Published online Mar 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3114

Peer-review started: August 18, 2014

First decision: September 15, 2014

Revised: October 17, 2014

Accepted: November 7, 2014

Article in press: November 11, 2014

Published online: March 14, 2015

Processing time: 210 Days and 23 Hours

Enteric intussusception caused by primary intestinal malignant melanoma is a very rare cause of intestinal obstruction. We herein present a case of a 42-year-old female patient with no prior medical history of malignant melanoma, who was admitted with persistent abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A computed tomography scan revealed an intestinal obstruction due to ileocolic intussusception. An emergency laparoscopy and subsequent laparotomy revealed multiple small solid tumors across the whole small bowel. An oncologic resection was not feasible due to the insufficient length of the remaining small bowel. Only a small segment of ileum, which included the largest tumors causing the intussusception, was resected. The pathologic examination revealed two intestinal malignant melanoma lesions. A systematic clinical examination, endoscopic procedures, and fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography scan all failed to reveal any indication of cutaneous, anal, or retinal melanoma. Hence, the tumor was classified as a primary intestinal malignant melanoma with multiple intestinal metastases. Since a complete oncologic resection of tumors was not possible, in order to prevent future intestinal obstruction, a surgical resection of the largest lesions was performed with palliative intention. The epidemiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and management of primary intestinal malignant melanoma, and intestinal intussusception in adults are discussed along with a review of the current literature.

Core tip: We report a case of primary intestinal melanoma presented with an ileocecal intussusception in an adult female patient. Intussusception is an unusual cause of intestinal obstruction in adults with primary intestinal melanoma being a rare intestinal neoplasia. To the best of our knowledge, very few cases of primary intestinal melanoma presenting with enteric intussusception in adults have been reported thus far. In addition to discussing clinical presentations, diagnostics and treatment of the primary intestinal malignant melanoma, and intestinal intussusception in adults, we also performed a comprehensive review of the current literature.

- Citation: Kouladouros K, Gärtner D, Münch S, Paul M, Schön MR. Recurrent intussusception as initial manifestation of primary intestinal melanoma: Case report and literature review. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(10): 3114-3120

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i10/3114.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3114

Enteric intussusception is a rare case of intestinal obstruction in adults, and in most cases it is due to a benign tumor. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the small bowel has been reported as the leading point of enteric intussusception, with primary intestinal melanoma being present in only extremely rare cases. We present a case of a female adult patient with recurrent intestinal intussusceptions due to a primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel.

A 42-year-old female patient was admitted to our emergency department following 12 h of recurrent, intermittent and colicky abdominal pain, accompanied with nausea and vomiting. A similar, but milder, symptomatology was present for approximately two months prior to the admission. The patient’s medical history revealed no prior record of malignant melanoma or any other significant comorbidity. The patient underwent an appendectomy and a caesarian section more than five years earlier. Three weeks prior to being admitted, the patient underwent gastroscopy, a complete colonoscopy, and a comprehensive gynecologic examination. The results of these examinations, along with the outpatient magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the abdomen performed by a private practice one month prior to the admission, revealed no abdominal pathology; therefore, the symptoms were attributed to chronic constipation.

The physical examination revealed a soft, but distended, abdomen with localized tenderness in the right lower quadrant and increased metallic, peristaltic sounds. The laboratory tests showed a mild, normochromic, normocytic anemia, and low serum iron levels.

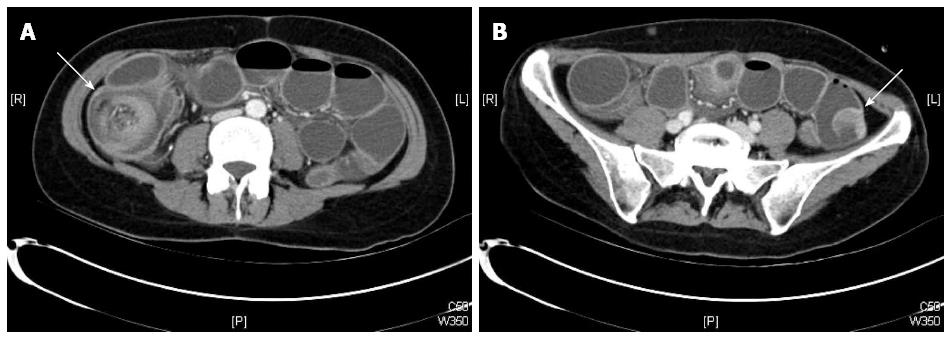

Plain abdominal X-ray revealed central air-fluid levels, and the subsequent computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen showed a mechanic ileus with distention of the whole small intestine. The point of occlusion was at the ileocecal valve. A bowel-within-bowel configuration, typical for ileocolic intussusception, was described, characterized by the presence of the mesenteric fat and vessels around the compressed innermost lumen and surrounding outer enveloping bowel, as well as an intraluminal tumor of the small intestine (Figure 1). Based on the X-ray and CT scan results, an emergency surgery was scheduled. The diagnostic laparoscopy confirmed an ileocecal intussusception as the cause of the mechanic ileus. However, a complete laparoscopic reposition was not feasible; instead, a right pararectal laparotomy was performed. The successful bimanual repositioning revealed two solid tumors, each with a diameter of about 5 cm, 30 cm proximal to the ileocecal valve, as the leading point of the intussusception. The intussusceptum showed an adequate perfusion with no signs of ischemia. A thorough exploration of the small intestine and colon revealed eight additional suspect lesions of smaller size in the small bowel 50-420 cm from the ligament of Treitz. Since the histologic dignity of the tumors was ambiguous, oncologic resection of the lesions was not performed due to possible lack of sufficient length of the remaining small bowel.

A 20-cm-long ileum segment, which included the largest tumors that had led to the intussusception, was resected. The continuity of the gastrointestinal tract was reconstructed with an end-to-end ileoileostomy. The remaining lesions were left behind until histologic examination of the tumor and staging were completed. The postoperative course was uneventful.

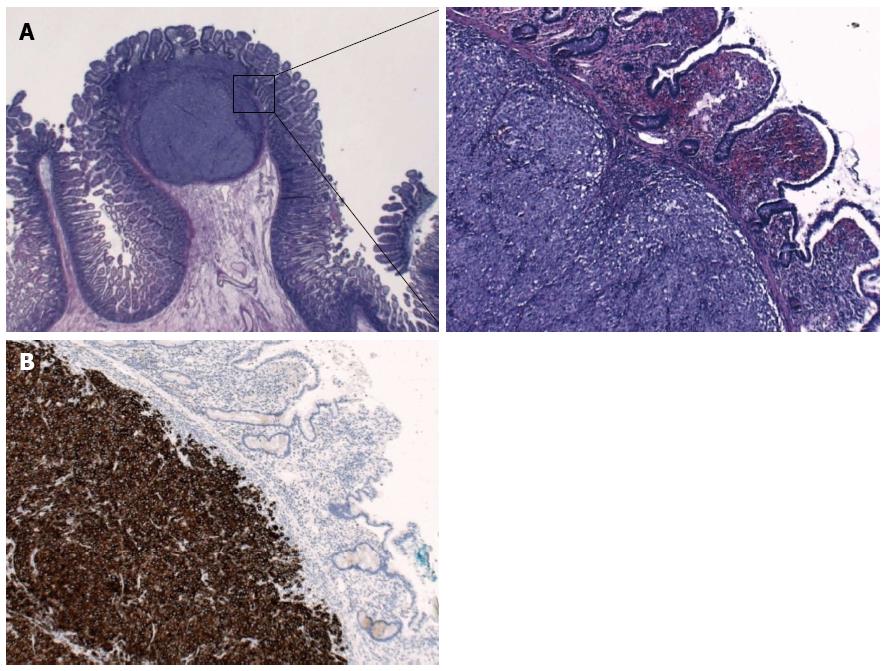

The histopathologic examination revealed two intestinal malignant melanoma lesions with a maximum diameter of 3.5 cm (Figure 2A). Immunohistochemistry revealed tumor cells positive for Melan A, HMB45, S100, and focal for CD117; cells were negative for SMA, AE1/3, dog1, CD56, chromogranin, CD20, and CD30 (Figure 2B). The proliferation fraction (Ki-67-positive) was 90%. Real-time polymerase chain reaction test was negative for V600E mutations of the BRAF gene.

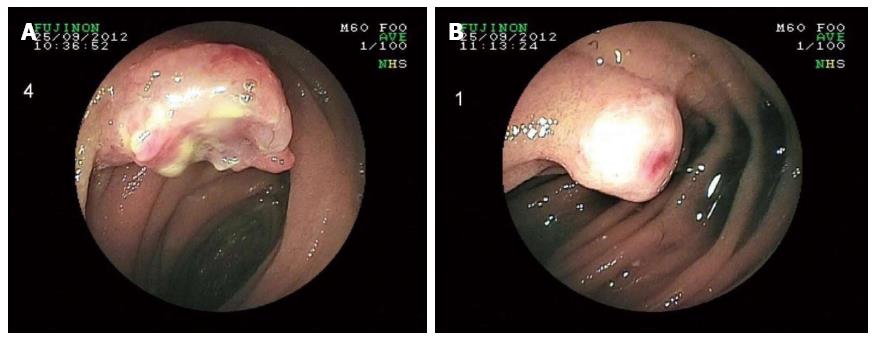

Bearing in mind the histopathologic results, the patient’s medical history was once again carefully reviewed. However, no evidence of malignant melanoma was found. Thorough dermatologic, gynecologic, and ophthalmologic examinations failed to reveal any indication of cutaneous, anal, or retinal melanoma. Double-balloon enteroscopy revealed at least five lesions in the proximal small bowel located 60-180 cm distally from the pyloric valve, whereas the last 70 cm of the ileum was absent of tumors (Figure 3). The detected lesions were endoscopically marked with China ink. A complete enteroscopy attempt was not successful. A fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography (FDG-PET-CT) scan showed at least four intra-abdominal lesions, with a maximum diameter of 2.8 cm, and a nonspecific focal FDG-accumulating lesion adjacent to the left diaphragm. However, there still was no indication of cutaneous, retinal, or anal primary lesions (Figure 4). The tumor was thus classified as a primary intestinal malignant melanoma with multiple intestinal metastases.

The case was discussed at the interdisciplinary Tumor board, and a decision was made to perform a second surgery to resect the lesions identified in the FDG-PET-CT scan and those marked endoscopically, since no extra-abdominal tumor was detected. The second laparotomy revealed a new intussusception of the proximal jejunum caused by a large, palpable tumor approximately 50 cm from the ligament of Treitz. All of the previously marked lesions were identified; at least four additional lesions were palpable in the distal jejunum and the proximal ileum. After a complete manual repositioning, a 7-cm-long jejunum segment, along with the tumor that had led to the second invagination, was resected. A complete intraoperative enteroscopy through the open jejunal lumen revealed multiple smaller, and thus impalpable, metastatic lesions dispersed every 10-15 cm across the whole small bowel. An oncologic resection with complete lymphadenectomy was not feasible due to the insufficient length of the remaining small bowel. Three additional 2-7-cm-long segments containing the largest lesions were resected as a prophylaxis for further invaginations. The histopathologic report identified all the resected lesions as metastases of the previously identified malignant melanoma. The postoperative course was, once again, uneventful, and the patient was discharged seven days post-operation.

The patient was referred to a melanoma reference center for further treatment. Due to the absence of BRAF mutation, a treatment with mitogen-activated protein kinase inhibitors was not implemented; instead, a monotherapy with dacarbazine was performed. A cerebellar metastasis detected three months postoperatively was surgically resected. Despite palliative chemotherapy with ipilimumab, the seven-month postoperative follow-up revealed a progressive intestinal disease, accompanied with multiple pulmonary metastases, a new cerebellar metastasis, and meningitis carcinomatosa. The patient died eight months post-operation due to an advanced, disseminated disease.

First reported in 1674 by Barbette of Amsterdam[1,2], and presented in a detailed report in 1789 by John Hunter[3], intussusception is defined as the telescoping of a proximal segment of the gastrointestinal tract (intussusceptum) into the lumen of the adjacent distal segment (intussuscipiens). Intussusception is the leading cause of intestinal obstruction in children and ranks only second to appendicitis as the most common cause of acute abdominal emergency in pediatric patients[4]. However, the disease is considered to be rare in adults. It has been estimated that adult intussusception represents about 5% of all cases of intussusception, and it accounts for only 1%-5% of intestinal obstruction in adults[5,6]. The most common site for adult intussusception is the small bowel (35%-60%), followed by ileocecal intussusception (24%-35%), and colonic intussusception (15%-26%)[4,7-9].

Intussusception usually presents with acute, subacute, or chronic complaints, with the leading symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting[10]. The symptom duration varies from 6 h to 3 years[7]. The typical clinical triad, pain, palpable abdominal mass and heme-positive stool, is rarely seen in adults[8]. Due to its nonspecific clinical presentation, intussusception is difficult to diagnose, with accuracy rates ranging 30%-90%[5,11-13]. In 35% of the cases, the diagnosis is possible only intraoperatively[4,7].

A typical target sign and pseudo kidney sign seen in abdominal ultrasonography and the bowel-within-bowel configuration in CT scan have been shown to have an accuracy varying from 82%-90%[4,7-9]. However, in some cases of acute intestinal obstruction, these typical signs may be hard to identify in an emergency CT scan due to the severe dilatation of the intestine proximal to the intussusception.

The leading cause of colonic intussusception is usually a malignant tumor, however, the causes of enteric intussusception are benign in 71% of the cases, with lipomas accounting for approximately 27% of the cases, followed by various nontumorous polyps, intestinal inflammatory disease, Meckel’s diverticulum, and previous surgical procedures[9]. Although almost 75% of all tumors of the small bowel are malignant (1/3 primary and 2/3 metastatic)[14], malignant tumors are only detected in 20% of enteric intussusception cases, of which 50% are primary and 50% are metastatic[9].

Among the metastatic intestinal tumors, malignant melanoma ranks fifth (7%) and is considered to be the extraintestinal malignancy with the greatest predilection to metastasize to the bowel. In the gastrointestinal tract, the small bowel is the most frequent site of metastasis of melanoma, mainly because of its rich blood supply[15]. In 58% of the patients with malignant melanoma, intestinal metastases were found at autopsy[16]. However, symptomatic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract is rare among patients with a history of malignant melanoma (approximately 5%) and is most commonly expressed as an acute intestinal obstruction[17]. According to Chiang, malignant melanoma is the most common metastatic tumor to cause an enteric intussusception, sometimes even multiple ones[18]. Such cases have been repeatedly reported in the international literature and in most of these cases the patient had a history of cutaneous malignant melanoma. In several cases, a cutaneous lesion had been resected many years before, and the consequent follow-up was free of tumor manifestations[19-22], whereas other patients were diagnosed with disseminated metastatic disease[23,24].

Small bowel melanoma is a rare disease in adults that is characterized by atypical clinical complaints. Due to the difficulty in exploring the whole length of the small bowel using common diagnostic procedures, a preoperative diagnosis is often challenging to establish[25]. Although different imaging techniques, such as barium examinations, ultrasonography and CT, may be able to depict larger intestinal lesions, these techniques cannot provide information regarding the lesions’ histologic identity[26]. In our case, the abdominal ultrasonography, as well as the MRI scan, failed to show the presence of any of the intra-abdominal lesions, whereas, the emergency CT scan detected only one of the lesions. FDG-PET-CT is a more sensitive procedure that can reveal the largest intestinal lesions, as well as the primary tumor. In our case, many of the intestinal lesions identified intraoperatively were depicted in the FDG-PET-CT, which, nonetheless, still did not reveal any extra-abdominal lesion. The conventional endoscopic procedures (gastroscopy, colonoscopy, double-balloon-enteroscopy) identified some of the tumors. However, these procedures were inadequate for the exploration of the complete length of the small bowel, where most of the melanotic lesions were found. Furthermore, none of the techniques was able to detect any extraluminal lesions. As an alternative, the capsule-enteroscopy can be used to investigate segments of the small bowel not accessible by other endoscopic methods; however, this technique can be only performed electively and does not offer the possibility of biopsy[26,27].

Extraintestinal primary lesions are not found in 5%-26% of the patients with intestinal malignant melanoma[17,28]. Our patient underwent comprehensive dermatologic, gynecologic, and ophthalmologic examination, as well as a complete staging with CT, MRI and FDG-PET-CT scans with no sign of cutaneous, anal, or retinal malignant melanoma. It remains controversial if such cases can be described as primary intestinal melanoma or as metastatic lesions with spontaneous regression of a primary cutaneous melanoma. Mishima[29] postulated that the primary melanoma of the small bowel might arise from Schwannian neuroblast cells associated with the autonomic innervation of the gut. Other authors reported the tumor origin in melanoblastic cells of the neural crest with cells migrating to the distal ileum through the omphalomesenteric canal or in amine precursor uptake decarboxylase cells[30]. On the other hand, a large retrospective study on 103 malignant melanoma cases (77 surgical resections and 26 autopsies) concluded that small bowel involvement by melanoma, even in the absence of any known primary lesion, is usually metastatic from a cutaneous primary lesion that could not be detected[31]. Spontaneous regression of cutaneous malignant melanoma has been reported previously[32,33] and could account for the lack of primary extraintestinal lesion in such cases.

Sachs et al[34] proposed three criteria for diagnosing primary melanoma of the small intestine: (1) histologically proven melanoma of the small intestine at a single focus; (2) no evidence of the disease in any other organs including skin; and (3) a disease-free survival of at least 12 mo after diagnosis. A lesion fulfilling these criteria is likely to be a primary intestinal melanoma. However, these criteria do not allow for detection of already metastasized primary intestinal lesions. Indeed, in several cases of the primary intestinal melanoma, metastatic lesions were detected postoperatively[35-37].

To the best of our knowledge, only seven cases of primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel causing enteric intussusception have been previously reported in the international literature[34-40]. In all cases, the patients had no history of malignant melanoma and were admitted with signs of intestinal obstruction. Although some patients with intussusception were diagnosed preoperatively by ultrasonography or CT scan[35,38-40], in others, the diagnosis could only be set intraoperatively[34,37]. In our case, an emergency CT scan depicted the level of the obstruction and revealed the typical signs of an ileocolic intussusception.

In the reported cases, the cause of intussusception was always a single, solid, intestinal tumor, which was surgically resected and histologically proven to be a malignant melanoma. Clinical examination and imaging failed to reveal any other primary lesion in all of these cases; hence, after a complete surgical resection of the intestinal lesion, the patients were tumor-free. In comparison, our patient had multiple melanotic lesions, found intraoperatively, leading to subsequent intussusceptions, which is characteristic of many metastatic cutaneous melanoma cases. Despite a comprehensive clinical examination and imaging, including FDG-PET-CT scan, there was no indication of an extraintestinal primary lesion. Unlike in other reported cases, an R0-status could not be surgically achieved in our patient. Consequently, the main purpose of the surgical treatment was to resolve the acute intestinal obstruction in the first operation and to prevent an imminent, new intussusception in the second. Palliative surgery of enteric melanoma has been described previously and has been shown to offer a remarkable symptomatic relief with minimal morbidity and mortality, with no apparent effect on the poor overall prognosis[41]. Indeed, our patient reported an immediate regression of the symptoms postoperatively and had no further abdominal complaints, despite the progression of metastatic disease.

Follow-up data have been reported for five patients. In two cases, no signs of recurrence were reported in the 12-mo follow-up[34,39]. Hence, these intestinal melanotic lesions fulfilled the criteria proposed by Sachs et al[34]. However, in the other three cases, despite R0-resection of the intestinal tumor, extraintestinal metastases (hepatic and cerebral) were identified 4-12 mo postoperatively, without any indication of a cutaneous lesion[35-37]. Although these cases did not fit the strict Sachs’ criteria, the intestinal lesions were, nevertheless, officially classified as primary given the lack of evidence for cutaneous, anal, or retinal lesions. The same circumstance was seen in our case, where cerebral metastases and progression of the intestinal tumor were identified, 3 and 7 mo postoperatively, respectively.

In conclusion, primary intestinal malignant melanoma is an unusual tumor of the small bowel. In rare cases, the melanoma can cause enteric intussusception, which is clinically presented as an acute bowel obstruction. Such patients have no previous history of melanoma. Hence, the diagnosis is difficult to make, and is usually established postoperatively based on the histologic findings. Whether primary intestinal melanoma is a true and separate histologic entity, or such tumors are metastases from spontaneously regressed cutaneous, anal or retinal lesions, remains a controversial matter. Imaging techniques are useful in detecting the acute bowel obstruction and may reveal typical signs of intussusception and, in some cases, the intestinal tumors.

A complete surgical resection of the intestinal lesions has been associated with a better overall prognosis. Nevertheless, the palliative role of surgery in resolving an acute bowel obstruction or preventing an imminent one should not be underestimated.

The authors thank Professor, Dr. P Reimer, Professor, Dr. T Rüdiger, Professor, Dr. K Tatsch, Professor, Dr. L Gossner, and Städtisches Klinikum Karlsruhe for their kind permission to use the images included in this paper.

A 42-year-old female patient was presented with recurrent, intermittent, and colicky abdominal pain, accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

Soft, but distended abdomen with localized tenderness in the right lower quadrant and increased metallic peristaltic sounds.

Adhesions, intestinal tumor, intussusception, volvulus.

Mild, normochromic, normocytic anemia; low serum iron levels; metabolic panel, white blood cell count, C-reactive protein, and liver function tests were all within normal limits.

Plain abdominal X-ray revealed central air fluid levels and the subsequent computed tomography of the abdomen showed a mechanic ileus with distention of the whole small intestine, as well as, the typical signs of ileocolic intussusception. Postoperative fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography-computed tomography revealed multiple intra-abdominal lesions, without any indication of primary cutaneous, ocular, or anal melanoma.

Histopathologic examination revealed two intestinal lesions of malignant melanoma with a maximum diameter of 3.5 cm, which were immunohistochemically positive for Melan A, HMB45, S100, focal for CD117, and negative for SMA, AE1/3, dog1, CD56, chromogranin, CD20 and CD30.

The patient underwent two subsequent laparotomies; an initial explorative laparotomy and resection of the tumor that caused the intussusception and, after histologic identification of the tumor, a second laparotomy with palliative resection of the largest lesions, since an R0 resection was not feasible.

The literature has very few cases of primary malignant melanoma presented with enteric intussusception in adults. The exact histologic identification of the tumors, the contribution of the imaging techniques, and the role of surgical treatment are still a matter of discussion.

The term “primary intestinal malignant melanoma” refers to a melanotic lesion in the small intestine in the absence of cutaneous, ocular, or anal primary tumor.

Primary malignant melanoma is a rare cause of enteric intussusception in adults. Defining lesions as primary is still up for debate. Imaging techniques can depict the bowel obstruction, the intussusception, and, in some cases, the intestinal tumors. An R0 resection of the intestinal tumors can be curative; however, the role of palliative surgery should not be underestimated.

The authors report a rare case of enteric intussusception as the first clinical manifestation of primary intestinal malignant melanoma accompanied with a thorough review of the current literature.

P- Reviewer: Galvan-Montano A, Namikawa T, Xu XS S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | de Moulin D. Paul Barbette, M.D.: a seventeenth-century Amsterdam author of best-selling textbooks. Bull Hist Med. 1985;59:506-514. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Barbette P. Oeuvres chirurgiques et anatomiques. In: Miege F, editor. NGeneva: François Miege 1674; . |

| 3. | Noble I. Master surgeon: John Hunter. New York: Messner J 1971; 185. |

| 4. | Wang N, Cui XY, Liu Y, Long J, Xu YH, Guo RX, Guo KJ. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review of 41 cases. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:3303-3308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Azar T, Berger DL. Adult intussusception. Ann Surg. 1997;226:134-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 648] [Cited by in RCA: 666] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zubaidi A, Al-Saif F, Silverman R. Adult intussusception: a retrospective review. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1546-1551. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gupta RK, Agrawal CS, Yadav R, Bajracharya A, Sah PL. Intussusception in adults: institutional review. Int J Surg. 2011;9:91-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gupta V, Doley RP, Subramanya Bharathy KG, Yadav TD, Joshi K, Kalra N, Kang M, Kochhar R, Wig JD. Adult intussusception in Northern India. Int J Surg. 2011;9:297-301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chiang JM, Lin YS. Tumor spectrum of adult intussusception. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:444-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ghaderi H, Jafarian A, Aminian A, Mirjafari Daryasari SA. Clinical presentations, diagnosis and treatment of adult intussusception, a 20 years survey. Int J Surg. 2010;8:318-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang CC, Chen YY, Chen YF, Lin CN, Yen HH, Lou HY. Adult intussusception in Asians: clinical presentations, diagnosis, and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1767-1771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Barussaud M, Regenet N, Briennon X, de Kerviler B, Pessaux P, Kohneh-Sharhi N, Lehur PA, Hamy A, Leborgne J, le Neel JC. Clinical spectrum and surgical approach of adult intussusceptions: a multicentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:834-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Erkan N, Haciyanli M, Yildirim M, Sayhan H, Vardar E, Polat AF. Intussusception in adults: an unusual and challenging condition for surgeons. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2005;20:452-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Minardi AJ, Zibari GB, Aultman DF, McMillan RW, McDonald JC. Small-bowel tumors. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:664-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Gill SS, Heuman DM, Mihas AA. Small intestinal neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:267-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Dasgupta TK, Brasfield RD. Metastatic melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Arch Surg. 1964;88:969-973. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jorge E, Harvey HA, Simmonds MA, Lipton A, Joehl RJ. Symptomatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Operative treatment and survival. Ann Surg. 1984;199:328-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Slaby J, Suri U. Metastatic melanoma with multiple small bowel intussusceptions. Clin Nucl Med. 2009;34:483-485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Harvey KP, Lin YH, Albert MR. Laparoscopic resection of metastatic mucosal melanoma causing jejunal intussusception. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010;20:e66-e68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Gatsoulis N, Roukounakis N, Kafetzis I, Gasteratos S, Mavrakis G. Small bowel intussusception due to metastatic malignant melanoma. A case report. Tech Coloproctol. 2004;8 Suppl 1:s141-s143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Aktaş A, Hoş G, Topaloğlu S, Calık A, Reis A, Pişkin B. Metastatic cutaneous melanoma presented with ileal invagination: report of a case. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16:469-472. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Huang YJ, Wu MH, Lin MT. Multiple small-bowel intussusceptions caused by metastatic malignant melanoma. Am J Surg. 2008;196:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Butte JM, Meneses M, Waugh E, Parada H, De La Fuente H. Ileal intussusception secondary to small bowel metastases from melanoma. Am J Surg. 2009;198:e1-e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alvarez FA, Nicolás M, Goransky J, Vaccaro CA, Beskow A, Cavadas D. Ileocolic intussusception due to intestinal metastatic melanoma. Case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2011;2:118-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Patti R, Cacciatori M, Guercio G, Territo V, Di Vita G. Intestinal melanoma: A broad spectrum of clinical presentation. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2012;3:395-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lens M, Bataille V, Krivokapic Z. Melanoma of the small intestine. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:516-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Prakoso E, Selby WS. Capsule endoscopy in patients with malignant melanoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1204-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wysocki WM, Komorowski AL, Darasz Z. Gastrointestinal metastases from malignant melanoma: report of a case. Surg Today. 2004;34:542-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mishima Y. Melanocytic and nevocytic malignant melanomas. Cellular and subcellular differentiation. Cancer. 1967;20:632-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Amar A, Jougon J, Edouard A, Laban P, Marry JP, Hillion G. [Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16:365-367. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Elsayed AM, Albahra M, Nzeako UC, Sobin LH. Malignant melanomas in the small intestine: a study of 103 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1001-1006. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Doyle JC, Bennett RC, Newing RK. Spontaneous regression of malignant melanoma. Med J Aust. 1973;2:551-552. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Gromet MA, Epstein WL, Blois MS. The regressing thin malignant melanoma: a distinctive lesion with metastatic potential. Cancer. 1978;42:2282-2292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sachs DL, Lowe L, Chang AE, Carson E, Johnson TM. Do primary small intestinal melanomas exist? Report of a case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:1042-1044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Kogire M, Yanagibashi K, Shimogou T, Izumi F, Sugiyama A, Ida J, Mori A, Tamura J, Baba N, Ogawa H. Intussusception caused by primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine. Nihon Geka Hokan. 1996;65:54-59. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Karmiris K, Roussomoustakaki M, Tzardi M, Romanos J, Grammatikakis J, Papadakis M, Polychronaki M, Kouroumalis EA. Ileal malignant melanoma causing intussusception: report of a case. Surg Today. 2007;37:506-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Doğan M, Ozdemır S, Geçım E, Erden E, İçlı F. Intestinal malignant melanoma presenting with small bowel invagination: a case report. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:439-442. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Schoneveld M, De Vogelaere K, Van De Winkel N, Hoorens A, Delvaux G. Intussusception of the small intestine caused by a primary melanoma? Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2012;6:15-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Resta G, Anania G, Messina F, de Tullio D, Ferrocci G, Zanzi F, Pellegrini D, Stano R, Cavallesco G, Azzena G. Jejuno-jejunal invagination due to intestinal melanoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:310-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Patel RB, Vasava NC, Gandhi MB. Acute small bowel obstruction due to intussusception of malignant amelonatic melanoma of the small intestine. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |