Published online Apr 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4954

Peer-review started: October 15, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: November 26, 2014

Accepted: January 16, 2015

Article in press: January 16, 2015

Published online: April 28, 2015

Processing time: 194 Days and 8.7 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the incidence and clinical characteristics of gastric cancer (GC) in peptic ulcer patients with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection.

METHODS: Between January 2003 and December 2013, the medical records of patients diagnosed with GC were retrospectively reviewed. Those with previous gastric ulcer (GU) and H. pylori infection were assigned to the HpGU-GC group (n = 86) and those with previous duodenal ulcer (DU) disease and H. pylori infection were assigned to the HpDU-GC group (n = 35). The incidence rates of GC in the HpGU-GC and HpDU-GC groups were analyzed. Data on demographics (age, gender, peptic ulcer complications and cancer treatment), GC clinical characteristics [location, pathological diagnosis, differentiation, T stage, Lauren’s classification, atrophy of surrounding mucosa and intestinal metaplasia (IM)], outcome of eradication therapy for H. pylori infection, esophagogastroduodenoscopy number and the duration until GC onset were reviewed. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify factors influencing GC development. The relative risk of GC was evaluated using a Cox proportional hazards model.

RESULTS: The incidence rates of GC were 3.60% (86/2387) in the HpGU-GC group and 1.66% (35/2098) in the HpDU-GC group. The annual incidence was 0.41% in the HpGU-GC group and 0.11% in the HpDU-GC group. The rates of moderate-to-severe atrophy of the surrounding mucosa and IM were higher in the HpGU-GC group than in the HpDU-GC group (86% vs 34.3%, respectively, and 61.6% vs 14.3%, respectively, P < 0.05). In the univariate analysis, atrophy of surrounding mucosa, IM and eradication therapy for H. pylori infection were significantly associated with the development of GC (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference in the prognosis of GC patients between the HpGU-GC and HpDU-GC groups (P = 0.347). The relative risk of GC development in the HpGU-GC group compared to that of the HpDU-GC group, after correction for age and gender, was 1.71 (95%CI: 1.09-2.70; P = 0.02).

CONCLUSION: GU patients with H. pylori infection had higher GC incidence rates and relative risks. Atrophy of surrounding mucosa, IM and eradication therapy were associated with GC.

Core tip: This is the first study to investigate gastric cancer (GC) incidence in peptic ulcer patients with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection and to compare GC clinical characteristics between patients with gastric ulcer (GU) and duodenal ulcer (DU) disease. The GC incidence rate and relative risk in GU patients with H. pylori infection were higher than in DU patients. The H. pylori eradication rate was lower in GU than in DU patients, although the success rate of therapy was lower than the failure rate in both groups. Atrophy of surrounding mucosa, intestinal metaplasia and H. pylori eradication therapy were significantly associated with GC.

-

Citation: Hwang JJ, Lee DH, Lee AR, Yoon H, Shin CM, Park YS, Kim N. Characteristics of gastric cancer in peptic ulcer patients with

Helicobacter pylori infection. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(16): 4954-4960 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i16/4954.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4954

Following the establishment of the association between Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) and chronic gastritis in 1983 by Warren and Marshall[1], this association has been implicated in numerous gastrointestinal diseases. This spiral-shaped, gram-negative bacterium remains the most common source of chronic bacterial infection in humans worldwide. In 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer classified H. pylori as a group 1 carcinogen[2], a definite cause of cancer in humans. This classification was based on epidemiological studies which demonstrated that individuals infected with H. pylori are at an increased risk of distal gastric adenocarcinoma[3]. Gastric cancer (GC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the world[4]. H. pylori infection has also been implicated in peptic ulcer diseases[5,6]. Therefore, it is possible that patients with peptic ulcers and H. pylori infection have a high risk of GC development. However, a number of studies have shown that while patients with gastric ulcer (GU) disease have a high risk of GC, those with duodenal ulcer (DU) disease do not[7-10]. Recently, this paradoxical phenomenon has been described in several studies[7-10].

Post-H. pylori infection clinical prognoses are associated with increased acid secretion levels and inflammation extent and severity[11]. DU disease is typically associated with antral-predominant gastritis that leads to normal or increased acid secretion[12,13]. In contrast, GU disease is associated with corpus-predominant gastritis, which provides information on the extent and severity of gastritis, atrophy and acid secretion. GC is associated with pangastritis, which ultimately results in progression from normal gastric mucosa to intestinal metaplasia (IM) and little to no acid secretion[11]. The incidence of GC increases with the extent of gastritis and the severity[13-15], such that GU disease and GC form one axis (e.g., atrophic pangastritis) and DU disease forms a second axis (antral-predominant or corpus-sparing gastritis). Thus, GU disease and GC can evolve from DU disease but the opposite cannot occur. A prospective Japanese study that followed 275 DU patients found that while none of the DU patients developed GC, 3.4% of 297 GU patients did develop GC[8]. A recent retrospective study of 37 patients with both DU disease and GC reported clinical and pathological features relevant to both diseases[16]. However, while there have been many studies on GC development in either patients with H. pylori infection or DU disease, there have been no studies on GC development in peptic ulcer (either GU or DU) patients with H. pylori infection.

The aim of this study was to investigate the incidence of GC development in peptic ulcer patients with H. pylori infection and to compare the clinical characteristics of GC between GU and DU patients with H. pylori infection.

This study was conducted at Seoul National University Bundang Hospital between January 2003 and December 2013. The medical records of patients newly diagnosed with GC were retrospectively reviewed. The patients selected for the study met the following inclusion criteria: (1) age older than 18 years; (2) a previous diagnosis of peptic ulcer (GU or DU) disease by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD); and (3) a diagnosis of H. pylori infection by EGD concomitant with diagnosis of peptic ulcer disease. The exclusion criteria were the following: (1) age younger than 18 years; (2) previous endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) or gastric surgery for GC; (3) a previous history of H. pylori eradication; (4) a history of medication with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in the 4 wk preceding the EGD; and (5) a diagnosis of GC within 1 year of study enrollment. The patients participating in the study were advised to undergo EGD every year in order to confirm the occurrence of recurrent peptic ulcer disease and the development of GC.

EGD was performed annually on the enrolled patients. A histopathological exam was performed simultaneously via endoscopic biopsy. The presence of H. pylori infection was defined by at least one of the following criteria: (1) a positive 13C-urea breath test; (2) histological evidence of H. pylori by modified Giemsa staining in the lesser and greater curvatures of the body and antrum; and (3) a positive rapid urease test (CLOtest; Delta West, Bentley, Australia) by gastric mucosal biopsy from the lesser curvature of the body and antrum. All of the patients with H. pylori infection received standard first-line triple therapy [1 g amoxicillin twice a day (b.i.d), 500 mg clarithromycin b.i.d. and 20 mg rabeprazole (or 40 mg esomeprazole) b.i.d. for 7 d]. Patients that failed first-line triple therapy received rescue therapy until the eradication treatment was successful.

Pathological stage determinations were made using the American Joint Committee on Cancer TNM classification system and the 6th edition of the International Union Against Cancer[17]. The histological types and tumor differentiation were identified using Lauren’s classification[18] and the World Health Organization criteria[19], respectively. The cancer location was determined according to the Japanese Classification of Gastric Cancer[20].

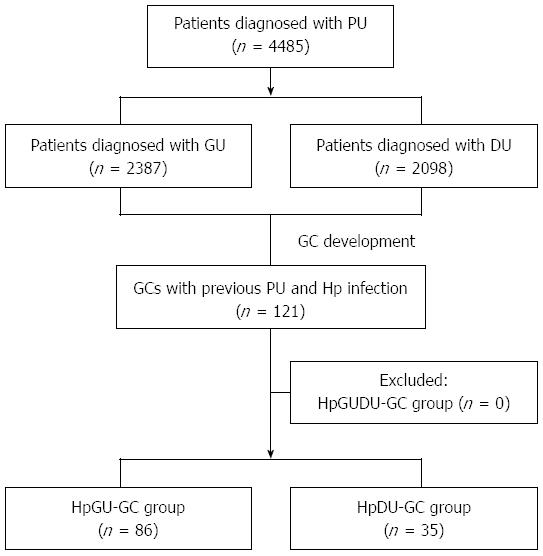

The enrolled patients were classified into two groups. Patients who were newly diagnosed with GC and those who were previously diagnosed with GU and H. pylori infection were assigned to the HpGU-GC group and patients who were newly diagnosed with GC and those diagnosed previously with DU and H. pylori infection were assigned to the HpDU-GC group. Patients with GU and DU disease and H. pylori infection (the HpGUDU-GC group) were excluded from the analysis because none of them developed GC. Data on demographics (age, gender, peptic ulcer complications and cancer treatment), GC clinical characteristics (location, pathological diagnosis, differentiation, T stage, Lauren’s classification, atrophy of surrounding mucosa and IM), outcome of eradication therapy for H. pylori infection, EGD number and the duration until GC onset were recorded. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Bundang Hospital (IRB number: B-1408/262-108).

The statistical analysis was performed using the Predictive Analytics Software 20.0 version for Windows package (SPSS Inc., IBM, Chicago, IL, United States). The mean ± SD for the quantitative variables were calculated. The student’s t-test was used to evaluate continuous variables and the chi square and Fisher’s exact tests were utilized to assess non-continuous variables. Additionally, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to evaluate independent factors that determine GC development. A Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to calculate the relative risk (corrected for age and gender) for each group. A P value of less than 0.05 was defined as clinically significant.

A schematic diagram of the study is shown in Figure 1. Between 2003 and 2013, 4485 patients were diagnosed with peptic ulcer disease. Of these patients, 2387 had GU and 2098 patients had DU disease. A total 121 of the patients were newly diagnosed with GC and previously with a peptic ulcer (GU or DU) with H. pylori infection. No patient previously diagnosed with GU and DU disease as well as H. pylori infection was newly diagnosed with GC. Of the 121 patients newly diagnosed with GC, 86 were from the HpGU-GC group and 35 were from the HpDU-GC group. The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are provided in Table 1. The average ages of the HpGU-GC and HpDU-GC groups were 62.2 ± 10.1 and 62.5 ± 13.2 years, respectively (P = 0.412). There were no statistically significant differences in gender distribution or peptic ulcer complications (Table 1). Three patients experienced bleeding, a complication of peptic ulcers, although it spontaneously stopped without endoscopic hemostatic therapy and the patients were treated medically with PPIs. In terms of GC treatment, the rates of ESD and surgery were 58.1% (50/86) and 41.9% (36/86), respectively, in the HpGU-GC group and 51.4% (18/35) and 48.6% (17/35), respectively, in the HpDU-GC group. The inter-group differences, however, were not statistically significant (Table 1).

| HpGU-GC group(n = 86) | HpDU-GC group(n = 35) | P value | |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 62.2 ± 10.1 | 62.5 ± 13.2 | 0.412 |

| Gender | 0.935 | ||

| Male | 68 (79.1) | 28 (80.0) | |

| Female | 18 (20.9) | 7 (20.0) | |

| Complication of peptic ulcer | 3 (3.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.463 |

| Treatment of cancer | 0.728 | ||

| ESD | 50 (58.1) | 18 (51.4) | |

| Surgery | 36 (41.9) | 17 (48.6) |

In the HpGU-GC group, 86 patients (3.6%) developed GC during the follow-up period, whereas in the HpDU-GC group, 35 (1.66%) developed GC. The annual incidence was 0.41% in the HpGU-GC group and 0.11% in the HpDU-GC group. The GC characteristics are listed in Table 2. The rate of early GC was higher than that of advanced gastric cancer in both groups (HpGU-GC: 88.4% vs 11.6%; HpDU-GC: 80.0% vs 20.0%). The most common location of GC in the HpGU-GC group was the middle portion (52.3%) and the lower portion (65.7%) in the HpDU-GC group. Adenocarcinoma and intestinal type were, by World Health Organization criteria and Lauren’s classification, the most common pathological features of GC in both groups, although the differences were not statistically significant. Pathologically, well-differentiated GCs were more common in the HpGU-GC (48.8%) and HpDU-GC (40.0%) groups but this was not statistically significant (Table 2). In both groups, the GC involvement was within the lamina propria (defined as the T1a stage), which was statistically significant (P = 0.007). The rate of moderate-to-severe atrophy of surrounding mucosa was 86% in the HpGU-GC group and 34.3% in the HpDU-GC group (P = 0.041). The rate of moderate-to-severe IM was 61.6% in the HpGU-GC group and 14.3% in the HpDU-GC group (P = 0.037). Notably, both of these rates were significantly higher in the HpGU-GC group than in the HpDU-GC group (P < 0.05). The eradication rate of H. pylori infection was 40.6% in the HpGU-GC group and 48.6% in the HpDU-GC group. The H. pylori-eradication rate in the HpDU-GC group was significantly higher than in the HpGU-GC group. However, the success rate of eradication therapy was lower than the failure rate in both groups (P = 0.039). The mean EGD from peptic ulcer diagnosis to GC development was 5.5 ± 3.2 in the HpGU-GC group and 4.9 ± 3.5 in the HpDU-GC group (P = 0.076). The mean time from peptic ulcer diagnosis to GC development was 3.5 ± 2.4 years in the HpGU-GC group and 3.1 ± 2.7 years in the HpDU-GC group (P = 0.09). In the univariate analysis, atrophy of surrounding mucosa, IM and eradication therapy for H. pylori infection were significantly associated with development of GC (P < 0.05; Table 2).

| HpGU-GC(n = 86) | HpDU-GC(n = 35) | P value | Univariateanalysis | |

| Annual incidence (yr) | 0.41% | 0.11% | ||

| Type of cancer | 0.534 | - | ||

| Early gastric cancer | 76 (88.4) | 28 (80.0) | ||

| Advanced gastric cancer | 10 (11.6) | 7 (20.0) | ||

| Location of cancer | 0.341 | - | ||

| Upper | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Middle | 45 (52.3) | 12 (34.3) | ||

| Lower | 40 (46.5) | 23 (65.7) | ||

| Diagnosis of cancer | 0.515 | - | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 77 (89.5) | 28 (80.0) | ||

| Signet ring cell carcinoma | 7 (8.1) | 5 (14.2) | ||

| Mixed carcinoma | 2 (2.4) | 2 (5.8) | ||

| Differentiation of cancer | 0.134 | - | ||

| Well-differentiated | 42 (48.8) | 14 (40.0) | ||

| Moderate-differentiated | 31 (36.0) | 11 (31.4) | ||

| Poor-differentiated | 13 (15.2) | 10 (28.6) | ||

| T-stage of cancer | 0.007 | - | ||

| T1a | 59 (68.6) | 16 (45.7) | ||

| T1b | 16 (18.6) | 12 (34.2) | ||

| T2 | 10 (11.6) | 3 (8.7) | ||

| T3 | 1 (1.2) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| T4 | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.4) | ||

| Lauren’s classification | 0.083 | - | ||

| Intestinal type | 74 (86.0) | 23 (65.7) | ||

| Diffuse type | 10 (11.6) | 12 (34.3) | ||

| Mixed type | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Atrophy of surrounding mucosa | 0.041 | 0.038 | ||

| Non-mild | 12 (14.0) | 23 (65.7) | ||

| Moderate-severe | 74 (86.0) | 12 (34.3) | ||

| Intestinal metaplasia | 0.037 | 0.032 | ||

| Non-mild | 33 (38.4) | 30 (85.7) | ||

| Moderate-severe | 53 (61.6) | 5 (14.3) | ||

| H. pylori eradication | 0.039 | 0.041 | ||

| Success | 35 (40.6) | 17 (48.6) | ||

| Failure | 51 (59.4) | 18 (51.4) | ||

| Mean number of endoscopy until GC onset, mean ± SD | 5.5 ± 3.2 | 4.9 ± 3.5 | 0.076 | - |

| Mean time until GC onset (yr) | 3.5 ± 2.4 | 3.1 ± 2.7 | 0.09 | - |

Table 3 shows the GC prognoses for the two groups. The number of patients that had a recurrence of GC after ESD or surgery during the follow-up period was 6 (7.0%) in the HpGU-GC group and 2 (5.7%) in the HpDU-GC group, although this difference was not statistically significant. The end-of-study survival rate was 80.2% in the HpGU-GC group and 80.0% in the HpDU-GC group but the difference was not statistically significant (Table 3). The relative risk of GC development of the HpGU-GC group compared to that of the HpDU-GC group, as corrected for age and gender, was 1.71 (95%CI: 1.09-2.70, P = 0.02) according to a Cox proportional hazards model (Table 4).

| HpGU-GC group(n = 86) | HpDU-GC group (n = 35) | P value | |

| Recurrence of cancer | 6 (7.0) | 2 (5.7) | 0.965 |

| Prognosis of cancer | 0.347 | ||

| Alive | 69 (80.2) | 28 (80.0) | |

| Death | 15 (17.5) | 6 (17.2) | |

| Unknown | 2 (2.3) | 1 (2.8) |

| Relative risk | 95%CI | P value | |

| Group | |||

| HpDU-GC | 1.00 | - | - |

| HpGU-GC | 1.71 | 1.09-2.70 | 0.02 |

Patients with H. pylori infection have a high risk of GC[2,3]. In fact, a recent review indicated that 2 million cases of cancer each year worldwide could be attributed to H. pylori, a key infectious agent leading to GC[21]. The EUROGAST study on diverse populations found a 6-fold increase in the risk of gastric adenocarcinoma development for patients with H. pylori infection compared to patients that were not infected[22]. There is a still much greater risk of adenocarcinoma in H. pylori-infected individuals younger than 30 years of age[23]. H. pylori infection has been associated with increases in both intestinal and diffuse types of gastric adenocarcinoma[23,24]. However, there appears to be a difference in the locations of gastric adenocarcinoma in H. pylori-infected patients. Distal gastric adenocarcinoma is much more likely to develop in H. pylori-infected patients than gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma[25]. In any case, despite the well-established and clear association between persistent H. pylori infection and gastric adenocarcinoma, only a small percentage of infected individuals will develop malignancies. This is likely due to a myriad of external and environmental factors that are believed to affect the disease course and progression. Factors that promote malignancy development include certain dietary influences such as high salt intake, red and processed meat consumption, and nitrosamines, while factors that can reduce the risk of malignancy include diets that are high in fresh foods and vegetables[26,27].

Hansson et al[7] investigated the risk of GC among patients with peptic ulcer disease in a Swedish population-based study. The authors reported that GC risk leveled off and stabilized after the first 3 and 2 years of GU and DU, respectively. GU patients had a relative risk of 1.8 throughout the follow-up period, whereas the relative risk for DU patients was only 0.6. Female patients and patients who were younger than 50 years old were found to have a higher risk of GC than an age- and gender-matched background population. In the present study, the relative risk of the HpGU-GC group compared to that of the HpDU-GC group (as adjusted for age and gender using a Cox proportional hazards model) was 1.71 (95%CI: 1.09-2.70, P = 0.02), without inclusion of a reference to the success of H. pylori eradication therapy. This rate was very similar to the value of 1.8 reported for GU patients in the study by Hansson et al[7]. Patient age and gender were not associated with GC development.

Uemura et al[8] evaluated a large Japanese cohort with H. pylori infection over the course of a 5-year follow-up period and reported that even although all of the DU patients had H. pylori infection, none developed GC. On the other hand, the rate of H. pylori infection was 3.4% in GU patients but GC occurs in 5% of GU patients with H. pylori infection. These inconsistent results may be explained by the lower rate of mucosal atrophy in DU compared to GU patients.

In the present study, 86/2387 GU patients with H. pylori infection developed GC, representing an annual incidence rate of 0.41%. In contrast, only 35/2098 DU patients with H. pylori infection developed GC, corresponding to an annual incidence rate of 0.11%. This is markedly lower than that of GU patients and is consistent with a study by Uemura et al[8]. The most common site involved in both groups was the lamina propria (defined as stage T1a). This may reflect the increased possibility of early diagnosis of GC with regular EGD. The incidence rate and relative risk of GC development in GU patients with H. pylori infection were significantly higher than in DU patients with H. pylori infection. The H. pylori eradication rate in GU patients was significantly lower than in DU patients, although the success rate of eradication therapy was lower than the failure rate in both patient groups. This finding might reflect the possibility of an association between the high incidence rate, relative risk of GC development and low H. pylori eradication rate in GU patients with H. pylori infection.

One of the most important factors affecting variable patient outcomes is the extent of gastritis. GU and GC are associated with atrophic pangastritis and DU is associated with non-atrophic antral-predominant gastritis[13-15]. In the present study, the rates of moderate-to-severe atrophy of the surrounding mucosa and IM were significantly higher in the HpGU-GC group than in the HpDU-GC group. These results are similar to those of a previous study which showed that the severity and extent of gastritis are important factors that determine disease prognosis after H. pylori infection[28]. Because intestinal crypts replace the specialized glands of atrophic gastritis in IM, it was thought that atrophic gastritis and IM were the same entity[29].

Recent studies have indicated that gastric carcinogenesis consists of multiple processes. IM, in accordance with the updated Sydney system, is considered to be an important step[30]. It is more closely associated with GC than atrophic gastritis as a premalignant lesion. The odds ratios reported for GC in superficial gastritis and atrophic gastritis according to IM severity are 29.3 and 17.4, respectively[31]. In another study, the annual incidence of GC was determined to be higher in patients with IM (0.25%) than in patients with atrophic gastritis (0.1%)[32]. Results such as these might constitute evidence supporting the multiple processes of gastric carcinogenesis identified by Correa[33]. Indeed, IM can be an important predictor of GC risk[34].

In a study that compared the histopathological features of GC patients with those of a healthy control population, the frequency of IM was higher in GC patients than in the healthy control population, even although the severity and extent of atrophic gastritis were similar in both groups[35]. These results suggest that for a population in which progression from atrophic mucosa to IM is possible, there is a higher risk of GC[35]. In the present study, the rates of moderate-to-severe atrophy of surrounding mucosa and IM were significantly higher in the HpGU-GC group than in the HpDU-GC group. Furthermore, atrophy of the surrounding mucosa and IM were significantly associated with GC development in a univariate analysis. These results were similar to those from previous studies[30-35], regardless of the success of H. pylori eradication therapy.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to have investigated the incidence of GC development in peptic ulcer patients with H. pylori infection and to have compared the clinical characteristics of GC between GU and DU patients. However, there are several limitations. Firstly, because this was a retrospective study based on patients with peptic ulcer diseases and H. pylori infection, we could not investigate the causes of failures in H. pylori eradication therapy, histories of drug intake (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug or aspirin) and the proportion of patients with H. pylori infection at the time of diagnosis with GU and DU disease. Secondly, we could not evaluate the association of the incidence of developing GC in both GU and DU patients and the success or failure H. pylori eradication. Selection bias may also exist. Thirdly, relevant genetic factors were not investigated. Fourthly, we did not analyze the relative risk of patients with peptic ulcer disease without H. pylori infection.

In summary, the incidence rate and relative risk of GC development in GU patients with H. pylori infection were significantly higher than in DU patients with H. pylori infection. The H. pylori eradication rate in GU patients was significantly lower than in DU patients, although the success rate of eradication therapy was lower than the failure rate in both groups of patients. Atrophy of the surrounding mucosa, IM and eradication therapy for H. pylori infection were significantly associated with GC development.

It is well established that Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is a strong risk factor for gastric cancer (GC). H. pylori infection has also been implicated in peptic ulcer diseases. There is an urgent need to elucidate the relationship between GC, peptic ulcers and H. pylori infection.

There is controversy as to whether gastric and duodenal ulcers (DUs) have similar effects on GC development. Several animal and human studies have suggested that H. pylori infection is a risk factor for GC development.

This is the first study to investigate the incidence of GC development in peptic ulcer patients with H. pylori infection and to compare the clinical characteristics of GC between gastric ulcer (GU) and DU patients. The incidence rate and relative risk of GC development in GU patients with H. pylori infection were significantly higher than in DU patients with H. pylori infection. The H. pylori eradication rate in GU patients was significantly lower than in DU patients, although the success rate of eradication therapy was lower than the failure rate in both groups of patients. Atrophy of surrounding mucosa, IM and eradication therapy for H. pylori infection were significantly associated with GC development.

This study urges clinicians to confirm H. pylori infection and to start eradication therapy to prevent GC development in patients with peptic ulcers.

H. pylori is a bacterium found in the stomach. It is linked to the development of gastritis, peptic ulcers and stomach cancer. To prevent recurrence in patients with these diseases, it is necessary to eradicate bacterial infections with H. pylori.

This study evaluated the incidence of GC development in patients with peptic GU and/or DU disease that were positive for H. pylori infection. The incidence rate and relative risk of GC development in patients with GUs were significantly higher than in patients with DUs. The findings are reasonable and make sense.

P- Reviewer: Dore MP, Gururatsakul M S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Roemmele A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | McColl KE. Clinical practice. Helicobacter pylori infection. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1597-1604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 36.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Parsonnet J, Friedman GD, Vandersteen DP, Chang Y, Vogelman JH, Orentreich N, Sibley RK. Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of gastric carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1127-1131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2805] [Cited by in RCA: 2739] [Article Influence: 80.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Stewart BW, Kleihues P. World cancer report. Lyon: IARC Press 2003; 194. |

| 4. | Parsonnet J, Harris RA, Hack HM, Owens DK. Modelling cost-effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori screening to prevent gastric cancer: a mandate for clinical trials. Lancet. 1996;348:150-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hopkins RJ, Girardi LS, Turney EA. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori eradication and reduced duodenal and gastric ulcer recurrence: a review. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1244-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 373] [Cited by in RCA: 354] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rosenstock S, Jørgensen T, Bonnevie O, Andersen L. Risk factors for peptic ulcer disease: a population based prospective cohort study comprising 2416 Danish adults. Gut. 2003;52:186-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hansson LE, Nyrén O, Hsing AW, Bergström R, Josefsson S, Chow WH, Fraumeni JF, Adami HO. The risk of stomach cancer in patients with gastric or duodenal ulcer disease. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:242-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784-789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3126] [Cited by in RCA: 3182] [Article Influence: 132.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Molloy RM, Sonnenberg A. Relation between gastric cancer and previous peptic ulcer disease. Gut. 1997;40:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Take S, Mizuno M, Ishiki K, Nagahara Y, Yoshida T, Yokota K, Oguma K, Okada H, Shiratori Y. The effect of eradicating helicobacter pylori on the development of gastric cancer in patients with peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:1037-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection in the pathogenesis of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer: a model. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:1983-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | el-Omar EM, Penman ID, Ardill JE, Chittajallu RS, Howie C, McColl KE. Helicobacter pylori infection and abnormalities of acid secretion in patients with duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:681-691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 356] [Cited by in RCA: 328] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Graham DY. Campylobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:615-625. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lauwers G, Carneiro F, Graham DY, Curado MP, Franceschi S, Hattori T, Montgomery E, Tematsu M. Gastric Cancer. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC 2010; 48-58. |

| 15. | Graham DY, Asaka M. Eradication of gastric cancer and more efficient gastric cancer surveillance in Japan: two peas in a pod. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhao L, Shen ZX, Luo HS, Yu JP. Clinical investigation on coexisting of duodenal ulcer and gastric cancer in China. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:1153-1156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sobin LH, Wittekind C. TNM Classification of Malignant Tumors. 6th ed. New York, NY: Wiley-Liss 2002; . |

| 18. | Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: Diffuse and so-called intestinal-type carcinoma. An attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31-49. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hamilton SR, Aaltonen LA, editors . World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Pathology and Genetics, Tumours of the Digestive System. Lyon, France: IARC Press 2000; . |

| 20. | Japanese Gastric Cancer A. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma - 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10-24. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2009] [Cited by in RCA: 1942] [Article Influence: 71.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1717] [Article Influence: 132.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | An international association between Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer. The EUROGAST Study Group. Lancet. 1993;341:1359-1362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 842] [Cited by in RCA: 742] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Huang JQ, Sridhar S, Chen Y, Hunt RH. Meta-analysis of the relationship between Helicobacter pylori seropositivity and gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 625] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hansson LR, Engstrand L, Nyrén O, Lindgren A. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in subtypes of gastric cancer. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:885-888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kamada T, Kurose H, Yamanaka Y, Manabe N, Kusunoki H, Shiotani A, Inoue K, Hata J, Matsumoto H, Akiyama T. Relationship between gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma and Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan. Digestion. 2012;85:256-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tsugane S, Tei Y, Takahashi T, Watanabe S, Sugano K. Salty food intake and risk of Helicobacter pylori infection. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1994;85:474-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | González CA, López-Carrillo L. Helicobacter pylori, nutrition and smoking interactions: their impact in gastric carcinogenesis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Graham DY, Lu H, Yamaoka Y. African, Asian or Indian enigma, the East Asian Helicobacter pylori: facts or medical myths. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Cheli R, Santi L, Ciancamerla G, Canciani G. A clinical and statistical follow-up study of atrophic gastritis. Am J Dig Dis. 1973;18:1061-1065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | de Vries AC, Meijer GA, Looman CW, Casparie MK, Hansen BE, van Grieken NC, Kuipers EJ. Epidemiological trends of pre-malignant gastric lesions: a long-term nationwide study in the Netherlands. Gut. 2007;56:1665-1670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | You WC, Li JY, Blot WJ, Chang YS, Jin ML, Gail MH, Zhang L, Liu WD, Ma JL, Hu YR. Evolution of precancerous lesions in a rural Chinese population at high risk of gastric cancer. Int J Cancer. 1999;83:615-619. [PubMed] |

| 32. | de Vries AC, van Grieken NC, Looman CW, Casparie MK, de Vries E, Meijer GA, Kuipers EJ. Gastric cancer risk in patients with premalignant gastric lesions: a nationwide cohort study in the Netherlands. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:945-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 483] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 34.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Correa P. Human gastric carcinogenesis: a multistep and multifactorial process--First American Cancer Society Award Lecture on Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention. Cancer Res. 1992;52:6735-6740. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Meining A, Bayerdörffer E, Müller P, Miehlke S, Lehn N, Hölzel D, Hatz R, Stolte M. Gastric carcinoma risk index in patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Virchows Arch. 1998;432:311-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Shimoyama T, Fukuda S, Tanaka M, Nakaji S, Munakata A. Evaluation of the applicability of the gastric carcinoma risk index for intestinal type cancer in Japanese patients infected with Helicobacter pylori. Virchows Arch. 2000;436:585-587. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |