Published online Apr 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4707

Peer-review started: September 29, 2014

First decision: November 17, 2014

Revised: December 2, 2014

Accepted: December 19, 2014

Article in press: December 22, 2014

Published online: April 21, 2015

Processing time: 205 Days and 22.2 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the effect of a relaxing visual distraction alone on patient pain, anxiety, and satisfaction during colonoscopy.

METHODS: This study was designed as an endoscopist-blinded randomized controlled trial with 60 consecutively enrolled patients who underwent elective colonoscopy at Yokohama City University Hospital, Japan. Patients were randomly assigned to two groups: group 1 watched a silent movie using a head-mounted display, while group 2 only wore the display. All of the colonoscopies were performed without sedation. We examined pain, anxiety, and the satisfaction of patients before and after the procedure using questionnaires that included the Visual Analog Scale. Patients were also asked whether they would be willing to use the same method for a repeat procedure.

RESULTS: A total of 60 patients were allocated to two groups. Two patients assigned to group 1 and one patient assigned to group 2 were excluded after the randomization. Twenty-eight patients in group 1 and 29 patients in group 2 were entered into the final analysis. The groups were similar in terms of gender, age, history of prior colonoscopy, and pre-procedural anxiety score. The two groups were comparable in terms of the cecal insertion rate, the time to reach the cecum, the time needed for the total procedure, and vital signs. The median anxiety score during the colonoscopy did not differ significantly between the two groups (median scores, 20 vs 24). The median pain score during the procedure was lower in group 1, but the difference was not significant (median scores, 24.5 vs 42). The patients in group 1 reported significantly higher median post-procedural satisfaction levels, compared with the patients in group 2 (median scores, 89 vs 72, P = 0.04). Nearly three-quarters of the patients in group 1 wished to use the same method for repeat procedures, and the difference in rates between the two groups was statistically significant (75.0% vs 48.3%, P = 0.04). Patients with greater levels of anxiety before the procedure tended to feel a painful sensation. Among patients with a pre-procedural anxiety score of 50 or higher, the anxiety score during the procedure was significantly lower in the group that received the visual distraction (median scores, 20 vs 68, P = 0.05); the pain score during the colonoscopy was also lower (median scores, 23 vs 57, P = 0.04). No adverse effects arising from the visual distraction were recognized.

CONCLUSION: Visual distraction alone improves satisfaction in patients undergoing colonoscopy and decreases anxiety and pain during the procedure among patients with a high pre-procedural anxiety score.

Core tip: We conducted a randomized controlled trial to test the effect of relaxing visual distraction during colonoscopy. Sixty patients were randomly assigned to two groups: group 1 watched a silent movie using a head-mounted display, while group 2 only wore the display. Patients in group 1 reported a significantly higher post-procedural satisfaction. Among those with a high pre-procedural anxiety score, the scores for anxiety and pain during the procedure were significantly lower in the group with the visual distraction. Visual distraction alone improves satisfaction during a colonoscopy and decreases anxiety and pain among patients with a high pre-procedural anxiety score.

- Citation: Umezawa S, Higurashi T, Uchiyama S, Sakai E, Ohkubo H, Endo H, Nonaka T, Nakajima A. Visual distraction alone for the improvement of colonoscopy-related pain and satisfaction. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15): 4707-4714

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i15/4707.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4707

Colorectal cancer is one of the most commonly encountered neoplasms worldwide[1], and both its prevalence and mortality rates have been increasing[2]. Colonoscopy plays an important role in reducing colorectal cancer death not only through the diagnosis of colon cancer but also the removal of premalignant lesions and early cancers[3,4]. In addition, colonoscopy is the most reliable tool for evaluating inflammatory bowel disease and for detecting other structural lesions of the colon. Thus, colonoscopy is becoming increasingly important.

However, colonoscopy is considered to be an uncomfortable procedure and is often accompanied by pain. Anxiety regarding the procedure and fear of pain are two reasons why some patients do not undergo an endoscopy for cancer screening[5]. Thus, methods for reducing anxiety and fear are needed to enable a higher rate of screening colonoscopy.

Most centers currently use some form of sedation to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures[6,7]. However, the use of sedative drugs increases the risk of colonoscopy-related complications, including respiratory depression, hypotension, and even myocardial ischemia[8-10]. Ko et al[11] performed a study examining complications after screening or surveillance colonoscopy and reported that respiratory depression, which is the most common immediate complication, occurred in 7.5 of 1000 persons, while cardiovascular complications, including hypotension and bradycardia, occurred in 4.9 of 1000 persons. The majority of complications were self-limited, but medications including atropine, flumazenil, and naloxone were administered for rescue in some cases. In terms of expense, sedated colonoscopies were more costly, and it was reported that a cost-savings of $106 to $206 per single procedure was feasible by not using sedation[12]. Moreover, a study in France reported that sedation (usually propofol) administered by anesthesiologists, added 285% to the cost of colonoscopy (€740 vs€192 for a colonoscopy with vs without an anesthesiologist, respectively)[13].

Therefore, safe and inexpensive methods for optimizing colonoscopy performance without the use of routine sedation should be a target of further research assessment. The use of various distraction techniques, including auditory and olfactory stimulation, to decrease pain and anxiety has been reported in association with other medical procedures[14-16]. The effects of music on alleviating anxiety and decreasing the dose of sedation during endoscopy have been reported in a number of studies[17-19]. Other studies have shown that aromatherapy can be an inexpensive, safe, and effective procedural tool[20,21].

Methods using visual stimulation have also been reported to be effective in other medical procedures[22,23]. Although visual distraction is feasible as an inexpensive, noninvasive, and effective non-pharmacological method for endoscopic procedures, few studies have analyzed the effect of visual distraction on the anxiety levels of patients undergoing a colonoscopy. To our knowledge, only two studies have investigated its beneficial effect in patients undergoing a colonoscopy[24,25]. In these trials, however, the patients underwent a colonoscopy with routine sedation and the visual distraction was partly supplied concurrently with an audio intervention. No previous study has tested the effect of visual distraction alone during a colonoscopy without any sedative medication.

We conducted a randomized controlled trial examining the use of a relaxing visual distraction alone during outpatient colonoscopy without sedation to clarify whether such visual distractions can have beneficial effects on patient pain, anxiety, and satisfaction and to examine its influence on endoscopy parameters, including insertion difficulty, insertion time, and vital signs.

This study was designed as an endoscopist-blinded randomized controlled trial to be performed in 60 consecutive patients who were undergoing elective colonoscopy for screening at Yokohama City University Hospital, Japan, between April 2012 and March 2014. The inclusion criteria were (1) attending a non-sedated screening colonoscopy; and (2) an age of between 20 years and 80 years. The exclusion criteria were (1) previous abdominal surgery; (2) visual disability; (3) history of severe heart failure, renal failure, liver cirrhosis or chronic hepatic failure; (4) personal history of anxiety or psychiatric disorders; (5) chronic pain disorders; and (6) pregnancy or possibility of pregnancy.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to their participation in the study. The study protocol was approved by the Yokohama City University Hospital Ethics Committee. This trial was registered in the University Hospital Medical Information Network (UMIN) Clinical Trials Registry as UMIN 000009009.

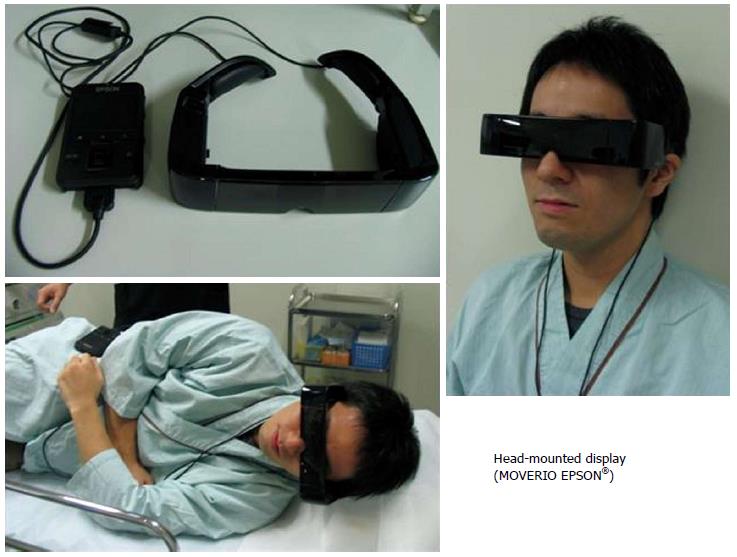

Participating patients were randomly assigned using computer generated numbers into two groups: group 1 received a visual distraction, while group 2 did not receive a relaxation method. All participants were directed not to tell anyone to which group they had been assigned. Patients in both groups wore a head-mounted display (MOVERIO EPSON®; SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION, Nagano Japan). We used a see-through display that projects images visible only from the inside without blocking the vision of the patients because a visual field loss might have increased the anxiety levels of the patients (Figure 1). To evaluate the effect of visual distraction alone, the patients in group 1 watched a silent movie (silent comedy), while those in group 2 wore the displays but did not watch a movie. The randomization procedure and the display mounting were performed by doctors who were not endoscopists. As a result, the endoscopists remained blind to whether the patients were or were not watching a movie until the examination was completed. All of the colonoscopies were performed without carbon dioxide insufflation, sedative medication, music, or any other methods that could have impacted patient anxiety or pain during the colonoscopy. In Japan, screening colonoscopy is usually carried out without sedative drugs. We were ready to provide conscious sedation as rescue measure for patients that could not tolerate pain. We also did not use antispasmodic medication, including butyl scopolamine bromide. The oxygen saturation and blood pressure were continuously monitored throughout the procedure.

We examined pain, anxiety, and the satisfaction of patients before and after an endoscopy using questionnaires that included a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) consisting of a 100-mm horizontal line that was scored from 0 to 100 for the measurement of pain, anxiety, and satisfaction; the patients were also asked whether they would be willing to use the same method for a repeat procedure. Before colonoscopy started, patients were asked severity of worry for pre-procedural anxiety score. After colonoscopy had been finished, patients were asked highest level of anxiety and pain they felt during procedure and degree of satisfaction.

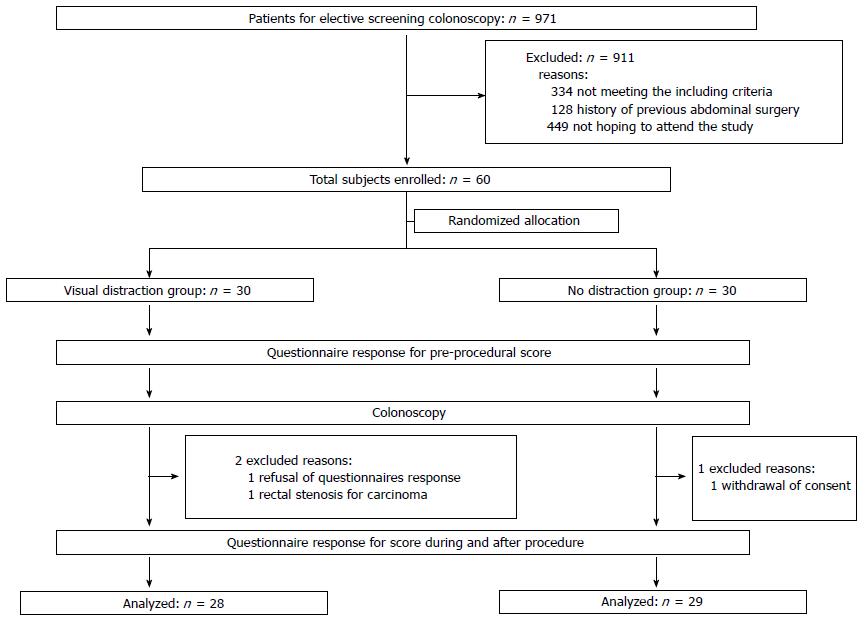

The primary outcome measures were the pain score during colonoscopy (as scored using the VAS), the anxiety score during colonoscopy (as scored using the VAS) and the satisfaction score after colonoscopy (as scored using the VAS). Other outcomes included the cecal insertion rate, the cecal insertion time, the time required for the total procedure, and the vital signs before, during, and after the colonoscopy. A flow chart of this study is shown in Figure 2.

The sample size was estimated based on a previous study for improvement of pain during colonoscopy with music. Ovayolu demonstrated the beneficial effect of music for pain and satisfaction by a study of 60 patients undergoing elective colonoscopy[18]. As this study of Ovayolu, we assumed that there would be a 40% reduction of pain score. With P value of 0.05 and a power of 80%, it was calculated that 28 patients would be needed in each group.

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21 (International Business Machines Corporation, Armonk, New York, United States). A comparison of quantitative variables (expressed as the median, range) including the scores for pain, anxiety, and satisfaction (the primary endpoints) was performed using the Mann-Whitney test. The χ2 test was used for categorical data. A P value of 0.05 or less was regarded as statistically significant.

A total of 60 patients were allocated to two groups. Two patients assigned to group 1 and one patient assigned to group 2 were excluded after the randomization: one patient in group 1 refused to complete the questionnaire, one patient in group 1 did not undergo a total colonoscopy because of rectal stenosis from a carcinoma, and one patient in group 2 withdrew consent during the colonoscopy. As a result, 28 patients in group 1 and 29 patients in group 2 were entered into the final analysis. All the colonoscopies were performed without sedation and no patient received conscious sedation as rescue for unbearable pain. No adverse effects arising from the visual distraction were recognized.

Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics and pre-procedural anxiety scores for each group. The groups were similar in terms of gender (67.9% men in group 1% vs 65.5% in group 2), age (median, 70 years vs 66 years), history of prior colonoscopy (64.3% vs 62.1%), and pre-procedural anxiety score (median, 52.5 vs 51).

| Group 1 (visual distraction) | Group 2 (no visual distraction) | P value | |

| Number of patients | 28 | 29 | |

| Gender, male:female | 19:9 | 19:10 | 0.93 |

| Age, median (IQR, range) | 65.5 (16.25, 32-79) | 66 (11, 45-77) | 0.92 |

| Previous experience with colonoscopy | |||

| yes | 64.3% | 62.1% | 0.86 |

| Number of colonoscopies, median (range, IQR) | 2 (2, 0-8) | 2 (3, 0-10) | 0.45 |

| Pre-procedural anxiety score, median (range, IQR) | 52.5 (48.75, 0-95) | 51 (55, 0-100) | 0.53 |

The features of the colonoscopy procedures and their various outcomes, including vital signs, are provided in Table 2. The two groups were comparable in terms of the cecal insertion rate (96.4% in group 1 vs 96.6% in group 2), the time to reach the cecum (median, 639 s vs 720 s), the time needed for the total procedure (median, 921 s vs 1068 s), and the vital signs.

| Group 1 (visual distraction) | Group 2 (no visual distraction) | P value | |

| Cecal insertion rate | 96.4% | 96.6% | 0.98 |

| Time to reach cecum, in seconds, median (IQR, range) | 634.5 (230, 150-1669) | 720 (430, 326-2040) | 0.52 |

| Time needed for total procedure, in seconds, median (IQR, range) | 921 (245.25, 412-1856) | 1056 (375, 558-2375) | 0.29 |

| Systolic blood pressure, in mmHg, median (IQR, range) | |||

| Before procedure | 132.5 (22.75, 102-165) | 132 (27, 98-170) | 0.96 |

| Highest during procedure | 140 (21.75, 99-220) | 134 (46, 107-193) | 0.99 |

| After procedure | 128.5 (14.5, 97-182) | 127 (25, 100-165) | 0.85 |

The results of the questionnaires are summarized in Table 3. The median anxiety score during the colonoscopy did not differ significantly between the two groups (20 in group 1 vs 24 in group 2). The median pain score during the procedure was lower in group 1, but the difference was not significant (median scores, 24.5 in group 1 vs 42 in group 2). The patients in group 1 reported significantly higher median post-procedural satisfaction levels, compared with the patients in group 2 (median scores, 89 in group 1 vs 72 in group 2, P = 0.04). Nearly three-quarters of the patients in group 1 wished to use the same method for repeat procedures, and the difference in rates between the two groups was statistically significant (75.0% in group 1 vs 48.3% in group 2, P = 0.04).

| Group 1 (visual distraction) | Group 2 (no visual distraction) | P value | |

| Pre-procedural anxiety score, median (IQR, range) | 52.5 (48.75, 0-95) | 51 (55, 0-100) | 0.53 |

| Anxiety score during procedure, median (IQR, range) | 20 (17.25, 0-85) | 24 (67, 0-96) | 0.70 |

| Pain score during procedure, median (IQR, range) | 24.5 (33.25, 0-96) | 42 (52, 0-100) | 0.47 |

| Post-procedural satisfactory score, median (IQR, range) | 89 (21.75, 18-100) | 72 (42, 1-100) | 0.04 |

| Willing to receive the same method at next time | 75.0% | 48.3% | 0.04 |

Patients with greater levels of anxiety before the procedure tended to feel a painful sensation. The questionnaire results of the patients with a pre-procedural anxiety score of 50 or higher are shown in Table 4. Among these patients, the anxiety score during the procedure was significantly lower in the group that received the visual distraction (20 in group 1 vs 68 in group 2, P = 0.05); the pain score during the colonoscopy was also lower (23 in group 1 vs 57 in group 2, P = 0.04).

| Visual distraction | No visual distraction | P value | |

| Number of patients | 17 | 16 | 0.67 |

| Cecal insertion rate | 100% | 100% | NS |

| Time to reach cecum, in seconds, median (IQR, range) | 639 (305, 260-1669) | 611 (446.25, 326-1571) | 0.80 |

| Time needed, for total procedure, in seconds, median (IQR, range) | 923 (302, 482-1856) | 1000.5 (427.5, 558-1822) | 0.93 |

| Pre-procedural anxiety score, median (IQR, range) | 75 (18, 51-95) | 69 (24.75, 51-100) | 0.44 |

| Anxiety score during procedure, median (IQR, range) | 20 (29, 7-85) | 68 (49.75, 11-91) | 0.05 |

| Pain score during procedure, median (IQR, range) | 23 (30, 0-83) | 57 (40.25, 2-100) | 0.04 |

The purpose of the present study was to determine the beneficial effect of a visual distraction during colonoscopy. The results of previous studies have suggested that using a visual stimulation has positive physiological and psychological impacts during other medical situations[22,23]. In endoscopic procedures, the use of various distraction techniques, including auditory and olfactory stimulation, to reduce anxiety and pain has been reported in several studies[17-21,24,25].

However, the effect of visual stimulation during colonoscopy is much less consistent. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to show the effectiveness of visual distraction alone in improving satisfaction during a colonoscopy without any sedative intervention or relaxation methods, including music. We also found that visual distraction may reduce pain, although the difference in the pain score was not significant when examined for all the patients included in this trial.

Lembo et al[24] investigated whether audio and visual distractions reduced discomfort during a flexible sigmoidoscopy. Thirty-seven patients were enrolled in this study and were randomized to groups receiving no intervention, audio stimulation alone, or audio and visual distraction. The results showed that patients receiving combination of audio and visual interventions had lower discomfort and anxiety levels, compared with the results for the other two groups. This observation supports the findings of the current study and suggests that visual distraction can be used to reduce displeasure during a colonoscopy. None of the groups in this previous study received visual intervention alone; thus, whether visual distraction alone had a beneficial effect could not be determined.

On the other hand, Lee et al[25] designed a trial to examine the effects of music and visual stimulation on pain, satisfaction, and the dose of sedative medication in patients undergoing an elective colonoscopy with propofol. In this study, 165 patients were randomly assigned to receive no intervention, visual distraction alone, or audio and visual distraction. They found that visual distraction alone did not decrease either the pain score or the dose of sedative medication, although both parameters decreased when an audio distraction was added. These results might have differed from the presently reported findings because the previous authors used a visual distraction concurrently with sedation, which might have reduced the effect of the relaxation method. In addition, the display that they used to provide the visual distraction was not see-through. Blocked views can affect the psychological state of patients, influencing anxiety levels. Another possible reason is ethnic differences. Campbell et al[26] examined 120 healthy young adults and demonstrated differences in pain responses between African Americans and Caucasians across multiple stimulus modalities. Some studies have also reported that ethnicity affects pain sensitivity[27]. Thus, the pain responses of the Japanese participants in the present trial might have differed from those of other ethnic groups, including the participants of the previous study.

As described in previous studies, we expect that a visual distraction would be more effective when used in combination with an audio distraction[24,25]. Moreover, visual stimulation might provide a more advantageous effect when used in combination with olfactory stimulation, which has been reported to improve anxiety levels during endoscopic procedures but requires further research[20,21].

The present study also demonstrated that a visual distraction reduced anxiety and pain levels during a colonoscopy in patients with high anxiety levels prior to the procedure, although the number of patients with high anxiety a bit small. Exactly how the visual distraction decreased the pain levels in patients with high anxiety levels remains uncertain. As the cecal insertion rates, times required for insertion and the total procedure, and the vital signs during colonoscopy were comparable between the two groups, the visual distraction might have had a psychological effect (including a reduction in anxiety), rather than a physical effect. Several studies have reported that anxiety induces hyperalgesia and that the threat of shock (without actual exposure) lowers pain thresholds in humans[28,29]. Elphick et al[30] found that high anxiety and anticipating discomfort were independently associated with discomfort during colonoscopy. These results supported our hypothesis that the visual distraction decreased pain by allaying some of the anxiety; thus, it was more effective in patients who were extremely anxious.

Colonoscopy is thought to be an uncomfortable and painful endoscopic procedure. In a previous study, a notable proportion of patients mentioned concerns and fears regarding discomfort as a reason why they did not undergo an endoscopic procedure for colorectal cancer screening[5]. In the present trial, a significantly higher proportion of patients in the visual distraction group expressed a preference to undergo the same technique if they had to undergo a repeat colonoscopy in the future. This result suggests that visual distraction can improve the tolerance and acceptability of a colonoscopy to patients. However, whether an increase in satisfaction as a result of the visual intervention could increase the proportion of patients undergoing a colonoscopy remains unclear, and needs further research, including a follow-up review, is necessary. Nonetheless, the use of a visual intervention would enable improvements in costs and risk arising from sedation in most endoscopy units.

Our study had several limitations. First, the beneficial effect of the visual interaction was relatively modest. We used only one movie for all the patients. In an effort to evaluate the simple impact of visual stimulation, a silent comedy was selected for use in this trial. It is possible that providing patients with a greater choice of movies might result in greater benefits. Secondly, masking of randomization might have been ineffective. Since the patients in group 1 were watching a comedy, it is expected that their behavior during the procedure might had unmasked the randomization. Thirdly, we recruited both patients for first colonoscopy and with experience of previous colonoscopies. This could have introduced bias. Fourthly, we did not have the data of insertion depth of scope when it reached cecum, which is also an important factor of pain. Fifth, the number of patients in this trial was somewhat small. The results in the high pre-procedure anxiety group with a P value of 0.04-0.05 may be of borderline significance. We consider that further investigation with larger sample size is needed to confirm the result of current study.

In conclusion, this prospective randomized trial demonstrated that visual distraction alone improves satisfaction in patients undergoing a colonoscopy without sedation and decreases anxiety and pain during the procedure in patients with high anxiety levels before the procedure. Using visual intervention could result in an improvement of the acceptability of colonoscopy and reductions in costs and complications arising from the use of sedative medication. We recommend using a visual distraction technique during colonoscopy, especially for patients with strong anxieties, as it is a simple, noninvasive, and low-cost method.

Colonoscopy is considered to be an uncomfortable procedure and is often accompanied by pain. Most centers currently use some form of sedation to reduce anxiety and pain in patients undergoing endoscopic procedures. However, the use of sedative drugs increases the risk of colonoscopy-related complications and is more costly.

Therefore, safe and inexpensive methods for optimizing colonoscopy performance without the use of routine sedation should be a target of further research assessment.

The use of various distraction techniques, including auditory and olfactory stimulation, to decrease pain and anxiety has been reported in association with other medical procedure. The effects of music on alleviating anxiety and decreasing the dose of sedation during endoscopy have been reported in a number of studies. Other studies have shown that aromatherapy can be an inexpensive, safe, and effective procedural tool. We conducted a randomized controlled trial examining the use of a relaxing visual distraction alone during outpatient colonoscopy without sedation to clarify whether such visual distractions can have beneficial effects on patient pain, anxiety, and satisfaction.

By clarifying the beneficial effect of visual distraction, using this method may lead to improvement of the acceptability of colonoscopy and reductions in costs and complications arising from the use of sedative medication.

Visual Analogue Scale: scale that consists of 100-mm horizontal line that was scored from 0 to 100 and is used to evaluate subjective findings including pain.

The manuscript revealed that visual distraction alone improves satisfaction in patients undergoing colonoscopy and decreases anxiety and pain during the procedure among patients with a high pre-procedural anxiety score. The work has good study design, well-performance, and constructive findings.

P- Reviewer: Luo JC, Inamori M, Zoras O S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, Forman D. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23762] [Cited by in RCA: 25541] [Article Influence: 1824.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Anderson WF, Umar A, Brawley OW. Colorectal carcinoma in black and white race. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2003;22:67-82. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O’Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3126] [Article Influence: 97.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Zauber AG, Winawer SJ, O’Brien MJ, Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, van Ballegooijen M, Hankey BF, Shi W, Bond JH, Schapiro M, Panish JF. Colonoscopic polypectomy and long-term prevention of colorectal-cancer deaths. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:687-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1952] [Cited by in RCA: 2285] [Article Influence: 175.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 5. | Petravage J, Swedberg J. Patient response to sigmoidoscopy recommendations via mailed reminders. J Fam Pract. 1988;27:387-389. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Keeffe EB, O’Connor KW. 1989 A/S/G/E survey of endoscopic sedation and monitoring practices. Gastrointest Endosc. 1990;36:S13-S18. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Froehlich F, Gonvers JJ, Fried M. Conscious sedation, clinically relevant complications and monitoring of endoscopy: results of a nationwide survey in Switzerland. Endoscopy. 1994;26:231-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bell GD. Preparation, premedication, and surveillance. Endoscopy. 2004;36:23-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Holm C, Christensen M, Rasmussen V, Schulze S, Rosenberg J. Hypoxaemia and myocardial ischaemia during colonoscopy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:769-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nelson DB, Barkun AN, Block KP, Burdick JS, Ginsberg GG, Greenwald DA, Kelsey PB, Nakao NL, Slivka A, Smith P. Propofol use during gastrointestinal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:876-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ko CW, Riffle S, Michaels L, Morris C, Holub J, Shapiro JA, Ciol MA, Kimmey MB, Seeff LC, Lieberman D. Serious complications within 30 days of screening and surveillance colonoscopy are uncommon. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:166-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cataldo PA. Colonoscopy without sedation. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:257-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hassan C, Benamouzig R, Spada C, Ponchon T, Zullo A, Saurin JC, Costamagna G. Cost effectiveness and projected national impact of colorectal cancer screening in France. Endoscopy. 2011;43:780-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hoffman HG, Patterson DR, Carrougher GJ. Use of virtual reality for adjunctive treatment of adult burn pain during physical therapy: a controlled study. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:244-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 265] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Johnson MH, Petrie SM. The effects of distraction on exercise and cold pressor tolerance for chronic low back pain sufferers. Pain. 1997;69:43-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Seyrek SK, Corah NL, Pace LF. Comparison of three distraction techniques in reducing stress in dental patients. J Am Dent Assoc. 1984;108:327-329. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lee DW, Chan KW, Poon CM, Ko CW, Chan KH, Sin KS, Sze TS, Chan AC. Relaxation music decreases the dose of patient-controlled sedation during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ovayolu N, Ucan O, Pehlivan S, Pehlivan Y, Buyukhatipoglu H, Savas MC, Gulsen MT. Listening to Turkish classical music decreases patients’ anxiety, pain, dissatisfaction and the dose of sedative and analgesic drugs during colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7532-7536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Palakanis KC, DeNobile JW, Sweeney WB, Blankenship CL. Effect of music therapy on state anxiety in patients undergoing flexible sigmoidoscopy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1994;37:478-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Hu PH, Peng YC, Lin YT, Chang CS, Ou MC. Aromatherapy for reducing colonoscopy related procedural anxiety and physiological parameters: a randomized controlled study. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:1082-1086. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Puttler K, Jaklic B, Rieg TS, Lucha PA. Reduction of conscious sedation requirements by olfactory stimulation: a prospective randomized single-blinded trial. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15:381-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bentsen B, Svensson P, Wenzel A. Evaluation of effect of 3D video glasses on perceived pain and unpleasantness induced by restorative dental treatment. Eur J Pain. 2001;5:373-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sander Wint S, Eshelman D, Steele J, Guzzetta CE. Effects of distraction using virtual reality glasses during lumbar punctures in adolescents with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:E8-E15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lembo T, Fitzgerald L, Matin K, Woo K, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Audio and visual stimulation reduces patient discomfort during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1113-1116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lee DW, Chan AC, Wong SK, Fung TM, Li AC, Chan SK, Mui LM, Ng EK, Chung SC. Can visual distraction decrease the dose of patient-controlled sedation required during colonoscopy? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2004;36:197-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Fillingim RB. Ethnic differences in responses to multiple experimental pain stimuli. Pain. 2005;113:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 204] [Cited by in RCA: 225] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Chan MY, Hamamura T, Janschewitz K. Ethnic differences in physical pain sensitivity: role of acculturation. Pain. 2013;154:119-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rhudy JL, Meagher MW. Fear and anxiety: divergent effects on human pain thresholds. Pain. 2000;84:65-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Gracely RH, McGrath P, Dubner R. Validity and sensitivity of ratio scales of sensory and affective verbal pain descriptors: manipulation of affect by diazepam. Pain. 1978;5:19-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 247] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Elphick DA, Donnelly MT, Smith KS, Riley SA. Factors associated with abdominal discomfort during colonoscopy: a prospective analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;21:1076-1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |