Published online Apr 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5072

Peer-review started: August 15, 2014

First decision: September 15, 2014

Revised: September 30, 2014

Accepted: October 21, 2014

Article in press: October 21, 2014

Published online: April 28, 2015

Processing time: 254 Days and 16.8 Hours

AIM: To assess the efficacy and safety of bevacizumab in the treatment of colorectal cancer.

METHODS: All randomized controlled trials of bevacizumab for the treatment of colorectal cancer from January 2003 to June 2013 were collected by searching the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases. The primary endpoint was overall survival (OS), and the secondary endpoints were progression-free survival, overall response rate and adverse events. Two reviewers extracted data independently. Statistical analyses were performed with Stata 12.0. The degree of bias was assessed using funnel plots for the effect size of OS at the primary endpoint.

RESULTS: Following the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, ten studies comprising 6977 cases were finally included, of which nine were considered to be of high quality (4-7 points) and one of low quality (1-3 points). Our meta-analysis revealed the efficacy of bevacizumab in patients with colorectal cancer in terms of OS (HR = 0.848, 95%CI: 0.747-0.963), progression-free survival (HR = 0.617, 95%CI: 0.530-0.719), and overall response rate (OR = 1.627, 95%CI: 1.199-2.207). Regarding safety, higher rates of grade ≥ 3 hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, thrombosis, and gastrointestinal perforation were observed in the bevacizumab treatment group (P < 0.05); however, the incidence of serious toxicity was very low. There was no publication bias in the 10 reports included in this meta-analysis.

CONCLUSION: The clinical application of bevacizumab in colorectal cancer is effective with good safety.

Core tip: Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy can provide a significant survival advantage in patients with colorectal cancer. Despite the increased risk of hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, thrombosis, gastrointestinal perforation and other adverse events, bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy deserves further promotion in future clinical work due to its low incidence of serious adverse events, excellent overall tolerance and good safety.

- Citation: Qu CY, Zheng Y, Zhou M, Zhang Y, Shen F, Cao J, Xu LM. Value of bevacizumab in treatment of colorectal cancer: A meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(16): 5072-5080

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i16/5072.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5072

Bevacizumab (BV) is a monoclonal antibody specific for recombinant humanized vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). It binds to VEGF and prevents its interaction with VEGF receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2), mediating inhibition of growth in a variety of tumors. In previous large-scale clinical studies, the survival benefit of bevacizumab therapy for colorectal cancer has proved controversial, and increased risk of hypertension, proteinuria, thrombosis, bleeding, and gastrointestinal perforation has been found[1-4]. Therefore, we conducted this meta-analysis of data collected on bevacizumab in the treatment of colorectal cancer to assess its efficacy and safety.

Inclusion criteria were: (1) histologically confirmed colorectal cancer by pathology; (2) 0-2 points according to Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score standard; (3) expected survival of more than three months; (4) older than 18 years of age; and (5) qualified hematology, liver and kidney function.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) non-randomized controlled trials; and (2) failure to comply with any of the above inclusion criteria.

Bevacizumab + chemotherapy vs placebo (or blank control) + chemotherapy.

Searches were performed for data recorded between January 2003 and June 2013 in the Cochrane Library, PubMed, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure and Wanfang databases. Additional references for the included literature were retrieved subsequently.

Keywords for retrieval were BV, colorectal cancer, randomized controlled trials and meta-analysis.

The quality of the included literature was appraised and graded according to a modified Jadad scale[5] as follows: 1-3 points, low quality; 4-7 points, high quality.

Hazard ratios (HRs) and odds ratios (ORs) were selected for the combined statistics of time-to-event data and combined statistics of the selected data, respectively. The heterogeneity analysis was performed before combining data (heterogeneity was quantitatively analyzed using I2): heterogeneity was considered mild when I2 < 25%; moderate when 25% ≤I2 < 50%; great when 50% ≤I2 < 75%; and high when 75% ≤I2 < 100%. The combined analysis using Stata12.0 software was performed for the data with low to moderate heterogeneity; descriptive analysis was performed for the data with high heterogeneity.

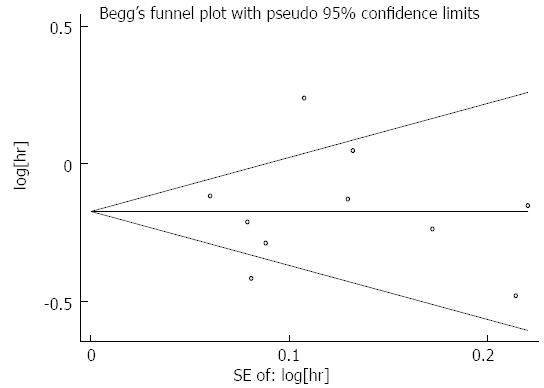

The degree of bias was assessed using funnel plots for the effect size of overall survival (OS) at the primary endpoint.

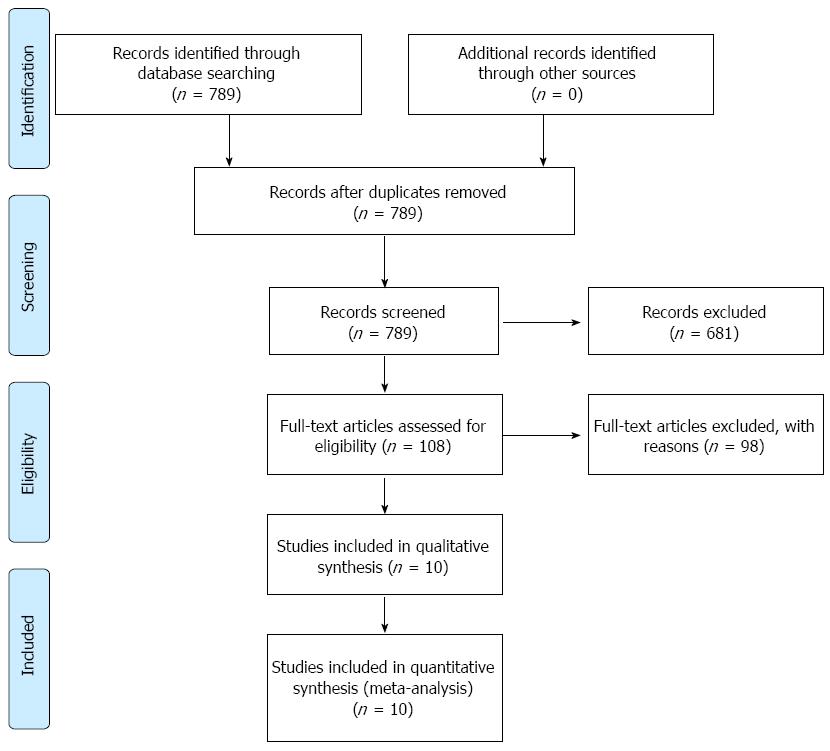

A total of 789 publications were retrieved. After reading the titles and abstracts, 681 reports of non-randomized controlled studies or those that were unrelated to our purpose were excluded. By reading the full texts of the remaining publications, eventually 10 randomized control studies[6-15] were included in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these, nine reports were considered to be of high quality (4-7 points)[6,7,9-15] and one of low quality (1-3 points)[8]. The 10 studies comprised 6977 cases in total, of which 3535 were from treatment groups and 3442 from control groups. The characteristics of the included data are shown in Table 1 and the flow chart in Figure 1.

| Ref. | No. of cases (control group/treatment group) | Bevacizumab treatment regimen | Modified Jadad score |

| Kabbinavar et al[9] | 104 (36/68) | 5 mg/kg or 10 mg/kg every 14 d | 4 |

| Kabbinavar et al[10] | 209 (105/104) | 5 mg/kg every 14 d | 5 |

| Tebbutt et al[11] | 312 (156/156) | 7.5 mg/kg every 21 d | 4 |

| Stathopoulos et al[6] | 224 (108/114) | 7.5 mg/kg every 21 d | 4 |

| Saltz et al[7] | 1400 (701/699) | 5 mg/kg every 14 dor 7.5 mg/kg every 21 d | 6 |

| Hurwitz et al[12] | 813 (411/402) | 5 mg/kg every 21 d | 4 |

| Giantonio et al[8] | 577 (291/286) | 10 mg/kg every 14 d | 3 |

| Guan et al[13] | 214 (72/142) | 5 mg/kg every 14 d | 4 |

| de Gramont et al[14] | 2306 (1151/1155) | 5 mg/kg every 14 d | 4 |

| Bennouna et al[15] | 820 (411/409) | 5 mg/kg every 14 d or 7.5 mg/kg every 14 d | 5 |

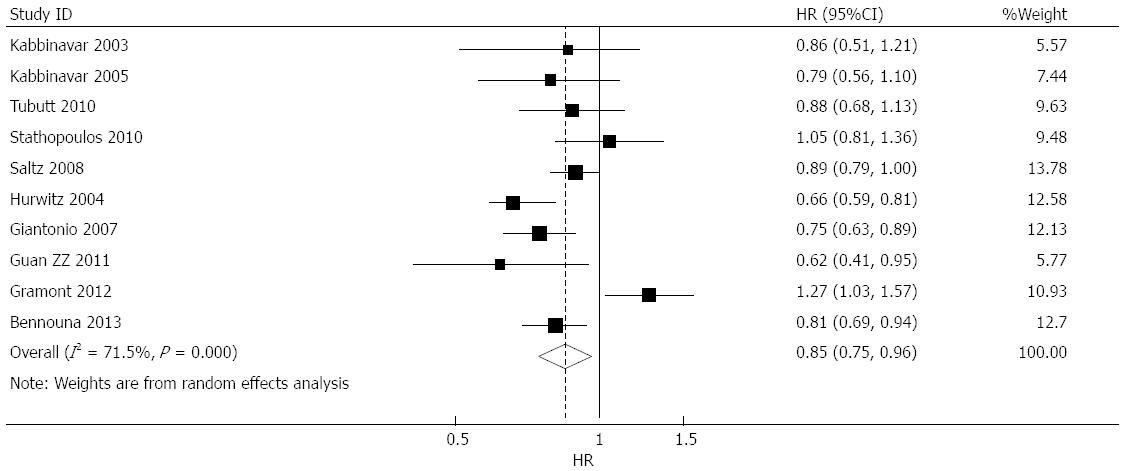

Effect of bevacizumab on OS: OS data were provided in 10 studies[6-15], of which four suggested that bevacizumab prolonged OS[8,12,13,15], five suggested that bevacizumab had no effect on OS[6,7,9-11], and one study suggested that bevacizumab treatment was associated with shortened OS[14]. The combined analysis of the 10 studies suggested moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 71.5%), and a combined HR of 0.848 (95%CI: 0.747-0.963, P = 0.011) was obtained using a random-effects model (Figure 2).

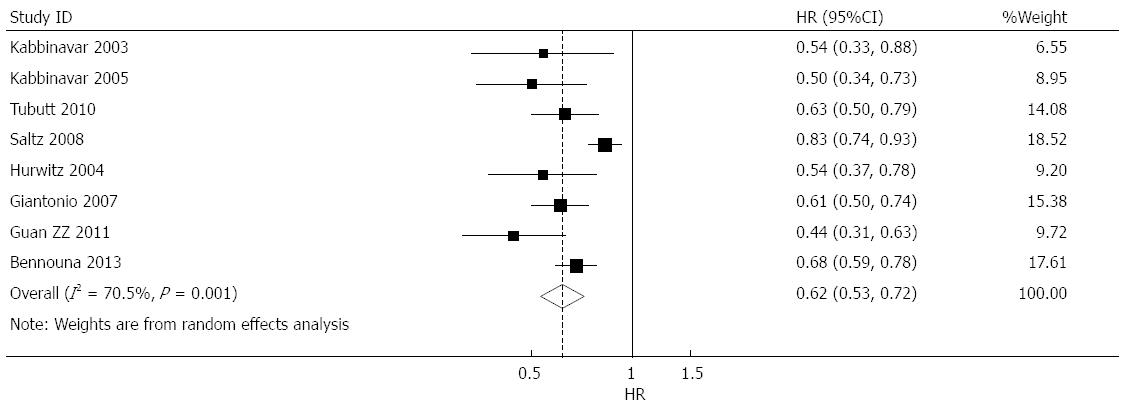

Effect of bevacizumab on progression-free survival: progression-free survival (PFS) data were provided in nine studies[7-15], of which eight suggested that bevacizumab prolonged PFS[7-13,15], and one suggested that bevacizumab treatment shortened PFS[14]. Combined analysis showed high heterogeneity of nine studies (I2 = 85.2%); thus only one study using adjuvant postoperative chemotherapy[14] resulting in potential heterogeneity was eliminated. The combined analysis of the remaining eight studies[7-13,15] revealed that heterogeneity fell to a moderate level (I2 = 70.5%), and a combined HR of 0.617 (95%CI: 0.530-0.719, P < 0.001) was obtained using a random-effects model (Figure 3).

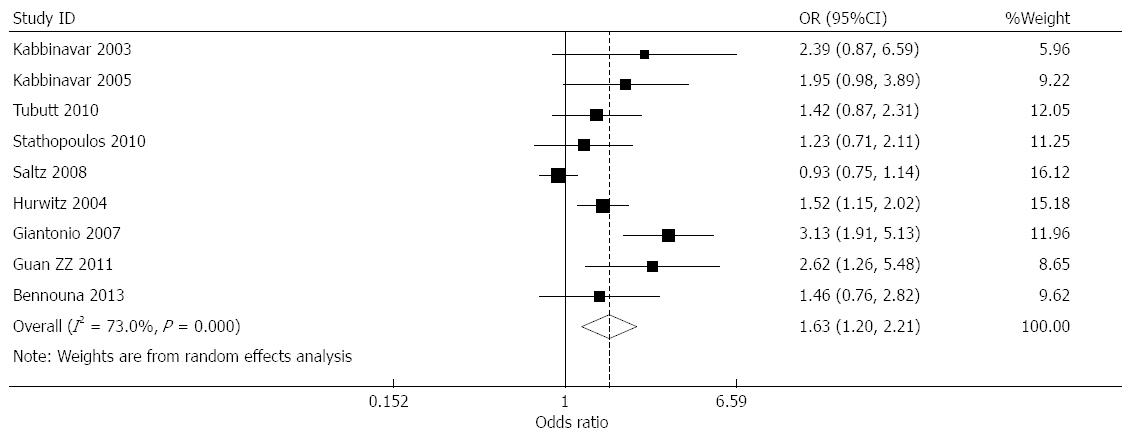

Effect of bevacizumab on overall response rate: overall response rate (ORR) data were provided by nine studies[6-13,15]. Among these, the response rates in the bevacizumab treatment and control groups were 33.5% and 28.3%, respectively. Combined analysis showed moderate heterogeneity for nine studies (I2 = 73%), and a combined OR of 1.627 (95%CI: 1.199-2.207, P = 0.002) was obtained using a random-effects model (Figure 4).

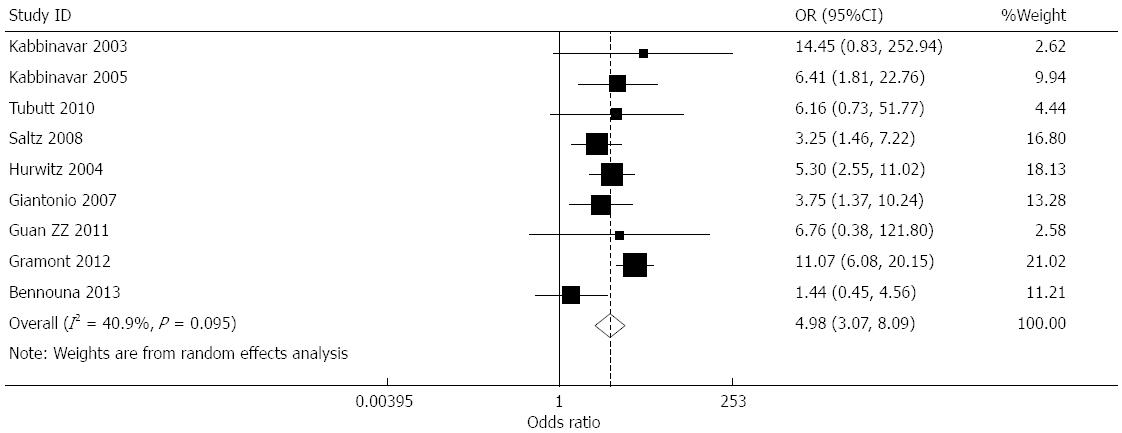

Effect of bevacizumab on hypertension (≥grade 3): Data for the incidence of hypertension were provided in nine studies[7-15]. The incidence of hypertension in the treatment and controls groups was 7.53%, and 1.32%, respectively. The heterogeneity of the combined results was moderate (I2 = 40.9%), and a combined OR of 4.982 (95%CI: 3.069-8.087, P < 0.001) was obtained using a random-effects model (Figure 5).

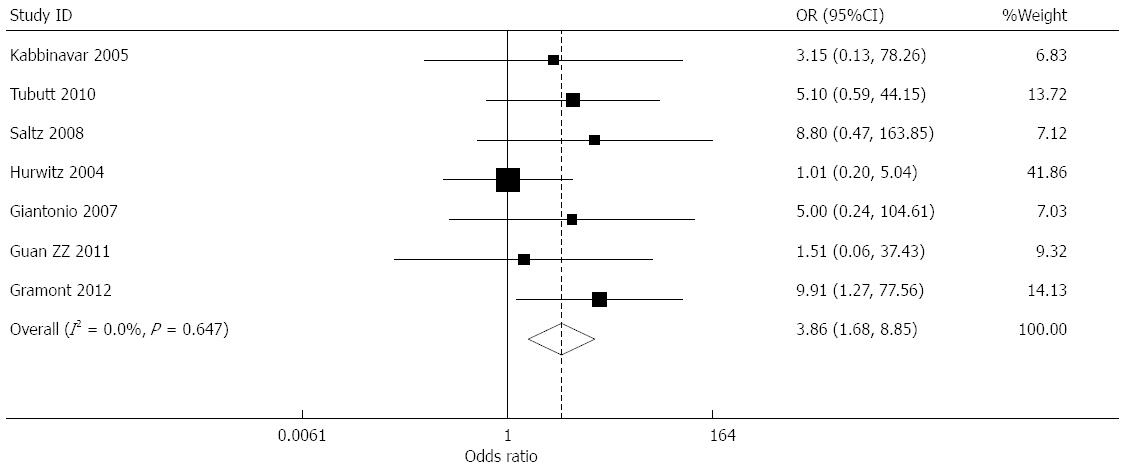

Effect of bevacizumab on proteinuria (≥grade 3): Data for the incidence of proteinuria were provided in seven studies[7,8,10-14]. The incidence of proteinuria in the treatment and control groups was 0.89% and 0.18%, respectively. The combined results presented little heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%), and a combined OR of 3.856 (95%CI: 1.681-8.848, P = 0.001) was obtained using a fixed effects model (Figure 6).

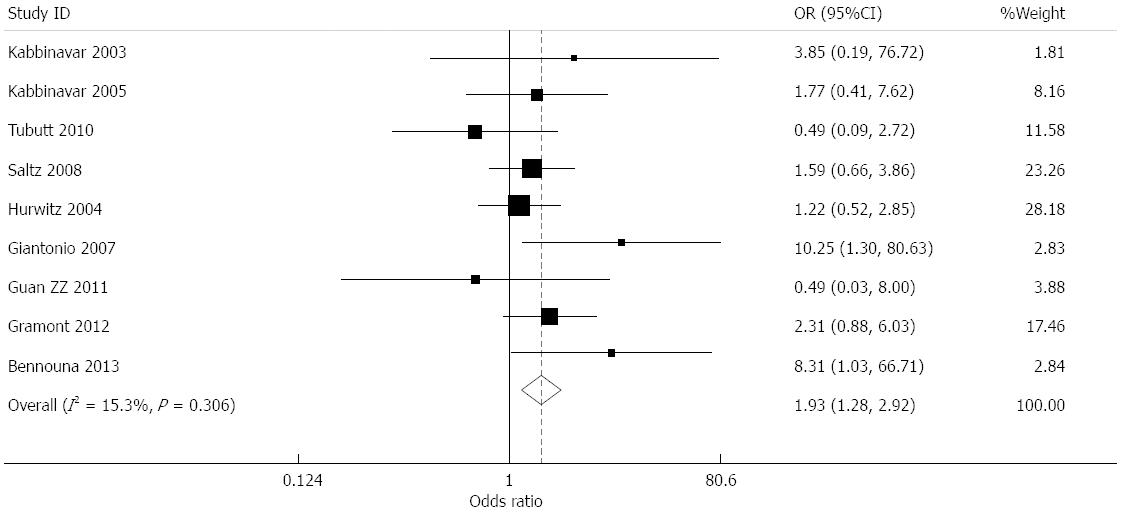

Effect of bevacizumab on bleeding (≥grade 3): Data for the incidence of bleeding were provided in nine studies[7-15]. The incidence of bleeding in the treatment and control groups was 1.77% and 1.04%, respectively. The combined results presented low heterogeneity (I2 = 15.3%), and a combined OR of 1.933 (95%CI: 1.279-2.922, P = 0.002) was obtained using a fixed effects model (Figure 7).

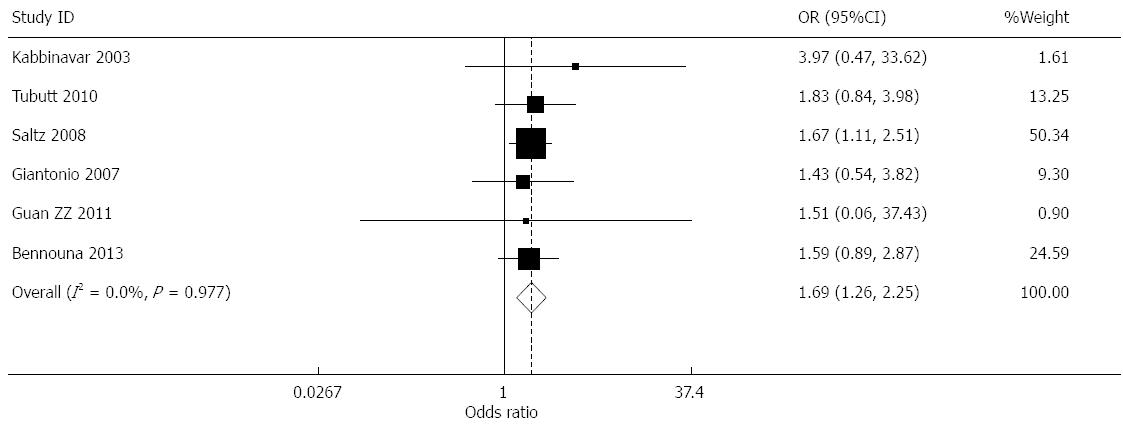

Effect of bevacizumab on thrombosis (≥grade 3): Data for the incidence of thrombosis were provided in seven studies[7-9,11,13-15]. The incidence of thrombosis in the treatment and control groups was 5.20% and 5.83%, respectively. The meta-analysis results indicated that the heterogeneity of the combined results was high (I2 = 88.3%). The sensitivity analysis was performed using the exclusion method. After eliminating the study reported by de Gramont et al[14], the heterogeneity fell to I2 = 0.0%. The high heterogeneity of these data was due to this study being conducted in postoperative patients; therefore, it was impossible to exclude the effects of the use of anticoagulants or hemostasis in the perioperative period on incidence of thrombus. By using a fixed effects model for the remaining six studies, the combined OR was 1.685 (95%CI: 1.262-2.249, P < 0.001) (Figure 8).

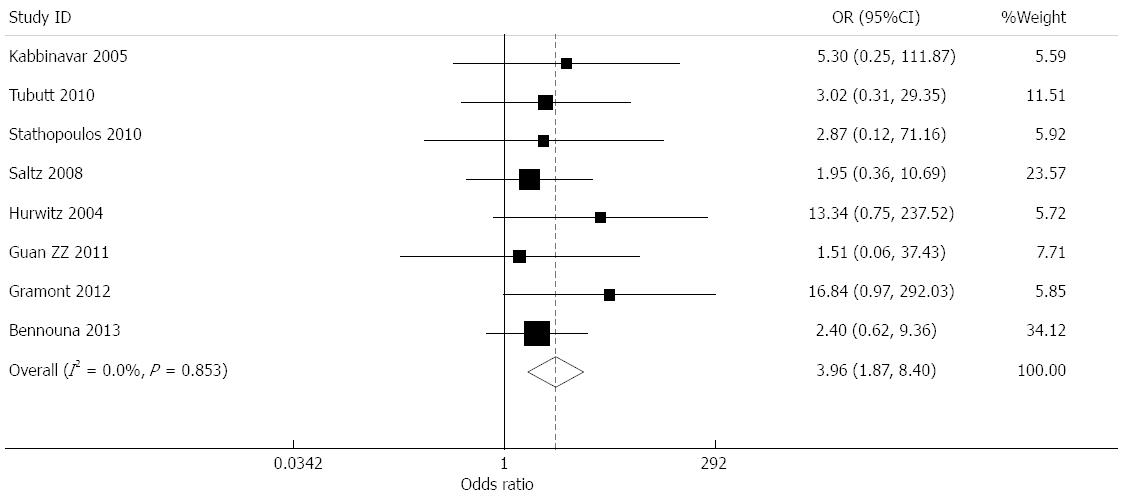

Effect of bevacizumab on gastrointestinal perforation: Data for the incidence of gastrointestinal perforation were provided in eight studies[6,7,10-15]. The incidence of gastrointestinal perforation in the treatment and control groups was 1.02% and 0.20%, respectively. The combined results presented little heterogeneity (I2 = 0.0%), and a combined OR of 3.958 (95%CI: 1.866-8.397, P < 0.001) was obtained using a fixed effects model (Figure 9).

Publication bias: Publication bias was assessed in terms of HR for the OS at the primary endpoint. As seen from the funnel chart shown in Figure 10, all studies were evenly distributed on both sides, thus presenting basic symmetry. This indicated that there was no publication bias in the 10 reports included in this meta-analysis (Begg’s test, P > 0.05).

Colorectal cancer is a common malignant neoplasm of the digestive system, with approximately 1.2 million new cases reported globally each year[16], ranking third in terms of global cancer incidence[17]. Approximately 25% of patients with colorectal cancer were found to have hepatic metastasis when initially diagnosed, and 25% of patients gradually developed liver or lung metastasis with disease progression[18]. Therefore, a safe and effective therapy for patients with colorectal cancer is urgently required. For patients in the early stages, surgery is still the most important method of treatment. However, for patients in advanced stage, most of whom are not suitable for surgery, the only remaining options are palliative therapies, such as chemotherapy, which is the most common choice, traditional Chinese medicine and biological target therapy. Common combined chemotherapy regimens include FOLFIRI[19], FOLFOX[20] and thymidylate synthase inhibitors (e.g., capecitabine)[21]. The efficiency of these regimens is only 30%-40%, even in frontline application; therefore, in order to improve the therapeutic effect for patients with colorectal cancer, molecularly targeted therapies have been developed[22], among which, combined chemotherapy has become an important choice[1].

Molecular targeted drugs exploit specific changes in tumor cells to achieve relative target specificity. This not only enhances the anti-cancer effect, but also reduces the damage to normal cells. Anti-angiogenic drugs have become a key to targeted therapy[23,24]. Bevacizumab is a monoclonal antibody specific for recombinant humanized vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which can block signal transduction via the VEGF receptor by binding to VEGF-A. This study assessed the efficacy and safety of bevacizumab in the treatment of colorectal cancer through meta-analysis of 10 randomized controlled trials including 6977 cases. Following grading using a modified Jadad scale, nine reports were deemed to be of high quality ones (4-7 points), and one of low quality (1-3 points). Funnel plots of the data revealed no significant publication bias.

OS data were provided for all 10 randomized controlled trials, and PFS and ORR data were provided for nine trials. The combined results suggested that, in the overall patient population, bevacizumab significantly increased OS (HR = 0.848, 95%CI: 0.747-0.963), prolonged PFS (HR = 0.617, 95%CI: 0.530-0.719), and improved the ORR (OR = 1.627, 95%CI: 1.199-2.207; P < 0.05 for all). These data indicated that bevacizumab treatment offers a significant survival advantage to patients with colorectal cancer.

Although studies have confirmed the survival benefit of bevacizumab, the toxic side-effects caused by bevacizumab should also be considered. According to previous reports, the most frequent adverse reactions to bevacizumab are hypertension and proteinuria, with gastrointestinal perforation being the most serious. Other side-effects include thrombosis and bleeding[1-4]. The results of our combined analysis of these adverse reaction data are consistent with previous studies. Although the incidence of gastrointestinal perforation caused by bevacizumab was increased by approximately 3-fold in the treatment group compared with that of the control group, the incidence in the eight studies included in this meta-analysis is relatively low (approximately 1%), suggesting that bevacizumab is safe and non-toxic. Compared to the control group, the treatment group has significantly higher incidence of hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, and thrombosis (P < 0.05). Although the results showed that incidence of hypertension (≥ grade 3) in the treatment group was approximately 5 times higher than that of the control group, published studies have shown that this side-effect can be controlled by oral antihypertensive agents[10].

Although incidence of other side-effects increased, most adverse reactions were grade 1/2, with few adverse reactions graded 3/4. Most clinical adverse reactions can be controlled, and no dose-limiting toxicity has been reported[25]. The incidence of adverse reactions can be limited by effective monitoring and prevention during the course of treatment.

The result of this meta-analysis suggests that bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy can provide a significant survival advantage by prolonging OS and PFS in patients with colorectal cancer, thus improving the ORRs. Despite the increased risk of hypertension, proteinuria, bleeding, thrombosis, gastrointestinal perforation and other adverse events, bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy deserves further promotion in future clinical work due to its low incidence of serious adverse events, excellent overall tolerance and good safety.

Colorectal cancer ranked third in terms of global cancer incidence. Approximately 25% of patients with colorectal cancer were found to have hepatic metastasis when initially diagnosed. Therefore, a safe and effective therapy for patients with colorectal cancer is urgently required.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) has been proved to be closely related to the growth of tumors. Bevacizumab (BV) is a monoclonal antibody specific for recombinant humanized VEGF. It binds to VEGF and prevents its interaction with VEGF receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2), mediating inhibition of growth in a variety of tumors.

There is not inherent innovation in this meta-analysis. However, it is informative to see the results of multiple studies compared next to each other.

Bevacizumab combined with chemotherapy provides a significant survival advantage in clinical use for patients with colorectal cancer.

VEGF mediates growth in a variety of tumors. BV is a monoclonal antibody specific for recombinant humanized VEGF. It binds to VEGF and prevents its interaction with VEGF receptors (VEGFR-1 and VEGFR-2), mediating inhibition of growth in a variety of tumors.

The authors present a meta-analysis of the safety and efficacy of bevacizumab treatment for colorectal cancer. This paper is well-written and the analysis is thorough. The statistical methods used are appropriate, and the conclusions are solid. The quality of English in the manuscript is also excellent, and the content concise.

P- Reviewer: Nishiyama M, Park JY, Ritchie S, Sugimura H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Scappaticci FA, Skillings JR, Holden SN, Gerber HP, Miller K, Kabbinavar F, Bergsland E, Ngai J, Holmgren E, Wang J. Arterial thromboembolic events in patients with metastatic carcinoma treated with chemotherapy and bevacizumab. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007;99:1232-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 706] [Cited by in RCA: 693] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nalluri SR, Chu D, Keresztes R, Zhu X, Wu S. Risk of venous thromboembolism with the angiogenesis inhibitor bevacizumab in cancer patients: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2277-2285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 574] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 33.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rafailidis PI, Kakisi OK, Vardakas K, Falagas ME. Infectious complications of monoclonal antibodies used in cancer therapy: a systematic review of the evidence from randomized controlled trials. Cancer. 2007;109:2182-2189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saif MW, Elfiky A, Salem RR. Gastrointestinal perforation due to bevacizumab in colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1860-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Stathopoulos GP, Batziou C, Trafalis D, Koutantos J, Batzios S, Stathopoulos J, Legakis J, Armakolas A. Treatment of colorectal cancer with and without bevacizumab: a phase III study. Oncology. 2010;78:376-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Saltz LB, Clarke S, Díaz-Rubio E, Scheithauer W, Figer A, Wong R, Koski S, Lichinitser M, Yang TS, Rivera F. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2013-2019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2302] [Cited by in RCA: 2269] [Article Influence: 133.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Giantonio BJ, Catalano PJ, Meropol NJ, O’Dwyer PJ, Mitchell EP, Alberts SR, Schwartz MA, Benson AB. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin (FOLFOX4) for previously treated metastatic colorectal cancer: results from the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Study E3200. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1539-1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1806] [Cited by in RCA: 1726] [Article Influence: 95.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Kabbinavar F, Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Meropol NJ, Novotny WF, Lieberman G, Griffing S, Bergsland E. Phase II, randomized trial comparing bevacizumab plus fluorouracil (FU)/leucovorin (LV) with FU/LV alone in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:60-65. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Kabbinavar FF, Schulz J, McCleod M, Patel T, Hamm JT, Hecht JR, Mass R, Perrou B, Nelson B, Novotny WF. Addition of bevacizumab to bolus fluorouracil and leucovorin in first-line metastatic colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3697-3705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 674] [Cited by in RCA: 657] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tebbutt NC, Wilson K, Gebski VJ, Cummins MM, Zannino D, van Hazel GA, Robinson B, Broad A, Ganju V, Ackland SP. Capecitabine, bevacizumab, and mitomycin in first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the Australasian Gastrointestinal Trials Group Randomized Phase III MAX Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3191-3198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 297] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hurwitz HI, Fehrenbacher L, Hainsworth JD, Heim W, Berlin J, Holmgren E, Hambleton J, Novotny WF, Kabbinavar F. Bevacizumab in combination with fluorouracil and leucovorin: an active regimen for first-line metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3502-3508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 494] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 24.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Guan ZZ, Xu JM, Luo RC, Feng FY, Wang LW, Shen L, Yu SY, Ba Y, Liang J, Wang D. Efficacy and safety of bevacizumab plus chemotherapy in Chinese patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III ARTIST trial. Chin J Cancer. 2011;30:682-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | de Gramont A, Van Cutsem E, Schmoll HJ, Tabernero J, Clarke S, Moore MJ, Cunningham D, Cartwright TH, Hecht JR, Rivera F. Bevacizumab plus oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as adjuvant treatment for colon cancer (AVANT): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:1225-1233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bennouna J, Sastre J, Arnold D, Österlund P, Greil R, Van Cutsem E, von Moos R, Viéitez JM, Bouché O, Borg C. Continuation of bevacizumab after first progression in metastatic colorectal cancer (ML18147): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 760] [Cited by in RCA: 897] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7953] [Cited by in RCA: 8101] [Article Influence: 506.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Ochenduszko SL, Krzemieniecki K. Targeted therapy in advanced colorectal cancer: more data, more questions. Anticancer Drugs. 2010;21:737-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Takayama T, Miyanishi K, Hayashi T, Sato Y, Niitsu Y. Colorectal cancer: genetics of development and metastasis. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jonker D, Earle C, Kocha W. Use of irinotecan combined with 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin as first-line therapy for metastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol. 2001;8:60-68. |

| 20. | Hochster HS, Hart LL, Ramanathan RK, Childs BH, Hainsworth JD, Cohn AL, Wong L, Fehrenbacher L, Abubakr Y, Saif MW. Safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin and fluoropyrimidine regimens with or without bevacizumab as first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer: results of the TREE Study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3523-3529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kocha W, Maroun J, Jonker D. Oral capecitabine (Xeloda) in the first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. Curr Oncol. 2004;11:81-92. |

| 22. | Venook A. Critical evaluation of current treatments in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2005;10:250-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ide A, Baker N, Warren S. Vascularization of the Brown Pearce rabbit epithelioma transplant as seen in the transparent ear chamber. Am J Roentgenol. 1939;42:891-899. |

| 24. | Algire G, Chalkley H, Legallais F. Vascular reactions of mice to wounds and to normal and neoplastic transplants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1945;6:73-85. |

| 25. | Saif MW, Mehra R. Incidence and management of bevacizumab-related toxicities in colorectal cancer. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2006;5:553-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |