Published online Feb 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1594

Revised: August 22, 2013

Accepted: September 4, 2013

Published online: February 14, 2014

Processing time: 264 Days and 7.5 Hours

AIM: To compare the efficacy and safety of recombinant streptokinase (rSK) and phenylephrine-based suppositories in acute hemorrhoidal disease.

METHODS: A multicenter (14 sites), randomized (1:1), open, parallel groups, active controlled trial was done. After inclusion, subjects with acute symptoms of hemorrhoids, who gave their written, informed consent to participate, were centrally randomized to receive, as outpatients, rSK (200000 IU) or 0.25% phenylephrine suppositories, which had different organoleptic characteristics. Treatment was administered by the rectal route, one unit every 6 h during 48 h for rSK, and up to a maximum of 5 d (20 suppositories) for phenylephrine. Evaluations were performed at 3, 5 and 10 d post-inclusion. The main end-point was the 5th-day complete clinical response (disappearance of pain and edema, and ≥ 70% reduction of the lesion size). Time to response and need for thrombectomy were secondary efficacy variables. Adverse events were evaluated too.

RESULTS: 5th day complete response rates were 83/110 (75.5%) and 36/110 (32.7%) with rSK and phenylephrine suppositories, respectively. This 42.7% difference (95%CI: 30.5-54.2) was highly significant (P < 0.001). The advantage was detected since the early 3rd day evaluation (37.3% vs 6.4% for the rSK and active control groups, respectively; P < 0.001) and was kept even at the late 10th day assessment (83.6% vs 58.2% for rSK and phenylephrine, respectively; P < 0.001). Time for complete response was significantly shorter (P = 0.031; log-rank test) in the rSK group (median: 4.9 d; 95%CI: 4.8-5.0) with respect to the active control (median: 9.8 d; 95%CI: 9.8-10.0). Thrombectomy was necessary in 1/59 and 8/57 patients with baseline thrombosis in the rSK and phenylephrine groups, respectively (P = 0.016). There were no adverse events attributable to the experimental treatment.

CONCLUSION: rSK suppositories showed a significant advantage over a widely used over-the-counter phenylephrine preparation for the treatment of acute hemorrhoidal illness, with an adequate safety profile.

Core tip: Medical treatments for acute hemorrhoidal disease come very seldom from randomized, controlled clinical trials. The paper describes that a candidate to a new therapeutic alternative, based on thrombolysis, shows significant efficacy advantage with respect to a widely used, over-the-counter, hemorrhoidal product.

-

Citation: Hernández-Bernal F, Castellanos-Sierra G, Valenzuela-Silva CM, Catasús-Álvarez KM, Valle-Cabrera R, Aguilera-Barreto A, Investigators PALSTT3GO. Recombinant streptokinase

vs phenylephrine-based suppositories in acute hemorrhoids, randomized, controlled trial (THERESA-3). World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(6): 1594-1601 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i6/1594.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i6.1594

Hemorrhoids are one of the principal reasons that patients seek consultation from a colon and rectal surgeon[1-3]. The exact incidence of this common condition is difficult to estimate, as many people are reluctant to seek medical advice for various personal, cultural, and socioeconomic reasons, but epidemiological studies report a prevalence varying from 4.4% in adults in the United States to over 30% in general practice in London[1,4,5].

Treatments include conservative medical management, office procedures, and surgical approaches in an operating room. The least-invasive approach should be considered given the physiologic importance of the hemorrhoid cushions and the potential self-limiting nature of many hemorrhoid symptoms. The decision on how to treat depends on many factors including the severity of the signs and symptoms and can change in patients with thrombosis, important prolapse or profuse hemorrhage, and other medical conditions[1-3].

The initial treatment of the hemorrhoidal illness consists of general conservative measures (hygienic-dietetic, life style changes, symptomatic treatment) to restore the intestinal habit and to diminish the local symptoms. Although several medicines have been tested, significant benefits have not been obtained to control this condition. When response is obtained the result takes many days[3,6]. Therefore, in an important group of patients surgery becomes the final solution[7,8]. In such cases, surgical or other invasive procedures are indicated (hemorrhoidectomy, ligation, sclerotherapy, infrared photoclotting, cryo and laser therapy), not exempted from complications[2-4,9-11].

Streptokinase (SK) is an indirect fibrinolytic agent that interacts with plasminogen, forming an active complex with protease action that activates plasminogen into plasmin. The efficacy of SK has been demonstrated in acute myocardial infarct[12,13] and in other thrombotic diseases[14]. The local application of recombinant SK (rSK) on hemorrhoids, where thrombosis and/or inflammation with microthrombi may be present was first tested in a proof-of-concept, pilot trial in 10 patients[15] and afterwards in a phase II, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 80 patients. A 200000 IU, but not a 100000 IU rSK suppository showed a beneficial effect on hemorrhoidal symptoms (36% larger response rate, 5 d faster), over excipient controls, with an adequate safety profile[16]. These were the first reports of a thrombolytic treatment for this condition.

Vasoconstrictors have been also used as non-invasive treatment of hemorrhoids[17]. Among them, phenylephrine is widely prescribed and there are over-the-counter products of this drug established in common medical practice since several decades. The aim of the present work was to compare the efficacy and safety of 200000 IU rSK suppositories vs a phenylephrine-based commercially available suppository for the treatment of acute hemorrhoids in terms of clinical response, need for thrombectomy, and adverse events through a multicenter, randomized clinical trial, as part of the clinical development of the experimental formulation.

A randomized (1:1), parallel groups, open, controlled, phase III clinical trial was carried out in 14 hospitals from 10 Cuban provinces. The National Center for the Coordination of Clinical Trials, Havana was outsourced as a contract research organization (CRO) for trial coordination and monitoring, product supply, and data collection. Patients, 18-75 years old, with acute symptoms and signs of hemorrhoids, characterized by anal pain, with tumors of variable size and appearance, maybe colored red-violet, usually associated with significant edema, who gave their written, informed consent to participate were eligible. Exclusion criteria were: SK administration in the previous 6 mo, antecedents of intracranial hemorrhage, allergy to SK, phenylephrine or any other component of the medicament, stroke, intracranial surgery or skull trauma less than 3 mo before, any other bleeding-risk condition, and history of severe arterial hypertension or ventricular tachycardia. Patients with acute diarrhea in the last 12 h, hemorrhoidal disease caused by portal hypertension, septic or severe hemorrhagic complications, associated fistula or cancer, pregnancy, puerperium, and mental disorders were also excluded. The trial was done in proctology wards from central hospitals in Havana or from province capitals throughout the country. Participant investigators were specialists in colo-proctology. The protocol followed the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committees of the participating hospitals and by the Cuban Regulatory Authority.

Recombinant streptokinase was produced in Escherichia coli at the Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (CIGB), Havana[18]. Suppositories, 2 g (Proctokinasa®, Heber Biotec, Havana), were prepared containing 200000 IU of rSK, 20 μg thimerosal, 20 mg sorbitan monostearate (Span 60), 10 mg sodium salicylate, and hard fat (Witepsol W25). Preparation H® suppositories (Wyeth, Richmond), contained 0.25% phenylephrine HCl, 85.39% cocoa butter, corn starch, methylparaben, propylparaben, and shark liver oil. Their organoleptic characteristics, presentations and therapeutic schedules were different, which determined that the trial could not be double-blind.

The patients included were randomly distributed to the treatment groups: (1) rSK; and (2) phenylephrine suppositories. Treatment was administered by the rectal route, one unit every 6 h during 48 h for rSK, and up to a maximum of 5 d (20 suppositories) as labeled for the phenylephrine commercial preparation. Concomitant treatment for all groups included high-fiber diet, abundant liquid ingestion, bed rest, local hygiene, and oral analgesics if pain. Thrombectomy was performed in cases with thrombosis if there was no improvement at all during the first 72 h and the patient’s pain required it. Treatment started immediately after confirmation of inclusion and continued as outpatient. Its compliance was monitored through a log card designed for that purpose, and recollection of the empty suppository blister packs.

Diagnosis was done clinically or verified by anoscopy, if necessary. Hemorrhoids were classified according to their origin. External hemorrhoids originate distal to the dentate line, arising from the inferior hemorrhoidal plexus. Internal hemorrhoids originate proximal to the dentate line, arising from the superior hemorrhoidal plexus, covered with mucosa. Internal hemorrhoids were further classified into four grades according to the extent of prolapse. Grade I: the hemorrhoidal tissue protrudes into the lumen of the anal canal, but does not prolapse outside; grade II: hemorrhoids may prolapse beyond the external sphincter and be visible during evacuation but spontaneously return to lie within the anal canal; grade III: hemorrhoids protrude outside the anal canal and require manual reduction, and grade IV: hemorrhoids are irreducible and are constantly prolapsed. Some hemorrhoids were regarded as mixed (internal-external), arising from the inferior and superior hemorrhoidal plexus and their anastomotic connections. Acute hemorrhoids could present with thrombosis or not[1-4,19].

Clinical evaluations were carried out by the specialists on the 3rd, 5th and 10th day outpatient visits after treatment onset. The main endpoint was the proportion of patients with complete clinical response on the 5th day, given by disappearance of pain and edema, and reduction of more than 70% of the initial lesion size (measured with calibrated millimeter rulers). Time to response and need for thrombectomy were secondary efficacy variables.

The adverse events (type, duration, severity, outcome, and causality relationship) were carefully registered. The severity of the adverse events was classified in three levels: (1) mild, if no therapy was necessary; (2) moderate, if a specific treatment was needed; and (3) severe, when hospitalization or its prolongation was required, the reaction was life-threatening or contributed to patient’s death. A qualitative assessment was used to classify the causal relationship as definite, probable, possible or doubtful[20]. Adverse reactions known for intravenous SK (fever, shivering, nausea, vomiting, low blood pressure, hemorrhages and allergy) were specially searched.

Central 1:1 randomization was done at CIGB, in blocks of 4 individuals, by means of a computerized random number generator. Each hospital pharmacy received a stock with both products, unmasked, in sufficient amounts to guarantee the treatment according to their inclusion rate. The decision to accept a participant was made by the investigators in ignorance of the group assignment. The informed consent was obtained and then the clinical researcher phoned (a 24-h line was specially set up for the trial) the central trial coordinator who, after collecting the patient’s initials, assigned the corresponding code (site code + patient consecutive number) and treatment, which was then prescribed and requested to the hospital pharmacy. Trial on-site monitoring verified this process as well as the accurateness of all the case report forms vs the primary information, treatment compliance, and all Good Clinical Practices procedures.

SK treatment duration was prolonged from 24 h in the previous trials[15,16] to 48 h since in those studies some patients had not achieved response but only showed some improvement at 24 h, so it was supposed that a longer treatment would yield a better result. At the same time the main response criteria was changed from 90% lesion size reduction to 70%, combined with pain disappearance, following expert criteria that considered that this reduction was enough for the patient to return to his/her usual activities.

The trial hypothesis was to obtain a proportion of 70% of the patients with complete response at the 5th day after treatment onset with rSK suppositories (as obtained in the previous studies) and a 20% advantage (that could be considered clinically significant) over the response rate in the active control group. Assuming types I and II errors of 0.05 and 0.10, respectively, in a superiority model, a sample size of 101 subjects was estimated using the PASS software (http://www.ncss.com). Considering 10% dropouts the final sample size was rounded to 110 subjects per group.

After review and query resolution, data were double-entered in databases built with the OpenClinica software (http://www.openclinica.com). SPSS version 15 software was used for statistical analyses. Complete response rates comparison between groups was assessed by the likelihood ratio χ2 test (or the Fisher’s exact test) and the 95% confidence interval (CI) of the estimated proportions and their differences. Times to complete response were estimated by survival analyses (Kaplan-Meier) and compared with the log-rank test. The level of significance chosen was α = 0.05. All analyses were done on intention-to-treat basis. Missing evaluations were imputed as the last observation carried forward.

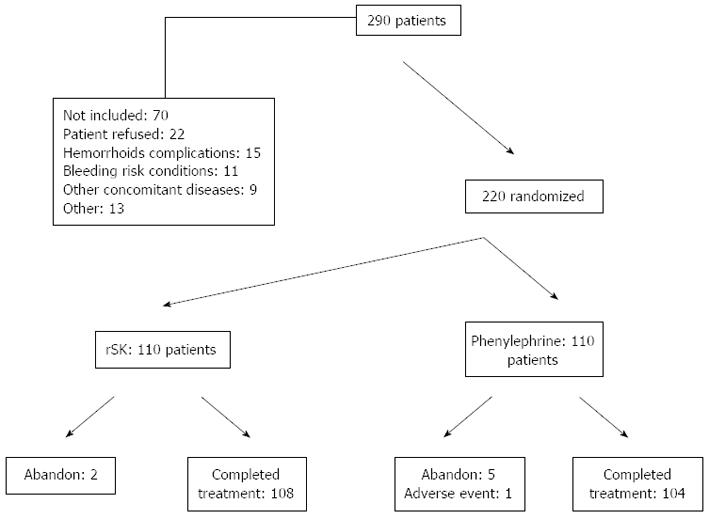

From November 2009 to March 2010 a total of 220 patients were included out of 290 that were screened. Their disposition is shown in Figure 1. The main causes for non-inclusion were refusal to consent, hemorrhoidal disease with excluding complications (infections, abscess, fistula, or due to portal hypertension), bleeding risk conditions (anti-coagulant therapy, recent digestive or urinary bleeding, hemophilia, and recent surgery), other concomitant diseases (acute diarrhea, arterial hypertension, heart failure, hyperthyroidism, and prostate hyperplasia), and other causes (pregnancy, age, allergy, and mental disorders). Out of the 70 non-included subjects, 27 (39%) were due to possible contraindications or precautions of the rSK treatment.

Treatment was completed in 98.2% and 94.5% of the patients from the rSK and phenylephrine groups, respectively. Causes of non-compliance are described in Figure 1. Patients missing the response evaluation visits were one, one, and four in the rSK group on the 3rd, 5th, and 10th day, respectively. In the phenylephrine group the corresponding missing evaluations were none, two, and three.

Table 1 shows the demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients. Most of them were males, 18 to 75 years-old, with the ethnic distribution of the Cuban population. Treatment was started within 6 d after the onset of symptoms in 75% of the subjects. Hemorrhoids were 66% external and 53% with thrombosis. Symptoms presented for the first time in 42% of the patients, 15% had previous thrombectomy, and three subjects had history of hemorrhoidectomy. No relevant imbalances between the groups can be seen.

| rSK (n = 110) | Phenylephrine (n = 110) | Total (n = 220) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male/female (% male) | 58/52 (52.7) | 66/44 (60.0) | 124/96 (56.4) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| White | 60 (54.5) | 56 (50.9) | 116 (52.7) |

| Black | 13 (11.8) | 16 (14.5) | 29 (13.2) |

| Mestizo | 37 (33.6) | 38 (34.5) | 75 (34.1) |

| Age (yr) | |||

| Median ± QR (range) | 46 ± 20 (18-74) | 45 ± 18 (21-75) | 45 ± 19 (18-75) |

| Days from start of symptoms to treatment onset | |||

| Median ± QR (range) | 3 ± 2 (0-26) | 3 ± 3 (0-38) | 3 ± 3 (0-38) |

| Classification of the hemorrhoids | |||

| External | 73 (66.4) | 73 (66.4) | 146 (66.4) |

| Internal | 31 (28.2) | 30 (27.3) | 61 (27.7) |

| Mixed | 6 (5.5) | 7 (6.4) | 13 (5.9) |

| Grade of prolapse (I or II:III or IV) | (13:24) | (7:30) | (20:54) |

| Presence of thrombosis | 59 (53.6) | 57 (51.8) | 116 (52.7) |

| Debut of disease | 48 (43.6) | 44 (40.0) | 92 (41.8) |

| Previous thrombectomy | 17 (15.5) | 16 (14.5) | 33 (15.0) |

| Previous hemorrhoidectomy | 2 (1.8) | 1 (0.9) | 3 (1.4) |

Table 2 shows the results of the clinical evaluations. The analyses were “intention-to-treat” and involved all patients who were randomly assigned. A significant treatment-dependence of the complete response rate was obtained for the main trial outcome, at 5 d. The rSK suppositories treated group showed 75% complete response rate, as expected and a > 40% advantage over the control group. A multilevel analysis did not yield relevant differences among the participating hospitals regarding this main trial outcome (result not shown). Secondary outcome evaluations, at 3 and 10 d yielded highly significant differences as well. Time to response was 5 d shorter in the rSK group.

| rSK (n = 110) | Phenylephrine (n = 110) | P value | |

| Response after 3 d | 41 (37.3) | 7 (6.4) | < 0.0011 |

| Response after 5 d (95%CI)3 | 83 (75.5%; 67.4-83.5)3 | 36 (32.7%; 24.0-41.5)3 | < 0.00113 |

| Difference (95%CI)3 | 42.7 (30.5-54.2)3 | ||

| Response after 10 d | 92 (83.6) | 64 (58.2) | < 0.0011 |

| Days to response: median (95%CI) | 5 (4.8-5) | 10 (9.8-10) | 0.0312 |

Complete response rate was > 74% in all subgroups treated with rSK, regardless of the hemorrhoid classification or type of acute event (Table 3). A significant advantage of the rSK treatment was found for all subgroups except for patients with prolapse grades I or II. Besides the small sample size, response rate with phenylephrine was higher among these less complicated cases. Thrombectomy was needed in very few cases but a significant treatment-dependence was detected.

| rSK | Phenylephrine | P value | |

| Type of acute event | |||

| Without thrombosis | 38/51 (74.5) | 15/53 (28.3) | < 0.00011 |

| With thrombosis | 45/59 (76.3) | 21/57 (36.8) | < 0.00011 |

| Thrombectomy | 1/59 (1.7) | 8/57 (14.0) | 0.0162 |

| Hemorrhoid classification | |||

| External | 54/73 (74.0) | 22/73 (30.1) | < 0.00011 |

| Internal + mixed | 29/37 (78.4) | 14/37 (37.8) | < 0.00011 |

| Prolapse grade | |||

| I or II | 11/13 (85) | 4/7 (57) | 0.292 |

| III or IV | 18/24 (75) | 10/30 (33) | 0.0021 |

A total of 45 and 33 adverse events (AE) were reported in the phenylephrine and rSK groups, respectively. The AE that appeared in more than one patient are shown in Table 4. Most reports were mild or moderate. Only three events were severe: one patient with local pain and burning sensation in the phenylephrine group and one with local pain in the rSK group. Only a tachycardia immediately after the application of the phenylephrine suppository in one patient was considered with definite causality relation with treatment. The rest of the AE could be explained by the underlying illness. None of them required specific treatment.

| rSK (n = 110) | Phenylephrine (n = 110) | |

| Total subjects with adverse events | 19 (17.3) | 30 (27.3) |

| Events | ||

| Local burning sensation | 3 (2.7) | 11 (10.0) |

| Local pricking sensation | 4 (3.6) | 9 (8.2) |

| Rectal bleeding | 5 (4.5) | 4 (3.6) |

| Anal pruritus | 3 (2.7) | 5 (4.5) |

| Diarrhea | 4 (3.6) | 0 |

| Headache | 1 (0.9) | 3 (2.7) |

| Anal pain | 3 (2.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Local heat sensation | 0 | 2 (1.8) |

This work reports for the first time the therapeutic efficacy of rSK suppositories on acute hemorrhoids in a randomized trial, compared to a commonly used treatment. This active control was preferred to a placebo, due to ethical considerations, since it was not possible to exclude patients from an accepted therapy. On the other hand no reports of the quantitative effect of phenylephrine-based preparations on the resolution of acute hemorrhoidal illness were found, either from controlled clinical trials or not[21,22]. The sample size of the study was enough to fulfill its aim. The multicentric character of the trial, with several provinces involved, contributes to the generalizability (external validity, applicability) of the findings. A double-blind design was not possible in this case since the products had different presentations and schedules. A double-dummy scheme (each active drug with the alternate placebo) would had been little feasible and ethically questionable, given the acute character of the condition to treat and the uncomfortable way of administration. However, central randomization, its concealment, and active monitoring, minimized this source of bias. The trial performed well, without deviations and minimal dropouts. This was facilitated by the fact that treatment was short lasting, simple, and inclusion could be completed easily. Therefore the internal validity of the study was adequate.

The trial hypothesis was fulfilled: a > 70% complete response rate was obtained on the 5th day in the rSK treated group and the advantage over the control group was > 40%, far above the expected difference. The difference found at the 3rd day indicates that the effect begins shortly after treatment. At 10 d more than 80% of the patients treated with rSK had responded completely and the difference with the control group was 25% despite the fact that the natural course of the acute event leads to its resolution. The results confirm the previous evidence of effect found for this product[15,16]. As expected, a better outcome was achieved with the extended treatment schedule from 24 to 48 h.

The median time-to-complete response was shortened in 5 d with respect to the phenylephrine preparation. The shorter response time is an interesting result with a potential impact on patients’ quality of life. This illness frequently affects active population that needs to return as soon as possible to their usual doings[3,10,23-25].

Other larger studies have reported longer healing periods with control standard treatments and other agents. Greenspon et al[23] reported that conservatively treated thrombosed external hemorrhoid patients required 24 d to complete symptom resolution as compared to 3.9 d with surgical management. Menteş et al[24] report an 86.2% success rate at two weeks with oral calcium dobesilate in acute attacks of internal hemorrhoids. Perrotti et al[25] report that thrombosed hemorrhoids can be treated at home and usually settle within 10-14 d using ice packs, stool softeners, and analgesia.

Subgroup analyses showed the efficacy for all clinical variants of acute hemorrhoids including all grades of prolapse. The differences were large enough to exclude that any of these significant findings were from chance alone. Only in the less complicated prolapse grades I or II, the difference between rSK and control groups was not statistically significant, although clinically interesting. The sample size in this subgroup was quite small and the response in the controls was higher, which is not unexpected for a milder condition.

Need for thrombectomy was 14% in the control group, similar to other reports[7]. The rSK treated group showed a much smaller thrombectomy rate, in agreement with the previous trial with this product[16] and its proposed mechanism of action as a thrombolytic agent. This is an exciting result since thrombectomy is indicated when conservative management fails to improve the patient’s main complaint (anal pain). To be able to avoid an aggressive approach can be interesting due to the possible medical and financial consequences to the patient and/or healthcare system. Since thrombosis is a frequent complication of hemorrhoidal disease (53% in this series) the possibility of a non-surgical approach would be beneficial to a significant number of patients.

The results indicate that the rSK suppository is safe and tolerable. The adverse events reported were minimal, mild, resolved spontaneously and with low causality relation with the rSK. In the same sense, there were no bleeding complications in the rSK group. In fact, bleeding as a symptom of the underlying disease cleared adequately in this group. It was previously shown that rSK suppositories application does not alter systemic hemostasis[15]. On the contrary, the only event that caused treatment interruption was a phenylephrine-related tachycardia episode, expected with an alpha-adrenergic agent.

Several local host factors may influence absorption in the rectum: the mucus layer, the variable volume of rectal fluid, the basal cell membrane, the tight junctions and the intracellular compartments may each constitute local barriers to drug absorption, depending on histological factors and on the molecular structure of the administered drug[17], a > 40 kDa protein in this case. At the same time there are arteriovenous shunts as well as communications between the internal and external plexus that makes the submucosal space in the rectal duct as a vascular sponge[26] that can explain the effect of rSK even if only a small amount is absorbed. The thrombolytic effect of the rSK suppository on microthrombi in the local capillary structures could improve permeability and its action on the lymphatic local system, which could diminish the inflammation, exudates, and local edema. This determines a rapid improvement after the product is applied, even if macrothrombosis is not present.

The results of this trial show that the rSK suppository preparation significantly advantages the widely used over-the-counter phenylephrine control preparation for the treatment of acute hemorrhoidal illness, with an adequate safety profile. Further controlled, large trials should confirm this efficacy data, compare them with other products established in usual medical practice and explore other schedules in order to optimize the cost-benefit ratio.

The authors wish to acknowledge the National Colo-proctology Group from the Public Health Ministry of Cuba for its support.

Hemorrhoids are the most frequent proctologic illness, being a worldwide health problem. Although several medicines have been tested, significant benefits have not been obtained to control this condition. When response is obtained the result takes many d and in an important group of patients surgical or other invasive procedures are indicated (hemorrhoidectomy, ligation, sclerotherapy, infrared photoclotting, cryo and laser therapy), not exempted from complications. Streptokinase (SK) is a fibrinolytic agent. Its efficacy of SK has been demonstrated in acute myocardial infarct and in other thrombotic diseases. Its local application on hemorrhoids, where thrombosis and/or inflammation with microthrombi may be present was first tested in exploratory trials where a 200000 IU suppository showed a beneficial effect on hemorrhoidal symptoms (36% larger response rate, 5 d faster), over excipient controls, with an adequate safety profile. These were the first reports of a thrombolytic treatment for this condition. The aim of the present work was to compare the efficacy and safety of 200000 IU SK suppositories vs a phenylephrine-based over-the-counter available suppository for the treatment of acute hemorrhoids through a multicenter, randomized clinical trial.

Medical treatments for haemorrhoidal crisis come very seldom from randomised, controlled clinical trials. The paper describes that a candidate to a new therapeutic alternative, based on thrombolysis, shows significant efficacy advantage with respect to a widely used over-the-counter hemorrhoidal product.

The results of this trial show that the SK suppository preparation significantly advantages the widely used over-the-counter phenylephrine control preparation for the treatment of acute hemorrhoidal illness (75% response rate at 5 d vs 33% with the control), with an adequate safety profile.

These results lead to a new first-in-class treatment for such a common disease. Further controlled, large trials should confirm these efficacy data and compare them with other products established in usual medical practice.

Fibrinolysis: breakdown of fibrin that forms the clots that occlude blood flow in veins or arteries. Streptokinase: indirect fibrinolytic agent that interacts with plasminogen, forming an active complex with protease action that activates plasminogen into plasmin, which is the direct fibrinolytic enzyme.

It is a well-conducted trial with impressive results. This is a well designed, well conducted and well written study. The multicenter nature of the study and inclusion of the study along with inclusion of sufficient number of patients from different ethnic groups and with different grades of hemorrhoids indicates good generalisability of the study. The results demonstrate early initiation of action, short response time and high healing rate in patients treated with recombinant streptokinase, which is of great clinical benefit.

P- Reviewers: Hadianamrei R, Picchio M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Ganz RA. The evaluation and treatment of hemorrhoids: a guide for the gastroenterologist. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:593-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lohsiriwat V. Hemorrhoids: from basic pathophysiology to clinical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2009-2017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 263] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 3. | Sanchez C, Chinn BT. Hemorrhoids. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:5-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Acheson AG, Scholefield JH. Management of haemorrhoids. BMJ. 2008;336:380-383. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Riss S, Weiser FA, Schwameis K, Riss T, Mittlböck M, Steiner G, Stift A. The prevalence of hemorrhoids in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27:215-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cintron J, Abacarian H. Benign anorectal: hemorrhoids. The ASCRS of Colon and Rectal Surgery. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag 2007; 156-177. |

| 7. | de Miguel M, Oteiza F, Ciga MA, Ortiz H. [The surgical treatment of hemorrhoids]. Cir Esp. 2005;78 Suppl 3:15-23. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Herold A, Joos A, Bussen D. [Operations for hemorrhoids: indications and techniques]. Chirurg. 2012;83:1040-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Evans CFM, Hyder SA, Middleton SB. Modern surgical management of haemorrhoids. Pelviperineol. 2008;27:139-142. |

| 10. | Hull T. Examination and Diseases of the Anorectum. Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 7th ed. Philadelphia: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s 2002; 2277-2293. |

| 11. | Zhu J, Ding JH, Zhao K, Zhang B, Zhao Y, Tang HY, Zhao YJ. [Complications after procedure for prolapse and hemorrhoids for circular hemorrhoids]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Zazhi. 2012;15:1252-1255. [PubMed] |

| 12. | GISSI-2: a factorial randomised trial of alteplase versus streptokinase and heparin versus no heparin among 12,490 patients with acute myocardial infarction. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico. Lancet. 1990;336:65-71. [PubMed] |

| 13. | TERIMA Group of Investigators. TERIMA-2: national extension of thrombolytic treatment with recombinant streptokinase in acute myocardial infarct in Cuba. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:949-954. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cáceres-Lóriga FM, Pérez-López H, Morlans-Hernández K, Facundo-Sánchez H, Santos-Gracia J, Valiente-Mustelier J, Rodiles-Aldana F, Marrero-Mirayaga MA, Betancourt BY, López-Saura P. Thrombolysis as first choice therapy in prosthetic heart valve thrombosis. A study of 68 patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2006;21:185-190. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Quintero L, Hernández-Bernal F, Marrero MA, Valenzuela CM, López M, Barcelona S, Ibargollín R, Bobillo H, Aguilera A, Bermúdez Y. Initial evidence of safety and clinical effect of recombinant streptokinase suppository in acute hemorrhoidal disease. Open, proof-of-concept, pilot trial. BA. 2010;27:277-280. |

| 16. | Hernández-Bernal F, Valenzuela-Silva CM, Quintero-Tabío L, Castellanos-Sierra G, Monterrey-Cao D, Aguilera-Barreto A, López-Saura P. Recombinant streptokinase suppositories in the treatment of acute haemorrhoidal disease. Multicentre randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial (THERESA-2). Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:1423-1428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Gupta PJ. Suppositories in anal disorders: a review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11:165-170. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Estrada MP, Hernández L, Pérez A, Rodríguez P, Serrano R, Rubiera R, Pedraza A, Padrón G, Antuch W, de la Fuente J. High level expression of streptokinase in Escherichia coli. Biotechnology (NY). 1992;10:1138-1142. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Kaidar-Person O, Person B, Wexner SD. Hemorrhoidal disease: A comprehensive review. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:102-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Naranjo CA, Shear NH, Busto U. Adverse drug reactions. Principles of medical pharmacology. 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press 1998; 791-800. |

| 21. | Chan KK, Arthur JD. External haemorrhoidal thrombosis: evidence for current management. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:21-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Greenspon J, Williams SB, Young HA, Orkin BA. Thrombosed external hemorrhoids: outcome after conservative or surgical management. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47:1493-1498. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Menteş BB, Görgül A, Tatlicioğlu E, Ayoğlu F, Unal S. Efficacy of calcium dobesilate in treating acute attacks of hemorrhoidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:1489-1495. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Perrotti P, Antropoli C, Molino D, De Stefano G, Antropoli M. Conservative treatment of acute thrombosed external hemorrhoids with topical nifedipine. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44:405-409. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Foster ME, Lancaster JF, Leaper DJ. Functional aspects of ano-rectal vascularity. Acta Anat (Basel). 1985;123:30-33. [PubMed] |