Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17626

Revised: January 21, 2014

Accepted: June 14, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 356 Days and 17.9 Hours

AIM: To investigate the comparative effect of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in elderly patients.

METHODS: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has induced a revolution in the treatment of gallbladder disease. Nevertheless, surgeons have been reluctant to implement the concepts of minimally invasive surgery in older patients. A systematic review of Medline was embarked on, up to June 2013. Studies which provided outcome data on patients aged 65 years or older, subjected to laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy were considered. Mortality, morbidity, cardiac and pulmonary complications were the outcome measures of treatment effect. The methodological quality of selected studies was appraised using valid assessment tools. Τhe random-effects model was applied to synthesize outcome data.

RESULTS: Out of a total of 337 records, thirteen articles (2 randomized and 11 observational studies) reporting on the outcome of 101559 patients (48195 in the laparoscopic and 53364 in the open treatment group, respectively) were identified. Odds ratios (OR) were constantly in favor of laparoscopic surgery, in terms of mortality (1.0% vs 4.4%, OR = 0.24, 95%CI: 0.17-0.35, P < 0.00001), morbidity (11.5% vs 21.3%, OR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.33-0.59, P < 0.00001), cardiac (0.6% vs 1.2%, OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.38-0.80, P = 0.002) and respiratory complications (2.8% vs 5.0%, OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.51-0.60, P < 0.00001). Critical analysis of solid study data, demonstrated a trend towards improved outcomes for the laparoscopic concept, when adjusted for age and co-morbid diseases.

CONCLUSION: Further high-quality evidence is necessary to draw definite conclusions, although best-available evidence supports the selective use of laparoscopy in this patient population.

Core tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis investigates the comparative effect of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in elderly patients. Critical analysis of solid study data, demonstrated a trend towards improved outcomes for the laparoscopic concept, when adjusted for age and co-morbid diseases. Current data do not definitively support the use of laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy on older patients. Further high-quality evidence is necessary to draw definite conclusions, although best-available evidence supports the elective use of laparoscopy in this patient population.

-

Citation: Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA, Koch OO, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic

vs open cholecystectomy in elderly patients. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17626-17634 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17626.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17626

Laparoscopic surgery has induced a tremendous revolution in the treatment of gallbladder disease. Surgery has been traditionally considered the last therapeutic resort for symptomatic cholelithiasis before the advent of laparoscopy, whereas lithotripsy and cholecystostomy have been commonly favored as less invasive alternatives[1]. In the era of minimally invasive surgery, indications for surgery have become more liberal, resulting in an enormous rise in the number of laparoscopic cholecystectomies performed annually[2]. The laparoscopic procedure has been shown to offer the advantages of decreased pain, shorter convalescence, reduced operative stress and limited inflammatory response[3].

Despite these merits, the surgical community has been reluctant to implement the laparoscopic approach in the elderly population. Data from population-based studies suggest that 21% to 55% of geriatric patients in the United States are still subjected to open cholecystectomy[4-7]. These figures largely derive from as-treated analyses, however they reflect a defensive operative position against this patient population, which commonly presents with acute or chronic recurrent cholecystitis, gallbladder empyema or hydrops. Although the role of laparoscopy in the treatment of a wide spectrum of gallbladder pathology has been well established[8,9], this conservative surgical trend suggest that the outcomes of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the geriatric patient population have been inadequately defined.

The present paper is a systematic review of current literature, aiming at identifying comparative evidence between laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy in the elderly. Operative results are approached statistically, using valid meta-analytical models. A critical discussion of results attempts to determine the strengths and limitations of available data, in order to evaluate the quality of evidence and identify areas of future research.

Two investigators established the study protocol, which defined the objectives of the study, the search and abstracting design, inclusion and exclusion criteria and methodology of analysis. The protocol conformed to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses statement[10], and the Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines[11]. This study is part of a project investigating the comparative effect of various laparoscopic procedures in geriatric patients.

Prospective and retrospective studies which provided outcome data on patients aged 65 years or older, who were subjected to either laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy were considered for inclusion. Studies reporting on at least one of the outcome measures were included. Articles not containing distinct data for patients 65 years or older, or not reporting on any of the outcome measures were discarded.

Mortality was the primary outcome measure of treatment effect. Secondary outcome measures included cardiac complications, pulmonary complications, and overall morbidity.

The literature search was performed in collaboration with a clinical librarian. The database of the National Library of Medicine (Medline, provider PubMed) was searched without date restrictions. Limits were applied with regard to age (65+ years), language (English, German), and text availability (abstract available). The terms laparoscopy, laparotomy, open, conventional, aged, elderly, older, sexagenarian, septuagenarian, octogenarian, nonagenarian, postoperative complication, morbidity, death, and mortality were combined using the Boolean operators AND or OR. The search strategy protocol is available upon request. Date of the last screening was June 11, 2013. Titles and abstracts were scrutinized to identify potentially eligible articles. The full texts of studies considered to contain data predetermined by the protocol were obtained. First-level and second level screening was performed by two independent authors in an unblinded manner (Antoniou SA, Antoniou GA). Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

An electronic database based on the Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group’s data extraction template was pilot-tested on the three most recent studies and refined accordingly. Data were collected on study characteristics, name of first author, year of publication, patient recruitment period, study design, total number of patients, number of patients in the laparoscopic and the open arm, age limit, mean or median age of the study population, standard deviation or range, method of analysis (intention to treat/as treated) and the outcome measures as outlined above. Cardiac complications were considered the following: myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia, arrhythmia, cardiac failure, or the terms “cardiovascular complications or morbidity”. Respiratory complications were considered atelectasia, pneumonia, adult respiratory distress syndrome, pleural effusion, or the terms “respiratory or pulmonary failure”, “respiratory or pulmonary insufficiency”, or “pulmonary morbidity”.

Randomized trials were subjected to methodological quality assessment according to the Cochrane Collaboration’s Tool for assessing risk of bias[12]. This tool considers the sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors, inadequately reported or missing outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other potential threats to validity.

The quality of observational studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale (NOS) for case control studies or cohort studies (as applicable)[13]. This tool evaluates three main methodological elements of case-control studies: selection methods (adequate case definition, representativeness of the cases, appropriate selection and definition of controls), comparability of cases and controls on the basis of the design or analysis, and assessment of exposure (ascertainment of exposure, non-response rate). The scale uses a star system, with a maximum of nine stars; studies achieving ≥ 6 stars were considered to be of higher quality.

Individual study odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CI were calculated from event numbers extracted from each study before data pooling. In calculation of the OR, the total number of patients assigned in each group was used as the denominator. Summary estimates of ORs were obtained with a random effects model according to DerSimonian and Laird[14]. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, a method expressing the percentage of variation across studies. I2 values between 0% and 25% suggest low level, values above 25% suggest moderate level, and values above 75% suggest high level of heterogeneity. Publication bias was assessed visually evaluating the symmetry of funnel plots. Statistical analysis was performed using RevMan (Review Manager 5.2, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Statistical expertise was available and it was provided by one of the study authors (Antoniou GA).

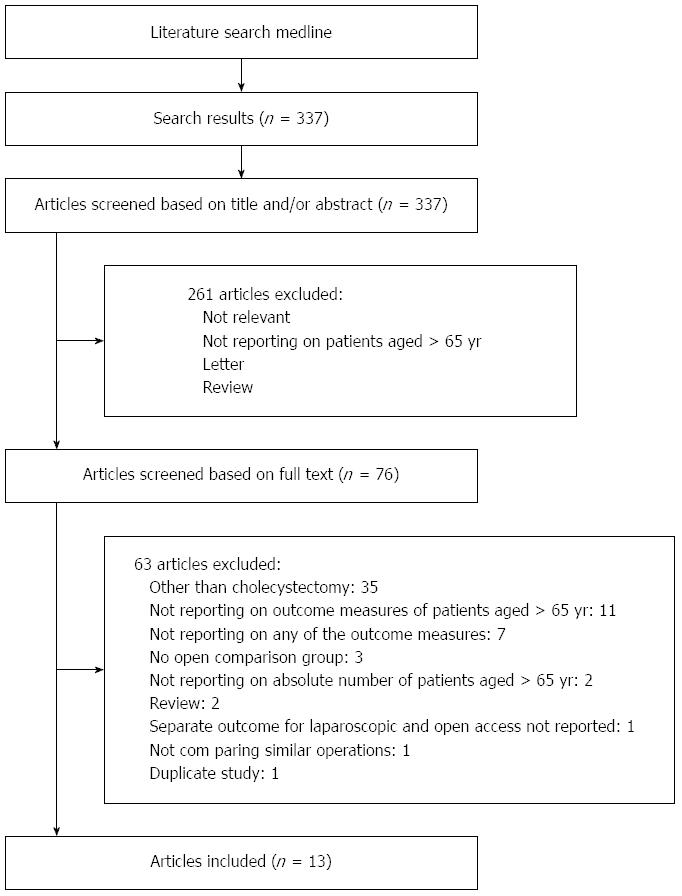

A total of 337 records were identified by the primary search of the electronic database. The first level screening identified 76 potentially eligible articles. Full text review excluded 63 articles. Thirteen articles fulfilled the selection criteria and were included in the analysis[4-7,15-23]. Figure 1 summarizes the search history.

Two randomized studies and 11 observational studies were identified (Table 1). The study population consisted of 101559 patients; 48195 in the laparoscopic treatment group and 53364 in the open treatment group. Eleven articles reported on mortality rates, 10 reported on overall morbidity, 6 reported on cardiac complications and 8 reported on respiratory complications (Table 2). The two randomized trials were of poor quality, because they did not provide adequate information to permit judgment on any of the quality parameters (quality assessment of randomized trials available upon request). Only one observational study achieved a NOS score of 6 or more; sensitivity analysis of quality reports could thus not be undertaken. Age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score and/or cardiopulmonary co-morbidities were similar in both treatment arms in 3 studies only; a planned sensitivity analysis including these data was thus not performed.

| Ref. | Year | Study design | Period | Patients (n) (lap/open) | Age | Investigated outcomes | ITT/AT | NOS |

| Massie et al[15] | 1993 | Retrospective | 1990-1991 | 58 | > 70 | Morbidity | NR | 3 |

| (33/25) | ||||||||

| Feldman et al[4] | 1994 | Prospective database1 | 1988-1992 | 2269 | > 65 | Mortality | NR | 4 |

| (1508/761) | ||||||||

| Lucier et al[5] | 1995 | Prospective database2 | 1991-1992 | 3907 | > 65 (mean 73.9 lap, 75.4 open) | Morbidity, mortality, cardiac, respiratory | NR | 3 |

| (1769/2138) | ||||||||

| Samkoff et al[6] | 1995 | Prospective database3 | 1992-1993 | 63920 | > 65 | Morbidity, mortality, respiratory | NR | 3 |

| (29731/34189) | ||||||||

| Huang et al[16] | 1996 | RCT | 1992-1993 | 27 | > 70 | Morbidity, mortality, cardiac, respiratory | NA | NA |

| (15/12) | ||||||||

| Lujan et al[17] | 1998 | RCT | 1991-1996 | 264 | > 65 [median 71 (65-87) lap, 72 (65-88) open] | Morbidity, mortality, respiratory | NR | NA |

| (133/131) | ||||||||

| Maxwell et al[18] | 1998 | Prospective database4 | 1988-1992 | 18500 | > 80 (mean, 83.9 lap, 84.0 open) | Mortality | NR | 4 |

| (5034/13466) | ||||||||

| Pessaux et al[19] | 2001 | Prospective | 1992-1999 | 139 | > 75 [mean 81.9 (75-98) lap, 81.9 (75-93) open] | Morbidity, mortality, cardiac, respiratory | NR | 7 |

| (50/89) | ||||||||

| Fisichella et al[20] | 2002 | Retrospective | 1995-1998 | 35 | > 70 (mean 74 ± 2.4 lap, 74 ± 4.1 open) | Morbidity, mortality, cardiac, respiratory | ITT | 4 |

| (24/11) | ||||||||

| Chau et al[21] | 2002 | Retrospective | 1994-1999 | 73 | > 75 (mean 79.2 ± 4.2 lap, 80.7 ± 4.6 open) | Morbidity, mortality, cardiac, respiratory | ITT | 5 |

| (31/42) | ||||||||

| Moyson et al[22] | 2008 | Retrospective | 1991-2007 | 100 | > 75 [median 83 (75-94)] | Mortality, morbidity | AT | 5 |

| (85/15) | ||||||||

| Leardi et al[23] | 2009 | Retrospective | 2000-2006 | 341 | > 70 | Morbidity | NR | 4 |

| (258/83) | ||||||||

| Tucker et al[7] | 2011 | Prospective database5 | 2005-2008 | 11926 | > 65 [median 73.0 (69-79)] | Mortality, morbidity, cardiac, respiratory | AT | 4 |

| (9524/2402) |

| Ref. | Conversion | Mortality | Morbidity | Cardiac | Respiratory |

| Massie et al[15] | NR | NR | 4/33 lap | NR | NR |

| 19/66 open | |||||

| Feldman et al[4] | NR | 7/1508 lap | NR | NR | NR |

| 11/761 open | |||||

| Lucier et al[5] | NR | 16/1769 lap | 200/1769 lap | 17/1769 lap | 25/1769 lap |

| 116/2138 open | 354/2138 open | 26/2138 open | 64/2138 open | ||

| Samkoff et al[6] | NR | 252/29731 lap | 3428/29731 lap | NR | 871/29731 lap |

| 1523/34189 open | 7361/34189 open | 1751/34189 open | |||

| Huang et al[16] | 0 /15 | 0/15 lap | 0/15 lap | 0/15 lap | 0/15 lap |

| (0%) | 0/12 open | 3/12 open | 0/12 open | 1/12 open | |

| Lujan et al[17] | 11/113 | 0/133 lap | 18/133 lap | NR | 0/133 lap |

| (9.7%) | 1/131 open | 29/131 open | 5/131 open | ||

| Maxwell et al[18] | NR | 91/5034 lap | NR | NR | NR |

| 593/13466 open | |||||

| Pessaux[19] | 16/50 | 0/50 lap | 9/50 lap | 0/50 lap | 1/50 lap |

| (32%) | 4/89 open | 19/89 open | 2/89 lap | 2/89 open | |

| Fisichella et al[20] | 2/24 | 0/24 lap | 3/24 lap | 0/24 lap | 0/24 lap |

| (8.3%) | 0/11 open | 6/11 open | 0/11 open | 0/11 open | |

| Chau et al[21] | 11/31 | 0/31 lap | 4/31 lap | 0/31 lap | 1/31 lap |

| (35.5%) | 3/42 open | 17/42 open | 4/42 open | 6/42 open | |

| Moyson et al[22] | 12/85 | 3/73 lap | 19/73 lap | NR | NR |

| (14.1%) | 5/27 open | 14/15 open | |||

| Leardi et al[23] | 16/158 (10.1%) | NR | 12/258 lap | NR | NR |

| 14/83 open | |||||

| Tucker et al[7] | 728/9529 (7.6%) | 67/9524 lap | NR | 48/9524 lap | 76/9524 lap |

| 65/2402 open | 26/2402 open | 87/2402 open |

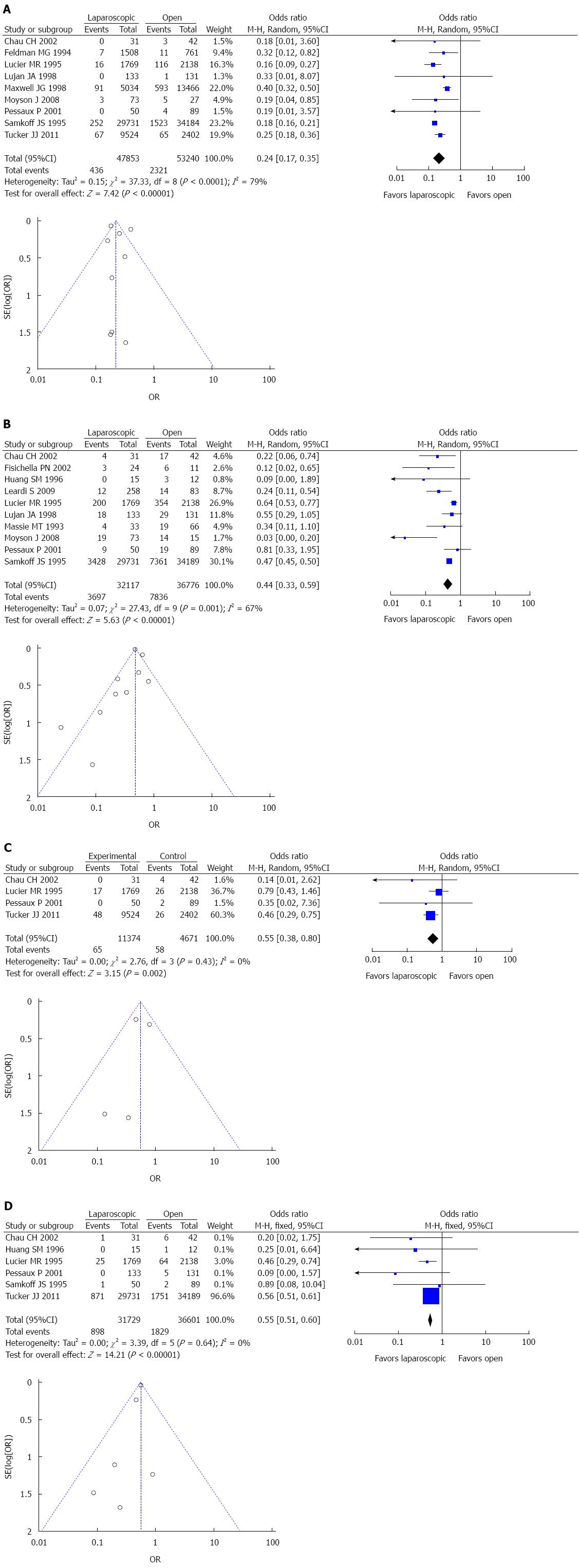

Mortality was 1.0% for the laparoscopic approach and 4.4% for the open approach (OR = 0.24, 95%CI: 0.17-0.35, P < 0.00001). High level of heterogeneity (I2 = 79%) and publication bias was evident (Figures 2A).

Morbidity rates were 11.5% and 21.3%, respectively (OR = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.33-0.59, P < 0.00001). Moderate heterogeneity existed (I2 = 67%), and strong evidence of publication bias (Figure 2B).

Cardiac complications occurred in 0.6% and 1.2% of the laparoscopic and the open patient population, respectively (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.38-0.80, P = 0.002). Heterogeneity across studies was not evident (I2 = 0%) and the possibility for publication bias was low (Figures 2C).

Respiratory complications were registered in 2.8% and 5.0% of the laparoscopic and the open treatment arm, respectively (OR = 0.55, 95%CI: 0.51-0.60, P < 0.00001). There was no evidence of heterogeneity across studies (I2 = 0%) or publication bias (Figure 2D).

Comparative evidence on the application of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients is not adequately robust to support or refute its routine use, according to analysis of currently available evidence. Although the effect sizes are indicative of a benefit for the laparoscopic approach, there are several shortcomings of the provided data, which need to be taken into account, before definite conclusions can be reached.

A significant limitation is introduced by the variety of criteria for inclusion among reports. Although eight of 13 studies predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, which provides some homogeneity of the study population, selection bias regarding the stage of acute cholecystitis, the presence of sepsis, and co-morbid diseases cannot be eliminated. The open surgical approached may thus have been preferred more often in cases of complicated gallbladder disease or in the presence of significant co-morbidity. The spectrum of inclusion criteria and surgical trends is reflected in the moderate-to-high level of heterogeneity of the variables mortality and morbidity. Morbidity data from two available randomized studies, which provide homogeneity of patients and randomization of procedures, were in favor of laparoscopic cholecystectomy[16,17]. Acute cholecystitis as inclusion criterion provided relative homogeneity of the study populations of three studies[19,21,22], which all favored the laparoscopic approach. Similarly, when symptomatic cholecystolithiasis was considered as inclusion criterion, the results favored laparoscopic cholecystectomy[16,17,20].

The majority of studies were of poor methodological quality, which may bias the results in favor of either approach. The study by Pessaux et al[19] was of high methodological quality, achieving seven of 8 NOS stars. The authors prospectively included 139 patients with acute cholecystitis over a 7-year period. They found a constant trend in favor of the laparoscopic arm considering the outcome measures of this analysis, although statistical significance was not reached. Three studies, which included patients with similar ASA score and/or cardiopulmonary disease[16,19,21], all demonstrated reduced mortality, morbidity, and incidence of cardiac and respiratory complications.

Opposite to the above limitations of this analysis, its strengths allow for a rational interpretation of the results. The large number of patients, the variety of reports and the time of publication, ranging from the early years of laparoscopic cholecystectomy until recently, allow multifaceted representation of surgical trends. Based on the present published and anecdotal data, it cannot be overstated, that open surgery is being a persisting surgical practice in acute biliary operations of the geriatric patient population. Emerging evidence suggests decreased inflammatory response both in acute and elective laparoscopic cases as compared to open surgery[24-26], which might adversely affect pulmonary function[27]. This association becomes more important in the elderly, where functional reserves are decreased, and frequent co-morbidities make postoperative rehabilitation more complex[28].

The role of percutaneous cholecystostomy in poor operative candidates may not be disregarded. With this treatment option, both life expectancy and co-morbid diseases need to be taken into account, because definite surgical treatment due to recurrent disease is necessary in a significant proportion of these patients[29,30], whereas subsequent laparoscopic cholecystectomy is accompanied by acceptable technical success[31,32], although difficulties may be encountered due to distorted anatomy.

The development of an evidence-based treatment protocol which considers factors as patient’s age, co-morbidities, the present of complicated gallbladder disease and previous operations is considered essential. Current data are inadequate to support routine use of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients, although best available evidence demonstrates a constant trend in favor of the laparoscopic approach in terms of mortality, morbidity, cardiac and respiratory complications in selected cases.

The authors are grateful to Ms. Aggeliki Zachou, clinical librarian, for her kind and continuous support.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has been established as the gold standard therapy for gallbladder disease. Population-based data suggest that elderly patients are more frequently subjected to open than laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The comparative treatment effect of these two approaches in elderly patients has been inadequately defined.

Minimally invasive treatment modalities, such as percutaneous cholecystostomy and lithotripsy or definite surgical therapy by means of open cholecystectomy appear to be preferred by a significant proportion of surgeons. The well-defined beneficial comparative effects of laparoscopic over open surgery, such as minimization of trauma and inflammatory response, shorter convalescence and reduced respiratory compromise, may apply stronger to this frail patient population.

Early clinical evidence has suggested positive results for elderly patients in a variety of laparoscopic procedures. These data are fragmentary and mostly lack significant power. Due to the low morbidity and mortality of laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy, significant differences in treatment effects are often not detected. Cardiac and pulmonary morbidity are of paramount importance in elderly patients; the low incidence of these complications may result in underestimation of their association with the laparoscopic or the open treatment. Furthermore, concerns have been raised regarding the effect of pneumoperitoneum in elderly patients.

Best available evidence suggests lower mortality, overall morbidity, cardiac and pulmonary complications in elderly patients subjected to laparoscopic as compared to open cholecystectomy. For the application of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly patients, co-existing factors, such as co-morbidities, the presence of complicated gallbladder disease and previous operations need to be taken into account.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The surgical procedure of removing the gallbladder by laparoscopy, that is, application of pneumoperitoneum and introduction of special instruments into the abdomen; pneumoperitoneum: Refers to the application of CO2 gas into the peritoneal cavity, in order to perform a laparoscopic procedure.

This is a generally well-written, scientifically sound and well-researched article. It includes a large number of patients in the included articles.

P- Reviewer: Chiu CC, Rangarajan M S- Editor: Gou SX L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu XM

| 1. | Glenn F. Trends in surgical treatment of calculous disease of the biliary tract. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:877-884. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Gallstones and laparoscopic cholecystectomy. NIH Consens Statement. 1992;10:1-28. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Kuhry E, Jeekel J, Bonjer HJ. Effect of laparoscopy on the immune system. Semin Laparosc Surg. 2004;11:37-44. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Feldman MG, Russell JC, Lynch JT, Mattie A. Comparison of mortality rates for open and closed cholecystectomy in the elderly: Connecticut statewide survey. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1994;4:165-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lucier MR, Lee K. Trends in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Indiana. Indiana Med. 1995;88:200-204. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Samkoff JS, Wu B. Laparoscopic and open cholecystectomy outcomes in Medicare beneficiaries in member states of the Large State PRO Consortium. Am J Med Qual. 1995;10:183-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tucker JJ, Yanagawa F, Grim R, Bell T, Ahuja V. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is safe but underused in the elderly. Am Surg. 2011;77:1014-1020. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, Fanelli R. SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2368-2386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Miura F, Takada T, Strasberg SM, Solomkin JS, Pitt HA, Gouma DJ, Garden OJ, Büchler MW, Yoshida M, Mayumi T. TG13 flowchart for the management of acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2013;20:47-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 184] [Cited by in RCA: 192] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, Clarke M, Devereaux PJ, Kleijnen J, Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13930] [Cited by in RCA: 13347] [Article Influence: 834.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, Moher D, Becker BJ, Sipe TA, Thacker SB. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008-2012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14425] [Cited by in RCA: 16793] [Article Influence: 671.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Higgins JP, Altman DG. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2009; 187-235. |

| 13. | Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses [Ottawa Hospital/Research Institute web site]. Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. Accessed June 11, 2013. |

| 14. | DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177-188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26739] [Cited by in RCA: 30408] [Article Influence: 779.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Massie MT, Massie LB, Marrangoni AG, D’Amico FJ, Sell HW. Advantages of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the elderly and in patients with high ASA classifications. J Laparoendosc Surg. 1993;3:467-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Huang SM, Wu CW, Lui WY, P’eng FK. A prospective randomised study of laparoscopic v. open cholecystectomy in aged patients with cholecystolithiasis. S Afr J Surg. 1996;34:177-179; discussion 179-180. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Lujan JA, Sanchez-Bueno F, Parrilla P, Robles R, Torralba JA, Gonzalez-Costea R. Laparoscopic vs. open cholecystectomy in patients aged 65 and older. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1998;8:208-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Maxwell JG, Tyler BA, Rutledge R, Brinker CC, Maxwell BG, Covington DL. Cholecystectomy in patients aged 80 and older. Am J Surg. 1998;176:627-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Pessaux P, Regenet N, Tuech JJ, Rouge C, Bergamaschi R, Arnaud JP. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy: a prospective comparative study in the elderly with acute cholecystitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2001;11:252-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Fisichella PM, Di Stefano A, Di Carlo I, La Greca G, Russello D, Latteri F. Efficacy and safety of elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy in elderly: a case-controlled comparison with the open approach. Ann Ital Chir. 2002;73:149-153; discussion 153-154. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Chau CH, Tang CN, Siu WT, Ha JP, Li MK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus open cholecystectomy in elderly patients with acute cholecystitis: retrospective study. Hong Kong Med J. 2002;8:394-399. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Moyson J, Thill V, Simoens Ch, Smets D, Debergh N, Mendes da Costa P. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis in the elderly: a retrospective study of 100 patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2008;55:1975-1980. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Leardi S, De Vita F, Pietroletti R, Simi M. Cholecystectomy for gallbladder disease in elderly aged 80 years and over. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56:303-306. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Karayiannakis AJ, Makri GG, Mantzioka A, Karousos D, Karatzas G. Systemic stress response after laparoscopic or open cholecystectomy: a randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1997;84:467-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang G, Jiang Z, Zhao K, Li G, Liu F, Pan H, Li J. Immunologic response after laparoscopic colon cancer operation within an enhanced recovery program. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1379-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Schietroma M, Piccione F, Carlei F, Clementi M, Bianchi Z, de Vita F, Amicucci G. Peritonitis from perforated appendicitis: stress response after laparoscopic or open treatment. Am Surg. 2012;78:582-590. [PubMed] |

| 27. | O’Mahony DS, Glavan BJ, Holden TD, Fong C, Black RA, Rona G, Tejera P, Christiani DC, Wurfel MM. Inflammation and immune-related candidate gene associations with acute lung injury susceptibility and severity: a validation study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Evers BM, Townsend CM, Thompson JC. Organ physiology of aging. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74:23-39. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Howard JM, Hanly AM, Keogan M, Ryan M, Reynolds JV. Percutaneous cholecystostomy--a safe option in the management of acute biliary sepsis in the elderly. Int J Surg. 2009;7:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nikfarjam M, Shen L, Fink MA, Muralidharan V, Starkey G, Jones RM, Christophi C. Percutaneous cholecystostomy for treatment of acute cholecystitis in the era of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2013;23:474-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Vázquez Tarragón A, Azagra Soria JS, Lens V, Manzoni D, Fabiano P, Goergen M. Two staged minimally invasive treatment for acute cholecystitis in high risk patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2013;60:466-469. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Paran H, Zissin R, Rosenberg E, Griton I, Kots E, Gutman M. Prospective evaluation of patients with acute cholecystitis treated with percutaneous cholecystostomy and interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Int J Surg. 2006;4:101-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |