Published online May 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5393

Peer-review started: August 21, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 29, 2014

Accepted: January 5, 2015

Article in press: January 5, 2015

Published online: May 7, 2015

Processing time: 265 Days and 10.7 Hours

AIM: To compare the results of transvaginal cholecystectomy (TVC) and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CLC) for gallbladder disease.

METHODS: We performed a literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, MetaRegister of Controlled Trials, Chinese Medical Journal database and Wanfang Data for trials comparing outcomes between TVC and CLC. Data were extracted by two authors. Mean difference (MD), standardized mean difference (SMD), odds ratios and risk rate with 95%CIs were calculated using fixed- or random-effects models. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated with the χ2 test. The fixed-effects model was used in the absence of statistically significant heterogeneity. The random-effects model was chosen when heterogeneity was found.

RESULTS: There were 730 patients in nine controlled clinical trials. No significant difference was found regarding demographic characteristics (P > 0.5), including anesthetic risk score, age, body mass index, and abdominal surgical history between the TVC and CLC groups. Both groups had similar mortality, morbidity, and return to work after surgery. Patients in the TVC group had a lower pain score on postoperative day 1 (SMD: -0.957, 95%CI: -1.488 to -0.426, P < 0.001), needed less postoperative analgesic medication (SMD: -0.574, 95%CI: -0.807 to -0.341, P < 0.001) and stayed for a shorter time in hospital (MD: -1.004 d, 95%CI: -1.779 to 0.228, P = 0.011), but had longer operative time (MD: 17.307 min, 95%CI: 6.789 to 27.826, P = 0.001). TVC had no significant influence on postoperative sexual function and quality of life. Better cosmetic results and satisfaction were achieved in the TVC group.

CONCLUSION: TVC is safe and effective for gallbladder disease. However, vaginal injury might occur, and further trials are needed to compare TVC with CLC.

Core tip: Transvaginal cholecystectomy (TVC) is a new surgical method for gallbladder disease. We compared TVC and conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder disease. Patients in the TVC group had a lower pain score on postoperative day 1, needed less postoperative analgesic medication, stayed in hospital for a shorter time, but had longer operative time. TVC had no significant influence on postoperative sexual function and quality of life. Better cosmetic results and satisfaction were achieved in the TVC group. TVC is safe and effective for gallbladder disease.

-

Citation: Xu B, Xu B, Zheng WY, Ge HY, Wang LW, Song ZS, He B. Transvaginal cholecystectomy

vs conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy for gallbladder disease: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(17): 5393-5406 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i17/5393.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i17.5393

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has recently gained considerable attention as a potential new surgical method. NOTES techniques in animal models[1-9] have sparked interest in their feasibility in humans. From laboratory to clinic, Nau et al[10] has reported that transgastric NOTES is a safe alternative approach to accessing the peritoneal cavity in humans. Until now, the feasibility of NOTES has been reported in peritoneoscopy[11], appendectomy[12-14], colorectal resection[15-17], gastrectomy[18,19], hepatic cystectomy[20], splenectomy[21] and gynecological surgery[20]. Conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CLC) was often considered as a gold standard for benign gallbladder diseases, but now it has been challenged by NOTES and hybrid NOTES techniques.

Cholecystectomy has also been performed by pure or hybrid NOTES through transvaginal or transgastric access[22-25]. The most common approach of NOTES is transvaginal[26]; probably as the vagina appears to be the most practical and widely used site of specimen extraction and adjunct access[17]. In recent years, transvaginal cholecystectomy (TVC) has been reported widely[23,24,27-34]. The flexible endoscope makes the surgical field clear, without non-viewing angles during TVC, but it is difficult to maneuver. TVC may require a longer operative time and learning curve for young surgeons. A NOTES approach offers the potential of reducing pain and convalescence after intra-abdominal operations[29], while Noguera et al[24] showed no significant differences in postoperative pain between TVC and CLC. It is reported that better aesthetic effects can be achieved by TVC compared with CLC[27,31,32], although this still needs to be confirmed in future research. For patients who are concerned about the aesthetic benefits, TVC might be recommended. Some studies have reported that patients who have undergone TVC with no dyspareunia would recommend the procedure to their family and friends[35]. However, the choice of transvaginal access, with its possible effect on sex life and fertility, is not restricted entirely to women. Partners mostly oppose or dissuade against TVC because of the potential complications that threaten sexual activity and procreation[36]. Thus, there is continuing controversy regarding feasibility, safety and effectiveness of TVC, and further research is needed to ensure the safety and efficacy of TVC and dispel any misconceptions.

To date, many studies have reported experience of TVC and compared outcomes with those of CLC[23,24,27-34]. However, the results of these studies concerning short- and long-term outcomes and potential side effects were not consistent, and the studies had small sample sizes. The safety and effectiveness of TVC require further assessment[37], and whether TVC is superior to CLC needs to be strictly evaluated. This systematic review was designed to investigate the feasibility of TVC and establish whether TVC is superior to CLC by comparing short-term and long-term outcomes.

According to the proposed MOOSE (Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines[38] for meta-analyses, we performed a search of PubMed, EMBASE, Ovid, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, metaRegister of Controlled Trials and Chinese electronic databases (VIP, WanFang and CNKI) from their inception to May 24, 2013. Text key words were “hybrid cholecystectomy” or “Transvaginal cholecystectomy” or “NOTES transvaginal”. Reference lists of relevant retrieved articles were manually searched for additional studies. Language was restricted to English and Chinese. Results were limited to human studies.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) population: patients who needed to undergo cholecystectomy; (2) intervention: TVC; (3) control: CLC; (4) outcomes: morbidity, conversion rate, operative time, postoperative pain score, hospital stay, and postoperative dyspareunia; (5) types of studies: randomized controlled trials (RCTs), cohort study or case-control study; and (6) when two studies were published by the same institution or authors, either the one of higher quality according to modified Jadad Score[39] for RCTs, and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort studies, or the most recent article was included.

Studies were excluded from the analysis if: (1) it was impossible to extract the appropriate data; (2) there was considerable overlap between authors, institutes, or patients; (3) the measured outcomes were not clearly presented; (4) abstracts, letters, comments, editorials, expert opinions, reviews without original data, and case reports; (5) < 5 cases in the control or experimental groups; (6) articles were not in English or Chinese; (7) studies lacked a control group; or (8) animal studies.

Quality assessment was evaluated using modified Jadad Score[39] for the RCTs with a possible score of 0-7 (highest level of quality), and “good” was defined as a Jadad score of 4-7; and “poor” as a Jadad score of ≤ 3. The NOS was used to assess the quality of the other studies. Maximum score on this scale was 9. “Good” was defined as a total score of 7-9; “fair” as 4-6; and “poor” as < 4.

Two authors independently screened, identified and extracted the search findings. The titles and abstracts of the search findings were first screened for potentially eligible studies. Relevant full articles were obtained for detailed evaluation. When studies were reported by the same institution, either the study of better quality or the more recent publication was included. The potential variables assessed included first author, year of publication, study period, sample size, study type, patients’ baseline characteristics [e.g., age, body mass index (BMI) and previous operative history], operative methods, perioperative mortality and morbidity, postoperative complications, and short- and long-term outcomes. Study quality assessment was evaluated by Jadad score (for RCTs)[39] or NOS (for cohort and case-control studies). When differences occurred between the two reviewers, both of them re-reviewed the corresponding articles. The differences were resolved by consensus.

The meta-analysis was performed using Comprehensive Meta Analysis (version 2.2.064). Mean difference (MD), standardized mean difference (SMD), odds ratio (OR) and risk rate (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using fixed- or random-effects models to evaluate relevant clinical outcomes. Statistical heterogeneity was evaluated with the χ2 test (P < 0.100 considered to represent a significant difference) and the I2 statistic. I2≥ 50% indicated the presence of heterogeneity[40]. In the absence of statistically significant heterogeneity, the fixed-effects model was used to combine the results. When heterogeneity was confirmed, the random-effects model was used according to DerSimonian and Laird[41]. Data analysis was performed by comparing TVC with CLC. Funnel plots were introduced to evaluate potential publication bias, based on the postoperative morbidity. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

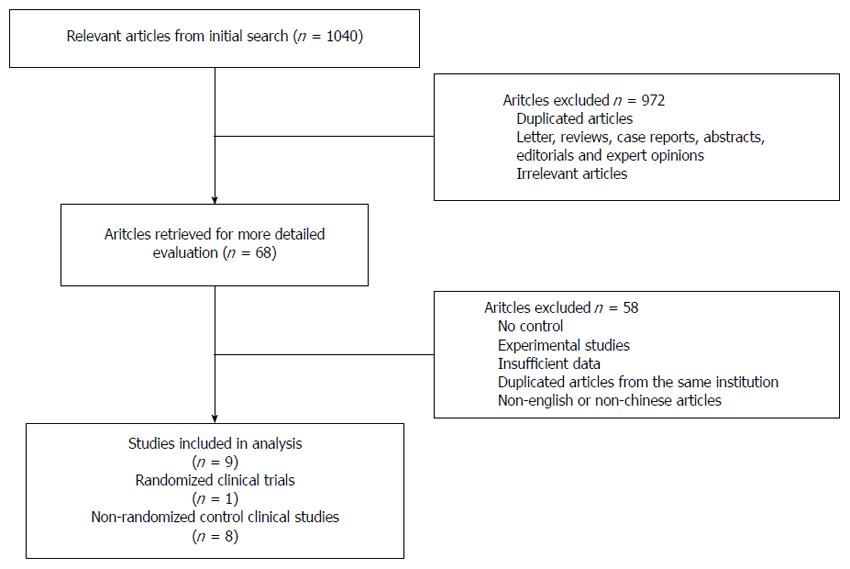

Our initial search yielded 1040 potential literature citations. If no information about comparing TVC and CLC for patients with gallbladder diseases was obtained in titles and abstracts, the articles were excluded. Nine hundred and seventy-two citations were excluded after scanning the titles and abstracts, leaving 68 citations for full-text assessment. After reviewing the full text, most studies were excluded largely because of a lack of control data. Bulian et al[23,27] reported their data from the same sample in two articles. They reported different results in the two papers, therefore, we chose the results we needed from both papers without reusing overlapping data. Finally, nine studies from 10 original articles comparing TVC with CLC were considered suitable for the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

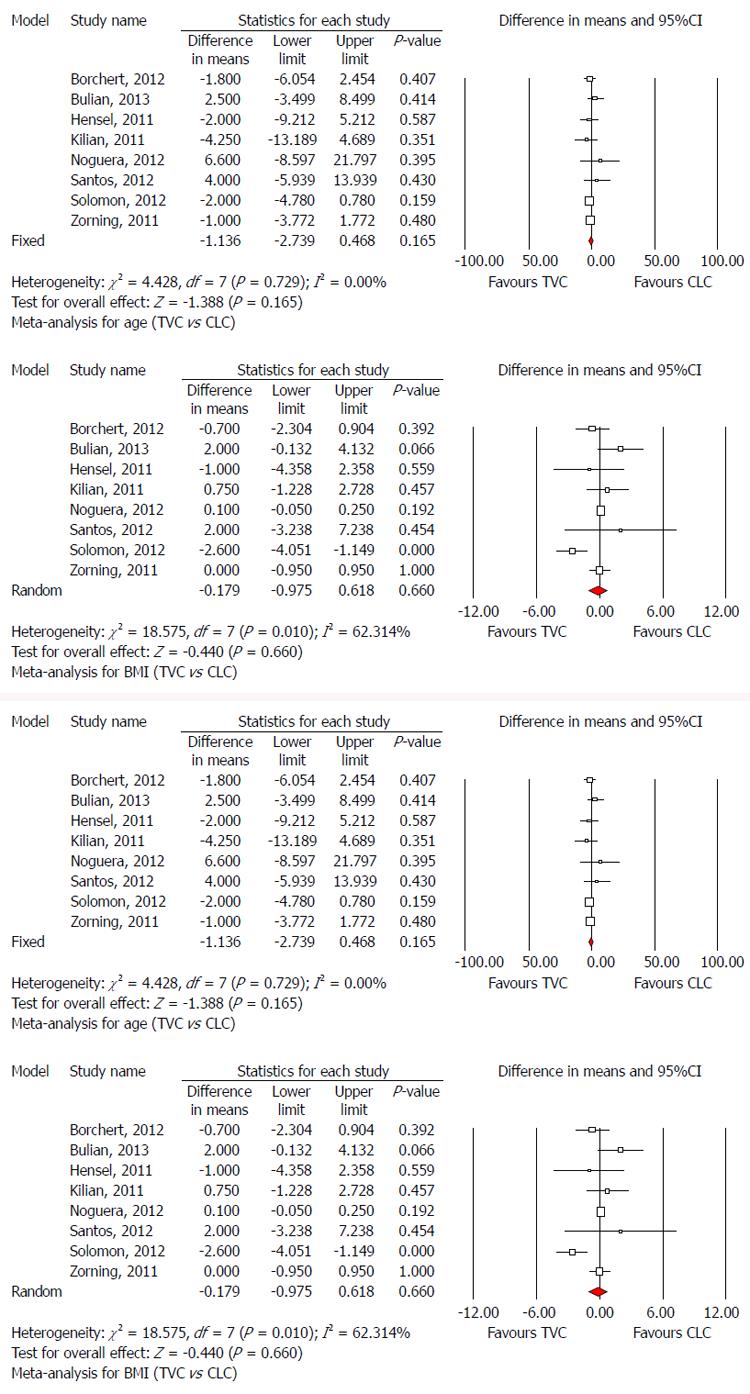

The nine included studies consisted of seven prospective[23,24,27-30,33,34] and two retrospective[31,32] studies. One of the seven prospective studies[24] was an RCT, and the others were prospective control studies. One study was conducted in China, two in the United States, one in Spain, and five in Germany. These studies included 730 patients with cholecystectomy recruited to either TVC (363, 49.73%) or CLC (367, 50.27%). The patient characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. There was no significant difference between the TVC and CLC groups with respect to age (MD: -1.136, 95%CI: -2.739 to 0.468, P = 0.165; Figure 2A), BMI (MD: -0.179, 95%CI: -0.975 to 0.618, P = 0.660; Figure 2B), and abdominal surgical history (OR: 0.90, 95%CI: 0.644 to 1.257, P = 0.537; Figure 2C).

| Ref. | Country | Publish Year | Study Period | Approach | Scopy | Follow up | Design | Quality assessment |

| Bulian et al[23,27] | Germany | 2013 | 2008-2010 | V + A | Rigid instruments | 1.04-3.14 yr | Prospective | Good |

| Solomon et al[28] | United States | 2012 | 2009-2010 | V + A | Flexible endoscope | 1 mo | Prospective | Fair |

| Santos et al[29] | United States | 2012 | 2009-2010 | V + A | Flexible endoscope | 3 mo | Prospective | Fair |

| Noguera et al[24] | Spain | 2012 | 2009-2010 | V + A | Flexible endoscope | 13-20 mo | RCT | Good |

| Borchert et al[30] | Germany | 2012 | 2007-2009 | V + A | Rigid instruments | 1 mo | Prospective | Good |

| Zornig et al[31] | Germany | 2011 | 2007-2009 | V + A | Rigid instruments | 3-10 mo | Retrospective | Good |

| Niu et al[32] | China | 2011 | 2009-2010 | V + A | Flexible endoscope | 2-11 mo | Retrospective | Good |

| Kilian et al[33] | Germany | 2011 | 2008-2009 | V + A | Rigid instruments | Null | Prospective | Fair |

| Hensel et al[34] | Germany | 2011 | 2010-2010 | V + A | Rigid instruments | 3 mo | Prospective | Fair |

| Ref. | Sample | ASA | Age (yr) | BMI (kg/m2) | Abdominal operative history | ||||

| TVC | CLC | TVC | CLC | TVC | CLC | ||||

| Bulian et al[23] | 50 | 50 | NSD | 46.3 | 48.8 | 26.7 | 28.7 | 46 | 28 |

| Bulian et al[27] | 50 | 50 | NSD | 46.3 | 48.8 | 26.7 | 28.7 | 46 | 28 |

| Solomon et al[28] | 14 | 11 | NA | 33.5 ± 3 | 35.5 ± 4.1 | 28.8 ± 1.5 | 31.4 ± 2.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Santos et al[29] | 7 | 7 | NSD | 38 ± 6 | 34 ± 12 | 29 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 28.6 | 42.8 |

| Noguera et al[24] | 20 | 20 | NSD | 40.6 | 47.2 | 27.5 | 27.4 | NA | NA |

| Borchert et al[30] | 84 | 81 | NSD | 52.9 ± 12.6 | 54.7 ± 15.2 | 27.1 ± 4.9 | 27.8 ± 5.6 | 65.5 | 63 |

| Zornig et al[31] | 100 | 100 | NA | 49 | 50 | 26 | 26 | 35 | 54 |

| Niu et al[32] | 43 | 48 | NA | 47.2 ± 9.6 | NA | 21.5 ± 6.2 | NA | NA | NA |

| Kilian et al[33] | 15 | 20 | NSD | 50.7 ± 12.4 | 55 ± 14 | 25.5 ± 2.5 | 24.7 ± 3.2 | 13.3 | 10 |

| Hensel et al[34] | 30 | 30 | NSD | 54 | 56 | 27 | 28 | 46.7 | 40 |

Mortality data were not available in six of nine studies[23,28,30-32,34]. The other three studies[24,29,33] included 42 TVC patients who showed that TVC was safe with zero mortality. No difference was identified between TVC and CLC regarding mortality due to zero mortality in both groups.

There was a similar incidence of complications among all studies, with low heterogeneity (P = 0.917, I2 = 0.000%). There was no significant difference in the overall complication rate among all the studies. Surgical complications were reported in 95 TVC cases, but not in 84 TVC cases used to evaluate other characteristics in the study of Borchert et al[30]. Niu et al[32] reported no complications in 43 TVC and 48 CLC cases. Because zero values cause problems with calculation of estimates and standard errors, 0.5 was added to each cell of the 2 × 2 table in the study of Niu et al[32]. So, 374 patients in nine studies underwent TVC. There were three cases of urinary bladder injury[29,23,30], two of bile duct injury[30,33], and one each of bleeding at the transvaginal access site[24], dislodged intrauterine contraceptive device[28], and wound infection[31], and only one case needed reoperation because of Douglas pouch abscess at 3 wk postoperatively[31]. Noguera et al[24] reported, during a mean follow-up period of 16 mo (range: 13-20 mo), no incision hernias in any TVC patient, which agreed with the long-term results reported by Bulian et al[27]. Cumulative analysis showed a trend for a lower morbidity rate in the TVC group, but there was no evidence of any significant difference in the incidence of complications between the two groups (TVC vs CLC): RR = 0.521 (95%CI: 0.245-1.110, P = 0.091; Figure 3).

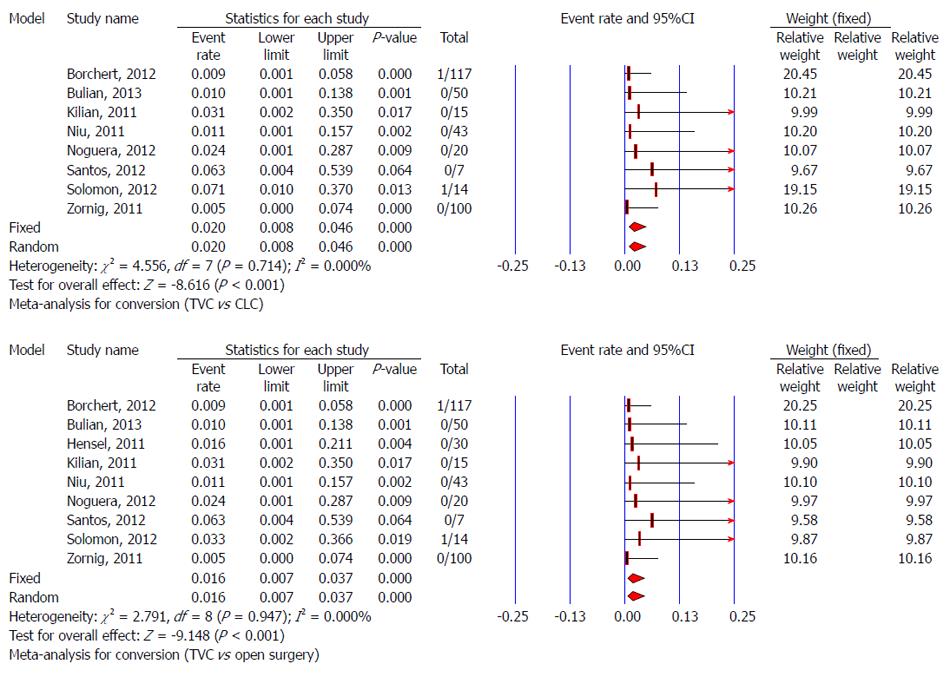

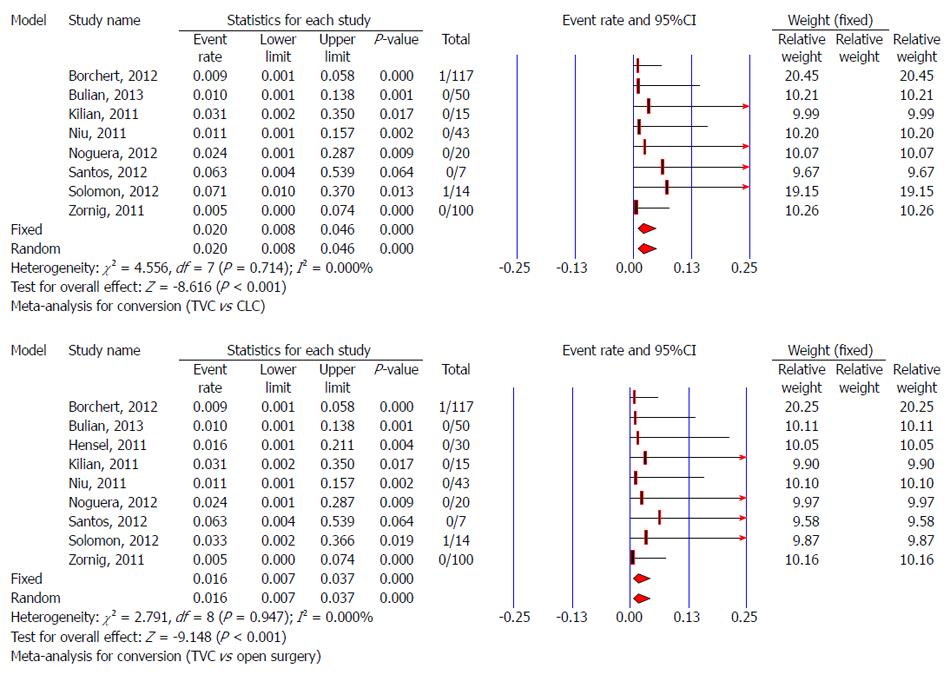

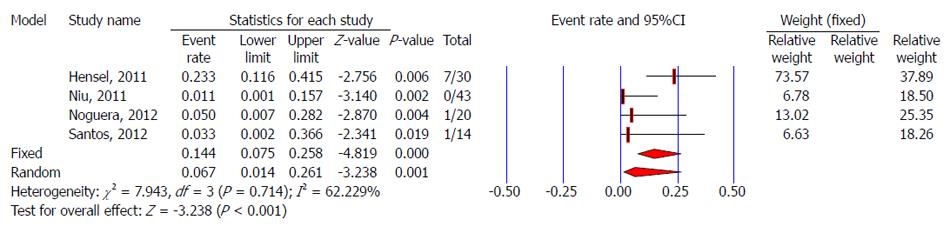

Data about conversion from TVC to CLC were not available in the study of Hensel et al[34]. One conversion to open cholecystectomy and one to CLC were reported in 117 TVC cases, but not in 84 TVC cases used to evaluate other characteristics in the study of Borchert et al[30]. So, there were 366 patients who underwent TVC in eight studies, and there were two cases that needed to convert to CLC due to adhesions[28,30,37]. The pooled conversion rate for TVC to CLC was 2% (95%CI: 0.8-4.6%). Test for heterogeneity was negative (P = 0.714, I2 = 0.000%), indicating low variation in the risk differences for conversion from TVC to CLC among studies. One of 296 cases switched to open surgery from TVC due to abdominal adhesions[30,37], so the pooled conversion rate for TVC to open surgery was 1.6% (95%CI: 0.7%-3.7%) without significant heterogeneity (P = 0.947, I2 = 0.00%) (Figure 4).

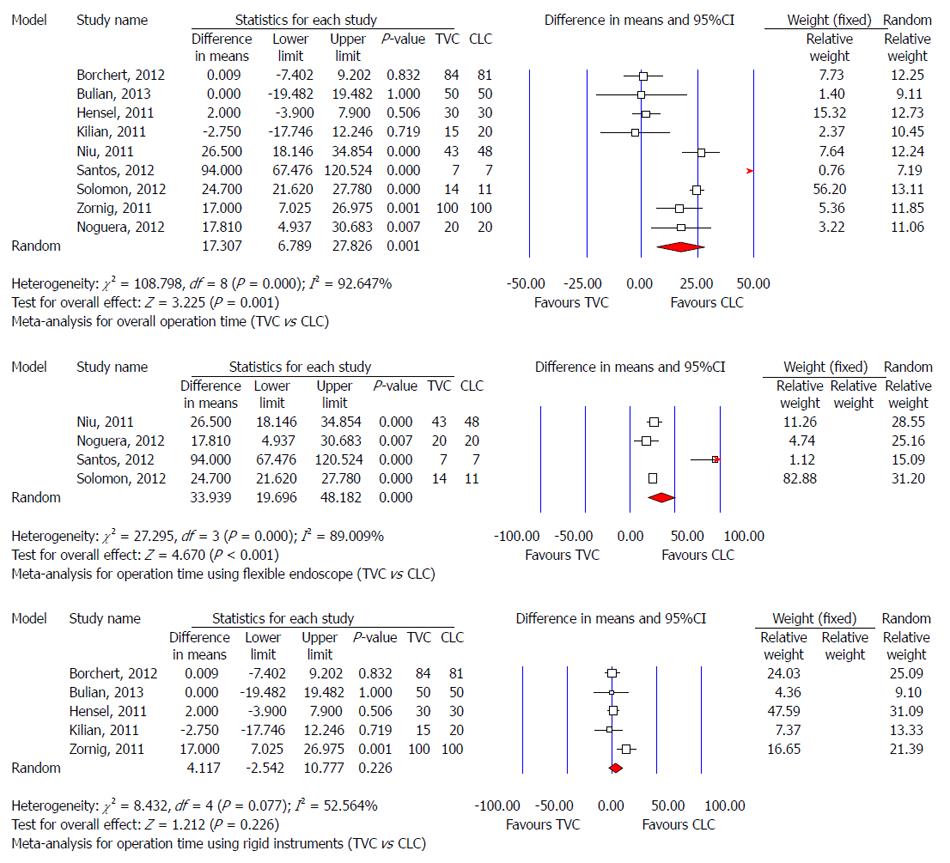

The forest plot showed two clusters: one with studies reporting a longer operative time for TVC, and the other showing no significant difference. Meta-analysis of nine studies using a random-effects model indicated that the operative time was significantly longer in the TVC group than the CLC group (MD: 17.307 min, 95%CI: 6.789-27.826, P = 0.001). However, this finding was associated with significant heterogeneity among studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 92.647) (Figure 5A). Nine studies were divided into two groups according to the type of endoscope used: flexible endoscope group[24,28,29,32] and rigid instruments group[23,30,31,33,34]. Subgroup analysis showed that the operative time for TVC using a flexible endoscope was longer (MD: 34 min, 95%CI: 20-48) compared with CLC (Figure 5B). However, there was no significant difference in operative time between TVC using rigid instruments and CLC (Figure 5C). Heterogeneity still existed in the flexible endoscope group (I2= 89%) and rigid instruments group (I2= 53%).

Data regarding negligible vaginal bleeding were not reported in five studies[23,29-31,33], and the other four studies reported the rate of negligible vaginal bleeding after TVC. No negligible vaginal bleeding occurred after TVC in two studies[28,32]. The pooled rate using a random-effects model for negligible vaginal bleeding after TVC was 6.7% (95%CI: 1.4%-26.1%) (Figure 6). It could be stopped spontaneously[34] or by direct compression with gauze[24].

TVC was successfully completed in the majority of cases. However, for some difficult cases, an additional abdominal 3- or 5-mm trocar was introduced. Five studies[23,24,29,31,33] showed a need to use an additional trocar to obtain clear exposure of the surgical field. The pooled rate (random-effects model) for the need for an additional trocar in TVC was 8.6% (95%CI: 3.2%-20.8%) (Figure 7).

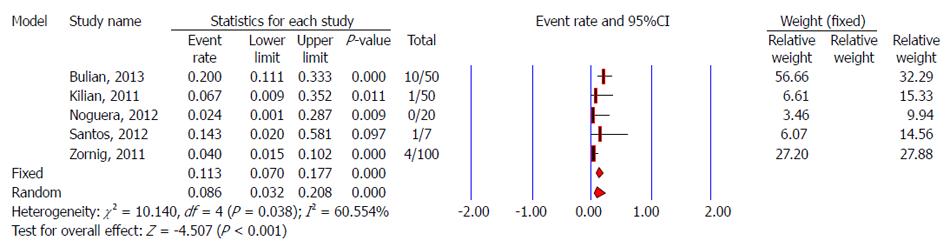

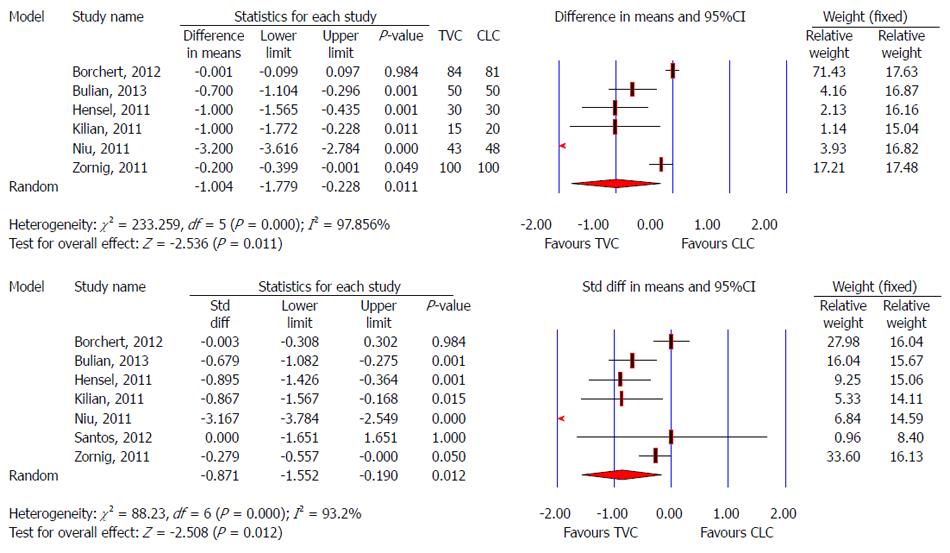

Four studies evaluated postoperative pain using a visual analog scale[24,29,30,32], four using a numeric rating scale[23,28,33,34], and one study had insufficient information about postoperative pain[31]. Different studies reported the pain score at different times. Niu et al[32] demonstrated a smaller postoperative pain score in the TVC group compared with the CLC group (P < 0.05), but a definite time point was not shown. Noguera et al[24] showed long-term results of postoperative pain and no significant differences were found between the TVC and CLC groups at 6 mo and 12 mo. Consumption of analgesics indirectly reflects the extent of postoperative pain. Meta-analysis showed a lower pain score on postoperative day 1 (SMD: -0.957, 95%CI: -1.488 to -0.426, P < 0.001) and less postoperative analgesic medication (SMD: -0.574, 95%CI: -0.807 to -0.341, P < 0.001) in the TVC group. Pooled analysis also indicated that there was no significant difference regarding pain score between the TVC and CLC groups at 2 d and 1 mo postoperatively (Figure 8).

Two of nine studies did not have sufficient information on postoperative hospital stay in the TVC or CLC group[24,28]. Santos et al[29] reported that there was no difference regarding postoperative hospital stay and outpatient surgery between the TVC and CLC groups. There was high heterogeneity among the studies regarding hospital stay (I2 > 90%). Four studies found a significant difference between the TVC and CLC groups; all favoring shorter stay in the former[23,31,33,34]. Meta-analysis using a random-effects model showed a significant difference between the two methods: MD was -1.004 d (95%CI: -1.779 to 0.228), favoring a shorter hospital stay in the TVC group (P = 0.011) (Figure 9).

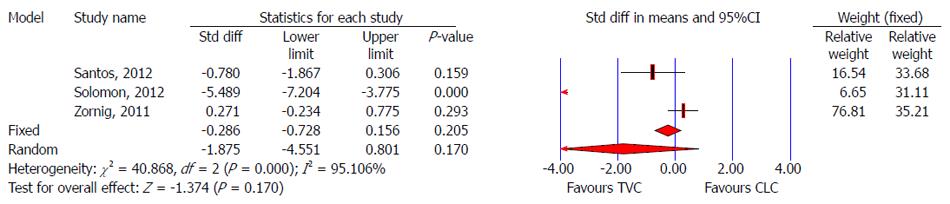

Three studies reported return to work after TVC[28,29,31]. Solomon et al[28] showed patients who underwent TVC experienced a significantly more rapid return to work, but the other two studies showed no significant difference between TVC and CLC. Pooled analysis also showed that there was no significant difference for return to work after surgery between the two groups (SMD: -1.875, 95%CI: -4.551 to 0.801, P = 0.170) (Figure 10).

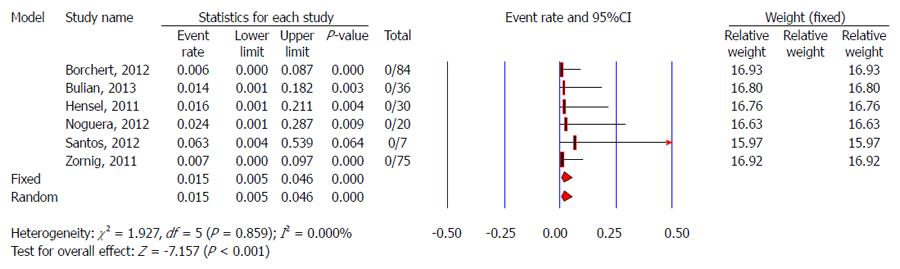

It was reported that TVC had no significant influence on postoperative sexual function[27,29,30]. Six studies reported postoperative dyspareunia, and no dyspareunia occurred in 252 cases[24,27,29-31,34]. Pooled predictive postoperative dyspareunia rate from a meta-analysis was 1.5% (95%CI: 0.5%-4.6%) (Figure 11).

Two of nine studies reported postoperative quality of life[29,30], and there was no difference between the TVC and CLC groups. Quality of life was assessed using the medical outcomes study item short from health survey (SF-36) and/or gastrointestinal quality of life (GIQoL) questionnaires. Santos et al[29] showed that the SF-36 Physical Component Score (PCS) and Mental Component Score (MCS) were similar between the TVC and CLC groups at 1 and 3 mo postoperatively. Similarly, there was no difference between the groups in the change from baseline of the PCS or MCS at 1 or 3 mo. Borchert et al[30] reported that there was no difference in any of the four domains of the GIQoL or eight SF-36 domains.

TVC had ideal cosmetic results with no visible scarring[27,31,32]. Zornig et al[31] reported that 10% of patients were not satisfied with their scars after CLC, but no similar complaints occurred in the TVC group. Niu et al[32] also supported better cosmetic results for TVC. Most TVC patients (96%[31]-100.0%[27]) were satisfied with TVC and its effectiveness and would recommend the technique.

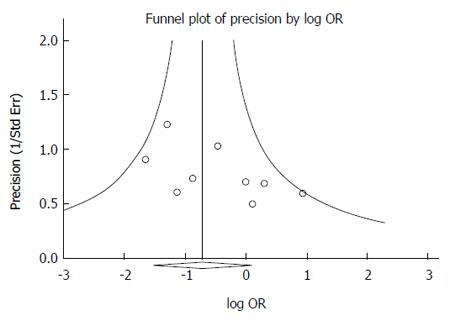

The funnel plot based on the incidence of postoperative morbidity is shown in Figure 12. Egger’s regression intercept was 1.357 (95%CI: -0.181 to 2.896, P = 0.075). Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation also showed no significant publication bias was identified (Z = 1.563, P = 0.117).

NOTES is considered to be a revolution in minimally invasive surgery and an alternative to traditional surgical approaches. However, it currently remains at a stage of clinical and experimental research. The transvaginal approach appears to be the most practical and widespread access for both pure and hybrid procedures (54% of reported NOTES cases)[17,42]. In human trials, transvaginal NOTES cholecystectomy is a novel procedure that is in a developmental stage. Much work is needed to verify its safety, confirm its efficacy, and resolve existing controversy. Our meta-analysis showed that TVC was feasible and safe for humans and it was not inferior to CLC.

TVC is technically feasible, but might take a longer time. Our meta-analysis based on similar baseline characteristics between TVC and CLC showed conversion to CLC from TVC was 2%. There was only one of 396 cases that switched to open surgery, due to abdominal adhesions. The pooled conversion rate to laparotomy was 1.6% in the TVC group and there was no significant difference compared with the CLC group. The above results partially demonstrated the feasibility of TVC. Technical problems regarding TVC include creating transvaginal access and maneuvering the endoscope. In initially performing TVC, gynecologists might be invited, because of their experience with performing colpotomy and subsequent closure. Maneuvering the endoscope is an important issue, which could affect the operative time in TVC. Results suggested a longer operative time of 34 min (95%CI: 20-48) in the TVC group when using a flexible endoscope, but not when using rigid instruments. So, the use of the endoscope was responsible for the increase in operative time during cholecystectomy. Heterogeneity still existed in the TVC flexible endoscope group, but this could be explained by different types of flexible endoscope[29], surgeons, and surgical experience[37]. For difficult cases due to severe abdominal adhesions and/or difficult exposure in gallbladder triangles, an additional trocar might be needed, which occurred in about 8.6% (95%CI: 3.2%-20.8%) of TVC cases. Vaginal bleeding might also be an issue in TVC. Current data showed that there was no severe intra- or postoperative vaginal bleeding. Sometimes, negligible vaginal bleeding occurred after TVC, with a pooled predictive rate of about 6.7% (95%CI: 1.4%-26.1%), but it could be stopped spontaneously or by direct compression with gauze.

Regarding short-term outcomes of TVC, our meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference in postoperative morbidity between TVC and CLC. We further proved the feasibility and safety of the TVC procedure. No mortality was seen among 714 NOTES procedures reported by Pollard et al[43]. Our study also showed that mortality in TVC was 0%. In 374 TVC cases, the most serious complications were bile duct injuries[30,33] in two cases, which were resolved by endoscopic bile duct stenting and conventional four-trocar laparoscopy. Only one case needed reoperation because of Douglas pouch abscess at 3 wk postoperatively[31]. Long-term follow-up showed no incisional hernias in any patient[24,27]. Funnel plot showed that there was no publication bias in the included studies, which improved the reliability of the pooled results. This meta-analysis indicated a trend for less morbidity in the TVC group, but no significant difference was identified. Pooled overall morbidity rate was 3.8%, and no significant difference was identified when compared with CLC (6.7%). Controversy exists with regard to postoperative pain and hospital stay between the two groups. Current studies showed no significant differences in postoperative pain, except for less pain in the TVC group on postoperative day 1. Less postoperative analgesic medication and shorter hospital stay were also identified in the TVC group. So, TVC might be a good alternative for uncomplicated gallbladder disease, according to the above short-term outcomes.

Many authors have reported that transvaginal surgery does not affect female sexual function[12,44], and even significantly improves sexual activity[45]. Linke et al[46] reported at 6 wk postoperatively that there were fewer dyspareunia symptoms than preoperatively. Our study showed no cases of postoperative dyspareunia[24,27,29-31,34], and the pooled predictive rate of postoperative dyspareunia based on 252 cases from six studies was about 1.5% (95%CI: 0.5%-4.6%). This rate should be further evaluated with large sample size RCTs. Postoperative normal quality of life and better cosmetic results and satisfaction were also achieved in the TVC group. Patients who underwent TVC would recommend it to their friends and family. No impact on quality of life and postoperative sexual function in TVC patients underlined this new procedure as a feasible approach in female patients. However, there was still a lack of comprehensive evaluation of quality of life, sexual function, cosmetic results, and patient satisfaction. Data are urgently needed from a large TVC sample regarding quality of life and sexual function, prospectively evaluated using an internationally recognized and comprehensive health-related quality of life and sexual function assessment.

The current study was based on seven prospective and two retrospective controlled clinical studies and only one study was a RCT. Our results need to be further confirmed with more RCTs. Blinding and randomization are sometimes difficult in medical practice, especially from an ethical viewpoint. Most studies included in our meta-analysis had considerable methodological limitations, including not justifying sample sizes based on calculation, poorly detailing the allocation, poorly blinding patients and assessors to the method of outcomes, and no adequate follow-up. These limitations should be considered in future design to improve the evidence. Our results might also have been affected by publication bias, heterogeneity between available studies, and imperfect and non-comprehensive retrieval. Some outcomes were assessed with small cohorts, which might have been affected by type II statistical errors. Considerable heterogeneity, small number of patients, and lack of unified evaluation criteria were pertaining to quality of life, sexual function, cosmetic benefits and patient satisfaction in our study. So, it might be inappropriate to use these results based on the current systematic analysis. Standard evaluation and definition of various clinical characteristics in future TVC clinical trials, especially concerning quality of life and postoperative sexual function, are necessary to decrease the heterogeneity and increase reliability of the merged results.

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that TVC was a feasible and safe procedure with a comparable risk of classic LC, which was not inferior to CLC in either effectiveness or safety due to less pain, shorter hospital stay and better cosmetic results and patient satisfaction. New TVC procedures still face several forms of bias, including patients, doctors and peer groups[30,47]. The rate of negligible vaginal bleeding was low, and it could be stopped spontaneously or by direct compression with gauze. No more severe intra- or postoperative vaginal bleeding was identified compared to CLC. Due to limitations in the current study, vaginal injury still needs to be carefully evaluated and further well-designed RCTs are required. Given the limitations identified in the current studies, both scientific and educational efforts are needed to prove the safety and efficacy of TVC. Well-designed RCTs with large samples need to be conducted, so that patients and doctors can make a reasonable decision together.

Conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy (CLC) is still considered as a gold standard for treatment of benign gallbladder diseases, but it has recently been challenged by transvaginal cholecystectomy (TVC). TVC is a novel technique for gallbladder disease, which offers the potential of reducing pain, shorter convalescence, and better aesthetic benefits compared to CLC.

Previous studies have different conclusions about the superiority of TVC to CLC. The results of these studies were not consistent. The safety and effectiveness of TVC require further assessment, and whether TVC is superior to CLC needs to be strictly evaluated.

Longer operative time was identified in the TVC group, but less postoperative pain, less postoperative analgesic medication, and shorter hospital stay were found. In addition, TVC had no significant influence on postoperative sexual function and quality of life, and better cosmetic results and patient satisfaction were achieved in the TVC group. TVC was not inferior to CLC, although vaginal injury needs to be carefully evaluated.

TVC is safe and effective for gallbladder disease, based on current available data.

TVC is a procedure in which the gallbladder is removed by endoscopy through the vagina.

The main core of the article is that TVC is an effective surgical therapy for gallbladder disease. The surgeon could choose TVC or CLC according to their relative merits, patients’ underlying disease and patients’ preference of TVC or CLC. The topic is very interesting, the results are applicable and the conclusions are valuable.

P- Reviewer: Bencini L, Young S S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: O’Neill M E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Bazzi WM, Stroup SP, Cohen SA, Sisul DM, Liss MA, Masterson JH, Kopp RP, Gudeman SR, Leeflang E, Palazzi KL. Comparison of transrectal and transvaginal hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery partial nephrectomy in the porcine model. Urology. 2013;82:84-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Vieira JP, Linhares MM, Caetano EM, Moura RM, Asseituno V, Fuzyi R, Girão MJ, Ruano JM, Goldenberg A, de Jesus L Filho G. Evaluation of the clinical and inflammatory responses in exclusively NOTES transvaginal cholecystectomy versus laparoscopic routes: an experimental study in swine. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3232-3244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Liu BR, Kong LJ, Song JT, Liu W, Yu H, Dou QF. Feasibility and safety of functional cholecystectomy by pure NOTES: a pilot animal study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:740-745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Córdova H, Guarner-Argente C, Martínez-Pallí G, Navarro R, Rodríguez-D’Jesús A, Rodríguez de Miguel C, Beltrán M, Martínez-Zamora MÀ, Comas J, Lacy AM. Gastric emptying is delayed in transgastric NOTES: a randomized study in swine. J Surg Res. 2012;174:e61-e67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bernhardt J, Köhler P, Rieber F, Diederich M, Schneider-Koriath S, Steffen H, Ludwig K, Lamadé W. Pure NOTES sigmoid resection in an animal survival model. Endoscopy. 2012;44:265-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zheng Y, Wang D, Kong X, Chen D, Wu R, Yang L, Yu E, Zheng C, Li Z. Initial experience from the transgastric endoscopic peritoneoscopy and biopsy: a stepwise approach from the laboratory to clinical application. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:888-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Voermans RP, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Bemelman WA, Fockens P. Hybrid NOTES transgastric cholecystectomy with reliable gastric closure: an animal survival study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:728-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sohn DK, Jeong SY, Park JW, Kim JS, Hwang JH, Kim DW, Kang SB, Oh JH. Comparative study of NOTES rectosigmoidectomy in a swine model: E-NOTES vs. P-NOTES. Endoscopy. 2011;43:526-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Earle DB, Romanelli JR, McLawhorn T, Omotosho P, Wu P, Rossini C, Swayze H, Desilets DJ. Prosthetic mesh contamination during NOTES(®) transgastric hernia repair: a randomized controlled trial with swine explants. Hernia. 2012;16:689-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nau P, Ellison EC, Muscarella P, Mikami D, Narula VK, Needleman B, Melvin WS, Hazey JW. A review of 130 humans enrolled in transgastric NOTES protocols at a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1004-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Noguera JF, Cuadrado A, Sánchez-Margallo FM, Dolz C, Asencio JM, Olea JM, Morales R, Lozano L, Vicens JC. Emergency transvaginal hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery. Endoscopy. 2011;43:442-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Solomon D, Lentz R, Duffy AJ, Bell RL, Roberts KE. Female sexual function after pure transvaginal appendectomy: a cohort study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:183-186; discussion 186-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R, Senthilnathan P, Prasad M. Transvaginal endoscopic appendectomy in humans: a unique approach to NOTES--world’s first report. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1343-1347. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Park PO, Bergström M. Transgastric peritoneoscopy and appendectomy: thoughts on our first experience in humans. Endoscopy. 2010;42:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tarantino I, Linke GR, Lange J, Siercks I, Warschkow R, Zerz A. Transvaginal rigid-hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery technique for anterior resection treatment of diverticulitis: a feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3034-3042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leroy J, Barry BD, Melani A, Mutter D, Marescaux J. No-scar transanal total mesorectal excision: the last step to pure NOTES for colorectal surgery. JAMA Surg. 2013;148:226-230; discussion 231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 133] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sanchez JE, Marcet JE. Colorectal natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) and transvaginal/transrectal specimen extraction. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17 Suppl 1:S69-S73. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cho WY, Kim YJ, Cho JY, Bok GH, Jin SY, Lee TH, Kim HG, Kim JO, Lee JS. Hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery: endoscopic full-thickness resection of early gastric cancer and laparoscopic regional lymph node dissection--14 human cases. Endoscopy. 2011;43:134-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ramos AC, Zundel N, Neto MG, Maalouf M. Human hybrid NOTES transvaginal sleeve gastrectomy: initial experience. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2008;4:660-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zorron R, Palanivelu C, Galvão Neto MP, Ramos A, Salinas G, Burghardt J, DeCarli L, Henrique Sousa L, Forgione A, Pugliese R. International multicenter trial on clinical natural orifice surgery--NOTES IMTN study: preliminary results of 362 patients. Surg Innov. 2010;17:142-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Targarona EM, Gomez C, Rovira R, Pernas JC, Balague C, Guarner-Argente C, Sainz S, Trias M. NOTES-assisted transvaginal splenectomy: the next step in the minimally invasive approach to the spleen. Surg Innov. 2009;16:218-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Satgunam S, Miedema B, Whang S, Thaler K. Transvaginal cholecystectomy without laparoscopic support using prototype flexible endoscopic instruments in a porcine model. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2331-2338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bulian DR, Trump L, Knuth J, Siegel R, Sauerwald A, Ströhlein MA, Heiss MM. Less pain after transvaginal/transumbilical cholecystectomy than after the classical laparoscopic technique: short-term results of a matched-cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:580-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Noguera JF, Cuadrado A, Dolz C, Olea JM, García JC. Prospective randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and hybrid natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) (NCT00835250). Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3435-3441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Salinas G, Saavedra L, Agurto H, Quispe R, Ramírez E, Grande J, Tamayo J, Sánchez V, Málaga D, Marks JM. Early experience in human hybrid transgastric and transvaginal endoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1092-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Clark MP, Qayed ES, Kooby DA, Maithel SK, Willingham FF. Natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery in humans: a review. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012;2012:189296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Bulian DR, Trump L, Knuth J, Cerasani N, Heiss MM. Long-term results of transvaginal/transumbilical versus classical laparoscopic cholecystectomy--an analysis of 88 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:571-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Solomon D, Shariff AH, Silasi DA, Duffy AJ, Bell RL, Roberts KE. Transvaginal cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus four-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2823-2827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Santos BF, Teitelbaum EN, Arafat FO, Milad MP, Soper NJ, Hungness ES. Comparison of short-term outcomes between transvaginal hybrid NOTES cholecystectomy and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3058-3066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Borchert D, Federlein M, Rückbeil O, Burghardt J, Fritze F, Gellert K. Prospective evaluation of transvaginal assisted cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:3597-3604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Zornig C, Siemssen L, Emmermann A, Alm M, von Waldenfels HA, Felixmüller C, Mofid H. NOTES cholecystectomy: matched-pair analysis comparing the transvaginal hybrid and conventional laparoscopic techniques in a series of 216 patients. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1822-1826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Niu J, Song W, Yan M, Fan W, Niu W, Liu E, Peng C, Lin P, Li P, Khan AQ. Transvaginal laparoscopically assisted endoscopic cholecystectomy: preliminary clinical results for a series of 43 cases in China. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1281-1286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kilian M, Raue W, Menenakos C, Wassersleben B, Hartmann J. Transvaginal-hybrid vs. single-port-access vs. ‘conventional’ laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective observational study. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:709-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hensel M, Schernikau U, Schmidt A, Arlt G. Surgical outcome and midterm follow-up after transvaginal NOTES hybrid cholecystectomy: analysis of a prospective clinical series. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2011;21:101-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tsin DA, Castro-Perez R, Davila MR, Davila F. Postoperative patient attitudes and perceptions of transvaginal cholecystectomy. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2010;20:119-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Kobiela J, Stefaniak T, Dobrowolski S, Makarewicz W, Lachiński AJ, Sledziński Z. Transvaginal NOTES cholecystectomy in my partner? No way! Wideochir Inne Tech Malo Inwazyjne. 2011;6:236-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Federlein M, Borchert D, Müller V, Atas Y, Fritze F, Burghardt J, Elling D, Gellert K. Transvaginal video-assisted cholecystectomy in clinical practice. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2444-2452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14425] [Cited by in RCA: 16803] [Article Influence: 672.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Bañares R, Albillos A, Rincón D, Alonso S, González M, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, Salcedo M, Molinero LM. Endoscopic treatment versus endoscopic plus pharmacologic treatment for acute variceal bleeding: a meta-analysis. Hepatology. 2002;35:609-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 277] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 46553] [Article Influence: 2116.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 41. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 30428] [Article Influence: 780.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Moris DN, Bramis KJ, Mantonakis EI, Papalampros EL, Petrou AS, Papalampros AE. Surgery via natural orifices in human beings: yesterday, today, tomorrow. Am J Surg. 2012;204:93-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Pollard JS, Fung AK, Ahmed I. Are natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery and single-incision surgery viable techniques for cholecystectomy? J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2012;22:1-14. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Perretta S, Vix M, Dallemagne B, Nassif J, Donatelli G, Marescaux J. Video. Repeated transvaginal notes: is it possible? Surg Endosc. 2012;26:565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Linke GR, Luz S, Janczak J, Zerz A, Schmied BM, Siercks I, Warschkow R, Beutner U, Tarantino I. Evaluation of sexual function in sexually active women 1 year after transvaginal NOTES: a prospective cohort study of 106 patients. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2013;398:139-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Linke GR, Tarantino I, Hoetzel R, Warschkow R, Lange J, Lachat R, Zerz A. Transvaginal rigid-hybrid NOTES cholecystectomy: evaluation in routine clinical practice. Endoscopy. 2010;42:571-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bingener J, Sloan JA, Ghosh K, McConico A, Mariani A. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of women’s perceptions of transvaginal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:998-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |