Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17532

Revised: May 12, 2014

Accepted: July 15, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 310 Days and 14.6 Hours

AIM: To assess the prognostic significance of cathepsin L, a cysteine protease that degrades the peri-tumoral tissue, in patients with pancreatic cancer.

METHODS: Plasma samples from 127 pancreatic cancer patients were analyzed for cathepsin L levels by ELISA. Out of these patients, 25 underwent surgery and their paraffin-embedded tissue was analyzed for cathepsin L expression by immunohistochemistry. Survival of patients and clinicopathological parameters was correlated with cathepsin L expression in plasma and tissue using appropriate statistical analysis.

RESULTS: The mean (± SD) cathepsin L in plasma samples of pancreatic cancer patients was 5.98 ± 2.5 ng/mL that was significantly higher compared to the levels in healthy controls (3.83 ± 0.45) or chronic pancreatitis patients (3.97 ± 1.06). Using ROC curve, a cut-off level of 5.0 ng/mL was decided for survival analysis. Elevated plasma levels of cathepsin L were found to be associated with poor prognosis (P = 0.01) in multivariate analysis. The plasma levels of the protease decreased after surgery. Though no significant correlation was seen between plasma and tissue expression of this protease, a trend did emerge that high cathepsin L expression in tissue correlated with its high levels in plasma.

CONCLUSION: Cathepsin L levels in plasma of pancreatic cancer patients may be used as a potential prognostic marker for the disease.

Core tip: Cathepsin L is a lysosomal cysteine protease, which degrades extracellular matrix during cancer cell invasion. It has been shown to have prognostic value in pancreatic tumor tissue. But blood based markers can be more useful. Elevated levels of cathepsin L in plasma have been reported but no study has exhibited prognostic significance of cathepsin L levels in blood. This study for the first time reported that elevated levels of cathepsin L in plasma predict poor prognosis in pancreatic cancer and these levels decrease after surgery.

- Citation: Singh N, Das P, Gupta S, Sachdev V, Srivasatava S, Datta Gupta S, Pandey RM, Sahni P, Chauhan SS, Saraya A. Plasma cathepsin L: A prognostic marker for pancreatic cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17532-17540

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17532.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17532

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths with a 5-year survival rate of only 5%[1,2]. At present, surgical resection is the only choice of treatment for pancreatic cancer but post-resection recurrence is common in 80%-90% of patients that undergo surgery[3].

Pancreatic cancer is an aggressive disease and the major phenomena that contribute to this behavior are invasion and rapid metastasis. Invasion and metastasis of solid tumors requires the activity of tumor-associated proteolytic enzymes. Cysteine proteases (Cathepsin B, cathepsin L, plasmin, μPA) are actively involved in modifying extracellular matrix and thus help in invasion[4-7].

Cathepsin L is expressed in human and mouse pancreas and has been found in the lysosomes of acinar cells as well as in pancreatic juice[8]. In normal cells, the acidic pH of the lysosomes activate it. However upon malignant transformation, instead of being transported into the lysosomal compartment, cathepsins are often translocated to cell-surface and secreted into the surrounding medium[9]. Thereafter the local acidic microenvironment of the tumor facilitates the activity of extracellular cathepsin L[10] thus helping in invasion and metastasis[11,12]. Many cancers, of kidney, testicular, breast, ovary and colon express cathepsin L in higher amounts than in normal tissue[13]. Cathepsin L expression in tumor tissue has been studied in bladder cancer[14], human gliomas[15], nasopharyngeal cancer[16] and was found to predict poor prognosis. It has also been evaluated for its prognostic significance in pancreatic tumor tissue and was found to correlate with poor survival[17]. However, it is difficult to obtain pancreatic tissue because it is a deep-seated organ. So, it was of interest to explore blood-based markers for predicting prognosis.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate the levels of cathepsin L protein in blood of pancreatic cancer patients and to look for any clinical and/or prognostic significance of this protease in pancreatic cancer. Also, the expression of this protein was assessed semi-quantitatively in sections of pancreatic carcinomas in patients who underwent resection, to look for any correlation between the plasma levels and the protein expression pattern in the tissue.

The study was performed on 127 consecutive confirmed pancreatic cancer patients who came to Department of Gastroenterology and Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, All India Institute of Medical Sciences between 2007 and 2011. The diagnosis was confirmed on the basis of CE-CT scan (using pancreatic protocol) and/or histopathological evidences. Patients that were found to have Periampullary carcinoma, Neuroendocrine Tumor or Insulinoma were excluded. The study was approved by the institute’s Ethics Committee and informed consent was taken from all patients who were recruited. Blood samples of patients were drawn and collected in vacutainers. The plasma was separated by centrifuging at 2000 g for 10 min at room temperature, within two hours of blood collection. The separated plasma was divided into 200 μL aliquots and stored at -80 °C till further use.

The plasma samples of 26 healthy subjects and 25 chronic pancreatitis patients were also collected as controls. It was confirmed that at the time of blood collection none of the healthy controls had any disease nor they were on any medications. The diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis was made based on ultrasound investigations along with typical clinical history including recurrent pancreatic pain, steatorrhea and/or diabetes.

Of the 127 pancreatic cancer patients who were recruited, 25 underwent surgical resection of the tumor. Surgery was done in patients with localized resectable pancreatic cancer, one where the lesion is restricted to the pancreas and its draining lymph nodes without involvement of the superior mesenteric artery, a patent superior mesenteric/portal venous system and no distant metastasis. These specimens were processed at the Department of Pathology, AIIMS and the paraffin blocks were prepared. Remaining patients were unresectable and were offered other palliative or chemotherapeutic procedures. Three month post-operative blood samples were collected from patients who underwent surgical tumor resection and were processed and stored; their clinical data was recorded to look for any recurrence of the disease.

The concentration of cathepsin L in the plasma of patients with carcinoma of pancreas was determined using the ELISA kit (Calbiochem, Merck, United States) as per manufacturer’s instructions. Standards of concentrations - 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.1 ng/mL were used. Undiluted plasma samples were added in the designated wells of ELISA plate. A standard curve for cathepsin L was plotted and concentration of cathepsin L in plasma samples of patients was extrapolated from this curve.

The cathepsin L protein expression was determined by immunohistochemical technique on formalin fixed paraffin-embedded tissue specimens of 25 patients who underwent surgical tumor resection. Sections (5 μm thick) of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded specimens were taken on poly-L-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, United States) coated glass slides and then deparaffinized serially with xylene (2 washes), xylene: acetone (1:1), 100% ethanol, 90% ethanol, 70% ethanol (each for 10 min) and finally with deionized water. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating the slides at 100 °C for 30 min in 0.01 mol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidases were then blocked by incubation with 4% H2O2 (in methanol). To block non-specific staining, background sniper (Biocare Medical, United States) was applied to sections for 5 min. After washing with TBS, the slides were incubated with 1:100 dilution (in TBS) of the primary antibody- anti-Cathepsin L (AbD Serotec, United Kingdom) overnight at 4 °C followed by 3 washes in TBS. Sections were then incubated with secondary antibody (Biocare Medical) for 15 min at room temperature and washed with TBS thrice. The slides were subsequently incubated with peroxidases (MACH 4 Universal HRP-Polymer kit, Biocare Medical) for 15 min followed by washing thrice (5 min each). Finally, the slides were incubated with Diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution (32 μL DAB + 1 μL substrate) followed by washing with deionized water. After counterstaining with haematoxylin, the slides were dried and mounted with DPX.

Each slide was evaluated for cathepsin L immunostaining using a semi-quantitative scoring system for both staining intensity and the percentage of positive cells developed in-house for the convenience of uniform reporting. Sections were scored as positive if immunopositivity was noticed in either the cytoplasm or membrane of > 10% of epithelial and stromal cells. The tissue sections were scored based on the percentage of immunostained cells as follows: 0-10% = 0; 11%-20% = 1; 21%-40% = 2; 41%-60%= 3; 61%-80% = 4; and 81%-100% = 5. Sections were also scored semi-quantitatively on the basis of staining intensity as negative = 0; mild = 1; moderate = 2; intense = 3. The intensity of well standardized control slides were taken as grade 3 intensity. When the stain was just appreciable with light microscopy, it was graded as grade 1 intensity. Any stain intensity in-between was graded as grade 2 intensity. Sections of carcinoma breast with infiltrating ducts stained with cathepsin L were taken as positive control. Staining was evaluated in the neoplastic epithelium and in the intervening stroma independently. In each slide, a minimum of 20 fields were evaluated using a × 10 objective lens. Average of scoring in all fields examined was taken as the final score. The cathepsin L expression pattern in tumor was compared to that of non-neoplastic pancreatic tissue.

To compare variables within two groups, Student’s t test, Mann Whitney U test or chi square test were applied as appropriate. For comparing parameters before and after surgery, paired t test was used. Kaplan Meier method[18] was used to measure cumulative survival probability as a function of time and the cut-off was set by drawing ROC (Receiver Operating Curve). The difference in survival time between groups was compared using Log Rank test[19]. To find the significance of parameters as an independent prognostic marker, Cox regression multivariate analysis was applied.

A P value of < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. The software SPSS 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical analysis.

The mean age of the patients in the study group was 55 ± 10.2 years. Among the pancreatic cancer patients recruited in the study, 88 were males and 39 were females. On the basis of imaging parameters, tumor was found to be at resectable stage in 40 (31.4%) patients. But after further investigations, namely biopsy or FNAC, and during surgery, the number of patients who actually had resectable tumor was 25 (19.6%). Clinical investigations describing the patient disease status are given in Table 1.

| Clinical parameters | n (%) |

| Pain | 93 (73.2) |

| Jaundice | 83 (65.4) |

| Anorexia | 106 (83.5) |

| Wt. Loss | 107 (84.3) |

| Diabetes | 38 (30.0) |

| Chronic pancreatitis history | 17 (13.4) |

| Common bile Duct dilated | 84 (66.0) |

| Main Pancreatic Duct dilated | 98 (77.2) |

| Locally advanced disease | 87 (68.5) |

| Lymphatic invasion | 50 (39.4) |

| Vascular encasement | 59 (46.5) |

| Metastasis | 52 (41.0) |

| Resectability | 25 (19.6) |

| Chemotherapy | 59 (46.5) |

Amongst healthy controls taken in the study, 15 were males and 11 were females with a mean age of 33 ± 14 years. Out of the 25 chronic pancreatitis patients included in this study, 17 were males and 8 were females with a mean age of 34 ± 12 years.

Serum levels of CA19.9 were recorded for 96 (75.6%) patients and the mean level was 2772.8 ± 981 U/mL.

Of all the patients recruited in the study, 101 patients died due to the disease, 8 patients were found living until the last follow-up (3 years) done, 6 patients died due to reason other than pancreatic cancer while 12 patients were lost to follow-up. Overall survival time of the patients refers to the period between the day on which sample was taken and the day of death of the patients. The median overall survival time of all the patients taken together was 5 mo (range 1-36 mo). Patients who were lost to follow-up were considered alive and their survival time was recorded until the last follow-up.

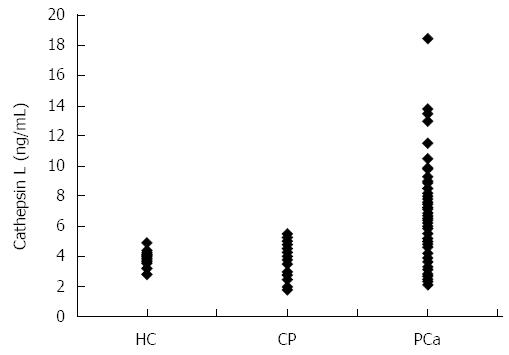

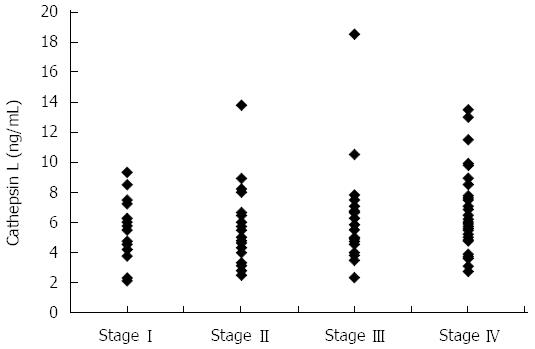

ELISA was employed to assess cathepsin L levels in plasma samples of the 127 patients with pancreatic cancer. The mean ± SD cathepsin L in plasma samples of pancreatic cancer patients was 5.98 ± 2.5 ng/mL. This was significantly higher compared to the levels in healthy controls (3.83 ± 0.45 ng/mL) (independent t test; P < 0.001) as well as to levels in chronic pancreatitis patients (3.97 ± 1.06 ng/mL) (independent t test; P < 0.001). A dot plot showing the cathepsin L levels of patients with pancreatic cancer, chronic pancreatitis and healthy individuals is given in Figure 1. However, no significant correlation was observed between any of the clinicopathological parameters (like age, sex, tumor size, vascular encasement, lymphatic invasion, metastasis and disease stage) and plasma cathepsin L levels. Figure 2 shows the cathepsin L levels in patients with different disease stages as a dot plot.

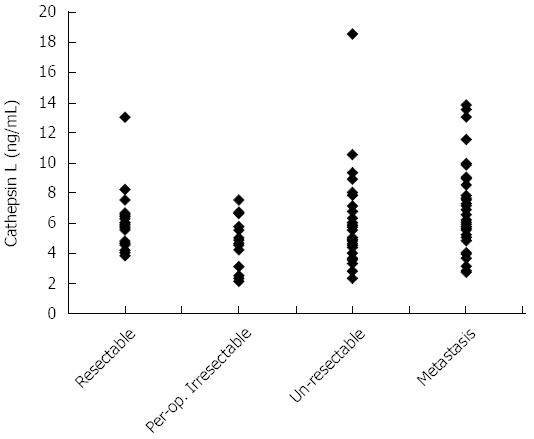

Though a comparison of the cathepsin L levels between patients with resectable (n = 25) and unresectable (n = 102) disease showed no significant difference (5.7 ± 1.8 ng/mL vs 6.0 ± 2.6 ng/mL respectively, P = 0.556), the cathepsin L levels of patients with resectable malignancy was significantly (P < 0.001) higher than those of benign pancreatic disease or healthy individuals (3.88 ± 0.81 ng/mL). Cathepsin L levels of patients with resectable disease has been plotted in Figure 3 along with the levels in patients of various categories of unresectable disease.

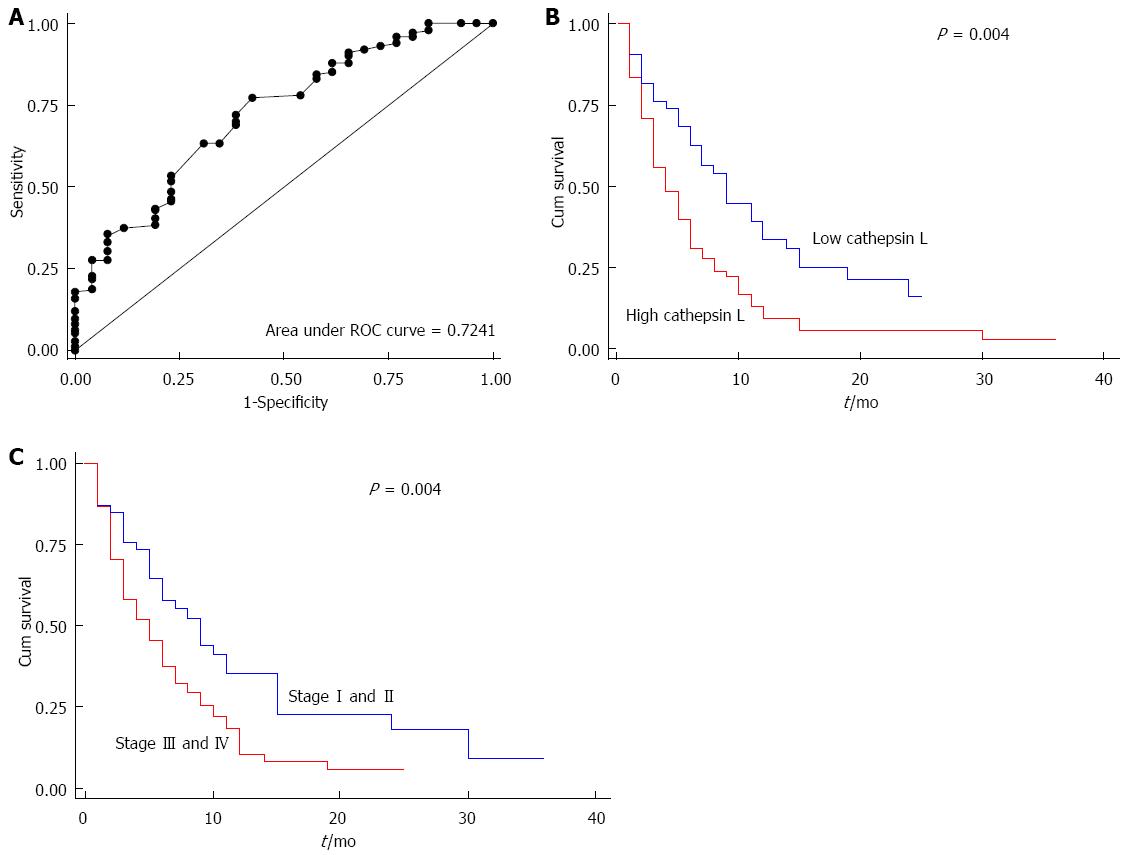

Receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was used to calculate the cut off for the survival analysis. The ROC curve was drawn for cathepsin L and the area under the curve was 0.724 (Figure 4A). The strength of the statistical association of cathepsin L levels in plasma with prognosis was assessed by Kaplan-Meier survival analysis.

Using ROC analysis, a cut-off level of cathepsin L was taken at 5.0 ng/mL where optimal sensitivity and specificity were 69.31% and 61.54% respectively. Kaplan-Meier univariate survival analysis showed significantly reduced median overall survival of 4 months in patients with increased level of plasma cathepsin L (> 5 ng/mL), compared with median overall survival of 9 mo in the patients with low concentrations (≤ 5 ng/mL) of plasma cathepsin L (log rank test; P = 0.004) (P = 0.01; HR = 1.7, 95%CI: -1.15-2.25) (Tables 2 and 3). Kaplan-Meier survival curve showing cumulative survival as a function of time for low and high levels of cathepsin L is given in Figure 4B.

| Parameters | No. of cases | Death n (%) | Median survival in months (95%CI) | P value1 |

| Age(yr): | ||||

| < 55 | 58 | 46 (80.0) | 5 (3.1-6.8) | 0.313 |

| ≥ 55 | 69 | 54 (78.2) | 7 (4.9-9.0) | |

| Sex: | ||||

| Male | 88 | 70 (80.4) | 6 (4.9-7.0) | 0.682 |

| Female | 39 | 30 (77.0) | 5 (2.1-7.9) | |

| Tumor mass (cm): | ||||

| ≥ 2 | 101 | 82 (81.0) | 6 (4.5-7.4) | 0.202 |

| < 2 | 26 | 18 (72.0) | 5 (2.1-7.8) | |

| Vascular encasement: | ||||

| No | 65 | 46 (71.8) | 6 (3.7-8.3) | 0.003 |

| Yes | 62 | 53 (86.8) | 4 (2.4-5.5) | |

| Locally advanced: | ||||

| No | 39 | 28 (73.6) | 8 (5.1-10.8) | 0.008 |

| Yes | 88 | 72 (81.8) | 5 (3.3-6.6) | |

| Lymphatic invasion: | ||||

| No | 73 | 55 (76.3) | 6 (4.5-7.5) | 0.231 |

| Yes | 54 | 45 (85.0) | 6 (4.0-8.0) | |

| Metastasis: | ||||

| No | 74 | 55 (74.3) | 9 (7.0-11.0) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 53 | 45 (86.5) | 3 (2.0-4.0) | |

| Surgery: | ||||

| No | 102 | 81 (79.4) | 6 (4.7-7.2) | 0.349 |

| Yes | 25 | 20 (80.0) | 6 (4.4-7.5) | |

| Chemotherapy: | ||||

| Yes | 73 | 57 (79.0) | 6 (4.2-7.7) | 0.602 |

| No | 54 | 43 (79.6) | 4 (1.1-6.8) | |

| Stage: | ||||

| I + II | 48 | 35 (72.9) | 9 (5.5-12.4) | 0.004 |

| III + IV | 79 | 66 (83.5) | 5 (3.3-6.6) | |

| Cathepsin L: | ||||

| Low ( ≤ 5 ng/mL) | 54 | 38 (70.3) | 9 (6.7-11.2) | 0.004 |

| High (> 5 ng/mL) | 73 | 63 (86.3) | 4 (2.5-5.4) | |

| Parameters | No. of patients | Deaths n (%) | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

| Unadjusted | P value | Adjusted | P value | |||

| HR | HR | |||||

| (95%CI) | (95%CI) | |||||

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| < 55 | 58 | 46 (80.0) | 1 | - | - | |

| ≥ 55 | 69 | 54 (78.2) | 0.8 | 0.337 | ||

| (0.55-1.22) | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 88 | 70 (80.4) | 1 | - | - | |

| Female | 39 | 30 (77.0) | 0.9 | 0.720 | ||

| (0.60-1.42) | ||||||

| Tumor mass (cm) | ||||||

| < 2 | 26 | 18 (72.0) | 1 | - | - | |

| ≥ 2 | 101 | 82 (81.0) | 1.3 | 0.234 | ||

| (0.8-2.2) | ||||||

| Vascular encasement | - | |||||

| No | 65 | 46 (71.8) | 1 | - | ||

| Yes | 62 | 53 (86.8) | 1.7 | 0.007 | ||

| (1.16-2.61) | ||||||

| Locally advanced | ||||||

| No | 39 | 28 (73.6) | 1 | - | - | |

| Yes | 88 | 72 (81.8) | 1.7 | 0.014 | ||

| (1.12-2.76) | ||||||

| Lymphatic invasion | ||||||

| No | 73 | 55 (76.3) | 1 | - | - | |

| Yes | 54 | 45 (85.0) | 1.3 | 0.232 | ||

| (0.85-1.89) | ||||||

| Metastasis | ||||||

| No | 74 | 55 (74.3) | 1 | - | - | |

| Yes | 53 | 45 (86.5) | 2.1 | 0.001 | ||

| (1.4-3.1) | ||||||

| Surgery | ||||||

| No | 102 | 81 (79.4) | 1 | - | - | |

| Yes | 25 | 20 (80.0) | 0.79 | 0.380 | ||

| (0.48-1.3) | ||||||

| Stage | ||||||

| I + II | 48 | 35 (72.9) | 1 | 1 | ||

| III + IV | 79 | 66 (83.5) | 1.7 | 0.008 | 1.7 | 0.008 |

| (1.1, 2.7) | (1.1-2.6) | |||||

| Cathepsin L | ||||||

| Low ( ≤ 5 ng/mL) | 54 | 38 (70.3) | 1 | 1 | 0.010 | |

| High (> 5 ng/mL) | 73 | 63 (87.5) | 1.7 | 0.010 | 1.7 | |

| (1.15-2.25) | (1.1-2.5) | |||||

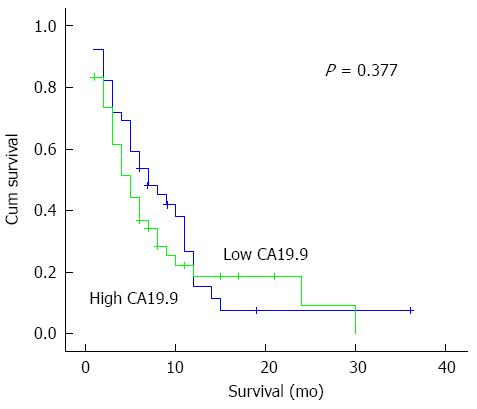

Among the other clinicopathological parameters, shorter survival correlated with patients having vascular encasement (P = 0.003), metastasis (P = 0.001), locally advanced disease (P = 0.008) and stage of the disease (P = 0.004) as expected (Tables 2 and 3). However, CA19-9 levels did not correlate with survival (Figure 5).

Cox regression multivariate analysis indicated that plasma level of cathepsin L (P = 0.01; HR = 1.7, 95%CI:-1.1-2.5) and stage of the disease (P = 0.008; HR = 1.7, 95%CI: -1.1-2.7) were independent prognostic factors for patients with pancreatic cancer (Table 3). Kaplan-Meier survival curve for stage of the disease is shown in Figure 4C.

Levels of cathepsin L were also examined in plasma of 14 patients collected 3 mo after resection of tumor. The other 9 patients who underwent surgery either died before 3 mo or were not available for sample collection (their survival data was recorded through phone). The mean levels of cathepsin L before surgery were 6.6 ± 1.24 ng/mL but decreased to 3.9 ± 1.1 ng/mL in samples taken 3 mo after surgery. There was a significant decrease found in cathepsin L levels (P < 0.001) after surgery.

No correlation was found between the levels of cathepsin L and CA19-9 marker (r = 0.148; P = 0.131) (n = 96). However, in 14 patients who were followed up after resection, 10 patients showed recurrence of disease. Patients with distant recurrence (n = 3) after surgery had higher levels of both cathepsin L (3.9 ± 2.2 ng/mL) and CA19-9 (3546 ± 1210 U/mL) compared to Cathepsin L (3.1 ± 1.7 ng/mL) and CA19-9 (457 ± 213 U/mL) in patients with local recurrence (n = 7). The four patients who did not have recurrence after 3 mo had even lower Cathepsin L (2.5 ± 1.2 ng/mL) and CA19-9 (342 ± 212 U/mL).

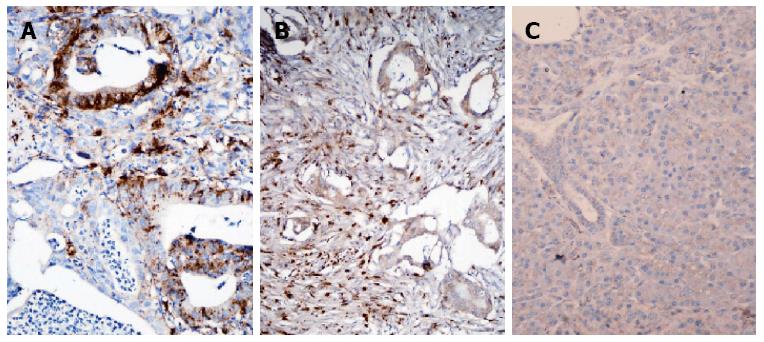

As described above, 25 of these patients underwent surgical tumor resection and hence, their tumor tissue was available. IHC for cathepsin L was performed on these tissue specimens and graded as described previously. In pancreatic tumor specimens, the expression of this cysteine protease was found mainly to be cytoplasmic and was relatively stronger in tumor stroma, than that in epithelial cells (Figure 6A and B). Cathepsin L expression was low (none or weak immunoreactivity) in 12% (3/25) of cases and high (moderate to strong) in 88% (22/25) of cases. Non-neoplastic pancreatic tissue was used as a negative control and showed minimal staining (Figure 6C).

To see the concordance between tissue and blood levels of cathepsin L, its expression in tumor tissue of these 25 patients was compared with the levels in their blood samples. The levels of cathepsin L in tissue as well as in blood were individually divided into low expression (0-4 scores) and high expression (5-8 scores) categories and then analyzed for any correlation. As shown in Table 4, 18 patients had high expression both in the tissue as well as plasma, 4 patients had high tissue expression of cathepsin L but not in blood; while 3 patients had high plasma levels of cathepsin L but low expression in tissues. Thus correlation of cathepsin L levels in blood and tissue was rendered insignificant (P = 0.706) (Table 4).

| Cathepsin L in blood | P value | ||

| Low ( ≤5 ng/mL) | High (> 5 ng/mL) | ||

| Cathepsin L in tissue low (0-4 scores) | 0 | 3 | 0.706 |

| Cathepsin L in tissue high (5-8 scores) | 4 | 18 | |

The prognostic significance of cathepsin L expression in tumor tissue has been studied in many cancers including bladder cancer[14], human gliomas[15], nasopharyngeal cancer[16] and breast cancer[6,20,21]. In pancreatic cancer, two studies have evaluated the prognostic significance of cathepsin L expression in tumor tissue. Niedergethmann et al[17] showed expression of cathepsin L in 87.6% of cases (n = 29) which exhibited significant correlation with survival after surgery. In a later study by the same group[22], expression of both cathepsin L and cathepsin B was assessed in 70 tumor tissues of pancreatic carcinoma. Expression of both cathepsins was found to be significant independent prognostic markers by them. Similarly in our previous study, it was found that high epithelial expression of cathepsin L in pancreatic tumor tissue was associated with poor survival of patients[23].

Many studies have shown the presence of cathepsin L in blood of cancer patients. Nishida et al[24] demonstrated that both mRNA and protein levels of cathepsin L in serum were increased in patients with ovarian cancers. Cathepsin L was also found to be elevated in the sera of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma as compared to that of normal subjects as well as liver cirrhosis patients[25]. Similarly, in this study, the plasma levels of cathepsin L were significantly elevated in patients with pancreatic cancer as compared to that of healthy subjects. Hence, it is possible that Cathepsin L levels may help in distinguishing patients with malignant disease from healthy or benign cases. This is also in agreement with previous studies[26,27] that evaluated serum cathepsin L levels in pancreatic cancer. Both the studies showed significantly elevated serum cathepsin L levels in patients with pancreatic carcinoma as compared to normal subjects and pancreatitis patients.

To the best of our knowledge, the prognostic significance of cathepsin L levels in blood of pancreatic cancer patients were not demonstrated previously. Very few studies are available regarding the prognostic relevance of serum/plasma levels of cathepsin L in patients of other cancer types. High levels of plasma cathepsin L were shown to be associated with poor survival in colorectal cancer[28]. Chen et al[29] also evaluated cathepsin L levels in serum of lung cancer patients but did not find any association with survival or other clinicopathological parameters. However, our results demonstrated significant correlation between cathepsin L levels in plasma of patients and poor survival in univariate analysis (Table 2). On multivariate analysis, plasma cathepsin L level along with stage of the disease was found to be an independent prognostic marker for pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Table 3).

Post-surgery plasma samples of 14 patients who underwent resection were analyzed for cathepsin L levels. There was a significant decrease in cathepsin L levels after surgery. This decrease can be attributed to resection of the tumor and hence reduced tumor load which may be responsible for the release of cathepsin L in the tumor microenvironment and subsequently in blood.

CA 19-9 also has a great relevance as a prognostic factor in the post-operative period. In a study on pancreatic cancer, a high CA 19-9 serum level (greater than 200 U/mL) after surgery correlated with early mortality, higher tumor stage and positive lymph nodes[30]. In our study, the mean levels of cathepsin L and CA19-9 of patients with distant recurrence was observed to be more as compared to patients with local recurrence. However, since the sample size is very small, no statistical test could be applied, though these observations show a trend that cathepsin L levels might also be used to predict recurrence after surgery.

Cathepsin L expression in pancreatic tumor tissue was assessed and the expression was significantly elevated in tumor tissue as compared to non-neoplastic tissue. Of the 25 patients who underwent surgery, plasma cathepsin L levels (ng/mL) were found to correlate neither with cathepsin L expression (scores) in tumor epithelium nor with stromal cathepsin L expression (scores). One possible reason could be that expression of this protein was assessed semi-quantitatively in tissue (in scores) and quantitatively (in ng/mL) in blood samples which may result in no correlation between the two.

For the above-mentioned reason, the levels of cathepsin L in tissue as well as in blood were individually divided into low and high categories and then analyzed for any correlation. Even though the number of samples was too low to show any significant correlation between the blood and tissue levels of cathepsin L, a trend did emerge that high cathepsin L expression in tissue correlated with its high levels in blood.

In conclusion, this study showed that plasma cathepsin L may be used as an independent predictor of prognosis in pancreatic cancer. This protease may be one of the factors responsible for tumor invasion, as its level was found to be significantly higher in the pancreatic tumor tissues in comparison to non-neoplastic adjacent tissues.

Pancreatic cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related deaths. It has a propensity for wide stromal invasion. Cathepsin L is a cysteine protease that degrades the peri-tumoral tissue and helps in tumor dissemination. Previous studies have shown that pancreatic tumor tissue have higher expression of cathepsin L which correlates with poorer survival. However, no studies report prognostic significance of plasma cathepsin L levels in pancreatic cancer.

This study was undertaken to assess the prognostic significance of plasma cathepsin L levels in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Earlier studies showed that expression level of cathepsin L in the pancreatic cancer tissue could predict prognosis. However, only about 10% of the patients have resectable disease. So, in this study the authors checked if the tissue expression of cathepsin L correlated with its levels in the plasma and if this plasma cathepsin L could be used to predict prognosis. The authors observed that plasma cathepsin L levels in the pancreatic cancer patients were higher than the levels in healthy individuals or patients with benign pancreatic disease and also that higher levels predicted poor prognosis.

This study showed that plasma cathepsin L may be used as a potential predictor of prognosis in pancreatic cancer.

Cathepsin L: a cysteine protease that degrades the extracellular matrix and thus helps in tumor dissemination / invasion.

The article would benefit from the following remarks: The authors have investigated 127 consecutive patients with pancreatic cancer, 26 healthy controls and 25 patients with chronic pancreatitis.

P- Reviewer: Braat H, Chen RF S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | DiMagno EP, Reber HA, Tempero MA. AGA technical review on the epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1464-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 260] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wray CJ, Ahmad SA, Matthews JB, Lowy AM. Surgery for pancreatic cancer: recent controversies and current practice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1626-1641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Sitzmann JV, Hruban RH, Goodman SN, Dooley WC, Coleman J, Pitt HA. Pancreaticoduodenectomy for cancer of the head of the pancreas. 201 patients. Ann Surg. 1995;221:721-731; discussion 731-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 735] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Denhardt DT, Greenberg AH, Egan SE, Hamilton RT, Wright JA. Cysteine proteinase cathepsin L expression correlates closely with the metastatic potential of H-ras-transformed murine fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1987;2:55-59. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Kobayashi H, Schmitt M, Goretzki L, Chucholowski N, Calvete J, Kramer M, Günzler WA, Jänicke F, Graeff H. Cathepsin B efficiently activates the soluble and the tumor cell receptor-bound form of the proenzyme urokinase-type plasminogen activator (Pro-uPA). J Biol Chem. 1991;266:5147-5152. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Lah TT, Kokalj-Kunovar M, Strukelj B, Pungercar J, Barlic-Maganja D, Drobnic-Kosorok M, Kastelic L, Babnik J, Golouh R, Turk V. Stefins and lysosomal cathepsins B, L and D in human breast carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1992;50:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sloane BF. Cathepsin B and cystatins: evidence for a role in cancer progression. Semin Cancer Biol. 1990;1:137-152. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wartmann T, Mayerle J, Kähne T, Sahin-Tóth M, Ruthenbürger M, Matthias R, Kruse A, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Weiss FU. Cathepsin L inactivates human trypsinogen, whereas cathepsin L-deletion reduces the severity of pancreatitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:726-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mohamed MM, Sloane BF. Cysteine cathepsins: multifunctional enzymes in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:764-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 981] [Cited by in RCA: 953] [Article Influence: 50.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lankelma JM, Voorend DM, Barwari T, Koetsveld J, Van der Spek AH, De Porto AP, Van Rooijen G, Van Noorden CJ. Cathepsin L, target in cancer treatment? Life Sci. 2010;86:225-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Collette J, Bocock JP, Ahn K, Chapman RL, Godbold G, Yeyeodu S, Erickson AH. Biosynthesis and alternate targeting of the lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin L. Int Rev Cytol. 2004;241:1-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nomura T, Katunuma N. Involvement of cathepsins in the invasion, metastasis and proliferation of cancer cells. J Med Invest. 2005;52:1-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Liotta LA. Tumor invasion and metastases--role of the extracellular matrix: Rhoads Memorial Award lecture. Cancer Res. 1986;46:1-7. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Yan JA, Xiao H, Ji HX, Shen WH, Zhou ZS, Song B, Chen ZW, Li WB. Cathepsin L is associated with proliferation and clinical outcome of urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. J Int Med Res. 2010;38:1913-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sivaparvathi M, Yamamoto M, Nicolson GL, Gokaslan ZL, Fuller GN, Liotta LA, Sawaya R, Rao JS. Expression and immunohistochemical localization of cathepsin L during the progression of human gliomas. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1996;14:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu X, Yuan G, Liu W, Zhang Y, Chen W. Expression of cathepsin L in nasopharyngeal carcinoma and its clinical significance. Exp Oncol. 2009;31:102-105. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Niedergethmann M, Hildenbrand R, Wolf G, Verbeke CS, Richter A, Post S. Angiogenesis and cathepsin expression are prognostic factors in pancreatic adenocarcinoma after curative resection. Int J Pancreatol. 2000;28:31-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparameteric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457-458. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32610] [Cited by in RCA: 31230] [Article Influence: 466.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Mantel N. Evaluation of survival data and two new rank order statistics arising in its consideration. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:163-170. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Foekens JA, Kos J, Peters HA, Krasovec M, Look MP, Cimerman N, Meijer-van Gelder ME, Henzen-Logmans SC, van Putten WL, Klijn JG. Prognostic significance of cathepsins B and L in primary human breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:1013-1021. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Thomssen C, Schmitt M, Goretzki L, Oppelt P, Pache L, Dettmar P, Jänicke F, Graeff H. Prognostic value of the cysteine proteases cathepsins B and cathepsin L in human breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1:741-746. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Niedergethmann M, Wostbrock B, Sturm JW, Willeke F, Post S, Hildenbrand R. Prognostic impact of cysteine proteases cathepsin B and cathepsin L in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2004;29:204-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Singh N, Das P, Datta Gupta S, Sahni P, Pandey RM, Gupta S, Chauhan SS, Saraya A. Prognostic significance of extracellular matrix degrading enzymes-cathepsin L and matrix metalloproteases-2 [MMP-2] in human pancreatic cancer. Cancer Invest. 2013;31:461-471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Nishida Y, Kohno K, Kawamata T, Morimitsu K, Kuwano M, Miyakawa I. Increased cathepsin L levels in serum in some patients with ovarian cancer: comparison with CA125 and CA72-4. Gynecol Oncol. 1995;56:357-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Leto G, Tumminello FM, Pizzolanti G, Montalto G, Soresi M, Gebbia N. Lysosomal cathepsins B and L and Stefin A blood levels in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and/or liver cirrhosis: potential clinical implications. Oncology. 1997;54:79-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tumminello FM, Leto G, Pizzolanti G, Candiloro V, Crescimanno M, Crosta L, Flandina C, Montalto G, Soresi M, Carroccio A. Cathepsin D, B and L circulating levels as prognostic markers of malignant progression. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2315-2319. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Leto G, Tumminello FM, Pizzolanti G, Montalto G, Soresi M, Carroccio A, Ippolito S, Gebbia N. Lysosomal aspartic and cysteine proteinases serum levels in patients with pancreatic cancer or pancreatitis. Pancreas. 1997;14:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Herszényi L, Farinati F, Cardin R, István G, Molnár LD, Hritz I, De Paoli M, Plebani M, Tulassay Z. Tumor marker utility and prognostic relevance of cathepsin B, cathepsin L, urokinase-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1, CEA and CA 19-9 in colorectal cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chen Q, Fei J, Wu L, Jiang Z, Wu Y, Zheng Y, Lu G. Detection of cathepsin B, cathepsin L, cystatin C, urokinase plasminogen activator and urokinase plasminogen activator receptor in the sera of lung cancer patients. Oncol Lett. 2011;2:693-699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Ferrone CR, Finkelstein DM, Thayer SP, Muzikansky A, Fernandez-delCastillo C, Warshaw AL. Perioperative CA19-9 levels can predict stage and survival in patients with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2897-2902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 355] [Cited by in RCA: 414] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |