Published online Apr 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5032

Peer-review started: October 15, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: November 27, 2014

Accepted: January 16, 2015

Article in press: January 16, 2015

Published online: April 28, 2015

Processing time: 194 Days and 8.9 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy as first-line eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

METHODS: From December 2013 to August 2014, 161 patients with confirmed H. pylori infection randomly received 14 d of moxifloxacin-based sequential group (MOX-ST group, n = 80) or clarithromycin-based sequential group (CLA-ST group, n = 81) therapy. H. pylori infection was defined on the basis of at least one of the following three tests: a positive 13C-urea breath test; histologic evidence of H. pylori by modified Giemsa staining; or a positive rapid urease test (CLOtest; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) by gastric mucosal biopsy. Successful eradication therapy for H. pylori infection was defined as a negative 13C-urea breath test four weeks after the end of eradication treatment. Compliance was defined as good when drug intake was at least 85%. H. pylori eradication rates, patient compliance with drug treatment, adverse event rates, and factors influencing the efficacy of eradication therapy were evaluated.

RESULTS: The eradication rates by intention-to-treat analysis were 91.3% (73/80; 95%CI: 86.2%-95.4%) in the MOX-ST group and 71.6% (58/81; 95%CI: 65.8%-77.4%) in the CLA-ST group (P = 0.014). The eradication rates by per-protocol analysis were 93.6% (73/78; 95%CI: 89.1%-98.1%) in the MOX-ST group and 75.3% (58/77; 95%CI: 69.4%-81.8%) in the CLA-ST group (P = 0.022). Compliance was 100% in both groups. The adverse event rates were 12.8% (10/78) and 24.6% (19/77) in the MOX-ST and CLA-ST group, respectively (P = 0.038). Most of the adverse events were mild-to-moderate in intensity; there was none serious enough to cause discontinuation of treatment in either group. In multivariate analysis, advanced age (≥ 60 years) was a significant independent factor related to the eradication failure in the CLA-ST group (adjusted OR = 2.13, 95%CI: 1.97-2.29, P = 0.004), whereas there was no significance in the MOX-ST group.

CONCLUSION: The 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is effective. Moreover, it shows excellent patient compliance and safety compared to the 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy.

Core tip: This is the first study to evaluate the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy compared to that of 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy as a first-line eradication treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection. Our study showed that the moxifloxacin-based therapy is effective and shows excellent patient compliance and safety compared with the clarithromycin-based sequential therapy. The high eradication rate, excellent compliance, and safety of the moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy suggest its suitability as an alternative to standard triple therapy.

-

Citation: Hwang JJ, Lee DH, Lee AR, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N. Efficacy of moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy for first-line eradication of

Helicobacter pylori infection in gastrointestinal disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(16): 5032-5038 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i16/5032.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.5032

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is the single most important factor causing chronic atrophic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, gastric cancer, and gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma[1]. The eradication of H. pylori infection effectively reduces the incidence of peptic ulcer and gastric cancer and prevents their recurrence[2]. The most important first-line treatment for eradication of H. pylori is currently the standard triple therapy comprising a proton pump inhibitor (PPI), clarithromycin, and either amoxicillin or metronidazole[3,4]. Although many studies have indicated that this therapy is highly effective, the reported eradication rates vary between 70% and 95%[5,6] and have shown a tendency to decrease due to increasing antibiotic resistance[7,8]. Therefore, more effective alternative regimens are needed.

Many alternative, first-line treatment regimens have been studied. Sequential therapy is one alternative regimen, which consists of a PPI and amoxicillin for the first seven days, followed by a PPI plus metronidazole and clarithromycin for another seven days[9]. This regimen is currently recommended as an alternative first-line treatment for H. pylori infection in European guidelines[3]. In Korea, a region with relatively high antibiotic resistance, the efficacy of sequential therapy has been reported in several randomized controlled trials, including our previous prospective study[10-12]. These studies initially indicated sequential therapy to be effective, but recent studies have shown less satisfactory results. The main causes of sequential therapy failure are patient non-compliance and antibiotic resistance[13]. Non-compliance is due mainly to patients’ complicated schedules[14]. Another key element of treatment failure is bacterial resistance to clarithromycin. Resistance to clarithromycin is relatively high in Korea[15,16] and plays an role in diminishing the effect of sequential therapy[13].

Recently, changing the antibiotic agents that are included in the eradication regimen to improve H. pylori eradication therapy efficacy has been studied. The reason for changing antibiotic agents is to overcome resistance to clarithromycin. Among several candidates for new antibiotic agents, moxifloxacin has received attention. Compared with other fluoroquinolones, moxifloxacin has a low incidence of adverse events and small interactions with other drugs. Therefore, we hypothesized that 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy might increase H. pylori eradication as compared to clarithromycin-based sequential therapy in an area with high clarithromycin resistance. A head-to-head comparison between moxifloxacin and clarithromycin regimens has not been addressed in the literature yet.

The aim of the present study was to compare the H. pylori eradication rates, patient compliance, and adverse events between first-line moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy and clarithromycin-based sequential therapy.

This study was conducted at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between December 2013 and August 2014. A total of 161 patients with H. pylori infection were enrolled in this prospective, open-labeled, randomized pilot study. H. pylori infection was defined on the basis of at least one of the following three tests: (1) a positive 13C-urea breath test (13C-UBT); (2) histologic evidence of H. pylori by modified Giemsa staining in the lesser and greater curvature of the body and antrum of the stomach; or (3) a positive rapid urease test (CLOtest; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) by gastric mucosal biopsy from the lesser curvature of the body and antrum of the stomach. Patients were excluded if they had received PPIs, H2 receptor antagonists, or antibiotics in the previous four weeks, or if they had used non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs or steroids in the two weeks prior to the 13C-UBT. The other exclusion criteria were age below 18 years, previous gastric surgery, or endoscopic mucosal dissection for gastric cancer, advanced gastric cancer, severe current disease (hepatic, renal, respiratory, or cardiovascular), pregnancy, and any condition thought to be associated with poor compliance (e.g., alcoholism or drug addiction).

This prospective, open-labeled, single-center, randomized pilot study compared 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy with 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy as a first-line eradication treatment of H. pylori infection. All enrolled participants filled in a questionnaire on demographic information, history of comorbidities, body mass index (BMI), smoking habit, and alcohol consumption. Each participant underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy to confirm clinical diagnosis (such as gastritis or peptic ulcer disease) and to conduct a biopsy for H. pylori infection, colonization, atrophic changes, and intestinal metaplasia.

The 161 participants were randomly assigned to one of the two treatment groups using a computer-generated numeric sequence. The 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy group (MOX-ST group, n = 80) received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for the first week, followed by 20 mg rabeprazole twice daily, 500 mg metronidazole twice daily, and moxifloxacin 400 mg once daily for the remaining week. Participants in the 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy group (CLA-ST group, n = 81) received 20 mg rabeprazole and 1 g amoxicillin twice daily for the first week, followed by 20 mg rabeprazole, 500 mg metronidazole, and clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily for the remaining one week.

Patient compliance was evaluated by remnant pill counting and direct questions from a physician 1 wk after completion of the treatment. Compliance was defined as good when less than 15% of the pills were unconsumed at remnant pill counting. At the same time, all of the patients were asked about adverse events. Successful eradication therapy for H. pylori infection was defined as a negative 13C-UBT test four weeks after the cessation of eradication treatment. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB number: B-1409/268-103).

Before the 13C-UBT, the patients were instructed to stop taking medications (i.e., antibiotics for 4 wk, or PPIs for 2 wk) that could affect the result, and fasted for a minimum of 4 h. After patients cleaned their oral cavities by gargling, a pre-dose breath sample was obtained. Then, 100 mg of 13C-urea powder (UBiTkitTM; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was dissolved in 100 mL of water and was administered orally, and an additional breath sample was obtained. Breath samples were taken with special breath collection bags while patients were in the sitting position, both before drug administration (baseline) and 20 min after the powder medication. The samples were analyzed using an isotope-selective, non-dispersive infrared spectrometer (UBiT-IR 300®; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan).

The primary and secondary outcomes of the present study were H. pylori eradication rates and treatment-related adverse events, respectively. The eradication rates were determined by intention-to-treat (ITT) and per-protocol (PP) analyses. ITT analysis compared the treatment groups, including all patients as originally allocated; the PP analysis compared the treatment groups, including only those patients who had completed the treatment as originally allocated. Mean standard deviations were calculated for quantitative variables. Student’s t test was used to evaluate the continuous variables, and χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test were utilized to assess the non-continuous variables. Additionally, univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to assess the effects of factors on the eradication rate. All statistical analyses were performed using the Predictive Analytics Software 20.0 version for Windows (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). A P value of less than 0.05 was defined as clinically significant.

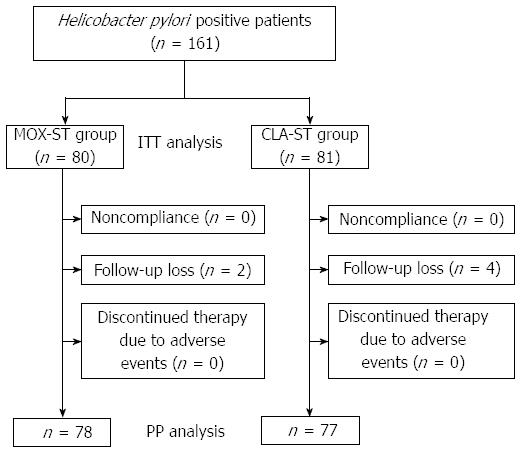

A schematic diagram of the study is provided in Figure 1. A total of 161 patients with H. pylori infection were randomly allocated to the MOX-ST group or the CLA-ST group by 1:1. Of the 161 patients, 155 (96.2%) completed their allocated regimens. The remaining six patients (3.8%) were excluded from study analysis. Therefore, 78 MOX-ST patients and 77 CLA-ST patients were included in the PP analysis. The enrolled patients’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics did not statistically differ between the two groups (Table 1).

| MOX-ST | CLA-ST | P value | |

| Included in ITT analysis | 80 | 81 | NS |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 59.3 ± 13.1 | 59.4 ± 13.1 | 0.235 |

| Gender (male) | 34 (42.5) | 33 (40.7) | 0.773 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 22.9 ± 2.2 | 22.7 ± 2.9 | 0.352 |

| Current smoker | 11 (13.7) | 10 (12.3) | 0.385 |

| Alcohol drinking | 13 (16.2) | 9 (11.1) | 0.351 |

| Diabetes | 5 (6.2) | 8 (9.8) | 0.125 |

| Hypertension | 19 (23.7) | 23 (28.3) | 0.407 |

| Previous history of peptic ulcer | 12 (15.0) | 9 (11.1) | 0.348 |

| Endoscopic diagnosis | 0.624 | ||

| Gastritis | 70 (87.6) | 70 (86.6) | |

| Gastric ulcer | 4 (5.0) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Gastric and duodenal ulcer | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Adenoma | 4 (5.0) | 4 (4.9) | |

| Dysplasia | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) | |

| Positive CLOtest | 59 (73.7) | 62 (76.5) | 0.955 |

| H. pylori colonization | 0.588 | ||

| Negative | 3 (3.7) | 5 (6.1) | |

| Mild | 34 (42.5) | 36 (44.4) | |

| Moderate | 32 (40.0) | 24 (29.6) | |

| Marked | 11 (13.8) | 16 (19.9) | |

| Atrophic change | 8 (10.0) | 2 (2.4) | 0.087 |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 10 (12.5) | 13 (16.0) | 0.761 |

| Drop out | 2 (2.5) | 4 (4.9) | 0.113 |

| Noncompliance | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Follow-up loss | 2 (2.5) | 4 (4.9) | |

| Discontinued therapy due to adverse events | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Table 2 shows the rates of eradication of H. pylori infection according to the ITT and PP analyses. The overall ITT eradication rate was 81.3% (131/161). The final ITT eradication rates were 91.3% [73/80; 95%CI: 86.2-95.4%] in the MOX-ST group and 71.6% (58/81; 95%CI: 65.8-77.4%) in the CLA-ST group (P = 0.014; Table 2). The overall PP eradication rate was 84.5% (131/155), and the final PP eradication rates were 93.6% (73/78; 95%CI: 89.1%-98.1%) in the MOX-ST group and 75.3% (58/77; 95%CI: 69.4%-81.8%) in the CLA-ST group (P = 0.022; Table 2). The H. pylori-eradication rates in the MOX-ST group were significantly higher than those in the CLA-ST group, according to both the ITT (P = 0.014) and the PP analysis (P = 0.022).

| MOX-ST | CLA-ST | P value | |

| ITT analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 91.3% (73/80) | 71.6% (58/81) | 0.014 |

| 95%CI | 86.2%-95.4% | 65.8%-77.4% | |

| PP analysis | |||

| Eradication rate | 93.6% (73/78) | 75.3% (58/77) | 0.022 |

| 95%CI | 89.1%-98.1% | 69.4%-81.8% |

To evaluate the clinical factors influencing the efficacy of H. pylori eradication, univariate analyses were performed (as listed in Table 3). In the CLA-ST group, the eradication rates of participants over 60 years of age was significantly lower than those of participants under 60 years of age (P = 0.002; Table 3). Other factors in the CLA-ST group did not affect the eradication response. No factors in the MOX-ST group affected the eradication response. The multivariate analysis revealed that age greater than 60 years [adjusted OR = 2.13, 95%CI: 1.97-2.29, P = 0.004] was an independent factor predictive of eradication failure in the CLA-ST group.

| MOX-ST | CLA-ST | |||

| Eradication rate | P value | Eradication rate | P value | |

| Age (yr) | 0.436 | 0.002 | ||

| < 60 | 97.2% (35/36) | 81.1% (30/37) | ||

| ≥ 60 | 90.4% (38/42) | 70.0% (28/40) | ||

| Gender | 0.383 | 0.622 | ||

| Male | 91.1% (31/34) | 71.8% (23/32) | ||

| Female | 95.4% (42/44) | 77.7% (35/45) | ||

| Body mass index | 0.651 | 0.743 | ||

| < 25 | 95.2% (20/21) | 86.9% (20/23) | ||

| ≥ 25 | 92.9% (53/57) | 70.3% (38/54) | ||

| Smoking | 0.585 | 0.377 | ||

| (-) | 97.0% (65/67) | 77.6% (52/67) | ||

| (+) | 72.7% (8/11) | 60.0% (6/10) | ||

| Alcohol | 0.417 | 0.082 | ||

| (-) | 96.9% (63/65) | 77.9% (53/68) | ||

| (+) | 76.9% (10/13) | 55.5% (5/9) | ||

| Diabetes | 0.706 | 0.107 | ||

| (-) | 94.5% (70/74) | 76.8% (53/69) | ||

| (+) | 75.0% (3/4) | 62.5% (5/8) | ||

| Hypertension | 0.322 | 0.096 | ||

| (-) | 91.6% (55/60) | 79.6% (43/54) | ||

| (+) | 100.0% (18/18) | 65.2% (15/23) | ||

| History of ulcer | 0.454 | 0.828 | ||

| (-) | 92.5% (62/67) | 75.0% (51/68) | ||

| (+) | 100.0% (11/11) | 77.7% (7/9) | ||

| Presence of ulcer | 0.352 | 0.076 | ||

| (-) | 92.6% (63/68) | 78.7% (52/66) | ||

| (+) | 100.0% (10/10) | 54.5% (6/11) | ||

| Positive CLOtest | 0.259 | 0.374 | ||

| (-) | 76.1% (16/21) | 63.1% (12/19) | ||

| (+) | 100.0% (57/57) | 79.3% (46/58) | ||

| Atrophic change | 0.111 | 0.071 | ||

| (-) | 95.7% (67/70) | 76.0% (57/75) | ||

| (+) | 75.0% (6/8) | 50.0% (1/2) | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.270 | 0.322 | ||

| (-) | 95.5% (65/68) | 76.5% (49/64) | ||

| (+) | 80.0% (8/10) | 69.2% (9/13) | ||

| Bacterial density | 0.296 | 0.507 | ||

| None | 66.7% (2/3) | 60.0% (3/5) | ||

| Mild | 90.6% (29/32) | 67.6% (23/34) | ||

| Moderate | 100.0% (32/32) | 78.2% (18/23) | ||

| Marked | 90.9% (10/11) | 93.3% (14/15) | ||

| Compliance | NS | NS | ||

| Poor | 0.0% (0/0) | 0.0% (0/0) | ||

| Good | 93.6% (73/78) | 75.3% (58/77) | ||

| Adverse events | 0.493 | 0.494 | ||

| (-) | 92.6% (63/68) | 77.6% (45/58) | ||

| (+) | 100.0% (10/10) | 68.4% (13/19) | ||

Table 4 lists the adverse events that occurred in the two groups. Adverse events occurred for 10 of 78 patients (12.8%) in the MOX-ST group and for 19 of 77 patients (24.6%) in the CLA-ST group. The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.038). The most common adverse events were bloating/dyspepsia (4/78, 5.1%) and taste distortion (3/78, 3.8%) in the MOX-ST group and epigastric discomfort (5/77, 6.4%) and taste distortion (5/77, 6.4%) in the CLA-ST group. These differences were not statistically significant (P > 0.05). Most of the adverse events were mild-to-moderate in intensity; there was none serious enough to cause discontinuation of treatment in either group. The treatment compliance (as defined as taking at least 85% of scheduled medication doses) was 100% in both groups (Table 4).

| Adverse events | MOX-ST(n = 78) | CLA-ST(n = 77) | P value |

| Bloating/dyspepsia | 4 (5.1) | 4 (5.3) | 0.383 |

| Taste distortion | 3 (3.8) | 5 (6.4) | 0.316 |

| Epigastric discomfort | 2 (2.6) | 5 (6.4) | 0.296 |

| Nausea | 1 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 0.505 |

| Abdominal pain | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.3) | 0.309 |

| Diarrhea | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.9) | 0.075 |

| Constipation | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | NS |

| Total | 10 (12.8) | 19 (24.6) | 0.038 |

| Compliance, n (%) | 78 (100.0) | 77 (100.0) | NS |

To our knowledge, this is the first study that evaluated the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy compared with 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy as a first-line eradication treatment of H. pylori infection. In this study, eradication rates in the MOX-ST group (ITT: 91.3%; PP: 93.6%) were higher than those in the CLA-ST group (71.6%/75.3%), with statistically significant differences (P < 0.05). These results represented statistically significant differences: namely, markedly higher eradication rates for the MOX-ST group (P < 0.05). Moreover, the total adverse-event rate for the MOX-ST group was 12.8% (10/78), which was significantly lower than that for the CLA-ST group (24.6%, 19/77), with statistically differences (P = 0.038). The drug compliance was 100% in both groups. Thus, our study showed the 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is effective and shows excellent compliance and safety compared with the 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy.

In the clarithromycin-based sequential therapy, the key theoretical basis is the effect of amoxicillin on the bacterial cell wall. Amoxicillin administered in the first half of the regimen damages cell wall of H. pylori; this is thought to overcome antibiotic resistance and increase eradication rate by two mechanisms. First, damage to the cell wall damage may ease the penetration of subsequent antibiotics into the H. pylori strain. Second, the damaged cell wall cannot develop efflux channels for clarithromycin[17,18]. Several large, multicenter studies have reported high eradication rates with clarithromycin-based sequential therapy[11,19,20]. An earlier Korean study on clarithromycin-based sequential therapy performed in 2008 and 2009 reported a high eradication rate (85.9% by ITT analysis and 92.6% by PP analysis)[21]. However, subsequent studies performed in our institution suggest efficacy of clarithromycin-based sequential therapy is decreasing in Korea. The eradication rate of clarithromycin-based sequential therapy was 79.3% by ITT analysis and 81.9% by PP analysis in 2009 and 2010[10], 75.6% (ITT) and 76.8% (PP) in 2011 and 2012[22], and 71.6% (ITT) and 75.3% (PP) in 2013 and 2014 in these study. These findings imply that resistance to antibiotics in H. pylori treatment is increasing, and that clarithromycin-based sequential therapy might already be suboptimal in areas with high prevalence of clarithromycin resistance.

A recent meta-analysis evaluating H. pylori strains in Western populations found fluoroquinolone-resistance prevalence in less than 5.0%[15]. Fluoroquinolone resistance in Japan is 15%[23]. In Gyeonggi Province, Korea, the rates of resistance were 5.0% for levofloxacin and moxifloxacin, 5.0% for amoxicillin, 16.7% for clarithromycin, 34.3% for metronidazole, and 8.0% for tetracycline[8]. These results might be related to different patterns of regional and institutional fluoroquinolone use[24]. This explains why a moxifloxacin-based triple regimen achieved successful eradication in 84%-87% of cases (by PP analysis), as compared with the markedly lower rates recorded for levofloxacin-based triple regimens elsewhere in Asia[25-28]. These results suggest that appropriate H. pylori-eradication therapies should be continually adjusted according to local bacterial resistance patterns. Therefore, we could explain that the reason moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is more effective than clarithromycin-based sequential therapy in Korea is the low resistance to moxifloxacin compared with clarithromycin.

Our study showed that advanced age (≥ 60 years) was a significant independent factor related to the eradication failure in the CLA-ST group, whereas there was no significance in the MOX-ST group in multivariate analysis. Other studies have also reported that advanced age was associated with treatment failure in H. pylori eradication therapy[29,30]. However, the mechanisms by which advanced age interfere with eradication remain unclear. Immunity degradation, which is one of the physiological changes of the human body by aging, may be associated with poor treatment response[31]. Further studies are needed to investigate the mechanisms underlying the association between advanced age and poor response to eradication treatment.

The most common adverse events of moxifloxacin are gastrointestinal disturbances, such as diarrhea and nausea. In the present study, the most common adverse events were taste distortion, epigastric discomfort, and abdominal bloating. The total adverse-event rate for the 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential treatment was 12.8% (10/78), which was significantly lower than that for the 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential treatment (24.6%, 19/77). In both groups, the adverse events were mild to moderate; none was serious enough to require discontinuation or interfered with regular life.

This study has several limitations. First, this study was a single-center pilot study with a relatively small sample size. Larger prospective studies will be needed to confirm our results in regions where different patterns of resistant are present. However, we think our exploratory study would be a good reference for clinicians and researchers to help design new studies on this subject. Second, we could not investigate the antibiotic resistance in each patient. However, this was a pilot study comparing alternative first-line regimens in a Korean population. Moreover, selection bias is ruled out by randomized allocation of the participants, so that the prevalence of primary antibiotic resistance is expected to be equally distributed among the therapeutic groups.

In conclusion, 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy is a more effective first-line eradication treatment than 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy for H. pylori infection. The high eradication rate, excellent patient compliance, and safety of the moxifloxacin-based therapy suggest its suitability as an alternative to standard triple therapy. Further large prospective studies are required to determine the broad application of this regimen in comparison with currently approved first-line therapies.

A recent meta-analysis reported that the efficacy of sequential therapy for Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is modest in Asia, exemplifying the need to find a better regimen.

The potential role of moxifloxacin as an antibiotic agent useful for eradication treatment in H. pylori infection has been suggested by a few animal and human studies.

This is the first randomized controlled study to evaluate the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy (as compared with 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy) as a first-line eradication treatment of H. pylori infection. The high eradication rate, excellent compliance, and safety of the 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy suggest its suitability as an alternative to the standard triple therapy.

This pilot study’s design and findings could be used to determine sample size for a larger, prospective study aiming to test the efficacy of moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy for H. pylori eradication.

H. pylori is found in the stomach and is linked to the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers, and stomach cancer. To prevent recurrence in patients with these diseases, it is necessary to eradicate H. pylori infection.

This study presents a topic of interest in clinical practice, not often considered in literature. Methods and study population are adequate, and conclusions are reasonable and of possible practical use. This article presents an important issue. This is the first study to compare the efficacy of 14-d moxifloxacin-based sequential therapy with that of 14-d clarithromycin-based sequential therapy.

P- Reviewer: Annibale B, Kupcinskas L, Paulssen EJ S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer: a model. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1983-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS, Turney EA. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1244-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O’Morain CA, Atherton J, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gensini GF, Gisbert JP, Graham DY, Rokkas T. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection--the Maastricht IV/ Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2012;61:646-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1719] [Cited by in RCA: 1588] [Article Influence: 122.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 4. | Chey WD, Wong BC. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 819] [Cited by in RCA: 830] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | Lam SK, Talley NJ. Report of the 1997 Asia Pacific Consensus Conference on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 288] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Laheij RJ, Rossum LG, Jansen JB, Straatman H, Verbeek AL. Evaluation of treatment regimens to cure Helicobacter pylori infection--a meta-analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:857-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim JM, Kim JS, Jung HC, Kim N, Kim YJ, Song IS. Distribution of antibiotic MICs for Helicobacter pylori strains over a 16-year period in patients from Seoul, South Korea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4843-4847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kim N, Kim JM, Kim CH, Park YS, Lee DH, Kim JS, Jung HC, Song IS. Institutional difference of antibiotic resistance of Helicobacter pylori strains in Korea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:683-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zullo A, Rinaldi V, Winn S, Meddi P, Lionetti R, Hassan C, Ripani C, Tomaselli G, Attili AF. A new highly effective short-term therapy schedule for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:715-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Oh HS, Lee DH, Seo JY, Cho YR, Kim N, Jeoung SH, Kim JW, Hwang JH, Park YS, Lee SH. Ten-day sequential therapy is more effective than proton pump inhibitor-based therapy in Korea: a prospective, randomized study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:504-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kwon JH, Lee DH, Song BJ, Lee JW, Kim JJ, Park YS, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Lee SH. Ten-day sequential therapy as first-line treatment for Helicobacter pylori infection in Korea: a retrospective study. Helicobacter. 2010;15:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Park HG, Jung MK, Jung JT, Kwon JG, Kim EY, Seo HE, Lee JH, Yang CH, Kim ES, Cho KB. Randomised clinical trial: a comparative study of 10-day sequential therapy with 7-day standard triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection in naïve patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:56-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Houben MH, van de Beek D, Hensen EF, de Craen AJ, Rauws EA, Tytgat GN. A systematic review of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy--the impact of antimicrobial resistance on eradication rates. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1047-1055. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mégraud F, Lamouliatte H. Review article: the treatment of refractory Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:1333-1343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mégraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance, and advances in testing. Gut. 2004;53:1374-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 607] [Cited by in RCA: 681] [Article Influence: 32.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Lee JW, Kim N, Kim JM, Nam RH, Chang H, Kim JY, Shin CM, Park YS, Lee DH, Jung HC. Prevalence of primary and secondary antimicrobial resistance of Helicobacter pylori in Korea from 2003 through 2012. Helicobacter. 2013;18:206-214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a pooled-data analysis. Gut. 2007;56:1353-1357. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Murakami K, Fujioka T, Okimoto T, Sato R, Kodama M, Nasu M. Drug combinations with amoxycillin reduce selection of clarithromycin resistance during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sánchez-Delgado J, Calvet X, Bujanda L, Gisbert JP, Titó L, Castro M. Ten-day sequential treatment for Helicobacter pylori eradication in clinical practice. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2220-2223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, Opekun AR, Kuo CH, Wu IC, Wang SS, Chen A, Hung WC, Graham DY. Sequential and concomitant therapy with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:36-41.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim YS, Kim SJ, Yoon JH, Suk KT, Kim JB, Kim DJ, Kim DY, Min HJ, Park SH, Shin WG. Randomised clinical trial: the efficacy of a 10-day sequential therapy vs. a 14-day standard proton pump inhibitor-based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori in Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:1098-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lim JH, Lee DH, Choi C, Lee ST, Kim N, Jeong SH, Kim JW, Hwang JH, Park YS, Lee SH. Clinical outcomes of two-week sequential and concomitant therapies for Helicobacter pylori eradication: a randomized pilot study. Helicobacter. 2013;18:180-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miyachi H, Miki I, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Matsumoto Y, Toyoda M, Mitani T, Morita Y, Tamura T, Kinoshita S. Primary levofloxacin resistance and gyrA/B mutations among Helicobacter pylori in Japan. Helicobacter. 2006;11:243-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McMahon BJ, Hennessy TW, Bensler JM, Bruden DL, Parkinson AJ, Morris JM, Reasonover AL, Hurlburt DA, Bruce MG, Sacco F. The relationship among previous antimicrobial use, antimicrobial resistance, and treatment outcomes for Helicobacter pylori infections. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:463-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Watanabe Y, Aoyama N, Shirasaka D, Maekawa S, Kuroda K, Miki I, Kachi M, Fukuda M, Wambura C, Tamura T. Levofloxacin based triple therapy as a second-line treatment after failure of helicobacter pylori eradication with standard triple therapy. Dig Liver Dis. 2003;35:711-715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wong WM, Gu Q, Chu KM, Yee YK, Fung FM, Tong TS, Chan AO, Lai KC, Chan CK, Wong BC. Lansoprazole, levofloxacin and amoxicillin triple therapy vs. quadruple therapy as second-line treatment of resistant Helicobacter pylori infection. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee JH, Hong SP, Kwon CI, Phyun LH, Lee BS, Song HU, Ko KH, Hwang SG, Park PW, Rim KS. [The efficacy of levofloxacin based triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;48:19-24. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Kang MS, Park DI, Yun JW, Oh SY, Yoo TW, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK. [Levofloxacin-azithromycin combined triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication]. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2006;47:30-36. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Tsay FW, Tseng HH, Hsu PI, Wang KM, Lee CC, Chang SN, Wang HM, Yu HC, Chen WC, Peng NJ. Sequential therapy achieves a higher eradication rate than standard triple therapy in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:498-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Perri F, Villani MR, Festa V, Quitadamo M, Andriulli A. Predictors of failure of Helicobacter pylori eradication with the standard ‘Maastricht triple therapy’. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:1023-1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Liang SY, Mackowiak PA. Infections in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:441-56, viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |