Published online Jan 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.326

Peer-review started: June 19, 2014

First decision: July 21, 2014

Revised: August 8, 2014

Accepted: September 18, 2014

Article in press: September 19, 2014

Published online: January 7, 2015

Processing time: 202 Days and 19.6 Hours

AIM: To elucidate the association between small bowel diseases (SBDs) and positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB).

METHODS: Between February 2008 and August 2013, 202 patients with OGIB who performed both capsule endoscopy (CE) and FOBT were enrolled (mean age; 63.6 ± 14.0 years, 118 males, 96 previous overt bleeding, 106 with occult bleeding). All patients underwent immunochemical FOBTs twice prior to CE. Three experienced endoscopists independently reviewed CE videos. All reviews and consensus meeting were conducted without any information on FOBT results. The prevalence of SBDs was compared between patients with positive and negative FOBT.

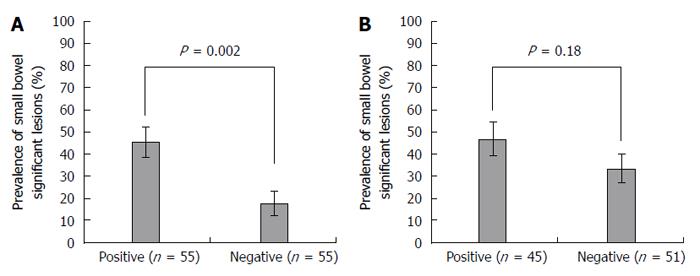

RESULTS: CE revealed SBDs in 72 patients (36%). FOBT was positive in 100 patients (50%) and negative in 102 (50%). The prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in patients with positive FOBT than those with negative FOBT (46% vs 25%, P = 0.002). In particular, among patients with occult OGIB, the prevalence of SBDs was higher in positive FOBT group than negative FOBT group (45% vs 18%, P = 0.002). On the other hand, among patients with previous overt OGIB, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between positive and negative FOBT group (47% vs 33%, P = 0.18). In disease specific analysis among patients with occult OGIB, the prevalence of ulcer and tumor were higher in positive FOBT group than negative FOBT group. In multivariate analysis, only positive FOBT was a predictive factors of SBDs in patients with OGIB (OR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.4-4.6, P = 0.003). Furthermore, the trend was evident among patients with occult OGIB who underwent FOBT on the same day or a day before CE. The prevalence of SBDs in positive vs negative FOBT group were 54% vs 13% in patients with occult OGIB who underwent FOBT on the same day or the day before CE (P = 0.001), while there was no significant difference between positive and negative FOBT group in those who underwent FOBT two or more days before CE (43% vs 25%, P = 0.20).

CONCLUSION: The present study suggests that positive FOBT may be useful for predicting SBDs in patients with occult OGIB. Positive FOBT indicates higher likelihood of ulcers or tumors in patients with occult OGIB. Undergoing CE within a day after FOBT achieved a higher diagnostic yield for patients with occult OGIB.

Core tip: We investigated the association between small bowel diseases (SBDs) and a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB). Positive FOBT may be useful for predicting SBDs in patients with occult OGIB. Positive FOBT indicates higher likelihood of ulcers or tumors in patients with occult OGIB. Undergoing capsule endoscopy within a day after FOBT achieved a higher diagnostic yield for patients with occult OGIB.

- Citation: Kobayashi Y, Watabe H, Yamada A, Suzuki H, Hirata Y, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Koike K. Impact of fecal occult blood on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: Observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(1): 326-332

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i1/326.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.326

The fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is widely accepted as a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening tool, and several large cohort trials have shown a reduction in CRC mortality with use of the FOBT[1-7]. The FOBT detects occult bleeding from colorectal lesions, although it is assumed that the FOBT may also detect occult bleeding from small bowel diseases (SBDs). However, the usefulness of FOBT in detecting bleeding from the small bowel remains unknown.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) and balloon-assisted enteroscopy are now available for assessing SBDs in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB)[8-19]. Diagnosis of OGIB is made by excluding patients with a bleeding source which could be found by esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy[20]. OGIB is classified as either overt or occult OGIB. Occult OGIB is defined as iron-deficiency anemia (IDA) and/or a positive FOBT of unknown origin after EGD and colonoscopy[21]. Although a positive FOBT is a component of an occult OGIB diagnosis, the association between FOBT and SBDs remains unknown.

In the present study, we investigated the association between SBDs and a positive FOBT in patients with OGIB.

We conducted a retrospective analysis in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki with the approval of the ethical committee of the University of Tokyo (Tokyo, Japan). The aim was to investigate the association between FOBT and SBDs detected by CE in patients with OGIB.

Between February 2008 and August 2013, we enrolled 202 patients with OGIB who underwent CE and FOBT. OGIB was defined as recurrent or persistent overt/visible bleeding, IDA, or a positive FOBT with no bleeding source found at the initial endoscopic evaluation[20]. OGIB was classified as overt or occult OGIB. Overt OGIB was defined as clinically perceptible bleeding that recurred or persisted after a negative initial endoscopic evaluation by EGD and colonoscopy. In comparison, occult OGIB was defined as IDA, with or without a positive FOBT[21]. IDA was diagnosed when all of the following criteria were fulfilled; hemoglobin (Hb) < 13.5 g/dL, serum ferritin < 65 ng/dL, mean corpuscular volume < 80 fL and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration < 28 pg.

FOBTs were performed for patients with occult OGIB or previous overt OGIB. Patients with clinically perceptible bleeding at the time of the FOBT were excluded. Patients with a cardiac pacemaker, past history of bowel obstruction, or refusal to provide written informed consent were also excluded.

CE was performed using Pillcam® SB or SB2 (Given Imaging Ltd., Yoqneam, Israel). The preparation for CE involved fasting for 12 h and administration of 40 mg simethicone just before CE. Eating was allowed 5 h after CE ingestion. During the examination, patients could move freely. Sensor array and recording devices were removed 8 h after CE ingestion.

Three experienced endoscopists independently reviewed the CE images using Rapid® 5 Access software (Given Imaging Ltd., Yoqneam, Israel) or Rapid® 6.5 Access software. The reading speed of the CE videos was 15-20 frames per second in the dual-view mode. The endoscopists were blinded to the FOBT results and an independent review was held to reach a consensus on the CE findings.

All study patients underwent immunochemical FOBTs (Eiken Chem, Tokyo, Japan) prior to CE. Two tubes were collected for FOBT, if possible. A positive test was accepted at a threshold of 100 ng/mL for the higher reading of the two tubes.

The prevalence of SBDs was compared between patients with positive and negative FOBTs. We analyzed an association between the FOBT and the prevalence of each SBD, such as erosion, ulcer, angiectasia, tumor or active bleeding. We also analyzed the association between the timing of the FOBT and the prevalence of SBDs.

All statistical analyses were performed using the JMP 10 statistical software program (SAS Institute Inc., North Carolina, United States). In all analyses, means were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test. Frequency distributions were compared using Fisher’s exact probability test or χ2 test. Multivariate analysis was conducted using multivariate unconditional logistic regression analysis. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Baseline clinical characteristics of the study patients are summarized in Table 1. A total of 202 OGIB patients (mean age 63.6 ± 14.0 years; 118 males) received both CE and FOBT during the study period. Ninety-six patients (48%) had previous overt OGIB and 106 patients (52%) occult OGIB. The FOBT was positive in 100 (50%) and negative in 102 (50%) patients. The time discrepancy between the FOBT and CE was similar for overt and occult OGIB (11.9 vs 5.3 d, P = 0.09). CE revealed significant lesions of the small bowel in 72 patients (36%), identified as ulcers in 13 (6%), erosions in 37 (18%), angiectasias in 22 (11%), tumors in 8 (4%) and active bleeding in 19 (9%) patients. There were some patients that had several types of SBD simultaneously. The mean of the three kappa values (reviewer A vs B, A vs C, B vs C) was 0.9.

| Characteristic | |

| Age (yr)1 | 63.6 ± 14.0 |

| Gender (Male/Female) | 118 (58)/84 (42) |

| Indications of CE | |

| Previous overt OGIB | 96 (48) |

| Occult OGIB | 106 (52) |

| FOBT | |

| Positive FOBT | 100 (50) |

| Negative FOBT | 102 (50) |

| The time discrepancy between the FOBT and CE | 8.5 (0-156) d |

| CE findings of the small bowel2 | |

| Ulcer | 13 (6) |

| Erosion | 37 (18) |

| Angiectasia | 22 (11) |

| Tumor | 8 (4) |

| Active bleeding | 19 (9) |

| Daily using drugs | |

| NSAIDs | 18 (9) |

| Aspirin | 44 (22) |

| % of capsule obtained cecum image | 83% |

| Blood test1 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.6 ± 2.3 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 17.5 ± 10.6 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.25 ± 1.69 |

| Serum iron (μg/dL) | 65.7 ± 56.2 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 95.4 ± 20.1 |

A comparison of baseline characteristics between the positive and negative FOBT groups is summarized in Table 2. Between the two groups, there was no significant difference in the number of patients using drugs such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), aspirin or warfarin daily. There was no significant difference in the levels of hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, serum iron or ferritin between the positive and negative FOBT groups.

| Positive FOBT(n = 100) | Negative FOBT(n = 102) | P value | |

| Age (yr)1 | 65.3 ± 14.1 | 61.9 ± 13.8 | 0.08 |

| Daily using drugs2 | |||

| NSAIDs | 7 (7) | 11 (11) | 0.35 |

| Aspirin | 24 (24) | 20 (20) | 0.45 |

| Warfarin | 14 (14) | 11 (11) | 0.49 |

| Blood test1 | |||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.4 ± 2.5 | 10.9 ± 2.1 | 0.17 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 19.0 ± 12.1 | 16.2 ± 8.9 | 0.07 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.46 ± 1.88 | 1.04 ± 1.48 | 0.08 |

| Serum iron (μg/dL) | 67.9 ± 57.1 | 63.5 ± 55.4 | 0.62 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 88.8 ± 22.0 | 90.6 ± 17.7 | 0.58 |

The prevalence of SBDs in the positive and negative FOBT groups is shown in Table 3. The prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in patients with a positive FOBT than in those with a negative FOBT (46% vs 25%; OR = 2.5; 95%CI: 1.4-4.5; P = 0.002). In the disease-specific analysis, the prevalences of ulcers and active bleeding were higher in patients with a positive FOBT. The prevalence of ulcers in the small bowel was significantly higher in the positive FOBT group than the negative FOBT group (11% vs 2%; OR = 6.2; 95%CI: 1.30-28.6; P = 0.009). Similarly, the prevalence of active bleeding was significantly higher in the positive FOBT group than the negative FOBT group (15% vs 4%; OR = 4.3; 95%CI: 1.4-13.5; P = 0.007). There was no significant difference in the prevalence of erosions, angiectasias or tumors between the positive and negative FOBT groups.

| Positive FOBT(n = 100) | Negative FOBT(n = 102) | P value | |

| Any small bowel lesions (n = 72) | 46 (46) | 25 (25) | 0.002 |

| Ulcer (n = 13) | 11 (11) | 2 (2) | 0.009 |

| Erosion (n = 37) | 21 (21) | 16 (16) | 0.330 |

| Angiectasia (n = 22) | 14 (14) | 8 (8) | 0.160 |

| Tumor (n = 8) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 0.450 |

| Active bleeding (n = 19) | 15 (15) | 4 (4) | 0.007 |

When patients were divided into occult and previous overt OGIB groups, a significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between positive and negative FOBTs was found in the occult OGIB group only (Figure 1). Among patients with occult OGIB, the prevalence of SBDs was higher in the positive FOBT group than the negative FOBT group (45% vs 18%; OR = 3.9; 95%CI: 1.6-9.5; P = 0.002). In other words, the mean sensitivity and specificity of FOBT for SBDs in the occult OGIB group were 74% and 42%, respectively, while the accuracy of FOBT for SBDs in the occult OGIB group was 63%. In contrast, among patients with previous overt OGIB, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between the positive and negative FOBT groups (47% vs 33%; OR = 1.8; 95%CI: 0.8-4.0; P = 0.18).

The association between FOBT and each SBD was analyzed (Table 4). In patients with occult OGIB, the prevalence of ulcers, tumors and active bleeding were significantly higher in the positive FOBT group than the negative FOBT group (7% vs 0% for ulcers, P = 0.049; 7% vs 0% for tumors, P = 0.049; 13% vs 0% for active bleeding, P = 0.008, respectively), while there was no significant difference in the prevalence of erosions and angiectasias between the positive and negative FOBT groups.

| Positive FOBT patients with occult OGIB(n = 55) | Negative FOBT patients with occult OGIB(n = 51) | P value | |

| Ulcer | 4 (7) | 0 | 0.049 |

| Erosion | 11 (20) | 7 (14) | 0.390 |

| Angiectasia | 9 (16) | 4 (8) | 0.180 |

| Tumor | 4 (7) | 0 | 0.049 |

| Active bleeding | 7 (13) | 0 | 0.008 |

Table 5 summarizes the results from the univariate analysis of predictive factors for SBDs in patients with OGIB. Among age, gender, FOBT, OGIB (overt or occult), hemoglobin level (≤ 10.6 g/dL or > 10.6 g/dL), NSAIDs, aspirin and/or other anticoagulants, only positive FOBT was a significant factor (P = 0.002). Overt OGIB and a hemoglobin level ≤ 10.6 g/dL had P values < 0.3. Multivariate analysis using these three factors revealed that only a positive FOBT was an independent predictive factor for SBDs in patients with OGIB (OR = 2.5; 95%CI: 1.4-4.6; P = 0.003) (Table 6).

| Factor | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Age (yr) | |||

| > 64 | 1.2 | 0.67-2.2 | 0.52 |

| ≤ 64 | 1 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1 | ||

| Female | 1.1 | 0.61-2.0 | 0.75 |

| FOBT | |||

| Positive | 2.5 | 1.4-4.5 | 0.002 |

| Negative | 1 | ||

| OGIB | |||

| Overt | 1.4 | 0.78-2.5 | 0.27 |

| Occult | 1 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | |||

| ≤ 10.6 | 1.5 | 0.81-2.6 | 0.21 |

| > 10.6 | 1 | ||

| Medication | |||

| NSAIDs | 0.67 | 0.23-2.0 | 0.47 |

| Aspirin and/or other anticoagulants | 0.83 | 0.45-1.6 | 0.57 |

| Factor | OR | 95%CI | P value |

| Positive FOBT | 2.5 | 1.4-4.6 | 0.003 |

| Overt OGIB | 1.4 | 0.78-2.6 | 0.25 |

| Hemoglobin level ≤ 10.6 g/dL | 1.2 | 0.68-2.3 | 0.48 |

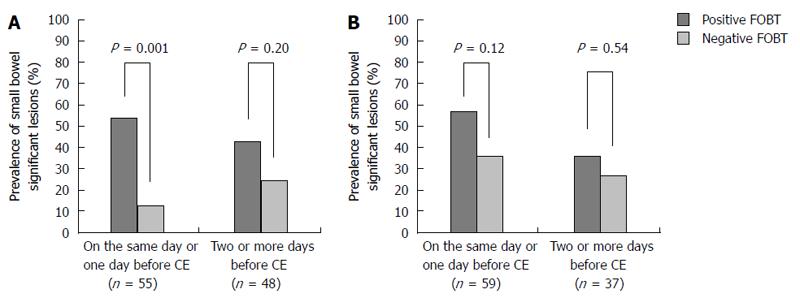

We analyzed the timing of FOBT and the prevalence of SBDs. The average duration between FOBT and CE was 8.5 d (0-129 d). We divided the study patients based on those who underwent FOBT on the same day or the day before CE (n = 114) vs those who underwent FOBT 2 or more days before CE (n = 85). The prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in the positive than the negative FOBT group among patients who underwent FOBT on the same day or the day before CE (55% vs 24%, P = 0.0007). In contrast, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between the positive and negative FOBT groups among patients who underwent FOBT 2 or more days before CE (40% vs 28%, P = 0.24).

Among patients with occult OGIB who underwent FOBT on the same day or the day before CE, the prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in the positive than the negative FOBT group (54% vs 13%, P = 0.001), while there was no significant difference between the positive and negative FOBT groups in those who underwent FOBT 2 or more days before CE (43% vs 25%, P = 0.20) (Figure 2). In contrast, among patients with previous overt OGIB, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between the positive and negative FOBT groups, regardless of the FOBT timing.

The present study estimated the association between the prevalence of SBDs and the FOBT in patients with OGIB. The study revealed that the prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in patients with a positive FOBT than in those with a negative FOBT among patients with OGIB. Multivariate analysis revealed that a positive FOBT was an independent predictive factor for SBDs in patients with OGIB (OR = 2.5, 95%CI: 1.4-4.6, P = 0.003). Although a positive FOBT comprises part of the definition of occult OGIB, the clinical impact of FOBT on SBDs has not been elucidated. The present study indicated that a positive FOBT was useful for predicting the presence of SBDs in patients with occult OGIB. Furthermore, in disease-specific analysis, the prevalence of ulcers, tumors and active bleeding were significantly higher in the positive than the negative FOBT group among patients with occult OGIB, while there was no significant difference in the prevalence of erosions or angiectasias. It is assumed that ulcers and tumors undergo continuous bleeding, which can be detected by FOBT, while erosions and angiectasias do not bleed constantly, and some additional factors such as anticoagulant drugs or hypertension could provoke bleeding intermittently[22-24].

The association between the FOBT and the prevalence of SBDs in OGIB patients remains to be determined. Levi et al[25] studied the association between FOBT and SBDs among patients with occult OGIB. Ten of 26 patients with SBDs had a positive FOBT, while only 2 of 25 patients without SBDs had a positive FOBT. They concluded that significant lesions detected by CE in the small bowel could explain a positive FOBT, similar to the results found here. On the other hand, Chiba et al[26] assessed the small bowel using CE in asymptomatic FOBT-positive patients with a negative colonoscopy. Among 53 asymptomatic patients with a positive FOBT and a negative colonoscopy, there were no findings of a high potential for bleeding, which does not agree with the outcomes presented here. There were differences between the study designs. Our study included patients with previous overt OGIB and occult OGIB, while only asymptomatic patients with a positive FOBT were included in the work by Chiba et al[26] Moreover, the mean blood Hb level was 10.6 ± 2.3 g/dL in our study and 14.1 ± 1.6 g/dL in that of Chiba et al[26] study. We predict that the patients included in our study had a higher potential for significant lesions in the gastrointestinal tract.

The present study also showed that the timing of the FOBT influences the association between FOBT and the prevalence of SBDs. It is assumed that CE should be performed on the same day or 1 d after a positive FOBT in patients with occult OGIB, which is similar to what is recommended for patients with overt OGIB. Yamada et al[27] reported that performing CE within 2 d after the latest bleeding event resulted in a higher diagnostic yield for patients with overt OGIB. In addition, Pennazio et al[10] reported that the diagnostic yield of CE was significantly higher in patients with ongoing overt OGIB than in patients with previous overt OGIB. Our study confirmed that performing CE soon after the positive FOBT result was important for obtaining an accurate diagnosis. Thus, the utility of FOBT may decrease as time passes.

The potential limitations of our study should be noted. We used the immunochemical FOBT, rather than the guaiac-based FOBT, because the former is the only test available in Japan. Several papers reported that the sensitivity of the immunochemical FOBT for upper gastrointestinal lesions is low[28-30]. However, patients with positive guaiac-based FOBT who undergo colonoscopy and have no significant lesions are often advised to undergo upper endoscopy, since bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract can result in a positive guaiac-based FOBT[31-33]. Any differences in the detection of small bowel bleeding between immunochemical and guaiac-based FOBTs have not been reported. Second, the study was retrospective. A prospective study is needed to draw definitive conclusions regarding the impact of FOBT on OGIB. Third, the time discrepancy between the FOBT and CE was prolonged at 8.5 d. Since the study patients were not experiencing ongoing bleeding, the medical urgency for them was low, which likely caused the time discrepancy between the FOBT and CE.

In conclusion, the present study showed that the prevalence of SBDs was higher in the positive FOBT group than the negative FOBT group among patients with occult OGIB. Thus, a positive FOBT is an independent risk factor of SBDs, and CE should be performed within 1 d after a positive FOBT for optimal results.

Although several large cohort trials have shown a reduction in colorectal cancer mortality with use of the fecal occult blood test (FOBT), the usefulness of FOBT for detection on bleeding from the small bowel is unknown. Capsule endoscopy (CE) is now available for assessing small bowel diseases (SBDs) in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) or patients who have possibilities for SBDs. Although a positive FOBT is a component of an occult OGIB diagnosis, the association between FOBT and SBDs detected by CE remains unknown.

FOBT is widely used for colorectal cancer screening and several large cohort trials have shown a reduction in colorectal cancer mortality with use of FOBT. CE is now available for assessing SBDs in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding or patients who have possibilities for SBDs. CE makes a large contribution to following examinations or therapies for SBDs.

In this study, the authors investigated the association between SBDs and a positive FOBT in patients with OGIB. The prevalence of SBDs was significantly higher in patients with positive FOBT than those with negative FOBT. In particular, among patients with occult OGIB, the prevalence of SBDs was higher in positive FOBT group than negative FOBT group, while there was no significant difference in the prevalence of SBDs between positive and negative FOBT group among patients with previous overt OGIB. Furthermore, undergoing CE within a day after FOBT achieved a higher diagnostic yield for patients with occult OGIB.

The study results suggest that positive FOBT may be useful for predicting SBDs in patients with occult OGIB and undergoing CE may be performed within a day after FOBT.

The authors investigated the association between SBDs and a positive FOBT in patients with OGIB. The prevalence of SBDs was higher in positive FOBT group than negative FOBT group in patients with occult OGIB (45% vs 18%, P = 0.002). Positive FOBT may be useful for predicting SBDs in patients with occult OGIB. Positive FOBT indicates higher likelihood of ulcers or tumors in patients with occult OGIB. Undergoing CE within a day after FOBT achieved a higher diagnostic yield for patients with occult OGIB.

P- Reviewer: Chen JQ, Hauser G, Lee HW, Wang K S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Hardcastle JD, Chamberlain JO, Robinson MH, Moss SM, Amar SS, Balfour TW, James PD, Mangham CM. Randomised controlled trial of faecal-occult-blood screening for colorectal cancer. Lancet. 1996;348:1472-1477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1858] [Cited by in RCA: 1830] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mandel JS, Bond JH, Church TR, Snover DC, Bradley GM, Schuman LM, Ederer F. Reducing mortality from colorectal cancer by screening for fecal occult blood. Minnesota Colon Cancer Control Study. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1365-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2174] [Article Influence: 67.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Kronborg O, Fenger C, Olsen J, Jørgensen OD, Søndergaard O. Randomised study of screening for colorectal cancer with faecal-occult-blood test. Lancet. 1996;348:1467-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1640] [Cited by in RCA: 1601] [Article Influence: 55.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F, Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, Snover DC, Schuman LM. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1603-1607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 940] [Cited by in RCA: 966] [Article Influence: 38.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kewenter J, Brevinge H, Engarås B, Haglind E, Ahrén C. Results of screening, rescreening, and follow-up in a prospective randomized study for detection of colorectal cancer by fecal occult blood testing. Results for 68,308 subjects. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:468-473. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Scholefield JH, Moss SM, Mangham CM, Whynes DK, Hardcastle JD. Nottingham trial of faecal occult blood testing for colorectal cancer: a 20-year follow-up. Gut. 2012;61:1036-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shaukat A, Mongin SJ, Geisser MS, Lederle FA, Bond JH, Mandel JS, Church TR. Long-term mortality after screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1106-1114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 646] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Iddan G, Meron G, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Nature. 2000;405:417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1994] [Cited by in RCA: 1385] [Article Influence: 55.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Yamamoto H, Sekine Y, Sato Y, Higashizawa T, Miyata T, Iino S, Ido K, Sugano K. Total enteroscopy with a nonsurgical steerable double-balloon method. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:216-220. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Pennazio M, Santucci R, Rondonotti E, Abbiati C, Beccari G, Rossini FP, De Franchis R. Outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding after capsule endoscopy: report of 100 consecutive cases. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:643-653. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Apostolopoulos P, Liatsos C, Gralnek IM, Kalantzis C, Giannakoulopoulou E, Alexandrakis G, Tsibouris P, Kalafatis E, Kalantzis N. Evaluation of capsule endoscopy in active, mild-to-moderate, overt, obscure GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:1174-1181. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Urbain D, De Looze D, Demedts I, Louis E, Dewit O, Macken E, Van Gossum A. Video capsule endoscopy in small-bowel malignancy: a multicenter Belgian study. Endoscopy. 2006;38:408-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Fukumoto A, Tanaka S, Shishido T, Takemura Y, Oka S, Chayama K. Comparison of detectability of small-bowel lesions between capsule endoscopy and double-balloon endoscopy for patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:857-865. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Heine GD, Hadithi M, Groenen MJ, Kuipers EJ, Jacobs MA, Mulder CJ. Double-balloon enteroscopy: indications, diagnostic yield, and complications in a series of 275 patients with suspected small-bowel disease. Endoscopy. 2006;38:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 295] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 14.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Marmo R, Rotondano G, Casetti T, Manes G, Chilovi F, Sprujevnik T, Bianco MA, Brancaccio ML, Imbesi V, Benvenuti S. Degree of concordance between double-balloon enteroscopy and capsule endoscopy in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding: a multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2009;41:587-592. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | May A, Nachbar L, Ell C. Double-balloon enteroscopy (push-and-pull enteroscopy) of the small bowel: feasibility and diagnostic and therapeutic yield in patients with suspected small bowel disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:62-70. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Mönkemüller K, Weigt J, Treiber G, Kolfenbach S, Kahl S, Röcken C, Ebert M, Fry LC, Malfertheiner P. Diagnostic and therapeutic impact of double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006;38:67-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shinozaki S, Yamamoto H, Yano T, Sunada K, Miyata T, Hayashi Y, Arashiro M, Sugano K. Long-term outcome of patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding investigated by double-balloon endoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:151-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Raju GS, Gerson L, Das A, Lewis B. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute technical review on obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1697-1717. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Leighton JA, Goldstein J, Hirota W, Jacobson BC, Johanson JF, Mallery JS, Peterson K, Waring JP, Fanelli RD, Wheeler-Harbaugh J. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:650-655. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Yamada A, Sugimoto T, Kondo S, Ohta M, Watabe H, Maeda S, Togo G, Yamaji Y, Ogura K, Okamoto M. Assessment of the risk factors for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:116-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tan VP, Yan BP, Kiernan TJ, Ajani AE. Risk and management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with prolonged dual-antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2009;10:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Albert JG, Schülbe R, Hahn L, Heinig D, Schoppmeyer K, Porst H, Lorenz R, Plauth M, Dollinger MM, Mössner J. Impact of capsule endoscopy on outcome in mid-intestinal bleeding: a multicentre cohort study in 285 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20:971-977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Levi Z, Gal E, Vilkin A, Chonen Y, Belfer RG, Fraser G, Niv Y. Fecal immunochemical test and small bowel lesions detected on capsule endoscopy: results of a prospective study in patients with obscure occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23:1024-1028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Chiba H, Sekiguchi M, Ito T, Tsuji Y, Ohata K, Ohno A, Umezawa S, Takeuchi S, Hisatomi K, Teratani T. Is it worthwhile to perform capsule endoscopy for asymptomatic patients with positive immunochemical faecal occult blood test? Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:3459-3462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yamada A, Watabe H, Kobayashi Y, Yamaji Y, Yoshida H, Koike K. Timing of capsule endoscopy influences the diagnosis and outcome in obscure-overt gastrointestinal bleeding. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:676-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Rockey DC, Auslander A, Greenberg PD. Detection of upper gastrointestinal blood with fecal occult blood tests. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:344-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Harewood GC, McConnell JP, Harrington JJ, Mahoney DW, Ahlquist DA. Detection of occult upper gastrointestinal tract bleeding: performance differences in fecal occult blood tests. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:23-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Levi Z, Vilkin A, Niv Y. Esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy is not indicated in patients with positive immunochemical test and nonexplanatory colonoscopy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22:1431-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Rockey DC, Koch J, Cello JP, Sanders LL, McQuaid K. Relative frequency of upper gastrointestinal and colonic lesions in patients with positive fecal occult-blood tests. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:153-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Hsia PC, al-Kawas FH. Yield of upper endoscopy in the evaluation of asymptomatic patients with Hemoccult-positive stool after a negative colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:1571-1574. [PubMed] |