Published online Nov 28, 2014. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16774

Revised: August 4, 2014

Accepted: September 29, 2014

Published online: November 28, 2014

Processing time: 185 Days and 2.7 Hours

Acute liver failure is a rare presentation of hematologic malignancy. Acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) is a newly recognized clinical entity that describes acute hepatic decompensation in persons with preexisting liver disease. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is an aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) with increasing incidence in older males, females and blacks. However, it has not yet been reported, to present with acute liver failure in patients with preexisting chronic liver disease due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) co-infection. We describe a case of ACLF as the presenting manifestation of DLBCL in an elderly black man with HIV/HCV co-infection and prior Hodgkin’s disease in remission for three years. The rapidly fatal outcome of this disease is highlighted as is the distinction of ACLF from decompensated cirrhosis. Due to the increased prevalence of HIV/HCV co-infection in the African American 1945 to 1965 birth cohort and the fact that both are risk factors for chronic liver disease and NHL we postulate that the incidence of NHL presenting as ACLF may increase.

Core tip: Recognition of acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) is vital because it may be rapidly fatal. However, many patients have underlying silent liver disease, especially, hepatitis C virus (HCV) cirrhosis. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is an aggressive lymphoma which is beginning to occur more frequently in the same race and birth cohort as HCV/human immunodeficiency virus related liver disease. Early recognition and potential treatment of this rapidly fatal lymphoma depends on a high index of suspicion. Due to the shared demographics the incidence of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as ACLF is likely to increase.

- Citation: Siba Y, Obiokoye K, Ferstenberg R, Robilotti J, Culpepper-Morgan J. Case report of acute-on-chronic liver failure secondary to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(44): 16774-16778

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v20/i44/16774.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v20.i44.16774

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a well-defined clinical syndrome with associated high mortality. Acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) is also a rare syndrome with diverse etiology and high mortality which is less well-defined or understood. Of the 1147 adults studied in the adult ALF Study Group, less than seven percent were due to malignancy[1]. Neither the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), nor the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) listed malignancy as a potential precipitant of ACLF. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in the United States[2,3]. Incidence rates for NHL have been increasing 3%-4% per year from 1973 to the 1990s especially among older males, females, and blacks[3]. We present a rapidly fatal case of DLBCL presenting as ACLF in an elderly black man with HIV/HCV co-infection.

A 71- year- old African American man was brought to our emergency department (ED) by a friend who noted that he was becoming increasingly confused and lethargic. He was a former intravenous drug user now on methadone maintenance. The patient had a history of HIV/HCV co-infection (CD4 count of 116 and viral load of 214 copies/mL). Liver biopsy two years prior to admission revealed grade 2 inflammation with stage 1 fibrosis. He also reported a history of Hodgkin’s disease that was now in remission after chemo-radiotherapy three years prior.

The patient was afebrile and jaundiced. Firm non-tender diffusely enlarged right cervical and axillary lymph nodes approximately 3 cm × 3 cm were noted. Heart and lung examinations were unremarkable. The abdomen was not distended. The liver and spleen were not palpable. There was no ascites. He was oriented only to self and month of the year. He was somnolent but had no asterexis. Capillary glucose was 46 mg/dL in the ED. His mental status did not improve after correction of hypoglycemia and naloxone administration.

Laboratory results showed a normal white blood cell (WBC) count, 8.7 × 109/L, hemoglobin, 9.6 g/dL, hematocrit, 27.9% and platelet count 96000 per microliter of blood. His platelet count one month prior to admission was 161000. He was mildly azotemic, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 25 mg/dL, and serum creatinine 1.2 mg/dL. Liver tests revealed aspartate aminotransferase (AST) of 145 IU/L (normal range: 15-37 IU/L), alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 39 IU/L (normal range: 12-78 IU/L), Alkaline phosphatase 221 IU/L (normal range: 50-136 IU/L), total bilirubin 7.3 mg/dL (normal range: 0.2-1.2 mg/dL), direct bilirubin 6.0 mg/dL (normal range: 0.0-0.2 mg/dL), total protein 5.5 g/dL (normal range: 6.4-8.2 g/dL) and albumin 2.5 g/dL (normal range: 3.4-5 g/dL). International normalized ratio (INR) was 1.6. Arterial blood gas on room air revealed pH of 7.46, pCO2 30 mmHg, pO2 65 mmHg, HCO3- 21 mmol/L, and lactate of 4.1 mmol/L (normal range: 0.5-1.6 mmol/L). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) was 732 IU/L (normal range: 118-273 IU/L), serum alcohol level was < 3 mg/dL and urine toxicology was positive for opiates and methadone. Acetaminophen, hepatitis A and B serologies, ceruloplasmin, and ANA were all within normal limits.

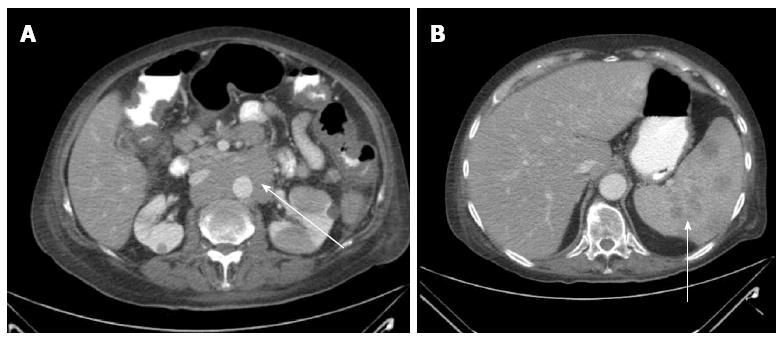

Abdominal sonogram showed fatty liver infiltration, mild splenomegaly, mildly distended gallbladder without calculi, and no biliary ductal dilatation. Abdominal computed tomography with contrast showed multiple hypodense splenic lesions, a confluent non-compressing circumaortic mass, multiple para-aortic and pelvic lymph nodes, and bilateral pulmonary nodules (largest 1 cm) (Figure 1).

Right axillary lymph node excision biopsy revealed a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. The patient’s liver tests continued to worsen with ALT 37 IU/L, AST 218 IU/L, maximum total bilirubin of 10 mg/dL, (direct bilirubin 8.9 mg/dL), and INR of 2.2. Hemoglobin and hematocrit remained unchanged at 9.7 g/dL and 23.4% respectively at discharge. He was transferred to another facility for chemotherapy. There he spent an additional week, received one cycle of chemotherapy but due to continued deterioration family requested comfort care. He was transferred to a hospice facility where he died a week later.

Our patient is the first reported case of rapidly fatal DLBCL in a patient with chronic liver disease due to HCV/HIV coinfection. Because of the presence of inflammation and fibrosis on an earlier biopsy this is a presentation of ACLF and not ALF. Although ALF has been well defined, a universally accepted definition for ACLF is still a subject of debate and on-going research[4,5]. This is due to the heterogeneous proposed etiology, pathophysiology, organ dysfunction, and outcomes in different regions of the world.

ALF refers to the acute (< 26 wk) onset of severe liver injury with encephalopathy and impaired synthetic function (INR ≥ 1.5) in a patient without pre-existing liver disease[1]. APASL defined ACLF as an acute hepatic insult manifesting with jaundice (bilirubin > 5mg/dL) and coagulopathy (INR > 1.5), complicated within four weeks by ascites and/or encephalopathy in a patient with previously diagnosed or undiagnosed chronic liver disease. This definition fits our patient. An AASLD/EASL consensus statement defined ACLF as a syndrome among a subgroup of cirrhotic patients who develop organ failure following hospital admission with or without an identifiable precipitating event and have increased mortality rates. The differences in the above definitions are highlighted in Table 1[4,5].

| APASL definition | AASLD/EASL consensus | |

| Duration between insult and ACLF | 4 wk | Not defined |

| Duration in which there is higher mortality | Not defined | 3 mo |

| What qualifies as “chronic liver disease” | Chronic liver disease with/without only compensated cirrhosis | Only cirrhosis, including those with prior decompensation |

| What qualifies as precipitants? | ||

| Alcohol, drugs, hepatotropic viruses, surgery, trauma | Yes | Yes |

| Sepsis | No | Yes |

| Variceal bleeding | No consensus | Yes |

One particularly contentious issue is “what exactly qualifies as chronic liver disease?” For the purposes of ACLF, the APASL consensus definition for chronic liver disease included patients with compensated cirrhosis of any etiology, chronic hepatitis, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, cholestatic liver disease, and metabolic liver disease. Simple steatosis was excluded because it is not always progressive. Decompensated cirrhosis on the other hand was also excluded because it is a distinct clinical entity that is irreversible whereas ALF and ACLF have potentially reversible acute insults. Again, our patient with mild HCV/HIV inflammation and fibrosis fits this description. However, per EASL/AASLD only cirrhotics, including subjects with prior decompensation qualify as “chronic liver disease” because these patients have distinctly different immune and cardiovascular response to injury.

The precipitating factors of ACLF may be either hepatic or extra-hepatic in origin. Hepatic causes include alcoholic hepatitis, acute viral hepatitis (HAV, HBV, and HEV), drug-induced liver injury, portal vein thrombosis, acute auto-immune hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, and ischemic hepatitis. Extra-hepatic insults comprise bacterial or fungal infections, variceal hemorrhage, surgery, trauma, and unknown hepatotoxins[6]. A case of Hodgkin’s lymphoma induced - ACLF in an HBV patient has been reported. In that report the patient developed acute on chronic hepatitis B following treatment with entecavir. Post-mortem findings revealed co-existent early Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HL)[7]. Our patient had ACLF secondary to DLBCL which is a NHL.

HL and NHL are two distinct hematologic malignancies. HL spreads in a contiguous manner via the lymphatic system and is characterized on hematoxylin and eosin stain by Reed-Sternberg cells which are transformed EBV positive cells in a background of granulocytes, plasma cells, and lymphocytes. DLBCL is the most common type of NHL. NHL represents 4.2% of all new cancer cases in the United States. It is the seventh most common cancer and seventh leading cause of cancer deaths. It refers to a constellation of disorders with heterogeneous clinico-pathologic features distinguished by a diffuse effacement of architecture composed mainly of large B-cells in different stages of maturation. It is an aggressive lymphoma that commonly arises from peripheral lymph nodes presenting with painless, rubbery lymphadenopathy sometimes with constitutional symptoms such as fever, night sweats, and unintentional weight loss. Several extra-nodal sites including but not limited to the bone marrow, gastrointestinal tract, brain, thyroid, testes, skin, and breast are also sites of initial presentation[2,8,9].

About 40 cases of ALF due to any lymphoma or leukemia have been published since 1952[10,11]. Due to its rarity it is mostly under-recognized and a high degree of clinical suspicion is required. NHL is traditionally considered to be common in those above 70 years of age, males, whites, family clusters, and is associated with chronic viral infections such as Ebstein Bar Virus, HIV, HBV, and HCV. Nevertheless, the strongest predictor of risk is immune system abnormality[3,9]. Our patient’s risk factors for NHL include male sex, advanced age, HIV/AIDS, HCV, prior Hodgkin’s and chemo-radiotherapy.

HCV is strongly associated with the occurrence of NHL in endemic areas such as Italy, Japan, and Egypt, but not in North America. Several oncogenic mechanisms have been proposed to explain the development of NHL in patients with chronic HCV such as: chronic antigen stimulation leading to monoclonal malignant proliferation; HCV genetic damage to B-cell tumor suppressor genes; HCV replication within B cells inducing oncogenic signals, and monocytes/macrophages being major target of HCV[12-14].

In 2002, it was noted that in males 25-54 years of age the incidence rates of NHL for blacks exceeded whites. This was also true for black females aged 25-34 years. The authors propose this increase in incidence is due to the prevalence of HIV in the African American community[3]. The high prevalence of HCV in the African American may also have contributed to the increased of NHL that was noted.

There was no evidence of acute exacerbation of HCV in our patient as his ALT remained less than 40 IU/L throughout the decompensation of his liver function. We also doubt that the patient was truly cirrhotic as his platelet count had been normal one month before, and his ultrasound and CT scan were not suggestive of cirrhosis. In the series by Zafrani et al[11], the clinical features of patients with ALF secondary to lymphoma/leukemia were characterized by average age of 49 years, hyperbilirubinemia, elevated liver transaminases, high LDH, and lactic acidosis. The majority had thrombocytopenia and prolonged prothrombin time. Our patient had all of these features. The observed disproportionate elevation in the AST compared to the ALT in our patient is similar to other reports. An AST/ALT ratio greater than 2 is characteristically seen in alcoholic liver disease and Wilson’s disease. A further conundrum in deciphering the diagnosis initially was the minimal elevation of ALP which argues against malignant infiltration as a consideration. Although the reason for this is unclear, ALP elevation had the lowest frequency of liver enzyme abnormalities in other series of ALF due to lymphoreticular malignancy[9,10]. Extreme elevations of LDH and lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia have been associated with ALF[15].

ACLF patients manifest in various forms due to the heterogeneity of this patient population. Severe jaundice, coagulopathy, multi-organ failure with encephalopathy and renal dysfunction, and systemic inflammatory response syndrome are common findings. Proinflammatory cytokines, neutrophil dysfunction and sepsis are believed to play a major role in pathogenesis and prognosis. Elevated leukocyte counts and C-reactive protein have been found to be common as well as evidence of occult or overt infection in ACLF patients. Dysregulated inflammation is considered a critical hallmark and final common pathway of the various insults of ACLF[16,17]. At the time of presentation our patient however, had normal white blood cell count and no evidence of infection. Further research will help define this subgroup of patients.

Several mechanisms by which NHL may cause ALF have been postulated: (1) massive hepatic sinusoidal infiltration by malignant cells could result in ischemia and hepatocyte necrosis; (2) tumor obstructing hepatic venules may also result in ischemic injury and necrosis; (3) intrahepatic bile ducts may also be infiltrated by lymphoma cells resulting in duct necrosis, cholangitis, and ALF; and (4) Rapid replacement of hepatic parenchyma by lymphomatous cells may lead to mass destruction of hepatocytes and resulting ACLF[11,18,19].

ACLF as the presenting feature of DLBCL is uncommon and, therefore, not typically considered in the differential diagnosis of liver failure. However, given the increasing incidence of DLBCL in older black men and patients with HCV and HIV/AIDS the diagnosis should especially be considered in this demographic group. Early diagnosis and referral requires a high index of suspicion as delayed diagnosis is usually fatal.

A 71-year-old African American man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection presented to the emergency room with lethargy and confusion.

The patient was jaundiced, somnolent, disoriented to place, and had non tender cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy.

Altered mental status secondary to hypoglycemia, drug overdose, sepsis, or hepatic encephalopathy was considered and adenopathy was biopsied to rule out infection or malignancy.

White count was normal with new anemia (hemoglobin = 9.6 g/dL), thrombocytopenia (platelet count = 96000/mL), hypoglycemia (blood glucose = 46 mg/dL), elevated lactate (4.1 mmol/L), cholestatic liver injury (direct bilirubin = 8.9 mg/dL, alkaline phosphatase = 221 IU/L, AST = 135 IU/L, ALT normal), and coagulopathy (INR = 1.6).

Abdominal CT scan showed a confluent circumaortic mass, multiple para-aortic and pelvic lymph nodes.

Lymph node biopsy revealed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in the clinical setting of acute liver failure.

Before transfer to another institution for chemotherapy, care was supportive with correction of hypoglycemia, lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy, oxygen, and empiric antibiotics.

Palta reported a case of acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) in a patient who had acute on chronic HBV and coexistent Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) refers to a constellation of disorders with heterogeneous clinico-pathologic features distinguished by a diffuse effacement of architecture composed mainly of large B-cells in different stages of maturation.

In cases of ACLF in patients with HCV and HIV, DLBCL should be considered in the differential diagnosis as the virus is lymphotropic as well as hepatotropic and early diagnosis and treatment may improve outcome.

The authors should discuss about possibility that HCV infection of B cells might have caused lymphoma and ACLF.

P- Reviewer: Endo I, Matsumori A S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wang CH

| 1. | Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55:965-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 330] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 2. | Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, Hartge P, Weisenburger DD, Linet MS. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood. 2006;107:265-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1230] [Cited by in RCA: 1218] [Article Influence: 64.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Clarke CA, Glaser SL. Changing incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. Cancer. 2002;94:2015-2023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bajaj JS. Defining acute-on-chronic liver failure: will East and West ever meet? Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1337-1339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jalan R, Gines P, Olson JC, Mookerjee RP, Moreau R, Garcia-Tsao G, Arroyo V, Kamath PS. Acute-on chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2012;57:1336-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 447] [Cited by in RCA: 457] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Olson JC, Kamath PS. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: what are the implications? Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2012;14:63-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Palta R, McClune A, Esrason K. Hodgkin’s lymphoma coexisting with liver failure secondary to acute on chronic hepatitis B. World J Clin Cases. 2013;1:37-40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Piris MA. I. Pathological and clinical diversity in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Hematol Oncol. 2013;31 Suppl 1:23-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood. 2011;117:5019-5032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1268] [Cited by in RCA: 1446] [Article Influence: 103.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lettieri CJ, Berg BW. Clinical features of non-Hodgkins lymphoma presenting with acute liver failure: a report of five cases and review of published experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1641-1646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zafrani ES, Leclercq B, Vernant JP, Pinaudeau Y, Chomette G, Dhumeaux D. Massive blastic infiltration of the liver: a cause of fulminant hepatic failure. Hepatology. 1983;3:428-432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Matsumori A. Leukocytes are the major target of hepatitis C virus infection: Possible mechanism of multiorgan involvement including the heart. CVD Prev Control. 2010;5:51-58. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Forghieri F, Luppi M, Barozzi P, Maffei R, Potenza L, Narni F, Marasca R. Pathogenetic mechanisms of hepatitis C virus-induced B-cell lymphomagenesis. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:807351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Peveling-Oberhag J, Arcaini L, Hansmann ML, Zeuzem S. Hepatitis C-associated B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas. Epidemiology, molecular signature and clinical management. J Hepatol. 2013;59:169-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Padilla GF, Garibay MA, Hummel HN, Avila R, Méndez A, Ramírez R. [Fulminant non-Hodgkin lymphoma presenting as lactic acidosis and acute liver failure: case report and literature review]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2009;39:129-134. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Sarin SK, Kumar A, Almeida JA, Chawla YK, Fan ST, Garg H, de Silva HJ, Hamid SS, Jalan R, Komolmit P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the study of the liver (APASL). Hepatol Int. 2009;3:269-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 643] [Article Influence: 40.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Olson JC, Kamath PS. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: concept, natural history, and prognosis. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Myszor MF, Record CO. Primary and secondary malignant disease of the liver and fulminant hepatic failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1990;12:441-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rowbotham D, Wendon J, Williams R. Acute liver failure secondary to hepatic infiltration: a single centre experience of 18 cases. Gut. 1998;42:576-580. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |