Published online Apr 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4925

Peer-review started: October 27, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 17, 2014

Accepted: February 5, 2015

Article in press: February 5, 2015

Published online: April 28, 2015

Processing time: 186 Days and 1.2 Hours

AIM: To determine the long-term hepatobiliary complications of alveolar echinococcosis (AE) and treatment options using interventional methods.

METHODS: Included in the study were 35 patients with AE enrolled in the Echinococcus Multilocularis Data Bank of the University Hospital of Ulm. Patients underwent endoscopic intervention for treatment of hepatobiliary complications between 1979 and 2012. Patients’ epidemiologic data, clinical symptoms, and indications for the intervention, the type of intervention and any additional procedures, hepatic laboratory parameters (pre- and post-intervention), medication and surgical treatment (pre- and post-intervention), as well as complications associated with the intervention and patients‘ subsequent clinical courses were analyzed. In order to compare patients with AE with and without history of intervention, data from an additional 322 patients with AE who had not experienced hepatobiliary complications and had not undergone endoscopic intervention were retrieved and analyzed.

RESULTS: Included in the study were 22 male and 13 female patients whose average age at first diagnosis was 48.1 years and 52.7 years at the time of intervention. The average time elapsed between first diagnosis and onset of hepatobiliary complications was 3.7 years. The most common symptoms were jaundice, abdominal pains, and weight loss. The number of interventions per patient ranged from one to ten. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was most frequently performed in combination with stent placement (82.9%), followed by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage (31.4%) and ERCP without stent placement (22.9%). In 14.3% of cases, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography was performed. A total of eight patients received a biliary stent. A comparison of biochemical hepatic function parameters at first diagnosis between patients who had or had not undergone intervention revealed that these were significantly elevated in six patients who had undergone intervention. Complications (cholangitis, pancreatitis) occurred in six patients during and in 12 patients following the intervention. The average survival following onset of hepatobiliary complications was 8.8 years.

CONCLUSION: Hepatobiliary complications occur in about 10% of patients. A significant increase in hepatic transaminase concentrations facilitates the diagnosis. Interventional methods represent viable management options.

Core tip: Approximately 10% of patients with alveolar echinococcosis experience hepatobiliary complications that occur on average 3.7 years (range: 0-41 years) following first diagnosis. Elevated hepatic transaminases in association with jaundice, abdominal pain, and weight loss are typical symptoms facilitating the diagnosis. Interventional endoscopic methods represent important options in these patients’ management. Even in cases of repeated interventions, the rates of complications and treatment-associated mortality are low. The average survival following onset of hepatobiliary complications and interventional treatment stands at 8.8 years.

- Citation: Graeter T, Ehing F, Oeztuerk S, Mason RA, Haenle MM, Kratzer W, Seufferlein T, Gruener B. Hepatobiliary complications of alveolar echinococcosis: A long-term follow-up study. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(16): 4925-4932

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i16/4925.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4925

Alveolar echinococcosis (AE) is a rare but potentially life-threatening parasitic disease that results from infection with the larval stage of Echinococcus multilocularis[1-3]. Worldwide, the range of the parasite is limited to cold and temperate regions of the northern hemisphere[4]. Although its incidence in endemic regions is generally low (0.03-1.20 per 100000 persons)[1,5], more recent studies suggest that the endemic regions of E. multilocularis are larger than previously believed. In addition, increased fox (Vulpes vulpes) populations, including in urban areas, have been reported[6-8], with an associated increased infection risk for humans[6]. Despite abundant clinical resources and technical advances, the diagnosis of AE in infected individuals, especially among inexperienced clinicians, remains challenging. With delayed diagnosis, therapy often begins in a late stage of the disease, which significantly limits treatment options. A characteristic feature of AE is its tumor-like growth, which may lead to infiltration of neighboring organs[1]. The liver is the first organ to be affected by larval infestation. Hepatic lesions are localized to the right hepatic lobe in seven of ten cases, while in 40%, the liver hilus is additionally affected. Only in two of ten cases are both hepatic lobes infested[9].

Patients are typically asymptomatic during the initial phase of the infection. The first symptoms may include upper abdominal pain and cholestatic jaundice. The incubation time ranges from five to fifteen years[5]. Radical resection of the echinococcal lesion is the only curative therapy. Untreated patients experience a mortality rate of 95% within ten years of first diagnosis[10]. Only early detection serves to increase the rate of curative resection[11], which is confirmed on the basis of imaging methods and serologic markers[12]. Complications such as biliary obstruction, portal hypertension, and bleeding esophageal varices have been described in advanced disease stages and are ascribed to the invasive growth of the E. multilocularis lesion in the liver[13].

Biliary complications such as intrabiliary rupture in combination with obstructive jaundice in cystic echinococcosis, which is caused by E. granulosus, has an incidence of 1%-25% and, in cases of biliary fistulae, can often be effectively treated using endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[14,15]. By contrast, a search of the literature with respect to the use of interventional methods such as ERCP in the treatment of hepatobiliary complications of AE reveals no prospective studies and only a few case studies[13,16] and reports of experience with small numbers of patients[17-20]. A recently published study with 26 cases represents the largest currently available study of patients with hepatobiliary complications in AE[21]. The authors postulate that surgical interventions represent risk factors for the occurrence of such complications. The incidence of biliary complications was reported to be about 30% with an average survival of three years following hepatobiliary complications[21]. The studies by Ozturk et al[16] and Sezgin et al[13] with 13 and 12 patients, respectively, primarily address the main clinical symptoms and changes in laboratory parameters associated with biliary complications. Hilmioglu et al[17] report on six patients and their ERCP results, which they discuss in terms of characteristic cholangiographic findings. Other authors report single cases, such as Gschwantler et al[18] who report on a combined endoscopic and pharmaceutic approach in a patient with rupture of an AE lesion into the bile duct, Koroglu et al[19], who describe the complete disappearance of AE following percutaneous drainage, and Rosenfeld et al[20], who discuss the onset of painless jaundice and the subsequent therapy. Finally, a few authors mention endoscopic and percutaneous interventions as treatment options for patients in whom the risks of surgery are unacceptably high or in whom the total resection of the AE lesion cannot be guaranteed[22-24].

The objective of the study was to describe the clinical and biochemical outcomes of patients with hepatobiliary complications of AE and to determine treatment options using interventional methods.

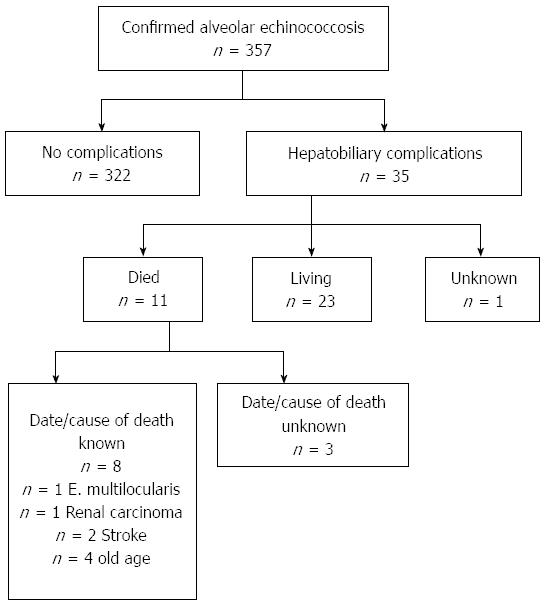

Between 1979 and 2012, AE was diagnosed in 357 patients presenting to the Echinococcosis Specialty Clinic of the University of Ulm. In the present study, we report on 35 patients examined and treated for hepatobiliary complications of AE with interventional methods including ERCP, with or without stent placement, percutaneous transhepatic cholangiodrainage (PTCD), and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). Criteria for inclusion in the study included confirmed diagnosis of AE, use of at least one of the above-mentioned methods for treatment of hepatobiliary complications, and availability of pre- and post-procedure data on laboratory findings, medication, and surgery. Not all patients were diagnosed and treated in our clinic; patients’ records, however, contained reports and discharge summaries from outside institutions. Patient data was derived retrospectively from the Echinococcus Multilocularis Data Bank of the University Hospital of Ulm. Patients’ epidemiologic data, clinical symptoms, and indications for the intervention, the type of intervention and any additional procedures, hepatic laboratory parameters (pre- and post-intervention), medication and surgical treatment (pre- and post-intervention), as well as complications associated with the intervention and patients’ subsequent clinical courses were recorded.

In addition, available discharge summaries, digital patient records, and reports from outside institutions were reviewed with retrospective compilation of information regarding the indication for the intervention, biochemical hepatic function parameters before and after the intervention, type of intervention, and prior treatment and medication. The subsequent clinical courses of these patients through the end of 2012 were analyzed. All data were then compared with the clinical courses of 322 patients without history of hepatobiliary complications and, thus, without intervention with respect to prior treatment (surgery, medication) and laboratory parameters including hepatic function tests. Prior to analysis, all patient data were anonymized.

The study was conducted in conformity to the basic principles of Helsinki Declaration. It was approved by the local ethics committee. We declare that none of the authors of the present study has any competing commercial, personal, political, intellectual or religious interest with respect to the present study.

Data were analyzed using the SAS 9.2 statistical software package (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States). Data were first analyzed descriptively. For quantitative variables, mean, standard deviation, and minimum and maximum values were derived. For qualitative variables, absolute and relative values are given. In order to identify differences between patients with hepatobiliary complications and those without hepatobiliary complications and without intervention, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used for quantitative variables; for qualitative variables, the χ2 test or, when the number of cases was too small, Fisher’s exact test was used. All tests were two-sided. Statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Suemeyra Oeztuerk (BSc) from Department of Internal Medicine I, University Hospital Ulm.

Included in the present study were 35 patients (22 male, 13 female), whose average age at the time of intervention was 52.7 years (range: 18-82 years). Age distribution at the time of intervention showed two peaks, at 70-79 years (25.7%) and 40-49 years (22.9%), with fewer interventions in patients over the age of 80 years (5.7%) and under 20 years (2.9%). The time from first diagnosis to the onset of hepatobiliary complications showed high variability (0-41 years), with an average of 3.7 years. In 65%, this period was less than one year (Figure 1).

The most frequent symptom of hepatobiliary complications was jaundice (54.3%) (Table 1). The total number of interventions performed in any individual case ranged from one to ten; more than one method could have been employed in patients undergoing multiple interventions. ERCP was most frequently performed in combination with stent placement (82.9%). In addition to the intervention, 16 patients underwent additional procedures. A stent was placed in 74.3% of patients (n = 26). Twenty-five patients underwent stent exchange at some point in their clinical course, with only one patient not undergoing exchange. The most frequent reason was cholangitis (n = 7), followed by unsuccessful first attempt (n = 5), and stent occlusion (n = 4).

| Characteristic | Frequency |

| Symptoms1 | |

| Jaundice | 54.3% |

| Abdominal pain | 31.4% |

| Weight loss | 20.0% |

| Indication for intervention1 | |

| Cholestasis | 54.3% |

| Jaundice | 25.7% |

| Stenosis of biliary tract | 17.1% |

| Cholangitis | 11.4% |

| Intervention method1 | |

| ERCP + stent replacement | 82.9% |

| PTCD | 31.4% |

| ERCP without stent replacement | 22.9% |

| MRCP | 14.3% |

| Additional procedures1 | |

| Papillotomy | 68.8% |

| Dilatation of the bile ducts | 50.0% |

| Gallstone extraction | 25.0% |

| Types of stents | |

| Plastic stent | 30.8% |

| Pigtail drainage | 7.7% |

| Metal stent | 3.9% |

| Percutaneous drainage | 3.9% |

| Transhepatic jejunal endless drainage | 3.9% |

| No data | 50.0% |

Of the 35 patients who had undergone a single intervention, 14 (40%) had also been treated surgically, in 12 cases prior to intervention. Procedures included partial resection of the liver (n = 7), curative hemihepatectomy (n = 2), partial resection of the liver following histological confirmation (n = 2), and liver segment resection (n = 1). Antihelminthic pharmacotherapy was administered in 23 patients prior to onset of hepatobiliary complications, including albendazole (n = 14), mebendazole (n = 8), and amphotericin B (n = 1). Eleven patients underwent further treatment following the first intervention, including partial liver resection (n = 1), curative hemihepatectomy (n = 1), and pharmacotherapy with albendazole (n = 9).

In the group of patients who had not experienced hepatobiliary complications, 46.3% (149/322) had undergone surgery, whereas 50.9% (164/322) had not. In the remaining 2.8% of patients (n = 9), it was not possible on the basis of the available records to retrospectively determine whether or not they had undergone surgery. In the group of patients who had undergone a single intervention, 14/35 (40%) also required surgical treatment, whereas 21/35 (60%) patients did not undergo surgery. There was no significant difference in the rate of surgery between the groups with and without hepatobiliary complications.

Non-resectable AE was diagnosed in 63.0% (225/357) of patients, and hepatobiliary complications were reported in 10.7% (24/225) of these. Patients were considered to have non-resectable AE if they were deemed unsuitable for operation or if curative surgery was unfeasible.

A comparison of biochemical hepatic function parameters at the time of first diagnosis, intervention, and post-intervention in six patients revealed that all parameters increased from the point of first diagnosis to intervention and then declined following intervention. In fact, aspartate transaminase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, and total bilirubin concentrations fell to levels below those documented at first diagnosis (Table 2).

| Parameter | First diagnosis | Intervention | Post-intervention |

| ALT, U/L | 109.0 ± 64.3 | 169.0 ± 87.4 | 118.5 ± 154.9 |

| AST, U/L | 72.7 ± 50.0 | 108.7 ± 41.9 | 66.7 ± 50.0 |

| GGT, U/L | 301.3 ± 237.3 | 393.3 ± 242.3 | 227.3 ± 117.7 |

| AP, U/L | 272.3 ± 134.8 | 300.3 ± 75.5 | 246.5 ± 95.5 |

| Bilirubin, mmol/L | 101.3 ± 164.8 | 147.1 ± 154.2 | 83.6 ± 89.8 |

There was a statistically significant difference in biochemical hepatic function parameters between the group of patients with hepatobiliary complications and subsequent intervention and those who did not experience complications (P < 0.05). The same parameters were significantly higher in patients with hepatobiliary complication compared to the group of patients who had not undergone intervention (Table 3).

| Parameter | Hepatobiliary complications | P value | |

| No (n = 148) | Yes (n = 24) | ||

| ALT, U/L | 43.2 ± 73.6 | 59.8 ± 48.7 | 0.0035 |

| AST, U/L | 29.3 ± 35.4 | 41.4 ± 35.5 | 0.0431 |

| GGT, U/L | 94.4 ± 133.2 | 186.4 ± 194.1 | 0.0005 |

| AP, U/L | 123.8 ± 88.6 | 200.3 ± 125.5 | 0.0016 |

| Bilirubin, mmol/L | 9.8 ± 6.2 | 36.5 ± 86.7 | 0.0148 |

Six patients (17.1%) experienced complications during the first intervention (Table 4). Complications occurred in three patients undergoing ERCP and stent placement (8.6%), in two patients undergoing only ERCP (5.7%), and in one patient with PTCD (2.9%). Within the first week after the intervention, an additional 34.4% of patients (n = 12) experienced complications.

| Complication | Frequency |

| During first intervention | |

| Failure visualize bile ducts | 66.7% |

| Bleeding at the papilla of vater | 16.7% |

| Bile leakage | 16.7% |

| Within first week after intervention1 | |

| Pancreatitis | 41.7% |

| Cholangitis | 33.3% |

| Hemorrhage | 8.3% |

| Wound infection | 8.3% |

| Fistula formation | 8.3% |

| Bacteremia | 8.3% |

| Abdominal pain | 8.3% |

| Abscess information | 8.3% |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 8.3% |

Antibiotic treatment was administered in ten patients following intervention, with metronidazole and amoxicillin being the two more frequently administered agents (in two patients each).

During follow-up through December 2012, a total of 11 (31.4%) patients died, whereas 23 (65.7%) patients remained alive (Figure 2). The average age at time of death was 75.6 years (range: 18-91 years), whereas the average time from onset of hepatobiliary complications to death was 7.2 years (range: 4 d to 15 years). The average age at the conclusion of the follow-up period of the 23 patients who remained alive was 55.4 years (range: 26-86 years), whereas the average time from onset of hepatobiliary complications to conclusion of follow-up was 9.2 years (range: 3 mo to 34 years). For the entire collective of patients (living and deceased), the average period following onset of hepatobiliary complications was 8.8 years.

To date, only a few studies have investigated the biliary complications of AE. In addition to rare vascular, cerebral, and musculoskeletal complications, AE is associated with hepatobiliary complications, for which the incidence and treatment have been reported in only a few studies with small numbers of patients[13-16,21] and case reports[17-20]. Vascular complications include the Budd-Chiari[25,26] and Vena-cava syndrome[27,28], which are caused by occlusions of the hepatic veins[25] or inferior vena cava[27], respectively. Cerebral involvement is associated with immunosuppression and occurs in 1%-5% of cases[29,30], whereas musculoskeletal manifestation resembles a type of spondylitis when the spinal column is impacted, or an abscess in soft tissue[31,32]. Hepatobiliary complications manifest as cholestatic jaundice, cholangitis, biliary colic, and fever[1,5]. The rate of biliary invasion is given at 11.4%[16]. In our overall collective, hepatobiliary complications occurred in 35 of a total 357 patients. The resulting complication rate of 9.8% is comparable to findings published by Ozturk et al[16]. A recent study by Frei et al[21] reports a complication rate of 30% in patients with non-resectable AE. In the present study, 24/322 patients with non-resectable AE experienced hepatobiliary complications, corresponding to a rate of 10.7%.

The main symptoms reported by patients in our collective included jaundice, abdominal complaints, and weight loss, which correspond to symptoms reported in other studies[13]. Similarly, the predominant indications of intervention in our study were obstructive jaundice and cholangitis, which agrees with the results of other studies[16,17]. Other indications for intervention reported in the literature, such as biliary fistulae[16], portal vein thrombosis, and esophageal varices[22], were not observed in our collective. On average, hepatobiliary complications occurred 3.7 years following first diagnosis. This was more rapid than the average of 15 years reported in the recent study by Frei et al[21].

Other data show that only in a few cases (n = 5) did a single interventional procedure suffice in the treatment hepatobiliary complications of AE. This corresponds to experience with other disorders, such as chronic pancreatitis or benign stenosis of the bile duct secondary to iatrogenic injury, in which, on average, two to eight ERCPs are required[32]. With malignant bile duct stenosis, the literature reports not only multiple interventions but, in many cases, also simultaneous double stenting[33,34]. Despite frequent repetition, however, the complication rates associated with interventional procedures is low, reported at 9.8% for ERCP[35] and 7.9% for PTCD[36]. MRCP is generally accomplished without complication[37]. Our rate of complications is comparable to, or lower than, corresponding reports in the literature. Only the subgroup of ten patients in whom symptoms did resolve within one week showed an elevated complication rate of 28.6%; this is most likely due to the complex nature of the clinical situation and the need for stent placement[35]. In order to avoid complications secondary to stent occlusion, stents should be regularly exchanged[32].

As a result of intervention, six patients exhibited improvement in biochemical hepatic function parameters, with concentrations falling to levels lower than those measured at first diagnosis. This improvement is associated with patients’ improved clinical conditions[13,16], which is reflected in our study by the fact that, following intervention, only two patients required additional surgery. In our collective, we were not able to identify any difference in the rate of surgery between patients with and without hepatobiliary complications. Our data also confirm that prior liver resection does not represent a risk factor for the development of hepatobiliary complications[21].

To date, only one study by Frei et al[21] has investigated survival following onset of hepatobiliary complications. They report a survival of only three years following onset of complications, which, in their series, occurred in about 30% of patients. By contrast, data in the present study show an average survival of 8.8 years following onset of complications. On average, Frei et al[21] also report the onset of hepatobiliary complications 15.0 years following first diagnosis of AE compared with the average of 3.7 years in the present study.

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design. As a result, it was not possible to retrieve more detailed information about the complications occurring in these patients.

The data of the present study allow us to conclude that hepatobiliary complications requiring treatment occur in about 10% of patients with AE. Significant increases in biochemical hepatic function parameters are already present at the time of first diagnosis. On average, hepatobiliary complications occurred 3.7 years following first diagnosis of AE, but this time to occurrence is subject to high variability (0-41 years). Despite the fact that many patients will require multiple treatments, endoscopic interventional methods offer a well-established treatment procedure with a tolerable rate of complications and treatment-associated mortality and an average survival of 8.8 years.

Despite abundant clinical resources and technical advances, the diagnosis of alveolar echinococcosis in infected individuals, especially among inexperienced clinicians, remains challenging. With delayed diagnosis, therapy often begins in a late stage of the disease, which significantly limits treatment options.

The liver is the first organ to be affected by larval infestation. Hepatic lesions are localized to the right hepatic lobe in seven of ten cases, whereas in 40%, the liver hilus is additionally affected. Only in two of ten cases are both hepatic lobes infested.

Hepatobiliary complications occur in about 10% of patients. A significant increase in hepatic transaminase concentrations facilitates the diagnosis. Interventional methods represent viable management options.

Many patients will require multiple treatments, and endoscopic interventional methods offer a well-established treatment procedure with a tolerable rate of complications and treatment-associated mortality and an average survival of 8.8 years.

In this paper, the authors systemically described their own long-term clinical data on alveolar echinococcosis. How to effectively manage post-operative complications was still a challenging problem for the surgeons. This paper was well organized and informative.

P- Reviewer: Atanasov G, Bottcher D, Hatipoglu S, Jovanovic P, Wen H S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1121] [Cited by in RCA: 1187] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Miguet JP, Bresson-Hadni S. Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver. J Hepatol. 1989;8:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nunnari G, Pinzone MR, Gruttadauria S, Celesia BM, Madeddu G, Malaguarnera G, Pavone P, Cappellani A, Cacopardo B. Hepatic echinococcosis: clinical and therapeutic aspects. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1448-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 241] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Romig T. Epidemiology of echinococcosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2003;388:209-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ammann RW, Eckert J. Cestodes. Echinococcus. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1996;25:655-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 318] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Atanasov G, Benckert C, Thelen A, Tappe D, Frosch M, Teichmann D, Barth TF, Wittekind C, Schubert S, Jonas S. Alveolar echinococcosis-spreading disease challenging clinicians: a case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4257-4261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Davidson RK, Romig T, Jenkins E, Tryland M, Robertson LJ. The impact of globalisation on the distribution of Echinococcus multilocularis. Trends Parasitol. 2012;28:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schweiger A, Ammann RW, Candinas D, Clavien PA, Eckert J, Gottstein B, Halkic N, Muellhaupt B, Prinz BM, Reichen J. Human alveolar echinococcosis after fox population increase, Switzerland. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:878-882. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Heyd B, Weise L, Bettschart V, Gillet M. [Surgical treatment of hepatic alveolar echinococcosis]. Chirurg. 2000;71:16-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Craig P. Echinococcus multilocularis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2003;16:437-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Buttenschoen K, Carli Buttenschoen D, Gruener B, Kern P, Beger HG, Henne-Bruns D, Reuter S. Long-term experience on surgical treatment of alveolar echinococcosis. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2009;394:689-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kern P, Kratzer W, Reuter S. Alveolar echinococcosis: diagnosis. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2000;125:59-62. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sezgin O, Altintaş E, Saritaş U, Sahin B. Hepatic alveolar echinococcosis: clinical and radiologic features and endoscopic management. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:160-167. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Erzurumlu K, Dervisoglu A, Polat C, Senyurek G, Yetim I, Hokelek M. Intrabiliary rupture: an algorithm in the treatment of controversial complication of hepatic hydatidosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2472-2476. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sharma BC, Reddy RS, Garg V. Endoscopic management of hepatic hydatid cyst with biliary communication. Dig Endosc. 2012;24:267-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ozturk G, Polat KY, Yildirgan MI, Aydinli B, Atamanalp SS, Aydin U. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24:1365-1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hilmioglu F, Dalay R, Caner ME, Boyacioglu S, Cumhur T, Sahin B. ERCP findings in hepatic alveolar echinococcosis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37:470-473. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gschwantler M, Brownstone E, Erben WD, Auer H, Weiss W. Combined endoscopic and pharmaceutical treatment of alveolar echinococcosis with rupture into the biliary tree. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:238-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Koroglu M, Akhan O, Gelen MT, Koroglu BK, Yildiz H, Kerman G, Oyar O. Complete resolution of an alveolar echinococcosis liver lesion following percutaneous treatment. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rosenfeld GA, Nimmo M, Hague C, Buczkowski A, Yoshida EM. Echinococcus presenting as painless jaundice. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26:684-685. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Frei P, Misselwitz B, Prakash MK, Schoepfer AM, Prinz Vavricka BM, Müllhaupt B, Fried M, Lehmann K, Ammann RW, Vavricka SR. Late biliary complications in human alveolar echinococcosis are associated with high mortality. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:5881-5888. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kern P. Clinical features and treatment of alveolar echinococcosis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:505-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1333] [Article Influence: 88.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Çakmak E, Alagozlu H, Gumus C, Alí C. A case of Budd-Chiari syndrome associated with alveolar echinococcosis. Korean J Parasitol. 2013;51:475-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Vogel J, Görich J, Kramme E, Merkle E, Sokiranski R, Kern P, Brambs HJ. Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver: percutaneous stent therapy in Budd-Chiari syndrome. Gut. 1996;39:762-764. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Fleiner-Hoffmann AF, Pfammatter T, Leu AJ, Ammann RW, Hoffmann U. Alveolar echinococcosis of the liver: sequelae of chronic inferior vena cava obstructions in the hepatic segment. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2503-2508. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Rossi IA, Delay D, Qanadli SD, Jaussi A. Inferior vena cava syndrome due to Echinococcus multilocularis. Echocardiography. 2009;26:842-846. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ozdemir NG, Kurt A, Binici DN, Ozsoy KM. Echinococcus alveolaris: presenting as a cerebral metastasis. Turk Neurosurg. 2012;22:448-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tüzün M, Hekimoğlu B. Pictorial essay. Various locations of cystic and alveolar hydatid disease: CT appearances. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:81-87. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Kern P, Bardonnet K, Renner E, Auer H, Pawlowski Z, Ammann RW, Vuitton DA, Kern P. European echinococcosis registry: human alveolar echinococcosis, Europe, 1982-2000. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:343-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lawrence C, Romagnuolo J, Payne KM, Hawes RH, Cotton PB. Low symptomatic premature stent occlusion of multiple plastic stents for benign biliary strictures: comparing standard and prolonged stent change intervals. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:558-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Tonozuka R, Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F, Moriyasu F. Endoscopic double stenting for the treatment of malignant biliary and duodenal obstruction due to pancreatic cancer. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 2:100-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Maetani I, Ogawa S, Hoshi H, Sato M, Yoshioka H, Igarashi Y, Sakai Y. Self-expanding metal stents for palliative treatment of malignant biliary and duodenal stenoses. Endoscopy. 1994;26:701-704. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Szary NM, Al-Kawas FH. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: how to avoid and manage them. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2013;9:496-504. [PubMed] |

| 35. | de Jong EA, Moelker A, Leertouwer T, Spronk S, Van Dijk M, van Eijck CH. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with postsurgical bile leakage and nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Dig Surg. 2013;30:444-450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hossary SH, Zytoon AA, Eid M, Hamed A, Sharaan M, Ebrahim AA. MR cholangiopancreatography of the pancreas and biliary system: a review of the current applications. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2014;43:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Draganov P, Hoffman B, Marsh W, Cotton P, Cunningham J. Long-term outcome in patients with benign biliary strictures treated endoscopically with multiple stents. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:680-686. [PubMed] |