after 96 wk of therapy[12]. In view of the satisfactory outcomes of ETV in the non-transplant setting, ETV and HBIG may be a more effective prophylaxis protocol in transplant recipients than HBIG plus LAM or ADV. However, there are limited data on the use of ETV and HBIG in the transplant setting. To the best of our knowledge, there are three studies on patients receiving ETV and HBIG after LT[13-15]. One representative research was from Ueda et al[13] in 2013, in which ETV and HBIG resulted in no HBV recurrence during the median follow-up period of 25.1 mo in 26 patients. However, these studies were limited due to small size and short follow-up. It is difficult to draw a definite conclusion. Recently, Cholongitas et al[16] have published a systematic review about ETV and HBIG after LT. Their findings favor the use of HBIG and an hgbNA such as ETV instead of HBIG combined with LAM for prophylaxis against HBV recurrence after LT. In the nationwide multicenter study, combination prophylaxis with ETV and low-dose im HBIG resulted in 1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates of 0.5%, 1.5% and 1.5%, respectively, which were significantly lower than those in group B with LAM and low-dose im HBIG (1-, 3- and 5-year HBV recurrence rates of 1.7%, 3.5% and 4.7%, respectively, P = 0.023). Our result definitely reinforces the role of ETV in HBV prophylaxis after LT.

Another goal of this study was to identify the risk factors for posttransplant HBV recurrence. Three factors [pre-LT HCC, serum HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL and posttransplant HBV prophylactic protocol (LAM plus HBIG vs ETV plus HBIG)] were associated with posttransplant HBV recurrence in our study.

Currently, the role of HCC in posttransplant HBV recurrence remains unclear. Some studies have reported that pre-LT HCC is an important risk factor for HBV recurrence in patients undergoing transplantation[17,18], while others found no association between them[19,20]. In 2008, Faria et al[17] found that pre-LT HCC was associated with an increased risk of HBV reinfection after transplantation. Eleven of the 31 patients with HCC at the time of transplantation presented with HBV recurrence, and 3 of the 68 patients without HCC had HBV recurrence (P < 0.001). Recently, Xu et al[18] also reported a similar relationship between pre-LT HCC and post-LT HBV recurrence, one potential theoretical explanation for which may be that a large tumor burden on the explants may indicate the presence of extrahepatic, micrometastatic sites, which may serve as a source for HBV replication. The large cohort and long follow-up of this study are enough to evaluate the role of pre-LT HCC in posttransplant HBV recurrence, and our results further verify the close connection between pre-LT HCC and post-LT HBV reinfection. To reduce the impact of this risk factor, potent prophylactic protocols, such as ETV and low-dose im HBIG, may be recommended after LT in patients with pre-LT HCC.

As shown in the literature, positive HBV DNA or high pre-LT viral load has always been an important predictor of HBV reinfection posttransplantation[21-24]. Consistent with previous studies, the present data indicated that a pre-LT viral load greater than 105 copies/mL was an independent risk factor for hepatitis B relapse after LT. To reduce the impact of this risk factor, effective antiviral therapy is necessary. However, in practice the duration of antiviral therapy before LT varies among patients because it largely depends on the predictability of transplant timing. Therefore, the goal of reducing the HBV DNA level sufficiently prior to LT may not be achieved in every recipient.

As mentioned before, combination therapy with ETV and low-dose im HBIG has been proven to be a potent prophylactic protocol. In contrast, the regimen with LAM and low-dose im HBIG resulted in a higher rate of HBV recurrence. The relative weak prophylactic efficacy of LAM and HBIG compared with that of ETV and HBIG was also proven by both univariate and multivariate analyses. Therefore, ETV and HBIG may be considered an efficient therapy for the prevention of HBV recurrence after transplantation.

In addition, the predictive value of the pre-LT HBeAg status on HBV relapse posttransplantation remains controversial. Steinmüller et al[25] found that post-LT HBV recurrence rate was associated significantly with the preoperative HBeAg status. Patients in the positive HBeAg group showed a significantly higher recurrence rate than HBeAg-negative patients. In contrast, other studies reported negative results[24,26]. In this study, no significant difference was observed between the recipients with serum positive HBeAg and those with negative HBeAg (Table 4). It appears that preoperative HBeAg status is less valuable than the HBV DNA in predicting HBV recurrence.

The present study has several limitations, mainly based on its retrospective nature. We could not evaluate the prophylactic efficacy of the regimen with telbivudine and low-dose im HBIG because of the small size sample (45 cases), which could not reach a statistical significance. We also could not acquire detailed data on the post-transplant resistance of oral antiviral drugs. However, the large size (5333 cases) and long follow-up (mean, 42.1 ± 30.3 mo) of this current study has enabled accurate evaluation of prophylactic efficacy of different regimens and potential predictors of posttransplantation HBV recurrence.

In conclusion, this nationwide multicenter study demonstrated that low-dose im HBIG and one nucleos(t)ide analogue provides an effective prophylaxis against recurrent HBV infection posttransplantation at approximately 5% of the cost of conventional high-dose iv HBIG regimens. Among them, low-dose im HBIG combined with ETV has better prophylactic efficacy than the combination therapy with low-dose im HBIG and LAM. Thus, we suggest that ETV and low-dose HBIG should be considered an efficient therapy in our country instead of LAM and low-dose HBIG. In addition, three factors [pre-LT HCC, serum positive HBV DNA ≥ 105 copies/mL and posttransplant HBV prophylactic protocol (LAM and HBIG vs ETV and HBIG)] were associated with posttransplant HBV recurrence in our study.

The authors thank China Liver Transplant Registry database (https://http://www.cltr.org/) for providing the relevant data.

Hepatitis B virus (HBV)-related liver diseases account for approximately 78% of all adult liver transplant recipients. However, the main issue in hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive recipients is the risk of HBV recurrence posttransplantation, which may lead to rapid disease progression or even death. With the introduce of new nucleos(t)ide analogues, such as adefovir dipivoxil, telbivudine and entecavir (ETV), some centers also chose the protocol with another nucleos(t)ide analogue and intramuscular (im) hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) to prevent HBV reinfection after liver transplantation (LT).

Currently, little is known about which protocol has the optimal prophylactic effects against HBV recurrence. Authors use the data from China Liver Transplant Registry database to evaluate the long-term prophylactic efficacy of HBIG plus different nucleos(t)ide analogue and find the risk factors for HBV recurrence. Among them, low-dose intramuscular HBIG combined with ETV has better prophylactic effect than the combination therapy with low-dose intramuscular HBIG and lamivudine (LAM).

The results suggest that low-dose intramuscular HBIG combined with ETV has better prophylactic effect than the combination therapy with low-dose intramuscular HBIG and LAM.

Authors suggest that ETV plus low-dose HBIG should be considered an efficient therapy in their country instead of LAM and low-dose HBIG.

LT is the replacement of a diseased liver with part or all of a healthy liver from another person. In patients with end-stage HBV-related liver diseases, LT offers a life-saving treatment. However, the main issue in HBsAg-positive recipients is the risk of HBV recurrence posttransplantation, which may lead to rapid disease.

The paper reports on the results of the China Liver Transplant Registry on HBV prophylaxis in patients receiving liver transplantation. They conclude that a lower dose of HBIG plus adefovir or entecavir or lamivudine results in excellent treatment response, especially the combination HBIG/entecavir. The paper is well written and of highly clinical implications.

P- Reviewer: Herrero JI, Hilmi IA, Hori T, Schmidt HHJ, Sugawara Y S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Li X, Zheng Y, Liau A, Cai B, Ye D, Huang F, Sheng X, Ge F, Xuan L, Li S. Hepatitis B virus infections and risk factors among the general population in Anhui Province, China: an epidemiological study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Davies SE, Portmann BC, O’Grady JG, Aldis PM, Chaggar K, Alexander GJ, Williams R. Hepatic histological findings after transplantation for chronic hepatitis B virus infection, including a unique pattern of fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis. Hepatology. 1991;13:150-157. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Gane EJ, Patterson S, Strasser SI, McCaughan GW, Angus PW. Combination of lamivudine and adefovir without hepatitis B immune globulin is safe and effective prophylaxis against hepatitis B virus recurrence in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:268-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Todo S, Demetris AJ, Van Thiel D, Teperman L, Fung JJ, Starzl TE. Orthotopic liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B virus-related liver disease. Hepatology. 1991;13:619-626. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Samuel D, Muller R, Alexander G, Fassati L, Ducot B, Benhamou JP, Bismuth H. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842-1847. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Grellier L, Mutimer D, Ahmed M, Brown D, Burroughs AK, Rolles K, McMaster P, Beranek P, Kennedy F, Kibbler H. Lamivudine prophylaxis against reinfection in liver transplantation for hepatitis B cirrhosis. Lancet. 1996;348:1212-1215. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Perrillo RP, Wright T, Rakela J, Levy G, Schiff E, Gish R, Martin P, Dienstag J, Adams P, Dickson R. A multicenter United States-Canadian trial to assess lamivudine monotherapy before and after liver transplantation for chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2001;33:424-432. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Markowitz JS, Martin P, Conrad AJ, Markmann JF, Seu P, Yersiz H, Goss JA, Schmidt P, Pakrasi A, Artinian L. Prophylaxis against hepatitis B recurrence following liver transplantation using combination lamivudine and hepatitis B immune globulin. Hepatology. 1998;28:585-589. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Chang TT, Gish RG, de Man R, Gadano A, Sollano J, Chao YC, Lok AS, Han KH, Goodman Z, Zhu J. A comparison of entecavir and lamivudine for HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1001-1010. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lai CL, Shouval D, Lok AS, Chang TT, Cheinquer H, Goodman Z, DeHertogh D, Wilber R, Zink RC, Cross A. Entecavir versus lamivudine for patients with HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1011-1020. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Leung N, Peng CY, Hann HW, Sollano J, Lao-Tan J, Hsu CW, Lesmana L, Yuen MF, Jeffers L, Sherman M. Early hepatitis B virus DNA reduction in hepatitis B e antigen-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B: A randomized international study of entecavir versus adefovir. Hepatology. 2009;49:72-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Colonno RJ, Rose R, Baldick CJ, Levine S, Pokornowski K, Yu CF, Walsh A, Fang J, Hsu M, Mazzucco C. Entecavir resistance is rare in nucleoside naïve patients with hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2006;44:1656-1665. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ueda Y, Marusawa H, Kaido T, Ogura Y, Ogawa K, Yoshizawa A, Hata K, Fujimoto Y, Nishijima N, Chiba T. Efficacy and safety of prophylaxis with entecavir and hepatitis B immunoglobulin in preventing hepatitis B recurrence after living-donor liver transplantation. Hepatol Res. 2013;43:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jiménez-Pérez M, Sáez-Gómez AB, Mongil Poce L, Lozano-Rey JM, de la Cruz-Lombardo J, Rodrigo-López JM. Efficacy and safety of entecavir and/or tenofovir for prophylaxis and treatment of hepatitis B recurrence post-liver transplant. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:3167-3168. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Xi ZF, Xia Q, Zhang JJ, Chen XS, Han LZ, Wang X, Shen CH, Luo Y, Xin TY, Wang SY. The role of entecavir in preventing hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:321-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV. High genetic barrier nucleos(t)ide analogue(s) for prophylaxis from hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:353-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Faria LC, Gigou M, Roque-Afonso AM, Sebagh M, Roche B, Fallot G, Ferrari TC, Guettier C, Dussaix E, Castaing D. Hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with an increased risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1890-1899; quiz 2155. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Xu X, Tu Z, Wang B, Ling Q, Zhang L, Zhou L, Jiang G, Wu J, Zheng S. A novel model for evaluating the risk of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. Liver Int. 2011;31:1477-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marzano A, Gaia S, Ghisetti V, Carenzi S, Premoli A, Debernardi-Venon W, Alessandria C, Franchello A, Salizzoni M, Rizzetto M. Viral load at the time of liver transplantation and risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence. Liver Transpl. 2005;11:402-409. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Wong SN, Reddy KR, Keeffe EB, Han SH, Gaglio PJ, Perrillo RP, Tran TT, Pruett TL, Lok AS. Comparison of clinical outcomes in chronic hepatitis B liver transplant candidates with and without hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:334-342. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Wu TJ, Chen TC, Wang F, Chan KM, Soong RS, Chou HS, Lee WC, Yeh CT. Large fragment pre-S deletion and high viral load independently predict hepatitis B relapse after liver transplantation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Burra P, Germani G, Adam R, Karam V, Marzano A, Lampertico P, Salizzoni M, Filipponi F, Klempnauer JL, Castaing D. Liver transplantation for HBV-related cirrhosis in Europe: an ELTR study on evolution and outcomes. J Hepatol. 2013;58:287-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gane EJ, Angus PW, Strasser S, Crawford DH, Ring J, Jeffrey GP, McCaughan GW. Lamivudine plus low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent recurrent hepatitis B following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:931-937. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Chun J, Kim W, Kim BG, Lee KL, Suh KS, Yi NJ, Park KU, Kim YJ, Yoon JH, Lee HS. High viremia, prolonged Lamivudine therapy and recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma predict posttransplant hepatitis B recurrence. Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1649-1659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Steinmüller T, Seehofer D, Rayes N, Müller AR, Settmacher U, Jonas S, Neuhaus R, Berg T, Hopf U, Neuhaus P. Increasing applicability of liver transplantation for patients with hepatitis B-related liver disease. Hepatology. 2002;35:1528-1535. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Saab S, Yeganeh M, Nguyen K, Durazo F, Han S, Yersiz H, Farmer DG, Goldstein LI, Tong MJ, Busuttil RW. Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis B reinfection in hepatitis B surface antigen-positive patients after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:1525-1534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |