Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18452

Revised: June 9, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 258 Days and 10.3 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the differences in the treatment outcomes between the unresectable and recurrent biliary tract cancer patients who received chemotherapy.

METHODS: Patients who were treated with gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy in the previous prospective studies were divided into groups of unresectable and recurrent cases. The tumor response, time-to-progression, overall survival, toxicity, and dose intensity were compared between these two groups.

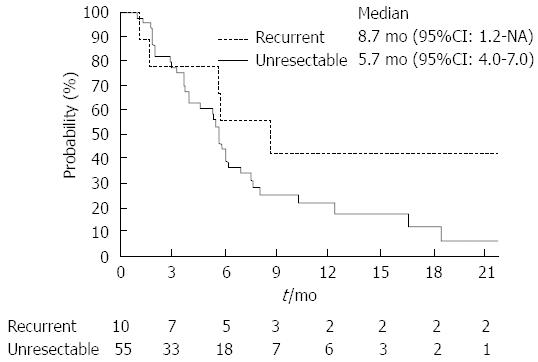

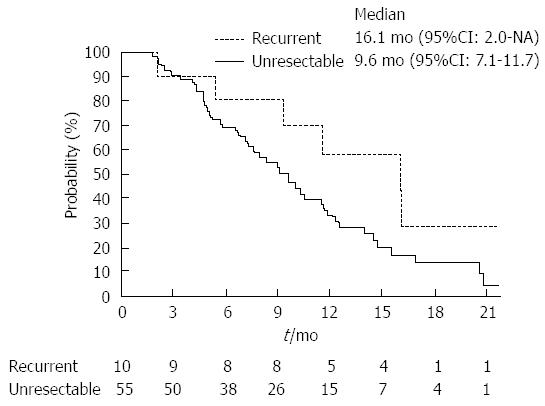

RESULTS: Response rate of the recurrent group was higher than that of the unresectable group (40.0% vs 25.5%; P = 0.34). Median time-to-progression of the recurrent and unresectable groups were 8.7 mo (95%CI), 1.2 mo, not reached) and 5.7 mo (95%CI: 4.0-7.0 mo), respectively (P = 0.14). Median overall survival of the recurrent and the unresectable groups were 16.1 mo (95%CI: 2.0 mo-not reached) and 9.6 mo (95%CI: 7.1-11.7 mo), respectively (P = 0.10). Dose intensities were significantly lower in the recurrent groups (gemcitabine: recurrent group 83.5% vs unresectable group 96.8%; P < 0.01, S-1: Recurrent group 75.9% vs unresectable group 91.8%; P < 0.01). Neutropenia occurred more frequently in recurrent group (recurrent group 90% vs unresectable group 55%; P = 0.04).

CONCLUSION: Not only the efficacy but also the toxicity and dose intensity were significantly different between unresectable and recurrent biliary tract cancer.

Core tip: Many chemotherapeutic studies of advanced biliary tract cancer include both unresectable and recurrent cases. However, the treatment outcomes of these two conditions might be different. We therefore conducted a pooled analysis of two prospective studies to evaluate the differences in the treatment outcomes between the unresectable and recurrent cases in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer patients who received chemotherapy. From our pooled analysis, not only the efficacy but also the toxicity and dose intensity were significantly different between these two conditions. Therefore, it is better to evaluate the unresectable and recurrent cases separately in future prospective studies.

- Citation: Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Ito Y, Yasuda I, Toda N, Yagioka H, Matsubara S, Hanada K, Maguchi H, Kamada H, Hasebe O, Mukai T, Okabe Y, Maetani I, Koike K. Treatment outcomes of chemotherapy between unresectable and recurrent biliary tract cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(48): 18452-18457

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i48/18452.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18452

Gemcitabine and cisplatin (GC) combination therapy is currently the standard care for the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer (BTC)[1-4]. The efficacies of GC combination therapy were also confirmed in a study with Japanese patients[5-9]. However, this study highlighted the differences of efficacy between the unresectable and recurrent cases. In fact, the median overall survival of unresectable and recurrent cases was 9.4 mo and 16.1 mo, respectively.

Extended surgeries, such as a major hepatectomy or a pancreatoduodenectomy, were usually performed for the treatment of BTC. The patients who received these extended surgeries did not usually tolerate the standard dose of chemotherapy and needed dose modifications[10]. In adjuvant settings, dose modifications were needed, especially after a major hepatectomy, when the patients were treated with gemcitabine and S-1 (GS) combination therapy[11-13]. However, the same treatment regimens were often delivered for the recurrent cases. Because there is currently no study that evaluates the differences of dose intensity between unresectable and recurrent cases, it is unknown if patients with recurrent tumors can tolerate the standard dose of chemotherapy.

Therefore, we conducted a pooled analysis using two prospective study data to clarify differences in the treatment outcomes between unresectable and recurrent cases receiving GS combination therapy in patients with advanced BTC. GS combination therapy is one of the promising regimens for advanced BTC, and a phase III study comparing GS with GC combination therapy has started in Japan[14-17].

Data from patients treated with GS combination therapy were collected from two prospective studies: the phase II study of GS combination therapy and the randomized phase II study comparing GS combination therapy vs gemcitabine monotherapy[14,16]. The same study group conducted these two prospective studies, and the treatment regimens and assessments were the same between these two studies. The enrolled patients were divided into unresectable and recurrent groups and were used to compare the treatment outcomes.

Gemcitabine was given intravenously at 1000 mg/m2 over 30 min on days 1 and 15, repeated every 4 wk. S-1 was administered orally, twice daily from days 1 to 14, followed by a 2-wk rest. Three doses of S-1 were established according to the body surface area (BSA) as follows: BSA < 1.25 m2, 80 mg/d; 1.25 m2≤ BSA < 1.5 m2, 100 mg/d; and BSA ≥ 1.5 m2, 120 mg/d. The dose reduction was based on any adverse effects graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria of Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0. In the case of a grade 3/4 hematological toxicity or a grade 2 or higher non-hematological toxicity, the treatment was temporarily suspended. After confirming the resolution to a grade 1 toxicity level or lower, the treatment was restarted at a reduced dose. At first, S-1 was reduced to the following doses: BSA < 1.25 m2, 60 mg/d; 1.25 m2≤ BSA < 1.5 m2, 80 mg/d; and BSA ≥ 1.5 m2, 100 mg/d. If the toxicity occurred despite S-1 reduction, the gemcitabine dose was reduced to 800 mg/m2. If further toxicity was observed, the dose was reduced again. The S-1 dose was reduced to the following doses: BSA < 1.25 m2, 40 mg/d; 1.25 m2≤ BSA < 1.5 m2, 60 mg/d; and BSA ≥ 1.5 m2, 80 mg/d, and the gemcitabine dose was reduced to 600 mg/m2. If further dose reduction was needed, the study treatment was put on hold. No dose re-escalation was allowed. The study treatments were continued until the disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patients’ refusal.

The pretreatment evaluation included a medical history and physical examination, a complete blood count, a serum biochemical test, urinalysis and an echocardiogram. The Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and laboratory tests that included complete blood counts and serum biochemical tests were checked every two weeks. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) levels were measured at the beginning of the study and at day 1 of each cycle. Pretreatment evaluation using contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was conducted within 4 wk before enrollment of the patients. The tumor response was assessed every two cycles, and the toxicity was evaluated using CTCAE version 3.0.

The objective response rate was evaluated according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.0[18]. The time-to-progression and overall survival were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the patients’ characteristics and tumor responses between the two groups. The Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare quantitative variables as appropriate. The log-rank tests were used to compare the survival curves (overall survival and time-to-progression) between the unresectable group and the recurrent group. The JMP 9.0 statistical software program (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) was used for all statistical analyses.

A total of sixty-five patients were enrolled in this pooled analysis. Fifty-five patients were included in the unresectable group and ten patients were in the recurrent group (Table 1). The baseline characteristics were well balanced between these two groups, with the exception of the baseline sum of longest diameter (BSLD). The median BSLDs of the unresectable and recurrent groups were 9.0 cm (range: 1.0-31.9 cm) and 2.8 cm (range: 1.2-16.0 cm), respectively (P = 0.04). In ten patients who were enrolled in the recurrent group, two patients had received a major hepatectomy, and a pancreatoduodenectomy was performed in three patients. One patient received a hepatopanceratoduodenectomy, and a cholecystectomy was performed in four patients.

| Unresectable(n = 55) | Recurrent(n = 10) | P value | |

| Age (median, range) | 68 (47-83) | 70 (51-79) | 0.43 |

| Sex (male / female) | 31/24 | 7/3 | 0.42 |

| ECOG performance status | 0.76 | ||

| 0 | 28 (51) | 6 (60) | |

| 1 | 25 (45) | 4 (40) | |

| 2-3 | 2 (4) | 0 | |

| Primary biliary site | 0.07 | ||

| Gallbladder | 26 (47) | 4 (40) | |

| Intrahepatic bile duct | 20 (36) | 2 (20) | |

| Extrahepatic bile duct | 9 (16) | 3 (30) | |

| Ampulla of Vater | 0 | 1 (10) | |

| Baseline sum of longest diameter(median, range, cm) | 9 (1.0-31.9) | 2.8 (1.2-16.0) | 0.04 |

Table 2 summarizes the results of tumor responses. The response rate of the recurrent group was higher than that of the unresectable group (40.0% vs 25.5%; P = 0.34). Two patients in the recurrent group achieved complete responses. The disease control rate was similar between these two groups. The median time-to-progression of the recurrent and unresectable groups were 8.7 mo (95%CI: 1.2 mo-not reached) and 5.7 mo (95%CI: 4.0-7.0 mo), respectively (Figure 1; P = 0.14). Moreover, the median overall survival of the recurrent and the unresectable groups were 16.1 mo (95%CI: 2.0 mo-not reached) and 9.6 mo (95%CI: 7.1-11.7 mo), respectively (Figure 2; P = 0.10).

| Unresectable(n = 55) | Recurrent(n = 10) | P value | |

| Complete response | 0 | 2 (20.0) | |

| Partial response | 14 (25.5) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Stable disease | 29 (52.7) | 3 (30.0) | |

| Progressive disease | 10 (18.2) | 2 (20.0) | |

| Not evaluable | 2 (3.6) | 1 (10.0) | |

| Response rate | 25.5% | 40.0% | 0.34 |

| Disease control rate | 78.2% | 70.0% | 0.57 |

The median treatment cycles between the unresectable and the recurrent groups were 4 and 7.5 cycles, respectively (P = 0.15; Table 3). The dose intensities were significantly lower in the recurrent groups than in the unresectable group of both gemcitabine and S-1 treatments.

| Unresectable(n = 55) | Recurrent(n = 10) | P value | |

| Treatment cycle | |||

| Median, range | 4 (1-26) | 7.5 (1-23) | 0.15 |

| Dose intensity (overall) | |||

| Gemcitabine | 96.8% | 83.5% | < 0.01 |

| S-1 | 91.8% | 75.9% | < 0.01 |

| Dose intensity (first two cycles) | |||

| Gemcitabine | 95.3% | 89.4% | 0.13 |

| S-1 | 90.7% | 78.9% | 0.04 |

The incidences of major adverse events are presented in Table 4. The incidence of each adverse event was not statistically significant between these two groups except for neutropenia in all grades (recurrent group 90% vs unresectable group 55%; P = 0.04). Grade 3-4 neutropenia was also more frequent in the recurrent group than in the unresectable group (60% vs 29%; P = 0.08). Leukopenia occurred in all grades more frequently in the recurrent group than in the unresectable group (90% vs 60%; P = 0.08).

| Unresectable(n = 55) | Recurrent(n = 10) | |||

| All grades | Grade 3-4 | All grades | Grade 3-4 | |

| Hematological | ||||

| Leukopenia | 33 (60) | 16 (29) | 9 (90) | 2 (20) |

| Neutropenia | 30 (55) | 16 (29) | 9 (90) | 6 (60) |

| Anemia | 41 (75) | 9 (16) | 7 (70) | 1 (10) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 25 (45) | 9 (16) | 5 (50) | 0 |

| Non-hematological | ||||

| Nausea | 12 (22) | 1 (2) | 4 (40) | 0 |

| Vomiting | 3 (5) | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Anorexia | 19 (35) | 2 (4) | 4 (40) | 0 |

| Stomatitis | 14 (25) | 0 | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 7 (13) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Constipation | 16 (29) | 0 | 1 (10) | 0 |

| Pigmentation | 12 (22) | 0 | 3 (30) | 0 |

| Skin rash | 10 (18) | 3 (5) | 2 (20) | 0 |

| Liver dysfunction | 7 (13) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 |

From this pooled analysis, there were several differences in the treatment outcomes between the unresectable and recurrent groups. The median overall survival, the median time-to-progression, and the response rate were better in the recurrent group when compared with the unresectable group. Furthermore, the dose intensity and toxicities were also different between these two groups.

The BSLD was significantly smaller in the recurrent group than in the unresectable group. BSLD is evaluated as the representative of the tumor volume using RECIST criteria. The patients who received surgery are checked for the recurrence by a specific interval, and thus, the recurrence is usually found as a smaller tumor size. However, BTC are sometimes diagnosed at an advanced stage with a larger tumor volume because some BTC lack the characteristic symptoms. The resection rate of BTC in Japan was reported at more than 70%[19]. Therefore, the tumor volumes of unresectable cases usually become large. We hypothesized that the differences of treatment outcomes were mainly affected by the different tumor sizes between these two groups[20,21].

Major hepatectomies or pancreatoduodenectomies are surgeries often performed for the treatment of BTC. The metabolism of anti-cancer agents is often influenced by a pancreatoduodenectomy[10]. Moreover, a report of a phase 1 study evaluated the recommended dose of GS combination therapy in the adjuvant setting for advanced BTC[11]. A dose reduction was mainly needed after a major hepatectomy when GS combination therapy was used in the adjuvant setting. Although it has not become clear that dose modification was also needed in the recurrent setting, the dose intensity was lower and the adverse events of leucopenia and neutropenia were more frequent in the recurrent group in our study. Therefore, we will need to discuss whether the same regimen can be used both for the unresectable and recurrent cases in the field of advanced BTC.

In clinical studies of advanced BTC, all patients with cancers from all biliary sites were enrolled despite the difference in clinical condition of each biliary site. The prognosis of patients with gallbladder cancers was considered to be poorer than that of other biliary sites[22,23]. However, it is still difficult to evaluate each biliary site separately because of the low accrual rate of clinical study in this field. Because the dose intensities are not usually different between each biliary site, it is reasonable to use the same regimen and to evaluate the treatment outcomes by subset analysis.

The limitation of this pooled analysis was that only a small number of patients were enrolled. Therefore, some data may not be able to detect the significance statistically. However, this pooled analysis might be the first report to evaluate the differences of the treatment outcomes in detail from the data of a prospective study in the field of advanced BTC[24]. It is very important to use the prospectively collected data to evaluate the toxicities precisely. Another limitation was that this analysis was based on the data of GS combination therapy. GC combination therapy is now the standard of care for advanced BTC in the world. Although GS combination therapy is thought to be a promising regimen in Japan and a phase III study comparing GS with GC combination therapy has started, the influence of extended surgery might be different when a different chemotherapeutic agent is used for treatment. Therefore, further assessment is needed to confirm differences in treatment outcomes for GC combination therapy[25].

In conclusion, not only the efficacy but also the dose intensity and toxicity were different between unresectable and recurrent BTC. The treatment outcomes (response rate, time-to-progression, and overall survival) were better in recurrent cases and are possibly due to the small tumor volume. The dose intensity was significantly lower in recurrent cases, possibly due to the extended surgery. Although the enrollment of patients with advanced BTC for clinical study is still difficult, it may be better to enroll those with unresectable and recurrent BTC separately in future studies.

Biliary tract cancer is a rare cancer worldwide. Obstructive jaundice and infection to the biliary system usually become obstacles to introduce chemotherapy. Therefore, enrollment of clinical trial for advanced biliary tract cancer is more difficult than other common cancers and both unresectable and recurrent cases were included in the same chemotherapeutic studies in this field.

Many chemotherapeutic studies of advanced biliary tract cancer include both unresectable and recurrent cases. However, the treatment outcomes of these two conditions might be different. The authors therefore conducted a pooled analysis of two prospective studies to evaluate the differences in the treatment outcomes between the unresectable and recurrent cases in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer patients who received chemotherapy.

From these pooled analysis, not only the efficacy but also the toxicity and dose intensity were significantly different between these two conditions.

Because the treatment outcomes were significantly different between unresectable and recurrent biliary tract cancer, it is better to evaluate these two conditions cases separately in future prospective studies.

Biliary tract cancer includes cholangiocarcinoma, gallbladder cancer, and ampullary carcinoma. Gemcitabine is a nucleoside analog used for chemotherapy. S-1 is an oral fluoropyrimidine widely used in Japan. Baseline sum of longest diameter is evaluated as the representative of the tumor volume using RECIST criteria.

Generally, this is an interesting topic. The incidence rate of biliary tract cancer is not as high as hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, the main limitation of this paper is the small sample size with all its inherent defects.

P- Reviewer: Tiberio GAM, Zhong JH S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Valle J, Wasan H, Palmer DH, Cunningham D, Anthoney A, Maraveyas A, Madhusudan S, Iveson T, Hughes S, Pereira SP. Cisplatin plus gemcitabine versus gemcitabine for biliary tract cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1273-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2617] [Cited by in RCA: 3169] [Article Influence: 211.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Koike K. Current status of chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2013;28:515-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Furuse J, Kasuga A, Takasu A, Kitamura H, Nagashima F. Role of chemotherapy in treatments for biliary tract cancer. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:337-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tada M, Nakai Y, Sasaki T, Hamada T, Nagano R, Mohri D, Miyabayashi K, Yamamoto K, Kogure H, Kawakubo K. Recent progress and limitations of chemotherapy for pancreatic and biliary tract cancers. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;2:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Okusaka T, Nakachi K, Fukutomi A, Mizuno N, Ohkawa S, Funakoshi A, Nagino M, Kondo S, Nagaoka S, Funai J. Gemcitabine alone or in combination with cisplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer: a comparative multicentre study in Japan. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:469-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 570] [Cited by in RCA: 568] [Article Influence: 37.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Valle JW, Furuse J, Jitlal M, Beare S, Mizuno N, Wasan H, Bridgewater J, Okusaka T. Cisplatin and gemcitabine for advanced biliary tract cancer: a meta-analysis of two randomised trials. Ann Oncol. 2014;25:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Furuse J, Okusaka T, Bridgewater J, Taketsuna M, Wasan H, Koshiji M, Valle J. Lessons from the comparison of two randomized clinical trials using gemcitabine and cisplatin for advanced biliary tract cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2011;80:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Mizuno S, Yamamoto K, Yagioka H, Yashima Y, Kawakubo K, Kogure H, Togawa O. Feasibility study of gemcitabine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy for patients with refractory biliary tract cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2011;29:1488-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Takahara N, Akiyama D, Yagioka H, Kogure H, Matsubara S, Ito Y, Yamamoto N. A retrospective study of gemcitabine and cisplatin combination therapy as second-line treatment for advanced biliary tract cancer. Chemotherapy. 2013;59:106-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Muneoka K, Shirai Y, Sasaki M, Wakai T, Sakata J, Kanda J, Wakabayashi H, Hatakeyama K. [Effect of pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy on serum levels of 5-fluorouracil during S-1 treatment for pancreaticobiliary malignancy]. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2010;37:1503-1506. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Takahara T, Nitta H, Hasegawa Y, Itou N, Takahashi M, Nishizuka S, Wakabayashi G. A phase I study for adjuvant chemotherapy of gemcitabine plus S-1 in curatively resected patients with biliary tract cancer: adjusting the dose of adjuvant chemotherapy according to the surgical procedures. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:1127-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hashimoto Y, Nakashima A, Sakabe R, Kobayashi H, Kondo N, Nakagawa N, Sueda T. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and S-1 after surgical resection for advanced biliary carcinoma: outcomes and prognostic factors. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hayashidani Y, Hashimoto Y, Nakamura H, Nakashima A, Sueda T. Adjuvant gemcitabine plus S-1 chemotherapy improves survival after aggressive surgical resection for advanced biliary carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2009;250:950-956. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Ito Y, Kogure H, Togawa O, Toda N, Yasuda I, Hasebe O, Maetani I. Multicenter, phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination chemotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:1101-1107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kanai M, Yoshimura K, Tsumura T, Asada M, Suzuki C, Niimi M, Matsumoto S, Nishimura T, Nitta T, Yasuchika K. A multi-institution phase II study of gemcitabine/S-1 combination chemotherapy for patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:1429-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Ito Y, Yasuda I, Toda N, Kogure H, Hanada K, Maguchi H, Sasahira N. A randomized phase II study of gemcitabine and S-1 combination therapy versus gemcitabine monotherapy for advanced biliary tract cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2013;71:973-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Morizane C, Okusaka T, Mizusawa J, Takashima A, Ueno M, Ikeda M, Hamamoto Y, Ishii H, Boku N, Furuse J. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine plus S-1 versus S-1 in advanced biliary tract cancer: a Japan Clinical Oncology Group trial (JCOG 0805). Cancer Sci. 2013;104:1211-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, Wanders J, Kaplan RS, Rubinstein L, Verweij J, Van Glabbeke M, van Oosterom AT, Christian MC. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205-216. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Miyakawa S, Ishihara S, Horiguchi A, Takada T, Miyazaki M, Nagakawa T. Biliary tract cancer treatment: 5,584 results from the Biliary Tract Cancer Statistics Registry from 1998 to 2004 in Japan. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Togawa O, Kogure H, Ito Y, Yamamoto K, Mizuno S, Yagioka H, Yashima Y. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer receiving chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2011;67:847-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Machida N, Yoshino T, Boku N, Hironaka S, Onozawa Y, Fukutomi A, Yamazaki K, Yasui H, Taku K, Asaka M. Impact of baseline sum of longest diameter in target lesions by RECIST on survival of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2008;38:689-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sasaki T, Isayama H, Nakai Y, Takahara N, Sasahira N, Kogure H, Mizuno S, Yagioka H, Ito Y, Yamamoto N. Improvement of prognosis for unresectable biliary tract cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:72-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yonemoto N, Furuse J, Okusaka T, Yamao K, Funakoshi A, Ohkawa S, Boku N, Tanaka K, Nagase M, Saisho H. A multi-center retrospective analysis of survival benefits of chemotherapy for unresectable biliary tract cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:843-851. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ikezawa K, Kanai M, Ajiki T, Tsukamoto T, Toyokawa H, Terajima H, Furuyama H, Nagano H, Ikai I, Kuroda N. Patients with recurrent biliary tract cancer have a better prognosis than those with unresectable disease: retrospective analysis of a multi-institutional experience with patients of advanced biliary tract cancer who received palliative chemotherapy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2014;21:98-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Toyoda M, Ajiki T, Fujiwara Y, Nagano H, Kobayashi S, Sakai D, Hatano E, Kanai M, Nakamori S, Miyamoto A. Phase I study of adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine plus cisplatin in patients with biliary tract cancer undergoing curative resection without major hepatectomy (KHBO1004). Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:1295-1301. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |