Published online Apr 21, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4652

Peer-review started: December 23, 2014

First decision: January 22, 2015

Revised: February 10, 2015

Accepted: March 18, 2015

Article in press: March 19, 2015

Published online: April 21, 2015

Processing time: 118 Days and 18.7 Hours

AIM: To explore whether clinician-patient communication affects adherence to psychoactive drugs in functional dyspepsia (FD) patients with psychological symptoms.

METHODS: A total of 262 FD patients with psychological symptoms were randomly assigned to four groups. The patients in Groups 1-3 were given flupentixol-melitracen (FM) plus omeprazole treatment. Those in Group 1 received explanations of both the psychological and gastrointestinal (GI) mechanisms of the generation of FD symptoms and the effects of FM. In Group 2, only the psychological mechanisms were emphasized. The patients in Group 3 were not given an explanation for the prescription of FM. Those in Group 4 were given omeprazole alone. The primary endpoints of this study were compliance rate and compliance index to FM in Groups 1-3. Survival analyses were also conducted. The secondary end points were dyspepsia and psychological symptom improvement in Groups 1-4. The correlations between the compliance indices and the reductions in dyspepsia and psychological symptom scores were also evaluated in Groups 1-3.

RESULTS: After 8 wk of treatment, the compliance rates were 67.7% in Group 1, 42.4% in Group 2 and 47.7% in Group 3 (Group 1 vs Group 2, P = 0.006; Group 1 vs Group 3, P = 0.033). The compliance index (Group 1 vs Group 2, P = 0.002; Group 1 vs Group 3, P = 0.024) with the FM regimen was significantly higher in Group 1 than in Groups 2 and 3. The survival analysis revealed that the patients in Group 1 exhibited a significantly higher compliance rate than Groups 2 and 3 (Group 1 vs Group 2, P = 0.002; Group 1 vs Group 3, P = 0.018). The improvement in dyspepsia (Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 3, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01) and psychological symptom scores (anxiety: Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs Group 3, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01; depression: Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs Group 3, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01) in Group 1 were greater than those in Groups 2-4. The compliance indices were positively correlated with the reduction in symptom scores in Groups 1-3.

CONCLUSION: Appropriate clinician-patient communication regarding the reasons for prescribing psychoactive drugs that emphasizes both the psychological and GI mechanisms might improve adherence to FM in patients with FD.

Core tip: Antianxiety and antidepressant agents are reportedly more effective in the treatment of functional dyspepsia than the regular first-line medications such as proton pump inhibitors and prokinetics. However, their efficacies are greatly hindered by the poor compliance of functional dyspepsia patients. Appropriate clinician-patient communication regarding the reason for prescribing a psychoactive drug that emphasized both the psychological and gastrointestinal mechanisms might improve drug adherence and thus contribute to improvements in their clinical outcomes.

- Citation: Yan XJ, Li WT, Chen X, Wang EM, Liu Q, Qiu HY, Cao ZJ, Chen SL. Effect of clinician-patient communication on compliance with flupentixol-melitracen in functional dyspepsia patients. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(15): 4652-4659

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i15/4652.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i15.4652

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is defined as persistent or recurrent pain or discomfort centered in the upper abdomen without organic diseases and has a prevalence of 8%-23% in Asian populations[1]. Although the pathogenesis of FD remains unclear, epidemiological studies suggest the important role of psychosocial or psychiatric factors, particularly anxiety and depression[2,3]. Accumulating evidence shows that the prevalence of depression and anxiety are higher among FD patients than the general population and patients with organic dyspepsia[4-6].

Antianxiety and antidepressant agents are reportedly more effective in the treatment of FD than the regular first-line medications such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and prokinetics[7-9]. However, the efficacies of antianxiety and antidepressant agents in clinical practice are usually hindered by the poor compliance of patients. It has been reported that approximately 28% and 43% of depressed patients discontinue medications against medical advice in their first and second month of antidepressant therapy, respectively[10,11]. Compliance with psychoactive drug regimens in China is even worse because Chinese people are typically ashamed to admit their psychosocial problems to physicians due to fear of being labeled insane[12]. With regard to FD patients, many refuse to admit that they are experiencing depression or anxiety and thus are resistant to psychoactive medication. Moreover, doctor-patient relationships have become frayed in recent years in China, and many patients distrust doctors[13]. This distrust may be another obstacle to drug compliance among FD patients.

Many factors can affect medication compliance. Inadequate physician-patient communication seems to be the leading cause of poor compliance[14]. In mental health care, improving clinician-patient communication leads to increased patient adherence[15]. With regard to FD patients, many hold the belief that their gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms originate in the GI tract, and thus, they do not need psychoactive medication. In actuality, psychological conditions can strongly affect GI functions, including motor, sensation and secretion functions, and psychoactive drugs might improve dyspepsia symptoms through both central[2] and GI mechanisms[16,17]. Therefore, appropriate clinician-patient communication that provides explanations of the reasons for psychoactive drug prescriptions based on the mechanisms that underlie the generation of FD symptoms and the drugs’ effects might improve compliance with psychoactive agent regimens among FD patients.

It has been reported that the combination of flupentixol and melitracen (FM) has both anxiolytic and antidepressant properties, and has been proven to be safe and effective in the treatment of FD[18]. Flupenthixol is a typical antipsychotic that antagonizes dopamine receptors and 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2 receptors (5-HT2). Melitracen is a tricyclic antidepressant that inhibits the re-uptake of norepinephrine and 5-HT. In the present study, we performed a randomized study to investigate whether appropriate clinician-patient communication could improve compliance to FM treatment among FD patients with anxiety and depression and thus contribute to symptom relief. We also explored the correlation between compliance improvement and symptom relief in these patients.

A total of 327 consecutive patients who were newly diagnosed with FD from May 2013 to April 2014 were recruited from GI outpatient clinics at Renji Hospital. The study was explained to these patients as an evaluation of treatment satisfaction, and the principal purpose of assessing adherence was concealed. After a screening visit, 53 subjects were found to be ineligible for the study, and 12 withdrew. Thus, 262 patients were enrolled. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 18-65 years old; education level no lower than high school; met the ROME III criteria for FD; Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score > 8; absence of abnormalities in physical examination, laboratory tests (including a routine blood test, blood glucose, and liver function examination), abdominal ultrasonography and upper GI endoscopy within 6 mo; and the absence of Helicobacter pylori infection. The exclusion criteria were as follows: known allergy to omeprazole, flupenthixol or melitracen; any evidence of organic digestive diseases; reflux-related symptoms only (e.g., retrosternal pain, burning and regurgitation) or predominantly reflux-related symptoms; severe psychological symptoms that affected life and work; pregnancy or breastfeeding; recent myocardial infarction or cardiac arrhythmias; previous gastric surgery; and the use of PPIs, psychoactive drugs or other drugs that might affect gastric function within 6 mo.

This study was conducted according to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and the requirements of local laws and regulations and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Renji Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the study (Trial registration number: NCT01851863, ClinicalTrials.gov).

The enrolled subjects were randomized into four groups based on computer-generated random number lists. The patients in Groups 1-3 received FM tablets (flupenthixol 0.5 mg and melitracen 10 mg per day; Lundbeck A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) plus omeprazole capsules (20 mg/d; Changzhou Siyao Pharm, Changzhou, China). The one week dose of FM and omeprazole was kept in separate containers for each patient. The patients in Group 4 received omeprazole alone. It is recommended that antidepressant and antianxiety drugs should be taken for a minimum of 6-8 wk at appropriate doses to guarantee their effects in patients with functional gastrointestinal diseases (FGIDs)[19]. Therefore, the treatment period in the present study was set at 8 wk. Six doctors were trained in communicating with the patients according to the following protocols. The patients in Group 1 were told the following: (1) the brain and gut interact with each other, and psychological conditions might affect GI functions and thus contribute to the development of FD symptoms. Therefore, GI symptoms in FD are attributable to both psychological and GI mechanisms; and (2) although FM are psychoactive drugs, they relieve FD symptoms through both psychological and GI mechanisms. In addition to producing improvements in GI functions through central actions, FM can directly modulate GI functions to relieve FD symptoms. The patients in Group 2 were told the following: (1) Their GI symptoms were attributable to somatization of their psychological problems; and (2) FM is an antipsychotic drug and primarily acts centrally to alleviate FD symptoms by regulating the psychological condition. In Group 3, the patients were told only that FM has been proven to be effective in FD treatment and were not provided additional explanations of the relationships between their GI symptoms and their psychological condition and the reasons for the prescription of FM.

The primary endpoint was compliance with the FM treatment. The patients were asked to keep a diary to record their medication intake. Seven days of consecutive abstinence was adopted as the criterion for identifying therapy noncompliance[20]. Moreover, all subjects were asked to return their medication containers each week, and the remaining pills were counted. Those who returned more than 20% of the original pill count were also categorized as noncompliant. The patients lost to follow-up were also considered noncompliant. The compliance rates were calculated by dividing the numbers of compliant patients by the total numbers of enrolled patients in Groups 1-3 after the 8-wk treatment period. The duration of the therapy-compliant period was calculated for each patient and used in the following two analyses[20]: (1) a survival analysis of the number of patients who remained therapy-compliant for each day of the study; and (2) the calculation of a compliance index, which was the ratio of the therapy-compliant period to the total intended treatment period. This index has been suggested to be a more meaningful measure of compliance than the plasma level of the drug[20]. The rate of compliance to omeprazole treatment in Group 4 was also calculated.

The secondary endpoint was symptom relief and included improvements in dyspepsia and psychological symptoms, which were self-reported by all the enrolled subjects from entry to the end of treatment using questionnaires that are described below. The correlations between the compliance indices and the reductions in dyspepsia and psychological symptom scores were also evaluated.

The severity of patients’ dyspeptic symptoms were assessed using the leeds dyspepsia questionnaire (LDQ), which is a reliable, valid and responsive outcome measure for quantifying the frequency and severity of dyspepsia symptoms[21]. The LDQ contains eight items on epigastric pain, retro-sternal pain, regurgitation, nausea, vomiting, belching, early satiety and dysphagia with six grades for each item and an additional item on “the most troublesome symptom” experienced by the subject. LDQ scores of 0-4 were classified as very mild dyspepsia, 4-8 as mild dyspepsia, 9-15 as moderate dyspepsia, and > 15 as severe or very severe dyspepsia[21].

The psychological conditions were evaluated with the HADS, which has been reported to be a valid questionnaire for the assessment of anxiety and depression in the general population[22]. The HADS consists of 14 items, seven of which assess anxiety, and seven assess depression. The patients were asked to answer each item on a four-point (0-3) scale. Scores of 0 to 7 on either subscale can be regarded as within the normal range, scores of 8 to 10 are suggestive of the presence of the respective state, and scores of 11 or higher indicate the probable presence of the respective mood disorder[23]. Both the anxiety and depression scores of all the enrolled patients were > 8 before treatment.

Moreover, the number of participants with adverse reactions was also recorded to analyze the safety profile of treatment.

All enrolled patients in Groups 1-3 were included in the FM compliance analysis. The calculations of the drug efficacies for dyspepsia and the psychological symptoms were based on the intent-to-treat (ITT) population, which included all the subjects in Groups 1-4 who received at least one dose of study medication and underwent a post-treatment assessment, and the last observation carried forward (LOCF) method was employed in cases of premature study termination[24].

Approximately 43% of depressed patients discontinue antidepressant therapy against medical advice after 8 wk in psychiatric primary care[10,11]. Thus, the sample size calculation was based on the assumption that the compliance rates after 8 wk treatment would be 70% in Group 1, 40% in Group 2 and 45% in Group 3 with an α = 0.05 (two-tailed) and a β = 0.20. The estimated sample size was 55 patients per arm; thus, 220 patients were needed to prove that compliance in Group 1 was superior to that in Groups 2 and 3.

SPSS 11.0 software was used to conduct all statistical analyses. Normally distributed data are presented as the mean ± SD. Data from skewed distributions are presented as medians and were analyzed using nonparametric statistics. Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank tests were used to compare the differences between means before and after treatment. One-way ANOVA and the Mann-Whitney test were used to compare the differences between groups. The incidence was compared using the χ2 test, and correlations were assessed with Pearson correlation analysis. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A total of 262 FD patients with psychological symptoms were included and randomly allocated to 4 groups. All groups were well-balanced in terms of demographic and baseline clinical characteristics. The dyspeptic and psychological symptoms prior to treatment were not significantly different between the groups (Table 1). Ten patients did not receive study medication, and 12 were lost to follow-up (Table 2) and thus excluded from the efficacy analysis.

| Groups | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| n | 65 | 66 | 65 | 66 |

| Age (yr) | ||||

| mean ± SD | 46.69 ± 10.74 | 44.16 ± 9.26 | 45.72 ± 10.35 | 46.81 ± 9.82 |

| range | 29-65 | 27-64 | 26-65 | 28-64 |

| Sex ratio, M/F | 1.17 | 1.2 | 1.32 | 1.13 |

| Symptom duration (mo) | 10.15 ± 3.96 | 10.34 ± 3.81 | 9.95 ± 3.72 | 10.23 ± 4.03 |

| LDQ score | 11.85 ± 4.94 | 12.88 ± 4.26 | 12.44 ± 4.91 | 12.33 ± 4.75 |

| HADS score | ||||

| Anxiety | 11.38 ± 3.35 | 11.75 ± 3.26 | 11.12 ± 3.10 | 11.33 ± 3.25 |

| Depression | 12.67 ± 3.30 | 12.45 ± 3.12 | 12.80 ± 3.31 | 12.90 ± 3.03 |

| Groups | Total | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Study entry | 65 | 66 | 65 | 66 | 262 |

| Did not receive study medication | 2 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 10 |

| Lost to follow-up | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 12 |

| Compliance analysis of FM | 65 | 66 | 65 | - | 196 |

| ITT population | 60 | 57 | 60 | 63 | 240 |

The compliance rates after 8 wk of treatment were 67.7% (n = 44/65) in Group 1, 42.4% (n = 28/66) in Group 2 and 47.7% (n = 31/65) in Group 3 [Group 1 vs Group 2: relative risk (RR) = 1.596, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.150-2.214, P = 0.006; Group 1 vs Group 3: RR = 1.419, 95%CI: 1.046-1.926, P = 0.033]. The compliance rate with omeprazole treatment in Group 4 was 90.9% (n = 60/66) after 8 wk of treatment.

The median compliance index was 89.3% for Group 1, which was significantly higher than the indices for Groups 2 (67.0%; estimated P = 0.002) and 3 (73.2%; estimated P = 0.024). There was no significant difference between Groups 2 and 3 (estimated P = 0.463; Mann-Whitney test).

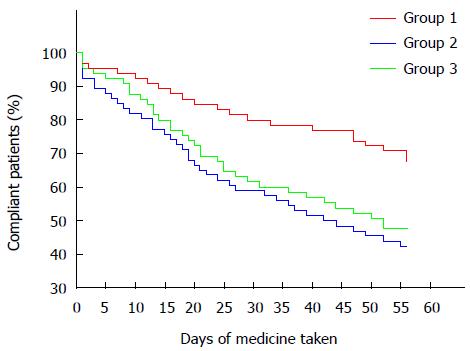

The survival analysis revealed that the patients in Group 1 exhibited a significantly higher compliance rate than did those in Groups 2 and 3 [Group 1 vs Group 2: log rank test χ2 = 9.462, df = 1, P = 0.002, hazard ratio (HR) = 0.444, 95%CI: 0.264-0.745; Group 1 vs Group 3: log rank test χ2 = 5.575, df = 1, P = 0.018, HR = 0.522, 95%CI: 0.304-0.895; Figure 1].

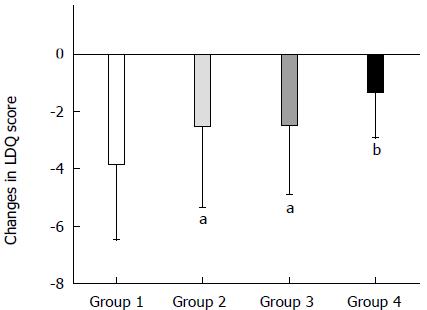

At the end of 8 wk of treatment, the mean LDQ scores of all four groups were reduced compared to the baseline scores (P < 0.01 compared with baseline for each group; Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank tests), and the most dramatic decrease was observed in the patients of Group 1 based on the ITT population (Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 3, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test; Figure 2).

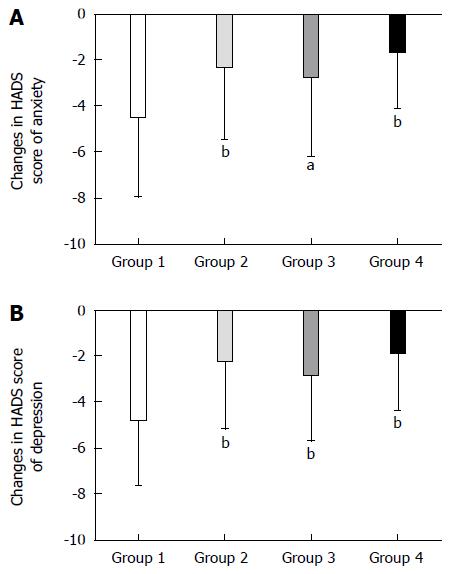

Compared to baseline, the HADS anxiety and depression scores in each of the four groups were decreased after 8 wk of treatment (anxiety: P < 0.01 compared with baseline for each group; depression: P < 0.01 compared with baseline for each group; Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank tests). The patients in Group 1 exhibited the most dramatic decreases (anxiety: Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs 3, P < 0.05; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01; depression: Group 1 vs Group 2, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs Group 3, P < 0.01; Group 1 vs Group 4, P < 0.01; one-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post-test; Figure 3).

Pearson correlation analysis revealed a positive correlation between the compliance index and the reduction in LDQ scores in Groups 1-3. In addition, the reduction in HADS scores for anxiety and depression was positively correlated with the compliance index in these groups (Table 3).

The adverse event rates during the treatment period were 10.0% (6/60), 15.8% (9/57) and 8.3% (5/60) in Groups 1-3, respectively, and no significant differences among groups were observed (χ2 = 5.795, P > 0.05, Table 4). Insomnia, dry mouth and nausea were the most frequently reported events. Adverse events occurred in 3.2% (2/63) of the patients in Group 4. The majority of these adverse events were of mild or moderate intensity and resolved after termination of the study.

| Groups | ||||

| 1 (n = 60) | 2 (n = 57) | 3 (n = 60) | 4 (n = 63) | |

| Insomnia | 3 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Dry mouth | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Nausea | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Skin rash | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

In this study, we showed that appropriate clinician-patient communication regarding the reason for prescribing FM that emphasized both the psychological and GI mechanisms improved adherence to treatment with these drugs among FD patients, and thus contributed to improvements in their clinical outcomes.

Although FD patients who receive antidepressant and antianxiety drugs can exhibit higher response rates than those who receive PPI or prokinetic treatments[7-9], the therapeutic efficacies of psychoactive drugs can be handicapped by poor compliance. FD patients who believe their discomfort originates in the GI tract are usually resistant to psychological diagnoses and antidepressant or antianxiety medications. Therefore, appropriate clinician-patient communication regarding the reasons for prescribing such drugs might improve drug compliance. In the present study, we found that clinician-patient communication which emphasized the notions that FD symptoms are attributable to both psychological and GI mechanisms and that FM relieves FD symptoms via both central and GI mechanisms produced better compliance than emphasizing the psychological mechanisms. These results suggest that appropriate communication regarding the reason for prescribing psychoactive drugs based on the central and GI mechanisms that underlie the generation of FD symptoms and the effect of the drug might help FD patients to understand the necessity of taking FM and improve drug adherence.

The mechanisms underlying FM-induced alleviation of dyspeptic symptoms remain unclear. Accumulating evidence shows that some of the functional GI manifestations might result from somatization of psychiatric disorders[25]. Moreover, psychiatric disorders can be comorbid with GI dysfunction in a subpopulation of FD patients[12]. These psychiatric disorders might elicit or exacerbate GI dysfunction. In such circumstances, FM might help to restore GI function by alleviating mental disorders. Additionally, FM might attenuate GI symptoms by modulating the contents or effects of neurotransmitters in the gut through direct or indirect mechanisms. These neurotransmitters, particularly 5-HT, play important roles in regulating gut function[17,26-28]. These actions of FM provide a theoretical basis for the improvement in dyspeptic symptoms due to the attenuation of drug noncompliance in FD patients.

Because FD patients typically exhibit both GI and psychological symptoms, a combination of a regular first-line therapy (such as PPIs) with psychoactive drugs might yield the best clinical outcomes. Clinical data have demonstrated that psychoactive agents are helpful in alleviating the symptoms of FGIDs[29]. Consistently, we found that 8 wk of treatment with FM plus omeprazole produced more dramatic improvements in the dyspeptic and psychological symptoms of the FD patients than treatment with omeprazole alone.

Moreover, we found that the compliance index was positively correlated with the improvement in clinical outcomes in terms of both dyspeptic and psychological symptoms. These data suggest that the efficacy of FM therapy in FD is associated with patient compliance.

The side effects associated with FM in the present study included insomnia, dizziness and dry mouth. Notably, side effects reported within 1 to 2 wk can lead to drug discontinuation[30]. Initiation of therapy at low doses and closer follow-up, particularly during the first week, might increase compliance[31].

The strengths of the present study include its open-label and prospective design, which had the advantage of permitting the patients to receive treatment as naturally as possible, yielding background rates of noncompliance that were reasonably representative of the population that is treated in actual clinical practice. Therefore, this design provided a more realistic indication of the compliance in clinical settings than would have been achieved with a double-blind study.

The Rome III criteria for FD offer definitions for two subgroups; i.e., the postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) or epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) subgroups. Although we did not allocate the enrolled patients into these two subgroups in this study, we found that both early satiety and epigastric pain, the typical symptom of PDS and EPS, respectively, were significantly improved after FM treatment (data not shown).

In conclusion, this study revealed that appropriate clinician-patient communication regarding the reasons for prescribing psychoactive drugs that emphasizes both psychological and GI mechanisms might improve compliance with FM treatment among FD patients. The improvement in FD symptoms was associated with the patients’ compliance with FM treatment.

Antianxiety and antidepressant agents are reportedly more effective in the treatment of functional dyspepsia (FD) than the regular first-line medications such as proton pump inhibitors and prokinetics. However, the efficacies of antianxiety and antidepressant agents in clinical practice are usually hindered by the poor compliance of patients.

Inadequate physician-patient communication seems to be the leading cause of poor compliance. Many FD patients hold the belief that their gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms originate in the GI tract, and thus, they do not need psychoactive medication. In actuality, psychological condition can strongly affect GI functions, and psychoactive drugs might improve dyspepsia symptoms through both central and GI mechanisms. Therefore, appropriate clinician-patient communication that provides explanations of the reasons for psychoactive drug prescriptions based on the mechanisms that underlie the generation of FD symptoms and the drugs’ effects might improve compliance with psychoactive agent regimens among FD patients.

To date, there is no study exploring drug adherence in FD patients. Thus, this study was carried out to identify an efficient method to improve adherence to antidepressant and antianxiety agents in FD patients. This may be of value in FD therapy.

Appropriate communication regarding the reason for prescribing psychoactive drugs based on the central and GI mechanisms that underlie the generation of FD symptoms and the effect of the drug may help FD patients to understand the necessity of taking FM and improve drug adherence.

Compliance (also referred to as adherence or concordance) describes the degree to which a patient correctly follows medical advice.

This is a nicely designed study to assess the treatment effects of functional dyspepsia using 4 different approaches. The study was appropriately performed, the study interventions are well described, the comparisons of outcome measures between groups adequately described. This article provides new ideas about improving drug adherence and efficacy in FD patients.

P- Reviewer: Lember M, Sarikaya M S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Webster JR E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Ghoshal UC, Singh R, Chang FY, Hou X, Wong BC, Kachintorn U. Epidemiology of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia in Asia: facts and fiction. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:235-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Van Oudenhove L, Aziz Q. The role of psychosocial factors and psychiatric disorders in functional dyspepsia. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:158-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wu JC. Psychological Co-morbidity in Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Management. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2012;18:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mak AD, Wu JC, Chan Y, Chan FK, Sung JJ, Lee S. Dyspepsia is strongly associated with major depression and generalised anxiety disorder - a community study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:800-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Anxiety, depression and quality of life differences between functional and organic dyspepsia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26 Suppl 3:49-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Magni G, di Mario F, Bernasconi G, Mastropaolo G. DSM-III diagnoses associated with dyspepsia of unknown cause. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1222-1223. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Hojo M, Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Ohkusa T, Nagahara A, Kawabe M, Asaoka D, Izumi Y, Sato N. Treatment of functional dyspepsia with antianxiety or antidepressive agents: systematic review. J Gastroenterol. 2005;40:1036-1042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Saad RJ, Chey WD. Review article: current and emerging therapies for functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:475-492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lacy BE, Talley NJ, Locke GR, Bouras EP, DiBaise JK, El-Serag HB, Abraham BP, Howden CW, Moayyedi P, Prather C. Review article: current treatment options and management of functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 12.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lin EH, Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, Simon GE, Walker E, Robinson P. The role of the primary care physician in patients’ adherence to antidepressant therapy. Med Care. 1995;33:67-74. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Maddox JC, Levi M, Thompson C. The compliance with antidepressants in general practice. J Psychopharmacol. 1994;8:48-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhong BL, Chen HH, Zhang JF, Xu HM, Zhou C, Yang F, Song J, Tang J, Xu Y, Zhang S. Prevalence, correlates and recognition of depression among inpatients of general hospitals in Wuhan, China. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chinese doctors are under threat. Lancet. 2010;376:657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hulka BS, Cassel JC, Kupper LL, Burdette JA. Communication, compliance, and concordance between physicians and patients with prescribed medications. Am J Public Health. 1976;66:847-853. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Thompson L, McCabe R. The effect of clinician-patient alliance and communication on treatment adherence in mental health care: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Distrutti E, Fiorucci S, Hauer SK, Pensi MO, Vanasia M, Morelli A. Effect of acute and chronic levosulpiride administration on gastric tone and perception in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:613-622. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Grover M, Camilleri M. Effects on gastrointestinal functions and symptoms of serotonergic psychoactive agents used in functional gastrointestinal diseases. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:177-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hashash JG, Abdul-Baki H, Azar C, Elhajj II, El Zahabi L, Chaar HF, Sharara AI. Clinical trial: a randomized controlled cross-over study of flupenthixol + melitracen in functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27:1148-1155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller RC, Talley NJ. Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders. 3rd ed. McLean: Degnon Associates 2006; . |

| 20. | Thompson C, Peveler RC, Stephenson D, McKendrick J. Compliance with antidepressant medication in the treatment of major depressive disorder in primary care: a randomized comparison of fluoxetine and a tricyclic antidepressant. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:338-343. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Moayyedi P, Duffett S, Braunholtz D, Mason S, Richards ID, Dowell AC, Axon AT. The Leeds Dyspepsia Questionnaire: a valid tool for measuring the presence and severity of dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1257-1262. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361-370. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety And Depression Scale. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1:29. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Shao J, Zhong B. Last observation carry-forward and last observation analysis. Stat Med. 2003;22:2429-2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Nan H, Lee PH, McDowell I, Ni MY, Stewart SM, Lam TH. Depressive symptoms in people with chronic physical conditions: prevalence and risk factors in a Hong Kong community sample. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12:198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tack J, Lee KJ. Pathophysiology and treatment of functional dyspepsia. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:S211-S216. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Talley NJ, Axon A, Bytzer P, Holtmann G, Lam SK, Van Zanten S. Management of uninvestigated and functional dyspepsia: a Working Party report for the World Congresses of Gastroenterology 1998. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13:1135-1148. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Cirillo C, Vanden Berghe P, Tack J. Role of serotonin in gastrointestinal physiology and pathology. Minerva Endocrinol. 2011;36:311-324. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, Bradley LA, Francisconi C, Drossman DA, Creed F. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Thiwan SM, Drossman DA. Treatment of functional GI disorders with psychotropic medicines: A review of evidence with a practical approach. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;2:678-688. |

| 31. | Grover M, Drossman DA. Psychopharmacologic and behavioral treatments for functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009;19:151-170, vii-viii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |