Published online Mar 14, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3041

Peer-review started: August 5, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Revised: September 29, 2014

Accepted: December 14, 2014

Article in press: December 16, 2014

Published online: March 14, 2015

Processing time: 223 Days and 22 Hours

AIM: To investigate the electrolyte changes between 2-L polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid 20 g (PEG-Asc) and 4-L PEG solutions.

METHODS: From August 2012 to February 2013, a total of 226 patients were enrolled at four tertiary hospitals. All patients were randomly allocated to a PEG-Asc group or a 4-L PEG. Before colonoscopy, patients completed a questionnaire to assess bowel preparation-related symptoms, satisfaction, and willingness. Endoscopists assessed the bowel preparation using the Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS). In addition, blood tests, including serum electrolytes, serum osmolarity, and urine osmolarity were evaluated both before and after the procedure.

RESULTS: A total of 226 patients were analyzed. BBPS scores were similar and the adequate bowel preparation rate (BBPS ≥ 6) was not different between the two groups (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 73.2% vs 76.3%, P = 0.760). Bowel preparation-related symptoms also were not different between the two groups. The taste of PEG-Asc was better (41.1% vs 16.7%, P < 0.001), and the willingness to undergo repeated bowel preparation was higher in the PEG-Asc group (73.2% vs 59.3%, P = 0.027) than in 4-L PEG. There were no significant changes in serum electrolytes in either group.

CONCLUSION: In this multicenter trial, bowel preparation with PEG-Asc was better than 4-L PEG in terms of patient satisfaction, with similar degrees of bowel preparation and electrolyte changes.

Core tip: Two-liter polyethylene glycol solution with ascorbic acid (PEG-Asc) is widely used as a bowel preparation solution but few studies concern about electrolytes imbalance, especially for Asian population. In this study, we compared PEG-Asc with 4-L PEG and revealed that there were no significant electrolyte changes after intake of solution in the both groups. In addition, the efficacy of bowel preparation by PEG-Asc was equally effective as 4-L PEG and more patients felt better tolerance in PEG-Asc group. Therefore, PEG-Asc can be better option than 4-L PEG.

- Citation: Lee KJ, Park HJ, Kim HS, Baik KH, Kim YS, Park SC, Seo HI. Electrolyte changes after bowel preparation for colonoscopy: A randomized controlled multicenter trial. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(10): 3041-3048

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i10/3041.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i10.3041

Colonoscopy is the current standard method for screening and surveillance of colorectal cancer (CRC)[1]. Colonoscopy is associated with a reduced incidence of CRC through the detection and removal of colorectal adenomas or early colorectal cancer[2]. To achieve these aims, adequate bowel preparation is pivotal and can reduce missed lesions and rescheduled procedures[3,4]. The ideal preparation should be safe and effective in cleaning the colon without damaging its structures or creating an electrolyte imbalance[5]. Patient compliance is also an important factor for adequate bowel preparation. The large volume required and the taste of bowel cleansing solutions are common reasons for poor bowel preparation[6].

High-volume (4-L) polyethylene glycol (PEG) solutions have been widely used and proven to be safe and effective for bowel cleansing[7]. PEG is an isosmotic solution that passes through the bowel without absorption or secretion and is safely used in patients with renal failure, congestive heart failure, and hepatic dysfunction[8]. However, many patients find it unpleasant and are unable to tolerate the large volume and taste[9,10]. Sodium phosphate (NaP) solution can be used in a smaller volume (90 mL) and is well-tolerated. Bowel clearance with NaP is equally effective to 4-L PEG solutions but has safety concerns[11]. The United States Federal Drug Administration publishes a boxed warning on NaP solutions indicating risk of electrolyte imbalance and renal failure.

Recently, a low-volume (2-L) PEG with ascorbic acid 20 g (PEG-Asc, Coolprep®, Taejun Co., Seoul, South Korea) has become available. Several studies have shown that PEG-Asc is safe, effective, and has better compliance and taste compared with 4-L PEG[12-14]. However, there have been few studies comparing electrolyte effects between PEG-Asc and 4-L PEG.

The aim of this trial was to compare PEG-Asc and 4-L PEG with a primary outcome of safety, especially with regard to electrolyte imbalance. In addition, efficacy for bowel preparation and patient compliance were compared between the two groups as secondary outcomes.

This study was a single-blinded, prospective, randomized, controlled multicenter trial in four tertiary hospitals from August 2012 to February 2013. Patients admitted to an outpatient department for elective colonoscopy were enrolled. The indications of colonoscopy were colon cancer screening and functional gastrointestinal symptoms. Exclusion criteria were age younger than 20 years or older than 75 years, gastrointestinal obstruction, severe constipation, previous bowel operation, inflammatory bowel disease, renal failure, heart failure, and pregnancy. The International Review Board for Human Research approved this study (CR312034-003), and written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The sample size was based on appropriate bowel preparation of 4-L PEG although the primary endpoint was electrolyte imbalance. There were difficulty and limitation to calculate the sample size based on several kinds of electrolytes. With an estimated appropriate bowel preparation rate of 75% for 4-L PEG, the effect size was 0.2 and dropout rate was 5%. We planned a sample size of 120 patients for each group.

Patients were randomly assigned to PEG-Asc or 4-L PEG using a computer-generated randomization table sealed in opaque envelopes. All patients were instructed to avoid fiber-rich food, fruit with seeds, and some grains for the three days leading up to the procedure. As split-dose bowel preparation improved quality of bowel preparation in several studies[15,16], a split-dose method was employed in both groups. Patients assigned to PEG-Asc were instructed to ingest 1 L of solution and 500 mL of water the evening before the procedure (up to 21:00 h). The next morning, the last liter was taken with 500 mL of water at least two hours before colonoscopy. Patients assigned to 4-L PEG were instructed to take 3 L of solution the evening before the procedure and 1 L the next morning.

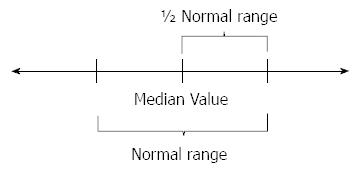

A blood sample was collected from each subject in order to measure sodium, potassium, chloride, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and serum osmolarity before the bowel preparation. The same blood sampling and testing were repeated on the day of colonoscopy, after the bowel preparation was complete. Urine osmolarity also was measured before and after the bowel preparation. We also calculated an “over-changed value,” meaning the changed value of electrolytes exceeding the result of (upper limitation - lower limitation of electrolyte value)/2 (Figure 1).

Patients filled out a questionnaire regarding compliance, satisfaction, and willingness to repeat the preparation solution. Feelings about the bowel preparation solution, its taste, and bowel preparation-related symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, distension, abdominal pain, and dizziness were evaluated.

The endoscopists (six experienced staff members) were blinded to the type of solution used. The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) was used to measure the quality of bowel preparation[17]. The total score was achieved by summing scores for the right segment, transverse segment, and left segment.

All statistical analyses were performed with PASW statistical software (version 13.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Data are presented as mean and standard deviation. T-test was used to compare continuous measures, and χ2 test was used to compare nominal and categorical measures. Changes in laboratory levels before and after bowel preparation were compared within the same group using paired t-test. To assess differences in laboratory levels between the two groups at baseline and after bowel preparation, we performed a linear mixed model for repeated measurements. Two effects were included: one within-group time effect (before and after bowel preparation) and one between-group bowel preparation solution effect. A significant difference was noted when the P-value was ≤ 0.05.

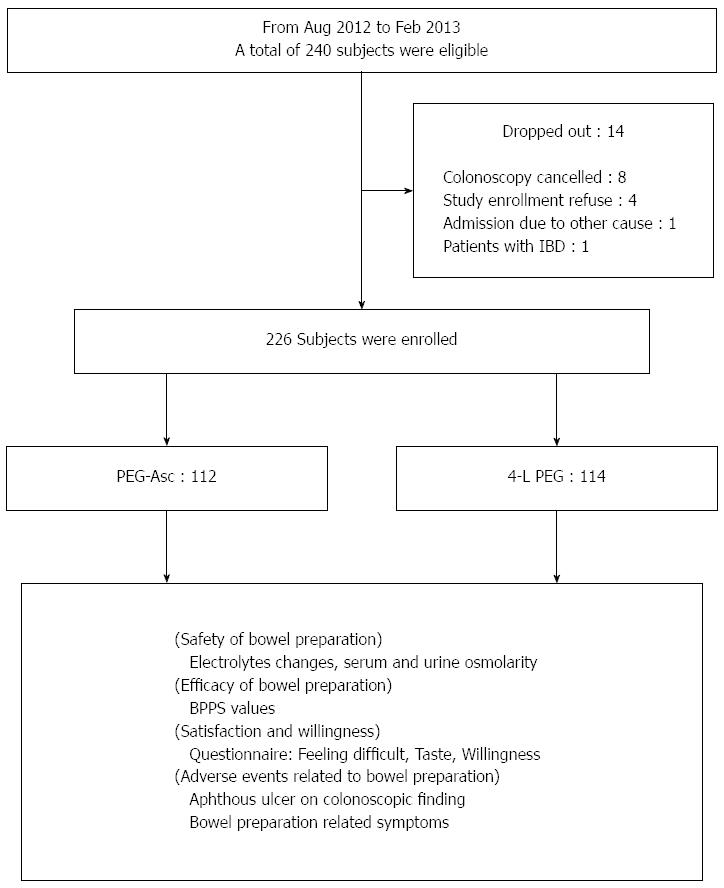

A total of 226 patients (134 men and 92 women) with a median age of 56.5 years were enrolled in this study (Figure 2). The enrolled patients were classified into PEG-Asc (n = 112) and 4-L PEG (n = 114) according to bowel preparation method. Age, sex, colonoscopy history, and number of complete bowel preparation were similar between the two groups. Also, the polyp detection rate and the time of procedure were not different in the two groups. In the PEG-Asc group, colonoscopies were more frequently performed in the morning compared with those of the 4-L PEG group (Table 1).

| PEG-Asc | 4-L PEG | P value | |

| n | 112 | 114 | |

| Age (yr, mean ± SD) | 56 ± 10 | 55 ± 12 | 0.525 |

| Sex (male) | 54.50% | 64% | 0.143 |

| Previous colonoscopy | 55 (49.1) | 58 (50.9) | 0.790 |

| Complete bowel preparation | 112 (100) | 111 (97.4) | 0.247 |

| Morning colonoscopy | 68 (60.7) | 54 (47.4) | 0.044 |

| Indications of colonoscopy | 0.515 | ||

| Colon cancer screening | 65 (58) | 71 (62.3) | |

| Functional GI symptoms | 47 (42) | 43 (37.7) | |

| Polyp detection rate | |||

| Polyp ≥ 1 | 58 (51.8) | 53 (46.5) | 0.506 |

| Procedure time | |||

| Insertion time (min, mean ± SD) | 5.8 ± 4.5 | 5.8 ± 3.3 | 0.938 |

| Withdrawal time (min, mean ± SD) | 9.4 ± 5.5 | 8.4 ± 2.4 | 0.420 |

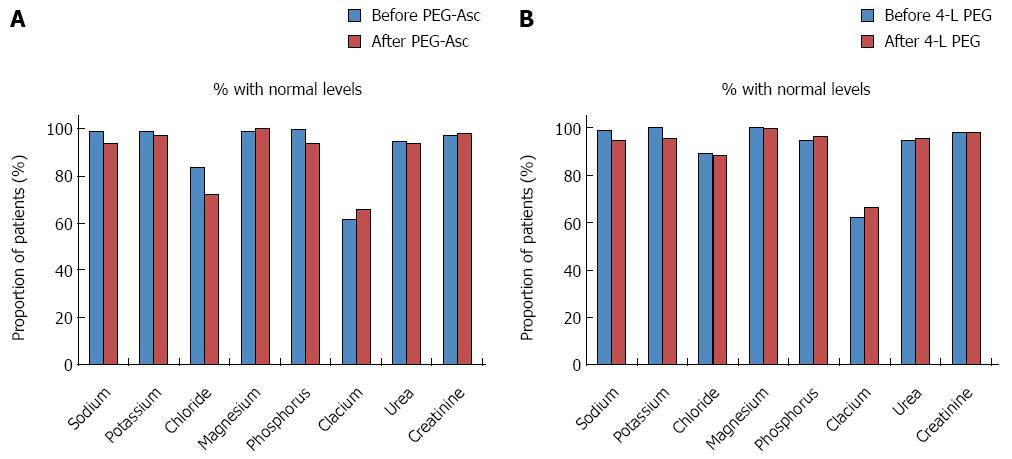

In patients in the PEG-Asc group, sodium, chloride, phosphorus, urea, and urine osmolarity values changed after solution intake. In patients in the 4-L PEG group, sodium, potassium, urea, and urine osmolarity changed after solution intake. Among these, according to linear mixed-model analysis, changes in potassium and phosphorus were significant (Table 2). The level of potassium decreased after intake of 4-L PEG (before: 4.2 ± 0.3 mmol/L, after: 4.0 ± 0.4 mmol/L), and that of phosphorus increased after intake of PEG-Asc (before: 3.4 ± 0.4 mmol/L, after: 3.6 ± 0.5 mmol/L). However, changes in value still fell within the normal range. The proportion of patients with electrolyte levels within the normal ranges were analysed and the number of patients with a chloride level in the normal range were significantly decreased after intake of PEG-Asc (Figure 3). In addition, the proportions of patients with over-changed values were not different in the groups (Table 3).

| PEG-Asc | 4-L PEG | P value1 | |

| Serum | |||

| Sodium | 0.161 | ||

| Before, mmol/L | 140.0 ± 2.4 | 139.8 ± 1.9 | |

| After, mmol/L | 140.8 ± 2.6a | 141.1 ± 2.1a | |

| Potassium | 0.005 | ||

| Before, mmol/L | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | |

| After, mmol/L | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 4.0 ± 0.4a | |

| Chloride | 0.259 | ||

| Before, mmol/L | 103.4 ± 3.3 | 103.2 ± 2.8 | |

| After, mmol/L | 105.3 ± 3.4a | 103.2 ± 3.1 | |

| Magnesium | 0.447 | ||

| Before, mg/dL | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.1 | |

| After, mg/dL | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | |

| Phosphorus | 0.009 | ||

| Before, mg/dL | 3.4 ± 0.4 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | |

| After, mg/dL | 3.6 ± 0.5a | 3.4 ± 0.4 | |

| Calcium | 0.174 | ||

| Before, mg/dL | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 8.9 ± 0.9 | |

| After, mg/dL | 9.7 ± 8.1 | 9.0 ± 0.4 | |

| Urea | 0.624 | ||

| Before, mg/dL | 14.0 ± 4.7 | 13.8 ± 3.4 | |

| After, mg/dL | 13.1 ± 4.6a | 12.6 ± 3.9a | |

| Creatinine | 0.172 | ||

| Before, mg/dL | 1.0 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

| After, mg/dL | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | |

| Serum osmolarity | 0.733 | ||

| Before, mmol/kg | 293.1 ± 31.2 | 291.6 ± 8.2 | |

| After, mmol/kg | 294.4 ± 57.8 | 291.1 ± 11.5 | |

| Urine | |||

| Urine osmolarity | 0.741 | ||

| Before, mmol/L | 633.2 ± 222.1 | 639.7 ± 212.4 | |

| After, mmol/L | 694.4 ± 216.1a | 693.8 ± 183.7a |

| PEG-Asc | 4-L PEG | P value | |

| (n = 112) | (n = 114) | ||

| Na change > 4.5 mmol/L | 7 (6.3) | 14 (12.4) | 0.113 |

| K change > 0.8 mmol/L | 5 (4.5) | 6 (5.3) | 0.769 |

| Ca change > 0.7 mg/dL1 | 4 (3.6) | 4 (3.5) | > 0.999 |

| Mg change > 0.7 mg/dL1 | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0.244 |

| P change > 0.7 mg/dL | 21 (18.8) | 16 (14.0) | 0.338 |

| S osm change > 7.5 mmol/kg | 61 (54.5) | 51 (44.7) | 0.144 |

| Cr change > 0.7 mg/dL | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | > 0.999 |

To compare adequacy of bowel preparation between the two groups, we measured BBPS. Three colonic segments were calculated and summed for a total segment score. The scores showed no significant difference between the two groups (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 7.0 ± 2.1 vs 7.1 ± 2.0, P = 0.601, Table 4). The adequate bowel preparation rate (BBPS ≥ 6) also was not significantly different between the two groups (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 73.2% vs 76.3%, P = 0.760).

| PEG-Asc | 4-L PEG | P value | |

| Right segment | 2.2 ± 0.8 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.175 |

| Transverse segment | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 0.687 |

| Left segment | 2.4 ± 0.8 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.610 |

| Total segment | 7.0 ± 2.1 | 7.1 ± 2.0 | 0.601 |

Bowel preparation solution-related adverse events, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, abdominal distension, thirst, and dizziness, were not different between the two groups. During the procedure, an aphthous ulcer was identified, but there was no difference between the two groups (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 1.8% vs 0.9%, P = 0.620). However, more patients found difficulty taking 4-L PEG than PEG-Asc (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 14.3% vs 30.7%, P = 0.003). The taste of PEG-Asc also was rated significantly better than that of 4-L PEG (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 41.1% vs 16.7%, P < 0.001). More patients in the PEG-Asc group reported that they would undergo the same regimen at their next colonoscopy compared to those in the 4L-PEG group (PEG-Asc vs 4-L PEG, 73.2% vs 59.3%, P = 0.027; Table 5).

| PEG-Asc | 4-L PEG | P value | |

| Adverse events | |||

| Nausea | 32 (28.6) | 34 (29.8) | 0.836 |

| Vomiting | 7 (6.3) | 12 (10.5) | 0.247 |

| Abdominal pain | 11 (9.8) | 10 (8.8) | 0.786 |

| Abdominal distension | 38 (33.9) | 45 (39.5) | 0.387 |

| Thirst | 25 (22.3) | 21 (18.4) | 0.467 |

| Dizziness | 13 (11.6) | 7 (6.1) | 0.148 |

| Aphtous ulcer | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0.620 |

| Subjective feelings | |||

| Feel difficult | 16 (14.3) | 35 (30.7) | 0.003 |

| Taste “good” | 46 (41.1) | 19 (16.7) | < 0.001 |

| Willingness | 82 (73.2) | 67 (59.3) | 0.027 |

Adequate bowel preparation is needed to improve the quality of colonoscopy. With the advent of several bowel preparation solutions, numerous studies have performed comparisons for safety, efficacy, and compliance[7,8,18]. Poor preparation is associated with missed polyps, interval cancer, and increased hospital costs[19,20]. Also, the risk of procedure-related complications, such as bowel perforation, is increased with inadequate preparation[21]. PEG is the most widely used bowel preparation solution and is safely used even in patients with serum electrolyte imbalance, acute kidney injury, hepatic dysfunction, and congestive heart failure[11]. However, the large volume (4-L) necessary and taste are major limitations[22]. Sodium phosphate (NaP) is a hyperosmotic purgative with a small-volume requirement that has been shown to be equally effective to 4-L PEG, but side effects such as electrolyte imbalance and nephrotoxicity are among its major problems[11]. Recently, PEG-Asc has been developed as a low-volume (2-L) bowel preparation solution. According to several studies comparing its efficacy and safety with those of other solutions, PEG-Asc is as effective, safe, and acceptable as 4-L PEG[14,18,23]. However, there are few studies concerning safety issues, especially evaluating electrolyte imbalance and renal function, after intake of PEG-Asc. Therefore, we focused on electrolyte changes and renal function before and after bowel preparation between the two groups.

We used the commercial bowel preparation solution PEG-Asc (PEG-Asc, Coolprep®, Taejun Co., Seoul, South Korea) containing 200 g of polyethylene glycol, 15 g of sodium sulfate, 5.4 g of sodium chloride, 2 g of potassium chloride, and 20 g of vitamin C. The administration of high-dose ascorbic acid (up to 30 g) is known to be less related with such as renal stone, abdominal pain, and severe acidosis[24]. Unabsorbed vitamin C can act as an osmotic agent because of its hexose structure[25,26] and a single high dose of vitamin C can lead to decreased absorption because of time-constrained intestinal absorption[27]. The use of high-dose ascorbic acid remains unsure due to its risk of acid-base and electrolyte imbalance. Among the possible problems related to electrolyte imbalance caused by PEG-Asc include are acid-base imbalance due to a high dose of ascorbic acid, hyponatremia from dehydration, and specific electrolyte imbalances, such as hyperphosphatemia, resulting in hypocalcemia followed by renal impairment.

Mathus-Vliegen et al[26] compared the efficacy and safety, including electrolyte balance, of 4-L PEG and a small volume (2 L) of PEG with 20 g of ascorbic acid. In their study, serum calcium, chloride, and osmolarity levels were increased in the 4-L PEG group in contrast with a decreased serum bicarbonate level in the PEG-Asc group. Mouly et al[28] used different doses of ascorbic acid with PEG to show increased serum sodium, potassium, and bicarbonate concentration after use of PEG with 20 g of Asc. Recently, Rex’s study comparing a reduced dose of oral sulfate solution followed by 2 L of sulfate-free electrolyte lavage solution (PEG-ELS) with PEG-ELS plus ascorbic acid showed decreased serum bicarbonate, sodium, potassium, and phosphate levels in the PEG-ELS group with ascorbic acid[29]. All of the above studies, however, noted that such electrolyte imbalance did not lead to clinical problems.

Our study produced increased serum potassium, chloride, calcium, and phosphate concentrations after bowel cleansing with PEG-Asc, which different slightly from previous studies. In addition, we evaluated the over-changed values of electrolyte [(upper limitation-lower limitation)/2] to account for highly altered levels of electrolytes. The proportions of patients with over-changed values were high with regard to phosphorus (18.8%), sodium (6.3%), potassium (4.5%), and calcium (3.6%). However, there were no electrolyte imbalances requiring urgent intervention. In particular, our study showed that increased phosphorus level was more commonly observed in the PEG-Asc group than in the 4-L PEG group. In contrast with NaP solution, PEG-Asc does not contain phosphorus components, and the increased rate of phosphorus was less than 10% in this group (about 50% of that seen with NaP). Therefore, there was no remarkable consequent change in serum calcium level with fatal complication such as nephrocalcinosis[30,31].

In spite of substantial changes in electrolytes, there were no constant patterns of change through a few studies including our study. We assume that electrolyte changes after intake of PEG-Asc are transient and minor, and recovery from these changes could be easily achieved by homeostatic mechanisms. Further study is needed in patients with renal impairment whose renal homeostatic mechanisms are compromised.

With regard to bowel-preparation efficacy and compliance, the bowel preparation by PEG-Asc was equally as effective as that by the 4L-PEG solution, results compatible with previous studies[12-14,26]. Mathus-Vliegen et al[26] compared the efficacy of PEG-Asc and 4-L PEG and reported that endoscopists preferred 4-L PEG for its significantly better bowel cleansing in the right and transverse colon compared with PEG-Asc. In the PEG-Asc group, the patients ingested an additional 2 L of water. In our study, the bowel preparation by PEG-Asc was equally as effective as 4-L PEG in all segments of bowel despite the ingestion of only an additional 1 L of water in the PEG-Asc group. In addition, patients with PEG-Asc experienced less difficulty and better taste with the ingested solution than did those in the 4-L PEG group. As PEG-Asc is a low-volume (2-L) solution that tastes like lemon, more patients in the PEG-Asc group preferred to repeat the same regimen at their next examination compared to those in the 4-L PEG group. Other adverse events, such as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, were not different between the two groups. In addition, there were no clinically significant changes in electrolytes or renal function observed in this study.

The strength of this study is that it is the first examination of electrolyte changes caused by PEG-Asc in an Asian population with a reasonable sample size. The major limitation of this study is the inability to measure the level of plasma vitamin C concentration as ascorbic acid may disturb acid-base balance. The exclusion of patients with renal failure, congestive heart failure, and hepatic dysfunction is a potential limitation. Patients with renal or heart failure may be influenced by electrolyte changes and there were safety concerns. As this study was to compare the safety on electrolyte balance, we excluded those patients with high risk. A large-scale and well-designed study is needed to ensure that PEG-Asc is safe in patients with these medical conditions.

In conclusion, in this multicenter trial, bowel preparation with PEG-Asc was a better option than 4-L PEG in terms of patient satisfaction and demonstrated similar degrees of bowel preparation and electrolyte changes.

A low-volume (2-L) polyethylene glycol with ascorbic acid 20 g (PEG-Asc) is safe and effective as 4-L PEG. However, there are few studies concerning electrolyte changes after intake of PEG-Asc.

To investigate the electrolyte changes after intake of PEG-Asc or 4-L PEG.

There were no electrolytes changes requiring intervention after intake of PEG-Asc or 4-L PEG. In addition, the bowel preparation of PEG-Asc was effective as 4-L PEG and more patients felt better tolerance in PEG-Asc group.

This present study suggests that PEG-Asc is safe in terms of electrolytes changes in Asian population. Also, PEG-Asc is more tolerable and as effective as 4-L PEG, providing a better option in patients’ compliance for colonoscopic bowel preparation.

This is an interesting study. However the authors will need to elaborate more on the methodology including how the patients were randomized, what are the primary and secondary outcome measures. How the sample size was calculated. Was the blinding of the allocation and the assessors. Only after all these vital information is provided can this be published.

P- Reviewer: Madhoun MF, Tan KY, Teramoto-Matsubara OT S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Nelson RS, Thorson AG. Colorectal cancer screening. Curr Oncol Rep. 2009;11:482-489. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Nishihara R, Wu K, Lochhead P, Morikawa T, Liao X, Qian ZR, Inamura K, Kim SA, Kuchiba A, Yamauchi M. Long-term colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after lower endoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1095-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 968] [Cited by in RCA: 1158] [Article Influence: 96.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim WH, Cho YJ, Park JY, Min PK, Kang JK, Park IS. Factors affecting insertion time and patient discomfort during colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:600-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rex DK, Imperiale TF, Latinovich DR, Bratcher LL. Impact of bowel preparation on efficiency and cost of colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1696-1700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Toledo TK, DiPalma JA. Review article: colon cleansing preparation for gastrointestinal procedures. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:605-611. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ness RM, Manam R, Hoen H, Chalasani N. Predictors of inadequate bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1797-1802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 322] [Cited by in RCA: 343] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 7. | Ell C, Fischbach W, Keller R, Dehe M, Mayer G, Schneider B, Albrecht U, Schuette W; Hintertux Study Group. A randomized, blinded, prospective trial to compare the safety and efficacy of three bowel-cleansing solutions for colonoscopy (HSG-01*). Endoscopy. 2003;35:300-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lichtenstein G. Bowel preparations for colonoscopy: a review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66:27-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hayes A, Buffum M, Fuller D. Bowel preparation comparison: flavored versus unflavored colyte. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2003;26:106-109. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Radaelli F, Meucci G, Imperiali G, Spinzi G, Strocchi E, Terruzzi V, Minoli G. High-dose senna compared with conventional PEG-ES lavage as bowel preparation for elective colonoscopy: a prospective, randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2674-2680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Belsey J, Epstein O, Heresbach D. Systematic review: adverse event reports for oral sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:15-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Di Palma JA, Rodriguez R, McGowan J, Cleveland Mv. A randomized clinical study evaluating the safety and efficacy of a new, reduced-volume, oral sulfate colon-cleansing preparation for colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2275-2284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jansen SV, Goedhard JG, Winkens B, van Deursen CT. Preparation before colonoscopy: a randomized controlled trial comparing different regimes. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:897-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ponchon T, Boustière C, Heresbach D, Hagege H, Tarrerias AL, Halphen M. A low-volume polyethylene glycol plus ascorbate solution for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy: the NORMO randomised clinical trial. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:820-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Menees SB, Kim HM, Wren P, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Elta GH, Foster S, Korsnes S, Graustein B, Schoenfeld P. Patient compliance and suboptimal bowel preparation with split-dose bowel regimen in average-risk screening colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:811-820.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Park SS, Sinn DH, Kim YH, Lim YJ, Sun Y, Lee JH, Kim JY, Chang DK, Son HJ, Rhee PL. Efficacy and tolerability of split-dose magnesium citrate: low-volume (2 liters) polyethylene glycol vs. single- or split-dose polyethylene glycol bowel preparation for morning colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1319-1326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lai EJ, Calderwood AH, Doros G, Fix OK, Jacobson BC. The Boston bowel preparation scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:620-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 930] [Cited by in RCA: 925] [Article Influence: 57.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Clark RE, Godfrey JD, Choudhary A, Ashraf I, Matteson ML, Bechtold ML. Low-volume polyethylene glycol and bisacodyl for bowel preparation prior to colonoscopy: a meta-analysis. Ann Gastroenterol. 2013;26:319-324. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hendry PO, Jenkins JT, Diament RH. The impact of poor bowel preparation on colonoscopy: a prospective single centre study of 10,571 colonoscopies. Colorectal Dis. 2007;9:745-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hong SN, Sung IK, Kim JH, Choe WH, Kim BK, Ko SY, Lee JH, Seol DC, Ahn SY, Lee SY. The Effect of the Bowel Preparation Status on the Risk of Missing Polyp and Adenoma during Screening Colonoscopy: A Tandem Colonoscopic Study. Clin Endosc. 2012;45:404-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Froehlich F, Wietlisbach V, Gonvers JJ, Burnand B, Vader JP. Impact of colonic cleansing on quality and diagnostic yield of colonoscopy: the European Panel of Appropriateness of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy European multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:378-384. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Golub RW, Kerner BA, Wise WE, Meesig DM, Hartmann RF, Khanduja KS, Aguilar PS. Colonoscopic bowel preparations--which one? A blinded, prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:594-599. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Valiante F, Pontone S, Hassan C, Bellumat A, De Bona M, Zullo A, de Francesco V, De Boni M. A randomized controlled trial evaluating a new 2-L PEG solution plus ascorbic acid vs 4-L PEG for bowel cleansing prior to colonoscopy. Dig Liver Dis. 2012;44:224-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Gentile M, De Rosa M, Cestaro G, Forestieri P. 2 L PEG plus ascorbic acid versus 4 L PEG plus simethicon for colonoscopy preparation: a randomized single-blind clinical trial. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:276-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Aihara H, Saito S, Arakawa H, Imazu H, Omar S, Kaise M, Tajiri H. Comparison of two sodium phosphate tablet-based regimens and a polyethylene glycol regimen for colon cleansing prior to colonoscopy: a randomized prospective pilot study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2009;24:1023-1030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mathus-Vliegen EM, van der Vliet K. Safety, patient’s tolerance, and efficacy of a 2-liter vitamin C-enriched macrogol bowel preparation: a randomized, endoscopist-blinded prospective comparison with a 4-liter macrogol solution. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1002-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Xing JH, Soffer EE. Adverse effects of laxatives. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1201-1209. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Mouly S, Mahé I, Knellwolf AL, Simoneau G, Bergmann JF. Effects of the addition of high-dose vitamin C to polyethylene glycol solution for colonic cleansing: A pilot study in healthy volunteers. Curr Ther Res Clin Exp. 2005;66:486-500. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Rex DK, McGowan J, Cleveland Mv, Di Palma JA. A randomized, controlled trial of oral sulfate solution plus polyethylene glycol as a bowel preparation for colonoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:482-491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Afridi SA, Barthel JS, King PD, Pineda JJ, Marshall JB. Prospective, randomized trial comparing a new sodium phosphate-bisacodyl regimen with conventional PEG-ES lavage for outpatient colonoscopy preparation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:485-489. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Jeong S, Lee SG, Kim Y, Park JR, Kim JH. Differences in clinical chemistry values according to the use of two laxatives for colonoscopy. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:1047-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |