Published online Dec 14, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17388

Revised: July 15, 2014

Accepted: August 13, 2014

Published online: December 14, 2014

Processing time: 287 Days and 6.3 Hours

AIM: To determine the prevalences of symptoms consistent with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and dyspepsia in South America.

METHODS: A telephone survey was conducted among adult owners of land-based telephones in São Paulo, Brazil, using previously validated computer-assisted sampling and survey protocols. The Portuguese-language survey included (1) sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., weight, height, smoking) and comorbidities; (2) dietary habits; (3) presence of symptoms consistent with GERD or dyspepsia within the prior 3 mo; and (4) use of medications and other therapies to manage symptoms. Data were stratified post-hoc into three homogeneous geographical regions of São Paulo according to the Social Exclusion Indices of the districts and postal codes. Survey response data from each respondent were weighted by the numbers of adults and landline telephones in each household. The analyses were weighted to account for sampling design and to be representative of the São Paulo population according to city census data.

RESULTS: Among 4570 households contacted, an adult from 3050 (66.7%) agreed to participate. The nonresponse rate was 33.3%. The mean (SE) respondent age was 42.6 (16.0) years. More than half of all respondents were women (53.1%), aged 18 through 49 years (66.7%), married or cohabitating (52.5%), and/or above normal-weight standards (i.e., 35.3% overweight and 16.3% obese). A total of 26.5% of women were perimenopausal. More than 20% of respondents reported highly frequent symptoms consistent with GERD (e.g., gastric burning sensation = 20.8%) or dyspepsia (e.g., abdominal swelling/distension = 20.9%) at least once per month. Prevalences of these symptoms were significantly (approximately 1.5- to 2.0-fold) higher among women than men but did not vary significantly as a function of advancing age. For instance, 14.1% of women reported that they experienced stomach burning (symptom of GERD) at least twice per week, compared to 8.4% of men (P = 0.012 by χ2 test). A total of 15.7% of women reported that they experienced abdominal swelling (symptom of dyspepsia) at least twice per week, compared to 6.4% of men (P < 0.001 by χ2 test). Despite frequent manifestations of GERD or dyspepsia, most (≥ 90%) respondents reported that they neither received prescription medications from physicians, nor took behavioral measures (e.g., dietary modifications), to manage symptoms.

CONCLUSION: Symptoms consistent with dyspepsia and GERD are prevalent in Brazil and represent major public-health and clinical challenges.

Core tip: Among residents of São Paulo responding to our survey, approximately 21% reported that they experienced highly frequent symptoms consistent with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or dyspepsia at least once per month in the prior 3 mo. Prevalences of these symptoms were significantly (about 1.5- to 2.0-fold) higher among women than men but did not vary significantly as a function of advancing age. Despite frequent manifestations of GERD or dyspepsia, most (≥ 90%) respondents reported that they neither received prescription medications from physicians, nor took behavioral measures (e.g., dietary modifications), to manage symptoms.

- Citation: Rosário Dias de Oliveira Latorre MD, Medeiros da Silva A, Chinzon D, Eisig JN, Dias-Bastos TR. Epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in Brazil (EpiGastro): A population-based study according to sex and age group. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(46): 17388-17398

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i46/17388.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i46.17388

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are common chronic conditions. These disorders can affect the entire gastrointestinal (GI) tract, with a large spectrum of symptoms in the absence of any identifiable organic causes. Dyspepsia, irritable-bowel syndrome, and constipation are examples of these disorders. On the other hand, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is an organic GI disorder that is typically more prevalent[1].

Both dyspepsia and GERD can reduce health-related quality of life[2-4], cause psychological distress[5], and/or impair sleep[6], activities of daily living, worker productivity[7-9], and leisure time. Dyspepsia is linked to an estimated 2 million visits to United States primary-care physicians and 40% of all United States gastroenterology referrals each year[10]. FGIDs also account for up to 50% of office time spent with patients by gastroenterologists[11].

Adverse consequences of these conditions are well documented[2,12]. As many as 1 in 5 North Americans experiences GERD. The point prevalence of GERD ranges from 0.1% to 5.0% in China; 5.1%-10.0% in Southern Europe; and 10.1%-15.0% in the United Kingdom and Sweden[12]. Incidences of GERD are comparatively low, including 5.4 per 1000 person-years in the United States and 4.5 per 1000 person-years in the United Kingdom[12,13]. The high ratio of prevalence to incidence of these conditions exemplifies their chronic nature[12] and may also be consistent with suboptimal management[14].

A telephone survey in Australia suggested that women more frequently experienced symptoms of dyspepsia (e.g., early satiety, bloating, nausea), whereas men more frequently experienced symptoms of GERD (e.g., regurgitation, heartburn)[4]. However, overall evidence concerning associations between gender, age (and other sociodemographic characteristics) and prevalences of self-reported GERD and dyspeptic symptoms is conflicting.

Limited data about symptoms consistent with GERD and dyspepsia are available for South America. Brazilian evidence-based consensus guidelines identified three key treatment objectives to manage GERD effectively: (1) resolve symptoms; (2) heal any mucosal lesions; and (3) prevent or minimize recurrent GERD and/or its complications[1]. According to these guidelines, many patients with GERD require counseling concerning the chronic nature of their condition and the need for long-term treatment adherence. However, limited information is available concerning the prevalences of self-reported symptoms of GERD and dyspepsia, as well as health-seeking behaviors, among Brazilian adults.

The chief purposes of this study were to: (1) estimate the prevalences of self-reported symptoms consistent with GERD and dyspepsia among adult inhabitants of São Paulo; and (2) investigate potential patient characteristics associated with these symptoms.

The study protocol was reviewed by an institutional Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Public Health of the University of São Paulo (FPH/USP). For telephone interviews, interviewers explained that participation was voluntary and that there would be neither any penalty for refusing to participate (or withdrawing consent) nor compensation for participating. Telephone respondents provided informed oral consent, and these were recorded. All data were held confidential, and interviewees were advised that they could communicate with the principal investigator (M.R.D.O.L.) or the FPH/USP Ethics Committee.

The study targeted adult inhabitants of São Paulo who owned landline telephones. A probabilistic sample was conducted using a computer-assisted telephone interviewing survey system. Potential respondents were categorized as to gender and age groups. Data were stratified post-hoc into three homogeneous geographical regions of São Paulo according to the Social Exclusion Indices of the districts and postal codes.

Sample size: The following algebraic expressions were used to determine the desired sample size:

n = n0•deff

n0 = (1 - P)/[P•cv2 (p)]

Where P denotes the prevalence of symptoms consistent with GERD or dyspepsia in the study population (estimated a priori at 20%); cv (p) signifies the maximum tolerated coefficient of variation when estimating the ratio in the sample (fixed at 17%); and deff is the design effect.

The deff value was fixed at 2. When contacting adults by landline, we used a raffle to determine which member of the household would be interviewed. The use of weights to compensate different probabilities of selecting each house member introduced a deff of 1.2. Further weights were introduced after stratification to minimize no-replies and noncoverage, leading to a deff of 1.6. Given a total deff of 2, we determined that 280 interviews were needed in each study domain. The smallest domain comprised men aged ≥ 50 years (10.8% of the adult population of São Paulo according to 2000 census data): 280/0.108 = 2592 (desired sample size rounds to 2600). Assuming a response rate of 85%, we needed to dial at least 3000 telephone numbers.

Further assuming that 30% of telephones would not be eligible, the total number of telephone numbers was conservatively estimated at 5000. To achieve the desired sample size, we used a systematic raffle of 10000 telephone listings in São Paulo, organized by area code and hence implicitly stratified by geographical region. Given the likelihood of nonresponses and ineligible telephones, we expected that 5000 telephone numbers would be reached for interviews after receiving a series of 25 first raffled replies. After discarding telephone numbers that did not correspond to homes or were inactive, we expected that the product of the proportions of telephones answered and of dwellers agreeing to participate in the survey would be 80%.

The questionnaire included four parts: (1) sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., weight, height, smoking) and comorbidities; (2) dietary habits; (3) presence of symptoms consistent with GERD or dyspepsia in the prior 3 mo, according to the Brazilian Consensus of GERD and Rome III definitions of each condition; and (4) use of medications and other therapies to manage symptoms. The survey required approximately 20 min for each interviewee to complete.

Interviewers were trained by a São Paulo field supervisor (M.R.D.O.L.) in November 2010. M.R.D.O.L. also served as a central authority to answer calls from interviewers in the field.

The interviewing software and survey instrument were developed and validated using two subsamples (50 individuals in each) of respondents. In a pilot study, the first 50 interviews were conducted initially by telephone, followed by face-to-face interviews in the household 2 to 7 d later. For the next 50 subjects, the sequence was reversed. The pilot study was conducted from November 23, 2010, through March 1, 2011. Validation of our survey data was based on the pilot-study findings of: (1) high agreement between interview modalities with regard to comorbidities (κ≥ 0.61; P < 0.001) and (2) no significant differences between mean age, body mass index (BMI), and the grade of evaluation of dietary quality (each P > 0.070) as reported by respondents across the two interview modalities. These items also showed high intraclass correlation coefficients (ricc > 0.78; P < 0.001).

A two-step data-weighting procedure was performed. The first step adjusted for different probabilities of selection among respondents, and the second (post-stratification) weighting step adjusted for imbalances caused by potential nonresponse and noncoverage bias between the study sample and population of São Paulo.

In the first step, data from each respondent were weighted by the numbers of adults and of landline telephones in each household. The second step further accounted for biases due to nonresponse and incomplete landline coverage by comparing distributions of the study sample population to distributions for the city of São Paulo according to age, gender, and educational level (10 population strata; Table 1). Population characteristics for São Paulo were obtained from the National Survey on Households (Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios [PNAD] População). This survey was conducted in 2008 by the Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE; http://www.ibge.gov.br).

| Characteristic | Study population | São Paulo population |

| Age, yr | ||

| 18-29 | 26.50 | 25.71 |

| 30-39 | 21.88 | 22.22 |

| 40-49 | 19.61 | 20.25 |

| 50-59 | 16.91 | 15.15 |

| ≥ 60 | 15.11 | 16.67 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 40.35 | 46.93 |

| Female | 59.65 | 53.07 |

| Educational level, yr | ||

| ≤ 8 | 36.02 | 42.88 |

| 9-11 | 41.64 | 35.41 |

| ≥ 12 | 22.34 | 21.71 |

Proportions of females and better-educated subjects (i.e., those with ≥ 9 or ≥ 12 school years) were higher in the EpiGastro population. In order to correct for these sample imbalances, post-stratification weights were adjusted. To calculate population weights, composite distributions per gender, age, and educational attainment (number of school years completed) were obtained for the São Paulo and EpiGastro populations across 18 categories for each population (9 categories for each gender within each population; Table 2). By computing ratios between values in the two populations across the 18 categories of gender, age, and educational level, post-stratification weights were generated (Table 3).

| Gender | Age, yr | Educational level, yr | |||||

| Study sample | São Paulo | ||||||

| ≤8 | 9-11 | ≥12 | ≤8 | 9-11 | ≥12 | ||

| Male | |||||||

| 18-39 | 0.035403 | 0.120343 | 0.049406 | 0.060640 | 0.115868 | 0.053637 | |

| 40-59 | 0.057332 | 0.051783 | 0.036460 | 0.085150 | 0.045360 | 0.034538 | |

| ≥ 60 | 0.036196 | 0.008190 | 0.008322 | 0.051568 | 0.009390 | 0.013051 | |

| Female | |||||||

| 18-39 | 0.044254 | 0.151651 | 0.083752 | 0.056661 | 0.124781 | 0.067006 | |

| 40-59 | 0.107266 | 0.072391 | 0.040026 | 0.100748 | 0.050135 | 0.038357 | |

| ≥ 60 | 0.079789 | 0.012021 | 0.005416 | 0.074009 | 0.008595 | 0.010505 | |

| Gender | Age, yr | Educational level, yr | ||

| ≤8 | 9-11 | ≥12 | ||

| Male | ||||

| 18-39 | 1.71285 | 0.96281 | 1.08564 | |

| 40-59 | 1.48523 | 0.87597 | 0.94728 | |

| ≥ 60 | 1.42470 | 1.14654 | 1.56820 | |

| Female | ||||

| 18-39 | 1.28037 | 0.82282 | 0.80006 | |

| 40-59 | 0.93924 | 0.69256 | 0.95830 | |

| ≥ 60 | 0.92757 | 0.71496 | 1.93950 | |

Final weights were computed by multiplying the designed weight by the post-stratification weight. Notably, there was only slight variation between the final weights. Coefficients of variation for the final weights were < 1%, suggesting that introduction of the population weights did not affect the overall accuracy of the results.

Descriptive statistics were generated for the sample characteristics. Correlations between symptoms consistent with GERD or dyspepsia by respondent gender or age were assessed using χ2 tests with a two-tailed α = 0.05 (a priori significance level of P < 0.05). Electronic data entry was supported by Delphi language (dbase). Statistical analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Version 14.0 for Windows (SPSS 14.0).

Among 4570 households contacted, one adult from 3050 (66.7%) agreed to participate in the survey. A total of 1344 (29.4%) of all individuals screened refused to participate before receiving any explanation of the survey, and a further 176 (3.9%) did so after receiving an explanation, for a nonresponse rate of 33.3%.

Overall characteristics: The mean (SE) age of the entire study population was 42.6 (16.0) years, and the median was 41.0. Most subjects were women (53.1%), aged 18 through 49 years (66.7%), and had never smoked (60.5%; Table 4). Majorities of respondents were married or cohabitating (52.5%). A total of 26.5% of women were perimenopausal. Slightly more than one-half (57.1%) of the study sample had some high-school or college education, and nearly one-half were employed (Table 4).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 1153 (46.9) |

| Female | 1875 (53.1) |

| Age group, yr | |

| 18-29 | 689 (25.0) |

| 30-49 | 1338 (41.7) |

| 50-59 | 498 (16.6) |

| 60-69 | 286 (10.0) |

| ≥ 70 | 217 (6.7) |

| Nutritional status2 | |

| Malnourished | 78 (2.6) |

| Normal | 1322 (45.8) |

| Overweight | 998 (35.3) |

| Obese | 466 (16.3) |

| Smoking | |

| Never | 1860 (60.5) |

| No, stopped | 675 (22.9) |

| Yes, < 10 cigarettes/d | 219 (7.0) |

| Yes, 10-20 | 216 (7.4) |

| Yes, > 20 | 58 (2.2) |

| Marital status3 | |

| Single | 1037 (35.8) |

| Married/RDP | 1520 (52.5) |

| Divorced | 220 (5.7) |

| Widowed | 239 (6.1) |

| Education | |

| ≤ 4th grade | 526 (19.2) |

| 5th-8th grades | 610 (23.7) |

| (in)Complete high school | 1209 (35.4) |

| (in)Complete college | 676 (21.7) |

| Employment status3 | |

| Employed | 1436 (48.6) |

| Self-employed | 382 (13.9) |

| Housewife | 450 (13.0) |

| Unemployed | 241 (8.4) |

| Other (not employed) | 474 (16.2) |

Nutritional status and dietary habits: Nearly half of the study population reported that they had normal nutritional status (45.8%), while slightly more than half were either overweight (35.3%) or obese (16.3%).

Daily consumption of fruit (40.2%), green vegetables (43.3%), or legumes (35.2%) was each reported by more than one-third of respondents. One-third or more consumed fruit (34.4%), green vegetables (33.7%), or legumes (41.3%) 2-4 d each week. On the other hand, 5%-7% of respondents reported that they never consumed the above food groups. Most respondents reported that they drank coffee every day (56.2%), whereas 29.2% never consumed coffee.

GI conditions and comorbidities: The most frequently reported GI condition (by ≥ 2% of respondents) was gastritis (19.0%), followed by GERD (6.1%), hemorrhoids (4.8%), irritable-bowel syndrome (3.1%), and ulcer (2.0%). Other GI comorbidities included esophagitis (1.9%), colitis (0.6%), diverticulitis (0.6%), ulcerative colitis (0.4%), anorexia/bulimia (0.1%), and Crohn’s disease (0.1%).

The most frequent non-GI complaint was headache (19.3%). Signs and symptoms of the following conditions were also recorded: hypertension (19.1%), depression (12.9%), diabetes (6.7%), thyroid disorder (5.2%), heart disease (4.9%), and asthma (3.5%).

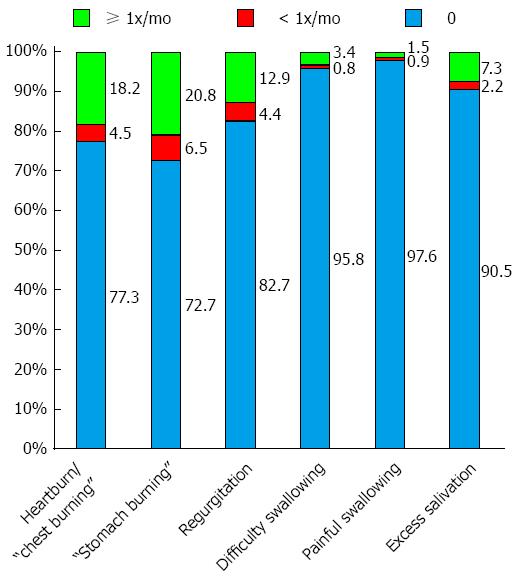

GERD: In all, 27.3% of respondents experienced a sensation of stomach burning: 20.8% at least once per month and 6.5% less frequently (Figure 1). Corresponding data for heartburn (or chest burning sensation), included 22.7% (total): 18.2% at least once monthly and 4.5% less frequently. A total of 17.3% of respondents reported regurgitation: 12.9% at least once monthly and 4.4% less frequently. Approximately 10% of subjects reported excessive salivation (i.e., sialorrrhea). Fewer than 5% of respondents reported difficulty swallowing (dysphagia; 4.2%) or painful swallowing (odynophagia; 2.4%).

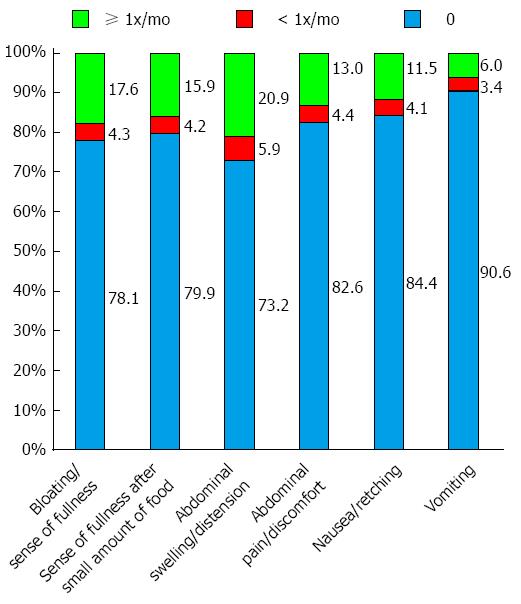

Dyspepsia: Abdominal swelling or distension was reported by 26.8% of survey participants: 20.9% at least once, and 5.9% less than once, monthly (Figure 2). Corresponding data for bloating/sensation of fullness were 21.9%, 17.6%, and 4.3%, respectively. More than 20% of respondents reported satiety after consuming a small amount of food: 15.9% at least once monthly and 4.2% less than once monthly. Fewer than 20% of respondents reported abdominal pain or discomfort (13.0% at least once monthly and 4.4% less than once monthly) or nausea (11.5% and 4.1%, respectively). Fewer than 10% of respondents (9.4%) reported vomiting, including 6.0% at least once monthly.

GERD by gender: Compared to their male counterparts, significantly higher (> 1.5-fold) frequencies of women reported most symptoms consistent with GERD occurring at least twice per week, including heartburn (P = 0.047), a sensation of stomach burning (P = 0.012), regurgitation (P < 0.001), difficulty swallowing (P = 0.012), and/or painful swallowing (P = 0.009 vs men by χ2 tests; Table 5).

| Male | Female | Total | P value | |

| Heartburn | ||||

| No | 1074 (92.3) | 1649 (87.5) | 2723 (89.8) | 0.047 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 79 (7.7) | 226 (12.5) | 305 (10.2) | |

| Sensation of stomach burning | ||||

| No | 1065 (91.6) | 1635 (85.9) | 2700 (88.6) | 0.012 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 88 (8.4) | 240 (14.1) | 328 (11.4) | |

| Regurgitation | ||||

| No | 1116 (96.7) | 1728 (91.4) | 2844 (93.9) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 37 (3.3) | 147 (8.6) | 184 (6.1) | |

| Difficulty swallowing | ||||

| No | 1136 (98.5) | 1827 (97.1) | 2963 (97.7) | 0.012 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 17 (1.5) | 48 (2.9) | 65 (2.3) | |

| Painful swallowing | ||||

| No | 1149 (99.6) | 1850 (98.6) | 2999 (99.1) | 0.009 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 4 (0.4) | 25 (1.4) | 29 (0.9) | |

| Excess salivation | ||||

| No | 1108 (96.0) | 1779 (94.7) | 2887 (95.3) | 0.274 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 45 (4.0) | 96 (5.3) | 141 (4.7) | |

GERD by age: No symptom of GERD correlated significantly with age groups (Table 6).

| Variable | 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | ≥70 | Total | P value |

| Heartburn | |||||||

| No | 624 (91.1) | 1182 (88.2) | 449 (88.4) | 259 (92.0) | 209 (94.5) | 2723 (89.8) | 0.152 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 65 (8.9) | 156 (11.8) | 49 (11.6) | 27 (8.0) | 8 (5.5) | 305 (10.2) | |

| Sensation of stomach burning | |||||||

| No | 612 (88.5) | 1176 (87.6) | 444 (86.9) | 261 (91.2) | 207 (95.2) | 2700 (88.6) | 0.067 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 77 (11.5) | 162 (12.4) | 54 (13.1) | 25 (8.8) | 10 (4.8) | 328 (11.4) | |

| Regurgitation | |||||||

| No | 650 (93.9) | 1261 (94.5) | 465 (93.3) | 264 (92.7) | 204 (93.1) | 2844 (93.9) | 0.847 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 39 (6.1) | 77 (5.5) | 33 (6.7) | 22 (7.3) | 13 (6.9) | 184 (6.1) | |

| Difficulty swallowing | |||||||

| No | 672 (97.6) | 1314 (98.1) | 490 (98.1) | 278 (96.8) | 209 (96.6) | 2963 (97.7) | 0.523 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 17 (2.4) | 24 (1.9) | 8 (1.9) | 8 (3.2) | 8 (3.4) | 65 (2.3) | |

| Painful swallowing | |||||||

| No | 681 (98.7) | 1326 (99.1) | 497 (99.9) | 282 (99.1) | 213 (98.3) | 2999 (99.1) | 0.160 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 8 (1.3) | 12 (0.9) | 1 (0.1) | 4 (0.9) | 4 (1.7) | 29 (0.9) | |

| Excess salivation | |||||||

| No | 666 (96.9) | 1264 (94.1) | 480 (96.3) | 269 (94.0) | 208 (96.4) | 2887 (95.3) | 0.095 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 23 (3.1) | 74 (5.9) | 18 (3.7) | 17 (6.0) | 9 (3.6) | 141 (4.7) | |

Most respondents (86.4%) reported that they used no medications that reduce GERD symptoms (Table 7). Among the minority of subjects who took medications, most used prescription medications (62.6% of those with “yes” responses about taking medications) or self-medicated (34.2%). The findings in Table 7 indicate that only about 14% of all respondents with available data used medications to manage GERD symptoms.

| Treatment | n (%) |

| Medication | |

| No | 2609 (86.4) |

| Yes: | 419 (13.6) |

| Prescribed by physician | 270 (62.6) |

| Self-medicated | 140 (34.2) |

| Recommended by family/friends | 5 (1.4) |

| Recommended by pharmacist | 9 (3.2) |

| Other therapies/measures | |

| No | 2932 (96.7) |

| Yes: | 96 (3.3) |

| Dietary changes or restrictions | 32 (32.8) |

| Herbal teas | 55 (57.4) |

| Other1 | 14 (14.7) |

The vast majority of respondents (96.7%) took no other measures, including dietary modification or consumption of herbal teas, to manage GERD symptoms.

Dyspepsia by gender: Significantly higher (> 2-fold) frequencies of women (vs men) reported that symptoms compatible with dyspepsia occurred at least twice weekly (Table 8). These included impaired digestion (P < 0.001 vs men), a sensation of postprandial gastric fullness after consuming a small amount of food (P < 0.001), abdominal swelling or distension (P < 0.001), and abdominal pain (P < 0.001). Nausea and vomiting occurring at least twice weekly were also significantly more frequent among women: 9.0% compared to 2.7% of men (P < 0.001) for nausea and 3.0% compared to 1.4%, respectively, for vomiting (P = 0.040 each by χ2 test).

| Variable | Male | Female | Total | P value |

| Impaired digestion | ||||

| No | 1094 (94.5) | 1615 (86.1) | 2709 (90.0) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 59 (5.5) | 260 (13.9) | 319 (10.0) | |

| Sensation of fullness1 | ||||

| No | 1094 (94.7) | 1652 (88.0) | 2746 (91.1) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 59 (5.3) | 223 (12.0) | 282 (8.9) | |

| Abdominal swelling | ||||

| No | 1081 (93.6) | 1578 (84.3) | 2659 (88.7) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 72 (6.4) | 297 (15.7) | 369 (11.3) | |

| Abdominal pain | ||||

| No | 1107 (95.9) | 1701 (90.6) | 2808 (93.1) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 46 (4.1) | 174 (9.4) | 220 (6.9) | |

| Nausea | ||||

| No | 1124 (97.3) | 1719 (91.0) | 2843 (94.0) | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 29 (2.7) | 156 (9.0) | 185 (6.0) | |

| Vomiting | ||||

| No | 1140 (98.6) | 1819 (97.0) | 2959 (97.8) | 0.040 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 13 (1.4) | 56 (3.0) | 69 (2.2) | |

Dyspepsia by age: No symptom consistent with dyspepsia correlated significantly with age groups (Table 9).

| Variable | 18-29 | 30-49 | 50-59 | 60-69 | ≥70 | Total | P value |

| Impaired digestion | |||||||

| No | 622 (90.6) | 1182 (89.5) | 437 (88.1) | 257 (88.6) | 211 (97.1) | 2709 (90.0) | 0.091 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 67 (9.4) | 156 (10.5) | 61 (11.9) | 29 (11.4) | 6 (2.9) | 319 (10.0) | |

| Sensation of fullness1 | |||||||

| No | 614 (89.7) | 1199 (90.3) | 463 (93.0) | 263 (92.7) | 207 (95.0) | 2746 (91.1) | 0.361 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 75 (10.3) | 139 (9.7) | 35 (7.0) | 23 (7.3) | 10 (5.0) | 282 (8.9) | |

| Abdominal swelling | |||||||

| No | 609 (88.8) | 1161 (87.8) | 429 (87.7) | 255 (89.9) | 205 (94.7) | 2659 (88.7) | 0.445 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 80 (11.2) | 177 (12.2) | 69 (12.3) | 31 (10.1) | 12 (5.3) | 369 (11.3) | |

| Abdominal pain | |||||||

| No | 638 (93.0) | 1232 (92.5) | 463 (93.6) | 267 (93.9) | 208 (95.4) | 2808 (93.1) | 0.742 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 51 (7.0) | 106 (7.5) | 35 (6.4) | 19 (6.1) | 9 (4.6) | 220 (6.9) | |

| Nausea | |||||||

| No | 643 (92.8) | 1245 (93.6) | 478 (95.8) | 267 (93.0) | 210 (97.6) | 2843 (94.0) | 0.227 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 46 (7.2) | 93 (6.4) | 20 (4.2) | 19 (7.0) | 7 (2.4) | 185 (6.0) | |

| Vomiting | |||||||

| No | 667 (97.0) | 1308 (98.1) | 489 (97.8) | 281 (97.8) | 214 (98.5) | 2959 (97.8) | 0.660 |

| ≥ 2x/wk | 22 (3.0) | 30 (1.9) | 9 (2.2) | 5 (2.2) | 3 (1.5) | 69 (2.2) | |

Most respondents used no medications that reduce dyspeptic symptoms (88.9%; Table 10). Of the minority (11.1%) who did, most reported that they received prescriptions from their physicians (57.4%) or self-medicated (40.8%). Most survey participants also reported that they did not use other, nonpharmacologic interventions (96.0%). Among the minority of respondents who did, 65.5% used herbal teas and 25.5% modified their diets.

| Treatment | n (%) |

| Medication | |

| No | 2668 (88.9) |

| Yes: | 360 (11.1) |

| Prescribed by physician | 206 (57.4) |

| Self-medicated | 148 (40.8) |

| Recommended by pharmacist | 11 (2.7) |

| Recommended by family/friends | 7 (1.9) |

| Other therapies/measures | |

| No | 2890 (96.0) |

| Yes: | 138 (4.0) |

| Dietary changes or restrictions | 31 (25.5) |

| Herbal teas | 91 (65.5) |

| Other1 | 18 (11.6) |

Approximately 20% of EpiGastro survey respondents reported highly frequent symptoms consistent with dyspepsia or GERD, yet most (about 90%) respondents did not receive medications and/or use other measures to manage symptoms. Symptoms were reported significantly more frequently by women than men. Frequencies of self-reported GI symptoms did not vary significantly as a function of age.

These results are broadly consistent with findings from a survey of individuals at least 16 years of age in 22 Brazilian cities[15], in which 4.6% of respondents reported heartburn symptoms and 7.3% GERD. Paralleling our data, prevalences of heartburn and GERD were higher in females than males. Another study, in Southern Brazil, found an approximately 50% higher prevalence of dyspeptic symptoms in women than men[16].

A retrospective review of 1021 subjects in Mexico City demonstrated that 41 (4.0%) persons had dyspepsia according to Rome II criteria[17]. Among these individuals, 85.4% were women and 14.6% men (P < 0.001). Among the dyspepsia subgroup, 85.0% of women reported ulcer-like symptoms (vs 15.0% of men) and 83.3% reported dysmotility-like symptoms (vs 16.7% of men). On the other hand, 33.3% of men considered the best description of their dyspepsia to be nausea (vs 2.9% of women), and 16.7% of men reported frequent vomiting (vs 0 women; P = 0.0014)[17].

Dysmotility-like symptoms may result from heightened sensitivity of visceral afferents, potentially in tandem with autonomic dysregulation, in women[18,19]. In fact, women may process or encode noxious visceral stimuli differently from men, and these differences may be modulated by 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptors of the amygdala and prefrontal cortex in central pain-processing networks and also by female reproductive hormones[18,20-23]. Some studies have challenged the hypothesis of enhanced visceral pain perception in women, however[24]. Gender role socialization may also contribute to a female proclivity for reporting dyspepsia, as women may find it more socially acceptable (vs men) to report this condition’s painful or distressing abdominal symptoms[25].

A previous, North American telephone survey of 21,128 adults concerning upper GI symptoms found that heartburn was the most commonly reported condition (by 6.3% of respondents)[7]. In this study, the most frequent symptom reported at least once monthly was early satiety, in 23.0% of respondents: 25.8% of women and 20.1% of men. Of respondents reporting frequent GI symptoms, nearly twice as many women (n = 2558; 28.2%) reported bloating (n = 1170; 12.9%), nausea (n = 1082; 11.9%), or vomiting (n = 306; 3.4%) compared to 1445 (17.2%) men reporting these symptoms: bloating (n = 699; 8.3%), nausea (n = 573; 6.8%), or vomiting (n = 173; 2.1%). Among all respondents reporting clinically relevant GI symptoms with any frequency, about twice as many women as men reported bloating [n = 505 (2.9%) vs n = 289 (1.7%)], postprandial fullness [n = 364 (2.1%) vs n = 261 (1.5%)], or early satiety [n = 609 (3.5%) vs n = 315 (1.8%)]. On the other hand, proportions of respondents with heartburn, regurgitation, or dysphagia were more similar between genders[7].

Overall, however, evidence concerning a female gender proclivity for dyspepsia and GERD is conflicting, as are population data associating advancing age with the prevalences of these conditions[4,12,15-18,24,26]. In terms of age, epidemiologic data are quite mixed[27-31]. Two studies found an increased prevalence of GERD with advancing age, but the trend reversed at later ages[13,32]. In the previously cited Brazilian study of 22 cities, the prevalence of GERD increased as a function of advancing age, from 51.4% of those aged 16 to 25 years to 73.8% of those aged > 55[15]. However, the prevalence of heartburn appeared to decrease with age. Another, southern Brazilian cross-sectional population study using Rome criteria suggested that the prevalence of frequent dyspepsia (and specifically dysmotility-type dyspepsia) decreased with advancing age from the decade of 20-29 to ≥ 70 years[16].

A study of 1476 residents of Malmö, Sweden (mean age = 49.9 years) that dichotomized its population found similar prevalences of reflux symptoms in those aged ≤ 40 or > 40 years[33]. One limitation of these population-based studies is that they are based on subjective symptoms rather than other, objective signs, such as reflux esophagitis, which may be more severe and/or frequent in elderly patients[12].

Concerning gender, one longitudinal study and four cross-sectional studies examined the influence of sex on GERD symptoms, and found no significant association[12,28-31]. On the other hand, many of these studies did not include pregnant women, who experienced GERD symptoms more frequently than men in one study, as did smokers and overweight individuals[31].

In this context, previous research found an interaction between age, habitus, and GERD. Our study included 53.1% women, and 51.6% of all respondents reported that they were overweight or obese.

In a prior study, women with body mass index (BMI) values above 35 kg/m2 had a more than 6-fold increased relative risk of GERD (OR = 6.3; 95%CI: 4.9-8.0) compared to their counterparts with a BMI below 25 kg/m2[34]. After adjustment for increasing BMI, endogenous female reproductive hormone levels were not associated with GERD, in another study[35].

Regarding other behavioral risk factors, approximately 83% of our study population did not smoke, and 45%-58% of respondents reported that they consumed coffee (58%), green vegetables (55%), legumes (45%), and/or fruit (49%) at least 5 d per week. Exposure to citrus fruits and fruit juices can precipitate GERD via excess gastric acid or non-acid mechanisms. Overall, most behavioral risk factors apart from obesity do not seem to have a strong influence on incidences of GERD and dyspepsia, although cigarette smoking may be most strongly associated as a trigger of GERD (particularly in men[36])[12,29-31,37].

Our results might underestimate total numbers and frequencies of patients with symptoms of dyspepsia and GERD, and also overestimate medication use, compared to the general population. First, higher proportions of individuals who agree to participate in surveys may be more health conscious, better educated, more financially resourceful, and/or more likely to seek and receive care to minimize chronic illnesses compared to those refusing to participate (i.e., effects of selection bias)[38].

Second, the EpiGastro study included only residences with landline telephones. Homes lacking landlines may be less economically advantaged, and their occupants may have worse self-rated health[39]. In an Australian study, men and women with low socioeconomic status reported a significantly increased relative risk of upper dysmotility syndromes compared to their counterparts in the upper four quintiles[40].

Third, our study did not capture data from São Paulo residents who used cellular telephones.

As a group, United States residents who exclusively use cell phones are disproportionately male, single, mobile, young, and residing in rental housing, according to one study[41]. On average, cell-only adults more frequently engage in risky health behaviors (e.g., smoking, binge drinking), experience financial difficulties in obtaining regular health care, and yet report superior health status[42,43]. A previous Brazilian study found that young people with low incomes were more affected by symptoms of dyspepsia[16]. Prevalences of GERD have also been associated with reduced educational attainment in other societies[27,44,45].

Fourth, as low as we found the proportions of all respondents receiving prescription medications (≤ 9%), these data may have overestimated actual prescription use because participants in telephone surveys may be less likely than nonparticipants to report adverse health-seeking behaviors, such as not having health insurance or not receiving or using prescription medications. Fifth and finally, additional surveys need to be carried out in different geographic and social settings. Asian studies have found that the prevalence of symptomatic GERD and consultations for dyspepsia were significantly higher in rural (vs urban and/or suburban) residents[26,46].

Our a posteriori weighting and mixed-mode survey design may have helped to limit noncoverage and other forms of bias. By telephone company estimates performed for our survey, more than three-quarters of our target population owned landlines. A previous Brazilian study determined that a minimum landline coverage of 70% (in Southern and Central-West metropolitan areas) was necessary to avoid coverage bias[47]. One other potential bias is that most of our survey participants were women, who are more likely (vs men) to respond to health surveys in general, report physical symptoms, seek medical attention for constipation, and use laxatives to manage symptoms[48-50]. Women also seek medical consultation for dyspepsia more frequently than men in some societies[18,51,52].

The participation rate (67%) was acceptable. In one of the largest epidemiologic studies of upper GI disorders performed by telephone, the complete-survey nonresponse rate exceeded our rate of 33%[7]. Telephone surveys typically have higher nonresponse rates than household surveys[53]. Caller identification mechanisms tend to screen out younger and/or unmarried adults, members of ethno-racial minorities, and homes with young children[54]. Given its cross-sectional nature, our study also could not provide context as to the natural history of symptoms consistent with dyspepsia or GERD, or accurately account for waxing and waning symptoms over time. Development of intercurrent illnesses can influence patients’ GI symptom recall[5]. However, the survey reference interval of 3 mo used in our study was shorter than recall intervals employed in a number of other telephone surveys[12], potentially limiting recall bias.

On the other hand, it is somewhat concerning that only about 6% of our respondents reported physician diagnoses of GERD, yet more frequently reported symptoms compatible with such diagnoses. This disparity may reflect limited access to care (among members of lower-socioeconomic strata) and the fact that symptoms of dyspepsia and GERD often go unreported to, and/or uninvestigated by, physicians. An estimated 48% of cases of dyspepsia are uninvestigated in Brazil[55]. In other (US) populations, 75% of patients with FGIDs never consult with physicians[56].

In conclusion, approximately 21% of respondents from São Paulo reported highly frequent symptoms consistent with GERD (e.g., gastric burning sensation = 20.8%) or dyspepsia (e.g., abdominal swelling/distension = 20.9%). However, most respondents did not report that they had received diagnoses of these conditions, or medications to manage them, from their physicians. Women were significantly (approximately 1.5- to 2-fold) more likely to report symptoms of GERD and dyspepsia than men, but there was no significant association between advancing age and self-reported symptoms of these conditions. Further research is needed to assess the potential effects of these disorders on daily activities, diet, sleep, and worker productivity.

Assistance in manuscript preparation was provided by Stephen W. Gutkin, Rete Biomedical Communications Corp. (Wyckoff, NJ, United States).

Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and dyspepsia are distressing to many patients and often erode their quality of life. Ratios of prevalence to incidence of GERD are high and hence consistent with this condition’s chronic nature and potentially suboptimal management.

Limited data are available concerning the prevalences of self-reported symptoms consistent with GERD and dyspepsia in Brazil, particularly within the city of São Paulo.

Some telephone surveys have revealed that women more frequently experience symptoms of dyspepsia, whereas men more frequently experience symptoms of GERD. Overall, however, studies differ concerning associations between gender, age (and other sociodemographic characteristics) and prevalences of self-reported GERD and dyspepsia. Data are limited regarding self-reported symptoms of these conditions, and measures taken to manage them, among persons in South America.

By conducting telephone and face-to-face surveys of individuals in São Paulo concerning symptoms of GERD and dyspepsia, as well as measures taken to manage them, this study may help to further delineate the public-health dimensions and clinical challenges presented by these chronic conditions. Observations of substantial frequencies of self-reported symptoms of GERD and dyspepsia, coupled with low overall frequencies of medication use and/or lifestyle modification to manage these conditions, might suggest an unmet need in this urban Brazilian population.

GERD is an organic disorder characterized by symptoms of gastric-acid reflux, whereas dyspepsia is a “functional,” upper gastrointestinal condition characterized by abdominal distension and other forms of discomfort.

This manuscript “Epidemiology of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in Brazil (EpiGastro): A population-based study according to sex and age group” is a very interesting article.

P- Reviewer: Fett JD S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: A E- Editor: Ma S

| 1. | Moraes-Filho JP, Navarro-Rodriguez T, Barbuti R, Eisig J, Chinzon D, Bernardo W. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease: an evidence-based consensus. Arq Gastroenterol. 2010;47:99-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tack J, Becher A, Mulligan C, Johnson DA. Systematic review: the burden of disruptive gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on health-related quality of life. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;35:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Aro P, Talley NJ, Agréus L, Johansson SE, Bolling-Sternevald E, Storskrubb T, Ronkainen J. Functional dyspepsia impairs quality of life in the adult population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:1215-1224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Westbrook JI, Talley NJ, Westbrook MT. Gender differences in the symptoms and physical and mental well-being of dyspeptics: a population based study. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:283-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bryant RV, van Langenberg DR, Holtmann GJ, Andrews JM. Functional gastrointestinal disorders in inflammatory bowel disease: impact on quality of life and psychological status. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:916-923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Mody R, Bolge SC, Kannan H, Fass R. Effects of gastroesophageal reflux disease on sleep and outcomes. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:953-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Camilleri M, Dubois D, Coulie B, Jones M, Kahrilas PJ, Rentz AM, Sonnenberg A, Stanghellini V, Stewart WF, Tack J. Prevalence and socioeconomic impact of upper gastrointestinal disorders in the United States: results of the US Upper Gastrointestinal Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:543-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 277] [Cited by in RCA: 274] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gisbert JP, Cooper A, Karagiannis D, Hatlebakk J, Agréus L, Jablonowski H, Nuevo J. Impact of gastroesophageal reflux disease on work absenteeism, presenteeism and productivity in daily life: a European observational study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wahlqvist P, Reilly MC, Barkun A. Systematic review: the impact of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease on work productivity. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:259-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Frank L, Kleinman L, Ganoczy D, McQuaid K, Sloan S, Eggleston A, Tougas G, Farup C. Upper gastrointestinal symptoms in North America: prevalence and relationship to healthcare utilization and quality of life. Dig Dis Sci. 2000;45:809-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chang JY, Locke GR, McNally MA, Halder SL, Schleck CD, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Impact of functional gastrointestinal disorders on survival in the community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:822-832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dent J, El-Serag HB, Wallander MA, Johansson S. Epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2005;54:710-717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1256] [Cited by in RCA: 1261] [Article Influence: 63.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ruigómez A, García Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Graffner H, Dent J. Natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease diagnosed in general practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:751-760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Bytzer P. What makes individuals with gastroesophageal reflux disease dissatisfied with their treatment? Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:816-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moraes-Filho JP, Chinzon D, Eisig JN, Hashimoto CL, Zaterka S. Prevalence of heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux disease in the urban Brazilian population. Arq Gastroenterol. 2005;42:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | de Oliveira SS, da Silva dos Santos I, da Silva JF, Machado EC. [Prevalence of dyspepsia and associated sociodemographic factors]. Rev Saude Publica. 2006;40:420-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schmulson M, Adeyemo M, Gutiérrez-Reyes G, Charúa-Guindic L, Farfán-Labonne B, Ostrosky-Solis F, Díaz-Anzaldúa A, Medina L, Chang L. Differences in gastrointestinal symptoms according to gender in Rome II positive IBS and dyspepsia in a Latin American population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:925-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ahlawat SK, Cuddihy MT, Locke GR. Gender-related differences in dyspepsia: a qualitative systematic review. Gend Med. 2006;3:31-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Schmulson MJ, Mayer EA. Gastrointestinal sensory abnormalities in functional dyspepsia. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;12:545-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mayer EA, Naliboff B, Lee O, Munakata J, Chang L. Review article: gender-related differences in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1999;13 Suppl 2:65-69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Barsky AJ, Peekna HM, Borus JF. Somatic symptom reporting in women and men. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:266-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 449] [Cited by in RCA: 460] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Heitkemper MM, Jarrett M. Gender differences and hormonal modulation in visceral pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2001;5:35-43. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Lamberg L. Venus orbits closer to pain than Mars, Rx for one sex may not benefit the other. JAMA. 1998;280:120-124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chang L, Toner BB, Fukudo S, Guthrie E, Locke GR, Norton NJ, Sperber AD. Gender, age, society, culture, and the patient’s perspective in the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1435-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 258] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gijsbers van Wijk CM, van Vliet KP, Kolk AM, Everaerd WT. Symptom sensitivity and sex differences in physical morbidity: a review of health surveys in the United States and The Netherlands. Women Health. 1991;17:91-124. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Wang JH, Luo JY, Dong L, Gong J, Tong M. Epidemiology of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a general population-based study in Xi’an of Northwest China. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:1647-1651. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1900-1920; quiz 1943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2368] [Cited by in RCA: 2453] [Article Influence: 129.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 28. | Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1448-1456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1488] [Cited by in RCA: 1380] [Article Influence: 49.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Locke GR, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ. Risk factors associated with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Med. 1999;106:642-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Mohammed I, Cherkas LF, Riley SA, Spector TD, Trudgill NJ. Genetic influences in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a twin study. Gut. 2003;52:1085-1089. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Isolauri J, Laippala P. Prevalence of symptoms suggestive of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease in an adult population. Ann Med. 1995;27:67-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kotzan J, Wade W, Yu HH. Assessing NSAID prescription use as a predisposing factor for gastroesophageal reflux disease in a Medicaid population. Pharm Res. 2001;18:1367-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Wiklund I, Carlsson J, Vakil N. Gastroesophageal reflux symptoms and well-being in a random sample of the general population of a Swedish community. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:18-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Obesity and estrogen as risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. JAMA. 2003;290:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Menon S, Prew S, Parkes G, Evans S, Smith L, Nightingale P, Trudgill N. Do differences in female sex hormone levels contribute to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;25:772-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Matsuki N, Fujita T, Watanabe N, Sugahara A, Watanabe A, Ishida T, Morita Y, Yoshida M, Kutsumi H, Hayakumo T. Lifestyle factors associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:340-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Chithra P, Chandrikha C, Kannan AS, Srinath S, Srinivasan V, Jayanthi V. Clinical and life style variables in functional dyspepsia and its sub-types. Trop Gastroenterol. 2012;33:33-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Cook LS, White JL, Stuart GC, Magliocco AM. The reliability of telephone interviews compared with in-person interviews using memory aids. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:495-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ford ES. Characteristics of survey participants with and without a telephone: findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:55-60. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Bytzer P, Howell S, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Low socioeconomic class is a risk factor for upper and lower gastrointestinal symptoms: a population based study in 15 000 Australian adults. Gut. 2001;49:66-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lee S, Brick JM, Brown ER, Grant D. Growing cell-phone population and noncoverage bias in traditional random digit dial telephone health surveys. Health Serv Res. 2010;45:1121-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Blumberg SJ, Luke JV, Cynamon ML. Telephone coverage and health survey estimates: evaluating the need for concern about wireless substitution. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:926-931. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Blumberg SJ, Luke JV. Coverage bias in traditional telephone surveys of low-income and young adults. Public Opinion Q. 2007;71:734-749. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 44. | El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, Graham DY, Richardson P, Genta RM, Rabeneck L. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692-1699. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Diaz-Rubio M, Moreno-Elola-Olaso C, Rey E, Locke GR, Rodriguez-Artalejo F. Symptoms of gastro-oesophageal reflux: prevalence, severity, duration and associated factors in a Spanish population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:95-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mahadeva S, Yadav H, Everett SM, Goh KL. Factors influencing dyspepsia-related consultation: differences between a rural and an urban population. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;23:846-853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bernal R, Silva NN. Home landline telephone coverage and potential bias in epidemiological surveys. Rev Saude Publica. 2009;43:421-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Gálvez C, Garrigues V, Ortiz V, Ponce M, Nos P, Ponce J. Healthcare seeking for constipation: a population-based survey in the Mediterranean area of Spain. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:421-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pare P, Ferrazzi S, Thompson WG, Irvine EJ, Rance L. An epidemiological survey of constipation in Canada: definitions, rates, demographics, and predictors of health care seeking. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3130-3137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 305] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | van Wijk CM, Kolk AM. Sex differences in physical symptoms: the contribution of symptom perception theory. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:231-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 304] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Jones R, Lydeard S. Dyspepsia in the community: a follow-up study. Br J Clin Pract. 1992;46:95-97. [PubMed] |

| 52. | Jones RH, Lydeard SE, Hobbs FD, Kenkre JE, Williams EI, Jones SJ, Repper JA, Caldow JL, Dunwoodie WM, Bottomley JM. Dyspepsia in England and Scotland. Gut. 1990;31:401-405. [PubMed] |

| 53. | Diehr P, Koepsell TD, Cheadle A, Psaty BM. Assessing response bias in random-digit dialling surveys: the telephone-prefix method. Stat Med. 1992;11:1009-1021. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Kempf AM, Remington PL. New challenges for telephone survey research in the twenty-first century. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:113-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Sander GBML, Francesconi MH, Lopes MHI, Madi J. Unexpected high prevalence of non-investigated dyspepsia in Brazil: a population-based study [abstract]. Gut. 2007;56:A195. |

| 56. | Talley NJ. Functional gastrointestinal disorders as a public health problem. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20 Suppl 1:121-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |