Published online Jan 7, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.262

Peer-review started: May 16, 2014

First decision: June 18, 2014

Revised: June 30, 2014

Accepted: July 29, 2014

Article in press: July 30, 2014

Published online: January 7, 2015

Processing time: 235 Days and 16.3 Hours

AIM: To retrospectively analyze factors affecting the long-term survival of patients with pancreatic cancer who underwent pancreatic resection.

METHODS: From January 2000 to December 2011, 195 patients underwent pancreatic resection in our hospital. The prognostic factors after pancreatic resection were analyzed in all 195 patients. After excluding the censored cases within an observational period, the clinicopathological characteristics of 20 patients who survived ≥ 5 (n = 20) and < 5 (n = 76) years were compared. For this comparison, we analyzed the patients who underwent surgery before June 2008 and were observed for more than 5 years. For statistical analyses, the log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative survival rates, and the χ2 and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare the two groups. The Cox-Hazard model was used for a multivariate analysis, and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. A multivariate analysis was conducted on the factors that were significant in the univariate analysis.

RESULTS: The median survival for all patients was 27.1 months, and the 5-year actuarial survival rate was 34.5%. The median observational period was 595 d. With the univariate analysis, the UICC stage was significantly associated with survival time, and the CA19-9 ≤ 200 U/mL, DUPAN-2 ≤ 180 U/mL, tumor size ≤ 20 mm, R0 resection, absence of lymph node metastasis, absence of extrapancreatic neural invasion, and absence of portal invasion were favorable prognostic factors. The multivariate analysis showed that tumor size ≤ 20 mm (HR = 0.40; 95%CI: 0.17-0.83, P = 0.012) and negative surgical margins (R0 resection) (HR = 0.48; 95%CI: 0.30-0.77, P = 0.003) were independent favorable prognostic factors. Among the 96 patients, 20 patients survived for 5 years or more, and 76 patients died within 5 years after operation. Comparison of the 20 5-year survivors with the 76 non-survivors showed that lower concentrations of DUPAN-2 (79.5 vs 312.5 U/mL, P = 0.032), tumor size ≤ 20 mm (35% vs 8%, P = 0.008), R0 resection (95% vs 61%, P = 0.004), and absence of lymph node metastases (60% vs 18%, P = 0.036) were significantly associated with the 5-year survival.

CONCLUSION: Negative surgical margins and a tumor size ≤ 20 mm were independent favorable prognostic factors. Histologically curative resection and early tumor detection are important factors in achieving long-term survival.

Core tip: The prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients remains quite poor. In this study, however, the 5-year actuarial survival rate was much higher (34.5%) than normal. Histologically curative resection and early tumor detection were important factors in achieving long-term survival.

- Citation: Yamamoto T, Yagi S, Kinoshita H, Sakamoto Y, Okada K, Uryuhara K, Morimoto T, Kaihara S, Hosotani R. Long-term survival after resection of pancreatic cancer: A single-center retrospective analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(1): 262-268

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i1/262.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.262

Pancreatic cancer is the fourth leading cause of death among all types of cancer, accounting for 6% of men and 7% of women who died of cancer in the United States in 2010. The prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer remains quite poor, with a 5-year survival rate of only 6%[1]. Surgery remains the only curative treatment for pancreatic cancer. Only 10%-20% of the patients with pancreatic cancer could be candidates for surgical resection in previous reports[2,3]. In 1984, the 5-year survival rate after surgery was only 3%. However, patient prognosis has been improving, and the 5-year survival rate after surgery has been approximately 11%-25% in the last decade[4-7]. This improvement may be attributable to the increased experience of surgeons performing pancreatic resection and possibly to the effects of adjuvant chemotherapy.

Several studies have reported prognostic factors after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer. The significant prognostic factors identified are tumor size, lymph node metastasis, surgical margin status, tumor markers, and adjuvant chemotherapy[5,8-10]. This study was designed to analyze the factors prognostic of survival in patients with pancreatic cancer and the characteristics of long-term survivors.

From January 2000 to December 2011, 195 patients with pancreatic cancer in our hospital underwent pancreatic resection, consisting of a standard operation without extended lymphadenectomy[11]. We first analyzed the prognostic factors after pancreatic resection for all 195 patients. We then assessed the clinicopathological characteristics of the 96 patients who underwent surgery on or before June 2008 and who were followed-up for > 5 years. Of these 96 patients, 20 patients survived ≥ 5 years, and 76 patients died within 5 years. The clinicopathological characteristics of these two subgroups were analyzed. The analysis of extrapancreatic neural invasion and portal invasion followed the Japan Pancreas Society (JPS) classification[12].

The protocol for the present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital. The informed consents were waived because the study consisted of a historical cohort.

The values are presented as the mean ± SD, medians (interquartile range), or numbers and percentages. The log-rank test was used to compare the cumulative survival rates, and the χ2 and Mann-Whitney tests were used to compare the two groups. The Cox-Hazard model was used for the multivariate analysis, and P values less than 0.05 were considered significant. A multivariate analysis was conducted using the factors that were significant in the univariate analysis. Cutoff values were determined using receiver operating characteristic curves, except that for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), which was determined to be the upper limit of normal. The normal ranges of tumor markers in our hospital are CEA ≤ 5.0 ng/mL, CA19-9 ≤ 37.0 U/mL and DUPAN-2 ≤ 150 U/mL. CEA and CA19-9 were measured by chemiluminescence enzyme immunoassay, and DUPAN-2 was by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The 195 patients consisted of 108 males and 87 females (mean age 68 ± 8.1 years at the time of pancreatic resection) (Table 1). Median and interquartile range of tumor marker concentrations were carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) 2.8 (1.7-4.8) ng/mL, carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) 143.5 (29.3-435.3) U/mL, and pancreatic cancer-associated antigen (DUPAN-2) 182 (31.0-739.3) U/mL. There were a few patients who didn’t undergo examination of tumor marker, and their data of tumor markers were missing. Of the 195 patients, 145 (74%) had lymph node metastases, 108 (55%) had extrapancreatic neural invasion, and 63 (32%) had portal invasion. The union for International Cancer Control (UICC) pathological stage[13] was IA in nine patients (4.6%); IB in one patient (0.5%); IIA in 38 patients (19.5%); IIB in 110 patients (56.4%); III in nine patients (4.6%); and IV in 28 patients (14.4%). Of the 195 patients, 123 patients (63%) underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy; 61 patients (31%) underwent distal pancreatectomy; and 11 patients (6%) underwent total pancreatectomy. The surgical margin status was negative (R0) in 138 patients (71%); microscopically positive (R1) in 50 patients (26%); and grossly positive (R2) in 7 patients (4%). One hundred fifty patients (77%) received postoperative chemotherapy for an average of 208 d. During chemotherapy, 142 patients received gemcitabine; six patients received tegafur-gimeracil-oteracil potassium (S1); and two patients received other regimens. The average time from operation to the initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy was 54.9 d. Adjuvant radiation therapy was not used for any patient.

| Variables | Value (n = 195) |

| Age, mean ± SD | 67.6 ± 8.1 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 108 |

| Female | 87 |

| Tumor marker, median (IQR) | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.8 (1.7-4.8) |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 143.5 (29.3-435.3) |

| DUPAN-2 (U/mL) | 182 (31.0-739.3) |

| Operative procedures, n | |

| Pancreaticoduodenectomy | 123 |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 61 |

| Total pancreatectomy | 11 |

| UICC T classification, n | |

| T1 | 10 |

| T2 | 6 |

| T3 | 168 |

| T4 | 11 |

| Surgical margin status, n | |

| R0 | 138 |

| R1 | 50 |

| R2 | 7 |

| Lymph node metastasis, n | |

| Negative | 50 |

| Positive | 145 |

| Extrapancreatic neural invasion, n | |

| Positive | 108 |

| Negative | 87 |

| Portal invasion, n | |

| Positive | 63 |

| Negative | 132 |

| UICC stage, n | |

| IA | 9 |

| IB | 1 |

| IIA | 38 |

| IIB | 110 |

| III | 9 |

| IV | 28 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, n | |

| GEM | 142 |

| S1 | 6 |

| GEM+S1 or others | 2 |

| None | 45 |

| Time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (mean days) | 54.9 |

The median observational period for all patients was 595 d. The median survival was 27.1 mo, and the 5-year actuarial survival rate was 34.5%.

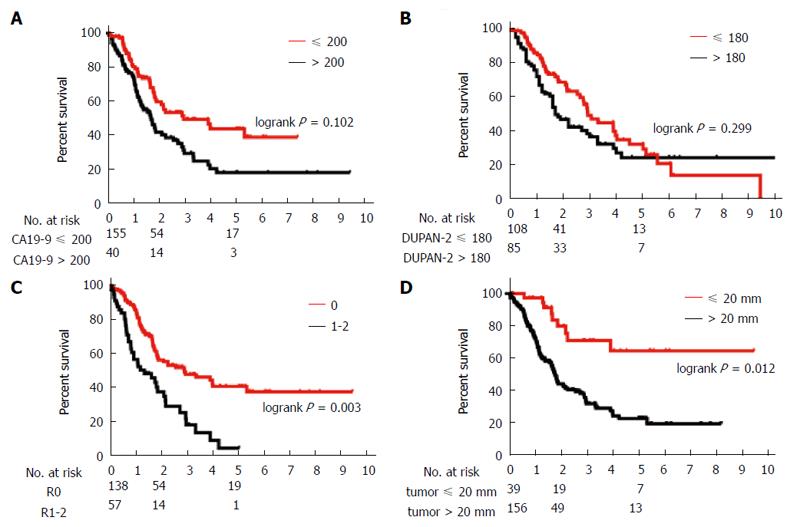

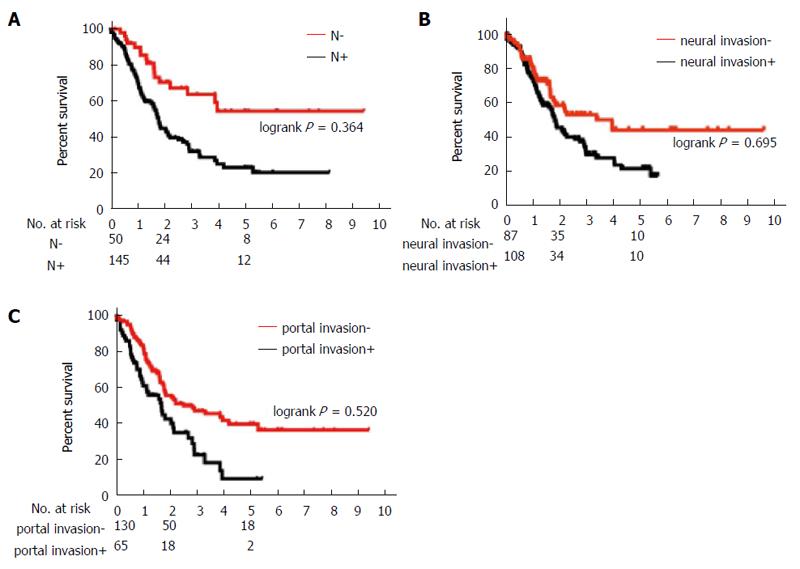

Table 2 shows the prognostic factors analyzed. The univariate analysis showed that UICC stage, CA19-9 ≤ 200 U/mL, DUPAN-2 ≤ 180 U/mL, tumor size ≤ 20 mm, R0 resection, absence of lymph node metastasis, absence of extrapancreatic neural invasion, and absence of portal invasion were all associated with a greater overall survival. Table 3 and Figures 1 and 2 show the results of from the multivariate analysis. Tumor size ≤ 20 mm (HR = 0.40; 95%CI: 0.17-0.83) and R0 resection (HR = 0.48; 95%CI: 0.30-0.77) were the only independent favorable prognostic factors.

| Variables | n | MST (mo) | 5-yr survival (%) | P value |

| Age | 0.071 | |||

| > 65 | 130 | 22.1 | 31.3 | |

| ≤ 65 | 65 | 47.3 | 40.5 | |

| Gender | 0.060 | |||

| Male | 108 | 17.5 | 31.6 | |

| Female | 87 | 23.9 | 38.6 | |

| CEA (ng/mL) | 0.082 | |||

| > 5 | 42 | 18.5 | 33.1 | |

| ≤ 5 | 138 | 35.2 | 38.4 | |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 0.006b | |||

| > 200 | 80 | 20.7 | 22.6 | |

| ≤ 200 | 104 | 47.4 | 47.2 | |

| DUPAN-2 (U/mL) | 0.003b | |||

| > 180 | 69 | 24.2 | 22.7 | |

| ≤ 180 | 101 | 30.8 | 51.0 | |

| Tumor size | < 0.001b | |||

| > 20 mm | 156 | 21.7 | 25.9 | |

| ≤ 20 mm | 39 | 29.4 | 69.9 | |

| Surgical margin status | < 0.001b | |||

| R0 | 138 | 47.3 | 45.2 | |

| R1-2 | 57 | 16.0 | 5.6 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | < 0.001b | |||

| Positive | 145 | 21.8 | 26.4 | |

| Negative | 50 | 28.8 | 55.8 | |

| Extrapancreatic neural invasion | 0.00b | |||

| Positive | 108 | 22.0 | 23.9 | |

| Negative | 87 | 47.4 | 47.9 | |

| Portal invasion | 0.006b | |||

| Positive | 63 | 21.1 | 15.0 | |

| Negative | 132 | 35.4 | 42.7 | |

| UICC Stage | < 0.001b | |||

| IA | 9 | 34.9 | 87.5 | |

| IB | 1 | 27.1 | 0 | |

| IIA | 38 | 28.2 | 51.3 | |

| IIB | 110 | 20.2 | 29.0 | |

| III | 9 | 16.3 | 0 | |

| IV | 28 | 10.4 | 14.4 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.301 | |||

| Yes | 150 | 21.1 | 40.5 | |

| No | 45 | 27.1 | 32.5 | |

| Time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.985 | |||

| > 40 d | 66 | 27.1 | 31.1 | |

| ≤ 40 d | 84 | 30.8 | 34.0 |

| Variables | HR | 95%CI | P value |

| CA19-9 ( ≤ 200) | 0.668 | 0.410-1.084 | 0.102 |

| DUPAN-2 ( ≤ 180) | 0.767 | 0.461-1.264 | 0.299 |

| Negative surgical margin (R0) | 0.478 | 0.296-0.770 | 0.003 |

| Tumor size ≤ 20 mm | 0.399 | 0.171-0.825 | 0.012 |

| No lymph node metastasis | 0.764 | 0.413-1.355 | 0.364 |

| No extrapancreatic neural invasion | 0.906 | 0.548-1.477 | 0.695 |

| No portal invasion | 0.859 | 0.541-1.370 | 0.520 |

Table 4 compares the 20 patients who survived ≥ 5-year and the 76 patients who died within 5 years after surgery. Comparison of these two groups showed that lower concentrations of DUPAN-2, tumor size ≤ 20 mm, R0 resection, absence of lymph node metastases and portal invasion were significantly associated with 5-year survival. Even among the 20 patients who survived ≥ 5-years, 13 (65%) had tumors > 20 mm, eight (40%) had lymph node metastases, 10 (50%) had extrapancreatic invasion, and two (10%) had portal invasion.

| Variables | 5-yr survivors(n = 20) | Non-survivors(n = 76) | P value |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 65.5 ± 9.4 | 67.2 ± 7.9 | 0.393 |

| Gender | 0.398 | ||

| Male | 10 | 46 | |

| Female | 10 | 30 | |

| Tumor marker, median (IQR) | |||

| CEA (ng/mL) | 2.0 (1.3-2.7) | 3.0 (1.6-5.4) | 0.536 |

| CA19-9 (U/mL) | 57.0 (35.0-378.0) | 213.5 (48.0-594.5) | 0.071 |

| DUPAN-2 (U/mL) | 79.5 (25.0-508.0) | 312.5 (55.8-965.3) | 0.032a |

| Tumor size | 0.008a | ||

| > 20 mm, n | 13 | 70 | |

| ≤ 20 mm, n | 7 | 6 | |

| UICC T classification | 0.161 | ||

| T1, n | 1 | 1 | |

| T2, n | 0 | 3 | |

| T3, n | 19 | 66 | |

| T4, n | 0 | 6 | |

| Surgical margin status | 0.004a | ||

| R0, n | 19 | 46 | |

| R1, n | 1 | 26 | |

| R2, n | 0 | 4 | |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.036a | ||

| Positive, n | 8 | 62 | |

| Negative, n | 12 | 14 | |

| Extrapancreatic neural invasion | 0.200 | ||

| Positive | 10 | 50 | |

| Negative | 10 | 26 | |

| Portal invasion | 0.005a | ||

| Positive | 2 | 31 | |

| Negative | 18 | 45 | |

| UICC stage | 0.184 | ||

| IA, n | 1 | 1 | |

| IB, n | 0 | 1 | |

| IIA, n | 7 | 11 | |

| IIB, n | 10 | 43 | |

| III, n | 0 | 4 | |

| IV, n | 2 | 16 | |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 0.707 | ||

| Yes | 15 | 60 | |

| No | 5 | 16 | |

| Time to initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (d) | 36.0 ± 24.0 | 64.5 ± 83.1 | 0.107 |

This study retrospectively analyzed patients who underwent resection for pancreatic cancer at a single center. An analysis of factors prognostic for survival showed that tumor size ≤ 20 mm and R0 resection were independently associated with long-term survival, indicating that early tumor detection and histologically curative resection were important to achieve long-term survival. A comparison of 5-year survivors with non-survivors revealed that a significantly higher percentage of survivors had low DUPAN-2 concentrations, tumor sizes ≤ 2 cm, negative surgical margins, no lymph node metastasis, and no portal invasion. Among the 20 patients who survived ≥ 5-years, 13 had tumors larger than 20 mm; eight patients had lymph node metastases; 10 patients had extrapancreatic neural invasion; and two patients had portal invasion. An analysis of the 19 patients who survived more than 3 years revealed that seven patients (36.8%) had lymph node metastasis and 16 patients (84.2%) had tumors larger than 20 mm[14]. Thus, even in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, radical resection can increase the long-term survival.

Several studies have also shown that surgical margin status and/or tumor size was associated with survival rate[5,6,10,14,15]. For example, a retrospective study of 194 pancreatic cancer patients found that negative surgical margin was the sole independent postoperative prognostic factor[10]. A more detailed evaluation of the histological margin status of the specimens found that tumors > 1.5 mm from the closest margin were significantly associated with longer survival[15]. Furthermore, analyses of 396[5] and 185[16] patients with pancreatic cancer showed that tumor size ≤ 2 cm was a significant prognostic factor. Collectively, these findings indicate that earlier detection and histologically curative resection can achieve longer survivals in pancreatic cancer patients.

The procedure required for histologically curative resection remains unclear. The methods suggested include “regional pancreatectomy”, i.e., extended pancreatic resection together with vascular resection and retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. The rationale for an extended operation is based on the high rates of intra- and extrapancreatic neural invasion and lymph node metastasis. An extended operation is thought to be essential for histologically curative resection[14]. Moreover, a study of 74 patients with pancreatic cancer found that the survival rate was significantly higher in patients who underwent an extended than a standard operation[17]. However, many recent prospective studies have shown that extended operations tend to increase morbidity and mortality rates without having a survival benefit[18-20]. A systematic review and meta-analysis showed no significant differences in the survival rate between standard and extended operations, with a trend towards increased morbidity in patients undergoing extended operations[21]. Indeed, a review of 424 patients in four prospective randomized controlled trials found that extended operation was not associated with a survival benefit but tended to increase the rates of postoperative morbidity, such as diarrhea, in the early months after surgery[22]. Thus, because a standard operation results in longer survival and avoids postoperative morbidity, extended operations are not performed at our facility.

The necessity and efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer also remains unclear. A multicenter, randomized, controlled phase III trial found that postoperative gemcitabine increased survival compared with observation alone[23]. Since then, gemcitabine has been the standard adjuvant chemotherapy for pancreatic cancer (also in Japan)[24]. Of our 195 patients, 150 patients (76.9%) received chemotherapy after operation. However, we were unable to show that either adjuvant chemotherapy or its early initiation significantly enhanced patient survival. A previous report indicated that survival was also significantly longer in patients who started adjuvant chemotherapy within 20 d after surgery than those patients who started chemotherapy more than 20 d after the operation[25], indicating that earlier initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy may contribute to a longer survival. In our study, 142 patients received gemcitabine and only six patients received S1; therefore, we were not able to compare survival in these two groups. Future assessments of the efficacy of S1 require a greater number of patients receiving this agent.

This study was limited by its retrospective design; its performance at a single center; and the small number of patients. Therefore, a large-scale multicenter study should be planned to confirm our findings.

We found that the combination of negative surgical margins and tumor size ≤ 20 mm independently reduced the mortality rate to less than half, indicating that earlier tumor detection and histologically curative resection are important factors contributing to long-term survival.

The prognosis of patients with pancreatic cancer remains quite poor, and surgery remains the only curative treatment for pancreatic cancer. However, the 5-year survival rate after surgery has been reported to be less than 25%. This study was designed to analyze the factors prognostic of survival in pancreatic cancer patients and the characteristics of long-term survivors.

Several studies have reported prognostic factors after surgical resection of pancreatic cancer. This research aims to determine which factors are associated with long-term survival, i.e., tumor size, lymph node metastasis, surgical margin status, tumor markers, and adjuvant chemotherapy, to improve the prognosis of pancreatic cancer patients.

In previous reports, the 5-year survival rate after surgery was less than 25%. The 5-year actuarial survival rate in the present study was 34.5%, and this rate is much higher than other reports. The Japan Pancreas Society (JPS) classification of pancreatic cancer includes many pathological factors that make it possible to perform a detailed study. In the present study, we performed further analyses about extraneural invasion and portal invasion according to the JPS classification.

The outcome of our study indicates that surgeons should make every effort to detect pancreatic cancer in an early stage and to perform histologically curative resection during surgery.

Adjuvant chemotherapy is chemotherapy used after a curative operation to prevent recurrence or metastasis.

This is a retrospective clinical investigation providing interesting information on the experience of a single center with pancreatic surgery outcomes. The study does not provide any new data but contributes additional data on a subject with significant available amount of data.

P- Reviewer: Mura B, Teramoto-Matsubara OT, Voutsadakis IA, Zhou L S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10002] [Cited by in RCA: 10453] [Article Influence: 696.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Reber HA, Gloor B. Radical pancreatectomy. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1998;7:157-163. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Begg CB, Cramer LD, Hoskins WJ, Brennan MF. Impact of hospital volume on operative mortality for major cancer surgery. JAMA. 1998;280:1747-1751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1241] [Cited by in RCA: 1276] [Article Influence: 47.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sohn TA, Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Koniaris L, Kaushal S, Abrams RA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, Hruban RH, Lillemoe KD. Resected adenocarcinoma of the pancreas-616 patients: results, outcomes, and prognostic indicators. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:567-579. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Lim JE, Chien MW, Earle CC. Prognostic factors following curative resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a population-based, linked database analysis of 396 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;237:74-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee SR, Kim HO, Son BH, Yoo CH, Shin JH. Prognostic factors associated with long-term survival and recurrence in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:358-362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Riediger H, Keck T, Wellner U, zur Hausen A, Adam U, Hopt UT, Makowiec F. The lymph node ratio is the strongest prognostic factor after resection of pancreatic cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1337-1344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 267] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wentz SC, Zhao ZG, Shyr Y, Shi CJ, Merchant NB, Washington K, Xia F, Chakravarthy AB. Lymph node ratio and preoperative CA 19-9 levels predict overall survival and recurrence-free survival in patients with resected pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;4:207-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Chatterjee D, Katz MH, Rashid A, Wang H, Iuga AC, Varadhachary GR, Wolff RA, Lee JE, Pisters PW, Crane CH. Perineural and intraneural invasion in posttherapy pancreaticoduodenectomy specimens predicts poor prognosis in patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:409-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Richter A, Niedergethmann M, Sturm JW, Lorenz D, Post S, Trede M. Long-term results of partial pancreaticoduodenectomy for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreatic head: 25-year experience. World J Surg. 2003;27:324-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 310] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Imamura M, Doi R, Imaizumi T, Funakoshi A, Wakasugi H, Sunamura M, Ogata Y, Hishinuma S, Asano T, Aikou T. A randomized multicenter trial comparing resection and radiochemotherapy for resectable locally invasive pancreatic cancer. Surgery. 2004;136:1003-1011. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Japan Pancreas Society. Classification of pancreatic carcinoma.sixth ed. Tokyo: Kanehara 2009; . |

| 13. | International Union Against Cancer. TNM classification of malignant tumors. sixth ed. New York: Weily-Liss 2002; . |

| 14. | Nagakawa T, Sanada H, Inagaki M, Sugama J, Ueno K, Konishi I, Ohta T, Kayahara M, Kitagawa H. Long-term survivors after resection of carcinoma of the head of the pancreas: significance of histologically curative resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jamieson NB, Chan NI, Foulis AK, Dickson EJ, McKay CJ, Carter CR. The prognostic influence of resection margin clearance following pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;17:511-521. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nitecki SS, Sarr MG, Colby TV, van Heerden JA. Long-term survival after resection for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Is it really improving? Ann Surg. 1995;221:59-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Manabe T, Ohshio G, Baba N, Miyashita T, Asano N, Tamura K, Yamaki K, Nonaka A, Tobe T. Radical pancreatectomy for ductal cell carcinoma of the head of the pancreas. Cancer. 1989;64:1132-1137. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: comparison of morbidity and mortality and short-term outcome. Ann Surg. 1999;229:613-622; discussion 622-624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 293] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pedrazzoli S, DiCarlo V, Dionigi R, Mosca F, Pederzoli P, Pasquali C, Klöppel G, Dhaene K, Michelassi F. Standard versus extended lymphadenectomy associated with pancreatoduodenectomy in the surgical treatment of adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: a multicenter, prospective, randomized study. Lymphadenectomy Study Group. Ann Surg. 1998;228:508-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 570] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Reddy SK, Tyler DS, Pappas TN, Clary BM. Extended resection for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Oncologist. 2007;12:654-663. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Michalski CW, Kleeff J, Wente MN, Diener MK, Büchler MW, Friess H. Systematic review and meta-analysis of standard and extended lymphadenectomy in pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:265-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Farnell MB, Aranha GV, Nimura Y, Michelassi F. The role of extended lymphadenectomy for adenocarcinoma of the head of the pancreas: strength of the evidence. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Oettle H, Post S, Neuhaus P, Gellert K, Langrehr J, Ridwelski K, Schramm H, Fahlke J, Zuelke C, Burkart C. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine vs observation in patients undergoing curative-intent resection of pancreatic cancer: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:267-277. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Ueno H, Kosuge T, Matsuyama Y, Yamamoto J, Nakao A, Egawa S, Doi R, Monden M, Hatori T, Tanaka M. A randomised phase III trial comparing gemcitabine with surgery-only in patients with resected pancreatic cancer: Japanese Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Pancreatic Cancer. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:908-915. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Kondo N, Nakagawa N, Sasaki H, Sueda T. Early initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy improves survival of patients with pancreatic carcinoma after surgical resection. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:419-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |