Published online Mar 7, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2420

Revised: November 27, 2013

Accepted: January 2, 2014

Published online: March 7, 2014

Processing time: 178 Days and 14.7 Hours

Peliosis hepatis (PH) is a vascular lesion of the liver that mimics a hepatic tumor. PH is often associated with underlying conditions, such as chronic infection and tumor malignancies, or with the use of anabolic steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and oral contraceptives. Most patients with PH are asymptomatic, but some present with abdominal distension and pain. In some cases, PH may induce intraperitoneal hemorrhage and portal hypertension. This study analyzed a 46-year-old male who received a transplanted kidney nine years prior and had undergone long-term immunosuppressive therapy following the renal transplantation. The patient experienced progressive abdominal distention and pain in the six months prior to this study. Initially, imaging studies revealed multiple liver tumor-like abnormalities, which were determined to be PH by pathological analysis. Because the hepatic lesions were progressively enlarged, the patient suffered from complications related to portal hypertension, such as intense ascites and esophageal varices bleeding. Although the patient was scheduled to undergo liver transplantation, he suffered hepatic failure and died prior to availability of a donor organ.

Core tip: Peliosis hepatis (PH) is a vascular lesion of the liver that mimics a hepatic tumor. PH has been associated with the use of anabolic steroids or immunosuppressive drugs. Although most patients remain asymptomatic, some patients suffer from PH-related portal hypertension complications. This case study describes a 46-year-old man who underwent long-term immunosuppressive therapy following renal transplantation. Upon development of abdominal distention, PH was diagnosed by pathological analysis. Ultimately, the patient suffered hepatic failure when the immunosuppressive agent was withdrawn and died.

- Citation: Yu CY, Chang LC, Chen LW, Lee TS, Chien RN, Hsieh MF, Chiang KC. Peliosis hepatis complicated by portal hypertension following renal transplantation. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(9): 2420-2425

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i9/2420.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i9.2420

Peliosis hepatis (PH) is a rare vascular lesion of the liver, characterized by cystic blood-filled cavities distributed throughout the parenchyma of liver. The term originates from the Greek word “pelios”, which means blue/black or discolored extravasated blood. Peliosis is most commonly found in the liver, but can also involve the spleen, pancreas, lungs, and other organs[1,2]. The epidemiology of PH is poorly characterized, in part because PH is often only identified as an incidental finding on abdominal imaging or via autopsy[3]. The pathogenesis of PH includes sinusoidal cell proliferation, which obstructs blood flow and causes pre-sinusoidal portal hypertension[4]. PH has also been described in patients with hematologic malignancies, infection with pulmonary tuberculosis, and human immunodeficiency virus infection, as well as those taking anabolic steroids, immunosuppressive drugs, and oral contraceptives[3,5-13]. Although most patients remain asymptomatic or have slowly progressive disease, some patients develop PH-related portal hypertension complications, such as esophageal variceal bleeding or intense ascites[14,15]. Here, we describe the case of a 46-year-old male renal transplant recipient with PH-related complications.

A 46-year-old male received a transplanted kidney for end-stage renal disease nine years prior to this study, after which he received long-term immunosuppressive therapy [mycophenolate mofetil (180 mg/tab twice a day), tacrolimus (1 mg/tab three times a day), and prednisolone (5 mg/tab daily)] to prevent renal graft rejection. The patient had a history of alcohol consumption (consumed five or more beverages per day) and smoking for thirty years, but had no family history of renal disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or liver malignancy. The patient presented to the emergency department with complaint of pain in the upper right quadrant of his abdomen, which he described as dull, radiating to the back, and persisting for several hours. The pain was unrelated to food intake or a change in posture, and there were no aggravating or relieving factors. The associated symptoms were nausea and vomiting. The patient did not report any fever, night sweating, jaundice, diarrhea, tarry stool, or body weight loss.

While in the emergency room, the following vital signs were recorded: the patient’s blood pressure was 140/80 mmHg, pulse rate was 113 beats per minute, respiratory rate was 20 breaths per minute, and body temperature 37.3 °C. A physical examination revealed no abnormalities outside of the abdominal area, where distended abdomen and hypoactive bowel sounds were observed. The right side of the abdomen was tender and the dull pain shifted upon abdominal percussion. The liver span was 16 cm in the right midclavicular line, and the spleen was not palpable. In addition, a superficial engorged vein was found on the abdominal wall. The patient’s laboratory data showed abnormal liver biochemistry tests, including: aspartate aminotransferase: 62 U/L, alanine aminotransferase: 108 U/L, total bilirubin: 1.4 mg/dL, and creatinine: 3.89 mg/dL. The patient had normocytic anemia (hemoglobin: 11.2 g/dL), normal platelet count (238000/mm3), and normal prothrombin time.

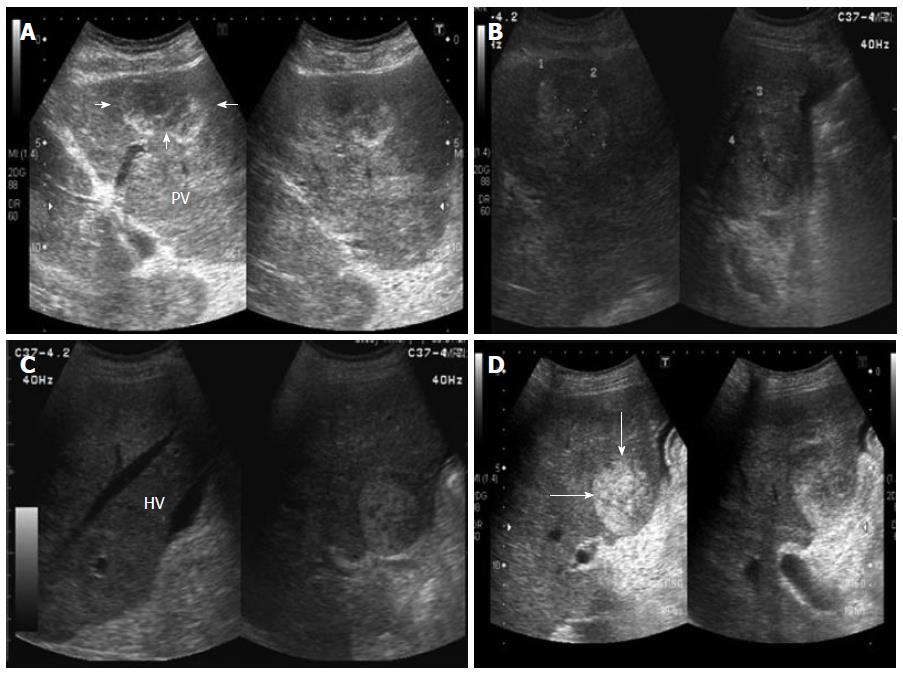

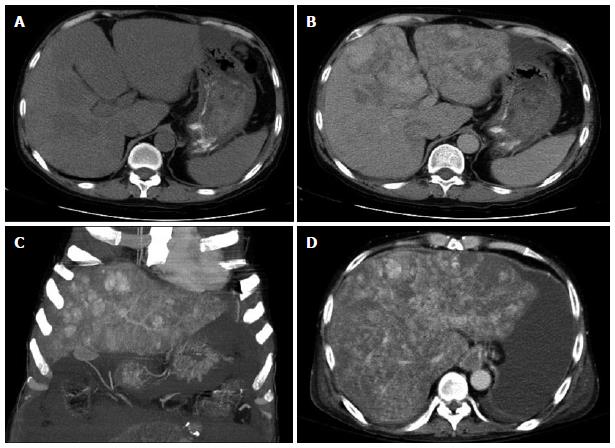

An abdominal ultrasound revealed multiple hyperechoic or mixed echoic tumors in the bilateral lobes of the liver (Figure 1); minimal ascites fluid was detected. Liver dynamic computed tomography (CT) also indicated the presence of multiple liver tumors. The liver tumors were hypodense before contrast injection (Figure 2A) and showed heterogeneous enhancement in the arterial phase and portal venous phase after contrast injection (Figure 2B). The liver tumor showed no sign of contrast washout in the delayed phase of CT. The patient continued to suffer from persistent abdominal pain and abdominal distension during hospitalization. An ultrasound-guided fine needle biopsy was performed on the tumors in liver segment four, where no ascites accumulated between the peritoneum and liver border. However, only fragmented hepatic tissue specimens and a large amount of blood fluid were obtained from the procedure.

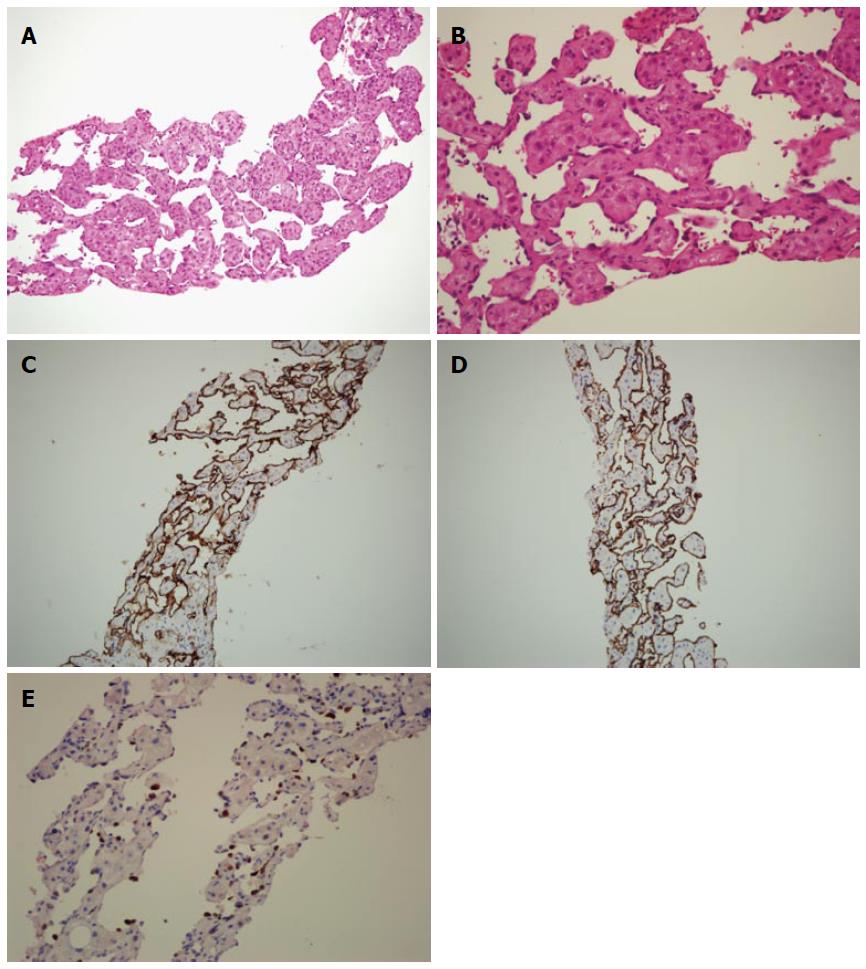

The ascites fluid that was aspirated from the lower abdomen was yellowish and clear. The serum ascites albumin gradient exceeded 1.1 mg/dL, indicating portal hypertensive type ascites. Histological analysis of the liver biopsy and cell block cytology specimens revealed no malignancies. Microscopic analysis of the liver biopsy specimens revealed sinusoidal dilatation with red blood cells and endothelial cells within the sinusoidal cavity (Figure 3A, B). Additional immunohistochemical analysis of biopsy specimens revealed that the sinusoidal endothelial cells were diffusely positive for CD34 and CD31 (Figure 3C, D). The biopsy specimens showed positive staining for Ki-67, a RNA transcription factor and nuclear protein selectively expressed in proliferating cells, which is used to measure cell proliferation within the tissue. The cell proliferative Ki-67 stain index was within 20% to 40%, suggesting active cell proliferation (Figure 3E).

The differential diagnoses from these pathologic findings included infection, hemangioma, and PH. Bacterial and viral infections were excluded based on the negative results of bacterial culture and serum antibody studies for the Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and human immunodeficiency virus. The rapidly increasing size of the tumor was not consistent with hemangioma, thus this diagnosis was also excluded. Due to the exclusion of these alternatives and the clinical presentation of the lesion, PH was the most likely diagnosis. The patient suffered from portal hypertension-related complications, including massive ascites (Figure 2C, D) and recurrent bleeding esophageal varices. Although the patient was scheduled to undergo a liver transplantation, the variceal bleeding, intense ascites, and hepatic encephalopathy led to death prior to availability of a donor organ.

In the renal transplant setting, PH can occur after transplantation, rather than being a manifestation of chronic kidney disease[11]. Possible causes of PH development post-transplantation include the use of immunosuppressive drugs, such as azathioprine and cyclosporine, or the development of an opportunistic infection[11,13,16]. For example, PH incidence can be reduced by administration of sulphonamide therapy to prevent Pneumocystis carinii infection[17]. Some drugs known to cause PH, including 6-thioguanine, oxaliplatin and urethane, can induce sinusoidal endothelial cell damage, consistent with the pathology of the patient described herein. However, other drugs associated with PH, such as anabolic steroids, glucocorticoids, methotrexate, vitamin A and oral contraceptives, do not affect sinusoidal endothelial cells.

The risk factors for the patient in this study may have been related to his post-renal transplantation status and long-term use of immunosuppressive agents. However, there are no current reports associating mycophenolate mofetil or tacrolimus with sinusoidal endothelial cell damage. Another PH risk factor for this patient was alcohol consumption, which can contribute to glutathione depletion. Sinusoidal endothelial damage has been associated with glutathione depletion[13], and glutathione levels play an essential role for immunosuppressant detoxification in sinusoidal endothelial cells. Thus, given the patient’s alcohol consumption and the use of several immunosuppressive drugs, glutathione depletion was a major risk factor for hepatic sinusoidal endothelial damage.

Lesions of PH are often asymptomatic or associated with abnormal liver biochemical test levels, but more severe complications exist, such as progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension[3,7-9,16,18,19]. Hepatic lesions may regress upon withdrawal of immunosuppressive drugs, but this approach substantially increases the risk of transplant rejection[3]. As a result, this strategy has not been adequately evaluated. In this specific patient, immunosuppressive therapy could not be discontinued because of the risk of renal graft failure, thus increasing the risk of hepatic lesions.

By dynamic CT imaging, PH typically presents with hypoattenuating lesions before contrast injection, but with variable enhancement patterns after contrast injection. In the arterial phase, the lesions may present with progressive enhancement in the centrifugal or centripetal direction. In the delayed phase, the lesion may show a diffuse, increased attenuation. The differential diagnoses for these lesions include abscesses, hemangiomas, and hypervascular metastases[20]. Pyogenic hepatic abscesses appear as a low-density lesion with peripheral enhancing after contrast injection. Some septa, pyogenic fluid, or gas within the lesion are also seen. It is important to distinguish a hepatic abscess from PH and to avoid inadvertent aspiration of the periotic lesions, which may be fatal[19].

Two histologic types of PH have been reported, a parenchymal type and a phlebectatic type. The parenchymal type is characterized by hemorrhagic parenchymal necrosis and congestion of the lining of cavities with hepatocytes. The phlebectatic type is characterized by endothelial cells lining the cavity and aneurysmal dilation of the central vein[4]. In our patient, the pathological analysis of the liver biopsy specimen revealed dilated sinusoidal space with red blood cells and endothelial lining cells in the sinusoidal cavity, consistent with the phlebectatic form of PH. Increased cell proliferation, as indicated by Ki-67 staining, was detected in our patient. Because there are no previous reports that have analyzed the Ki-67 index in a case of PH, the diagnosis of well-differentiated angiosarcoma cannot be completely excluded for our case given the status of cellular hyperproliferation.

The treatment of PH varies between individuals. Serial follow-up imaging studies may be adequate for asymptomatic patients with slow progressive disease. Furthermore, removing exacerbating factors, such as certain drugs or infection, may halt the progression of PH. For patients with localized lesions, a hepatectomy can be performed to remove the lesions[6,9,10,12,21]. For patients with rapidly progressing PH and additional complications, liver transplantation may be the optimal therapeutic option[22].

In conclusion, PH is a rare vascular lesion of the liver in patients receiving kidney transplantation and is mainly associated with prolonged use of certain immunosuppressants. Patients with PH are often asymptomatic, but may develop progressive fibrosis, cirrhosis, and portal hypertension. Hepatic failure can develop if immunosuppressive therapy cannot be withdrawn, which likely contributed to the outcome of the specific case described herein.

The abdominal distension and pain were the main symptoms in the case.

Diagnosis is suspected with imaging techniques and assessed by liver biopsy.

The differential diagnoses for these lesions include abscesses, hemangiomas, hypervascular metastases and angiosarcoma and all of them can be distinguished by clinical conditions and CT images but except angiosarcoma.

Abnormal liver biochemical test levels can be the initial presentation but the thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia and hyperbilirubinemia can be founded when portal hypertension and hepatic failure develop.

By dynamic computed tomography imaging, peliosis hepatis (PH) typically presents with hypoattenuating lesions before contrast injection, but with variable enhancement patterns after contrast injection. In the arterial phase, the lesions may present with progressive enhancement in the centrifugal or centripetal direction. In the delayed phase, the lesion may show a diffuse, increased attenuation.

Microscopic analysis of the liver biopsy specimens revealed sinusoidal dilatation with red blood cells and endothelial cells within the sinusoidal cavity.

Removing exacerbating factors, such as certain drugs or infection, may halt the progression of PH and for patients with localized lesions, a hepatectomy can be performed to remove the lesions.

The term “peliosis” originates from the Greek word "pelios", which means blue/black or discolored extravasated blood.

The peliosis hepatis was founded in patient with specialized risk factors and it may go to hepatic failure even to death.

Hepatic peliosis is a rare condition mimicking hepatic tumors. The natural history of this disease is variable with little knowledge in the literature. Therefore, the case is interesting. The references have been updated.

P- Reviewers: Bordas JM, Velayos B S- Editor: Cui XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Fowell AJ, Mazhar D, Shaw AS, Griffiths WJ. Education and imaging. Hepatobiliary and pancreatic: peliosis hepatis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:1082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Makdisi WJ, Cherian R, Vanveldhuizen PJ, Talley RL, Stark SP, Dixon AY. Fatal peliosis of the liver and spleen in a patient with agnogenic myeloid metaplasia treated with danazol. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:317-318. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Asano S, Wakasa H, Kaise S, Nishimaki T, Kasukawa R. Peliosis hepatis. Report of two autopsy cases with a review of literature. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1982;32:861-877. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tsokos M, Erbersdobler A. Pathology of peliosis. Forensic Sci Int. 2005;149:25-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kim SH, Lee JM, Kim WH, Han JK, Lee JY, Choi BI. Focal peliosis hepatis as a mimicker of hepatic tumors: radiological-pathological correlation. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2007;31:79-85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Testa G, Panaro F, Sankary H, Chejfec G, Mohanty S, Benedetti E, Layden T. Peliosis hepatis in a living related liver transplantation donor candidate. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21:1075-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Iannaccone R, Federle MP, Brancatelli G, Matsui O, Fishman EK, Narra VR, Grazioli L, McCarthy SM, Piacentini F, Maruzzelli L. Peliosis hepatis: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W43-W52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Corpa MV, Bacchi MM, Bacchi CE, Coelho KI. Peliosis hepatis associated with lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma: an autopsy case report. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:1283-1285. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Staub PG, Leibowitz CB. Peliosis hepatis associated with oral contraceptive use. Australas Radiol. 1996;40:172-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Omori H, Asahi H, Irinoda T, Takahashi M, Kato K, Saito K. Peliosis hepatis during postpartum period: successful embolization of hepatic artery. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:168-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cavalcanti R, Pol S, Carnot F, Campos H, Degott C, Driss F, Legendre C, Kreis H. Impact and evolution of peliosis hepatis in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1994;58:315-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tappero JW, Mohle-Boetani J, Koehler JE, Swaminathan B, Berger TG, LeBoit PE, Smith LL, Wenger JD, Pinner RW, Kemper CA. The epidemiology of bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis. JAMA. 1993;269:770-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Elsing C, Placke J, Herrmann T. Alcohol binging causes peliosis hepatis during azathioprine therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:4646-4648. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Berzigotti A, Magalotti D, Zappoli P, Rossi C, Callea F, Zoli M. Peliosis hepatis as an early histological finding in idiopathic portal hypertension: A case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3612-3615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jacquemin E, Pariente D, Fabre M, Huault G, Valayer J, Bernard O. Peliosis hepatis with initial presentation as acute hepatic failure and intraperitoneal hemorrhage in children. J Hepatol. 1999;30:1146-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Izumi S, Nishiuchi M, Kameda Y, Nagano S, Fukunishi T, Kohro T, Shinji Y. Laparoscopic study of peliosis hepatis and nodular transformation of the liver before and after renal transplantation: natural history and aetiology in follow-up cases. J Hepatol. 1994;20:129-137. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Mohle-Boetani JC, Koehler JE, Berger TG, LeBoit PE, Kemper CA, Reingold AL, Plikaytis BD, Wenger JD, Tappero JW. Bacillary angiomatosis and bacillary peliosis in patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: clinical characteristics in a case-control study. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:794-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Fine KD, Solano M, Polter DE, Tillery GW. Malignant histiocytosis in a patient presenting with hepatic dysfunction and peliosis hepatis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:485-488. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Cohen GS, Ball DS, Boyd-Kranis R, Gembala RB, Wurzel J. Peliosis hepatis mimicking hepatic abscess: fatal outcome following percutaneous drainage. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1994;5:643-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Torabi M, Hosseinzadeh K, Federle MP. CT of nonneoplastic hepatic vascular and perfusion disorders. Radiographics. 2008;28:1967-1982. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Pan W, Hong HJ, Chen YL, Han SH, Zheng CY. Surgical treatment of a patient with peliosis hepatis: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2578-2582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hyodo M, Mogensen AM, Larsen PN, Wettergren A, Rasmussen A, Kirkegaard P, Yasuda Y, Nagai H. Idiopathic extensive peliosis hepatis treated with liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2004;11:371-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |