Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17434

Revised: August 16, 2014

Accepted: September 18, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 285 Days and 7.5 Hours

AIM: To examine the efficiency of oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique in decreasing the rate of postoperative gastrooesophageal reflux disease in a dog model.

METHODS: We operated on 10 dogs in this study. First, we resected a 5-cm portion of the distal oesophagus and then restored the continuity of the oesophageal and gastric walls by end-to-end anastomosis. A group of five dogs was subjected to the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique, whereas another group (control) of five dogs was subjected to the stapling technique after oesophagectomy. The symptom of gastrooesophageal reflux was recorded by 24-h pH oesophageal monitoring. Endoscopy and barium swallow examination were performed on all dogs. Anastomotic leakage was observed by X-ray imaging, whereas benign anastomotic stricture and mucosal damage were observed by endoscopy.

RESULTS: None of the 10 dogs experienced anastomotic leakage after oesophagectomy. Four dogs in the new technology group resumed regular feeding, whereas only two of the dogs in the control group tolerated solid food intake. pH monitoring demonstrated that 25% of the dogs in the experimental group exhibited reflux and that none had mucosal damage consistent with reflux. Conversely, both reflux and mucosal damage were observed in all dogs in the control group.

CONCLUSION: The oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique can improve the postoperative quality of life through the long-term elimination of reflux oesophagitis and decreased stricture formation after primary oesophageal anastomosis.

Core tip: This study describes the use of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique to decrease the rate of postoperative gastrooesophageal reflux disease in a dog model after oesophagectomy. None of the 10 dogs experienced anastomotic leakage after oesophagectomy. Four dogs in the new technology group resumed regular feeding, whereas only two of the dogs in the control group tolerated solid food intake. pH monitoring demonstrated that 25% of the dogs in the experimental group exhibited reflux and that none had mucosal damage consistent with reflux. This technique may provide a good alternative method for preventing gastrooesophageal reflux after anastomosis following oesophagogastrectomy for oesophageal cancer.

- Citation: Dai JG, Liu QX, Den XF, Min JX. Oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing prevent gastrooesophageal reflux disease in dogs after oesophageal anastomosis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17434-17438

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17434.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17434

The use of oesophagectomy to treat oesophageal cancer is associated with high morbidity and perioperative complications[1,2]. Even after undergoing oesophagectomy, cancer patients remain uncured and have a low quality of life[3]. The status of patients after oesophagectomy correlates with the severity of physical symptoms, which is limited by the refinements in surgical technique[4]. Approximately 60% to 80% of patients suffer from reflux of duodenal and gastric contents after subtotal oesophagectomy and reconstruction with a gastric conduit[5].

To avoid these complications, the factors leading to reflux and the measures taken to limit or prevent it have been explored for decades. Reflux after subtotal oesophagectomy is caused by resection or disruption of the normal anti-reflux mechanisms (angle of His and diaphragmatic hiatus). Furthermore, the negative intra-thoracic pressure and the positive intra-abdominal pressure conspire to promote reflux across the anastomosis. This phenomenon could only be considered if the reflux complications could be overcome by a method that will enhance the lower oesophageal pressure and form anti-reflux flaps in the distal oesophagus.

Many surgical manoeuvres have been previously described to prevent reflux after oesophagectomy[6]. Intercostal muscle grafts with segmental vessels have been fashioned to act as anti-reflux valves[7]. However, this method is seldom used at present because of its complex construction and better suitability to low intra-thoracic anastomoses. Many studies have attempted to create valve-like anastomoses by tunnelling the oesophagus through the muscular layer of the stomach[8,9].

However, the use of these techniques is limited for two reasons. First, they are commonly used for limited resection because a substantial length of the oesophagus is required. In addition, these methods are not easily applicable in standard oncological resections because of the limited availability of the oesophagus[10].

An anastomosis procedure in which a “globe” is fashioned by invagination of the gastric wall behind the oesophagus has been proven to control reflux. The mechanism of this procedure is similar to that of a posterior fundoplication, in which the gastric fundus is wrapped around the distal oesophagus to act as a valve[11-13].

The use of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique in the oesophagectomy setting has yet to be described. In addition, the effect of this new technique on postoperative gastrooesophageal reflux disease (GERD) after primary resection and anastomoses of the distal oesophagus remains unknown. In the current study, we examined the effect of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique on postoperative GERD after primary oesophageal anastomosis in a dog model. Our results suggest that the new technique can control reflux after end-to-end anastomosis following oesophagectomy.

We used 10 domestic dogs weighing 25.2 ± 2.5 kg for these experiments. The dogs had free access to standard laboratory pellets and water until 12 h before surgery. This study was carried out in strict accordance with the recommendations in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institutes of Health. The animal use protocol has been reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the Third Military Medical University.

A right thoraco-abdominal incision was performed in all experimental animals under general anaesthesia. The thoracic oesophagus was mobilised, and a 5 cm-long segment of the distal oesophagus was transected. In these animals, this segment represents approximately one-third of the total length of the oesophagus. The animals were then assigned randomly to groups A and B. In group B, a primary anastomosis was created between the end of the residual oesophageal and gastric walls using a common stapling technique.

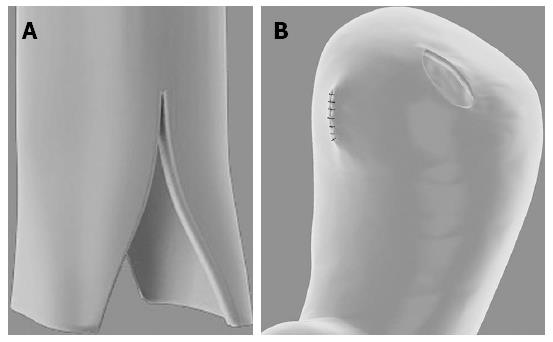

In group A, the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique was performed. We made a longitudinal cut on the distal oesophagus with a length of approximately 2-3 cm, forming two oesophageal flaps. A stoma was simultaneously made in the anterior wall of the stomach, which we named the “sleeve joint” (Figure 1). The site of the “sleeve joint” should be kept approximately 4 cm away from the top of the stomach wall, and the length of the “sleeve joint” should be 2 to 3 mm longer than the oesophageal diameter. Then, a 1 cm-long fold around the oesophageal flaps and remnant oesophagus was hand sutured using a neuromuscular layer of interrupted absorbable monofilament suture in the AA1 site (Figure 2). In the last step, seromuscular layer suturing was executed between the oesophageal and gastric walls in the BB1 and CC1 sites. The BB1 site was located just above the end of the oesophageal flaps, and the distance between BB1 and CC1 should be 2 cm (Figure 3).

Feeding gastrostomy concluded the surgical intervention in all experimental animals. Feeding was resumed via the gastrostomy tube for the first postoperative week, and a swallow study with gastrografin (Schering, Germany) was performed at the end of the week to rule out anastomotic leakage. The experimental animals were then granted free access to either blended or solid food, depending on the animals’ preference. Six weeks later, fluoroscopy using food impregnated with contrast material (barium sulphate) was performed to evaluate oesophageal motility patterns, and endoscopy was conducted to evaluate the level of mucosal damage[14]. pH monitoring was performed to demonstrate gastrooesophageal reflux[15]. The diameters of oesophageal lumen 1.5 cm below and above the anastomosis were evaluated by radiographic studies under standardised conditions for anastomotic circumference assessment. In addition, anastomotic leakage in dogs can also be easily observed by X-ray imaging.

The mean and standard error and deviation were calculated. Differences between groups were evaluated by the Student’s t-test, followed by Tukey’s test. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05.

All animals survived the surgery in good condition. None of the two groups exhibited clinical signs of anastomotic leakage. No difference in food tolerance was recorded in the first week when feeding was exclusively performed through gastrostomy. At the end of the first postoperative week, a contrast-swallow meal was accomplished, and radiographic signs of anastomotic leaks were not evident in either group.

After the last examination, the experimental animals were allowed to resume free oral intake. Four dogs (80%) in group A resumed their regular feeding habits, whereas two dogs (40%) in the control group tolerated the ingestion of solid food. Anastomotic stricture was reported in two dogs in group A and four dogs in group B (P < 0.05, Table 1).

| Group A | Group B | P value | |

| Weight (kg, mean ± SD) | 24.9 ± 2.7 | 25.5 ± 2.2 | - |

| Sex | - | ||

| Female | 3 | 3 | |

| Male | 2 | 2 | |

| Anastomotic leakage | 0 | 0 | - |

| Anastomotic strictures | 2 | 4 | - |

| Reflux | 1 | 5 | 0.024 |

| Mucosal damage | 0 | 4 | 0.024 |

Endoscope studies performed 6 wk after the operation revealed no mucosal damage in group A. Conversely, mucosal damage was observed in four of the control animals (Table 1). The results of pH monitoring showed that one dog in group A and all dogs in the control group exhibited reflux.

Reflux after oesophagectomy is a common problem that may adversely affect the quality of life of patients[16]. GERD complications, such as oesophagitis, which occurs in 27%-35% of patients, and columnar metaplasia, which includes intestinal (Barrett’s) metaplasia, have been observed in the remnant oesophagus after oesophagectomy[17,18].

Most of these complications cannot be fully treated successfully, which decreases the life quality of patients. Therefore, gastrooesophageal reflux should be seriously monitored as one of the postoperative complications after oesophagogastrectomy. Simple measures such as excluding as much of the stomach as possible from the abdominal compartment and enhancing gastric emptying by pyloric drainage procedures may help to control reflux. However, most anti-reflux reconstructions are complex or have been used only in a limited resection setting[7,19,20].

In the 1970s, Butterfield reported the use of fundoplication after palliative resection of the lower oesophagus, and Boyd et al[11] and Butterfield[13] described 55 patients, of whom 30 had a 5 cm fundoplication fashioned after oesophagogastric anastomosis during resection for oesophageal and proximal gastric cancers.

Fundoplication or wrapping the gastric fundus around the distal oesophagus to act as a valve is a successful method for treating de novo gastrooesophageal reflux. However, the extent of resection, particularly of the stomach, is limited by the current standards and the availability of the fundus to form the wrap. Thus, a modified fundoplication could be created. In this study, we reported the efficacy of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique in preventing postoperative gastrooesophageal reflux after oesophagogastrectomy. In the present study, anastomoses in patients of groups A and B were performed by hand suture and common stapling, respectively. In group A, no mucosal damage was observed by endoscopy, and only one case of reflux was reported by 24-h pH oesophageal monitoring. In the control group, four dogs had mucosal damage and all dogs exhibited gastrooesophageal reflux.

We propose that wrapping suturing with the oesophageal flap technology is a good alternative for preventing gastrooesophageal reflux after oesophagogastrectomy under the experimental conditions. In this study, this procedure was proven capable of preventing postoperative reflux after primary oesophageal anastomosis. However, the effects of reflux reduction strategies on the quality of life and pathological sequelae of patients must be evaluated in future studies.

Gastric acid reflux is a common complaint after primary oesophageal anastomosis in oesophageal cancer patients. Traditional hand-sewn and stapled techniques help to prevent gastric acid reflux. Recent studies have proven that fundoplication is effective in curing gastrooesophageal reflux disease (GERD). This study aims to examine the efficiency of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique, which is physiologically similar to a partial fundoplication, in decreasing the rate of postoperative GERD in a dog model.

Many surgical manoeuvres have been previously described to prevent reflux after oesophagectomy. Intercostal muscle grafts with segmental vessels have been fashioned to act as anti-reflux valves. However, this method is seldom used at present because of its complex construction and better suitability to low intra-thoracic anastomoses.

An anastomosis procedure in which a ‘globe’ is fashioned by invagination of the gastric wall behind the oesophagus has been proven to control reflux. The mechanism of this procedure is similar to that of a posterior fundoplication, in which the gastric fundus is wrapped around the distal oesophagus to act as a valve. The use of the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique in the oesophagectomy setting has yet to be described. In addition, the effect of this new technique on postoperative GERD after primary resection and anastomoses of the distal oesophagus remains unknown.

The study results suggest that the oesophageal flap valvuloplasty and wrapping suturing technique is a feasible procedure following oesophagectomy for oesophageal cancer.

This is a well-written and scientific description of oesophageal anastomotic techniques in a dog model over a relatively short time frame. The methodology and results are clear and helpful. This paper describes an interesting method of anastomosis after oesophagectomy for squamous cell carcinoma of the thoracic oesophagus. The authors are to be congratulated on their excellent results.

P- Reviewer: Chaturvedi P, Vollmers HP S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Zhang DN

| 1. | Müller JM, Erasmi H, Stelzner M, Zieren U, Pichlmaier H. Surgical therapy of oesophageal carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1990;77:845-857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 662] [Cited by in RCA: 624] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Atkins BZ, Shah AS, Hutcheson KA, Mangum JH, Pappas TN, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA. Reducing hospital morbidity and mortality following esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1170-1176; discussion 1170-1176. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Tolone S, Docimo G, Del Genio G, Brusciano L, Verde I, Gili S, Vitiello C, D’Alessandro A, Casalino G, Lucido F. Long term quality of life after laparoscopic antireflux surgery for the elderly. BMC Surg. 2013;13 Suppl 2:S10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Dai JG, Zhang ZY, Min JX, Huang XB, Wang JS. Wrapping of the omental pedicle flap around esophagogastric anastomosis after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surgery. 2011;149:404-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dresner SM, Griffin SM, Wayman J, Bennett MK, Hayes N, Raimes SA. Human model of duodenogastro-oesophageal reflux in the development of Barrett’s metaplasia. Br J Surg. 2003;90:1120-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yamada E, Shirakawa Y, Yamatsuji T, Sakuma L, Takaoka M, Yamada T, Noma K, Sakurama K, Fujiwara Y, Tanabe S. Jejunal interposition reconstruction with a stomach preserving esophagectomy improves postoperative weight loss and reflux symptoms for esophageal cancer patients. J Surg Res. 2012;178:700-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Demos NJ, Kulkarni VA, Port A, Micale J. Control of postresection gastroesophageal reflux: the intercostal pedicle esophagogastropexy experience of 26 years. Am Surg. 1993;59:137-148. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Wooler G. Reconstruction of the cardia and fundus of the stomach. Thorax. 1956;11:275-280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Watkins DH, Prevedel A, Harper FR. A method of preventing peptic esophagitis following esophagogastrostomy: experimental and clinical study. J Thorac Surg. 1954;28:367-379, discussion 379-382. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Lortat-Jacob JL, Maillard JN, Fekete F. A procedure to prevent reflux after esophagogastric resection: experience with 17 patients. Surgery. 1961;50:600-611. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Boyd AD, Cukingnan R, Engelman RM, Localio SA, Slattery L, Tice DA, Bardin JA, Spencer FC. Esophagogastrostomy. Analysis of 55 cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1975;70:817-825. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Okada N, Kuriyama T, Umemoto H, Komatsu T, Tagami Y. Esophageal surgery: a procedure for posterior invagination esophagogastrostomy in one-stage without positional change. Ann Surg. 1974;179:27-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Butterfield WC. Anti-reflux palliative resections for inoperable carcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1971;62:460-464. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Nishimura K, Fujita H, Tanaka T, Tanaka Y, Matono S, Murata K, Umeno H, Shirouzu K. Endoscopic classification for reflux pharyngolaryngitis. Dis Esophagus. 2010;23:20-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kleiman DA, Beninato T, Bosworth BP, Brunaud L, Ciecierega T, Crawford CV, Turner BG, Fahey TJ, Zarnegar R. Early referral for esophageal pH monitoring is more cost-effective than prolonged empiric trials of proton-pump inhibitors for suspected gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2014;18:26-33; discussion 33-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rickenbacher N, Kötter T, Kochen MM, Scherer M, Blozik E. Fundoplication versus medical management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:143-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lindahl H, Rintala R, Sariola H, Louhimo I. Cervical Barrett’s esophagus: a common complication of gastric tube reconstruction. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:446-448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hamilton SR, Yardley JH. Regnerative of cardiac type mucosa and acquisition of Barrett mucosa after esophagogastrostomy. Gastroenterology. 1977;72:669-675. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Hoppo T, Badylak SF, Jobe BA. A novel esophageal-preserving approach to treat high-grade dysplasia and superficial adenocarcinoma in the presence of chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Surg. 2012;36:2390-2393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Procter DS. The ‘ink-well’ anastomosis in oesophageal reconstruction. S Afr Med J. 1967;41:187-190. [PubMed] |