CASE REPORT

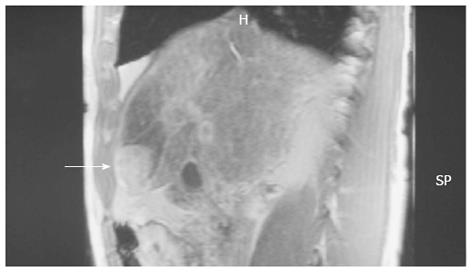

A 55-year-old man with a 6-year history of alcoholic cirrhosis diagnosis presented with marked elevation of alpha-fetoprotein (a-FP; 14000 ng/mL, reference range: 0-40 ng/mL) during his regular checkup. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a tumor-like lesion on segment 4 of the liver (Figure 1). The patient was admitted to the Department of Surgery for treatment on 1 April 2008. During the initial interview, the patient self-described a long-term history of large-quantity daily alcohol intake (10 L of wine/d for 10 years) and a short-term history of unknown quantity daily intake of SJW (for the last few months). Hepatomegaly was found upon physical examination, but further serologic analyses revealed normal levels of ferritin (120 g/L, reference range: 24-248 g/L) and ceruloplasmin (32 g/L, reference range: 20-50 g/L) and negative results for autoimmune markers and hepatitis B- and C-specific antigens.

Figure 1 Magnetic resonance imaging showed a tumor-like lesion (arrow) and ischemia in segment 4 of the liver.

Fine needle aspiration of the tumor performed on 2 April 2008 revealed normal and atypical hepatocytes, nodular regenerative atypia, and transitional and differentiated bile duct epithelial cells. In addition, three distinct hepatocyte aggregations were observed, which were characterized by pleomorphism, non-uniform nuclear size, increased nucleocytoplasmic ratio, diffuse chromatin distribution, and large, prominent nucleoli. While the presence of these aggregates suggested a neoplastic character for the tumor-like lesion, atypia could not be excluded due to the presence of the regenerative nodules and cirrhotic features.

The patient underwent segment 4 resection on 4 April 2008. The procedure was modified perioperatively to a limited wedge resection with ethanol injection of the cut liver surface according to the observations of substantial ischemia in the left liver lobe, gross pathological features of cirrhosis in the right lobe, and presence of three small (about 2 mm each) satellite nodules. The resected specimen measured 3 cm × 2.5 cm × 1.5 cm. Sectioning revealed multiple white nodules throughout the tumor tissue, which itself was surrounded by normal liver tissue with a micro-nodular cirrhotic appearance.

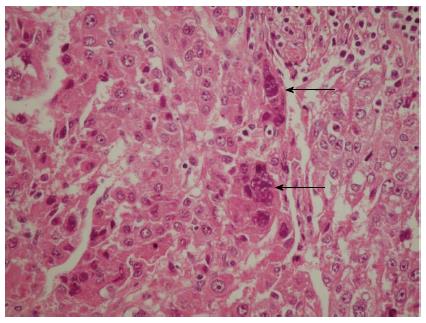

Subsequent microscopic analysis of the nodules revealed disordered architecture of the surrounding liver cell. The cells comprising the nodules showed pleomorphism and atypia, with some syncytial type multinuclear giant cells that had features similar to infantile giant cell hepatitis (Figure 2). Moreover, these giant cells also displayed the same nuclear atypia as the other HCC cells, which suggested that the cells were part of the tumor itself and not merely entrapped non-neoplastic cells; the marked lack of any giant cell changes in the adjacent liver tissue further reinforced this hypothesis.

Figure 2 Hematoxylin and eosin-staining of a representative hepatocellular carcinoma section showing the multinuclear giant syncytial cells (arrows).

A small number of mitotic figures, both typical and atypical and with or without apoptotic bodies, were observed in the tumor-like lesion, including the nodules, as well as beyond the lesion boundary, in the adjacent liver parenchyma. Inflammatory cells, such as lymphocytes and plasmatocytes, were present throughout the HCC and adjacent liver tissue, with greater incidence in the septa. Hyperplasia was observed in the marginal area of the nodules and small bile ducts. The adjacent liver parenchyma showed microvesicular steatosis, pericellular fibrosis, and moderate hemosiderin accumulation (grade 2, as determined by Prussian blue iron stain) in hepatocytes and Kupffer cells but no copper accumulation (as determined by orcein stain).

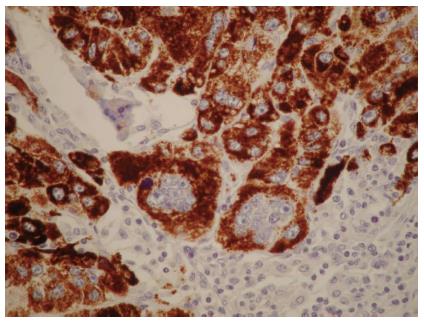

Immunohistochemical analysis showed hepatocyte antigen-positive staining for the neoplastic cells and SGCs (Figure 3). No cells showed immunoreactivity for macrophage-specific markers, such as CD68, but occasional cells showed immunoreactivity for the proliferation marker Ki-67/MIB-1 or the oncoprotein p53. The giant cells’ nuclei showed a remarkable lack of immunoreactivity for all of the markers detected.

Figure 3 Mononuclear and multinuclear carcinoma cells showed reactivity for the hepatocyte antigen (brown).

Magnification × 40.

According to the collective histological findings, the diagnosis was made for cirrhosis-related HCC with SGCs. Up to the last follow-up examination, performed on 10 April 2013, the patient had maintained a-FP levels within the normal range and showed no signs of tumor recurrence by liver imaging.

DISCUSSION

While adult cases of giant cell HCC are relatively common, and its clinical and histologic features are well characterized, the case of giant cell HCC presented herein highlights the unusual histological manifestation of syncytial type cells[1-5]. Previous case reports of these rare tumor types have demonstrated the mesenchymal and non-neoplastic nature of the giant cells, leading to the suggested nomenclature of liver cell carcinoma with osteoclast-like giant cells[4-6]. However, the giant cells of the current case showed an epithelial and hepatocyte-originated neoplasmic nature, leading to the diagnosis of HCC with syncytial giant cells.

Another distinctive feature of this HCC case is its manifestation in cirrhotic liver. While cirrhosis was a likely etiology of the HCC, as suggested by the presence of nodular cirrhosis and microvesicular steatosis, the etiology of the cirrhosis was not obvious, and could have been long-term alcoholism or hemosiderosis. The patient’s chronic consumption of SJW represents another potential complicating factor. The known hepatoxic properties of this herbal medicine may have contributed to or been the primary inducing factor of the syncytial phenotype of the giant cells.

The liver is among the first organs to experience toxic injury, as it is the main site of endo- and xenobiotic bio-transformation. As such, a primary focus of drug development and clinical trials is determining the liver-related side effects of pharmaceutical and herbal medicines. Among the most common liver injuries are acute liver necrosis, hepatitis, cholestasis, fibrosis and cirrhosis; in addition, many of the medicines show either direct or indirect carcinogenic potential. Over the past few decades, the traditional herbal preparation of SJW extract has risen tremendously in popularity in the Western world, largely due to its observed benefits in treating mild to moderate depression[7-9], and bladder cancer[10,11].

Recent studies have indicated a potential clinical benefit of SJW for treating alcoholism, and implicated the bioactive phytochemical hyperforin as the constituent responsible for this response[12]. Interestingly, hyperforin has also been shown to have anti-microbial activity against Gram-positive bacteria and numerous viruses[13,14]. Studies of the molecular mechanisms underlying the bioactive activities of hyperforin have revealed a complex functional interaction with the other SJW constituents of essential oils, phloroglucinols, and flavonoids to induce a photoactivation process, possibly leading to production of singlet oxygen molecules[13,14]. Photoactivated-free radicals may exert the protective anti-infective or anti-tumor effects-for the latter, possibly through activation of apoptosis-related pathways[15,16].

In general, SJW is well tolerated as both topical and oral preparations. The most commonly reported adverse effects are gastrointestinal-related (i.e., nausea, hypogastric pain, loss of appetite, diarrhea, gastric complaints[17] and sedative-related (i.e., dizziness, confusion, and fatigue)[18]. Rare cases of photosensitivity development have also been reported, most often associated with systemic administration[19], and possible fertility risks have been suggested by some studies as well[20].

Another unknown mechanism of SJW is its ability to interact, either beneficially or detrimentally, with conventional drugs concomitantly-administered[21]. This possibly was highlighted by the observation of SJW-associated enhancement of P-glycoprotein, an intestinal multidrug transporter, and the cytochrome P450 (CYP) oxidative enzyme superfamily members CYP3A4 and CYP2C9. The induction of CYP3A4 represents a particularly troubling (and unresolved) clinical concern because of its abundance in the liver and intestine, both important sites of drug bio-transformation[22]. In addition, high-dosage SJW has been shown to activate the detoxification pathway mediated by the pregnane X receptor (PXR), a particularly promiscuous receptor; PXR overstimulation is detrimental and may result from SJW interactions with other drugs[23]. Finally, the non-standardized compositions of SJW extract preparations, available as over-the-counter medicines and often taken without clinical oversight, further complicate our ability to understand the benefits and risks of SJW, such as which may have contributed to the current case[24].

Despite these unknown features of SJW bioactivity, the significant anti-tumor effects of hyperforin in cell culture and animal systems have prompted continued efforts to investigate its potential as an efficacious cancer therapy that is less toxic than the current chemo- and radio-therapies. For example, in vitro studies of various rat and human cancers (e.g., mammary carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, and lymphoma) showed equal or greater anti-tumor effects of hyperforin compared to the common cytostatic drugs camptothecin, paclitaxel, and vincristine[25]. Moreover, the molecular mechanism of hyperforin-mediated tumor cell apoptosis was shown to involve, at least partially, mitochondrial release of cytochrome c and caspase activation, thereby triggering cell death pathways[25,26]. However, as with any pharmacologic or herbal medicine, absolute anti-tumor activity is not guaranteed and inappropriate doses or concomitant drug administrations may create a pro-tumor situation.

For the case of cirrhosis-related HCC with SGCs described herein, we cannot conclude the role played by SJW with any certainty. The patient’s ingestion of SJW may have created a hepatotoxic condition that promoted the progression of cirrhosis or HCC. Nonetheless, this case highlights the need for further studies of SJW to determine its side effects profile and safe dosages under various physiologic and pathogenic conditions; such knowledge is particularly important as the manufacture (i.e., compositions) and use (i.e., dose, duration, and in conjunction with other drugs) of SJW is non-uniform and widespread.