Published online Dec 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18199

Revised: July 7, 2014

Accepted: September 5, 2014

Published online: December 28, 2014

Processing time: 243 Days and 4.2 Hours

AIM: To undertake a randomised pilot study comparing biodegradable stents and endoscopic dilatation in patients with strictures.

METHODS: This British multi-site study recruited seventeen symptomatic adult patients with refractory strictures. Patients were randomised using a multicentre, blinded assessor design, comparing a biodegradable stent (BS) with endoscopic dilatation (ED). The primary endpoint was the average dysphagia score during the first 6 mo. Secondary endpoints included repeat endoscopic procedures, quality of life, and adverse events. Secondary analysis included follow-up to 12 mo. Sensitivity analyses explored alternative estimation methods for dysphagia and multiple imputation of missing values. Nonparametric tests were used.

RESULTS: Although both groups improved, the average dysphagia scores for patients receiving stents were higher after 6 mo: BS-ED 1.17 (95%CI: 0.63-1.78) P = 0.029. The finding was robust under different estimation methods. Use of additional endoscopic procedures and quality of life (QALY) estimates were similar for BS and ED patients at 6 and 12 mo. Concomitant use of gastrointestinal prescribed medication was greater in the stent group (BS 5.1, ED 2.0 prescriptions; P < 0.001), as were related adverse events (BS 1.4, ED 0.0 events; P = 0.024). Groups were comparable at baseline and findings were statistically significant but numbers were small due to under-recruitment. The oesophageal tract has somatic sensitivity and the process of the stent dissolving, possibly unevenly, might promote discomfort or reflux.

CONCLUSION: Stenting was associated with greater dysphagia, co-medication and adverse events. Rigorously conducted and adequately powered trials are needed before widespread adoption of this technology.

Core tip: Benign oesophageal strictures are managed by endoscopic dilatation using balloons or bougies, often requiring costly repeat procedures. Biodegradable stents do not usually require removal and may reduce the need for repeated endoscopy. This pilot multi-site randomized study demonstrates that stenting was associated with greater dysphagia, co-medication and adverse events. The oesophageal tract has somatic sensitivity and the process of the stent dissolving, possibly unevenly, might promote discomfort or reflux. Groups were comparable at baseline and findings are statistically significant but patient numbers were small. Rigorously conducted and adequately powered trials are needed before widespread adoption of this technology.

- Citation: Dhar A, Close H, Viswanath YK, Rees CJ, Hancock HC, Dwarakanath AD, Maier RH, Wilson D, Mason JM. Biodegradable stent or balloon dilatation for benign oesophageal stricture: Pilot randomised controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(48): 18199-18206

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i48/18199.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i48.18199

Benign oesophageal strictures (narrowing of the oesophagus) present with dysphagia of solid or liquid foods, which may result in malnutrition, aspiration, and weight loss. Strictures are conventionally treated by endoscopic dilatation using either a balloon (radially dilating the stricture) or a bougie (dilating the stricture by shearing longitudinal force). Balloon dilatation relieves dysphagia in about 80%-90% of patients although associated with small risks of bleeding and perforation[1] and, in around 30%-40% of patients, the stricture recurs needing repeated endoscopic dilatation[2]. Recurrence appears more common for complex strictures related to radiation therapy, corrosive injury or surgical anastomosis[3]. Repeat dilatation is preferred for refractory strictures when compared to surgery, which is associated with high morbidity rates as well as high risk for patients with comorbidities[4-6].

Balloon endoscopic dilatation involves inflating a polyethylene balloon within the stricture, for a minute or longer, followed by removal. Dilation stretches the narrowed oesophagus by radial distension, widening the lumen of the oesophagus and relieving dysphagia. The biological dynamics of the oesophagus response to short term stretching and the longer-term effects on the oesophageal wall are not well understood. Stretching is believed to disrupt the collagen and elastin fibres in the oesophageal wall, responsible for the fibrotic stricture, and open up the lumen. Most patients respond to the dilatation well and maintain luminal patency of the oesophagus for a reasonable period of time. Some patients have recurrence of their dysphagia as inflammation and ongoing fibrosis may cause the stricture to manifest again after several months.

Benign oesophageal strictures are caused by a number of conditions: injury by acid reflux (peptic strictures); injury by ingestion of acid or alkaline caustic agents (corrosive strictures); radiation induced inflammatory strictures; sequelae of therapeutic endoscopic interventions for early oesophageal cancer and Barrett’s oesophagus (such as endoscopic mucosal resection or photodynamic therapy); post surgical anastomotic strictures[7]; and eosinophilic oesophagitis[8].

Self-expanding plastic or metal stents have been used to dilate benign recurrent oesophageal strictures, as a means of reducing the need for repeated endoscopic balloon/bougie dilatation with mixed results and potential complications of stent migration, hyperplastic tissue ingrowth or overgrowth (metal stents), oesophageal obstruction due to collapsed stent, thoracic pain and disappointing longer-term symptom relief[9-14]. These stents need to be removed after a period of time and there can be complications both at insertion and removal. Mechanistically, a stent’s dilatory effect depends upon the strength and duration of the radial distensile forces that act on the oesophageal wall over a period of time, allowing the oesophagus to remodel around the stent.

Biodegradable stents work to the same principle as removable metal/plastic stents without requiring endoscopic removal since the stent dissolves gradually in-situ, thus avoiding the need for it to be removed. The biodegradable stent under study (SX-ELLA BD Stent, ELLA-CS, s.r.o., Czech Republic®) is made from polydioxanone, a monocrystalline polymer that has been used in monofilament surgical suture materials, and has a 55% crystalline structure. It is degraded in living tissue by hydrolytic attack which breaks down the crystalline structure into smaller fragments of low molecular weight products. Polydioxanone (PDX) has a greater resistance to hydrolytic attack when compared to other biodegradable polymers like polyglycolic acid or polylactic acid, both of which have been used as stents, but with faster degradation times. The longer persistence of the PDX stent is thought to allow adequate time for oesophageal remodelling to take place. Typically the stent maintains integrity and radial distensile force for 6-8 wk, and disintegrates in 11-12 wk following implantation.

A recent review identified 17 case series or reports of PDX biodegradable stents reporting from 1 to 28 patients, with follow-up from 2 to 18 mo and variable complication and clinical success[15]. The review identified a prospective comparison of consecutive patients with refractory benign esophageal strictures receiving either self-expanding plastic stents, biodegradable stents or fully covered self-expanding metal stents (30 in each group)[9]. There were no significant differences in performance between stents although stricture length was significantly associated with higher recurrence of symptoms. No randomized controlled trials comparing biodegradable stents with other stents or with balloon dilatation were identified. Lack of adequately robust evidence for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness formed the rationale of this trial.

The study used a pilot multicentre randomised controlled trial design. Blinding of clinicians and patients was not practicable; recording of symptoms was performed by a single blinded observer at baseline, 3, 6 and 12 mo (research nurse). The trial protocol was registered at inception (ISRTCN 05817794), and a favourable opinion from an NHS research ethics committee and NHS local research management and governance approvals were obtained prior to starting.

Between March 2011 and June 2013, adult symptomatic adult patients diagnosed with a new or existing benign oesophageal stricture were recruited prospectively from participating NHS hospital sites. All participants provided informed consent and were then screened to confirm their eligibility before randomisation.

Inclusion criteria included: written informed consent; confirmed diagnosis of benign oesophageal stricture; aged 18-85 years; at least one previous oesophageal dilatation. Exclusion criteria included: patients with high strictures (within 2 cm of the upper oesophageal sphincter); patients pregnant or not taking appropriate contraception; receiving anti-coagulants; diagnosis of oesophageal cancer (previous or current) or terminal disease; any medical illness inhibiting participation in the view of the recruiting clinician; and patients who lack capacity. Patients were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time.

Randomisation was web-based, stratified by hospital site with a block size of four, allocating patients in a 1:1 ratio to biodegradable oesophageal stent (BS) or standard endoscopic balloon dilatation (ED). To ensure concealment of allocation the recruiting clinician provided patient details before allocation was disclosed.

The biodegradable stent used was CE-marked SX-ELLA Stent Esophageal Degradeable BD, placed by a Consultant Gastroenterologist or Consultant Surgeon experienced in the procedure and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Logistical assistance was available from the distributor of the stent in the United Kingdom (United Kingdom Medical, Sheffield, United Kingdom) if required. Stent size was determined by the length of the stricture, and allowing a minimum 1 cm overlap onto the normal oesophageal mucosa on either side. Two overlapping stents could be used if the stricture exceeded the longest stent size available. The stent was placed endoscopically with radiological fluoroscopic assistance and, where possible, internal markers with contrast injection and the stent radio-opaque markers were used to determine the accurate positioning of the stent.

Endoscopic balloon dilatation followed standard clinical practice. A standard CRE® dilatation balloon (Boston Scientific Corp Inc), either wire guided or non-wire guided, was used as needed. Fluoroscopy was recommended for tight and complex strictures, but might not be required for simple strictures. A luminal diameter of 15 mm was considered successful optimal dilatation: multiple dilatation sessions could be used to achieve this with a frequency of one dilatation every 2-3 wk, with a goal of 15 mm or the maximal achievable diameter if less. Follow up for all patients commenced after the first complete endoscopic dilatation procedure.

Where a procedure used fluoroscopy, the maximum fluoroscopy screening time (exposure time) was 5 minutes for oesophageal stenting (maximum 1 session) or 2.5 min per session for balloon dilatation (with a maximum of 2 sessions anticipated). Exposure equated to a few months natural background radiation. The Health Protection Agency terms this as a very low level of risk to patients.

The primary outcome was the average dysphagia score during the first 6 mo, where dysphagia was patient-assessed on a five-point scale. Secondary analysis of the primary endpoint included average dysphagia scores to 12 mo and area-under curve (AUC) estimates. Sensitivity analyses explored the robustness of findings using repeated measures ANOVA and multiple imputation of missing values, using 6 and 12 mo follow-up data.

Secondary endpoints were assessed at the same visits as the primary outcome but were performed by a non-blinded observer. Secondary endpoints assessed were: the number of repeat endoscopic procedures (therapeutic and diagnostic); adverse events (including hospital admissions); quality of life assessed physically using the surrogate markers of weight; generic quality of life assessment (EuroQol EQ-5D); and resource items.

Adverse events were recorded and categorised for severity (mild, moderate of severe) and relatedness (not, unlikely, possibly, probably, definitely) to intervention as well as for expectedness and resolution.

Although not a formal requirement of a pilot study, a power calculation was performed at the design stage. The dysphagia score uses a five-point severity scale; when averaged over a number of points in time it behaves approximately as a continuous measure. A published case series reported typical standard deviations for dysphagia scores of 0.7-0.8[11]. Assuming an average (clinically worthwhile) difference of 1 point (SD 1.0) when comparing the new intervention to standard care, with α = 0.05 and power 90%, it was estimated 23 patients were required in each group. Allowing for a dropout rate of 10%, the study planned to recruit 50 patients.

Statistical significance was assessed using bootstrapping with 10000 replications for continuous measures and Fisher’s exact test for count data. Secondary significance testing of continuous measures was conducted by Mann-Whitney U (MWU) non-parametric testing. Dysphagia area-under curve (AUC) and QALY scores were estimated using the trapezoidal rule. Consequently 6 mo endpoints were weighted by 0.5 (years) and 12 mo endpoints by one (year).

Multiple imputation of missing values was performed using age at randomisation, gender, weight, height, dysphagia at 0 and 3 mo as predictor variables and dysphagia at 6 and 12 mo as imputed and predictor variables with 10 imputations.

All analyses followed intention-to-treat principles and were conducted using SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) 21 (IBM Corporation, New York, United States).

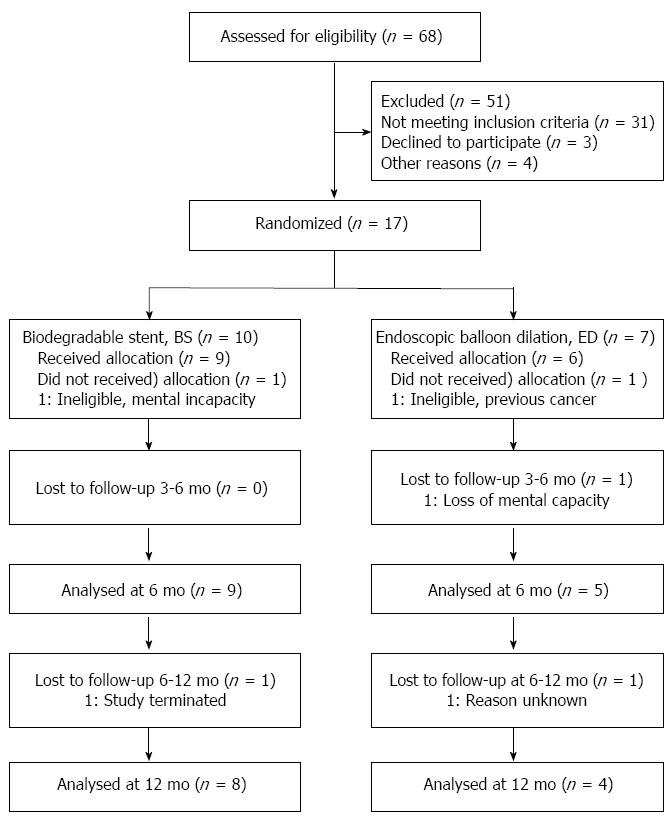

When the study had recruited 17 patients (10 BS and 7 ED), it was agreed with the sponsor to close the study due to low recruitment. One patient from each group was subsequently withdrawn before treatment due to in-eligibility (BS: mental incapacity; ED prior cancer), leaving 9 BS and 6 ED patients for analysis (see Figure 1).

At baseline, BS and ED were similar in demographic and disease history measures (Table 1), and comorbidities (Table 2). Procedural balloon and stent parameters at intervention were within normal expectations (Table 1).

| Endoscopic balloon dilatation | Biodegradable Stent | Mean difference | P value1 | |||||||

| mean ± SD | Min | Max | n | mean ± SD | Min | Max | n | |||

| Age (yr) | 63.8 ± 9.1 | 54 | 74 | 6 | 62.7 ± 12.5 | 40 | 78 | 9 | -1.1 | 1.000 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 61.9 ± 10.5 | 49 | 74 | 6 | 59.6 ± 13.9 | 36 | 77 | 9 | -2.3 | 0.955 |

| Gender male:female | [5:1] | [8:1] | 1.000 | |||||||

| Weight (kg) | 61.0 ± 10.0 | 47 | 71 | 6 | 71.7 ± 29.5 | 45 | 141 | 9 | 10.7 | 0.864 |

| Height (cm) | 168 ± 14 | 143 | 181 | 6 | 170 ± 10 | 156 | 188 | 9 | 2.0 | 1.000 |

| Smoking (never:previously:currently) | (1:2:3) | (4:2:3) | 0.660 | |||||||

| Time since quitting smoking (yr) | 4.3 ± 5.7 | 0.3 | 8.3 | 2 | 1.8 ± 1.5 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 2 | -2.5 | 1.000 |

| n cigarettes/d (if current) | 18.3 ± 2.9 | 15 | 20 | 3 | 18.3 ± 2.9 | 15 | 20 | 3 | 0.0 | 1.000 |

| Current drinker (no:yes) | (3:3) | (4:5) | 1.000 | |||||||

| Alcohol units/w (if current) | 22.3 ± 17.2 | 10 | 42 | 3 | 15.8 ± 11.0 | 1 | 29 | 5 | -6.5 | 0.786 |

| Number of dilatations (ever) | 3.2 ± 2.3 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 6.2 ± 5.1 | 1 | 16 | 9 | 3.0 | 0.224 |

| Number of dilatations (in last 12 m) | 1.2 ± 0.8 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 1.9 ± 1.8 | 0 | 5 | 9 | 0.7 | 0.607 |

| Stricture length (cm)2 | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 2 | 5 | 8 | -0.5 | 0.524 |

| Luminal diameter (mm)2 | 12.3 ± 4.9 | 9 | 18 | 3 | 23.2 ± 31.8 | 6 | 80 | 5 | 10.9 | 1.000 |

| Extent of stricture (from)2 | 31.0 ± 3.7 | 25 | 36 | 6 | 34.6 ± 2.5 | 30 | 38 | 8 | 3.6 | 0.081 |

| Extent of stricture (to)2 | 35.8 ± 2.9 | 32 | 40 | 5 | 38.0 ± 1.9 | 34 | 40 | 8 | 2.2 | 0.171 |

| Dysphagia score (baseline) | 1.83 ± 0.98 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2.00 ± 1.22 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 0.17 | 0.776 |

| EQ5D score (baseline) | 0.69 ± 0.31 | 0.26 | 1 | 6 | 0.69 ± 0.24 | 0.36 | 1 | 9 | 0.00 | 0.955 |

| EQVAS score (baseline) | 73 ± 21 | 35 | 95 | 6 | 57 ± 22 | 30 | 95 | 9 | -16 | 0.145 |

| Intervention balloon dilatation (mm) | 14.5 ± 1.2 | 12 | 15 | 6 | ||||||

| Intervention stent length (mm) | 96.1 ± 31.5 | 60 | 135 | 9 | ||||||

| Intervention fluoroscopy (no:yes) | (4:2) | (0:9) | 0.011 | |||||||

| Endoscopic balloon dilatation (n = 6) | Biodegradable stent (n = 9) | P value1 | |

| Alcohol dependence | 3 (50) | 5 (56) | 1.000 |

| Alcohol overdose | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Appendicitis | 1 (17) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Barrett's oesophagus | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Biliary colic | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Diverticular disease | 2 (33) | 1 (11) | 0.525 |

| Duodenitis | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Reflux disease/oesophagitis | 4 (67) | 3 (33) | 0.315 |

| Haematemesis | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.400 |

| Helicobacter pylori | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.400 |

| Hiatus hernia | 2 (33) | 3 (33) | 1.000 |

| Inguinal hernia | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Ischaemic sigmoid colon stricture | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Oesophageal perforation | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Perforated duodenal ulcer | 1 (17) | 0 (0) | 0.400 |

| Reversal of ileostomy | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

| Wernicke's Encephalopathy | 0 (0) | 1 (11) | 1.000 |

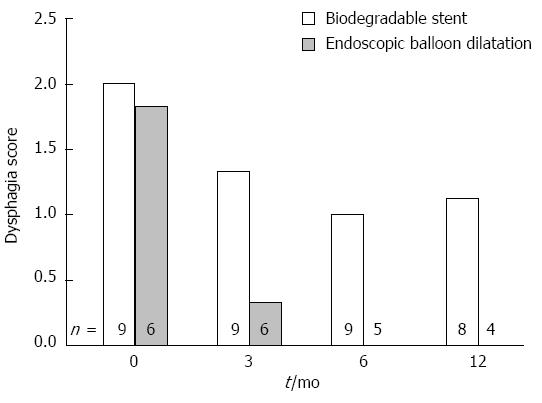

Although both groups improved, average dysphagia score for patients receiving stents remained significantly higher after 6 mo: BS-ED 1.17 (95%CI: 0.63-1.78) P = 0.029. (Table 3, Figure 2) Estimation of dysphagia by AUC method was similar (noting the 0.5 weighting for a 6 mo average). Analysis at 12 mo provided qualitatively similar findings but with borderline statistical significance.

| Endoscopic balloon dilatation | Biodegradable stent | Mean difference | 95%CI | P value1 | P value2 | |||||||

| mean ± SD | Min | Max | n | mean ± SD | Min | Max | n | |||||

| Primary endpoint | ||||||||||||

| Dysphagia Score (Average 3 and 6 m) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5 | 1.17 ± 0.90 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 9 | 1.17 | 0.63-1.78 | 0.029 | 0.004 |

| Secondary endpoints | ||||||||||||

| Dysphagia Score (AUC 0-6 m) | 0.25 ± 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 5 | 0.71 ± 0.46 | 0.25 | 1.50 | 9 | 0.46 | 0.16-0.78 | 0.045 | 0.042 |

| Dysphagia Score (Average 3, 6 and 12 m) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4 | 1.21 ± 1.08 | 0.00 | 3.33 | 8 | 1.21 | 0.56-2.00 | 0.052 | 0.016 |

| Dysphagia Score (AUC 0-12 m) | 0.22 ± 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 4 | 1.28 ± 1.01 | 0.25 | 3.25 | 8 | 1.06 | 0.43-1.81 | 0.066 | 0.008 |

| QALY (EQ5D 0-6 m) | 0.34 ± 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.50 | 5 | 0.35 ± 0.10 | 0.22 | 0.48 | 9 | 0.00 | -0.15-0.15 | 0.995 | 1.000 |

| QALY (EQ5D 0-12 m) | 0.64 ± 0.42 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 4 | 0.66 ± 0.23 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 7 | 0.01 | -0.38-0.47 | 0.949 | 0.927 |

| QALY (EQVAS 0-6 m) | 0.36 ± 0.09 | 0.24 | 0.46 | 5 | 0.32 ± 0.09 | 0.22 | 0.45 | 9 | -0.04 | -0.14-0.05 | 0.385 | 0.364 |

| QALY (EQVAS 0-12 m) | 0.73 ± 0.20 | 0.49 | 0.92 | 4 | 0.67 ± 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.94 | 7 | -0.07 | -0.29-0.18 | 0.602 | 0.648 |

| Number of additional procedures (0-6 m) | 0.80 ± 1.10 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 5 | 3.22 ± 2.91 | 0.00 | 8.00 | 9 | 2.42 | 0.127 | ||

| Number of endoscopic procedures (0-6 m) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.33 ± 0.71 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 9 | 0.33 | 0.505 | ||

| Number of balloon procedures (0-6 m) | 0.40 ± 0.55 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5 | 1.22 ± 1.39 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 9 | 0.82 | 0.275 | ||

| Number of endoscopies (0-6 m) | 0.40 ± 0.55 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5 | 1.67 ± 1.50 | 0.00 | 4.00 | 9 | 1.27 | 0.107 | ||

| Number of additional procedures (0-12 m) | 1.20 ± 0.84 | 0.00 | 2.00 | 5 | 4.13 ± 3.87 | 0.00 | 10.0 | 8 | 2.93 | 0.165 | ||

| Number of endoscopic procedures (0-12 m) | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5 | 0.63 ± 1.06 | 0.00 | 3.00 | 8 | 0.63 | 0.417 | ||

| Number of balloon procedures (0-12 m) | 0.40 ± 0.55 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5 | 1.38 ± 1.77 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 8 | 0.98 | 0.385 | ||

| Number of endoscopies (0-12 m) | 0.80 ± 0.45 | 0.00 | 1.00 | 5 | 2.13 ± 1.89 | 0.00 | 5.00 | 8 | 1.33 | 0.203 | ||

Sensitivity analyses explored the impact upon dysphagia using repeated measures ANCOVA, adjusting for baseline dysphagia and hospital site. Additionally, missing values were imputed (one value at 6 mo and four values at 12 mo) and mean dysphagia scores and repeated measure estimates were produced for the imputation dataset. Qualitatively, findings were similar for a range of sensitivity analyses of the primary endpoint with a statistically significant or borderline significant average increase in dysphagia score of about 1 point for patients receiving a stent (Table 4).

| Mean difference | 95%CI | P value1 | P value2 | |

| Repeated measures ANOVA | ||||

| Dysphagia score (3, 6 m) | 1.17 | (0.21-2.13) | 0.022 | |

| Dysphagia score (3, 6, 12 m) | 1.10 | (-0.11-2.31) | 0.070 | |

| Repeated measures ANOVA (imputed) | ||||

| Dysphagia score (3, 6 m) | 1.13 | (-0.05-2.32) | 0.058 | |

| Dysphagia score (3, 6, 12 m) | 1.01 | (-0.30-2.32) | 0.113 | |

| Dysphagia score (imputed) | ||||

| Dysphagia score (Average 3 and 6 m) | 0.94 | (0.18-1.70) | 0.015 | 0.021 |

| Dysphagia score (Average 3, 6 and 12 m) | 0.93 | (0.06-1.79) | 0.036 | 0.025 |

| Dysphagia score (AUC 0-6 m) | 0.38 | (0.03-0.73) | 0.032 | 0.075 |

| Dysphagia score (AUC 0-12 m) | 0.83 | (0.07-1.58) | 0.033 | 0.024 |

Quality of life (QALY) estimates were similar for BS and ED patients regardless of estimation by EQ-5D or EQ-VAS, or 6 mo or 12 mo follow up. Similarly, there were no differences in the number of post-intervention additional endoscopic procedures. However a consistent, non-significant, pattern of greater intervention was noted in the BS group (Table 3).

Adverse events were more common in patients receiving a stent: in total (mean/patient: BS 4.9, ED 1.0; P = 0.01); assessed as related to intervention (possibly, probably, definitely) (mean/patient: BS 1.4, ED 0; P = 0.024); and assessed as severe (mean/patient: BS 1.8, ED 0; P = 0.026) (MWU). Numbers of patients reporting adverse events by type are tabulated (Table 5).

| Adverse event1 | Endoscopic balloon dilatation (n = 9) | Biodegradable stent (n = 6) | ||

| Unrelated | Related | Unrelated | Related | |

| Abdominal pain | 2 | 1 (1) | ||

| Acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis | 1 | |||

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | |||

| Alcohol withdrawal syndrome | 1 (1) | |||

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 | |||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 1 | |||

| Constipation | 1 | |||

| Cough | 1 | |||

| Diverticulosis | 1 | |||

| Dry mouth | 1 | |||

| Dysphagia | 1 | 1 | 6 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Dyspnoea | 1 | |||

| Eye infection - Left eye | 1 | |||

| Foul taste in mouth | 1 | |||

| Fractured rib | 1 (1) | |||

| Gastro-oesophageal reflux | 1 | |||

| Haematemesis | 2 | 1 | ||

| Hiccups | 1 | |||

| Hyperglycemia | 1 (1) | 1 | ||

| Hypertension | 1 | |||

| Hypotension | 1 (1) | |||

| Insomnia | 1 | |||

| Oesophageal candidiasis | 1 | |||

| Oesophageal spasm | 1 | |||

| Pain | 2 (1) | 1 | ||

| Positive Faecal occult blood test | 1 | |||

| Pruritus - Lower legs (right and left) | 1 (1) | |||

| Retrosternal pain | 1 | |||

| Vitamin B deficiency | 1 | |||

| Vomiting | 1 | |||

Concomitant use of gastrointestinal prescribed medication was greater in the stent group (mean/patient: BS 5.1, ED 2.0 prescriptions; P < 0.001) (MWU). Numbers of patients using concomitant medications by symptom are tabulated (Table 6).

| Endoscopic balloon dilatation (n = 9) | Biodegradable stent (n = 6) | |

| Bowel management | ||

| Loperamide | 1 | 0 |

| Constipation | ||

| Laxative | 1 | 2 |

| Haematemesis | ||

| Metoclopramide | 0 | 1 |

| Heartburn | ||

| Alginate | 0 | 1 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 1 | 4 |

| Cyclizine | 0 | 3 |

| Domperidone | 0 | 2 |

| Metoclopramide | 1 | 4 |

| Nutritional deficit | ||

| Nutritional Supplement | 1 | 4 |

| Oesophageal candidiasis | ||

| Antifungal | 0 | 1 |

| Symptoms of BOS/reflux disease | 6 | 9 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 5 | 9 |

| H2-receptor antagonist | 1 | 2 |

| Sucralfate | 0 | 1 |

This pilot study is the first randomised controlled trial comparing biodegradable stent and balloon dilatation for benign oesophageal stricture. Although the trial findings are diminished by under-recruitment, the randomised comparison remains valid and does not support the use of biodegradable stents. Stenting was associated with greater dysphagia, co-medication and adverse events. This may have occurred in part because of chance atypical low dysphagia follow-up scores in the balloon dilatation group, causing biodegradable stents to perform poorly by comparison. However, dysphagia and other baseline characteristics were similar between groups at baseline, validating the comparison.

This study aimed to recruit 50 patients at 6 centres across the North East of England. From the outset there were issues with under-recruitment; a potential explanation might be the steady increase in the use of proton pump inhibitors in primary care since the publication in England of the NICE Guidelines for management of Dyspepsia in Adults[16], thought to have contributed to a reduction in oesophageal strictures[17,18]. Recruitment was closed after 17 patients were recruited with no prospect of reaching the target within a reasonable time-scale. Subsequently the primary endpoint of average dysphagia score over 12 mo was altered to 6 mo to increase the number of completed scores. Due to low recruitment, the trial was kept open to recruitment for longer than originally anticipated. Imputation of missing values was used to support the primary analysis, which used complete-patient data. The change of time-frame did not impact qualitatively on the findings.

It might appear counterintuitive that an intervention to restore oesophageal topology might fail to improve dysphagia when compared to (transient) balloon dilatation. However the oesophageal tract has somatic sensitivity and the process of the stent dissolving, possibly unevenly, might promote discomfort or reflux. Biodegradable stents lose their radial force over time as they degrade and may cause stent-induced mucosal or parenchymal injury. Findings from this pilot trial are qualitatively consistent with positive case reports and series reported in the literature, since stent group symptom scores similarly improved over time. Given the possibility of regression to mean (patients treated at an acute point tending to improve over time), the findings underline the need for a rigorously conducted and adequately powered trial before widespread adoption of this technology. Validated measures of patient experience should be incorporated. Findings also highlight the need to demonstrate organizational, clinical and patient support in achieving recruitment. Given the cost of biodegradable stents (the stent cost excluding placement was £900/patient within the study), cost-effectiveness analysis should be included within such a trial.

The academic team would like to acknowledge the significant input of the research nurses and teams at each site and the administrative team within Durham Clinical Trials Unit.

Benign oesophageal strictures are managed by endoscopic dilatation using balloons or bougies, often requiring repeat procedures with their associated risks and costs and discomfort to patients. Biodegradable stents do not usually require removal and may reduce the need for repeated endoscopy.

No randomized controlled trials comparing biodegradable stents with other stents or with balloon dilatation have been identified. Lack of adequately robust evidence for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness formed the rationale of this trial.

This pilot multi-site randomized study demonstrated that stenting was associated with greater dysphagia, co-medication and adverse events. Groups were comparable at baseline and findings are statistically significant but patient numbers are small.

The oesophageal tract has somatic sensitivity and the process of the stent dissolving, possibly unevenly, might promote discomfort or reflux. Rigorously conducted and adequately powered trials are needed before widespread adoption of this technology.

Benign oesophageal stricture: Narrowing of the oesophagus is often caused by injury or radiation which leads to difficulty swallowing; Biodegradable stent: A hollow structure placed into the oesophagus which gradually dissolves; Endoscopic dilatation: A procedure conducted under anaesthesia to stretch the oesophagus, usually by means of an endoscopic balloon.

This is a good research idea as it is an important clinical entity. This is a nice pilot study that compares biodegradable stents and balloon dilatation. It is a well-designed study that unfortunately was not completed due to lack of included patients.

P- Reviewer: Homan M, Shehata MMM S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Jung KW, Gundersen N, Kopacova J, Arora AS, Romero Y, Katzka D, Francis D, Schreiber J, Dierkhising RA, Talley NJ. Occurrence of and risk factors for complications after endoscopic dilation in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swarbrick ET, Gough AL, Foster CS, Christian J, Garrett AD, Langworthy CH. Prevention of recurrence of oesophageal stricture, a comparison of lansoprazole and high-dose ranitidine. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:431-438. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Broor SL, Kumar A, Chari ST, Singal A, Misra SP, Kumar N, Sarin SK, Vij JC. Corrosive oesophageal strictures following acid ingestion: clinical profile and results of endoscopic dilatation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1989;4:55-61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Isolauri J, Nordback I, Markkula H. Surgery for reflux stricture of the oesophagus. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1989;78:120-123. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Moghissi K, Goebells P. Relevance of anatomopathology of high oesophageal strictures to the design of surgical treatment. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1990;4:91-95; discussion 96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bonavina L, Segalin A, Fumagalli U, Peracchia A. Surgical management of benign stricture from reflux oesophagitis. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1995;84:175-178. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moghissi K, Pender D. Management of proximal oesophageal stricture. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1989;3:93-7; discussion 97-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Straumann A, Bussmann C, Zuber M, Vannini S, Simon HU, Schoepfer A. Eosinophilic esophagitis: analysis of food impaction and perforation in 251 adolescent and adult patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:598-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Canena JM, Liberato MJ, Rio-Tinto RA, Pinto-Marques PM, Romão CM, Coutinho AV, Neves BA, Santos-Silva MF. A comparison of the temporary placement of 3 different self-expanding stents for the treatment of refractory benign esophageal strictures: a prospective multicentre study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van Halsema EE, Wong Kee Song LM, Baron TH, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP, Ginsberg GG, Shah PM, Fleischer DE, Ratuapli SK, Fockens P. Safety of endoscopic removal of self-expandable stents after treatment of benign esophageal diseases. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dua KS, Vleggaar FP, Santharam R, Siersema PD. Removable self-expanding plastic esophageal stent as a continuous, non-permanent dilator in treating refractory benign esophageal strictures: a prospective two-center study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2988-2994. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Hirdes MM, Siersema PD, Vleggaar FP. A new fully covered metal stent for the treatment of benign and malignant dysphagia: a prospective follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:712-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Siersema PD. Stenting for benign esophageal strictures. Endoscopy. 2009;41:363-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hindy P, Hong J, Lam-Tsai Y, Gress F. A comprehensive review of esophageal stents. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2012;8:526-534. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Lorenzo-Zúñiga V, Moreno-de-Vega V, Marín I, Boix J. Biodegradable stents in gastrointestinal endoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:2212-2217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mason JM, Delaney B, Moayyedi P, Thomas M, Walt R. Managing dyspepsia without alarm signs in primary care: new national guidance for England and Wales. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1135-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, Ross BA, Bate CM, Brown P, Dronfield MW, Green JR, Hislop WS, Theodossi A. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Restore Investigator Group. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1312-1318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo J, Koehler RE, Spenney JG, Mills TP, Champion G. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:907-915. [PubMed] |