Published online Apr 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4919

Peer-review started: October 27, 2014

First decision: November 14, 2014

Revised: December 2, 2014

Accepted: February 12, 2015

Article in press: February 13, 2015

Published online: April 28, 2015

Processing time: 188 Days and 1.6 Hours

AIM: To investigate the preventive effects of low-dose proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) in end-stage renal disease.

METHODS: This was a retrospective cohort study that reviewed 544 patients with end-stage renal disease who started dialysis at our center between 2005 and 2013. We examined the incidence of UGIB in 175 patients treated with low-dose PPIs and 369 patients not treated with PPIs (control group).

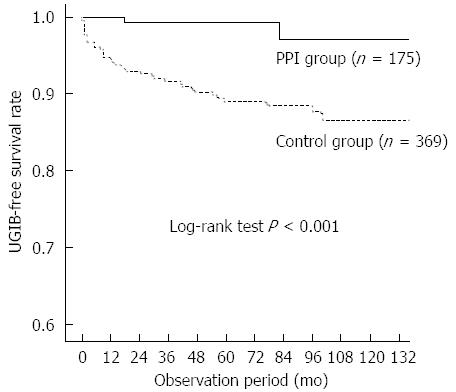

RESULTS: During the study period, 41 patients developed UGIB, a rate of 14.4/1000 person-years. The mean time between the start of dialysis and UGIB events was 26.3 ± 29.6 mo. Bleeding occurred in only two patients in the PPI group (2.5/1000 person-years) and in 39 patients in the control group (19.2/1000 person-years). Kaplan-Meier analysis of cumulative non-bleeding survival showed that the probability of UGIB was significantly lower in the PPI group than in the control group (log-rank test, P < 0.001). Univariate analysis showed that coronary artery disease, PPI use, anti-coagulation, and anti-platelet therapy were associated with UGIB. After adjustments for the potential factors influencing risk of UGIB, PPI use was shown to be significantly beneficial in reducing UGIB compared to the control group (HR = 13.7, 95%CI: 1.8-101.6; P = 0.011).

CONCLUSION: The use of low-dose PPIs in patients with end-stage renal disease is associated with a low frequency of UGIB.

Core tip: Patients with end-stage renal disease are at a high risk for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB). The aim of this study was to assess the effects of low-dose proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) for the prevention of UGIB in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal disease who began dialysis at our center between 2005 and 2013. The cumulative non-bleeding survival showed that the probability of UGIB was significantly lower in the PPI group than in the controls. PPI use was beneficial in reducing UGIB compared to the control (HR = 13.7, 95%CI: 1.8-101.6; P = 0.011).

- Citation: Song YR, Kim HJ, Kim JK, Kim SG, Kim SE. Proton-pump inhibitors for prevention of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients undergoing dialysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(16): 4919-4924

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i16/4919.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i16.4919

Patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at high risk for bleeding complications[1-4]. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) occurs most frequently in patients undergoing dialysis and is associated with higher re-bleeding risk and mortality than the general population[5-7]. Neither the origin nor pathogenesis of UGIB has been elucidated, although platelet dysfunction, blood coagulation abnormalities, and anemia may contribute to bleeding tendency[8,9]. Patients undergoing hemodialysis (HD) have increased risk for UGIB due to repeated anti-coagulant exposure compared with peritoneal dialysis (PD) patients[10]. In the general population, the incidence of UGIB has been declining over time; however, UGIB among patients with ESRD has not decreased in the past ten years according to data from the United States Renal Data System[11]. It was estimated that UGIB accounts for 3%-7% of all deaths among patients with ESRD[4], and prevention of UGIB remains a challenge for the nephrologist. There are multiple strategies to reduce UGIB, and proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of UGIB and are advocated for patients at high risk for UGIB who are taking aspirin, dual anti-platelet therapy, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)[12,13].

Patients with ESRD have a high prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms with increased use of acid suppressive therapy[14]. According to the 2011 annual report from the Korean registry system, the frequencies of gastrointestinal disease in patients undergoing HD and PD were 10.1% and 9.3%, respectively[15]. Long-term acid suppression with PPIs rarely produces adverse events and PPIs are considered safe in patients with ESRD. When medical insurance coverage of low-dose PPI was instituted in Korea, prescriptions for low-dose PPI increased in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. We found that about 30% of patients with ESRD who started dialysis at our center were prescribed PPI at discharge between 2010 and 2012. In the present study, we retrospectively investigated the protective effect of low-dose PPIs on UGIB in a cohort of patients with ESRD.

The present study was based on a retrospective review of the clinical records of patients with ESRD who began dialysis between January 2005 and May 2013 at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Anyang, Korea. Patients were excluded if: they had a previous peptic (gastric and/or duodenal) ulcer; were younger than 18 years of age; had a history of gastric surgery, malignancy, or liver cirrhosis; had undergone dialysis for < 3 mo; had a total follow-up duration of < 6 mo; received renal transplantation; or were prescribed a histamine H2-receptor antagonist, corticosteroid, or NSAID. We divided the patients into the those receiving PPIs and those not treated with PPIs (control group). This study was approved by the Investigation and Ethics Committee for Human Research at the Hallym Sacred Heart Hospital, in accordance with the principles of good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki.

UGIB was defined as a diagnosis made by the gastroenterologist in combination with no other defined bleeding cause. A gastroenterologist performed an endoscopy if a patient with ESRD showed a clinical suspicion of bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or unexplained hemoglobin decrease of > 2 g/dL. An endoscopic finding of high-risk stigmata, including active bleeding, visible vessel, or adherent clot, and blood in the stomach was defined as bleeding. Patients bleeding from esophageal and/or gastric varices were excluded from the study. Peptic ulcer bleeding was classified as gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, or both. Re-bleeding was defined as a repeat endoscopy for a clinical suspicion of re-bleeding and a finding of high-risk stigmata and blood in the stomach.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). All data are expressed as mean ± SD or median with ranges. Continuous data were analyzed by Student’s t test for equal variance or Mann-Whitney U test for unequal variance, and categorical valuables were investigated by Pearson’s χ2 test. The cumulative non-bleeding rates in the two groups were estimated using Kaplan-Meier survival estimates and the log-rank test was used to determine the differences between the curves. Multivariate Cox’s proportional hazard model analysis was used to evaluate the independent predictors for UGIB. Differences with P < 0.05 were accepted as statistically significant.

We retrospectively reviewed 544 patients with ESRD who began dialysis at Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital between January 2005 and March 2013. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort are as follows: mean age, 63.1 ± 14.0 years; male, 54.0% (n = 299); patients undergoing HD, 87.7% (n = 486); diabetes, 52.9% (n = 293); smoking, 2.7% (n = 15). Ninety-six patients had a history of coronary artery disease, 17 patients were treated with warfarin, 257 patients received aspirin, and 42 patients received dual anti-platelet therapy. Among the 544 patients, there were 175 in the PPI group (152 patients received pantoprazole 20 mg orally once a day and 23 received rabeprazole 10 mg orally once a day) and 369 in the control group. The baseline characteristics of the groups are summarized in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, sex, primary renal disease, mode of dialysis, smoking, warfarin use, anti-platelet use, body mass index, or biochemical parameters between the two groups.

| Characteristic | PPI group(n = 175) | Control group(n = 369) |

| Age, yr | 63.9 ± 12.8 | 62.7 ± 14.5 |

| Follow-up (mo) | 55.7 ± 33.6a | 66.5 ± 37.5 |

| Sex, male | 98 (57.1) | 201 (54.5) |

| Hypertension | 99 (56.6) | 215 (58.3) |

| Diabetes | 90 (51.4) | 203 (55.0) |

| Smoking | 11 (40.7) | 4 (12.1) |

| Hemodialysis | 153 (87.4) | 333 (90.24) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 23.4 ± 3.2 | 23.5 ± 3.9 |

| Previous cardiovascular disease | ||

| Cerebrovascular accident | 18 (10.3) | 49 (13.3) |

| Coronary heart disease | 28 (16.0) | 68 (18.4) |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 (1.1) | 3 (0.8) |

| Aspirin use | 82 (46.9) | 175 (47.4) |

| Dual anti-platelet therapy | 15 (8.6) | 32 (8.7) |

| Warfarin | 9 (5.1) | 8 (2.2) |

| Helicobacter pyroli | ||

| Positive | 36 (6.0) | 53 (15.0) |

| No test | 139 (79.4) | 316 (85.6) |

| Baseline laboratory findings | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 9.1 ± 1.6 | 8.8 ± 1.6 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 27.3 ± 5.3 | 26.2 ± 5.1 |

| Creatinine (mmol/L) | 6.7 ± 2.9 | 7.2 ± 3.2 |

| Protein (g/L) | 7.3 ± 0.9 | 7.2 ± 0.9 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.6 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 11.0 ± 18.8 | 9.6 ± 17.2 |

| Death | 7 (4.0) | 18 (4.9) |

During the study period, 41 patients developed UGIB, a rate of 14.4 /1000 person-years, and the incidence of UGIB was 20.7/1000 person-years in patients receiving warfarin or anti-platelet therapy. The mean time between the initiation of dialysis and UGIB events was 26.3 ± 29.6 mo. Table 2 shows the sources of UGIB. Gastric lesions were the most common cause of UGIB in patients with ESRD, accounting for 50% of bleeding sources. Eighteen patients presented with melena or hematochezia, 13 patients were admitted with hematemesis, and 10 underwent endoscopy due to unexplained anemia. The hemoglobin level at admission was 6.6 ± 1.8 g/dL and 40 patients received a red blood cell transfusion, with a median of 4.0 units (range: 1-15 units) and average of 4.5 units. Two patients experienced re-bleeding, one in the control group and the other in the PPI group, and there was one death related to UGIB in the control group.

| Cause | Patients (n) |

| Gastric ulcer | 19 |

| Duodenal ulcer | 7 |

| Duodenal and gastric ulcer | 1 |

| Dieulafoy’s lesion | 7 |

| Mallory-Weiss tear | 2 |

| Gastric erosion | 2 |

| Duodenal erosion | 2 |

| Gastric cancer | 1 |

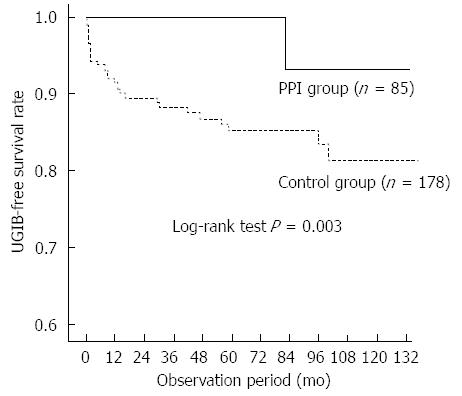

There were no significant differences in age, sex, primary renal disease, diabetes, body mass index, or biochemical parameters between patients with and without UGIB. Patients with UGIB had significantly higher frequency of warfarin use (P = 0.017) and anti-platelet therapy (P = 0.041) than those without UGIB. Bleeding occurred in only two patients (2.5/1000 person-years) in the PPI group and 39 patients (19.2/1000 person-years) in the control group. Kaplan-Meier analysis of cumulative non-bleeding survival showed that the probability of UGIB was significantly lower in the PPI group than in the control group (log rank test, P < 0.001; Figure 1). In the subgroup analysis of patients treated with warfarin or anti-platelet therapy, PPI use significantly decreased the risk for UGIB (log rank test, P = 0.003; Figure 2).

Univariate analysis showed that coronary artery disease, no use of PPIs, warfarin, and anti-platelet therapy were associated with UGIB. After adjustments for age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, smoking, coronary heart disease, hemoglobin, albumin, and mode of dialysis, PPI use was significantly beneficial in reducing UGIB compared to the control (HR = 13.7, 95%CI: 1.8-101.6, P = 0.011; Table 3).

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| PPI (no treatment vs treatment) | 13.689 | 1.84-101.64 | 0.011 |

| Warfarin | 4.728 | 1.57-14.25 | 0.006 |

| Anti-platelet therapy | 2.476 | 1.38-4.44 | 0.002 |

| Coronary artery disease | 2.079 | 0.954-4.532 | 0.094 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1.492 | 0.973-2.287 | 0.067 |

| Smoking | 2.154 | 0.659-7.043 | 0.204 |

| Diabetes | 1.020 | 0.48-2.30 | 0.899 |

| Hypertension | 1.318 | 0.59-2.92 | 0.497 |

| Age | 1.002 | 0.97-1.03 | 0.870 |

In the present study, we found that the incidence of UGIB in patients with ESRD was relatively high, and the use of PPIs was associated with a significant reduction in UGIB events. In our cohort, the incidence of UGIB in patients with ESRD was 14.4/1000 person-years and the mean time from initiation of dialysis to UGIB was 26.3 ± 29.6 mo. The incidence of UGIB was significantly lower in the PPI group than in the control group, and these preventive effects were maintained in patients receiving anti-platelet or warfarin therapy. These results suggest that UGIB may be prevented by PPIs in patients with ESRD.

The risk of UGIB in dialysis patients is thought to be higher than in the general population. In the United States Renal Data System Dialysis Morbidity and Mortality Study, the incidence of UGIB in patients with ESRD was 22.8/1000 person-years[3], similar to the incidence in the control group and higher than that in the PPI group. The incidence of UGIB in HD patients was 42.0/1000 person-years according to data from Taiwan National Health Insurance Research Database[5], which is higher than the incidence in our study. These results may be related to inclusion of PD patients and exclusion of patients with liver cirrhosis and patients receiving NSAIDs or steroids. In the present study, the two- and four-year cumulative incidences of UGIB in the control group were 8.2% and 13.1%, respectively. Although the risk factors related with UGIB in patients with ESRD are uncertain, we found that warfarin therapy and use of anti-platelet agents are significantly associated. Wassel et al[3] reported that smoking, history of cardiovascular disease, and inability to ambulate were associated with a higher risk of UGIB. In data from Taiwan HD patients, diabetes, cirrhosis, coronary artery disease, and use of NSAIDs were significant risk factors for UGIB[16]. Chen et al[17] found that diabetes, congestive heart failure, albumin, and PD were risk factors for peptic ulcers in patients with ESRD. In the present study, we did not include data regarding ambulatory status and excluded patients with liver cirrhosis and those receiving NSAIDs.

We investigated the efficacy of PPIs in the prevention of UGIB in patients with ESRD. In the Korean National Health Insurance program, low-dose PPIs are covered for prophylaxis against ulcers or to relieve gastric or reflux symptoms. Due to the retrospective observational nature of the present study, patients were not randomly assigned to the PPI or control group. Most of the patients in the PPI group had gastric or reflux symptoms and there were no significant differences in age, sex, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, or smoking between the two groups. Nonetheless, we found a significant preventive effect of PPIs on UGIB in patients with ESRD. PPIs are frequently used to prevent UGIB in patients receiving dual anti-platelet therapy. Liang et al[18] reported that prophylactic use of omeprazole was effective in lowering the incidence of peptic ulcer disease in HD patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report to suggest the preventive efficacy of PPI for UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis. Because several studies have suggested relationships among impaired bone metabolism[19], fractures[20], vascular calcification[21], and PPIs, we evaluated mortality in the two groups. There was no significant difference in mortality according to the use of PPIs. However, we did not assess vascular calcification and bone mineral density.

This study had several limitations. First, as this was not a randomized controlled trial, we can not draw general conclusions. However, in practice, it is difficult to perform a randomized controlled trial due to ethical problems. Second, we examined Helicobacter pylori in only a small portion of patients. Third, we excluded patients receiving H2 receptor antagonists. It has been suggested that H2 receptor antagonists can be used as alternatives to PPIs to prevent UGIB during dual anti-platelet therapy without an increase in the risk of cardiovascular outcomes. Finally, we did not assess long-term adverse effects of PPIs in patients with ESRD because we did not assess vascular calcification, serum magnesium, mineral bone disease states, or bone fractures.

In conclusion, we found that the risk of UGIB in patients with ESRD was lower in the PPI group than the control group. In addition, PPI did not increase mortality and may be safe and effective for prevention of UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis. Future large-scale controlled trials are necessary to confirm our results.

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) occurs most frequently in patients undergoing dialysis and is associated with higher re-bleeding risk and mortality in these patients than in the general population. It was estimated that UGIB accounts for 3%-7% of all deaths among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and prevention of UGIB remains a challenge for the nephrologist. Proton-pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been demonstrated to reduce the risk of UGIB and are advocated for patients at high risk for UGIB who are taking aspirin, dual anti-platelet therapy and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Recently, a number of practice guidelines recommend administering prophylactic PPI to patients who are at high risk of UGIB. However, there exist limited data regarding the efficacy of PPIs for the prevention of UGIB, and there are no formal guidelines about the use of a PPI for gastroprotection in patients with ESRD. The current research investigated whether PPIs are effective in reducing UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis.

This study revealed a significant preventive effect of PPIs on UGIB in patients with ESRD. PPIs are frequently used to prevent UGIB in patients receiving dual anti-platelet therapy. One study reported that prophylactic use of omeprazole was effective in lowering the incidence of peptic ulcer disease in hemodialysis patients. To our knowledge, this is the first report to suggest the preventive efficacy of PPI for UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis.

The study results show that the risk of UGIB in patients with ESRD is lower in the PPI group than the control group. In addition, PPI did not increase the mortality and may be safe and effective for prevention of UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis.

UGIB is diagnosed by performing an endoscopy if a patient with ESRD shows a clinical suspicion of bleeding, such as hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, or unexplained hemoglobin decrease of > 2 g/dL. In this study, bleeding was used to describe an endoscopic finding of high-risk stigmata, including active bleeding, visible vessel, or adherent clot, and blood in the stomach.

This is an interesting study in which the authors investigated the preventive effect of PPI on UGIB in patients with ESRD, especially patients undergoing dialysis. The results are interesting and suggest that PPI could be used for preventing UGIB in patients undergoing dialysis.

P- Reviewer: Dina I, Inamori M, Luo JC, Stanciu C, Weber FH S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: AmEditor E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Gheissari A, Rajyaguru V, Kumashiro R, Matsumoto T. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage in end stage renal disease patients. Int Surg. 1990;75:93-95. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Alvarez L, Puleo J, Balint JA. Investigation of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with end stage renal disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88:30-33. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Wassel H, Gillen DL, Ball AM, Kestenbaum BR, Seliger SL, Sherrard D, Stehman-Breen CO. Risk factors for upper gastrointestinal bleeding among end-stage renal disease patients. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1455-1461. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Boyle JM, Johnston B. Acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in patients with chronic renal disease. Am J Med. 1983;75:409-412. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kuo CC, Kuo HW, Lee IM, Lee CT, Yang CY. The risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with hemodialysis: a population-based cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Luo JC, Leu HB, Hou MC, Huang KW, Lin HC, Lee FY, Chan WL, Lin SJ, Chen JW. Nonpeptic ulcer, nonvariceal gastrointestinal bleeding in hemodialysis patients. Am J Med. 2013;126:264.e25-264.e32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sugimoto M, Sakai K, Kita M, Imanishi J, Yamaoka Y. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in long-term hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2009;75:96-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wu CY, Wu CH, Wu MS, Wang CB, Cheng JS, Kuo KN, Lin JT. A nationwide population-based cohort study shows reduced hospitalization for peptic ulcer disease associated with H pylori eradication and proton pump inhibitor use. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:427-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kaw D, Malhotra D. Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19:317-322. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Johnsen SP, Sørensen HT, Mellemkjoer L, Blot WJ, Nielsen GL, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH. Hospitalisation for upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with use of oral anticoagulants. Thromb Haemost. 2001;86:563-568. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Yang JY, Lee TC, Montez-Rath ME, Paik J, Chertow GM, Desai M, Winkelmayer WC. Trends in acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;23:495-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hsiao FY, Tsai YW, Huang WF, Wen YW, Chen PF, Chang PY, Kuo KN. A comparison of aspirin and clopidogrel with or without proton pump inhibitors for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular events in patients at high risk for gastrointestinal bleeding. Clin Ther. 2009;31:2038-2047. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lanas A, Rodrigo L, Márquez JL, Bajador E, Pérez-Roldan F, Cabrol J, Quintero E, Montoro M, Gomollón F, Santolaria S. Low frequency of upper gastrointestinal complications in a cohort of high-risk patients taking low-dose aspirin or NSAIDS and omeprazole. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:693-700. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cano AE, Neil AK, Kang JY, Barnabas A, Eastwood JB, Nelson SR, Hartley I, Maxwell D. Gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with end-stage renal disease undergoing treatment by hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1990-1997. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Jin DC. Current status of dialysis therapy in Korea. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26:123-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Luo JC, Leu HB, Huang KW, Huang CC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Lee FY, Lee SD. Incidence of bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers in patients with end-stage renal disease receiving hemodialysis. CMAJ. 2011;183:E1345-E1351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chen YT, Yang WC, Lin CC, Ng YY, Chen JY, Li SY. Comparison of peptic ulcer disease risk between peritoneal and hemodialysis patients. Am J Nephrol. 2010;32:212-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liang CC, Wang IK, Lin HH, Yeh HC, Liu JH, Kuo HL, Hsu WM, Huang CC, Chang CT. Prophylactic use of omeprazole associated with a reduced risk of peptic ulcer disease among maintenance hemodialysis patients. Ren Fail. 2011;33:323-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kirkpantur A, Altun B, Arici M, Turgan C. Proton pump inhibitor omeprazole use is associated with low bone mineral density in maintenance haemodialysis patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yu EW, Bauer SR, Bain PA, Bauer DC. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: a meta-analysis of 11 international studies. Am J Med. 2011;124:519-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 214] [Article Influence: 15.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Fusaro M, Noale M, Tripepi G, Giannini S, D’Angelo A, Pica A, Calò LA, Miozzo D, Gallieni M. Long-term proton pump inhibitor use is associated with vascular calcification in chronic kidney disease: a cross-sectional study using propensity score analysis. Drug Saf. 2013;36:635-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |